Contextualizing Cultural Orientation and Organizational

Citizenship Behavior

Charlotte M. Karam

a,⁎

, Catherine T. Kwantes

ba

Olayan School of Business, American University of Beirut, 110236, Riad El Solh, Beirut 11072020, Lebanon bDepartment of Psychology, University of Windsor, 401 Sunset Avenue, Chrysler Hall South 257

–3, Windsor, Ontario, Canada N9B 3P4

a r t i c l e

i n f o

a b s t r a c t

Article history:

Received 19 February 2011

Received in revised form 14 April 2011 Accepted 3 May 2011

Available online 26 May 2011

This research attempts a more contextualized approach to examining organizational citizenship behavior (OCB). Borrowing from theory in international and cross cultural management as well as organizational behavior, context is conceptualized as multi-level and as a shaper of meaning and variability in employee citizenship behaviors. By centralizing the unique socio-cultural, political and historical national context (i.e., omnibus context) of Lebanon at the core of our theorizing, we hypothesize, contrary to previous research, a positive relationship between idiocentrism and employee engagement in organizational citizenship behaviors. Furthermore, we explore the influence that unit level OCB (i.e., discrete context) has on the idiocentrism–OCB relationship. Our analysis confirms the positive relationship between idiocentrism and OCB in this unique context. In addition, our cross-level analysis suggests that in workgroups with higher levels of unit level OCB, idiocentrism is more strongly related to employee engagement in OCB. The findings highlight the value added in contextualizing research on OCB and employee behavior in general.

© 2011 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. Keywords:

Unit level OCB OCB Cultural values Idiocentrism Allocentrism Lebanon

1. Introduction

There has been a growing interest in contextualizing research on employee behavior (Rousseau and Fried, 2001). This is of particular importance in thefield of international management as it is becoming more and more apparent that as workplaces become more global and as MNCs function in a greater variety of geographical locations, a change in context or contextual variables can have profound effects on the meaning and manifestation of employee behaviors, such as Organizational Citizenship Behavior —OCB (Paine and Organ, 2000). Understanding OCB in an international arena requires an understanding of what contextual variables are important as determinants of workplace perceptions and behaviors, as well as understanding the extent to which theories developed in one specific context may be applicable to other contexts. Without examination, it would be premature to assume that OCB models and theories developed in the West can be directly applied to contexts outside the West. Rather, for such knowledge to contribute to international management it must be empirically examined in, and possibly adapted for, a variety of cultural contexts and a variety of workplace settings. Such efforts are indispensable for the generation of a solid body of management theory that is truly international and valuable in its day-to-day application.

In this paper we focus on a more contextualized examination of the antecedents of organizational citizenship behavior (e.g.,

Ehrhart and Naumann, 2004; Fischer et al., 2005), specifically recognizing that engagement in OCB is strongly affected by the context within which an employee works. Consider the case of Maya who decides tofill in for a colleague at work. If Maya works in a cultural context where the expectations for helping others are salient, or in a department where it is quite the norm to engage in OCB, her behavior is likely to be perceived as less praiseworthy than when doing so is unexpected or unusual. Considering context makes our interpretations more accurate (Schneider, 1985) and our understanding of OCB more informed.

⁎Corresponding author. Tel.: + 961 1 350 000x3764 (office); fax: +961 1 750 214.

E-mail addresses:[email protected](C.M. Karam),[email protected](C.T. Kwantes). 1075-4253/$–see front matter © 2011 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.intman.2011.05.007

Contents lists available atScienceDirect

Organizational citizenship behaviors are behaviors that support the broader organizational, social, and psychological environment in which employees work (Borman and Motowidlo, 1993; Organ, 1997). These behaviors tend to be perceived as extra-role and tend not to lead to formal organizational rewards (Organ, 1997). The demonstrated positive relationship between OCB and productivity at both the employee and organizational levels (Dunlop and Lee, 2004; Koys, 2001; Podsakoff et al., 2000; Podsakoff and Mackenzie, 1994; Podsakoff and Mackenzie, 1994) has catapulted it to top research topic status. To capitalize on this positive and important link, many have turned their research attention to the potential antecedents of OCB (for reviews see

Podsakoff et al., 2000; Van Dyne et al., 1995). The antecedent of particular interest for the current study is an employee's cultural values (Triandis, 1989, 1996) and more specifically his/her allocentric and idiocentric orientations.

Allocentrism and idiocentrism have each been conceptualized as separate but related individual difference constructs (Triandis, 1989). Allocentrism, on the one hand, can be defined as an individual's cultural value orientation towards viewing the self as inseparable from other ingroup members (Triandis, 1989). Idiocentrism, on the other hand, is an orientation towards viewing the self as separable from others (Triandis, 1989). Taking these cultural values as well as contextual considerations into account, our general research question is:How does context influence the relationship between an employee's cultural values (i.e., allocentrism and idiocentrism) and his/her engagement in OCB. More specifically, our research focuses on two types of contexts, asking:To what extent does the larger societal culture affect this relationship?and To what extent does the context within the organization (i.e., the perceived behavioral norms) affect this relationship?

To begin to answer these questions we borrow from the work ofJohns (2006)who defined context in terms of situational opportunities and constraints and who identified two important levels of context for organizational research:Omnibusand Discrete. On the one hand, we conceptualize omnibus context as the environment broadly defined—the socio-cultural, political and historical environment that characterizes a nation. Our aim is to select an omnibus context that is unique when compared to previous OCB research environments, thus contributing to the body of international management research by contextualizing and extending previous findings. We choose to focus our research within Lebanon and hope to theoretically suggest how its uniqueness may influence the meaning, manifestation, and certain nomological relationships of OCB.

Discretecontext, on the other hand, refers here to specific unit level behavioral characteristics within the organizational setting; such as, unit level OCB (Ehrhart, 2004; Ehrhart and Naumann, 2004). Theorized in this way, unit level OCB may serve as a contextual variable that moderates the relationship between an employee's allocentric and idiocentric values and his/her level of OCB. Based on this therefore we approach our research question by examining descriptively how the omnibus environment may shape (1) the relationship between cultural values (i.e., allocentrism and idiocentrism) and employee engagement in OCB as well as (2) the cross level relationship between discrete context (unit level OCB), cultural values (i.e., allocentrism and idiocentrism), and OCB.

1.1. Review of the literature

1.1.1. The central relationship of interest: an employee's cultural values and OCB

If we examine the nomological network of OCB, we note that there are a number of individual difference antecedents that researchers have examined (Van Dyne et al., 2000). However, a close look at these antecedents reveals that research linking culture as an individual difference variable to OCB have not been frequently explored. There are however some exceptions. For example, a few studies have examined the relationship between an individual's cultural beliefs (Ersoy et al., 2010) or an individual's cultural values (Moorman and Blakely, 1995; Ramamoorthy and Flood, 2004; Van Dyne et al., 2000) and OCB. Cultural values (Triandis, 1989) are linked conceptually to the work of Hofstede (1984) on collectivism and individualism. More specifically, the terms allocentrism and idiocentrism were coined byTriandis (1989)to represent the individual level conceptualization of Hofstede's nation level constructs.

