Copyright c2013 by UniversityPublications.net

GENDER BIAS ON FOUCAULT’S CONCEPT OF PANOPTICON IN

UNDERSTANDING THE STRUCTURE OF

PESANTREN

(ISLAMIC

BOARDING SCHOOL) IN INDONESIA

Siti Kholifah

Brawijaya University, Indonesia

The main focus of this study is to examine the physical structures of pesantren (Islamic boarding school) and the rules that have been designed to maintain and control santri (students in pesantren) within and outside pesantren. This study also investigates the power and authority of the pesantren leader used both to perpetuate pesantren traditions and mediate the influences from outside pesantren. These are important issues because the pesantren is an educational institution within the Islamic community in Java that tends to preserve patriarchal values. Using Foucault’s Panopticon that based on Bentham’s concept and a feminist perspective through participant observation and qualitative interviews, this research was conducted in two Javanese pesantren: Mu’allimin and Mu’allimaat in Yogyakarta, and Nurul Huda in Malang. This research shows the structures in the pesantren rules have been developed to educate and internalise Islamic teaching and gender values to santri. These pesantren resemble Foucault’s panopticon, not only related to the pesantren physical structures, but also related to the rules in a pesantren which are designed to integrate class rules with those of the everyday lives of the santri. The integrated system in the pesantren explains how the leaders exercise their authority and the santri always obey. The panopticon system in the pesantren has a gender bias; the rules and complex system create more opportunity for male santri to access information and knowledge. This situation also creates gender awareness and critical thinking among the female santri.

Keywords: Pesantren, Panopticon, Gender.

Introduction

Pesantren1 is an educational institution with Islamic religion as a specific academic course, and still assumed by NGOs and Islamic activists to have a biased concept of gender. Patriarchal Islamic views of women were conveyed in written works by Moslem scholars that became educational material in

1

Pesantren is the oldest traditional Islamic educational boarding school, which has experienced transformation as a modern educational institution. Pesantren have been able to bridge the emergence of the new generation of educated Moslems who are familiar with modernisist terms. In its latest development, pesantren can be categorised as either ‘salaf pesantren’ that focus on texts on classical Islam (also known as the yellow texts), or ‘khalaf pesantren’ that offer education on modern Islam including general science. Viewed from ideological religious aspects, pesantren offer variety, although generally pesantren in Indonesia offer modern religious interpretation (Jabali & Subhan 2007:64-5).

pesantren. These works included Sheikh Nawawi al Batani’s, Uqud al-Lujjaynfi Bayan Huquq az-Zawjayn (Book of Marriage) (Muttaqin 2008:71). Pesantren have also been using kitab kuning (yellow texts)2 that contain gender biased interpretations of Islamic teaching.

During the early era of pesantren development in the sixteenth century, pesantren exclusively taught male santri dominated by priyayi (Javanese aristocratic elite) families (Ricklefs 2008:46, 357). In this period, only women from families with a high position had access to higher or modern education, and these women attended pengajian3(Srimulyani 2008:84). In the 1910s several pesantren opened separate facilities for girls (Dhofier 1999:17-8). The opportunity for women to study in Islamic boarding schools means that parents send their daughters to pesantren because they believe they are safe environments for educating their children (Doorn-Harder 2006:174). Even though females have access to education in Islamic boarding schools, the number of male students has increased (Azra, Afrianty & Hefner 2007:180).

However, a segregated system that separates women and men for religious teaching still applies at pesantren. This segregation not only happens in the classroom but also in the curriculum (Doorn-Harder 2006:182). Discrimination against women in education is still evident in the provision of teaching materials and teaching methods. For example, female students learn Arabic writing and/or pegon4 at pesantren unlike the male students, they do not study the Malay language, written in the Latin script and female students were taught by female teachers (Doorn-Harder 2006:174). According to Dhofier (1999:33) some daughters of kyai (man leader in pesantren) obtained advanced Islamic teaching texts including yellow texts from their father. Dorn Harder (2006:174) notes that when female students wanted to learn romanised Malay they had to borrow teaching material from their brothers. The access of females to information was still limited, because many newspapers and books were written in romanised Malay. Formal education in colonial times and the business of government was conducted in Malay written in Latin script, in addition to the Dutch language.

The pesantren system experienced great change during the twentieth century, with some pesantren expanding their curricula to include general subjects (mathematics, history, Dutch language) as well as religious studies (Dhofier 1999:18). According to Azra et al (2007:175) “the change was primarily a response to two developments: the Dutch colonial authorities’ introduction of general education for Indonesians and, in the first decades of the twentieth century, the spread of modern Islamic schools across Indonesia.” These conditions illustrate that pesantren have significant roles in the development of Indonesian society, and women also have roles in managing pesantren.

Furthermore, major reform of the education system in pesantren continued in the 1980s and 1990s focusing on teaching culture and teaching methods in pesantren (Barton 2002:162). The development of pesantren has rapidly grown5 as a form of coeducational education, especially in Java.6 Efforts to enhance the quality of the education system include opening up to perspectives on development from outside, using modern scientific methodologies and diversifying programs and activities in pesantren. However, O’Honlon (2006:40) has observed at several pesantren in East Java (Malang, Pasuruan and Lamongan)

2

Kitab kuning (yellow texts) are classical scholarly texts; for the most part they are commentaries on the Qur’an and Islamic law and written in Arabic.

3

Pengajian is informal groups for the study of Islamic teaching or yellow texts in once or twice a week. 4

Pegon is handwriting with Javanese/Madurese/Sundanese/ Indonesian language that is written in Arabic script Jawi.

5

According to the Department of Religious Affairs, in 2001 the number of students, who were studying at 11,312 pesantren, was about 2,737,805. In 2008 the number of pesantren was more than 21,521 (not all pesantren are registered with the Ministry of Religious Affairs), and the number of students was 3,818,469 (approx 20-25%children and adolescents fromthe total Indonesian student population) (Indonesia 2008a, 2008b).

6In 2008 the number of Java pesantren was 16,704 (77.62% of the total Indonesian pesantren) and the number of

that the rules for female santri are stricter than for male santri. Male students usually have more opportunities to obtain knowledge and information than female students. And a kyai has the authority and power to dominate the management of pesantren (Dhofier 1999:25). Moreover, the kyai is one of five pesantren elements7 that have political and social roles within the community, the region and at times within the nation (Wagiman 1997:105; Dhofier 1999:35; Endang 2005:82; Kholifah 2005:188-9; Karim 2008:157; Srimulyani 2008:81). As a result, the kyai is the most important element. Along with the founding father of pesantren, particularly in Java, the kyai is like a king in a small kingdom (Dhofier 1999:34).

