SOCIOLOGY AND WELFARE

DEVELOPMENT

Edited by:

Muhamad Fadhil Nurdin

Centre for Socioglobal Studies Padjadjaran University

Foreword by:

Dr. Afriadi Sjahbana Hasibuan, MPA, M.Com (Ec)

SOCIOLOGY AND WELFARE DEVELOPMENT © 2015 Muhamad Fadhil Nurdin et. al.

First Published May, 2015

Published By

Centre for Socioglobal Studies Padjadjaran University

In Cooperation With

Penerbit Samudra Biru (Member of IKAPI)

Jomblangan Gg. Ontoseno Blok B No 15 Rt 12/30 Banguntapan Bantul Yogyakarta Indonesia 55198 Telp. (0274) 9494 558

E-mail/FB: [email protected]

ISBN: 978-602-9276-56-5

CONTENTS

Contents ... iii

List of Contributors ... v

Acknowledgement ... ix

Foreword ... xi

Introduction ... xiii

Chapter 1 Welfare Development: Meanings, Issues and Challenges Muhamad Fadhil Nurdin ... 1

Chapter 2 Poverty and Social Development Muhamad Fadhil Nurdin, Ali Maksum, Indri Indarwati ... 19

Chapter 3 The Emergence of Jakarta-Bandung Mega-Urban Region and Its Future Challenges Agung Mahesa Himawan Dorodjatoen, Forina Lestari and Muhamad Fadhil Nurdin .... 39

Chapter 5

Baitul Mal wat Tamwil: a Sociological and Social Welfare Movement ?

Hery Wibowo & Muhamad Fadhil Nurdin ... 79

Chapter 6

Environmental Participation among Youth: Challenges, Issues and Motivating Factors

Lim Jen Zen & Muhamad Fadhil Nurdin ... 97

Chapter 7

Indonesian Workers Health Condition: A Sociological Analysis

Bintarsih Sekarningrum, Desi Yunita

and Muhamad Fadhil Nurdin ... 125

Chapter 8

he Delivery System of Education Programs

Mahathir Yahaya, Ali Maksum,

Muhamad Fadhil Nurdin and Azlinda Azman ... 135

Chapter 9

Child Brides, Not Our Pride:

Looking Into Child Marriage Incidences in Malaysia

Mitshel Lino, Muhamad Fadhil Nurdin and

Azlinda Azman ... 143

Chapter 10 Concluding Remarks

LiSt of ContribUtorS

Agung Mahesa Himawan Dorodjatoen, is aPhD candidate at West Australia University, Perth – Australia. He is a Planning Staf, Directorate of Spatial Planning and Land Afairs, Indonesia National Development Planning Agency (Bappenas). He is a Best Graduate Student in Regional and Planning Department, Bandung Institute of Technology (2006) and Utrecht Excellence Scholarships Awardee 2007-2009 on Research Master Human Geography & Planning, Faculy of Geoscience, Utrecht University.

Ali Maksum, is a Ph.D candidate at the Centre for Policy Research and International Studies (CenPRIS), Universiti Sains Malaysia, Penang. His current project is about the Indonesia-Malaysia relations from defensive realism perspective. He has written articles have been published in such publisher as Kajian Malaysia: Journal of Malaysian Studies, Springer (ISI), Indonesia national newspapers and conferences.

HIV/AIDS and drug related issues.

Bintarsih Sekarningrum, a leturer at Social Welfare Departement in Social and Political Sciences Faculty, University of Padjadjaran. She obtained Bachelor degree, master degree and Doctoral degree from University of Padjadjaran. Some scientiic papers had been published at national or international level. Currently, he is focusing on waste management problem in society who life near the Cikapundung river at Bandung City.

Desi Yunita, oicially join the Departemen of Sociology at Social and Political Science Faculty University of Padjadjaran since 2014. She got Magister degree in Sociology also from University of Padjadjaran and focusing the research on development and environmental problem.

Forina Lestari, obtainedB.Sc.Eng. (ITB, 2006), MSc in Housing, School of Housing, Building and Planning, University of Science Malaysia (USM, 2008). Lecturer at Indonesian Institute of Technology (ITI). She has published a book: Alam Takambang Jadi Guru: Merajut Kearifan Lokal dalam Penanggulangan Bencana di Sumatera. Consultant and expertise at Directorate of Rural and Urban Afairs, Indonesia National Development Planning Agency (Bappenas) and Directorate General of Spatial Planning, Ministry of Public Works(2013), Directorate General of Regional Development Assistance, Ministry of Home Afairs and Expert, Deputy of the Area Development, Ministry of Public Housing (2012), Expert Staf, Commission V (Infrastructure), he Indonesian House of Representatives (DPR, 2011). Junior Expert, Directorate of Rural and Urban Afairs, Indonesia National Development Planning Agency (Bappenas, 2010).

Hery Wibowo, S.Psi, MM, PhD isa leturer at Departement of Social Welfare Faculty of Social and Political Science, Padjadjaran University.

Mitshel Lino is a Master of Social Sciences (Psychology) candidate under the supervision of Assoc. Prof. Dr. Intan Hashimah Mohd Hashim from the Department of Social Work, Universiti Sains Malaysia. Her research interest surrounds the ield of Social Psychology. She was a Graduate Assistant, serving as a Psychology tutor in the university. She was invited to the Golden Key International Honour Society for academic excellence and awarded Second Upper Class Honours from her undergraduate. Her past researches included the area of Multicultural Psychology and Child Marriage in Malaysia, collaboration project with UNICEF.

Mohd. Haizzan Yahaya MSW is Ph.D scholars from University Sains Malaysia. He is currently researching on Urban Poor Housing and being supervised by. Muhamad Fadhil Nurdin, PhD and associate professor Azlinda Azman, PhD

Mohd Tauik Mohammad is a Ph.D scholar at the Social Work Programme, School of Social Sciences, Universiti Sains Malaysia. His current Ph.D studies regarding on Specialization Social Work, Forensic Social Work/Victims’ Studies/Restorative Justice, being supervised by associate professor Azlinda Azman, PhD.