As separate but related individual difference constructs, allocentrism and idiocentrism are useful in capturing a person's cultural value orientation (Triandis, 1989). Allocentrism, on the one hand, can be defined as an individual's cultural orientation towards viewing the self as inseparable from other ingroup members (Triandis, 1989). Allocentrics have a tendency to (1) have personal goals that are compatible with ingroup goals; (2) emphasize norms, duties, and obligations when making decisions about how to behave or act; and (3) give priority to relationships and the needs of other ingroup members even at the expense of their own needs (Triandis and Bhawuk, 1997, p. 15). If allocentrics tend to emphasize ingroup goals and give priority to ingroup member needs, then it is likely that they will engage in behaviors that support and aid coworkers. Allocentrics will likely engage in this behavior even if it is not an in-role requirement and not formally rewarded. Such behaviors clearly fall within the content domain of OCB. Peer-reviewed empirical research provides support for the positive link between allocentrism and OCB (e.g.,

Moorman and Blakely, 1995; Van Dyne, et al., 2000).

Idiocentrism, on the other hand, can be defined as an orientation towards viewing the self as separable from others (Triandis, 1989). Idiocentrics have a tendency to (1) have personal goals that are not necessarily correlated with the ingroup's goals; (2) emphasize personal attitudes, needs, rights and contracts when making decisions about how to behave or act; and (3) weigh carefully the costs and benefits of any relationship (Triandis and Bhawuk, 1997, p. 15). Applying the above theoretical link between allocentrism and OCB to the case predicting the relationship between idiocentrism and OCB, it is clear that the opposite would be expected. That is, if idiocentrics tend to view themselves as autonomous and tend to emphasize personal goals and needs, then it is less likely that they will engage in OCB. In fact,Ramamoorthy and Flood (2004)demonstrated that an idiocentric orientation is negatively related to the engagement in OCB.

In the section that follows we argue that examining the allocentric (idiocentric) relationship in context may have important implications for the hypotheses generated and the results found. Indeed, we argue that by more specifically contextualizing this relationship in a novel context, we bring to the surface distinct and salient contextual variables which in turn create a different expectation for the predicted relationships.

1.1.2. Context and the importance of contextualization

Where a study is conducted can have a marked impact on its results (Johns, 2006, p. 392). Indeed, context can be a multi-faceted, multi-level and powerful exogenous factor and it is for this reason that the impact of context on OCB has been noted as a fruitful area for future OCB research (Ehrhart and Naumann, 2004; Fischer et al., 2005; Paine and Organ, 2000; Podsakoff et al., 2000). Context shapes variability in employee behavior (Rousseau and Fried, 2001). More effort is needed to bring the specificities of context front and center in research (Mowday and Sutton, 1993). In an attempt to do this, we borrow from the work ofJohns (2006)who suggests that it is useful to distinguish between two levels of context whereby the greater national context provides the milieu in which an organizational unit is nested. Therefore, we specifically focus here on: (1) Lebanon-as-omnibus context and (2) unit level OCB as discrete context.

Thefirst,Omnibuscontext, focuses on context broadly defined or the socio-cultural, political and historical context of the Republic of Lebanon. By conceptualizing Lebanon-as-context and centralizing it we are engaging in whatRousseau and Fried (2001)described as Tier 1 contextualization of organizational research. Tier 1 research attempts to focus on the setting and describe features that can potentially impact or constrain what is studied as well as critically reflect on how the meaning of the constructs may be different in the new setting or cultural frame of reference (Rousseau and Fried, 2001). Engaging in this kind of research involves rich description and“informed reflection on the role that context plays in influencing the meaning, variation, and relationship among variables under study”(Rousseau and Fried, 2001, p. 7). To do this, researchers need to identify, highlight, and describe important contextual factors that may impact or constrain the behaviors of interest. Indeed, theorizing context in this way has increasingly been noted as an important area of focus in OB research in general (e.g.,Fischer et al., 2005; Mowday and Sutton, 1993; Tsui, 2004).

The second level, discrete context, focuses on a specific organizational unit level characteristic: unit level OCB. This contextual variable may moderate the relationship between allocentrism (idiocentrism) and an employee's engagement in OCB.Rousseau and Fried (2001)described this kind of contextualization as Tier 2 and it involves directly assessing the impact of a setting's characteristic(s) on employees. Therefore we are interested in testing the moderating influence of unit level OCB on the central relationship of interest. Therefore, both types of contexts form the backdrop in which the central relationship is reexamined.

1.2. Lebanon-as-context: why would we expect any difference?

Insofar as omnibus context shapes employee behavior by providing situational opportunities and constraints (Johns, 2006) it is expected that the unique national context of Lebanon may result in unexpected or unique behavioral patterns and relationships not previously observed in the OCB empirical research. The situational opportunities and constraints that derive from the socio-culture, political and historical characteristics of Lebanon fall within the content domain of omnibus context. Omnibus context therefore, broadly considered, serves as a behavioral landscape.

Previous work on the relationship between cultural values-OCB has been conducted (i.e., Moorman and Blakely, 1995; Ramamoorthy and Flood, 2004; Van Dyne, et al., 2000) in the USA and in Ireland. If one reads these articles it is apparent that details about the socio-cultural, political and historical context of these countries have been put on the periphery and have not been described. This sidelining of contextualization is certainly not unusual in management research. Indeed it has been suggested that there is a unicultural assumption underlying much of our knowledge in organizational science (Boyacigiller and Adler, 1991, p. 272) which has resulted in a lack of contextualization in thefield in general.

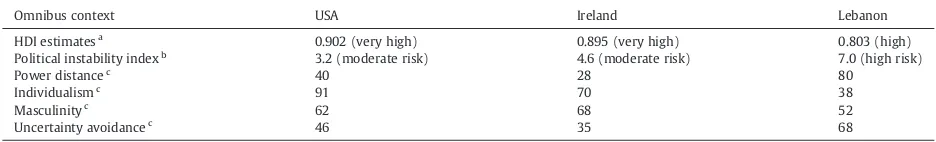

This sidelining has been facilitated by similarities in key macro-environmental factors across many of the research settings in North America and in Western Europe. For example, let us compare the national contexts of USA and Ireland where the allocentric (idiocentric) relationship have been previously examined. Select indicators suggest that the two countries rank“very high”on the Human Development Index (HDI: World Bank, 2010); have a moderate Risk of Political Instability (RPI:Economist Intelligence Unit, 2009); and according to the rankings onHofstede's (2000)national level culture values, are more individualist, tend to avoid uncertainty and tend to expect more of an equal distribution of power between members of society. Lebanon, on the other hand, differs substantially from Ireland and the USA on the same indicators whereby it is in a lower ranked category on the HDI, has a much higher risk of political instability and culturally can be described as collectivist, high on power distance and uncertainty avoidance (seeTable 1). These differences suggest a possibility of a noteworthy difference in omnibus context. We explore the contextual uniqueness of Lebanon in the following section.

1.3. Lebanon as omnibus context and its impact on the central relationship

experiencing political instability since the mid-1970s with the onset of afifteen year civil war which devastated the Lebanon's economy and infrastructure.

Lebanon, as noted, is a collectivist nation. It falls within Hofstede's“Arab cluster”which ranked 38 compared to a world average of 64 on the Individualism scale (Hofstede, 2000). This suggests that the omnibus context within Lebanon tends to have a social pattern that emphasizes close linkages among ingroup members and close adherence to ingroup norms and attitudes. Indeed it has been suggested that in collectivist nations“people from birth onwards are integrated into strong, cohesive ingroups, which throughout people's lifetime continue to protect them in exchange for unquestioning loyalty”(Hofstede, 2000;p. 225) and remains of utmost importance (Gomez et al., 2001).

