Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 11 January 2016, At: 22:14

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

Lifelong Learning: Characteristics, Skills, and

Activities for a Business College Curriculum

Douglas Love

To cite this article: Douglas Love (2011) Lifelong Learning: Characteristics, Skills, and Activities for a Business College Curriculum, Journal of Education for Business, 86:3, 155-162, DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2010.492050

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832323.2010.492050

Published online: 24 Feb 2011.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 393

View related articles

CopyrightC Taylor & Francis Group, LLC ISSN: 0883-2323

DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2010.492050

Lifelong Learning: Characteristics, Skills, and

Activities for a Business College Curriculum

Douglas Love

Illinois State University, Normal, Illinois, USA

The literature places great importance on lifelong learning, but leaves its meaning open to a wide range of interpretations. Much is written about lifelong learning after leaving school with little about business college preparation of lifelong learners. This is the departure point for the study’s providing one college’s operational definition of lifelong learning by identifying 8 specific characteristics the faculty said lifelong learners should possess. The authors identify 18 skills the faculty believes lead to the achievement of the lifelong learner characteristics and describes activities that develop these skills. Other institutions may benefit by adapting the enumerated characteristics, skills, and activities as well as the process used to determine them.

Keywords: business education, lifelong learning, lifelong learning activities, portfolio, pro-fessionalism, self directed learning

“Learning is not compulsory . . . neither is survival” (W. Edwards Deming cited by Moyer, 2007, p. 148). “Lifelong learning . . . is a necessity rather than a possibility or a lux-ury to be considered”(Fischer, 1999, p. 21). Although the literature continues to places great importance on lifelong learning, it also continues to leave the meaning of the term open to a wide range of interpretations. Any institution want-ing its students to possess lifelong learnwant-ing skills must first define the term. Parkinson (1999) found hundreds of cita-tions about lifelong learning after leaving school, with few addressing how students can be prepared for lifelong learn-ing durlearn-ing secondary or postsecondary schoollearn-ing. This is the point of departure for the current study. This study pro-vides one college’s operational definition of lifelong learning by identifying eight specific characteristics the faculty said lifelong learners should possess. It identifies specific skills that the faculty believes lead to the achievement of the life-long learner characteristics and describes how development of these skills was integrated in the curriculum.

In the first section of the article I discuss the relevant lifelong learning literature in an effort to make sense of the term. In the next section I briefly describe the discovery and consensus building steps used to obtain broad faculty agree-ment about an operational definition of lifelong learning and the activities to help students master the competencies. After

Correspondence should be addressed to Douglas Love, Illinois State University, Department of Accounting and Business Information Systems, 5520, Normal, IL 61790-5520, USA. E-mail: [email protected]

describing these consensus building activities, the eight life-long learning competencies are presented. I then enumerate skills the faculty believes lead to the achievement of the life-long learner characteristics and show how development of these skills were interwoven into student activities piloted in the college curriculum. I discuss how other institutions might use these results in the final section.

WHAT IS LIFELONG LEARNING?

The earnestness of the lifelong literature is illustrated by the opening quotations and other authors’ descriptions of it as essential (Wu, 2008) and a necessity for survival (Hake, 1999; Jongbloed, 2002; Kasworm & Hemmingsen, 2007). However, the meaning of the term has many interpretations with their own lexicons (Schraeder, Freeman, & Durham, 2007; Smith, 2001).

Lifelong learning has been equated with continuing edu-cation (Bruce, 2006) and training (Dunn, 2000). The idea of it occurring in adulthood and spanning a life time is incor-porated in Schraeder et al. (2007) citing Fellers (1996), “The notion that a college graduate is a ‘finished good’ is being challenged and replaced with the notion of lifelong learning; education is a process that one continues throughout his or her career and lifetime” (p. 45). Some argue definitions of lifelong learning are changing in response to globalization and other forces (De Freitas and Jameson, 2006).

Marks (2002) noted possible meanings ranging from a “second chance access to higher education for adults wishing

156 D. LOVE

to learn to short-term skilling or re-skilling for those in un-stable careers and temporary jobs” (p. 1) as well as purposes ranging “from teaching of specific ‘competencies’ of which . . . employers can make use to learning ‘for its own sake’ and . . . value of learned individuals to the world at large” (p. 5). Page, Bevelander, Bond, and Boniuk (2006) observed that the lifelong literature related to business tends to focuses on the need for continuous training rather than “self-motivated learning through life” (p. 2).