Muhamad Fadhil Nurdin, MA and Ph.D. from University of Malaya. He is a leturer at Departement of Social Welfare (1982-2011) and Departement of Sociology (2011-present), Head Departement of Sociology in Faculty of Social and Political Science, Padjadjaran University (2014- present). Visiting Associate Professor at University of Malaya (2008) and Visiting Associate Professor at Univerisiti Sains Malaysia (2012- present).

Current Public Services are Facilitator, Comprehensive Maternal Village Program in West Java, West Java Province Health Department (2006 – 2008), Facilitator for Sustainable Capacity Building for Decentralization (SCBD) Project in Bau-bau City and Buton Regency (2008 – 2012), District Advisory Team Capacity Building Program Minimum Service Standard Basic Education at Sorong West Papua (2014-2016), tdevianty@ rocketmail.com.

ACknowLedgement

Alhamdulillah. hanks to Allah SWT, whom with His willing giving me the opportunity to complete this book entitled Sociology and Welfare Development. he publication of this book would not have been possible without the guidance and knowledge wich I have acquired from my honourable professors; Professor A.D Saefullah - University of Padjadjaran and Professor Abd. Hadi Zakaria - University of Malaya. I would also like to dedicate this book to my beloved wife, Tuty Tohri and our lovely children Tofan Rakhmat Zaky, Forina Lestari, Fitaha Aini and Tamal Arief Ihsan - their support in my life.

he publication of this book would not be possible without the assistance and cooperation that we have received over the years from the many individuals and organization in various parts of the world. In particular, we wish to thank our team, all authors - Department of Sociology Padjadjaran University and Universiti Sains Malaysia. Specially thanks especially to Ali Maksum for his excellent assistance during the editorial process of this book. Dr. Arry Bainus the Dean of Faculty of Social and Political Sciences, Padjadjaran University. All of my Masters-PhD students and colleagues at Padjadjaran University as well as USM whom I would like to thanked for providing continuous support towards my success.

Wassalam.

foreword

Dr. Afriadi Sjahbana Hasibuan, MPA, M.Com (Ec)

Head of Research&Development Ministry of Home Afairs,Republic ofIndonesia

First of all, I am honored to write this foreword and to give my warm endorsement to this book edited by my colleague Muhamad Fadhil Nurdin, Ph.D. In my point of view, Indonesian harmony is urgent and should be achieved soon. he government and all stakeholders are pushed to react and formulate a strong policy to reach the national goals.

his book provides a comprehensive assessment regarding sociology and welfare development discourses with a new paradigm and approaches to build Indonesian future. his compilation chapter divided into ifteen chapters, conclusion and also given constructive policy recommendations. Although, all authors in this book are depart from various background and issues, yet they produce and extent some challenges should become serious attention especially the government. I can argue that this book is very multidisciplinary and discussed from various angle.

welfare development discourses is smartly promoting the ideas of “spiritual development” which in some extent isolated from main discussion. his is important and also to alerting as well as to underscore that Indonesia is a religious country.

Finally, I am pleased to congratulate to Muhamad Fadhil Nurdin, PhD which successfully publish this book and demonstrated that he is a productive scholar. As academician, lecturer and researcher he has more than thirty years professional experiences in the ield of social and political sciences in Indonesia as well as recognized in the broad. I hope, the collaboration between the agency of research and development in the Ministry of Home Afairs of the Republic Indonesia with the Centre for Socioglobal Studies - Padjadjaran University become more efective, fruitful and sustain in the future.

hank you and Wassalam.

introdUCtion

in the name of god, the most gracioeus, the most merciful

his book provides a thematic issues and challenges in the new era, sociology to develop human welfare. he main objective of the Sociology and Welfare Development is to present an integrated analysis of how the discipline of sociology can contribute to our wider understanding of the variety of welfare development issues, practices and institutions approachs, policies and philosophy wich exist in our society and countries. his explanatory chapters expected to examine and understand as well as ofer choices for human beings in the dinamics world to build a human welfare.

his book depart from the point of view that sociology is as applied social science can contribute to the development of human life through many perspectives. he various theme have been selected are discussed from philosophy to policy models. Each chapter attempt to understand with a core idea namely welfare development.

policy implementation, bureaucracy and corruption. Yet, all indicates that Indonesian government has taken a serious strategic action in order to struggle to eradicate poverty as well as eradication policy against chronic of corruption.Related withpoverty phenomena, in the chapter nine, concern on historical and inherited problems such as the disabled people, the pursuit of full employment in urban areas and overstaing in the public sector, were important causes for urban poverty. However, these historical problems did not result in serious poverty under the well planned economic system. he number of poor people inherited from the previous period was also relatively small.

In the third chapter focus onhuman geography and planning as part of human life. Sociologically, this study concludesthat the relationships between two adjacent metropolitan centres are two geographical phenomena occurred in the Jakarta-Bandung Mega-Urban Region (JBMUR). However, a rapid urbanization process has also been occurring in the corridor area between both metropolitan centers. here are both direct and indirect relations between these two geographical phenomena which inally lead to the emergence of the Jakarta-Bandung mega-urban region. In the fourth chapter, that in addition, the struggle of urban poor communities in Malaysia for housing and land rights is closely related to the development and history of the country. After the British colonial period, Malaysia’s priority was to develop its economy by focusing on the manufacturing and export industry in urban areas. his resulted when people from rural areas migrating from village to the city, in search of opportunities and to ill the workforce demand. Most of the urban migrants would build their own house near the manufacturing factories, because the surrounding lands were unoccupied and unused. With hard work and their own resources they would clean the area (wilderness) and build houses; this would encourage the development in the area and hence they are known as urban pioneers.

obtained inancial assistant from micro LKMS or BMT.