This research focuses to examine the physical structures of pesantren and rules that have been designed to maintain and control santri within and outsides pesantren. As well, this study investigates the power and authority of pesantren leaders to perpectuate pesantren traditions and mediates the influence from outside pesantren.

Literature Review

Foucault’s (1977: 233) work on prisons argues that they work on the development of individuals or as an instrument for the transformation of individuals. Foucault asserts that prison was meant to be a mechanism similar to the school, the barracks or the hospital. The characteristics of the criminal depend on the dominant power in the area. One possibility is that power produces and affects the emergence of new objects of knowledge and accumulates new structures of information. But mechanisms of power have not commonly been studied in history. Knowledge and power are thus related and integrated. Foucault (1980:52) stressed that it is not possible to implement power without knowledge and vice versa.

In this study, Foucault‘s argument that prison is an instrument comparable with the school or hospital is key. Pesantren are Islamic schools that transform knowledge. They are also educational institutions for the transformation of individuals into ulama (Islamic scholars), ustadz/ustadzah (male/female teacher) and people who are useful in the community. The kyai has the authority to maintain pesantren related to curriculum, rules and others pesantren policy. Pesantren have regulations and mechanisms about reward and punishment. Every pesantren has different rules that depend on the kyai as a leader and dominant figure.

Foucault also developed the Panopticon concept based on Bentham’s Panopticon which explains how the design and effect of architecture functioned to control the individual (Bentham 1843). And Foucault highlights Panopticon as a system that controls inmates and as a mechanism “to induce in the inmate a state of conscious and permanent visibility that assures the automatic functioning of power” (Foucault 1977:201). This system is integrated in prisons to control the inmates and in the school dormitory to control the students. According to Foucault (1980:163), resistance to the panopticon is tactical and strategic; each offensive from one side serves as a leverage for a counter-offensive from the other. The panopticon was a strategy to better manage power being utilised in the local area in schools, barracks and hospitals.

The panopticon is evident in pesantren. For example, some schools are designed in relation to the proximity of the mosque, dormitory, house of pesantren leaders, the madrasah8 and other facilities such as mini market/shops and cafes that are integrated in one area. Some pesantren are separate from the madrasah, house of pesantren leaders, dormitory and other facilities, but each dormitory has teachers who have positions as leaders, administrative staff and mentors. This design is formulated to control

7

santri through the integration of the pesantren complex – everything and everyone is visible and potentially scrutinised. Even at home in holiday time santri must still conduct themselves according to the pesantren’s rules and the kyai or nyai (female leader/kyai’s wife) may ask parents about the attitudes and behaviours of santri.

Moreover, poststructuralist Foucauldian theory (in the field of gender and education) provides a deconstruction of dominant perspectives and develops curriculum innovation that examines gendered power/knowledge relations in schools and how these affect negotiation of the curriculum (Paechter 2001). If this power/knowledge is utilised to construct a gendered school curriculum, it will affect school subjects (Paechter 2000:32). For instance, the implementation of gendered curriculum generates inequality through social construction, where girls are stereotyped as emotional, feminine and empathetic and dominate feminine subjects such as English. On the other hand, males dominate mathematics and science which are perceived as masculine subjects because they have masculine, rational, and objective characteristics (Paechter 2000:37). Foucault’s notions were used as a tool of analysis for pesantren structures and the power of pesantren leaders in embedding and perpectuating patriarchal values. All of this was useful to examine developing and changing gender values.

Methodology

Feminists are concerned with the importance and expression of women’s lives and experiences, and their position in the social structure (Reinharz 1992:241; Maynard 2004:132; Sarantakos 2005:56; Hesse-Biber 2012:16). A feminist empiricist perspective on knowledge building also examines male views (Hesse-Biber 2012:16). This study investigates people lives in pesantren in relation to their social position and their roles as leaders (nyai), teachers, administrative staff and santri, in the hierarchical structure of pesantren. The voices and experience of men in pesantren are included in this research for the following reasons: men, particularly kyai, have great authority in maintaining and controlling of pesantren; the education processes in pesantren relate to both males and females, although the pesantren system is segregated.

This qualitative study was conducted using a participant observation approach. Qualitative research is concerned with understanding social life related to the views, meanings, opinions and perceptions of participants (Sarantakos 2005:40; Minichiello, Aroni & Hays 2008:8-9). As a participant observer, I became immersed in the daily lives of people or communities in the field (May 2001:148; Marshall & Rossman 2006:101). I stayed in pesantren and participated in pesantren activities.

One of the methods of data collection was in-depth interviews were selected by the purposive method and include: people with involvement in decision-making processes and policy in pesantren, as well students in pesantren. The details of my informants are as follows: pesantren leaders, ustadz and ustadzah, male and female santri. Other methods of data collection were direct observation and experience, collecting documentation directly from pesantren records, reports, and newsletters about curricula, teaching materials, rules, pesantren’s regulations and processes, informal discussion with pesantren members. These forms of participant observation supplemented data collected from interviews. Direct observation, semi-structured interviews and in-depth interviews were cross checked with the pesantren’s documentation or other sources.

founded in 1926 with around thirty million followers that is dominated by the rural community (Doorn-Harder 2006:2).

Findings and Discussions

This research examines two pesantren in Java (see Figure 1) with unique characteristics. Mu’allimin and Mu’allimaat in Yogyakarta is a cadre school of Muhammadiyah. Nurul Huda in Malang is a salaf pesantren that is associated with NU. They all teach Islamic studies, but they have differences related to mazhab (schools of thought in Islam), organisational affiliation and the types of leadership.

Figure 1. Map of research locations.