Collectivism has specific implications for cognitive construal, for example, the salience of the ingroup starts early. In collectivist nations, like Lebanon, it has been suggested that people tend to construe the self as more interdependent and fundamentally connected to others (Markus and Kitayama, 1991) in his/her ingroup and therefore often tend to behave very differently toward ingroup versus outgroup members. The literature suggests further that ingroup members emphasize harmony, security, cooperation, loyalty and affiliation with members of the ingroup (Traindis, 1990) but not necessarily with outgroup members. People are tied to their ingroups in fact, according toHofstede (2000):

“Members of the we-group are distinct from other people in society who belong to they-groups or out-groups, and there are many such people and such out-groups. The ingroup is the major source of one's identity, and the only secure protection one has against the hardships of life. Therefore one owes lifelong loyalty to one's ingroup and breaking this loyalty is one of the worst things a person can do. Between the person and the ingroup a dependence relationship develops that is both practical and psychological”(Hofstede, 2000,p. 226–227).

It is this salience of the ingroup and of ingroup membership that forms the basis upon which we expect and hypothesize a different relationship between cultural values (i.e., allocentric and idiocentric) and OCB than has been previously noted in the literature.

Our core argument revolves around the theoretical salience of the ingroup, and the bearing that this salience may have on shaping employee perceptions and behaviors within organizations. Although this is relevant in contexts across the globe where the ingroup is salient, and therefore to international management studies in general, we use Lebanon as a case in point. We attempt to demonstrate that the rationale behind the proposed positive relationship between allocentrism and OCB (or negative relationship between idiocentrism and OCB) by researchers examining Irish and American omnibus context may not hold in omnibus contexts where ingroup membership is critically important, such as Lebanon. We suggest further that in Lebanon this is likely to be the case primarily because of the country's turbulent socio-political history and current reality. This turbulence we argue creates salient and divisive boundaries for group membership thereby decreasing the likelihood of coworkers being categorized as part of one's ingroup.

Throughout its history Lebanon has undergone significant political turmoil. For example, a civil war took place in Lebanon from 1975 until the early 1990s. This war left many terrible memories with the people of Lebanon as it destroyed much of the country's infrastructure and resulted in large scale emigration of its population to other countries (Amnesty International, 2007; Lebanon Higher Relief Council, 2007). The civil war was largely fought between religious groups and further complicated by sectarian, feudal and tribal affiliations. These groups are still vibrant and visible in Lebanon today. Indeed we suggest as noted byHofstede (2000)ingroup membership in collectivist nations carries with it a host of responsibilities and memories. Past occurrences often retain full relevance for the present.

Lebanon today has been described by its own historians as well as by foreign observers as a“collage”of different communities living together (p162, NHDR, 2009).There are seventeen recognized religious sects in Lebanon. The collage of various religious sects is further complicated by political divisions (some along sectarian lines) as well as feudal and tribal underpinnings (Sidani, 2005). Sectarian and political affiliation plays a central role in the lives, or at the very least, the ingroup identity of many Lebanese (Khairallah, 1994). This sense of ingroup identity along sectarian (and political) divisions has been noted byHaddad (2001)and others (e.g.,Henry and Hardin, 2006).

Haddad (2001)investigated Maronite Christians' socio-political attitudes, particularly with regard to the Taif Accord. The Taif Accord marked the end of the civil war and guaranteed equal parliamentary representation for Christians and Muslims in Lebanon

Table 1

Select macro-environmental factors that make Lebanon unique from other OCB research contexts.

Omnibus context USA Ireland Lebanon

HDI estimatesa

0.902 (very high) 0.895 (very high) 0.803 (high) Political instability indexb 3.2 (moderate risk) 4.6 (moderate risk) 7.0 (high risk)

Power distancec 40 28 80

Individualismc

91 70 38

Masculinityc

62 68 52

Uncertainty avoidancec

46 35 68

a UNDP and CDR (2009)Human Development Report. b Economist Intelligence Unit (2009).

c

Hofstede (2000).

thereby threatening the formalized higher status of Maronites. Interviewing a representative sample of Maronites,Haddad (2001)

found that in post-war Lebanon, they showed high ingroup attachment. This ingroup attachment was manifested by their leadership preference, their cohesiveness, solidarity and loyalty, and their pride in being part of the Maronite ingroup.

A person's ingroup identity is not limited to matters of personal choices (e.g., religious piety and political affiliation) but is very much intertwined in conceptions of“citizenship”,“nationalism”, and the very process of civil participation (NHDR, 163). For example, the founding charter of Lebanon and National Pact dictates a governmental division of power that organizes society on a sectarian basis. In practical terms this means that sectarian divisions are clearly seen in society, government, the judicial system and everyday attitudes and behaviors.

The points made above suggest that in Lebanon there is a general pattern of ingroup identification. Indeed, as Kamal Salibi depicts in his bookA House of Many MansionsLebanon is a divided country (Salibi, 1993). People's affiliations to various groups often, according to (Haddad 2001), dictate divisions in voting outcomes, real estate transactions, choice of school, as well as where one chooses to live. Ingroup affiliation is of paramount importance“when it comes to social personal intercourse. While it is true that people meet each other at work, this may not correspond necessarily to a sectarian choice; it could be simply a question of convenience”(p. 472,Haddad, 2001) or necessity. The boundary between ingroup and outgroup is not a matter of sharing workspace or tasks, but rather is a matter of socio-political history, religious piety, and even bloodshed across group lines.

Given the strong relevance of ingroups within Lebanon in general, it is likely that performance of OCB would be less culturally mandated in the workplace where coworkers are likely to be outgroup members. Therefore, in this context, it is likely that perceptions of OCB refer to not only behaviors that are not required by the organization, but also those that are directed at co-workers who belong to different outgroups. Such behaviors are perceived as beyond what is required, not mandated by cultural expectations, and therefore more noteworthy, worthy of praise and even reward.

Within this omnibus context, the patterns of individual level relationships may fare differently than has been suggested previously in the literature. Not all individuals within this context give salience to ingroup and outgroups to the same extent. For individuals who have a greater allocentric orientation and therefore give greater salience to group membership, it is likely that coworkers are less likely to be perceived as ingroup members than previously assumed in the research. This guarded identification with an ingroup has specific implications for the expected relationship between allocentrism and OCB such that ingroup membership is likely to be reserved for family members, or people who share strong religious and sociopolitical links (not coworkers). Thereforeno relationshipis expected to exist between an allocentric orientation and engagement in OCB at work in this omnibus context. Although we do not formally set this hypothesis we will nonetheless test to check that indeed allocentrism is not related to the performance of OCB by individual employees in Lebanon.

For employees with a more idiocentric orientation, on the other hand, it is a different story. First, by very definition, an employee with an idiocentric orientation is likely to place ingroup membership more on the periphery of what is important in workplace interactions and behaviors. Second, he/she is likely to view personal goals, needs, and rights as more important in guiding his/her behavior than a focus on others. Previous qualitative research on OCB in the Lebanese context suggests that 42.5% (n = 40) of employees believe that engaging in OCB would lead to formal rewards and 79.2% (n = 53) believe that such behavior would lead to informal rewards (Karam and Kwantes, 2008). Based on this therefore, engagement in OCB is more likely by because he/she perceives this behavior to be personally beneficial. Taken together, and when considered within the omnibus context of Lebanon where OCB is likely to be perceived as worthy of praise and reward, we hypothesize a positive relationship between idiocentrism and OCB in the Lebanese work context.

Hypothesis 1. Idiocentrism will be positively related to the performance of OCB by individual group employees in Lebanon.

Thus far we have attempted to ground our examination of the central relationship within the unique omnibus context of Lebanon. We now turn our attention to discrete context. Indeed if the positive idiocentric-OCB relationship holds then it is likely to be even stronger in a discrete context that emphasizes and is aligned with employee OCB performance (i.e., unit level OCB).