Chapter six examines the environmental destruction of young generation to protect and conserve the natural environment. As such, the key actors in engaging youth participation in environmental action, be it the government, non-governmental organizations (NGO’s) or the community, should address the multi-dimensional issues that are obstacles towards the involvement of the young and come up with strategies to develop a more intrinsically-motivated participation. Generally, environmental awareness among youth worldwide is at an adequate level but it is the translation into action that is still lacking. A review of the implementation strategies of current environmental action programs involving youth should be done by the respective organizers in order to create programs that are fun, hands-on and allows as well as entrusts youth to apply their environmental knowledge and personal skills to make key decisions for the future of then environment which they shall inherit from the present. Hence, there is a need to move beyond the present, traditional top-down institutionalized approach of implementing programs towards a more dynamic and lexible approach in which youth are viewed stakeholders, knowledge sharers and leaders, and not mere passive participants who carry out the aims dictated by the organizers.

rural community towards education as a strategy for improving life. At the same time, the delivery system of the education programs must be enhanced and it is all depend on the commitment of the school and teachers of the rural schools as well.

Finally, the last chapter focus on the incidences of child marriage are no longer pertinent only for less developed country; it actually happens extensively in diferent parts of the world. Due to psychological and biological immaturity, children are insuiciently mature to make an informed decision about a life partner.

his book examines the welfare development issues in the broader “sociology of welfare development” perspective. It is compiled from travelers and knowledge experiences in international seminars, talks and forum of researchers, supervisions and other discussion with my PhD and Master students. hat experiences, together with their personal values and interests extremely inluence to all authors in this book. Personally, I hope that those who engage and read this book will obtain fruitful knowledge. All errors are the author’s responsibility.

Wassalam.

Readers guide

Environmental sustainability is one such key issue that is growing in concern amongst the global youth community. he United Nations, in 2011, has propagated the need for youth to take action on environmental problems via programs or policy-making as environmental de-gradation and resource depletion caused by human activity will exacerbate poverty and inequality levels in the future. his chapter studies investigates the motivating factors for youth to participate in environmental programs as well as challenges and issues which prevent their involvement in such programs. Youth are deined as aged 15 to 18, which is within the United Nations’ deinition of youth. he study reviews the overarching concept of youth participation and

Environmental

Participation among

Youth:

Challenges, issues and motivating

factors

Lim Jen Zen and Muhamad Fadhil Nurdin

Chapter

delves speciically into participation of the young in environmental programs by reviewing cases of successful programs from around the world. he study then identiies and analyses factors which motivate youth participation and citizenship and challenges that prevent their involvement. hese factors and challenges are then related with youth participation in environmental conservation activities from the experiences of case studies from around the world. he indings discuss the three categories of factors which motivate youth based on the Centres of Excellence for Youth Engagement Youth Participation Model, namely self, societal and system as well as issues which afect the intensity of participation of youth in conserving the environment based on a review of existing literature and case studies.

Introduction

Sustainable development has been normally presented as an inter-relation of three components of the ecosystem, namely economy, environment and society, in which the form of progress that takes place has to be one in which each aspect does not compete against each other but reconciles the conlict between social inclusiveness, economic growth and resource protection and conservation (Barton, 2000: 8). In the pursuit for material gains, natural environment have been sacriiced, resulting in a worsening national and global environmental crisis, social problems and institutional breakdowns (Robertson, 1997:14).

sustainable development by stating :

“… the involvement of today’s youth in environmental and development decision-making and in the implementation of programs is critical to the success of Agenda 21…their intellectual contribution and ability to mobilize support… bring unique perspectives that need to be taken into account”1.

Even though they have been much touted as the leaders of today and the future, the low level of youth participation in addressing community and national socio-political issues, including climate change and environmental pollution, and heritage conservation, somewhat dismissed the notion. In the Merdeka Center Youth Survey, conducted over a period of three years between 2006 and 2008, youth self-eicacy is found to be consistently-low, with most youths believing that they have little capability to transform society, despite the contrary depiction of their high level of awareness towards social issues, including protection of the environment. For example, while the environment was the third biggest issue of primary concern towards youth, afecting 16 percent of the respondents in the 2007 Merdeka Center Youth Survey (Merdeka Center, 2007:13), again, youth displayed a lack of self-eicacy in addressing development issues around them, with only 39 percent believing they can solve problems within their respective communities. A total of 21 percent of youth are involved in civic organizations, but half of them were members of political organizations or government-initiated movements such as Belia 4B, Majlis Belia Malaysia or Rakan Muda, with only 5 percent being involved in community level associations (Merdeka Center, 2007:1, 17, 19).

his research paper will seek to address the issue of youth participation in sustainable development programs, particularly on environmental conservation, by exploring the concept of participation and the challenges towards youth participation in general before analysing the issues which have hindered youth from environmental participation and inally, surveying motivating factors of participation amongst the young.

he Meaning of Participation

Before discussing the challenges of youth participation, it is imperative to understand the meaning of participation as viewed from multiple dimensions. First of all, Hart (1992:5) deined participation as

“the process of sharing decisions which afect one’s life and the life of the community in which one lives. It is the means by which a democracy is built and it is a standard against which democracies should be measured. Participation is the fundamental right of citizenship”.

However, Hart’s deinition can be perceived as being too wide. Midleton (2006) in his deinition narrowed down youth participation as “giving children and young people (usually up to the age of 18) a chance to express their views on aspects of life that afect them”. More speciically, homas and Percy-Smith (2010) deined youth participation as a complex concept which involves active participation and decision making by the young at diferent levels ranging from everyday events to speciic incidences. hey also speciied participation as a foundation for the practice of citizenship. In a review of 14 diferent meanings of youth participation, Farthing (2012) discovered that ten of the deinitions described participation as involving decision making while seven deinitions limited the process towards issues which afect the young. Four of the deinitions postulated the notion of “active involvement”. Hence, it can be summed up that youth participation is the active engagement of the young to take action on, including making decisions, on issues that afect them. As the future leaders, environmental sustainability is certainly an agenda which will leave a huge impact towards their lives and one which they need to take pertinent action on.

from consultation, training, one-of events or projects to governance. Participants sampled are not limited to merely the leaders, but will also encompass other levels of involvement such as advisor, being part of a committee as well as ordinary membership. Nevertheless, these concepts are still endured to the concept of sustainable development. Nurse (2006) the three pillars of sustainable development are showed as below graph.