Pesantren Characteristics

Mu’allimin and Mu’allimaat

Mu’allimin and Mu’allimaat were founded by Kyai Haji Ahmad Dahlan, commonly known as Kyai Dahlan, in 1920 under the name Qismul Arqo or Hogere School (Senior High School) (Mu'allimaat 2009; Mu'allimin 2009:3; Mu'allimaat 2010d:2). Mu’allimin and Mu’allimaat are characterised as modern reformist and open-minded toward social and political issues in local and national spheres, as well as being open to outsiders. Moreover, Mu’allimin and Mu’allimaat are professional institutions, where teaching staff are qualified, and the role of the founder family is not dominant. Mu’allimin and Mu’allimaat segregate male and female students, not only in boarding school but in the broader school system (Mu’allimin for male students and Mu’allimaat for female students) and have a separate organisational structure. The boarding school system is also different from other pesantren in Java; in Mu’allimin and Mu’allimaat the dormitories and the house of the leader are separate. In addition, the position of the leader, ustadz/ustadzah and students have similar positions and professional relations, although the leader still has precedence. In Mu’allimin and Mu’allimaat, all have specified jobs with clear responsibilities.

Nurul Huda Pesantren

Nurul Huda is located in Singosari, a suburb of Malang, and 80 km from Surabaya, the capital of East Java. Malang is a part of East Java Province. Nurul Huda is a salaf pesantren and its genealogy can be traced to the founder of the pesantren. In this respect it is a family institution under the patriarchal control of the kyai. Nurul Huda has no government accreditation, which means the graduate certificate is not accepted by formal schools in Indonesia, hence some santri in Nurul Huda study general subjects in other schools in the neighourhood, if they want to continue in higher education (interview with Ustadz Chusin, the leader of male administrative in Nurul Huda, 6 November, 2010).

Nurul Huda has developed its own curriculum for Islamic studies and does not teach other subjects. Nurul Huda was founded in 1973 by Kyai Haji Abdul Manan Syukur, known as Kyai Manan. Since Kyai Manan’s death in March 2007, Nurul Huda has been led by his son and daughter (Wardatul 2007). The male’s pesantren is managed by his son, Kyai Khoirul, who graduated from pesantren in Java and then studied Islamic teaching in Mecca (Tohari 2009). Female pesantren is managed by the second daughter of Kyai Manan, Nyai Ummu Zahrah who studied Islamic teaching in salaf pesantren and khalaf pesantren in East Java (El-Yusufi, Hamrok & Rosyidah 2009).

Nurul Huda is characterised as being traditionalist and less open-minded toward social and political issues and outsiders than Mu’allimin and Mu’allimaat. The leader of the pesantren is like a king in a small kingdom and he is thought to have barokah (blessing or reward from God). The santri of the pesantren show great respect towards the leader. The majority of santri of Nurul Huda come from the region in East Java: Malang, Surabaya and Sidoarjo. The santri in Nurul Huda consist of students who also study MA, MTs, and universities in the neighbourhood. In 2010 there were 1126 santri studying in Nurul Huda: 46% female and 54% male (Pesantren 2010).

Pesantren: Space and Structure

funded construction. In the Mu’allimin and Mu’allimaat, financial support comes not only from the santri’s parents, but also from Muhammadiyah and its supporters.

Second, the mosque or musholla is the space for daily prayers. But in some pesantren this space also functions as a classroom or meeting room. Third, the madrasah building is the space for studying Islamic subjects and in some pesantren general subjects. Fourth, the house of the pesantren’s leader is the space in which the kyai’s/nyai’s family reside within the pesantren complex.

Mu’allimin and Mu’allimaat: Many Dormitories in Different Areas

In the Mu’allimin and Mu’allimaat, the complex consists of madrasah, mosque, and dormitories. However, the house of the leader is not located in the same area as the student dormitories or madrasah. The student dormitories are located in in different areas of Yogyakarta. Mu’allimin has ten dormitories and Mu’allimaat has thirteen dormitories (Mu'allimaat 2009; Mu'allimin 2009, 2010a). One average size room (3 x 5m) is shared by six to eight students and every student has a bed. The leader of the Mu’allimin and Mu’allimaat do not directly supervise student activities and the leader’s house is some distance from the complex, but each dormitory always has a dormitory leader (pamong) who has a position as an ustadz/ustadzah, as well as the musrif/musrifah (male/female teacher in dormitory) who manages and controls student activities in the dormitory. Pamong and musrif/musrifah reside in the dormitories and they enforce Mu’allimin and Mu’allimaat rules, but the rules however were designed by the student coordinators. Students can meet with the pamong and musrif/musrifah when they need assistance related to the rules or have difficulties with subject material in the madrasah. However, the disparate locations of these dormitories mean that management and monitoring of student activities depends on the pamong.

The Mu’allimin and Mu’allimaat only have one mosque for daily prayers and Friday prayers and the mosque is located in the same area as the Mu’allimin school building. However, all dormitories have a prayer room, which is also used to conduct other activities like reading Al-Qur’an, discussion and eating. The students have an obligation to conduct sholat berjama’ah (praying together) in the mosque or musholla, five times everyday. The imam sholat (prayer leader) is a student who schedulesprayers. As a result, every student has an opportunity to lead the prayers, which is part of their education as a Muhammadiyah cadre.

Nurul Huda Pesantren: Restricted Spaces for Female Santri

The kyai and nyai of Nurul Huda reside in the pesantren complex that consists of dormitories for male and female santri, mosque or musholla and classrooms. In Nurul Huda, the santri’s boarding school and the house of the leader are in different buildings: the female leader’s house is near the entrance to the female dormitories, and the male leader’s house is in front of the entrance to the male dormitories. The position of the leader’s houses facilitates control of the santri’s activities in the pesantren. The house of kyai and nyai is like a palace, to which only some santri have access including those who become abdi ndalem (santri who assist with domestic work in kyai/nyai’s house), santri who attend Al-Qur’an recitation class or those who are invited by the kyai/nyai. As well, the santri’s parents or guests of the pesantren cannot meet kyai/nyai in their house without an appointment; otherwise they wait in the visiting room in the female dormitories.

santri have a formal school schedule in the morning, and attend diniyah salafiyah class in the afternoon, while other santri have the formal school’s schedule in the afternoon, and they attend diniyah salafiyah

class in the morning. Classroom space has become a problem in Nurul Huda related to numerous programs and the increase in santri. Sometimes language class (Arabic and English) is conducted in the dormitories for santri who attend the bilingual program. Meanwhile, tahfidz class (Al-Qur’an recitation) is conducted in ndalem (the house of pesantren leaders) where male and female santri are in the one class, but separated.

