Estimation of Health-Care Costs for

Work-Related Injuries in the Mexican

Institute of Social Security

Fernando Carlos-Rivera,MScE,1Guadalupe Aguilar-Madrid,MD,Dr PH,2 Pablo Anaya Go´mez-Montenegro,MHA,1Cuauhte´moc A. Jua´rez-Pe´rez, MD,MSc,2

Francisco Rau´l Sa´nchez-Roma´n,MD,MSc,2

Jaqueline E.A. Durcudoy Montandon,MSc,2and Vı´ctor Hugo Borja-Aburto,MD,PhD2

Background Data on the economic consequences of occupational injuries is scarce in developing countries which prevents the recognition of their economic and social consequences. This study assess the direct heath care costs of work-related accidents in the Mexican Institute of Social Security, the largest health care institution in Latin America, which covered 12,735,856 workers and their families in 2005.

Methods We estimated the cost of treatment for 295,594 officially reported occupational injuries nation wide. A group of medical experts devised treatment algorithms to quantify resource utilization for occupational injuries to which unit costs were applied. Total costs were estimated as the product of the cost per illness and the severity weighted incidence of occupational accidents.

Results Occupational injury rate was 2.9 per 100 workers. Average medical care cost per case was $2,059 USD. The total cost of the health care of officially recognized injured workers was $753,420,222 USD. If injury rate is corrected for underreporting, the cost for formal injured workers is 791,216,460. If the same costs are applied for informal workers, approximately half of the working population in Mexico, the cost of healthcare for occupational injuries is about 1% of the gross domestic product.

Conclusions Health care costs of occupational accidents are similar to the economic direct expenditures to compensate death and disability in the social security system in Mexico. However, indirect costs might be as important as direct costs.Am. J. Ind. Med. 52:195–201, 2009.ß2008 Wiley-Liss, Inc.

KEY WORDS: costs; occupational accidents; IMSS; Mexico

INTRODUCTION

International indirect estimates have reported that work-related diseases and accidents represent a public health problem in most developing countries [Leigh et al., 1999; Giuffrida et al., 2002; Concha-Barrientos et al., 2005]. However, the lack of reliable and systematized data on work-related accidents and illnesses make it difficult to show the significant economic and social consequences of this problem in Latin American and other developing countries. For many countries official incidence data of occupational

2008 Wiley-Liss, Inc. 1RAC Salud Consultores, Mexico City, Mexico 2

Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social, Unidad de Investigacio¤n en Salud en el Trabajo, Mexico City, Mexico

Contract grant sponsors:Fondo de Fomento a la Investigacio¤n; Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social; Contract grant number:2005/2/I/353.

*Correspondence to:V|¤ctor Hugo Borja-Aburto, Coordinacio¤n de Salud en el Trabajo, Centro Me¤dico Nacional Siglo XXI, Av. Cuauhte¤moc 330, Edif. C, 1er piso, Col. Doctores, 06725 Me¤xico, D.F., Me¤xico. E-mail:victor.borja@imss.gob.mx

Accepted 28 October 2008

injuries show rates below developed countries, what erro-neously indicate that this is not a problem in those countries. This lack of information diminishes the priority of occupa-tional health and so begins a vicious circle. Work and health authorities, as well as business operators do not make decisions, and workers and the general public do not demand improvements in working conditions to reduce risks and prevent those accidents and illnesses [Nuwayhid, 2004]. The present study is an effort to estimate direct heath-care costs for occupational accidents in Mexico, as an example of the experience in developing countries.