1.4. Unit level OCB as discrete context: shaping employee behaviors at work

In this paper we conceptualize OCB at the unit level of analysis and theory (Ehrhart and Naumann, 2004):Unit Level OCB. By its very structure unit level OCB serves as a discrete context for individual perceptions, attitudes and behaviors (Kozlowski and Klein, 2000). As such this construct is a distinct collective level phenomenon which concerns the extent to which the workgroup, as a whole, engage in OCB within the unit (Euwema et al., 2007). Unit level OCB is a shared pattern of OCB-type behaviors that can in part characterize unit member interactions as well as the context within which they interact.

Most also specify that the behavior of the group is directed at within-group members or at the organization as a whole (save

Chen et al.'s, 2005).

Insofar as discrete context shapes employee behavior by providing situational opportunities and constraints (Johns, 2006) it is expected that the unit level OCB may impact employee behavioral patterns at work. According toJohns (2006)one of the salient dimensions of discrete context is the social context. Social context can influence behavior in a number of ways (e.g., restricting range, reversing signs, etc.). In the current research we suggest that if unit level OCB has an a posteriori permanence (Morgeson and Hofmann, 1999) it may serve as a discrete unit level context that influences employee engagement in OCB (Hypothesis 2) as well as the employee level relationship between cultural values and OCB (Hypotheses 3 and 4). This is likely the case because unit level OCB will serve to partly characterize the unit's social environment by providing cues about appropriate within-group actions and interactions (Salancik and Pfeffer, 1978). Group Norm theory suggests further that in the presence of unit level OCB as a discrete contextual variable, group members will likely perceive that OCB occurs relatively frequently, and therefore inferring that the group as a whole desires and supports the individual performance of OCB as well as the between-person interchanges in the form of OCB-type interactions. Therefore, we suggest that if unit level OCB is present in a work unit, then employees will likely engage in more OCB. Based on this therefore we expect a positive cross level relationship between unit level OCB and employee engagement in OCB.

Hypothesis 2. Unit level OCB is positively related to the performance of OCB by individual group employees.

Further extending this line of reasoning to the central relationship of interest, the question becomes: If unit level OCB is present in a work unit, what impact will this have on the relationship between an employee's cultural values and his/her engagement in OCB? We suggest that again unit level OCB will function as a discrete contextual variable which may moderate the proposed relationship between allocentrism (idiocentrism) and OCB.

There is some research to suggest that contextual variables (e.g., unit level OCB) may serve to alter individual level relationships.Van Dyne et al. (2000), for example, discuss the concept of situational strength and suggest that:

“In a strong situation, well recognized and widely accepted guidelines for interaction reduce inter-individual variability. Most individuals in a strong situation construe the situation in the same way and tend to conform to expectations and norms…In contrast, individual dispositions are more influential in a weak situation where individuals exhibit a wider range of appropriate attitudes and behaviors.”(Van Dyne et al., 2000, p. 5).

Therefore, based on this, it is suggested here that cultural values as a particular form of individual dispositions may have less predictive power in situations where the discrete context is characterized by unit level OCB. In units where unit level OCB exists the demand characteristics for engagement in OCB are present and therefore employees, regardless of whether they are allocentric or idiocentric, will be more likely to engage in OCB.

This rationale is supported byTriandis and Bhawuk (1997)claim that although an individual's cultural values may lead him/her to behave in a particular way; these are just tendencies and are not inevitable and immutable patterns of behavior. Highlighting this point,Triandis and Bhawuk (1997)state further that allocentrics will not behave in an allocentric way inall situations but only in most, and conversely idiocentrics will behave as allocentrics do in a number of situations (p. 29). It is proposed here, therefore, that differences in discrete context may lead to behavior that is not necessarily consistent with an individual's cultural orientation or, more specifically, that unit level OCB serves as a contextual moderator of the relationship between cultural orientation and OCB. This implies that there may be an interaction between the discrete group context and individual allocentrism (idiocentrism) such that a group member's actual behavior may change in different discrete contexts (Triandis and Bhawuk, 1997, p. 118).

Therefore, we hypothesize that if allocentrics are working in a discrete context that is characterized by unit level OCB then it is likely that the group members will feel more compelled to act in a pro-social manner toward coworkers who are not necessarily in their ingroup. Consequently, this suggests a positive relationship between allocentrism and OCB.

Hypothesis 3. Unit level OCB will moderate the relationship between allocentrism and performance of OCB. Specifically, whereas allocentrism is expected to be unrelated to OCB at an individual level, this relationship will be positive and significant in groups where unit level OCB is high.

The same is expected for the relationship between unit level OCB and idiocentrism in the context of unit level OCB.

Hypothesis 4. Unit level OCB will moderate the relationship between idiocentrism and performance of OCB, such that idiocentrism and OCB will be positively related as unit level OCB increases.

2. Method

2.1. Research context

The specific sample for this research was drawn from the Lebanese food service sector. The types of companies that exist in this sector include: fast food companies, casual dining restaurants, and specialty food companies. The naturally occurring, or

existing, Food Service Groups (FSGs) drawn from within these companies were used because they represent meaningful units within these companies and within this sector. Examples of FSGs include: the kitchen group of a large restaurant, thefloor staff group of a casual dining restaurant, and thefloor sales staff of a large bakery shop.

2.2. Participants

The total sample consisted of 553 employees and 79 managers working in 62 FSGs drawn from seven companies. The number of employees in each group ranged from four to 22 employees. The majority of employees (83.9%) were between the ages of 18 and 30. Most were male (71.6%), had Arabic as theirfirst language of (96.4%); and had attended some university courses or completed an undergraduate degree (64.2%). Only 17.5% of the employees had lived outside of Lebanon at some point in their lives. The sample for this study was drawn from four Lebanese provinces (i.e., Beirut, North, South, and Mount Lebanon) with 36.9% living and 38.5% working in urban areas. The percentage of employees who work in the specific work areas/positions are as follows: 14.3% in kitchen; 68.5% infloor; 7.2% in administrative/support; and 8.0% in delivery.

2.3. Procedure

Data were obtained with the use of two separate questionnaires: an employee and a manager questionnaire. Both questionnaires were available in both the original English form as well as in Arabic translated form. Translation of both questionnaires from English into Arabic was done by a professional translator. The resultant Arabic questionnaires were then back translated into English by a second professional translator to ensure accuracy. All participants chose to complete the Arabic translation.

2.4. Measures

2.4.1. Demographic information

All participants were asked to provide basic demographic information including: age, gender, language, education, etc.

2.4.2. Unit level OCB

Measures of unit level OCB were collected on the employee questionnaires. This measure was originally developed byWilliams and Anderson (1991)to measure OCB. Following the recommendations ofChan (1998)the referent for all items was changed to reflect the group level rather than the individual level. Employees were asked to rate the level of unit level OCB in their groupas a wholeon ten separate items (e.g., the employees in this group help others who have heavy workloads). All ratings were done using a Likert-type scale ranging fromto a very small extent(1) toa great extent(5). The reliability estimate for this scale was measured with a Cronbach's alpha of 0.81.Nunnaly (1978)has indicated 0.7 to be an acceptable reliability coefficient.

2.4.3. Allocentrism and idiocentrism

The measures of allocentrism and idiocentrism used were originally developed bySingelis et al. (1995)and modified by

Triandis and Gelfand (1998). Eight items measuring allocentrism and eight measuring idiocentrism were included on the employee questionnaire. The referent for all items was the individual. Employees were asked to make their ratings on a Likert-type scale ranging fromto a very small extent(1) toa great extent(5). The Cronbach's alpha for the complete scale was 0.72.