Male and female dormitories are located in one area of the pesantren complex, but segregated. Male and female santri cannot meet together in pesantren; if they want to see each other, they must have a good reason and they can meet in the visiting room in the female dormitories. Male santri can enter the visiting space for the female dormitories, but female santri are forbidden to access male dormitories. In the dormitory female santri still wear the veil; if they do not use the veil they are punished by the senior

santri. One average size room (4 x 6m) is shared between twenty or thirty santri; some sleep in the front of the bedroom because there is not enough space. They sleep on the floor with thin mattresses which can be folded. Their attitude and behaviour in dormitories is regulated by pesantren rules that are designed by Nurul Huda’s leader. The kyai and nyai have great authority and control over the santri, because they reside in one area.

Rules of Pesantren: Monitoring and Controlling Santri’s Activities

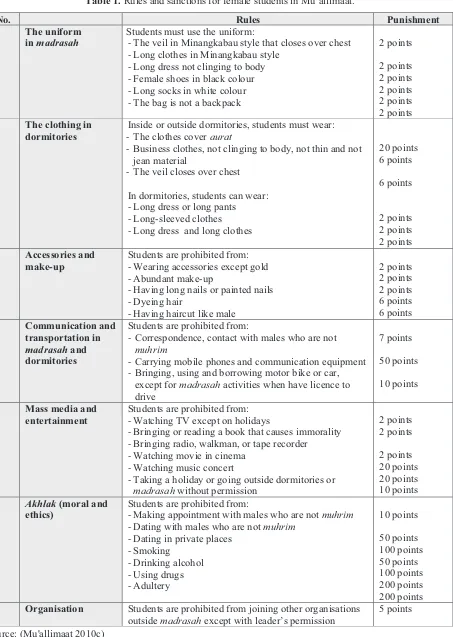

The rules of the pesantren are designed to internalise and socialise Islamic values in the santri. These rules regulate all aspects of student activities and the santri must follow them. These rules describe the hidden curriculum and ideology of the pesantren. For example, rules about aqidah (Islamic belief) in Mu’allimin (see Table 2) assert that the Mu’allimin as a Muhammadiyah school follows the Hambali

mazhab that permits no accommodation between local traditions and Islamic values and differs from the Syafi’i mazhab, followed by the NU pesantren, which accepts these accomodations (Abdullah 1997:50). The aqidah rules, particularly related to ziarah and tahlillan, show the differences in mazhab between Muhammadiyah and NU pesantren where Nurul Huda conduct these traditions.

In terms of clothing rules, particularly for female santri, the differences in the two pesantren

represent respective gender values and ideology in interpreting Islamic teaching related to women’s aurat. Female santri are permitted to wear long pants, but when they have a class in the dormitories, they must wear a long dress in Moslem style. The santri’s attitude and behaviour in dormitories is regulated by

pesantren rules that are designed by the pesantren’s leader in the Nurul Huda, whilst in the Mu’allimin and Mu’allimaat, rules are implemented by the student coordinator and pamong.

Mu’allimin and Mu’allimaat: Flexibility Only for Male Students

under the control of ustadz/ustadzah and pamong, whereas students who have more than 100 punishment points are under the control of the leader of Mu’allimin and Mu’allimaat; if students have 151 to 200 points, they must attend a special conference that decides whether they should be expelled and they are asked to write a resignation letter from madrasah (interview with Ustadzah Fauziah, the director of Mu’allimaat, 5 October, 2010).

The clothing styles and colours for the Mu’allimin and Mu’allimaat students are different from student uniforms in other Islamic schools, and distinguishes them from their contemporaries in the community outside the pesantren where Javanese style clothing is common. The clothing rules embed stereotypes of masculinity and femininity, particularly if a female student is prohibited from wearing pants, jeans and sport shoes; this is because these items are considered male attire (see Table 2). Female students can wear pants and sport shoes when they have sport classes in the madrasah. These rules were introduced about five years ago by the student coordinator in the Mu’allimaat, Ustadzah Rita, who had studied in Cairo. Before she became a student coordinator, female students could wear pants, sport shoes and carry a backpack; even the character of female students tended to be masculine (Interview with Ustadzah Fitri, musrifah in Mu’allimaat, 25 September, 2010).

Some of the ustadzah in the Mu’allimaat also disagree with the new rules that they consider unimportant, particularly related to wearing sport shoes and backpacks, and one of the ustadzah always carries a backpack in the madrasah as an expression of her dissatisfaction with these rules. She feels very disappointed that changes to the rules have not been clarified with female students, as stated by Ustadzah Misma:

The rules are explained to the female students, for example: why can’t they wear jeans? Why can’t they wear trousers? These are personal things not related to masculine and feminine; this is how, I explain it to them. But, sometimes there are limits to our capabilities to help the female students understand. Why are they are prohibited to wear jeans? Because jeans are untidy as they are wore often. This is related to how they are used and not related to the Islamic law which forbids jeans, no! The rules in the Mu’allimaat prohibit female student to wear long pants, but they often meet me with a different style of dress that includes long pants. They do not ask me, because they know my views. (Interview with Ustadzah Misma, female teacher in Mu’allimaat, 2 October, 2010)

The controversial issue about the rules in Mu’allimaat is related to the differences in ideology between teachers and the student coordinator. As a cadre school of the Muhammadiyah, the Mu’allimaat has many teachers who are members of the Muhammadiyah, while the student coordinator is associated with the PKS (Partai Keadilan Sejahtera/Prosperous Justice Party) that has a different ideology from Muhammadiyah. In addition, the differences between the Muhammadiyah and the PKS has been the subject of books written by Muhammadiyah members, who argue that Muhammadiyah has a different ideology from the PKS and that Muhammadiyah, as an independent organisation, should not accept that Muhammadiyah is used for political purposes (Nashir 2007:44-51; Asy'ari 2009). However, some of the Mu’allimaat teachers and staff are associated with PKS. The ideology of PKS is embedded in Mu’allimaat’s rules that effectively internalise the PKS ideology; under the influence of the PKS, clothing rules for female students impose an Egyptian style of Islamic clothing. In the Mu’allimin, some of the teachers are also associated with PKS, but the coordinators in the madrasah are Muhammadiyah cadre, and the values of the Muhammadiyah are reflected in the Mu’allimin’s rules.

Table 1. Rules and sanctions for female students in Mu’allimaat.