Workers’ compensation plans in Mexico, called occupa-tional risks insurance, are mandatory for all workers in the formal sector of the economy. Occupational risks insurance provides health care for the worker in the case of his/her incurring some accident or disease associated with the exercise of his/her work, or an in-transit accident that may occur to and from the worker’s home and workplace. Similarly, the employer is covered with respect to short-and long-term economic obligations (subsidies, aid, global indemnizations, and pensions) that are established by the Mexican Federal Work Law [Ley Federal del Trabajo, 2002]. The Mexican Institute Social Security (IMSS) Law establishes that occupational risks insurance provisions should be fully covered by employer insurance quota payments. The formula for this premium recognizes and rewards those who invest in prevention, and sets greater financial contributions for companies registering higher insurance claims. Therefore, accurate data are required to classify enterprises and estimate the financial burden. Although this insurance contemplates an important health-care expenses component for workers experiencing occupa-tional accidents or diseases, actuarial valuations have basically taken into account the expenditure for indemnifi-cation for work-related disabilities and deaths, because IMSS accounting systems do not separate health-care cost by insurance branch. The balance for 2005 was an apparent net surplus of approximately one-third of 1.8 billion USD quota paid by employers [IMSS Report to the Federal Executive Branch and the Congress, 2005–2006]. The present study is an effort to estimate direct heath-care costs for occupational accidents and diseases for IMSS insured workers, as an example of the experience in developing countries.

METHODS

In order to quantify health-care costs, we carried out a study from the perspective of the health-services provider (IMSS) in which the variable of interest comprises direct medical costs for the year 2005. To determine health-care costs, it was necessary, on the one hand, to obtain the number and cases of work-related injuries, and on the other hand, to estimate their health-care costs.

Incidence of Occupational Injuries

The incidence of work-related injuries and illnesses in the year 2005 was obtained from the Occupational Health Information System [IMSS, Statistical Memory, [Memoria Estadı´stica], 2005]. This registry includes all injuries recognized as work-related accidents by occupational physicians, after they receive health care at IMSS owned and operated hospitals and clinics. Total temporary disability is paid at 100% of the salary since the first day of the accident until return to work, 1 year maximum, or a pension for permanent disability is granted. Previous reports have shown that 30% of occupational accidents are not registered [Salinas-Tovar et al., 2004]. Since occupational diseases are not as easily recognized as accidents are, only a few of them are declared and included in the registry. The incidence of occupational diseases (about 5,000 cases per year, basically traditional diseases: hearing loss and pneumoconiosis) obtained from these official reports was so low that this problem deserves special attention. Therefore, we decided not to include occupational illnesses in this report because this would underestimate the care cost of these diseases.

Occupational injuries were coded according to the World Health Organization’s International Disease Classi-fication Version 10 (WHO-IDC-10, 1995) and listed accord-ing to their frequency. We organized injuries into similar injury-type diagnostic groups (contusions, wounds, luxa-tions, fractures, etc.) and anatomic region groups (head, neck, thoracic organ, pelvic organ, etc.) according to the frequency of the event in the worker population. This way, we constituted 27 different injury groups that included 79% of the cases reported in the occupational health statistics. The remaining 21% of the cases were grouped as ‘‘other diagnoses.’’ For the total cost estimation, ‘‘other diagnoses’’ were assigned the average cost of diagnostic groups.

Care Cost Estimation

Medical costs included the following headings: out-patient specialty consultations (OSC); laboratory and imag-ing studies; drugs; surgery (SURG); rehabilitation; use of ambulances; primary care-level consultations, and occupa-tional health consultations (OHC).

To determine medical resources for each diagnostic group, the panels of experts defined the usual treatment algorithms at IMSS and later, resources employed. These panels of experts comprised 82 IMSS physicians in the Valley of Mexico, where they cared for20% of injured workers.