2.4.4. Organizational citizenship behavior

Each group manager was asked to rate the level of OCB performed by each of the employees under his/her supervision. The measure of OCB was developed byWilliams and Anderson (1991), with the individual employee as the referent for all items. Five items were used and all ratings were done using a Likert-type scale ranging fromto a very small extent(1) toa great extent(5). The Cronbach's alpha for this scale was 0.84.

3. Results

3.1. Justification for aggregation

In order to assess whether unit level OCB exists in the 62 different FSGs sampled, the researchers examined measures of within-group agreement through the calculation of rWG(j)(James et al., 1984; LeBreton et al., 2005); as well as measures of between-group differences through the calculation of an index of the reliability of group means (ICC(2)—Bliese and Halverson, 1998) and an index of interrater reliability (ICC(1)—James, 1982). The results suggest that: unit level OCB existed in 57 of the 62 FSGs thereby providing support for aggregation to the unit level for analysis. In general, the mean rWG(j)for unit level OCB across the 62 groups was 0.86, ranging from 0.31 to 0.98. These two results therefore, provide initial justification for aggregation of individual group member ratings of unit level OCB to the FSG level in 57 groups.

F-test (Castro, 2002). However, due to the unequal number of respondents in the FSGs, an adjusted‘n’was used in the calculation of the sum of squares upon which theF-test is based (seeBliese and Halverson, 1998). For unit level OCB the ICC(1) was 0.23, whereF(61, 486) = 3.70 and was significant at the 0.01 level; thereby indicating that 23% of the variability in employees' unit level OCB responses are a function of FSG membership and providing further support for aggregation. Measures of practical significance (Barnette, 2001) were considered whereby ICC(1) was calculated for unit level OCB (2.82). This result supports aggregation to the group level (Muthen and Satorra, 1995). Taken together, the calculation of these indices provides good support for the emergence of unit level OCB in the different FSGs.

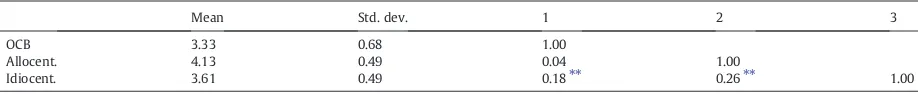

3.2. Means, standard deviations, and intercorrelations for variables

Table 2provides the means, standard deviations, and intercorrelations for OCB, allocentrism and idiocentrism. Nine FSGs were dropped from the analyses due to incomplete data sets. Therefore, although unit level OCB was demonstrated to have emerged in 57 FSGs, the actual hypotheses testing was conducted with a total 48 FSGs composed of a total of 386 employees and 48 managers. These FSGs ranged in size from four to 17 employees with a mean size of approximately eight. The demographic characteristics of these participants very closely mirrored those described for the full sample.

3.3. Analytic strategy: hierarchical linear modeling

Hierarchical linear modeling was used to test all of the proposed hypotheses. The hypotheses included: a lower-level effects (Hypothesis 1), a cross level main effect (Hypothesis 2), as well as cross level moderating effects (Hypotheses 3 and 4). Analyses were computed using HLM 6 © Scientific Software International, Inc. The analysis followed sequential steps and standard HLM practices (Byrk and Raudenbush, 1992). In total the analysis included four models.

3.4. Model one: testing for between group variances

Thefirst model examines whether there is variation in OCB at both the individual and FSG levels. Results suggest systematic between group variance in OCB (τ00= 0.15,df= 47,χ2= 221.20,pb0.001) and therefore suggests that exploration of unit level

antecedents is worthwhile. This model also produces statistics that can be used to recalculate the ICC(1) for the 48 FSGs. ICC(1) was significant and indicated that 32% of the variance in OCB lies between these FSGs. thereby meeting thefirst requirement for testing the crosslevel main (Hypothesis 2: unit level OCB and OCB) and moderating effects (Hypotheses 3 and 4) hypothesized.

3.5. Model two: testing the individual level relationships

This second type of model was used to test the individual level relationship hypothesized in this study (Hypothesis 1). The results suggest that in the Lebanese work context, as expected but contrary to what would be expected based on the Western-based literature, idiocentrism is positively related to an individual's performance of OCB (γ10= 0.20,se =0.08,t(47) = 2.54, pb0.05). The magnitude of this relationship was R2= 0.06. Furthermore, the allocentric–OCb relationship was also tested and it was found that allocentrism is not related to the performance of OCB (γ10= 0.07,se= 0.07,t(47) = 1.07).

In addition to the hypothesis testing, this model also calculates the variance estimates for the predictors' intercept parameters (τ00). These estimates were significant for the allocentrism–OCB relationship (τ00= 0.15,df= 47,χ2= 206.83,pb0.001) as well as

for the relationship between idiocentrism–OCB (τ00= 0.13,df= 47,χ2= 158.43,pb0.001). The significance of these relationships

indicates that the precondition for testing the cross level main effect relationship between unit level OCB and employee OCB (Hypothesis 2) has been met. The results also show that the variance estimates for the predictors' slope parameters (τ11) were significant for the relationship between idiocentrism-OCB (τ11= 0.08, df= 47, χ2= 66.92, pb0.05) thereby meeting the

precondition for testingHypothesis 4. The precondition for testing the relationship between allocentrism–OCB however was not met. This latterfinding suggests that the allocentrism–OCB relationship (Hypothesis 3) cannot be tested with these data.

3.6. Model three: testing the crosslevel relationship between unit level OCB and OCB

The third model tested the crosslevel main effect through the calculation of t-tests associated with the level 2 slope parameter (γ01). The results of thet-test indicate a reduction in slope variance at level 1 after including level 2 predictors and therefore

Table 2

Individual level statistics and correlations for global constructs.

Mean Std. dev. 1 2 3

OCB 3.33 0.68 1.00

Allocent. 4.13 0.49 0.04 1.00

Idiocent. 3.61 0.49 0.18⁎⁎ 0.26⁎⁎ 1.00

Note.n= 386.

⁎⁎ pb0.01. One-tailed tests.

provides support for this hypothesis (γ01= 0.56, se= 0.18,t(46) = 3.06,pb0.01). Therefore, indicating that individuals will display higher levels of OCB in FSGs with higher levels of unit level OCB. This was the case even after controlling for individual level allocentrism and idiocentrism. Furthermore, R2provides an estimate of the change in variance of the intercept with the addition of the level-2 predictor. For this model R2was 0.20. This third model also suggests that signi

ficant residual variance across groups remains to be explained (τ00= 0.12,df= 46,χ2= 161.18,pb0.001) and therefore that it is useful to test crosslevel moderation.

3.7. Model four: testing crosslevel moderation of unit level OCB

The fourth andfinal model can be used to test crosslevel moderation. Only the moderating effect of unit level OCB on the relationship between idiocentrism and OCB (Hypothesis 4) could be tested. Thisfinal estimation used grand mean centering and the results suggest that the parameter estimates were marginally significant (grand mean centered:γ11= 0.29,se= 0.16, t(46) = 1.85,p =0.07). When the outliers were dropped from the analysis, the parameter estimates were significant (grand mean centered:γ11= 0.04,se= 0.02,t(46) = 2.01,p =0.05).Table 3provides a summary of all the estimated models from the HLM.

