2007; 29: 54–57

Addressing the hidden curriculum:

Understanding educator professionalism

ANITA DUHL GLICKEN & GERALD B. MERENSTEIN

University of Colorado at Denver and Health Sciences Center, Aurora, USA

Abstract

Several authors agree that student observations of behaviors are a far greater influence than prescriptions for behavior offered in the classroom. While these authors stress the importance of modeling of professional relationships with patients and colleagues, at times they have fallen short of acknowledging the importance of the values inherent in the role of the professional educator. This includes relationships and concomitant behaviors that stem from the responsibilities of being an educator based on expectations of institutional and societal culture. While medical professionals share standards of medical practice in exercising medical knowledge, few have obtained formal training in the knowledge, skills and attitudes requisite for teaching excellence. Attention needs to be paid to the professionalization of medical educators as teachers, a professionalization process that parallels and often intersects the values and behaviors of medical practice but remains a distinct and important body of knowledge and skills unto itself. Enhancing educator professionalism is a critical issue in educational reform, increasing accountability for meeting student needs. Assumptions regarding educator professionalism are subject to personal and cultural interpretation, warranting additional dialogue and research as we work to expand definitions and guidelines that assess and reward educator performance.

Over the past five years, several articles and reports have attempted to identify attributes and themes of medical professionalism (National Board of Medical Examiners 2003; Lynch et al. 2004; Surdyk et al. 2004). These papers document historical attempts to identify strategies to teach and assess these characteristics in medical professionals and students. Many of the commonly accepted attributes of professionalism remain consistent with those identified by Abraham Flexner (1915) in the early twentieth century in his descriptions of characteristics of the medical professional. In a recent special report from the Association of American Medical Colleges, Inui (2003) cites several taxonomies of domains summarizing common characteristics associated with professionalism. Lists include characteristics of altruism, honor and integrity; caring and compassion; respect; responsibility; accountability; excel-lence and scholarship; and leadership. Inui notes that these attributes are jointly endorsed by the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM), the American College of Physicians and the European Federation of Internal Medicine. Accreditation bodies also incorporate these characteristics into their expectations for program curricula. The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (1999) includes professionalism as one of six general competences required to be taught and assessed in all residence programs and the Association of American Medical Colleges’ Medical School Objectives Project (1998) highlights altruism and dutifulness as associated areas that should be taught in all medical schools. Similarly, the General Medical Council of the

UK (2006), the Canadian Medical Association (Kondro 2002) and the CanMeds 2000 Project of the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada (2005) all mandate professionalism as a priority in medical education and professional practice.

Many of these endorsements are based on the notion that physicians ‘develop’ or reform their concept of professionalism over the course of their education and that various attributes can be taught, modeled and institutionalized. In a recent publication Charlotte Rees (2005) describes a model of proto-professionalism, which assumes that professional develop-ment is influenced by nurture, is active and is staged. Those supporting this developmental view support a curriculum that teaches elements of professionalism across the spectrum of medical education. They note, however, that past research indicates that often students who come to medical education possessing desirable attributes leave with a very different profile:

As they move through their undergraduate medical education experience, our students also move from being open-minded to being fact-surfeited, from being intellectually curious to being increasingly focused on just that set of knowledge and skills that must be acquired to pass examinations, from being open-hearted and empathetic to being emotionally well-defended, from idealistic to cynical about medicine, medical practice, and the life of medicine. (Inui 2003, p. 19)

Correspondence:Anita Duhl Glicken, MSW, University of Colorado Health Sciences Center, Mail Stop F543, Aurora, CO 80045-0508, USA. Tel: 303-724-1338; fax: 303-724-1350; email: [email protected]

54 ISSN 0142–159X print/ISSN 1466–187X online/07/010054–4ß2007 Informa UK Ltd. DOI: 10.1080/01421590601182602

Med Teach Downloaded from informahealthcare.com by Technische Universiteit Eindhoven on 11/23/14

Previous research on transmission of professional values offers some explanation for this shift. A study by Stern (1998) found that a primary reason why medical students are not learning professional norms is that educators are not consistently teaching the values of the profession. This was supported in a study by Burack and colleagues (1999), who observed responses to unprofessional behavior in medical teams and documented that attending physicians were reluc-tant to respond to ‘perceived disrespect, uncaring or hostility towards patients’. Rather, they avoided or rationalized these behaviors, failing to address underlying attitudes and values.