Jarvis (1999) distinguished between lifelong learning and lifelong education, noting significant differences and voicing the concern that the former term’s embracement by govern-ments coming to be defined as work-life learning rather than lifelong learning.

Using tools that facilitate lifelong learning sometimes become part of its description. Certainly, information and communications technology has broken down barriers to lifelong learning (De Freitas & Jameson, 2006; Dykman & Davis, 2008). Although not formally defining lifelong learn-ing, Evans and Fan (2002) considered the use of Web-based technology for facilitating it noting that “lifelong learning has come to involve a variety of learning experiences or modes” (pp. 127–128).

Attempts have been made at all encompassing defini-tions, such as of the European Council, cited by Lewis and Whitlock (2002), “All learning activity undertaken through-out life, with the aim of improving knowledge, skills and competence, within a personal, civic, social and/or employ-ment related perspective” (p. 15). They question whether the proposed definition is even workable. Smith (2001) ques-tioned the term itself:

“Lifelong learning” is a general term seldom used in current educational research. Several more precise terms are used to better fit the conceptualization of education theorists and researchers...goals of these researchers are chiefly the same:

to learn about the attributes and skills of those who take control of their own learning, and the conditions that promote learning development. (p. 664)

This observation may appear to be fatal for those wanting to use the term to refer to an exit skill set graduates should possess, however, business colleges face similar curricular challenges on a regular basis. Globalization, diversity, and sustainability are other examples of general terms used to describe competencies that business colleges address. It is necessary for those within an institution to achieve consensus about the meaning that is presumably consistent with some use in the literature.

Lifelong learning is often coupled with students taking responsibility for their own learning (Taras, 2002). Dynan, Cate, and Rhee (2008, p. 96) argued that acquisition of self-directed learning skill (SDL) equips students to be lifelong learners and referred to Knowles (1975) to identify SDL as “a process in which individuals take the initiative . . . in

diagnosing their learning needs, formulating learning goals, identifying human and material resources, choosing . . . learn-ing strategies, and evaluatlearn-ing learnlearn-ing outcomes” (p. 18). Some of the lifelong learner characteristics identified here are similar to those identified by Dynan et al. (2008), but with the explicit recognition of professional organizations as an important source of human and material resources.

Lifelong learning also is viewed as part of being pro-fessional. Johnsson and Hager (2008) saw commitment to lifelong learning as an essential element of fitness for profes-sional practice. Garman, Evans, Krause, and Anfossi (2006) examined professionalism in the health care environment, citing the Healthcare Leadership Alliance’s definition of its professionalism competency that includes the phrase, “a commitment to lifelong learning.” Self managing is one of four components of professionalism, and its focus is partic-ipating in proactive career planning and lifelong learning. They indicated the best way to develop the competency is to start by gaining an understanding of one’s current levels of mastery. Assessment is identified as a significant factor (James & Too, 2005) contributing to lifelong learning with calls for greater student participation through self-assessment (Taras, 2002).

The following elements from the literature figure promi-nently in the characteristics, skills, and activities indentified in this study:

• Self-motivated learning throughout a lifetime; • Self-assessment;

• Planning, including formulation of goals and identifica-tion of learning resources;

• Professionalism and mastering competencies that are of value in the market place; and

• Learning for the value of learned individuals to the world at large.

Even though the initial faculty consensus building ac-tivities, by design, were carried out prior to consulting the literature, these elements found their way into the college’s proposed lifelong learning curriculum.