Based on the Nurse’s guide the following sections will explore more about the concept of participation on regards youth participation.

he Challenge of Youth Participation

“No one is born a good citizen; no nation is born a democracy. Rather both are processes that evolve over a lifetime. Young people must be included from birth. A nation that cuts itself from its youth severs its lifeline”

- Koi Annan (in Ragan & McNulty, 2004:28)

his bold statement by the former Secretary General to the United Nations’ accentuated the importance of youth as civic actors of a nation. Even though the world population is nearing the last stage of its demographic transition with the number of 15 to 24 year olds 2

declining, the number of youths in this age group is booming in the developing regions of the Middle East, South and Southeast Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa. Approximately 90 percent of world youth live in developing nations (ILO, 2010:7) where the efects of environmental degradation are strongly felt compared with developed countries as a result of development pressures, resource limitations and weak national as well as international political commitment and governance (O’ Connor & Turnham, 1992). With the youth population in Africa and South Asia continuing to increase exponentially between the year 2010 and 2015 (ILO, 2010:7), they are a strong force for civic engagement which can assert their inluence and lead eforts towards safeguarding their natural resources for the long-term. Being next in line to lead their communities, the present youth cohort worldwide must develop their civic eicacy, leadership capacity and worldview to face the challenges of globalization and sustainability which they will carry upon their shoulders.

Despite the emerging pertinence of youth civic participation, the capability and efectiveness of youth as civic actors’ remains contested. heir lack of interest towards public afairs has cast a negative light on their much espoused role as future leaders. A cross-cutting study by the International Education Agency on civic engagement among 14 year-olds in 28 countries highlighted their moderate interest towards politics and is not interested in any forms of civic-related activities such as becoming organization members, petitioning or running for public oices (Torney-Purta et.al., 2001). Empirical studies in developed nations such as America (Putnam, 2000; Carprini, 2000.), Canada (Stolle & Cruz (in Government of Canada, 2005:82-97)) and Spain (Blanch (in Forbrig (ed.), 2005:63-5)) showed declining civic engagement levels among youth. he consumerist-oriented society which eschewed collectivity for individualization has been blamed for shaping cynicism and disengagement among urban youth in developed nations (Beck & Beck-Gernsheim (in Wood, 2010)).

of the respondents have little or no conidence in youths assuming civic leadership. Such general assumptions of young adulthood as a period marked by “heightened storm and stress” (Arnett, 1999) are adversative towards civic democracy, especially in the realm of environmental action.

Declining civic engagement among youth, however, is not simplistically caused by the inluence of communal social capital alone. Holland, Reynolds and Weller (in Hastings et.al., 2011) suggested youth can develop their own social capital via new ways of engagement. He theorized that it is more diicult to mobilize a group following their inclusion into democratic politics via institutions as compared to before their inclusion. Institutionalization has created a dependency between the public and the institutions, in which the general public perceived and left issues to be handled by the political institutions. At the same time, bureaucratization and monopolization of community issue by the institutions has also limited the involvement of the public in addressing matters pertaining to their living environment.

Youth Participation in Environmental Programs

An abundance of international literature has highlighted the role of youth in community development as well as how citizen groups, governments and non-proit as well as non-governmental organizations are providing opportunities to support it. Dodd (in Chawla, 2002) acknowledged the growing global recognition of youth as a nascent force in the development process, as how women are after the emergence of the women’s rights movement, stating that: “Listening to smaller voices, by which children are brought into the process of planning, implementation and evaluation of endeavours undertaken in the interests of the whole community, means embracing the interlinked concepts of gender and generation” (Dodd (in Chawla, 2002)).

is to create a sustainable living environment. Rapid physical development spurred on by exponential economic growth in the world, and has simultaneously resulted in the destruction of our natural environment. Pollution and climate change has become pressing problems that will create disastrous efects on the lives of the future generation, leading to food shortages, lack of clean water, polluted atmosphere which will only result in them being vulnerable to malnutrition and illness (United Nations, 2010:1).

Existing experiences of youth involvement in environmental protection, be it in decision making or action, adult-supported or youth initiated, have proven their viability as a force that adds value to the process for sustainable change. National and local governments, intergovernmental agencies such as the UN and World Bank, as well as the corporate sector and NGO’s are leveraging on youth as valuable knowledge and skill resources, and have formed cohesive partnerships with them to embark on new opportunities to further the agenda of environmental conservation such as social and eco-based enterprise, watchdog groups and community advisory roundtables (World Bank, 2006).

Issues of Youth Participation in Environmental Programs

years. Most youth were also found to be apathetic towards encouraging pro-environmental behavior among their peers for fearing it will disrupt ties among peers and being viewed as busybodies. It is also found that youth are generally inactive in participating in environmental programs due to a lack of concern and knowledge of such activities, as well as a pessimistic view that their simple actions would not make an impact towards environmental conservation (Abdul Latif Ahmad, 2012).

he results of Abdul Latif ’s research were concurrent with that of Aini M.S., Nurizan Y. & Fakh’rul-Razi A. (2007), which indicated a low level of participation in environmental action among secondary school students aged between 15 and 17 in Johor Bahru. While an overwhelming majority of 93 percent of the students were aware of environmental issues, such as forest destruction, indiscriminate toxic disposal and ozone depletion, the level of participation in environmental activities such as campaigns, nature clubs and community work is rather low, with only 6 percent having been a member of nature organizations such as World Wildlife Fund (WWF), Friends of the Earth and Nature Lovers’ Club. Likewise, a study conducted by Othman et.al. (2004) on environmental consumer practices among secondary schooling youth in Klang Valley, Malacca and Sarawak also indicated low levels of commitment among the young to improve their environment.