We would argue that much of the decline in student adherence to ideal values, however, is not a result of lapses in formal curriculum. Most schools now have a course in medical professionalism and ethics (Makaul 1998) and also offer extensive programming in patient–provider communication. An alternative explanation lies in what has been termed ‘the hidden curriculum’. Several authors would agree that it is the students’ exposure to what they observe in day-to-day work with patients and one another that is a far greater influence than the prescriptions for behavior that are offered in the classroom. These authors argue that it is the modeling that students witness that has the most powerful effect on their professional development (Mathews, 2000; Kenny et al. 2003; Wright & Carrese, 2003). While these authors stress the modeling of professional relationships with patients and

colleagues, at times they have fallen short of acknowledging the importance of the values inherent in the role of the professional educator. This would include relationships and concomitant behaviors that stem from the responsibilities of being an educator based on the expectations of institutional and societal culture.

We first identified evidence of these lapses in behavior in our 1990 article entitled ‘Medical student abuse: Incidence, severity, and significance’ (Silver & Glicken 1990). In this report on the student population of one major medical school, 46.4% of all respondents stated that they had been abused at some time while enrolled in medical school, with 80.6% of seniors reporting being abused by the senior year. More than two-thirds (69.1%) of those abused reported that at least one of the episodes they experienced was of ‘major importance and very upsetting’. Half (49.6%) of the students indicated that the most serious episode of abuse affected them adversely for a month or more; 16.2% said that it would ‘always affect them’. We concluded that medical student abuse was perceived by these students to be a significant cause of stress and should be a major concern of those involved with medical student education. This study was followed by the publication of numerous other articles attesting to student perceptions of mistreatment during their medical training. It is important to note that the incidents of mistreatment identified by students should not be confused with dissatisfaction due to long work hours or on-call schedules. These incidents often consisted of observations of or experiences with unethical behavior, and experiences of harassment or discrimination (Dougherty et al. 1998). One student related the following: ‘I was examining another student in an ophthalmology practicum who turned out to have a corneal abrasion from previous tonometry. As my classmate was in obvious pain, I wanted to stop the examination. When I explained this to the supervising physician he said, ‘‘Oh good, this gives us an opportunity to learn how to force patient to cooperate even if they are in pain’’.’ A recent article by Wilkinson et al. (2006) further documents the serious impact of common adverse events during medical training.

These experiences are not easily catalogued into the taxonomies used in educating students for practice; however, recent efforts, like those of the University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine and the Association for Surgical Education (2005) have sought to identify professional behaviors from residents’ and students’ perspectives using elements of professionalism and behaviors defined by the ABIM, AAMC and ACGME to frame resident feedback on faculty professional behaviors. Although there is clearly overlap between the learning that prepares one to function as a medical profes-sional and the teaching that occurs in medical institutions, the dual role of the medical educator as both a medical professional and an educational professional requires that we look more closely at the educational literature for additional insight into factors that impact on the ‘hidden curriculum’.

This brings us back to the critical point of why this issue of educator professionalism is so important. A 1992 study by the United States Department of Education noted that educator professionalism is a critical issue in education reform. This is

Practice points

. Current literature continues to document faculty mis-treatment of students during medical training impacting on student attitudes and behaviors.

. While medical professionals share standards of medical practice in exercising medical knowledge, few have obtained formal training in the knowledge, skills and attitudes requisite for teaching excellence. These standards of educator professionalism are rarely framed in regard to teacher educators in medical training programs.

. Educator professionalism overlaps but is distinct from medical professionalism. Attention needs to be paid to the professionalization of medical educators as teachers, a professionalization process that parallels and often intersects with the values and behaviors of medical practice but remains a distinct and important body of knowledge and skills unto itself.

. Enhancing educator professionalism is a critical issue in educational reform, increasing accountability for meet-ing student needs. This is based on the underlymeet-ing theory that strengthening the educator professional will prove an effective means for meeting students’ needs and improving the overall quality of education.