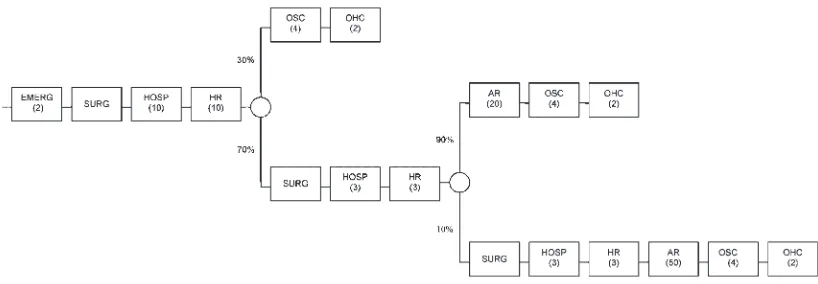

In the first study stage algorithms described typical treatment for each diagnosis according to its level of complexity or severity (e.g., see Fig. 1). For a single identical general diagnosis, various scenarios can be presented according to resources utilization necessary for medical care according to the severity and complications of his/her illness, that is, required the use of other services such as surgical interventions (SURG), in addition to hospitalization days (HOSP) and a greater number of ambulatory rehabilitation (AR) sessions, in comparison with patients not requiring surgery.

In the second stage of the study and from the treatment algorithms, we constructed databases with this information, and unit costs were divided by cost centers, by heading, and by event. In the case of headings, we included the following cost centers: consultations; hospital bed days; imaging examinations; laboratory examinations; surgical interven-tion, and minor procedures carried out in the consultory, while we classified the following by event: emergencies (EMERG); consultations; hospitalizations (HOSP); surgery (SURG); and intensive care unit (ICU). In addition to these, there are the following cost centers that comprise part of the two previous centers: rehabilitation, drugs, and OHC.

In the third study stage, we estimated costs taking as reference medical resources utilization for the treatment of each diagnosis, differentiating this according to the level of complexity. Likewise, the panels of specialists defined the

proportion of cases in each diagnostic group according to the complexity of each illness to be used to weight cases within each diagnostic group. Once the amount of each medical resource utilized in the care of the patient in each scenario was determined, these amounts were multiplied by unit costs, and a total cost weighted by the complexity of each patient in the diagnostic groups was obtained.

The formula employed for calculating the per-patient total cost was

Cjx¼

Xn

x¼1 QjxiPi

where Cjxis the cost for patient ‘‘j’’ with complexity ‘‘x,’’ Qjxi the amount utilized for medical resource care ‘‘i’’ used by patient ‘‘j’’ with complexity ‘‘x,’’ and Pi the unit cost of medical service ‘‘i.’’

In a fourth stage, the cost of each diagnosis was multiplied by the number of incident cases, and the sum of all these cases represents the total health-care cost of occupational accidents in the year 2005 at IMSS.

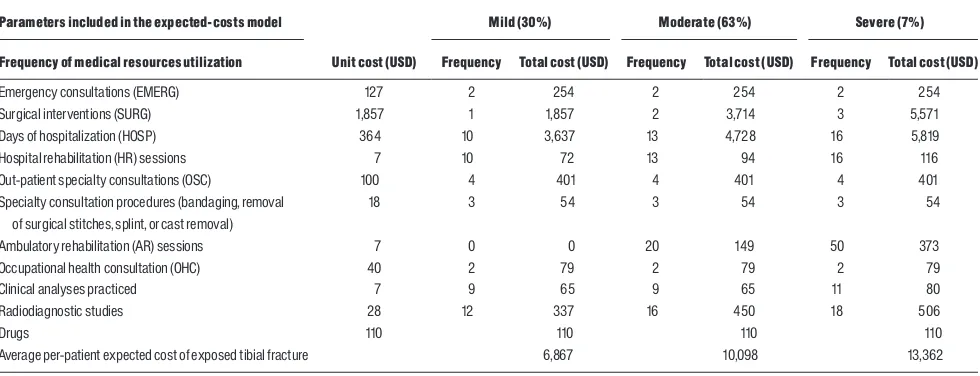

To broad the explanation of the methods, we included an example of an exposed tibial fracture. Figure 1 displays the treatment algorithm defined by the experts to identify the frequency of services utilization in the medical-care process from the patient’s admittance to the emergency room to his/ her hospital discharge and getting back to work after an occupation health physician certification. According to the panel of experts, there are three main types of tibial fracture, based on the number of surgeries per patient: mild, moderate, and severe (for one, two, and three procedures, respectively). Table I shows the total cost and the patient proportional distribution according to severity for tibial fractures. The expected costs for mild, moderate, and severe exposed tibial fractures were $6,867 USD, $10,098 USD, and $13,362 USD, respectively. Finally, the total cost for each fracture type is weighted by the frequency mentioned by the experts (30% mild, 63% moderate, and 7% severe); this result

FIGURE 1. Treatment algorithm of exposed tibia fracture. Mexican Institute of Social Security (IMSS), 2005. EMERG, Emergency

is applied to the expected per-patient calculated cost for an exposed tibial fracture, which in this case was $9,357 USD (Table II). Likewise, in this table we present the distribution by severity and the expected costs for two other different conditions.