BUILDING CONSENSUS BEGINNING WITH THE MISSION STATEMENT

Initially, Illinois State University College of Business en-gaged in an extensive strategic planning process involving faculty chairs of the major college teams, department chairs, the dean, associate dean, and six additional faculty mem-bers. One outcome of this effort was this mission statement prominently featuring lifelong learning:

To be a highly respected college of business that develops professionals with the personal dedication, ethics and life-long learning capabilities needed to succeed professionally

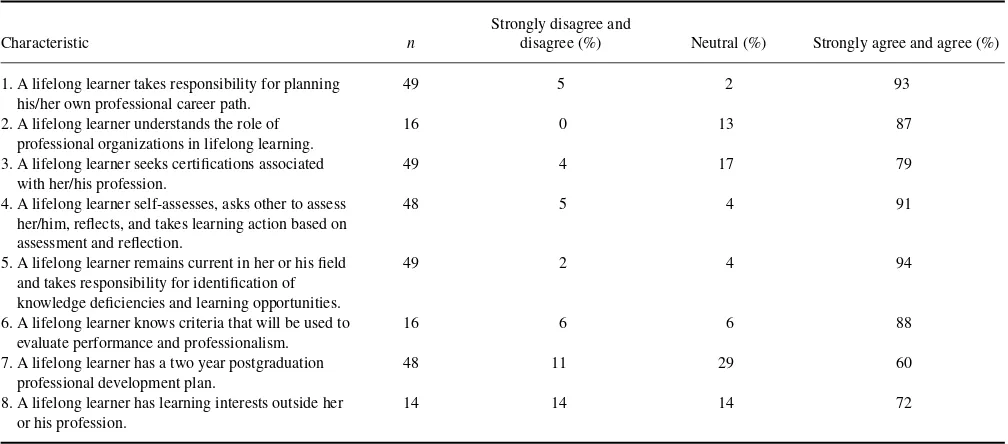

TABLE 1

Faculty Evaluation of Lifelong Learning Characteristics

Characteristic n

Strongly disagree and

disagree (%) Neutral (%) Strongly agree and agree (%)

1. A lifelong learner takes responsibility for planning his/her own professional career path.

49 5 2 93

2. A lifelong learner understands the role of professional organizations in lifelong learning.

16 0 13 87

3. A lifelong learner seeks certifications associated with her/his profession.

49 4 17 79

4. A lifelong learner self-assesses, asks other to assess her/him, reflects, and takes learning action based on assessment and reflection.

48 5 4 91

5. A lifelong learner remains current in her or his field and takes responsibility for identification of knowledge deficiencies and learning opportunities.

49 2 4 94

6. A lifelong learner knows criteria that will be used to evaluate performance and professionalism.

16 6 6 88

7. A lifelong learner has a two year postgraduation professional development plan.

48 11 29 60

8. A lifelong learner has learning interests outside her or his profession.

14 14 14 72

and to serve society. We work as a diverse community pro-moting excellence in learning, teaching, scholarship, and ser-vice.

These strategic planning activities and resulting docu-ments at least briefly focused the entire faculty’s attention on lifelong learning and gave responsibility for its detailed examination to the college’s curriculum team.

The prominence of lifelong learning in the college’s mis-sion and strategic planning documents not only demonstrated the college leadership’s support, it also reflected an initial step in building faculty consensus. The carefully crafted and widely supported mission statement combined with col-lege accrediting body’s (Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business) promise to hold member institutions accountable for fulfilling their missions were motivation for initiating a process to assure our curriculum was contributing to the development of student lifelong learning capabilities.

IDENTIFICATION OF LIFELONG LEARNING CHARACTERISTICS AND SKILLS

Having stated in the college’s mission that graduates would possess lifelong learning capabilities, the next step was to define what this meant in practice. As customary at the col-lege’s fall conference, faculty members, administrators, and advisors participated in breakout sessions to address issues associated with the strategic planning document. Three of the breakout groups were assigned a brainstorming activ-ity related to lifelong learning that called on members to individually compose lists of characteristics and skills they associated with lifelong learning capability and then use a

flip chart to record a group consensus list for reporting to all in attendance.

Notes and flip charts from the fall conference breakout session were given to a subgroup of the curriculum team for analysis and development. This subgroup produced a draft document that was reviewed by the entire curriculum team resulting in eight characteristics of a lifelong learner shown in the first column of Table 1. The curriculum team’s presentation of the characteristics of a lifelong learner to the general faculty was one of several agenda items for a spring faculty meeting where attendees were provided a document enumerating characteristics and describing skills of a lifelong learner along with example skill building activities. Thirty-two audience response devices, or clickers, were distributed to collect real-time feedback about the curriculum team’s propositions as each was presented.