No. Rules Punishment

1 The uniform in madrasah

Students must use the uniform:

Ͳ The veil in Minangkabau style that closes over chest Ͳ Long clothes in Minangkabau style

Ͳ Business clothes, not clinging to body, not thin and not jean material

Ͳ Having long nails or painted nails Ͳ Dyeing hair

Ͳ Correspondence, contact with males who are not muhrim

Ͳ Carrying mobile phones and communication equipment Ͳ Bringing, using and borrowing motor bike or car,

except for madrasah activities when have licence to drive

Ͳ Bringing or reading a book that causes immorality Ͳ Bringing radio, walkman, or tape recorder

Ͳ Watching movie in cinema Ͳ Watching music concert

Ͳ Taking a holiday or going outside dormitories or madrasah without permission

Ͳ Making appointment with males who are not muhrim Ͳ Dating with males who are not muhrim

Ͳ Dating in private places 7 Organisation Students are prohibited from joining other organisations

outside madrasah except with leader’s permission

5 points

Table 2. Rules and sanctions for male students in Mu’allimin.

No. Rules Punishment

1 The uniform in madrasah

Students must use the uniform:

Ͳ Long-sleeved shirt with trousers and black peci

(Indonesian headgear)

3 Accessories Students are prohibited from:

Ͳ Using ring, choker, bangle or similar

Ͳ Correspondence or contact with females who are not muhrim

Ͳ Dating with males who are not muhrim Ͳ Smoking

Ͳ Watching TV except on holiday or outside the dormitories

Ͳ Bringing or reading books that cause immorality

Ͳ Bringing radio, walkman, or tape recorder

Ͳ Watching movie in cinema

Ͳ Watching music concert

Ͳ Taking a holiday or going outside the dormitories or madrasah without permission

Ͳ Watching blue film or pornography on internet

20 points

Ͳ Having something that is assumed to be mystic

Ͳ Visits to graves (ziarah)

Ͳ Attending slametan for people’s death (tahlilan)

50 points

The differences between the Mu’allimin and Mu’allimaat are not only related to rules, but also school and dormitories facilities, the quality of teachers and the cadre system (informal discussion with Mu’allimaat students, 1 October, 2010). All these aspects affect on Mu’allimin regulations and the education system in Mu’allimin. Male students have access to newspapers, TV or radio, but can also access good books from the Muallimin’s library and information from Mu’allimin’s colleagues, even from Muhammadiyah leaders. Female students have limited information from the Muhammadiyah or Aisyiyah (women’s organisation in Muhammadiyah), although they can access newspapers every day, and watch TV once a week. The Mu’allimin students have more opportunity for wider discussion with other people outside the pesantren, and the rules in Mu’allimin are more relaxed, it means they can do everything and they can meet girls and chat with them, so they can express their ideas (Interview with Ustadzah Fitri, musrifah in Mu’allimaat, 25 September, 2010)

The female students are aware of the gender discrimination between male and female students. Faiza, a student in Mu’allimaat who is also a journalist in the Mu’allimaat magazine, resents the restrictions placed on female students:

I feel greatly the differences between the Mu’allimin and Mu’allimaat. The Mu’allimin is very free. I asked the director of the Mu’allimin: “what is wrong with our sex? Is it because we are girls, we do not go to anywhere; we must stay in dormitory and madrasah all day. Why is the reason always because we are girls? Is it that a woman cannot lead? If someday a woman is a leader, does this mean that judgement day (kiamat) is near?” (Interview with Faiza, student in Mu’allimaat, 5 October, 2010)

Although in the Mu’allimaat, the female leader does not agree with gender equity and the only a minority of teachers support women’s empowerment, gender awareness among female students emerges from a recognition of discriminatory rules between students in the Mu’allimin and Mu’allimaat. Female students want the Mu’allimaat leaders, particularly the student coordinator, to provide greater autonomy and self-reliance (Interview with Ema, student in Mu’allimaat, 5 October, 2010).

The Mu’allimaat students not only criticize Mu’allimaat rules (particularly about clothing and restrictions on their mobility outside the complex, which they consider discriminatory between male and female students), but also they desire to express their ideas and have greater freedom of movement. The Mu’allimaat rules prohibit students from joining other organisations outside the Mu’allimaat (see Table 1). This rule also applies to musrifah who are expected to focus on educating students in dormitories. Musrifah should not be distracted by involvement in organisations outside the Mu’allimaat, even students’ organisations in their university, although this rule is ignored by some (interview with Ustadzah Fitri, musrifah in Mu’allimaat, 3 October, 2010).

Actually, male students also have the same opinions about the discriminatory rules between the Mu’allimin and Mu’allimaat. The Mu’allimin students can negotiate with pamong and musrif about the rules in Mu’allimin, and musrif will often reduce the obligations in the pesantren for those students thought to be responsible (Interview with Ave, student in Mu’allimin, 30 September, 2010).

The Mu’allimin rules are easily broken because of its location to a city with plural urban culture. Ustadz Mahdi, musrif in the Mu’allimin, related how these circumstances make the enforcement of the Mu’allimin’s rules difficult:

Usually a pesantren is located in one area, but the Mu’allimin is different, with the dormitories are scattered throughout the city, and this creates many temptations. For example, student go to an internet cafe and access something forbidden, or go to Malioboro (a shopping strip) and drink alcohol, without anyone knowing. (Interview with Ustadz Mahdi, musrif in Mu’allimin, 30 September, 2010)

Nurul Huda Pesantren: Male Santri can Negotiate more than Female Santri

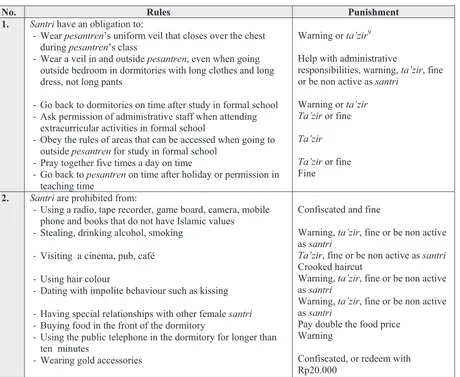

it is keen to controll the santri’s activities outside the pesantren. For example, Nurul Huda determines the time santri have to return to the dormitories after school classes. Also when santri attend extracurricular activities in the school they must ask permission from the administrative staff (see Table 3).

Table 3. Rules and sanctions for female santri in the Nurul Huda Pesantren.