4. Discussion

Context, as has been argued in this paper is of paramount importance when studying organizational behavior in general and OCB in specific. Despite the attention paid to OCB at the individual level, little attention has been paid to the context within which it occurs.Hackman (2003)noted that most organizational researchers tend to look to lower levels of analysis in order to explain many phenomenon rather than paying attention to the context within which attitudes form and behavior occurs. He suggested that it would be profitable for research to also “bracket up,” or move up a level in order to gain a better understanding of a phenomenon. In contrast with much of the previous research in the area which tends to stay at a single level or to “drill down” to better understand work attitudes and behavior, this research attempted to drill up and down by conducting a cross level empirical examination of the OCB phenomenon.

In addition to this, we have attempted to“bracket up”further by attempting to begin to discuss how the Lebanese omnibus context may shift expectations about how an individual's cultural values relate to his/her performance of OCB. Taking omnibus context more into account helps to move organizational studies in a direction that takes cultural differences more seriously by inching away from an implicit American perspective that assumes universality (Boyacigiller and Adler, 1991).

If approached in an uncontextualized manner it may be easy to hypothesize a positive relationship between allocentrism and OCB and a negative relationship between idiocentrism and OCB anywhere is the world. But if we approach this same relationship in a contextualized manner it is possible that in unique contexts the nature (and the direction) of the relationship may change. For example, as is the case in Lebanon, allocentric employees who have been (and continue to be) the victims/observers/perpetrators of civil violence and turbulence, it is possible that pro-social actions and energies may be reserved for ingroup members. Examining engagement in OCB in a more contextualized manner may expand our understanding of this organizational behavior phenomenon.

From a contextualized point of view, researchers are better able to consider how OCB is fundamentally shaped through context as well as the experiences individuals interacting in a specific socio-political, economic, and cultural context. Knowledge about and the meaning of OCB may indeed be something that is generated and maintained between people living and interacting with one another in a particular context over time. From this epistemological stance, what is considered to be OCB in an omnibus context may depend more on the specific contextual factors that influence of particularistic, relational, or dynamic char-acteristics on employee or supervisor perceptions of the construct under study (Van Dyne et al., 1995: 221). In effect, cross cultural researchers may find it useful to conceptualize and examine organizational behaviors as specific acts-in-context (Landrine, 1995).

The balance between approaching organizational phenomenon within a specific context versus a search for larger patterns across contexts is one that international management researchers must address. In order to better contribute to international management studies research can attempt to avoid reductionism and focus on identifying patterns that are applicable across more than a single setting. This being said, along the lines ofRousseau and Fried (2001) and Tsui (2004), we believe that international management models can also greatly benefit from well designed context-sensitive research. Although the

Table 3

HLM results for crosslevel relationships between unit level OCB, cultural values and OCB.

Level Hypothesis Model Relationship γ s.e. t Individual – Random coefficient regression Allocentrism–OCB 0.07 0.07 1.07

1 Idiocentrism–OCB 0.20 0.08 2.54⁎

Cross-level 2 Intercept as outcome Top-down: unit level OCB on OCB 0.56 0.18 3.06⁎⁎ 4 Slopes as outcomes Moderation: unit level OCB on idiocentrism–OCB 0.29 0.16 1.85+

Unit level OCB on idiocentrism–OCB (outliers dropped) 0.04 0.02 2.01⁎

management literature has generally underemphasized context, the growing importance of taking context into consideration is being highlighted by many (e.g.,Cappelli and Sherer, 1991; Johns, 2006; Rousseau and Fried, 2001). Research on omnibus context, if done correctly should produce contextualized knowledge on the one hand and contribute to global knowledge on the other (Tsui, 2004, p. 491).

The results of our research clearly indicated that both omnibus and discrete contexts matter when seeking to understand what predicts helping behaviors in organizations. While it may be tempting to use culture theories as the basis for a typology of omnibus contingencies, culture interacts with a number of other factors to influence organizational behavior as well.Aycan (2000), for example, highlights three theories that also explain variations in organizational behavior: contingency theory (including specific contextual aspects such as industrialization and technology), political-economy theory, and societal effect theory. The interaction between the explanations posited by each of these perspectives lends a very complicated view of organizational behavior, and may suggest that each context must be taken on a case by case basis in order to provide a true understanding of these phenomena. Future theorizing and research is warranted, however, as it may uncover larger contextual patterns that provide greater utility in understanding organizational behavior-in-context.

4.1. Studying the allocentric (idiocentric)–OCB relationship in a single country context

When the relationship of allocentrism or idiocentrism with OCB is examined in Lebanon, the results suggest that the omnibus context plays a role such that the expected relationship may shift. Indeed, as expected, no relationship was found between allocentrism and OCB, which is contrary to previousfindings with Western samples (e.g.,Moorman and Blakely, 1995; Van Dyne et al., 2000). These variant results may be consistent withTriandis et al.'s (1988)suggestion that in certain collectivist cultures, the individual has few ingroups (often just one) and everybody else is in the outgroup. Based on this, it could be that employees do not perceive their coworkers to be ingroup members but rather as outgroup members and therefore, do not feel an obligation toward supporting coworkers nor toward maintaining a positive organizational, social, and psychological work environment.

Further research may explore whether the meaning of engaging in OCB differs depending on the salience of the ingroup for the person in the specific national context. Perhaps there is a continuum of ingroup-ness that is correlated with national level factors (e.g., socio-cultural, political stability, etc.). This continuum could include: people familiar to us, our colleagues, our friends, people within our support network, people whom we depend on for survival. In a turbulent environment such as Lebanon it may be that people may include only people in the latter two categories in their ingroup. To the extent that this is the case, these results provide a strong caution against assuming that the formation of workgroups will automatically lead to the perception by employees that they belong to this group, or that fellow workgroup employees will be perceived as ingroup members. Exploring these types of questions may be an interesting area for future research.

The positive relationship found between idiocentrism and OCB may also suggest the importance of omnibus context where an employee who has a tendency towards viewing the self as separate from others is likely to engage in OCB. Again, this result is different from previously established negative relationship between idiocentrism and OCB with Irish blue collar workers (Ramamoorthy and Flood, 2004). In fact, some evidence is emerging in the literature that allocentrism and idiocentrism do not always function identically in different social cultural contexts. In a comparative study of Indian and American engineers, for example, found that allocentrism was related to normative commitment in the Indian context and not in the American context, while idiocentrism was related to affective commitment in the American context but not in the Indian context (Kwantes, 2009). Future researchers may wish to involve additional levels of theory and analysis as discussed byFischer et al. (2005).

4.2. OCB in the discrete context of unit level OCB

In addition to providing support for the idea that internalized cultural values can impact employee behavior, and the suggestion that the omnibus context may affect individual employee behaviors, this research also highlighted the importance of more discrete contextual factors. The particular workgroup in which an employee spends his or her time may provide salient directions for individual behavior in the form of unit level OCB. Once unit level OCB has emerged in an organizational unit it assumes an a posteriori permanence (Morgeson and Hofmann, 1999, p. 253) that has identifiable structural properties. These properties can be described in terms of unit level construct type (Kozlowski and Klein, 2000) as well as assumptions of variability (Klein et al., 1994).

The emergence of unit level OCB does seem to make a difference with respect to the extent of engagement in OCB by individual employees. A discrete context as revealed through unit level OCB provides a social environment in which employees work and this context provides specific cues about OCB as an appropriate form of within-group behavior. The discrete context of employees may provide cues that employees use to construct and interpret appropriate and inappropriate work behavior. Although employees perceive and react to an“objective workplace reality,”this reality is partially constructed from the cues provided by the social context of the workgroup (Thomas and Griffin, 1983). These cues are powerful instruments of social influence such that coworkers are likely to replicate what they perceive to be‘normal’behavior (Bommer et al., 2003).

