Unlocking the potential of induced grassroots

organizations as proponents of sustainable

forest management in Vietnam

1

Unlocking the potential of induced grassroots organizations as

proponents of sustainable forest management in Vietnam

By Tran Thi Binh, PhD1

Key messages:

Many organizations created with the aim of improving community forest management (CFM) in Vietnam are “Induced grassroots organizations” (IGOs)1 - organizations created through donor or government funding.

IGOs can play a critical role in promoting the voice of local resource users in forest

governance, but in order to do this they need to meet local communities’ livelihood

aspirations and provide meaningful opportunities for local participation.

Many IGOs decision-making becomes dominated by government interests when insufficient attention is paid to socially inclusive participatory processes and when the regulatory environment is insufficiently enabling to empower communities to make forest management decisions themselves.

Introduction

Over the past two decades, the Government of Vietnam (GoV) has experimented with a variety of policies seeking to include local people in sustainable forest management. For example, Decree 02/CP (dated January 1994) marked a radical move in shifting forest management responsibility away from state organizations to individual households. IGOs are

expected to encourage local people’s participation in forest management, which would make a significant contribution to sustainable forest management (see Box 1).

This brief, based on PhD research of three IGOs in Quang Tri province (see Map 1), explains how IGOs can make important contributions to sustainable forest management in Vietnam. It argues that IGOs can only play an important role if they are developed and sustained in a collaborative manner. This brief also demonstrates that today’s IGOs tend to be technocratic2 in nature, which severely restricts their contributions on the ground.

1

Binh Tran completed her PhD at School of Geography, Queen Mary University of London in March 2012.

The author would like to thank Dr Thomas Sikor at DEV, University of East Anglia, and Dr Nguyen Quang Tan and other reviewers at RECOFTC for their valuable comments for this policy brief. She also would like to express her gratitude to Queen Mary College Studentship without which her PhD this would not have been possible.

2

In the 1950s and 1960s, under the technocratic school of thought, it was thought that enhanced technical capacity of professionals in forest management would be much more important to guarantee better forest conditions. As a result,

ensuring people’s participation in decision-making was not given priority, and natural resources were often managed to protect their aesthetic beauty and biological values, not necessarily in the interests of people living around them (Woodcock, 2002). In this context, local people were regarded as culprits responsible for the destruction of natural resources. As a result, they were often bypassed if they were perceived as having inadequate capacity compared to that of the experts (Chambers, 1983; Bond and Hulme, 1999).

Box 1: Example IGOs

2 ethnic minority) and Kinh (the majority ethnic group in Vietnam) people. The second Indochina War which resulted in forest degradation, displacement of people and 45 to 75 poverty rates left the villages in a state of high vulnerability. After 1975, state institutions nationalized the forests, replacing traditional forest governance. State-owned forestry enterprises were established to control forest extraction and forestland clearance for arable land. Traditional forest management practices became obsolete, as the majority of inhabitants were migrants and a state decision-making structure replaced the traditional one. Yet, local people had little knowledge of the new system. According to them, “We don’t understand anything about the laws. In the past, we only knew about forest management rules established by the Già Làng (traditional village heads)”. In addition, villagers had little sense of responsibility when they did not feel they were the owner of the forest, “although recently we discussed the issues of deforestation and its effects on our life, we did not come up with solutions because we think that this is a task for government departments”.

In the early 2000s, two international donor funded projects sought to reverse the decline in awareness of environmental issues will increase along with opportunities for these groups to develop.

How IGOs turn into technocratic institutions

Despite the good intentions, in practice the IGOs did not facilitate broad-based local participation. All IGOs were set up by the relevant Commune People Committees (CPC) with varying level of control from the provincial (Village B) and district (Villages A and C) Forest Protection Department (FPD), so they consisted mainly of government staff.

A number of serious shortcomings hampered the IGOs in all three villages. First, the IGOs strengthened the capacity of local government, not

3 Following the guidance and approval for Consent for the Research by University of London’s Research Ethics Committee the study villages were coded A, B, C to ensure their anonymity.

3

the local communities, to manage forests. Failing to mobilise wider participation of villagers meant that these groups lost their general assemblies, rendering the existence of these groups to mere extensions of government organizations. Second, there was insufficient investment in IGOs for livelihood improvement. Material supply (i.e rattan seedlings) was available but limited. In one village, only 5 out of 54 households in the village gained access to this support. In all study villages, no extension services or market advice were provided to support livelihood activities.

Picture 1: IGO members drawing routes of their forest patrols

Third, other benefits from joining IGOs were minimal. One of major objectives of the IGOs is to support sustainable harvesting of both timber and non-timber products for subsistence use among the study villages as one of incentives to encourage people to join forest protection led by IGOs. Regarding firewood, the development of seasonal calendars with women in these villages revealed that women did not collect firewood from the forests their villages were assigned to protect. Meanwhile, timber for house construction turned out to be unattractive or unavailable. For many families, their priority was to secure enough food. For others, they could not sell timber to build brick houses, which they either preferred or found the timber unsatisfactory for home building.