No. Rules Punishment

1. Santri have an obligation to:

ͲWear pesantren’s uniform veil that closes over the chest during pesantren’s class

ͲWear a veil in and outside pesantren, even when going outside bedroom in dormitories with long clothes and long dress, not long pants

ͲGo back to dormitories on time after study in formal school ͲAsk permission of administrative staff when attending

extracurricular activities in formal school

ͲObey the rules of areas that can be accessed when going to outside pesantren for study in formal school

ͲPray together five times a day on time

ͲGo back to pesantren on time after holiday or permission in teaching time

ͲUsing a radio, tape recorder, game board, camera, mobile phone and books that do not have Islamic values

ͲStealing, drinking alcohol, smoking

ͲVisiting a cinema, pub, café

ͲUsing hair colour

ͲDating with impolite behaviour such as kissing

ͲHaving special relationships with other female santri ͲBuying food in the front of the dormitory

ͲUsing the public telephone in the dormitory for longer than ten minutes

ͲWearing gold accessories

Confiscated and fine

Warning, ta’zir, fine or be non active as santri

Ta’zir, fine or be non active as santri Crooked haircut

Source: (Pesantren 2009b, 2009a); Note: $AUS 1 = Rp 9000

Nurul Huda has rules related to clothing, the timetable in the boarding school, use of electronic devices, and diniyah salafiyah class, qiro’ati class, tahfidz class, and Arabic and English language class. Every class or program in Nurul Huda has rules and sanctions when santri disobey rules. The clothing rules for females, for example, are the strictest among the pesantren in this research: female santri must not only wear the veil inside and outside the pesantren, but also outside the bedroom in dormitories, perhaps because female dormitorycan be accessed by male santri who also work as cooking staff in the female dormitories known as abdi ndalem. Female santri are prohibited from wearing long pants in the dormitories, whereas male santri must wear long-sleeved shirts, sarung and peci in the pesantren. Usually, they wear trousers if they go to school or sports activities.The clothing rules of Nurul Huda are

9

different from other local pesantren and Moslem society around this pesantren. However, when the santri

from Nurul Huda attend classes in the madrasah they have to follow the clothing rules of the madrasah.

The changing rules in relation to female santri happened two years ago during new administrative staff changes in the female pesantren. The new rules must be reported to the pesantren’s leader and have agreement from the leader, as explained by Ustazdah Wulan, the female leader of administrative staff in Nurul Huda.

In the past, female santri were able to use electronic devices and watch movies in the dormitories during the one week holiday known as masa ruhshoh, but during this research, these rules have not been implemented, because they were though to have a negative effect. Ustadzah Wulan, the leader of female administrative staff, as well asa teacher in diniyah salafiyah class and santri in Al-Qur’an recitation related:

In the past, the female santri were permitted to use cameras and radios, also they could watch movies. After the exams, they did not have activities, so it was refreshing. Usually, the electronic devices were brought by their parents when visiting the pesantren. But, these things had negative effects; as a result these programs were cancelled. We review the programs of previous administrative staff, and every two years we evaluate programs and rules in the pesantren (Interview with Ustadzah Wulan, the leader of female administrative in Nurul Huda, 5 November, 2010)

According to Azizah, female santri and teacher in qiro’ati class in Nurul Huda, Masa ruhshoh is no longer permitted, because the female santri watched movies until 1:00, and the next day many santri did not attend prayers together at Subuh time (Interview 5 November, 2010). The perceived negative effects of masa ruhshoh prompted a tightening of the pesantren’s rules, and a renewed effort to educate female

santri about Islamic teaching. Not all infringement of rules by santri are known about by pesantren

leaders or administrative staff. Some of the santri endeavour to avoid detection, by, for example, leaving their mobile phone with the owner of a small shop near the pesantren; before going to madrasah, they collect their mobile phone from the shopkeeper and after finishing their study in the madrasah, they return it to the shopkeeper (fieldwork notes, 8 November, 2010). They pay the owner of the small shop to keep their mobile phone, but also for keeping their secret from other santri and administrative staff (interview with Fina, female santri in Nurul Huda, 9 November, 2010).

The rules for female santri have become stricter and they were more comfortable with the old rules, because they could schedule time outside the pesantren every week. Meanwhile, the male santri have greater freedom. They can have dinner outside the pesantren while the female santri have both breakfast and dinner in the pesantren, as cooked by male santri in their role as abdi ndalem. Female santri must return to the pesantren by 17:00, while the male santri have greater freedom in leaving the pesantren at night (Interview with Azizah and Yasmin, female santri in Nurul Huda, 5 November, 2010).

The implementation of pesantren rules for male santri is less strict. The female santri who have privileges and rights are those who work as teachers and administrative staff in the pesantren, but this is still limited as compared to male santri. For example, it is prohibited to carry a mobile phone (see Tables 3 and 4), but administrative staff are given one mobile phone to co-ordinate their activities with the female leader and undertake their responsibilities. In contrast, almost all male santri who have work as a teacher or administrative staff have a mobile phone.

According to Yusril and Ustadz Chusin (the leader of administrative staff), the rules for male santri

are not strict like for female santri, and male santri still have the opportunity to negotiate the rules with the pesantren leader. For example, watching of movies in dormitories was prohibited by the kyai, but male administrative staff negotiated with the kyai to permit watching soccer matches on television. The male administrative staff endeavour to minimise santri going outside pesantren in the evening. The male

santri can watch movies in the dormitories once a month, mostly Islamic movies chosen by the administrative staff. However, as explained by Yusril these rules are there to be broken. For example:

Table 4 Rules and sanctions for male santri in the Nurul Huda Pesantren.

No. Rules Punishment

1. Santri have obligation to:

Ͳ Wear pesantren’s uniform10 during pesantren’s class

Ͳ Wear casual clothes, sarung and peci in and outside pesantren

Ͳ Return to the dormitories after school classes

Ͳ Ask permission from administrative staff when attending extracurricular activities at school

Ͳ Obey the rules when going outside pesantren for study at school

Ͳ Pray together five times a day on time and wear a white long sleeved shirt

Ͳ Return to the pesantren on time after holidays

Warning or ta’zir Warning or ta’zir Ta’zir or get fine Ta’zir

Ta’zir or get fine

Ta’zir

Fine 2. Santri are prohibited from:

Ͳ Using a radio, tape recorder, game board, camera, mobile phone and books that do not have Islamic values

Ͳ Stealing, drinking alcohol,gambling, smoking

Ͳ Watching music concert

Ͳ Visiting a cinema, pub, or café

Ͳ Dating with impolite behaviour such as kissing

Ͳ Using public telephone in dormitory for longer than ten minutes

Confiscated and fine

Warning, ta’zir, fine or be non active as santri

Warning, ta’zir or fine Ta’zir, fine or be non active as santri

Ta’zir or be non active as santri Warning

Source: (Pesantren 2009b, 2009a)