The clicker format was novel and engaged the meet-ing participants in tightly focused discussions by immedi-ately presenting quantified responses. A written form was distributed to meeting attendees for whom clickers were not available. Combined survey results are summarized in Table 1. Due to meeting time constraints, two characteristics were not polled for clicker response, but were polled with the paper survey. This is the reason for the smaller sample sizes for items 2 and 6.

The results were overwhelmingly supportive of the char-acteristics used to define lifelong learning. For ease of in-terpreting the responses, the five response categories were collapsed into three. For all characteristics except the eighth, the responsesstrongly agreeingexceeded the number agree-ing. Although the results were still strongly supportive, the greatest reservation was for having a 2-year professional de-velopment plan upon graduation. Some believed focusing

158 D. LOVE

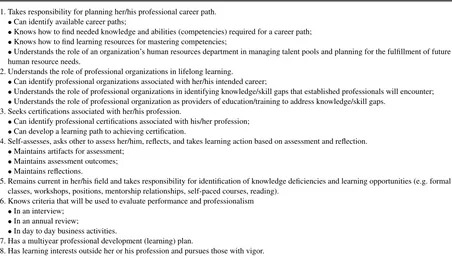

TABLE 2

Eight Characteristics and Associated Skills of a Lifelong Learner

1. Takes responsibility for planning her/his professional career path. •Can identify available career paths;

•Knows how to find needed knowledge and abilities (competencies) required for a career path; •Knows how to find learning resources for mastering competencies;

•Understands the role of an organization’s human resources department in managing talent pools and planning for the fulfillment of future human resource needs.

2. Understands the role of professional organizations in lifelong learning.

•Can identify professional organizations associated with her/his intended career;

•Understands the role of professional organizations in identifying knowledge/skill gaps that established professionals will encounter; •Understands the role of professional organization as providers of education/training to address knowledge/skill gaps.

3. Seeks certifications associated with her/his profession.

•Can identify professional certifications associated with his/her profession; •Can develop a learning path to achieving certification.

4. Self-assesses, asks other to assess her/him, reflects, and takes learning action based on assessment and reflection. •Maintains artifacts for assessment;

•Maintains assessment outcomes; •Maintains reflections.

5. Remains current in her/his field and takes responsibility for identification of knowledge deficiencies and learning opportunities (e.g. formal classes, workshops, positions, mentorship relationships, self-paced courses, reading).

6. Knows criteria that will be used to evaluate performance and professionalism •In an interview;

•In an annual review;

•In day to day business activities.

7. Has a multiyear professional development (learning) plan.

8. Has learning interests outside her or his profession and pursues those with vigor.

on job responsibilities should be the foremost priority for new hires. Other comments noted that certifications were not available in some disciplines, but that a lifelong learner could still self-assess against recognized needed knowledge and abilities to identify areas for improvement.

Another question, posed only to the clicker respondents (n =32), asked about the number of characteristics. A total of 60% of the clicker respondents indicated the number of char-acteristics was about right, 27% of the respondents indicated there were too many characteristics, and 13% indicated there were important characteristics that were missing. The overall show of strong support is surprising even though respondents participated in the flip chart brainstorming activity the prior semester.

Based on the faculty responses in the clicker survey, the ensuing discussion, and written feedback, the eight char-acteristics of a lifelong learner operationalized by specific measurable skills are shown in Table 2. The curriculum team’s analysis of faculty input for the first characteristic, lifelong learner takes responsibility for planning his/her own professional career path (characteristic 1), found the fac-ulty believed someone possessing the characteristic must be able to,

• Identify available career paths;

• Know how to find needed knowledge and abilities (com-petencies) required for a career path;

• Know how to find learning resources for mastering com-petencies; and

• Understand the role of a human resources department in managing talent pools and planning for the fulfillment of future human resource needs.