Fourth, the IGOs became more concerned with forest protection and policing the local people than encouraging them to participate in beneficial IGO activities. The primary task undertaken by the IGOs was to go on forest patrol to stop illegal logging and monitor biodiversity. Villagers, in turn, understood the IGOs’ mission as seeking to “stop local people from clearing forests” and to “punish local people if they continue cutting trees.”

This technocratic orientation made the IGOs focus on the government’s goal of forest

protection and ignore local people’s needs and aspirations for livelihood improvements. As a

result, IGOs rarely took part in forest management planning or other decision-making processes. In village A, the IGO was unaware for more than a year of a plan to establish a nature reserve around the village even though the IGO had been set up for the purpose of biodiversity monitoring and forest protection. In that regard, the IGOs increased local

people’s vulnerability. They should have been providing them with new opportunities to “We did not know about the plan for the

4

participate in forest management and overcome the conflict between forest protection and livelihood improvement. It was not surprising that local villagers, “assented to government requests for participation in forest patrols or forest protection, but they took no action to implement their commitments”, as stated by an FDP staff.

A collaborative approach to IGOs

The insights from Quang Tri show that IGOs can contribute to sustainable forest management in Vietnam, but only if they are developed and sustained in a collaborative manner. Collaboration requires that IGOs, as representatives of local people, become equal partners with government agencies in the forest governance process. Local communities need support to be able to take part in participatory decision making and to organise themselves.

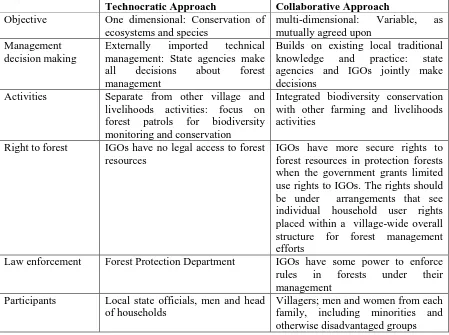

A collaborative approach for promoting the participation of IGOs in managing natural and protection forests should be guided by the set of principles set out in the Table 1.

Table 1: Comparison between technocratic and collaborative approaches for managing protection forests in Vietnam

Technocratic Approach Collaborative Approach

Objective One dimensional: Conservation of ecosystems and species management: State agencies make all decisions about forest management

Builds on existing local traditional knowledge and practice: state agencies and IGOs jointly make decisions

Activities Separate from other village and livelihoods activities: focus on forest patrols for biodiversity monitoring and conservation

Integrated biodiversity conservation with other farming and livelihoods activities

Right to forest IGOs have no legal access to forest resources

IGOs have more secure rights to forest resources in protection forests when the government grants limited use rights to IGOs. The rights should be under arrangements that see individual household user rights placed within a village-wide overall structure for forest management efforts

Law enforcement Forest Protection Department IGOs have some power to enforce rules in forests under their management

Participants Local state officials, men and head of households

Villagers; men and women from each family, including minorities and otherwise disadvantaged groups

5

Consent (FPIC4) process, which in turn might make PFES and REDD+ more responsive to locality.

Policy Implications

IGOs should not be established in a technocratic manner if they are expected to contribute to sustainable forest management or effective PFES or REDD+ implementation. Neither governments nor large international donors have done enough to promote fully participatory IGOs, as demonstrated by the experience reported above. Nevertheless, the GoV and international donors can do more to empower local communities and promote more participatory IGOs in a collaborative manner through the following measures:

Provide an enabling legal and administrative framework for the operation of IGOs. For example, enabling them to register under the 2007 Decree on Cooperative Groups, which enables them to receive more sufficient financial support from outside. Alternatively, allow (I)GOs to structure themselves as they decide in terms of executive and sub- committees so long as certain principles are upheld.

Allow the use of forest resources. One possible method is to divide and develop different user rights to IGOs within protection forests and protected areas under co-management agreements developed between co-management boards and IGOs.

Simplify the procedures for forest management planning and harvesting applicable to co-management agreements between government agencies and IGOs.

Mainstream support to IGOs in project design by integrating indicators for IGO performance in project monitoring and evaluation.

Strengthen the responsiveness of forest protection officers to IGO reports of illegal logging activities.

6

Further reading and references

Bond, R. and Hulme, D. 1999. Process Approaches to Development: Theory and Sri Lankan Practices World Development. 27(8). 1339-1358.

Borrini-Feyerabend, B. Taghi Farvar, M. Nguinguiri, J. and Ndangang, V. 2000. The Co-management of Natural Resources: Organizing, Negotiating and Learning-by-Doing (Access at http://www.eldis.org/static/DOC10516.htm).

Chambers, R. 1983. Rural Development: Putting the Last First. London: Longman.

Tran Thi Binh. 2012. Strengthening Grassroots Organizations for Forest Management: the Case of Induced Forest-based Grassroots Groups in Quang Tri Province, Vietnam. PhD Thesis submitted to Queen Mary, University of London.

Uphoff, N. 1982. Rural Development and Local Organizations in Asia. New Delhi: Macmillan India Ltd.

RECOFTC