The differences in rules are not only between male and female santri, but also between junior and senior santri. For example, a santri who is twenty years old can smoke at certain times and in certain places as explained by a senior santri:

There have been some changes in the rules here. Previously, santri were prohibited from smoking. Now, santri can smoke when they are 20 years old. The smoking has to be discreet and not seen by younger santri; it can’t be blatant. Like in a small quiet cafe where there are no younger santri. If there are younger santri, it is prohibited to smoke. There could be jealousy and it gives a bad example which could be followed when they are adults. (Interview with Yusril, male santri and teacher in qiro’ati class in Nurul Huda, 10 November, 2010)

The pattern of change in regulations for male santri in Nurul Huda is different from the female santri. Change in the latter is produced through evaluation, while the regulations for male santri are determined by the leader’s attitudes. The founder of the pesantren, Kyai Manan did not smoke, so smoking was prohibited for santri, but the current leader smokes, so santri over twenty years old can smoke (Interview with Ustadz Chusin, the leader of male administrative staff in Nurul Huda, 12 November, 2010).

The differentiation between male and female santri is also related to classroom activities. In the tahfidz class, the male santri have an ustadz who listens to recitations of the Al-Qur’an before they recite for the kyai, while female santri do not have an ustadzah as a tutor; usually they listen to each other before reciting for the kyai. In language class, male santri have an ustadz who uses creative and fun methods, such as singing and playing games until midnight, while the language class for female santri only involves memorising the words and conversation.

10

During the holidays, the female santri usually clean the dormitories and they still have extracurricular activities at night such as qiro’ah (the art of reading Al-Qur’an) and kaligrafi (the art of writing in the Arabic script) class. The male santri however have sport activities outside the pesantren such as soccer and badminton. The female santri only have time on Friday to visit the graves of the kyai/nyai, while the male santri can visit these graves anytime. The grave visits denotes the charisma of the kyai, in the belief that santri will find barokah (blessing or reward from God).

The structures in the pesantren rules have been developed to educate and internalise Islamic teaching in santri. The two pesantren have similar rules related to clothing, mobility, communication, mass media and entertainment. Pesantren leaders seek to manage and constrain influences from outside the pesantren that, they believe, have a negative effect on the santri. These rules and regulations regarding clothing, though different in each pesantren, reflect Islamic values and the pesantren’s identity that distinguish it from the society outside. The infrastructure of the pesantren complex together with the rules seeks to perpetuate the pesantren’s traditions and sustain the authority of kyai.

Foucault (1980:39) described the system in a military school to control army cadets or in prison to control inmates, where the panopticon is used as a strategy to exercise power within an institution. These pesantren resemble Foucault’s panopticon, not only related to the pesantren physical structures of the dormitories, house of the leader, mosque, and the school located in one area, but also related to the rules in a pesantren which are designed to integrate class rules with those of the everyday lives of the santri. Some of the pesantren rules are based on Islamic values, for example: clothing, aqidah and akhlak, and some rules reflect the personal habits and experiences of the leaders. The rules about smoking in Nurul Huda, for example, changed with the kyai and his personal habits. The more restrictive regulations of the other pesantren suggest less familiarity with the world outside the pesantren and associated anxieties about external influences. The integrated system in the pesantren explains how the leaders exercise their authority and the santri always obey. The pesantren complex and rules in the three pesantren in this study are designed like a panopticon.

The panopticon system in the pesantren has a gender bias; the rules and complex system create more opportunity for male santri to access information and knowledge. According to Walby (1990:92), educational institutions continue to embed gender difference through the formal curriculum or hidden curriculum. A similar situation prevails in the pesantren complex and rules, which tend to construct gender bias, also create gender awareness among the female santri, who question why male and female santri have different opportunities and rules in the pesantren. The critical thinking of female santri in the pesantren, where the leader has not developed gender equity, is more evident than in the pesantren where there is a leader promoting gender awareness, because female students are marginalised and subordinated.

Conclusion

Resembling Foucault’s Panopticon that based on Bentham’s concept, the discussion of pesantren physical infrastructure and rules show how the kyai’s authority is used to control santri – a system that “controls the people or a mechanism to induce in the people a conscious and permanent visibility that assures the automatic functioning of power; the resistances to the panopticon are tactical and strategic terms in which each offensive from the one side serves as leverage for a counter-offensive from another” (Foucault 1980:163). The Panopticon system is integrated between pesantren rules in madrasah and dormitories.

structures and the segregation between male and female santri determined by pesantren leaders, and this seems very effective in perpetuating the patriarchal system and pesantren traditions.

Bibliography

1. Abdullah, AR 1997, Pemikiran Islam di Malaysia: Sejarah dan Aliran, Gema Insani Press, Jakarta.

2. Asy'ari, S 2009, Nalar Politik NU dan Muhammadiyah: Over Crossing Javanese Sentris, LKiS, Yogyakarta.

3. Azra, A, Afrianty, D & Hefner, RW 2007, 'Pesantren and Madrasa: Muslim Schools and National Ideals in

Indonesia', in RW Hefner & MQ Zaman (eds), Schooling Islam: The Culture and Politics of Modern Muslim

Education, Princenton University Press, Princeton and Oxford, pp. 172–98.

4. Bentham, J 1843, The Works of Jeremy Bentham, ed. J Bowring, W. Tait, Simpkin.

5. Dahlan, M 2002, 'Sholihah A. Wahid Hasyim: Teladan Kaum Perempuan Nahdliyin', in J Burhanudin (ed.),

Ulama Perempuan Indonesia, Gramedia Pustaka Utama, Jakarta, pp. 100-37.

6. Dhofier, Z 1999, The Pesantren Tradition: The Roles of The Kyai in the Maintenance of Traditional Islam in

Java, The Program of Southeast Asian Studies, Arizona.

7. Doorn-Harder, Pv 2006, Women Shaping Islam: Indonesia Women Reading the Qur'an, University of Illinois

press, Urbana and Chicago.

8. El-Yusufi, DN, Hamrok, W & Rosyidah, A 2009, 'Beratnya Mengemban Amanah Orang Tua', Nurul Huda, pp.

15–6.

9. Endang, T 2005, 'Struggling for the Umma: Changing Leadership Roles of Kiai in Jombang, East Java', The

Australian National University.