Taking responsibility for planning a career (characteristic 1) may seem obvious to seasoned professionals, but most new graduates just have left an academic setting in which advising center staff provided students with exact require-ments for graduation and detailed plans of study, and moni-tored progress toward graduation. Anecdotal input from the college’s industry advisory council members indicated that corporations are shifting career path management responsi-bilities from the employer to the employee. Page et al. (2006) noted,

Education institutions that focus more on developing self-motivated lifelong learners play a much greater role in con-tributing to the business world and to society in general. They produce individuals who develop themselves in an inter-organizational rather than an intra-inter-organizational way. Such individuals do not rely exclusively on the firm to develop them and, paradoxically, they thus become more valuable as lifetime employees. (p. 1)

The role of the professional organization and certification that is often under the auspices of the professional organiza-tions is prominent in two of the characteristics: The lifelong learner understands the role of the professional organiza-tions in lifelong learning (characteristic 2) and the lifelong learner seeks certification(s) associated with her or his pro-fession (characteristic 3). Accounting propro-fessionals certainly

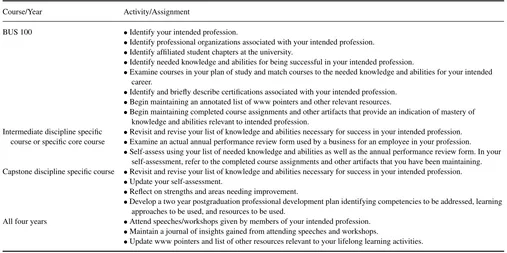

TABLE 3

Proposed Lifelong Learning Activities: Undergraduate COB Curriculum

Course/Year Activity/Assignment

BUS 100 •Identify your intended profession.

•Identify professional organizations associated with your intended profession. •Identify affiliated student chapters at the university.

•Identify needed knowledge and abilities for being successful in your intended profession.

•Examine courses in your plan of study and match courses to the needed knowledge and abilities for your intended career.

•Identify and briefly describe certifications associated with your intended profession. •Begin maintaining an annotated list of www pointers and other relevant resources.

•Begin maintaining completed course assignments and other artifacts that provide an indication of mastery of knowledge and abilities relevant to intended profession.

Intermediate discipline specific course or specific core course

•Revisit and revise your list of knowledge and abilities necessary for success in your intended profession. •Examine an actual annual performance review form used by a business for an employee in your profession. •Self-assess using your list of needed knowledge and abilities as well as the annual performance review form. In your

self-assessment, refer to the completed course assignments and other artifacts that you have been maintaining. Capstone discipline specific course •Revisit and revise your list of knowledge and abilities necessary for success in your intended profession.

•Update your self-assessment.

•Reflect on strengths and areas needing improvement.

•Develop a two year postgraduation professional development plan identifying competencies to be addressed, learning approaches to be used, and resources to be used.

All four years •Attend speeches/workshops given by members of your intended profession. •Maintain a journal of insights gained from attending speeches and workshops.

•Update www pointers and list of other resources relevant to your lifelong learning activities.

Note.New graduates of an undergraduate program will not have mastered all of the competencies required to be a lifelong learner. The undergraduate activities are proposed to provide a foundation for a College of Business Graduate to become a lifelong learner.

are familiar with the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA). Among this organization’s five objec-tives are certification and licensing along with standards and performance. The standards and performance objective is to establish professional standards; assist members in continu-ally improving their professional conduct, performance and expertise; and monitors such performance to enforce current standards and requirements (American Institute of Certified Public Accountants, 2009a).

Even after graduating and achieving professional certi-fication (characteristic 3), the lifelong learner self-assesses, asks other to assess her or him, reflects, and takes learning action based on assessment and reflection (characteristic 4). The lifelong learner knows criteria that will be used to evalu-ate performance and professionalism (characteristic 6). The AICPA’s recently published Core Competency Framework for Entry into the Accounting Profession which identifies and defines competencies needed for successfully entering the profession is an example (American Institute of Cer-tified Public Accountants, 2009b). In the information sys-tems (IS) discipline, there has been longstanding coopera-tion among various IS professional organizacoopera-tions to identify needed knowledge and abilities for working effectively in the discipline (Association for Information Systems, 2002).

Evaluation criteria related to competencies (characteristic 6) and action in response to assessment results (characteristic 4) along with other activities undertaken to remain present in the field (characteristic 5) are reflected in a multiyear

professional development (learning) plan (characteristic 7) maintained by the lifelong learner.

The lifelong learner has interest outside her or his pro-fession and pursues those with vigor (characteristic 8). To anticipate and understand changes within a profession, the lifelong learner must monitor and understand the broader en-vironment (e.g. social, political, technical) surrounding the profession.