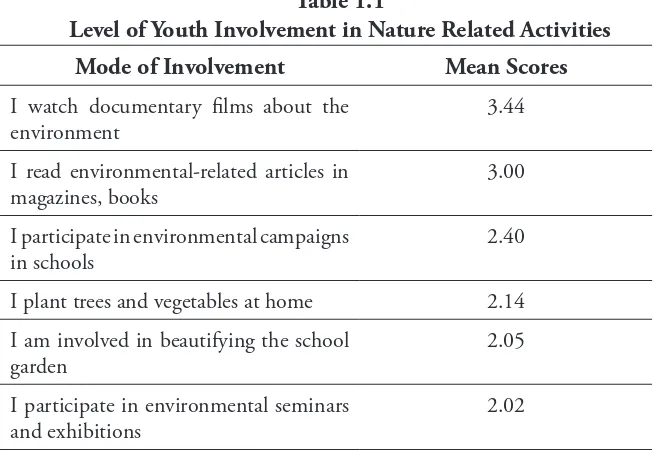

Table 1.1

Level of Youth Involvement in Nature Related Activities

Mode of Involvement Mean Scores

I watch documentary ilms about the environment

3.44

I read environmental-related articles in magazines, books

3.00

I participate in environmental campaigns in schools

2.40

I plant trees and vegetables at home 2.14

I am involved in beautifying the school garden

2.05

I participate in environmental seminars and exhibitions

I surf the net for environmental

Source: Aini M.S., Nurizan Y. & Fakh’rul-Razi A. (2007)

Similarly, in Scotland, a survey of youths aged 16 to 24 has in 2000 has found that the consideration of environmental problems as a pertinent issue is lesser amongst people from this age cohort. Negative perception from adults, a political system which alienated youth and do not hear their voices and a lack of information about participation opportunities have appeared to be the reason behind this apathy in taking action on environmental problems. Many youth are succumbed to social pressures, such as attaining popularity, excelling in examinations and being good at sports while viewing civic involvement as “uncool”. he duration of a program is also impactful towards sustained youth involvement in protecting their environment. A large number of programs are of a short-term basis and youth who are only involved in environmental programs for a short duration of less than 18 weeks usually demonstrate a lack of interest and will drop out of such programs (Schusler & Krasny, n.d.).

a centre or organization which carries out environmental action in their neighborhood may become a hindrance towards further involvement in environmental work. Responsibility refers to whether a program has direct impact towards youth. he young are not keen on programs which are conducted by people or authorities which they do not trust. hey believe that governments do not listen to them and would not take authoritative action on any of the environmental problems they have raised (Abdul Latif Ahmad, 2012).

Factors Motivating Youth Participation in Environmental

Programs

As the threat of rapid physical progress began to impinge on the sustainability of the natural environment of a city, there is a growing need for the young to assume the mantle of leaders who spearhead initiatives and invigorate community awareness on the importance to take accountability for the conservation of our limited resources. If judged by the sheer size of the global youth population, they constitute a strong base of human capital that is major stakeholders in the development of their communities. he United Nations (2010:6) has presented granting youth participation in development as an investment which strengthens their ability to meet their own needs, reduces their vulnerability to economic, political and social instabilities, promotes sustainability of development strategies and facilitates entry into target groups as well as builds social capital.

Studies on youth participation in environmental action view the factors motivating involvement in protection of the environment mainly from two viewpoints, namely their formative experiences and contemporary factors (Chawla & Cushing, 2007).

Prior Formative Experiences in Environmental Action

have been criticized for being retrospective without taking into account contemporary experiences (Scott (in Chawla & Cushing, 2007)), it has to be noted that the relevance of past experiences have been a pertinent factor towards driving youth and adult participation in the environment, as evident through similar indings in studies on youth participation in the environment (Wells & Lekies, 2006; Sia, Hungerford & Tomera, 1986).

Contemporary Factors

Besides childhood experiences, the decision of a youth to take active part in environmental protection has also been attributed to several contemporary factors which may impact levels of participation, such as gender, socioeconomic levels and environmental knowledge (Chawla & Cushing, 2007). Women might possess less knowledge of the environment but are more emotionally concerned about its destruction compared to men (Roper Starch Worldwide, 1999). People of lower income groups tend to participate in ecological protection-related actions only if it beneited them economically (Roper Starch Worldwide, 1994).

he Role of Internal and External Factors in Motivating

Participation

he decision of youths to engage, or not, in an environmental action initiative is also inspired by circumstances from both external and internal factors. Studies regarding youth engagement in ields connected to sustainability, such as environmental awareness and conservation, rural and urban community development, politics and volunteer work, have suggested a multiplicity of factors, both internal and external, which promoted the involvement of the younger generation, such as incentives (Collins, Bronte-Tinkew & Burkhauser, 2008), peer inluence (Brander & Rivera-Caudill, 2008; Cano & Bankston, 1992), government policies (Etra et.al., 2010:7) and demographic predictors such as ethnicity, gender, household income and level of education (Borden et.al., 2006; Fahmy, 2004).

External Factors

Source: Ryan and Deci (2000), adapted.

Use of incentives

he use of incentives to attract youth to participate in a civic program might sustain their interest and participation, thus indirectly forming their sense of ownership towards the program. Continuous participation as an indirect result from the motivation of incentives could also strengthen the learning culture among the youth participants, which can spur academic achievements in schools or higher learning institutions (Collins, Bronte-Tinkew & Birkhauser, 2008). Incentives ofered to youth participants in a community engagement program may range from inancial incentives, food, prizes and ield trips (Collins, Bronte-Tinkew & Birkhauser, 2008). Ofering monetary incentives have been found efective in motivating youth, especially teenagers, to be engaged in a civic project (Institute of Educational Sciences (in Collins, Bronte-Tinkew & Birkhauser, 2008)). It also played a role in ensuring their engagement in a particular project is sustained (Arbreton, Shelton & Herrera, 2005:21).

familial Support and Socioeconomic background

Parents who are warm and supportive of their children’s involvement, via caring, listening and getting them to join activities, tend to enhance their enjoyment and ability to experience the beneits from an extra-curricular activity, whereas parents who pressure their children to participate, by limiting their participation to selected activities, placing high expectations on them and being disappointed at their failures, only serve to lower their enjoyment of the activity. studies on role of families in the process of civic and political socialization have also uncovered a signiicant link between youth participation and family socioeconomic status, in which youngsters who recorded strong intention to be involved in community development, civic and political programs as well as co-curricular activities tended to have originated from families with high level of parental education (Ng, Ho & Ho, 2009; McIntosh, Hart & Youniss, 1997 and income (Foster-Bey, 2008; Lerner et.al., 2005). Ng, Ho, Ho (2009) attributed a more robust civic engagement among middle and upper class youth compared to those from the working class to diferences in family socialization as well upbringing between the classes. Children from families in the middle and upper class tend to have lesser worries on inancial and basic needs, would have more time, space and motivation to engage in extra-mural activities. hese activities would deine their identities and aspirations which are broader and higher than those of working class children. Working class children, meanwhile are more focused on making ends meet, which is a more important motivation than the potential beneits acquired from co-curricular and civic engagement (Ng, Ho & Ho, 2009).