10. Fealy, G 1996, 'Wahab Chasbullah, Traditionalsm and The Political Development of Nahdhatul Ulama', in G

Barton & G Fealy (eds), Nahdlatul Ulama, Traditional Islam and Modernity in Indonesia, Monash Asia

Institute, Clayton, Victoria, pp. 1–41.

11. Foucault, M 1977, Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison, Vintage Books, New York.

12. —— 1980, Power/Knowledge, The Harvester Press, Suffolk.

13. Hesse-Biber, SN 2012, 'Feminist Research: Exploring, Interrogating, and Transforming the Interconnections of

Epistemology, Methodology and Method', in SN Hesse-Biber (ed.), Handbook of Feminist Research : Theory

and praxis, 2nd edn, Sage, Los Angeles, London, pp. 2–26.

14. DJPI-KAR Indonesia 2008a, Daftar Alamat Pondok Pesantren Tahun 2008/2009, by Indonesia, DJPI-KAR,

Direktorat Jenderal Pendidikan Islam - Kementerian Agama Republik Indonesia.

15. DJPI-KAR Indonesia 2008b, Jumlah Santri dan Nama Kyai Tahun 2008/2009, by ——, Direktorat Jenderal

Pendidikan Islam - Kementerian Agama Republik Indonesia.

16. Jabali, F & Subhan, A 2007, 'A New Form of Contemporary Islam in Indonesia', in R Sukma & C Joewono

(eds), Islamic Thought and Movements in Contemporary Indonesia, Kanisius, Yogyakarta, pp. 54–78.

17. Karim, AG 2008, 'Pesantren in Power: Religious Institutions and Political Recruitment in Sumenap, Madura

[Paper in: Islamic Education in Indonesia.]', Review of Indonesian and Malaysian Affairs, vol. 42, no. 1, pp.

157-84.

18. Kholifah, S 2005, 'Wacana Santri Perempuan tentang Politik', Universitas Airlangga.

19. Marshall, C & Rossman, GB 2006, Designing Qualitative Research, Fourth edition edn, Sage Publication,

Thousand Oaks, London and New Delhi.

20. May, T 2001, Social Research: Issues, Methods and Process, Open University Press, Bungkingham,

Philadelphia.

21. Maynard, M 2004, 'Feminist Issues in Data Analysis', in M Hardy & A Bryman (eds), Handbook of Data

Analysis, Sage, Los Angeles, London, New Delhi, Singapore, Washington DC, pp. 131–45.

22. Minichiello, V, Aroni, R & Hays, T 2008, In-depth Interviewing, Pearson, Sydney.

23. Mu'allimaat, M 2009, Profil Madrasah Mu'allimaat Muhammadiyah Yogyakarta, Madrasah Mu'allimaat,

Yogyakarta.

24. —— 2010a, Data Pendidikan Orang Tua Siswi Madrasah Mu'allimaat Tahun Pelajaran 2010/2011, Madrasah

25. —— 2010b, Data Siswi Madrasah Mu'allimaat Tahun Pelajaran 2010/2011, Madrasah Mu'allimaat, Yogyakarta.

26. —— 2010c, Pedoman Pelaksanaan Tata Tertib Siswi, Madrasah Mu'allimaat, Yogyakarta. 27. —— 2010d, Sejarah Mu'allimaat, Madrasah Mu'allimaat, August 29, 2009.

28. Mu'allimin, M 2009, Pedoman Pembinaan Siswa Madrasah Mu'allimin Muhammadiyah Yogyakarta, Madrasah Mu'allimin, Yogyakarta.

29. —— 2010a, Buku Panduan Siswa Madrasah Mu'allimin Muhammadiyah Yogyakarta Tahun Pelajaran 2010-2011, Madrasah Mu'allimin, Yogyakarta.

30. —— 2010b, Data Pendidikan Orang Tua Siswa Madrasah Mu'allimin Tahun Pelajaran 2010/2011, Madrasah Mu'allimin, Yogyakarta.

31. —— 2010c, Data Siswa Madrasah Mu'allimin Tahun Pelajaran 2010/2011, Madrasah Mu'allimin, Yogyakarta. 32. Muttaqin, F 2008, 'Proggresive Muslim Feminists in Indonesia from Pioneering to the Next Agenda', Ohio

University.

33. Nashir, H 2007, Manifestasi Gerakan Tarbiyah: Bagaimana Sikap Muhammadiyah?, sixth edn, Suara Muhammadiyah, Yogyakarta.

34. O’Hanlon, MG 2006, 'Pesantren dan Dunia Pemikiran Santri: Problematika Metodologi Penelitian Yang Dihadapi Orang Asing', Muhammadiyah University.

35. Paechter, C 2000, Changing School Subjects: Power, Gender and Curriculum, Open University Press, Buckingham, Philadelphia.

36. —— 2001, 'Using Poststructuralist Ideas in Gender Theory and Research', in B Francis & C Skelton (eds), Investigating Gender: Contemporary Perspectives in Education, Open University Press, Buckingham, Philadelphia, pp. 41–51.

37. Pesantren, NH 2009a, Laporan Pertanggungjawaban Pengurus Putra-Putri Masa Khitmad 2007-2009, Nurul Huda Pesantren, Malang.

38. —— 2009b, Program Kerja Pengurus Pondok Pesantren Al-Qur'an Nurul Huda Masa Khidmat 2009-2011, Nurul Huda Pesantren, Malang.

39. —— 2010, Data Rekapitulasi Jumlah Santri, Nurul Huda Pesantren, Malang.

40. Reinharz, S 1992, Feminist Methods in Social Research, Oxford University Press, New York.

41. Ricklefs, MC 2008, A History of Modern Indonesia Since c.1200 Stanford University Press, Stanford, Calif. 42. Sarantakos, S 2005, Social Research, Palgrave Macmillan, New York

43. Srimulyani, E 2008, 'Pesantren Seblak of Jombang, East Java: Women's Educational Leadership [Paper in: Islamic Education in Indonesia.]', Review of Indonesian and Malaysian Affairs, vol. 42, no. 1, pp. 81–106. 44. Tohari, H 2009, 'Kyai Muda yang Haus Ilmu', Nurul Huda, pp. 13–4.

45. Wagiman, S 1997, 'The Modernization of the Pesantren's Educational System to Meet the Needs of Indonesian Communities', McGill University.