RESULTS

In the year 2005, IMSS insured 12,735,856 workers (30% of the working population) against occupational injuries from 802,107 companies; of these workers, 373,239 received medical care for occupational risks (2.9/100 workers). Of these latter workers, 79% were classified as occupational accidents, 19% as commuting accidents, and the remaining 2% as occupational diseases. Of these occupational injuries, 1,367 were fatal and 13,450 generated permanent disabilities. In addition, occupational accidents caused a loss of 7,868,180 workdays due to temporary disability. The economic provisions to compensate for temporary loss of the ability to work and

indemnification for work-related permanent disabilities and deaths raised 578 million USD [IMSS, Statistical Memory, EOIT, 2005].

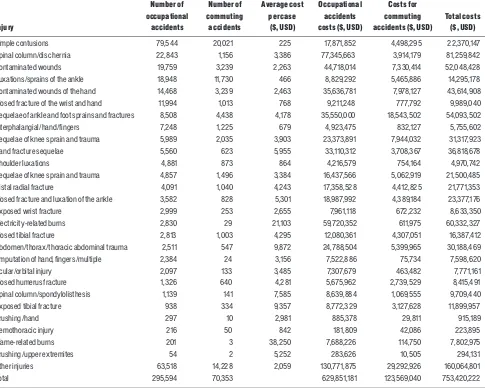

Table III shows health-care total costs for occupational accidents, separated from commuting or in-transit accidents, by 29 diagnostic groups incidence. Average medical cost of occupational accidents was $2,059 USD per case, with important variations ranging from $225 USD for simple contusions to $38,250 for flame-related burns treatment.

Simple contusions were the most frequent injuries— 79,544 cases per annum—but exhibited the lowest cost. Occupational accidents caused 2,384 hand and or finger amputations, with $3,156 USD per-case cost. Likewise, ocular injuries are similar in cost and incidence, but cause more disability. Finally, the highest average cost is represented by flame-related burns, with an average per-case cost of $38,250 USD and an incidence of 201 workers per year. The three most expensive cost centers for occupa-tional injuries were surgery, which comprised the 37.3% of the total costs, followed by hospital stay and by OSC with 30.1% and 12.0% of the total costs, respectively.

TABLE II. Examples of Estimation of Expected Costs for Different Conditions

Conditions

Mild Moderate Severe Expected costa

% Cost per case % Cost per case % Cost per case $ USD

Simple contusion 100 225 225

Spinal column/disc hernia 50 723 50 6,049 3,386 Exposed tibial fracture 30 6,867 63 10,098 7 13,362 9,357

a

The expect cost was calculated as the summatory of the products of the proportion of patients in each severity condition and their associated cost.

TABLE I. Cost Estimation of Exposed Tibial Fracture, Mexican Institute of Social Security (IMSS), 2005

Parameters included in the expected-costs model

Patient type according to resources utilization frequency

Unit cost (USD)

Mild (30%) Moderate (63%) Severe (7%)

Frequency of medical resources utilization Frequency Total cost (USD) Frequency Total cost (USD) Frequency Total cost (USD)

Emergency consultations (EMERG) 127 2 254 2 254 2 254

Surgical interventions (SURG) 1,857 1 1,857 2 3,714 3 5,571

Days of hospitalization (HOSP) 364 10 3,637 13 4,728 16 5,819

Hospital rehabilitation (HR) sessions 7 10 72 13 94 16 116

Out-patient specialty consultations (OSC) 100 4 401 4 401 4 401

Specialty consultation procedures (bandaging, removal of surgical stitches, splint, or cast removal)