. Assumptions about educator professionalism are subject to varied interpretation through a personal and cultural lens, warranting additional dialogue and research as we move forward to expand definitions and guidelines that assess and reward the performance of medical educators.

Educator professionalism

55

Med Teach Downloaded from informahealthcare.com by Technische Universiteit Eindhoven on 11/23/14

based on the underlying theory that strengthening the profession will prove an effective means for meeting students’ needs and improving the overall quality of education. In this way, educator professionalism promises to increase account-ability for meeting student needs. Historically, the primary focus of the professionalization movement in education has been discussed in terms of primary and secondary teachers. Rarely are these standards of professionalism framed with regard to teacher educators in colleges or medical school programs. However, the professionalism of all educators is an important goal. Unlike the primary or secondary educator, the medical teacher often comes with no preparation or training in education.

Many notions of professionalism applied to the medical practitioner are shared by the medical educator. Common beliefs and behaviors associated with the notion of profes-sionalism in education include that members of a profession share a common body of knowledge and use shared standards of practice in exercising their knowledge on behalf of clients. In addition, professionals strive for practice improvement and seek enhanced accountability. Professionals create methods to assure that practitioners will be committed and competent. ‘Professionals undergo rigorous preparation and socialization so that the public can have high levels of confidence that professionals will behave in knowledgeable and ethical ways.’

While medical professionals share standards of medical practice in exercising medical knowledge, few have obtained formal training in the knowledge, skills and attitudes requisite for teaching excellence. Policies of promotion and tenure offer some measure of accountability; however, many institutions reward research and scholarship, while overlooking the merits or deficits in teaching practice. Few would argue that rigorous preparation and socialization as an educator is lacking for most instructors. An argument can be made, therefore, that attention needs to be paid to the professionalization of medical educators as teachers, a professionalization process that parallels and often intersects the values and behaviors of medical practice but remains a distinct and important body of knowledge and skills unto itself.

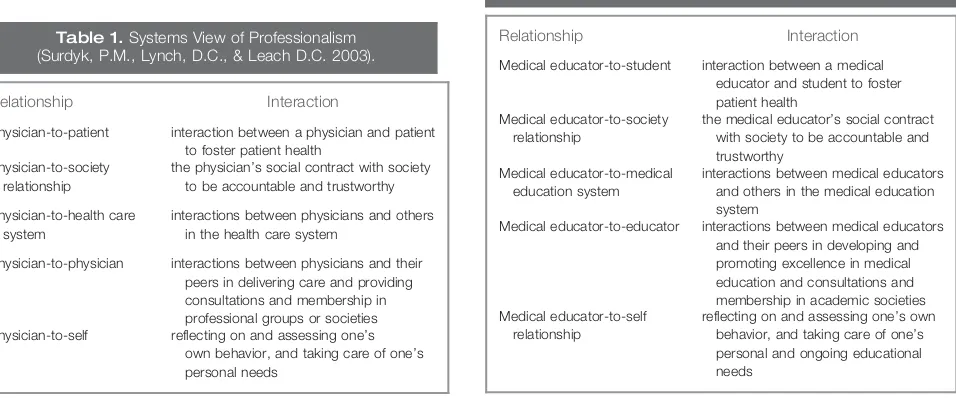

As noted repeatedly in the literature, the concept of professionalism is multidimensional and complex. The high level of complexity becomes more apparent, however, as we briefly explore how these two similar but different bodies of knowledge, skills and values are similar and different. In their review of current themes in the literature on medical professionalism from mid-2002 to 2003, Surdyk and colleagues (2004) describe the meaning of professionalism in terms of five types of overlapping relationships, which together support a systems view of professionalism (Table 1). It could be argued that these five types of overlapping relationships can be modified and applied to the medical educator–student and societal relationships.