Elements in Lifelong Learning Activities

Table 3 includes 18 elements to be incorporated in lifelong learning activities for the undergraduate business curriculum that are intended to develop the characteristics identified in Table 2. The two columns of the table show the targeted courses and the basic elements of the assignments. The ini-tial activities the student encounters build awareness of pro-fessional organizations and needed knowledge and abilities for various business professions. Next, the student discov-ers the relationships between the knowledge and abilities required for his or her profession and the development of these in the courses making up the student’s plan of study. These awareness activities are intended for the first semester the student is on campus. By early in their third year, stu-dents understand self-assessment and performance appraisal and are actively engaged in the former. Development of self-assessment skills sets the stage for the student to develop a 2-year postgraduation professional development plan.

160 D. LOVE

Some students who have piloted the professional develop-ment plan have referred to their plans when interviewing for jobs and have asked recruiters about professional develop-ment support that organizations offer. Some students that had already accepted job offers when the 2-year plan activity was undertaken developed their plans in consultation with their future employers.

At Illinois State University, BUS 100 is a 3-hr first-year level course required for all business majors that introduces students to the business enterprise and its functional areas and also engages students in career planning. Table 3 indi-cates that activities and assignments in this course help the student identify a profession and the organizations associ-ated with this profession, local as well as national. Students become aware of certifications associated with the selected profession and needed knowledge and abilities for success. They maintain an annotated list of Web resources and also maintain completed assignments in this course as well as other courses that demonstrate the level of mastery of the needed knowledge and abilities. Of course, these BUS 100 activities could be spread among other courses at schools not having a similar first-year course.

Activities in an intermediate course related to the stu-dent’s major call on the student to revisit the list of needed knowledge and abilities for working effectively in her or his intended profession and to do a self-assessment. This ac-tivity includes examination of an organization’s actual per-formance appraisal form for practitioners in the student’s intended profession.

The third set of activities is intended to be part of a discipline specific capstone course when the student is ap-proaching graduation and therefore near entry into her/his profession. They incorporate a reexamination of the needed knowledge and abilities for working in the profession along with a revision of the previous self-assessment, but also call on the student to develop a 2-year postgraduation profes-sional development plan. In a pilot of this activity at least one student that had accepted a job offer for future employ-ment worked with the employer to develop the plan. On the first day of employment the student had a 2-year professional development that already had the approval of the employer.

Example Assignments and Student Artifacts

The curriculum team inventoried lifelong learning skill build-ing assignments already in the college’s curriculum and found a series of short assignments given to BUS 100 students to be tightly aligned with the lifelong learning elements the team thought should be embodied in activities at that level. Students began this series by writing a two- to three-page “Who Am I” narrative as part of a Life Vision Portfolio. Next, each student read about the Myers-Briggs Type indi-cator and completed the questionnaire to identify her or his type. Building on these activities, each student composed a futuristic resume. This activity required the student to think

about an intended profession and the needed knowledge and abilities for that profession by having the student write the resume the student would like to possess 4 years hence. As a final activity, each student wrote a reflective narrative about his or her ideal first job after graduation (Bantham, 2006). The combination of activities incorporated many of the ele-ments in the BUS 100 entry of Table 3, but in a creative way that was more engaging than the item by item enumeration shown in the table.

The student’s next significant encounter with lifelong learning is a self-assessment assignment targeted for the be-ginning of the student’s junior year and can be placed in an existing core course required of all business students or in an existing intermediate discipline specific course for each major. The activity asks the student to review descriptions of needed knowledge and abilities compiled by professional organizations associated with the student’s intended occu-pation and then draw on example experiences from her or his course, cocurricular work, and other life experiences to document her or his level of mastery of the various needed knowledge and abilities. Students responded to this piloted activity by placing their multimedia work including text, images, sound, and links to web resources in a Web-based portfolio system.