18 3 54 3 54 3 54

Ambulatory rehabilitation (AR) sessions 7 0 0 20 149 50 373

Occupational health consultation (OHC) 40 2 79 2 79 2 79

Clinical analyses practiced 7 9 65 9 65 11 80

Radiodiagnostic studies 28 12 337 16 450 18 506

Drugs 110 110 110 110

Average per-patient expected cost of exposed tibial fracture 6,867 10,098 13,362

DISCUSSION

This study estimated the magnitude of the direct cost of health care of occupational injuries at IMSS. However, before we generalize the results nationwide, we must recognize some limitations derived from the use of official records to estimate incidence and the employed methodology for cost calculation.

Since consultation-derived medical files did not provide sufficient information for estimating treatment algorithms, we resorted to the opinion of a panel of experts composed of IMSS medical specialists. However, participating physicians from the Valley of Mexico, with whom we constructed treatment algorithms for each disease, might not accurately represent the treatment algorithms provided by physicians

and the actual treatment received by patients nationwide. However, it is worth to notice that most practicing physicians at IMSS are formed in the same institution and follow standards set by central authorities. Drugs and equipments are bought based on central guidelines, and physicians are not allowed to prescribe drugs out of a pre-established list. This could reduce uncertainties but does not completely eliminate possible bias on treatment estimates.

Another limitation is that occupational diseases were not included in these estimates. The reporting system for occupational diseases is particularly weak because of the difficulty to relate the cause of the disease to the working environment. Therefore, the misattribution of occupational illness to other sources can be more important than occupa-tional accidents. However, the contribution of occupaoccupa-tional

TABLE III.Total Costs of Occupational Accidents Ordered by Incidence, Mexican Institute of Social Security (IMSS), 2005

Injury

Number of occupational

accidents

Number of commuting

accidents

Average cost per case

($, USD)

Occupational accidents costs ($, USD)

Costs for commuting accidents ($, USD)

Total costs ($, USD)

Simple contusions 79,544 20,021 225 17,871,852 4,498,295 22,370,147 Spinal column/disc hernia 22,843 1,156 3,386 77,345,663 3,914,179 81,259,842 Contaminated wounds 19,759 3,239 2,263 44,718,014 7,330,414 52,048,428 Luxations/sprains of the ankle 18,948 11,730 466 8,829,292 5,465,886 14,295,178 Contaminated wounds of the hand 14,468 3,239 2,463 35,636,781 7,978,127 43,614,908 Closed fracture of the wrist and hand 11,994 1,013 768 9,211,248 777,792 9,989,040 Sequelae of ankle and foot sprains and fractures 8,508 4,438 4,178 35,550,000 18,543,502 54,093,502 Interphalangial/hand/fingers 7,248 1,225 679 4,923,475 832,127 5,755,602 Sequelae of knee sprain and trauma 5,989 2,035 3,903 23,373,891 7,944,032 31,317,923 Hand fracture sequelae 5,560 623 5,955 33,110,312 3,708,367 36,818,678 Shoulder luxations 4,881 873 864 4,216,579 754,164 4,970,742 Sequelae of knee sprain and trauma 4,857 1,496 3,384 16,437,566 5,062,919 21,500,485 Distal radial fracture 4,091 1,040 4,243 17,358,528 4,412,825 21,771,353 Closed fracture and luxation of the ankle 3,582 828 5,301 18,987,992 4,389,184 23,377,176 Exposed wrist fracture 2,999 253 2,655 7,961,118 672,232 8,633,350 Electricity-related burns 2,830 29 21,103 59,720,352 611,975 60,332,327 Closed tibial fracture 2,813 1,003 4,295 12,080,361 4,307,051 16,387,412 Abdomen/thorax/thoracic abdominal trauma 2,511 547 9,872 24,788,504 5,399,965 30,188,469 Amputation of hand, fingers/multiple 2,384 24 3,156 7,522,886 75,734 7,598,620 Ocular/orbital injury 2,097 133 3,485 7,307,679 463,482 7,771,161 Closed humerus fracture 1,326 640 4,281 5,675,962 2,739,529 8,415,491 Spinal column/spondylolisthesis 1,139 141 7,585 8,639,884 1,069,555 9,709,440 Exposed tibial fracture 938 334 9,357 8,772,329 3,127,628 11,899,957 Crushing/hand 297 10 2,981 885,378 29,811 915,189 Hemothoracic injury 216 50 842 181,809 42,086 223,895 Flame-related burns 201 3 38,250 7,688,226 114,750 7,802,975 Crushing/upper extremites 54 2 5,252 283,626 10,505 294,131 Other injuries 63,518 14,228 2,059 130,771,875 29,292,926 160,064,801 Total 295,594 70,353 629,851,181 123,569,040 753,420,222