4.3. The moderating influence of unit level OCB

It was originally hypothesized that the level of unit level OCB would moderate the relationship between individual level allocentrism as well as individual level idiocentrism and individual performance of OCB. In light of the above discussion on

discrete contextual effects, it may not be surprising that it was not possible to test the moderating effect of unit level OCB for allocentrism and OCB but only for idiocentrism and OCB as this research was conducted in a collectivistic omnibus context. The constraints of unit level OCB within a larger collectivistic context such as Lebanon may have a greater impact on idiocentrics than on allocentrics.

Further, theorists such asMischel (1968)suggest that situations where specific and strong norms have emerged tend to result in constraints on individual behavior. It may be further supposed that these constraints are more obvious for those whose values do not match the dominant values (e.g. idiocentrics in a collectivistic context). In this research it was hypothesized that the level of unit level OCB would moderate the relationship between individual level idiocentrism and the performance of OCB by individual group employees. Marginal support was found for this hypothesis. This implies, in general, that the context of unit level OCB alters the relationship between idiocentrism and OCB. More specifically, this implies that idiocentric-oriented employees are likely to engage more in OCB when the level of unit level OCB in their work group is higher, suggesting the strength of such proximal norms and constraints.

5. Limitations

The benefit of incorporating voices from a new cultural context in OCB research also provides a limitation to the research, and that limitation concerns the generalizability of thefindings to other cultures as well as within Lebanon in general. Although the sample used in these studies was obtained from seven independent food service companies, this sample may not be representative of the food service sector in general or the working population on Lebanon. As the food service companies were not randomly sampled from the food service sector but rather represented companies who were approached and who agreed to participate, generalizability may be further reduced. Additionally, males were overrepresented in the sample (71.6%), which does not reflect the general working population in Lebanon. Finally, 83.9% of the sample was between the ages of 18 and 30 and therefore this age group may have been overrepresented in the sample.

6. Application

In addition to the contributions to theory, this research raises some important practical issues. OCB, by definition, are behaviors that contribute to organizational effectiveness (e.g.,Dunlop and Lee, 2004; Koys, 2001; Podsakoff and Mackenzie, 1994) and therefore increasing the occurrence of these behaviors on the part of employees is in the best interest of organizations. The results of this research offer a way to enhance the likelihood that individual employees will engage in these behaviors. Rather than focusing only on individual level antecedents, group level constructs (i.e. unit level OCB) provide a way to understand the context within which these activities are most likely to occur. If unit level OCB exists within a workgroup, it is more likely that, regardless of individual level propensity to engage in these behaviors, people will engage in OCB. This can perpetuate itself as these norms are likely to be enforced by group members as well as taught to new group members through socialization processes. This suggests therefore that training for ingroup cohesiveness and for better team performance may facilitate the emergence of unit level OCB and therefore engagement in OCB by individual employees.

Thefindings of this research may be of particular interest to managers working in organizations in the Middle East as it begins to shed light on an important and positive form of employee behavior. This study actively attempts to test whether accepted relationships derived and tested in Western contexts actually hold up in a local Lebanese workplace. It is important that although cultural values and OCB remain significantly related, the dynamics of this relationship are very different than what we understand to be the case from the Western based literature. This highlights a need for managers and practitioners alike to more actively engage in context specific (localized) assessment of practices, policies and procedures that may be run-of-the-mill in the West.

7. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

This research was made possible through a Canadian Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council Doctoral Fellowship and an American University of Beirut University Research Board Grant awarded to thefirst author.

The authors wish to thank the editor and reviewers for their helpful suggestions on earlier drafts of this paper.

References

Amnesty International, 2007. Israel/Lebanon underfire: Hizbullah's attacks on northern Israel. Retrieved July 2, 2007, fromhttp://web.amnesty.org/library/index/ engmde020206.

Aycan, Z., 2000. Cross-cultural industrial and organizational psychology. Contributions, past developments, and future directions. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 31, 110–128.

Barnette, J.J., 2001. Empirically based characteristics of effect sizes used in ANOVA. American Public Health Association Annual Meeting. Statistics Program, Atlanta, GA. Bliese, P.D., Halverson, 1998. Group size and measures of group-level properties: an examination of eta-squared and ICC values. Journal of Management 24, 157–172. Borman, W.C., Motowidlo, S.J., 1993. Expanding the criterion domain to include elements if contextual performance. In: Schmitt, N., Borman, W.C., Associates

(Eds.), Personnel Selection in Organizations. CA: Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, pp. 71–98.

Boyacigiller, N., Adler, N., 1991. The parochial dinosaur: organizational science in a global context. Academy of Management Review 16 (2), 262–290. Castro, S.L., 2002. Data analytic methods for the analysis of multi-level questions: a comparison of intraclass correlation coefficients, rWG(J),hierarchical linear

modeling, within- and between-analysis and random group resampling. The Leadership Quarterly 13, 69–93.

Cappelli, P., Sherer, P.D., 1991. The missing role of context in OB: the need for a meso-level approach. Research in Organizational Behavior 13, 55–110. Chan, D., 1998. Functional relations among constructs in the same content domain at different levels of analysis: a typology of composition models. Journal of

Applied Psychology 83, 234–246.

Chen, X.P., Lam, S.S.K., Naumann, S.E., Schaubroeck, J., 2005. Group citizenship behavior: conceptualization and preliminary tests of its antecedents and consequences. Management and Organizational Review 1, 273–300.

Choi, J.N., Sy, T., 2009. Group-level organizational citizenship behavior: effects of demographic faultlines and conflict in small work groups. Journal of Organizational Behavior 31 (7), 1032–1054.doi:10.1002/job.661.

Clark, T., Knowles, L.L., 2003. Global myopia: globalization theory in IB. Journal of International Management 9, 361–372.

Dunlop, P.D., Lee, K., 2004. Workplace deviance, organizational citizenship behavior, and business unit performance: the bad apples do spoil the whole barrel. Journal of Organizational Behavior 25, 67–80.

Economy Watch, 2009. Retrieved from:http://www.economywatch.com/.

Economist Intelligence Unit, 2009. Political instability index: vulnerability to social and political unrest. Retrieved Oct. 3, 2010, from:http://viewswire.eiu.com/ index.asp?layout=VWArticleVW3article_id=874361472rf=0.

Ehrhart, M.G., 2004. Leadership and procedural justice climate as antecedents of unit-level organizational citizenship behavior. Personnel Psychology 57, 61–95. Ehrhart, M.G., Bliese, P.D., Thomas, J.L., 2006. Unit level OCB and unit effectiveness: examining the incremental effect of helping behavior. Human Performance 19, 159–173. Ehrhart, M.G., Naumann, S.E., 2004. Organizational citizenship behavior in work groups: a group norms approach. Journal of Applied Psychology 89, 960–974. Ersoy, N., Born, M., Derous, E., van der Molen, H., 2010. Antecedents of organizational citizenship behavior among blue and white collar workers in Turkey.

International Journal of Intercultural Relations.

Euwema, M., Wendt, H., Van Emmerik, I., 2007. Leadership styles and group organizational citizenship behavior across cultures. Journal of Organizational Behavior 28, 1–23. Fischer, R., Ferreira, M.C., Assmar, E.M.L., Redford, P., Harb, C., 2005. Organizational behaviour across cultures: theoretical and methodological issues for developing

multi-level frameworks involving culture. International Journal of Cross Cultural Management 5, 27–48.

Gelfand, M., Leslie, L., Fehr, R., 2008. To prosper, organizational psychology should adopt a global perspective. Journal of Organizational Behavior 29 (4), 493–517. Gomez, B., Kirkman, L., Shapiro, L., 2001. Culture and procedural justice: the influence of power distance on reactions to voice. Journal of Experimental Social

Psychology 37, 300–315.