One student’s exemplary response identified the specific professional organization related to her intended profession, but indicated after a several-hour Google search she found the career centers’ and marketing departments’ Web sites at several universities to be the most helpful in identifying key characteristics for her profession. She documented and linked to six of these sites and then constructed a table show-ing 12 skill groups gleaned from these sites that she felt were needed for success in her profession. She then provided ex-tensive evidence for her level of mastery of each including the following describing an internship experience:

This internship was largely based on my own effort, enthu-siasm, and independent thinking as I had minimal instruc-tion and supervision. I flourished in this environment . . . I developed/improved a lot of skills while performing my job functions: researching and identifying high net worth clients, developing a database to manage all of the information, cre-ating a marketing brochure for these prospects, as well as other financial and marketing projects. I actually made such an impression, that I would later serve as a marketing con-sultant from time to time . . . I was called on to “freelance” presentation materials, marketing materials, and more.

She provided more than a dozen additional descriptions fol-lowed by a section of reflective concluding thoughts along with links to numerous marketing organization and associ-ations; career planning sites; and job resource sites that she compiled. The Works Cited section for her multimedia com-position contained 50 entries.

The final significant lifelong learning development en-counter is intended for the student’s last year in an existing capstone course, either the capstone course for the student’s major or an existing capstone course required of all business students. The piloted capstone lifelong learning assignment consisted of four parts intended to not only enhance self-assessment skills, but also build on those skills to create a 2-year postgraduation professional development plan. For the first part of the assignment, the student revisited the list of needed knowledge and abilities compiled for the earlier lifelong learning exercises. For the second part, the student updated the self-assessment. To provide additional founda-tion for the student’s self-assessment, the student is given an actual annual employee performance evaluation form that the student completed with self-evaluation comments. The essence of the third and fourth parts of the piloted assign-ment were the following:

• Even though you may be less than a year from gradua-tion, it is unlikely that you will be excellent in all or even most of the areas shown in the table. Develop a plan for enhancing your skills during the first two years after grad-uation. Certainly most employers will provide training in some areas, but you are responsible for your professional development and your future will be determined by your own planning.

• Identify and link to Internet resources that assist in im-proving the skill level of the characteristics. Please be judicious in your choice of links and limit them to the highest quality sites.

A student’s response to a pilot of this demonstrated the as-signment could be strengthened by also requesting the stu-dent to istu-dentify an intended career path with a targeted em-ployer. The student already had accepted a job offer with a large international equipment manufacturing company when given the capstone assignment so he worked with his fu-ture supervisor to develop his plan. In his discussions, he discovered that his development plan would depend on the career path he wanted to follow within the organization, so he first developed a 4-year company career plan. In particu-lar, he identified a specific assignment he wanted to obtain following the customary time in his entry position with the company. His professional development plan targeted skills that would help him obtain that assignment. He also iden-tified three other professional enhancements, two involving knowledge about technology and the other about leadership.

HOW OTHER INSTITUTIONS MIGHT USE THESE RESULTS

Implementation of curricular change to enhance student mas-tery of lifelong learning skills faces two significant hurdles. The first is that the change may involve multiple

disci-plines and span administrative (e.g., department) boundaries. Clearly curricular change requiring faculty member involve-ment from multiple disciplines and administrative units can present special problems. Two activities designed to engage faculty and staff involvement at two points in the curricular development process were employed. By design, the entire college faculty is engaged in the initial brainstorming activity and then in a review activity with minimal claim on partici-pant time. Lifelong learning project champions emerge from the initial brainstorming activities with subsequent steps en-couraging their participation. This appears to be a low-cost approach to engaging not only champions but also those that otherwise might not participate.

A second hurdle is that faculty consensus about curric-ular changes may be difficult to achieve due to differences in faculty member definitions of lifelong learning and the competencies associated with mastering it. Because of the interdisciplinary nature of lifelong learning and the range of interpretations of the concept, it is unlikely that an institution would want to attempt to address lifelong leaning by simply implementing the pilot assignments presented here. Instead, it may be useful to tailor the process for building faculty consensus about lifelong learning to the institution. The in-stitution may find it useful to provide a brief summary of the lifelong learning literature and then poll its faculty and staff about the characteristics in Table 2 comparing results with those reported here. The skills and assignments presented here can then be examined.

REFERENCES

American Institute of Certified Public Accountants. (2009a). Mission. Retrieved from http://www.aicpa.org/About+the+AICPA/AICPA+ Mission

American Institute of Certified Public Accountants. (2009b). What is the framework? AICPA Core Competency Framework for Entry into the Accounting Profession. Retrieved from http://www.aicpa.org/edu/ overview.htm

Association for Information Systems. (2002). Participants. Informa-tion systems 2002. Retrieved http://192.245.222.212:8009/IS2002Doc/ Main Frame.htm

Bantham, J. (2006).BUS 100 enterprise assignments. Unpublished course assignments, Illinois State University, Normal, IL.