illnesses to the total medical cost can be very high [Leigh et al., 2003].

The medical-care costs presented in this work are conservative estimates if compared with those carried out in other countries. This underestimation can originate from the low incidence of recognized occupational accidents and diseases at IMSS and due to lower unit costs of care in Mexico. The work-related injuries rate for 2005 was 2.9 per 100 workers, a number lower than that reported in U.S. and Canada and about half of that reported in Chile and Spain [International Labour Organization [ILO], Statistics, 2003 and 2007].

The injury-type classification process must take great care to avoid cross-over subsidies between branches where it is difficult to separate expenditures since health care is provided to their beneficiaries in various insurance branches, such as occupational injuries, common disease and maternity, volun-tary insurance, and health care for retired worker. If we correct for the 30% misclassification found in a recent report [Salinas-Tovar et al., 2004], the number of work-related injures would be 384,272 cases. Taking into account the average cost per case calculations of the present study, the corrected cost would be $ 791,216,460 USD.

It is noteworthy that the costs of injuries reported herein cannot be employed directly for estimating the costs of injuries occurring outside the work environment. The group of medical experts participating in the advisory panels who defined the proportion of patients according to the severity of each diagnostic group referred that in general terms, occupational injuries are considered as injuries with a greater risk of infection; thus, they should be managed more carefully. Nonetheless, on the other hand, workers are relatively healthier than the general population, and special management was not considered, for example, adult patients with co-morbidities such as diabetes and high blood pressure submitted to surgery.

The average cost of work-related injuries reported here is about half of the median health care of cost of 4,377 reported in a Canadian cohort [Alamgir et al., 2008].

This estimation demonstrates the high cost of health care for work-related injuries and the need to include them in any income–expense balance in a social security system, especially if financial incentives for prevention programs are considered. Cost appraisal data for commuting accidents are important for consideration, given that these are not included in occupational risk insurance-premium calculations. The cost of these commuting accidents represents 16% of the total cost.

The estimated health-care expenditures of occupational injuries at IMSS for 753 million USD and the costs for economic provisions to compensate for loss of the ability to work for 578 million USD for indemnification for work-related disabilities and deaths comprise only two components of the total occupational-injury costs. Indirect

costs might be as important as or more important than direct costs [Weil, 2001]. Indirect costs include loss of productivity, pain, and suffering-associated, as well as out-of-pocket expenses contracted by the family concerning patient home care. Conservative estimates suggest an indirect-to-direct cost ratio of 1:1 [Dorman, 1999]. There are many variations of the proportion of the costs but usually the proportion of indirect costs is much bigger than direct costs [Ha¨ma¨la¨inen et al., 2006; Brown et al., 2007].

At IMSS direct health-care costs of occupational accidents are completely covered by the premium paid by the employer. However, indirect costs are not directly compensated for by the social security system, but borne by workers, their families, employers, the public health system, and taxpayers. The fact that employers and social security institutions bear only a portion of total costs has implications in the appreciation of its true magnitude, the economic and social impact that occupational accidents and diseases represent for health-care institutions, the society, and the country.