Peer inluence

In the realm of youth civic and community participation in the environment, peer inluence has also been found as a signiicant predictor for a youth’s decision to engage voluntarily in improving their living communities. Brander & Rivera-Caudill (2008) studied the factors predicting participation of youth in the Michigan Youth Farm Stand Project, which is targeted at youth from lower-income urban communities to establish food systems and catalyze economic development. From their in-depth interviews with participants, it is gleaned that peers are a motivator for participation among these members. Participants came on board the project either due to the involvement or interest shown by classmates and close friends, or to develop new relationships with fellow peers. he study on youth participation in Michigan highlighted that prosocial peers are a key element in instilling responsibility towards the community among youth. Similarly, Cano & Bankston (1992) in their study on participation or non-participation among ethnic minority youth in 4-H programs in Ohio also yielded that participants are motivated to volunteer because “their friends were in the program”, as well as to “make new friends”. Peer socialization, as seen from the outcomes of studies above, can serve as both a push or pull factor for youths to embrace citizenship and community engagement, which could spur a more intense involvement in addressing community issues, including those pertaining to sustainability.

education System

environmental surveys, as evident in a study by Schusler & Krasny (n.d.) on the levels of participation among youth in the Garden Mosaics project in Sacremento, California.

On the other hand, the school system itself might also motivate, or coerce, students into participating in environmental action. An authoritarian school culture which enforces the notion of keeping the school clean might drive young people to carry out various projects or activities to keep the school environment clean. However, as Silo (2011) noted in her study on child participation in waste management activities in Botswana, participation in such context are not meaningful and the participants do not respond well to participate in the waste management programs organized by the school. However, following the implementation of open dialogue between teachers and students, a sense of enjoyment and ownership towards the environmental activities started to develop among the children as their ideas are now being respected. Likewise, Arnold, Cohen & Warner (2009) also noted that youth whose schools encouraged outdoor activity and environmental action beyond the classroom are more inclined to become involved in environmental action in their wider community. Hence, it can be deduced that schools which adopt a participatory structure and allow youth to initiate their own environmental action program in the wider community are more likely to inculcate a stronger sense of environmental responsibility among its students.

Internal Factors

been postulated as extrinsically-motivated, Hidi & Harackiewicz (in Pearce & Larson, 2006) contended that the impact of rewards towards the participant depended on the length and intricateness of the activity and combining intrinsic rewards, in the form of interesting activities, and external rewards, such as gifts and feedback, are necessary to ensure the sustainability of engagement in a diicult activity or learning process. Youth who are intrinsically motivated to participate in environmental action would also derive greater satisfaction from the outcome of their actions and tend to adopt environmental conservation in their everyday behaviour (De Young, 1985).

Discussion

In this survey of key issues and challenges as well as motivating factors towards youth environmental participation, it is found that the driving forces and hindering problems towards the engagement of youth are multi-faceted. he lack of interest among youth in civic engagement as well as traditional forms of engagement via institutions, which more often than not stile the views of youth, has posed a challenge towards youth access into participation in the wider community. he individualist attitudinal orientation of modern society causes a lack of collectivism among youth when it comes to civic action. Disinterest from public institutions that are involved in environmental action to include youth in their decision making process could lead to a lack of consideration on the needs of the younger generation in safeguarding the future of their environment. Negative opinions and intolerance from adults, who view youth as a threat rather than an asset towards environmental decision making, and the lack of trust ofered by them towards the younger generation also hamper further involvement of the young in addressing issues within their living community (Camino & Zeldin, 2002).

youth involvement, conirming Blake’s (1999) analysis of individuality, practicality and responsibility as key barriers towards participation . Apathy and laziness as well as the lack of conidence that youth can change the world have been oft cited as reasons why youth do not actively participate in environmental work (Abdul Latif Ahmad, 2012). he fact that youth have to juggle multiple commitments of school, family and even work means that involvement in environmental action becomes less practical and more often than not becomes less important in their list of priorities.

he general mistrust of youth towards government institutions have also caused them not to take any environmental action as they believe their actions will be inconsequential and the authorities will not use their authority to solve any environmental problem (Abdul Latif Ahmad, 2012). his is a pressing concern for governments and they need to now look at increasing awareness among the young on key environmental policies as well as to provide platforms for youth to engage with them in making key decisions about the environment, be it through sustained nationwide environmental programs at school level, the setting up of a decision making body which consist of youth or even the use of social media as forums of discussion and decision making. he government needs to make environmental action relevant and “cool” for the younger set as well as to allow them the opportunity to take ownership of their actions.

However, surveying factors of participation from the perspective of motivation gives a clearer picture as to the reasons behind the involvement of the young in the cause of environmentalism. Extrinsic factors such as use of incentives, family socioeconomic background, peer inluence as well as the education system may afect decisions to participate or not. Concurring with the results of a similar study by Perkins et. al. (2007) on factors behind the participation or non-participation of minority youth in structured programs, youth from poor familial socioeconomic backgrounds will place educational and economic priorities above other activities. At the same time, they may not be as highly exposed and aware of environmental problems as those with better-educated and higher income parents. Hence, this discovery presses for the need for governments to integrate elements of entrepreneurship into environmental action programs when targeting youth from disadvantaged families. Meanwhile, the encouragement from friends or the motive of making new friends has also been a consistent motivator for participation (Ferrari & Turner, 2006; Brander & Rivera-Caudill, 2008). his suggests the importance of environmental programs as a platform for building strong and cohesive social networks which may in turn build dynamic environmental action movements in the future. A school learning environment or education system, which encourages experiential-based learning, can foster enthusiasm and interest for youth to persist in their involvement with nature. However, mandated involvement may result in initial reluctance among youth to be involved in the programs (Pearce & Larson, 2006). Ryan and Deci (2000) postulated in their Self-Determination heory that motivation for participation can be viewed in a continuum from a motivation through intrinsic motivation, with increasing motivation moving from the former to the latter. Involvement that is done by request of others is considered as a motivation. However, continuous involvement and engagement in an environmental project will eventually develop a sense of enjoyment and satisfaction among the youth participants, meaning that the reason for their sustained involvement is no longer because they were mandated to participate (Brander & Rivera-Caudill, 2008). Youth who are intrinsically-motivated tend to eventually adopt pro-environmental behavior in their lives.