At a recent workshop (Faculty Professionalism: The Other Part of the Hidden Curriculum—AMEE 2005) participants worked in small groups to identify attributes of student and medical faculty professionalism. While there was considerable overlap between these categories and across cultures in areas such as academic honesty, respect and self-awareness in practice, other attributes were described only in reference to faculty. These included qualities such as enthusiasm for their work, ‘pure’ caring about students, willingness to admit mistakes and be human, accountability to students, educa-tional institutions and society, and a commitment to lifelong learning and ongoing improvement of clinical and educational expertise. These attributes support an adaptation of the model proposed by Surdyk as depicted in Table 2.

The 25 workshop participants represented 16 countries of diverse cultural and ethnic background. Although there was general agreement on desirable attributes and qualities of the medical educator, the workshop also highlighted the complex-ity of this issue. For example, a case discussion involving a medical professor who is observed by a dean and community member to be having a drink with his students before clinic was, at face value, considered acceptable in some cultures and unacceptable in others. Similarly, a faculty member disciplin-ing a student in front of others for what some considered to be disrespectful behavior in front of a patient was also variably reviewed, some feeling this was culturally appropriate and,

Table 1.Systems View of Professionalism (Surdyk, P.M., Lynch, D.C., & Leach D.C. 2003).

Relationship Interaction

Physician-to-patient interaction between a physician and patient to foster patient health

Physician-to-society relationship

the physician’s social contract with society to be accountable and trustworthy

Physician-to-health care system

interactions between physicians and others in the health care system

Physician-to-physician interactions between physicians and their peers in delivering care and providing consultations and membership in professional groups or societies Physician-to-self reflecting on and assessing one’s

own behavior, and taking care of one’s personal needs

Table 2.Systems View of Medical Educator Professionalism.

Relationship Interaction

Medical educator-to-student interaction between a medical educator and student to foster patient health

Medical educator-to-society relationship

the medical educator’s social contract with society to be accountable and trustworthy

Medical educator-to-medical education system

interactions between medical educators and others in the medical education system

Medical educator-to-educator interactions between medical educators and their peers in developing and promoting excellence in medical education and consultations and membership in academic societies Medical educator-to-self

relationship

reflecting on and assessing one’s own behavior, and taking care of one’s personal and ongoing educational needs

A. D. Glicken & G. B. Merenstein

56

Med Teach Downloaded from informahealthcare.com by Technische Universiteit Eindhoven on 11/23/14

at times, desirable. This highlighted some of the challenges to promoting a shared philosophy of professionalism among colleagues. The group’s shared commitment to medical educator professionalism was subject to varied interpretation through a personal and cultural lens that warrants additional dialogue, particularly as we move forward to expand definitions and guidelines that assess and reward the performance of medical educators.

Parker Palmer in his book,The Courage to Teach (1998) describes a number of ordinary truths about teaching that are best expressed as paradoxes. Borrowing from these concepts, the paradox of the medical teacher can be expressed by the fact that the experience I have gained from 30 years in medical practice goes hand in hand with my sense of being a rank amateur in the skills of teaching at the start of every class I teach or new student I precept. Faculty often come to medical teaching with the wisdom and experience that dictates what their students need to know but are often ill-prepared to know how to communicate that information, skill or attitudinal set to their students. They often learn the ‘practice’ of educa-tion by trial and error from working with their students, who are often their best teachers. There is no easy fix to the complex problem of how to change a culture or how to quickly help faculty become professional educators. Professional behaviors in teaching and academic relationships, based on knowledge and values regarding educational roles and responsibilities, cannot change overnight. Students are close observers of what faculty do and how they behave in academic health centers but they also are active recipients of what faculty think, say and do in their interactions with students on a daily basis. The culture of the professional medical educator may need to be viewed simultaneously through a different lens—that of the professional educator— whereby we actively work to redefine what is meaningful and important in our work with our students.

Notes on contributors

ANITA DUHL GLICKEN, MSW, is Professor of Pediatrics, University of Colorado School of Medicine. She is President of the Physician Assistant Education Association and Director of the Child Health Associate Physician Assistant Program.

GERALD B. MERENSTEIN, MD, is Professor of Pediatrics, Medical Director of the Child Health Associate Physician Assistant Program and formerly Senior Associate Dean for Education at the University of Colorado School of Medicine.