IMSS covers most of the formal sector of the economy. However, the informal sector has grown rapidly during the last decades so that above figures solely reflect the reality of occupational accidents in 30% of the workers [Sa´nchez-Roma´n et al., 2006]. If we apply the rates of the population covered by IMSS to the total workforce, assuming similar occupational risks, we can estimate that 1.4 million work-related injuries occur each year in the country. The health-care expenditure under this occupational accidents and diseases is borne by the workers, public health system, and finally, the taxpayers. If similar direct cost could be applied, then health care and indemnification for work-related disabilities and deaths would be close to 1% of the NGP. This figure is similar to that reported in Costa Rica in 1995 by the National Insurance Institute (Instituto Nacional de Seguros), which exclusively administers occupational risks and covers 56% of the country’s work force (EAP) and 84.3% of the salaried population.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We gratefully thank the team of specialist who developed the treatment algorithms and the staff from the participating hospitals: Hospitales de Traumatologı´a y Ortopedia Victorio de la Fuente, Lomas Verdes, Pestalozzi, and Unidad de Medicina Familiar No. 1 from the Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social.

REFERENCES

Alamgir H, Tampa E, Koehoorn M, Ostra A, Demers P. 2008. Costs and compensation of work-related injuries in British Columbia sawmills. Occup Environ Med 64:196–201.

Brown J, Shanonn HS, Mustard CA, McDonough P. 2007. Social consequences of workplace injury: A population based study of workers in British Columbia, Canada. Am J Ind Med 50:633–645.

Concha-Barrientos M, Nelson DI, Fingerhut M, Driscoll T, Leigh J. The global burden due to occupational injury. 2005. Am J Ind Med 48:470– 481.

Cost Approximation of Work Claims in Spain, 2002. The costs of industrial accidents. Available Online: http://www.eurofound.europa. eu/eiro/2004/03/feature/es0403211f.htm

Diario Oficial de la Federacio´n. 2004. Costos unitarios de atencio´n Me´dica. Diario Oficial de la Federacio´n, 09 de marzo del 2004 y actualizacio´n al 2005, por la Coordinacio´n de Presupuesto e Informacio´n Programa´tica del IMSS.

Dorman P. 1999. Cost internalization in occupational safety and health: Prospects and limitations. Res Human Capital Develop 12:99–121.

Estadı´sticas de la Organizacio´n Internacional del Trabajo (OIT). 2003. Dan˜os ocupacionales: Agrupa accidentes y enfermedades de trabajo no fatales. Web site: http://laborsta.ilo.org/cgi-bin/brokerv8. exe.

European Agency for Safety and Health at Work. Inventory of socioeconomic costs of work accidents. 2002. Topic Centre on Research —Work and Health: Jos Mossink TNO Work and Employ-ment, the Netherlands, in cooperation with: Marc de Greef, Prevent, Belgium. Web site: http://osha.europa.eu/publications/reports/207/?set_ language¼es.

Giuffrida A, Fiunes R, Savedoff WD. 2002. Occupational risks in Latin America and the Caribbean: Economic and health dimensions. Health Policy Planning 17:235–246.

Ha¨ma¨la¨inen P, Takala J, Saarela KL. 2006. Global estimates of occupational accidents. Safety Sci 44:137–156.

Informe al Ejecutivo Federal y al Congreso de la Unio´n sobre la situacio´n financiera y los riesgos del Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social, 2005–2006. Web site: http://www.imss.gob.mx/NR/rdonlyres/ EB3485E7-83D6-431C-A355-F712700CBD38/0/Capı´tulo_V.pdf.

International Labour Organization (ILO). 2003. Statistics. Available at: http://laborsta.ilo.org/cgi-bin/brokerv8.exe.

International Labour Organization [ILO], Statistics. 2003 and 2007. Oficina Regional para America Latina y el Caribe. Available at: http:// laborsta.ilo.org/cgi-bin/brokerv8.exe#219.

Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social. 2005. Memoria estadı´stica. Coordinacio´n de Salud en el Trabajo. Divisio´n de prevencio´n de riesgos

de trabajo y a´rea de promocio´n de los trabajadores. Me´xico, D.F.: Divisio´n Te´cnica de Informacio´n en Estadı´stica en Salud. ST-5; 2006.

Leigh JP, Markowitz SB, Fahs M, Shin CH, Landrigan PJ. 1997. Occupational injury and illness in the United States; Estimates of costs, morbidity, and mortality. Arch Intern Med 157:1557–1568.

Leigh J, Macaskill P, Kuosma E, Mandryk J. 1999. Global burden of disease and injury due to occupational factors. Epidemiology 10:626– 631.

Leigh J, Yasmeer S, Millar T. 2003. Medical costs of fourteen occupational illnesses in the United States in 1999. Scand J Work Environ Health 29:304–313.

Ley Federal del Trabajo (LFT). 2002. Artı´culos 477 y 480, del Seguro de Riesgos de Trabajo, Tı´tulo noveno, Me´xico: Delma, 113p.

Ley del Seguro Social. 1995. Publicada en el Diario Oficial de la Federacio´n el 21 de diciembre de 1995. Incluye reformas y adiciones por decretos publicados en el Diario Oficial de la Federacio´n el 21 de noviembre de 1996 y el 20 de diciembre de 2001.

Nuwayhid IA. 2004. Occupational health research in developing countries: A partner for social justice. Am J Public Health 94:1916– 1921.

Organizacio´n Panamericana de la Salud. OPS , Organizacio´n Mundial de la Salud, 1998; Informe del proyecto de sistematizacio´n de datos ba´sicos sobre la salud de los trabajadores en paı´ses de las Ame´ricas: Barbados, Brasil, Colombia, Costa Rica, Chile, Jamaica, Me´xico, Panama´, Peru´, Venezuela. Varillas W, Eijkemans G, Tennassee M, Emmett E. OPS. web site: http://www.who.int/occupational_health/ regions/en/oehamrodato.pdf

Organizacio´n Panamericana de la Salud. OPS, Organizacio´n Mundial de la Salud. OMS 1999, 124.a Sesio´n del Comite´ Ejecutivo Salud de los Trabajadores en la Regio´n de las Ame´ricas. web site: http:// www.paho.org/spanish/gov/ce/ce124_18.pdf

Organizacio´n Panamericana de la Salud. OPS, Organizacio´n Mundial de la Salud. OMS. Plan Regional de Salud de los Trabajadores. 2001. Washington, D.C., USA: web site: http://www.who.int/occupational_ health/regions/en/oehamplanreg.pdf

Plan Regional de Salud de los Trabajadores. 2001. Washington, D.C., USA: Organizacio´n Panamericana de la Salud. web site: http:// www.who.int/occupational_health/regions/en/oehamplanreg.pdf.

Portal de Transparencia del IMSS. 2005. Web site: http:// transparencia.imss.gob.mx/html/imss%20va%20a%20comprar%20 imss%20compro.htm.

Salinas-Tovar JS, Lo´pez-Rojas P, Soto-Navarro MO, Caudillo-Araujo DE, Sa´nchez-Roma´n FR, Borja-Aburto VH. 2004. El subregistro potencial de los accidentes de trabajo en el Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social. Salud Pu´blica Mex 46:204–209.

Sa´nchez-Roma´n FR, Jua´rez-Pe´rez CA, Aguilar-Madrid G, Haro-Garcı´a LC, Borja-Aburto VH. 2006. Occupational health in Mexico. Int J Occup Environ Health 12:346–354.

Secretarı´a Confederal de Medio Ambiente y Salud Laboral. 2002. Aproximacio´n a los costes de la siniestralidad laboral en Espan˜a. Available at: http://www.fe.ccoo.es/sallab/Informe%20costes%20si-niestralidad%202004%20(1).pdf.

Weil D. 2001. Valuing the economic consequences of work injury and illness: A comparison of methods and findings. Am J Ind Med 40:418– 437.