of internally-motivated participation is when the challenges are personally challenging for the participant itself. Hence, environmental programs should connect their causes with the personal goals of its participants and allow them to develop skills that allow them to meet these challenges. his would then compel them to continue their engagement in a program and develop higher level skills to meet more advanced challenges (Pearce and Larson, 2006).

Conclusion

he growing concern of environmental destruction means that the involvement of the younger generation of today to protect and conserve the natural environment is imperative. As such, the key actors in engaging youth participation in environmental action, be it the government, non-governmental organizations (NGO’s) or the community, should address the multi-dimensional issues that are obstacles towards the involvement of the young and come up with strategies to develop a more intrinsically-motivated participation. Generally, environmental awareness among youth worldwide is at an adequate level but it is the translation into action that is still lacking. A review of the implementation strategies of current environmental action programs involving youth should be done by the respective organizers in order to create programs that are fun, hands-on and allows as well as entrusts youth to apply their envirhands-onmental knowledge and personal skills to make key decisions for the future of then environment which they shall inherit from the present. Hence, there is a need to move beyond the present, traditional top-down institutionalized approach of implementing programs towards a more dynamic and lexible approach in which youth are viewed stakeholders, knowledge sharers and leaders, and not mere passive participants who carry out the aims dictated by the organizers.

entrepreneurship (e.g. a recycling business). Organizers of environmental programs have to still recognize that the power of peer inluence remains a strong motivating factor of involvement. While the level of motivation by peers is closer to a motivation than intrinsic motivation in the Self-Determination heory, youth, especially those in their adolescence, tend to follow the actions of their peers and are easily swayed by the encouragement of friends of a similar age who are leaders or initiators of an environmental program.

Overall, the issues and motivating factors surveyed in this article is not by all means exhaustive and future studies should be carried out to determine if there are certain types of environmental action programs which may be more attractive to youth compared to others. Also, investigation should also be made on the impact of culture or ethnicity towards environmental action participation.

References

Abdul Latif Ahmad. (2012). he Understanding of Environmental Citizenship

among Malaysian Youths: A Study on Perception and Participation. Asian Social Science, 8(5): 85-92.

Aini M.S., Nurizan Y. & Fakh’rul-Razi A. (2007). Environmental Comprehension and Participation among Malaysian Secondary School Students. Environmental Education Research, 13(1), 17-31

Anderson, J.C. et.al. (2003). Parental support and pressure and children’s extracurricular activities: Relationships with amount of involvement and afective experience of Participation. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 24(2), 241-57.

Arbreton, A.J., Sheldon, J. & Herrera, C. (2005). Beyond safe havens: A synthesis of 20 years of research on Boys and Girls Clubs. Philadelphia: Public/Private Ventures.

Psychologist, 54(5), 317-26

Arnold, H., Cohen, F & Warner, A. (2009). Youth and environmental action: Perspectives of young environmental leaders on their formative inluences. Journal of Environmental Education. 40 (3). 27-36.

Barton, H. (2000). Sustainable communities: he potential for eco-neighbourhoods. Oxon: Earthscan.

Borden, L.M. et.al. (2006). Challenges and Opportunities to Latino Youth

Development-Increasing Meaningful Participation in Youth Development Programs. Hispanic Journal of Behavioural Sciences, 28(2), 187-208.

Blake, J. (1999). Overcoming the value-action gap in environmental policy:

tensions between national policy and local experience. Local Environment, 4(3), 257-278. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/ 13549839908725599

Brander, A.A. (2008). Factors inluencing participation motivation and engagement in the Michigan Youth Farm Stand Project. East Lansing: Michigan State University.

Brander, A.A. & Rivera-Caudill, J. (2008). Michigan Youth Farm Stand Project: Facets of participant motivation. Journal of Career and Technical

Education, 24(2), 42-56.

Camino, L. & Zeldin S.(2002). From periphery to center: Pathways for youth civic engagement in the day-to-day life of communities. Applied Developmental Science, 6(4), 213-20.

Cano, J. & Bankston, J. (1992). Factors which inluence participation and non-participation of ethnic minority youth in Ohio 4-H programs. Journal of Agricultural Education, 33(1), 23-9.

Carprini, M.X.D. (2000). Gen.com: Youth, civic engagement and the new

Chawla, L. (2002). Insight, creativity and thoughts on the environment: Integrating children and youth into Human Settlement Development. Environment and Urbanization, 14(2), 11-22.

Chawla, L. (2007). Childhood experiences associated with care for the natural world: A theoretical framework for empirical results. Youth and Environments, 17(4), 144-70.

Chawla, L. & Cushing, D.F. (2007) Education for strategic environmental behavior, Environmental Education Research, 13(4), 437-452

Collins, A., Bronte-Tinkew, J. & Birkhauser, M. (2008). Using incentives to

increase participation in out- of- school-time programs. Retrieved 21 September 2012 from http://www.nccap.net/media/pages/ Child_Trends-2008_06_18_PI_OSTIncentives.pdf

Csikzentmihalyi, M. (1990). Flow: he psychology of optimal experience. New York: Harper and Row

De Young, R. (1985). Encouraging environmentally appropriate behavior:

he role of intrinsic motivation. Journal of Environmental Systems, 15(4), 281-92.

Etra, A. et.al. (2010). Youth development through civic engagement – Mapping assets in South Asia. Retrieved 18 September 2012 from

http://pravahstreaming.iles.wordpress. com/2011/02/youth-development-through-civic-engagement-in-south-asia.pdf.