References

Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. 1999. ACGME outcome project: general competencies. Retrieved 24 August 2006 from the World Wide Web:http://www.acge.org/outcome/comp/ compFull.asp

Association for Medical Education in Europe. Amsterdam 2005. Faculty professionalism: the other part of the hidden curriculum – pre-conference workshop, August 30, 2005.

Association of American Medical Colleges. 1998. Learning objectives for medical school education: guidelines for medical schools. Retrieved 24 August 2006 from the World Wide Web: http://aamc.org/meded/ msop

Burack JH, Irby DM, Carline JD, Root RK, Larson EB. 1999. Teaching compassion and respect: attending physicians’ responses to problem-atic behaviors. J Gen Intern Med 14:49–55.

Darling-Hammond L, Goodwin AL. 1993. Progress toward professionalism and teaching, in: G. Cawelti (Ed.)Challenges and Achievements of American Education: The 1993 ASCD Yearbook, pp. 19–52 (Alexandria, VA, Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development).

Daugherty S, Baldwin D, Rowley B. 1998. Learning, satisfaction, and mistreatment during medical internship a national survey of working conditions. J Amer Med Assoc 279:1194–1199.

Flexner A. 1915. Is Social Work a Profession? (New York, The New York School of Philanthropy, National Council on Charities and Corrections).

General Medical Council. 2006. Good medical practice. Retrieved 24 August 2006 from World Wide Web: http://www.gmc-Uk.org/ guidance/good_medical_practice_review/setting_standards_final_ march_06.pdf

Inui T. 2003. A Flag in the Wind: Educating for Professionalism in Medicine (Washington, DC, Association of American Medical Colleges).

Kenny NP, Mann KV, Macleod H. 2003. Role modeling in physicians’ professional formation: reconsidering an essential but untapped educational strategy. Acad Med 78:1203–1210.

Kondro W. 2002. Threats to medical professionalism tackled in Canada. Lancet 360:316.

Lynch D, Surdyk P, Eiser A. 2004. Assessing professionalism: a review of the literature. Med Teach 26:366–373.

Makoul G, Curry RH. 1998. Medical school courses in professional skills and perspectives. Acad Med 73:9–53.

Mann BD, Termuhlen PM, Ujiki M. The Resident, the Student, and the Competencies: A guide on how to use the competencies as criteria for evaluating faculty-resident-student interaction. Retrieved 24 August 2006 from the World Wide Web: http://www.facs.org/education/rap/ mann0106.html

Mathews C. 2000. Role modeling: how does it influence teaching in family medicine? Med Educ 34:443–448.

National Board of Medical Examiners. 2003. Embedding professionalism in medical education: assessment as a tool for implementation. Retrieved 24 August 2006 from the World Wide Web: http://www.nbme.org/ about/publications.asp

Palmer P. 1998.The Courage to Teach Exploring the Inner Landscape of a Teacher’s Life(San Francisco, Jossey-Bass).

Rees C. 2005. Proto-professionalism and the three questions about development. Med Educ 39:7–11.

Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada. 2005. The CanMEDS roles framework. Retrieved 24 August 2006 from the World Wide Web: http://rcpsc.medical.org/canmeds/index.php

Silver HK, Glicken AD. 1990. Medical student abuse. Incidence, severity, and significance. J Amer Med Assoc 263:527–532.

Stern DT. 1998. Practicing what we preach? An analysis of the curriculum of values in medical education. Am J Med 104:569–575.

Surdyk P, Lynch D, Leach D. 2003 Professionalism: identifying current themes. Cur Opin Anaesthesiol 16:597–602.

United States Department of Education. 1995. Systematic reform in the professionalism of educators. Retrieved 24 August 2006 from the World Wide Web: http://www.ed.gov/pubs/SER/ProfEd/bkgd.html Wilkinson TJ, Gill DJ, Fitzjohn J, Palmer CL, Mulder RT. The impact on

students of adverse experiences during medical school. Med Teach 28:129–135.

Wright SM, Carrese JA. 2003. Excellence in role modeling: insights and perspectives from the pros. Can Med Assoc J 167:638–643.

Educator professionalism

57

Med Teach Downloaded from informahealthcare.com by Technische Universiteit Eindhoven on 11/23/14