Bruce, R. (2006, September 7). Why learning goes on after the classroom continuing professional development Robert Bruce explains the thinking behind lifelong training and the benefits it brings: [SURVEYS EDITION].

Financial Times, 2.

De Freitas, S., & Jameson, J. (2006). Collaborative e-support for lifelong learning.British Journal of Educational Technology,37, 817–824. Dunn, K. (2000). Rutgers University creates culture of lifelong learning.

Workforce,79, 108–109.

Dykman, C., & Davis, C. (2008). Part one: The shift towards online educa-tion.Journal of Information Systems Education,19, 11–16.

Dynan, L., Cate, T., & Rhee, K. (2008). The impact of learning structure on students’ readiness for self-directed learning.Journal of Education for Business,84, 96–100.

Evans, C., & Fan, J. P. (2002). Lifelong learning through the virtual univer-sity.Campus-Wide Information Systems,19, 127–134.

162 D. LOVE

Fellers, J. W. (1996). Teaching teamwork: Exploring the use of cooperative learning teams in information systems.The DATA BASE for Advances in Information Systems,27(2), 40–60.

Fischer, G. (1999). Lifelong learning: Changing mindsets. In G. Cumming, T. Okamoto, & L. Gomez (Eds.),7th international conference on com-puters in education on new human abilities for the networked society(pp. 21–30). Omaha, NE: IOS Press.

Garman, A. N., Evans, R., Krause, M. K., & Anfossi, J. (2006). Profession-alism.Journal of Healthcare Management,51, 219–222.

Hake, B. (1999). Lifelong learning in late modernity: The challenges to so-cieties, organizations, and individuals.Adult Education Quarterly,49(2), 79–90.

James, J., & Too, M. C. (2005). An action research approach to de-veloping an information systems academic subject that facilitates lifelong learning. ACIS 2005 Proceedings. Paper 8. Retrieved from http://aisel.aisnet.org/acis2005/8

Jarvis, P. (1999). Global trends in lifelong learning and the response of the universities.Comparative Education,35, 249–257.

Johnsson, M. C., & Hager, P. (2008). Navigating the wilderness of becoming professional.Journal of Workplace Learning,20, 526–536.

Jongbloed, B. (2002). Lifelong learning: Implications for institutions.

Higher Education,44, 413–431.

Kasworm, C., & Hemmingsen, L. (2007). Preparing professionals for life-long learning: Comparative examination of master’s education programs.

Higher Education,54, 449–468.

Knowles, M. S. (1975).Self-directed learning: A guide for learners and teachers. New York, NY: Association Press.

Lewis, R., & Whitlock, Q. (2002). Learning: A corporate perspective. Train-ing Journal, May, 14–18.

Marks, A. (2002). A grown up university? Towards a manifesto for lifelong learning.Journal of Education Policy,17(1), 1–11.

Moyer, D. (2007, May). The stages of learning.Harvard Business Review,

85(5), 148.

Page, M. J., Bevelander, D., Bond, D., & Boniuk, E. (2006). Business schools and lifelong learning: Inquiry, delivery, or developing the inquiring mind.

South African Journal of Business Management,37(4), 1–5.

Parkinson, A. (1999, November).Developing the attribute of lifelong learn-ing. Paper presented at the 29th ASEE/IEEE Frontiers in Education Con-ference, San Juan, Puerto Rico.

Schraeder, M., Freeman, W., & Durham, C. (2007). A lexicon for lifelong learning.The Journal for Quality and Participation,30(4), 31–36. Smith, P. A. (2001). Understanding self-regulated learning and its

impli-cations for accounting educators and researchers.Issues in Accounting Education,16, 663–700.

Taras, M. (2002). Using assessment for learning and learning from as-sessment. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 27, 501– 510.

Wu, A. (2008). Integrating the AICPA core competencies into classroom teaching: A practitioner’s experiences in transitioning to academia.CPA Journal,78(8), 64–67.