Fahmy, E. (2004). Youth, social capital and civic engagement in Britain. Evidence from the 2000/01 General Household Survey. ESRC/ODPM Postgraduate Research Programme Working Paper 4.

Farthing, R. (2012). Why Youth Participation? Some Justiications and Critiques of Youth Participation Using New Labour’s Youth Policies as a

Ferrari, T.M. & Turner, C.L. (2006). An exploratory study of adolescents’ motivations for joining and continued participation in a 4-H afterschool program. Journal of Extension, 44(4). Retrieved 16 September 2014 from http://www.joe.org/joe/2006august/rb3p. shtml

Forbrig J., éd. (2005). Revisiting Youth political participation. Strasbourg: Council of Europe.

Foster-Bey, J. (2008). Do race, ethnicity, citizenship and socio-economic status determine civic-engagement? CIRCLE Working Paper no. 62.

Retrieved 25 September 2012 from http://www.civicyouth.org/ PopUps/

WorkingPapers/WP-62/Foster.Bey.pdf

Griin, C. (1997). Troubled Teens: Managing Disorders of Transition and Consumption. Feminist Review, 55, 4-21.

Hart, R. (1992) Children’s Participation: From Tokenism to Citizenship, Florence: Unicef Innocenti.

Hastings, L.J. et.al. (2011). Developing a Paradigm Model of Youth Leadership Development and Community Engagement: A Grounded heory. Journal of Agricultural Education, 52(1), 19-29.

International Labour Organization. (2010). Global employment trends for youth. Geneva: ILO

Jensen, B.B. (2002). Knowledge, action and pro-environmental behaviour.

Environmental Education Research, 8(3), 325-34.

Kempton, J. et.al. (1995). Environmental values in American culture. Cambridge: MIT Press

Kuhlmeier, H., Van den Bergh, H. , Lagerweij, N. (1995). Environmental

Lerner, R.M. et.al. (2005). Positive youth development, participation in community youth development programs, and community contributions of Fifth-Grade adolescents: Findings from the irst wave of the 4-H study of positive youth development. Journal of Early Adolescence, 25(1), 17-71.

O’Connor, D. & Turnham, D. (1992). Managing the Environment in Developing Countries. Policy Brief No.2, Paris: OECD Development Centre.

Othman, M.N. et.al. (2004). Environmental Attitudes and Knowledge of Teenage Consumers. Malaysian Journal of Consumer and Family Economics, 7: 66-78.

Merdeka Center. (2007). he Merdeka Center Youth Survey 2007. Kuala Lumpur: Merdeka Center.

Midleton, E. (2006) ‘Youth Participation in the UK: Bureaucratic Disaster or Triumph of Child Rights?’ Children, Youth and Environments 16 (2) pp. 180 – 190.

Ng, I.Y.H., Ho, K.W., & Ho, K.C. (2009). Family environment, class, and youth social participation. YouthSCOPE, 3, 78-90.

Noraini Jaafar. (1992). Sustainable development in perspective. Deinitions, concepts and policy issues. Working Paper.

Nurse, Keith (2006), Culture as the Fourth Pillar of Sustainable Development, Institute of International Relations, University of the West Indies, Trinidad and Tobago, June.

Pearce, N.J. & Larson, R.W. (2006). How teens become engaged in youth development programs: he process of motivational change in a civic activism organization. Applied Developmental Science, 10(3), 121-31.

participate. Youth and Society, 38(4), 420-42.

Peteru, P. (2006). Youth participation in local councils in the Auckland Region. Auckland: VDM Verlag.

Putnam, R.D. (2000). Bowling alone: he collapse and Revival of American Community. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Ragan, D. & McNulty, L. (2004). Child and youth friendly cities. Vancouver: Environmental Youth Alliance, International Institute of Child Rights and Development.

Ryan, R.M. & Connell J.P. (1989). Perceived locus of causality and internalization: Examining reasons for acting in two domains. Journal of

Personality and Social Psychology, 57, 749–761.

Ryan, R.M. & Deci, E.L. (2000). Self-determination heory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development & well-being.

American Psychologist, 55(1), 68-78.

Samsulkamal Sumiri. (2008). Public participation of sustainable

development: Investigation of the level of sustainable development understanding and awareness. Johor: Universiti Teknologi Malaysia.

Sarkar, M. (2011). Secondary students’ environmental attitudes: he case of environmental education in Bangladesh. International Journal of

Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 1, 107-16.

Schusler, T. & Krasny, M.E. (n.d.). Youth participation in local environmental action: Integrating science and civic action. Retrieved 10 October 2014 from http://communitygardennews.org/ gardenmosaics / pgs/aboutus/materials/Youth_Participation.pdf

Silo, N. (2011). Children’s participation in waste management activities as

a place-based approach to environmental education. Children, Youth and Environments, 21(1), 128-48.

Participation: perspectives from theory and practice. London: Routledge

Torney-Purta, J. (2001). Citizenship and education in twenty-eight countries: Civic knowledge and engagement at age fourteen. Amsterdam: IEA.

Robertson, J. (1999). he new economics of sustainable development: A brieing for policy makers. New York: Kogan.

Roper Starch Worldwide. (1999). Roper Report: National Environmental

Education Foundation. Retrieved 3 September 2012 from http://www.neefusa.org/pdf/roper/99reportcard.pdf

Sia, A. P., Hungerford, H. R., & Tomera, A. N. (1986). Selected predictors of

responsible environmental behavior: An analysis. Journal of Environmental Education, 17(2), 31-40.

United Nations. (2010). Sustainable development: From Brundtland to Rio

2012. New York: United Nations.

United Nations. (n.d.). Children and youth in sustainable development. Retrieved 8 February 2011 from http://www.unep.org/Documents. Multilingual/Default.Print.asp? documentid=52&articleid=73

Wells, N. M., & Lekies, K. S. (2006). “Nature and the life course: Pathways

from childhood nature experiences to adult environmentalism.” Children, Youth and Environments, 16(1).

World Bank. (2006). Youth responsive social analysis: A guidance note. Washington DC: World Bank.