Hackman, J.R., 2003. Learning more by crossing levels: evidence from airplanes, hospitals, and orchestras. Journal of Organizational Behavior 24, 905–922. Haddad, S., 2001. A survey of Maronite Christian socio-political attitudes in postwar Lebanon. Christian–Muslim Relations 12 (4), 473–489.

Henry, P.J., Hardin, C.D., 2006. The contact hypothesis revisited: status bias in the reduction of implicit prejudice in the United States and Lebanon. Psychological Science 17 (10), 862–868.

Hofstede, G., 2000. Culture's Consequences: International Differences in Work-Related Values. Sage Publication, Thousand Oaks, CA. James, L.R., 1982. Aggregation bias in estimates of perceptual agreement. Journal of Applied Psychology 67, 219–229.

James, L.R., Demaree, R.J., Wolf, G., 1984. Estimating within-group interrater reliability with and without response bias. Journal of Applied Psychology 78, 306–309. Johns, G., 2006. The essential impact of context on organizational behavior. Academy of Management Review 31 (2), 386–408.

Karam, C.M., Kwantes, C.T., 2008. Qualitative Exploration of Organizational Citizenship within Lebanon. Paper presented at the Annual Academy of International Business Conference, Milan, Italy.

Khairallah, D., 1994. Secular democracy: a viable alternative to the confessional system. In: Collins, D. (Ed.), Peace for Lebanon? From War to Reconstruction. Boulder CO, Lynne Rienner.

Klein, K.J., Dansereau, F., Hall, R.J., 1994. Level issues in theory development, data collection and analysis. Academy of Management Review 19, 195–229. Koys, D.J., 2001. The effects of employee satisfaction, organizational citizenship behavior, and turnover on organizational effectiveness: a unit-level, longitudinal

study. Personnel Psychology 54, 101–114.

Kozlowski, S.W.J., Klein, J.K., 2000. A multi-level approach to theory and research in organizations: contextual, temporal and emergent processes. In: Klein, J.K., Kozlowski, S.W.J. (Eds.), Multilevel Theory, Research and Methods in Organizations. Foundations, Extensions, and New Directions. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, pp. 3–90. Kwantes, C.T., 2009. Culture, job satisfaction and organizational commitment in India and the United States. Journal of Indian Business Research 1 (4), 196–212. Landrine, H., 1995. Introduction: cultural diversity, contextualism, and feminist psychology. In: Landrine, H. (Ed.), Bringing Cultural Diversity to Feminist

Psychology. APA, Washington, DC, pp. 1–20.

Lebanon Higher Relief Council, 2007. Recovery and reconstruction facts. Retrieved July 29, 2007, fromhttp://www.lebanonundersiege.gov.lb/english/F/Main/index. LeBreton, J.M., James, L.R., Lindell, M.K., 2005. Recent issues regarding rWG,r*WG,rWG(j)r*WG(J). Organizational Research Methods 8, 128–138.

Markus, H.R., Kitayama, S., 1991. Culture and the self. Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychological Review 98 (21), 224–253. Mischel, W., 1968. Personality and Assessment. Wiley, New York, NY.

Moorman, R.H., Blakely, G.L., 1995. Individualism–collectivism as an individual difference predictor of organizational citizenship behavior. Journal of Organizational Behavior 16, 127–142.

Morgeson, F.P., Hofmann, D.A., 1999. The structure and function of collective constructs: implications for multilevel research and theory development. Academy of Management Review 24, 249–265.

Mowday, R.T., Sutton, R.I., 1993. Organizational behavior: linking individuals and groups to organizational contexts. Annual Review of Psychology 44, 195–229 National Human Development Report.

Nielsen, T.M., Hrivnak, G.A., Shaw, M., 2009. Organizational citizenship behavior and performance: a meta-analysis of group-level research. Small Group Research 40, 555–577.

Nunnaly, J., 1978. Psychometric Theory. McGraw-Hill, New York.

Organ, D.W., 1997. Organizational citizenship behavior: it's construct clean-up time. Human Performance 10, 85–97.

Paine, J.B., Organ, D.W., 2000. The cultural matrix of organizational citizenship behavior: some preliminary conceptual and empirical observations. Human Resource Management Review 10, 45–59.

Pearce, C.L., Herbik, P.A., 2004. Citizenship behavior at the team level of analysis: the effects of team leadership, team commitment, perceived team support, and team size. The Journal of Social Psychology 144 (3), 293–310.

Podsakoff, P.M., Mackenzie, S.B., 1994. Organizational citizenship behaviour and sales unit effectiveness. Journal of Marketing Research 31, 351–363. Podsakoff, P.M., Mackenzie, S.B., Paine, J.B., Bachrach, D.G., 2000. Organizational citizenship behavior: critical review of the theoretical and empirical literature and

suggestions for future research. Journal of Management 26, 513–563.

Ramamoorthy, N., Flood, P.C., 2004. Individualism/collectivism, perceived task interdependence and teamwork attitudes among Irish blue-collar employees: a test of the main and moderating effects. Human Relations 57, 347–366.

Robertson, C.J., Al-Khatib, J.A., Al-Habib, M., 2002. The relationship between Arab values and work beliefs: an exploratory examination. Thunderbird International Business Review 44 (5), 583–601.

Rousseau, D.M., Fried, Y., 2001. Location, location, location: contextualizing organizational research. Journal of Organizational Behavior 22, 1–13. Salancik, G.R., Pfeffer, J., 1978. A social information processing approach to job attitudes and task design. Administrative Science Quarterly 23, 224–253. Salibi, K., 1993. A House of Many Mansions: The History of Lebanon Reconsidered. I. B. Tauris, London.

Schneider, B., 1985. Interactional psychology and organizational behavior. In: Staw, B.M., Cummings, L.L. (Eds.), Research in Organizational Behavior. JAI Press, Greenwich, CT, pp. 1–37.

Sidani, Y., 2005. Women, work, and Islam in Arab societies. Women in Management Review 20 (7), 498–512.

Singelis, T.M., Triandis, H.C., Bhawuk, D.P.S., Gelfand, M.J., 1995. Horizontal and vertical dimensions of individualism and collectivism: a theoretical and measurement refinement. Cross-Cultural Research 29, 240–275.

Triandis, H.C., 1989. The self and social behavior in differing cultural contexts. Psychological Review 96, 506–520. Triandis, H.C., 1996. Individuals and Collectivism. New York McGraw Hill, New York.

Triandis, H.C., Bhawuk, D.P.S., 1997. Culture theory and the meaning of relatedness. In: Earley, P.C., Erez, M. (Eds.), New Perspectives on International Industrial/ Organizational Psychology. The New Lexington Free Press, New York, NY, pp. 13–52.

Triandis, H.C., Bontempo, R., Villareal, M.J., Asai, M., Lucca, N., Piedras, R., 1988. Individualism and collectivism: cross-cultural perspectives on self-ingroup relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 54, 323–338.

Triandis, H.C., Gelfand, M., 1998. Converging measurement of horizontal and vertical individualism and collectivism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 74, 118–128. Tsui, A.S., 2004. Contributing to global management knowledge: a case for high quality indigenous research. Asia Pacific Journal of Management 21, 491–513. UN, United Nations, 2005. World population prospects: the 2005 revision. Retrieved July 2, 2007, from the Population Division of the Department of Economic and

Social Affairs of the United Nations Secretariat Website:http://esa.un.org/unpp.

UNDP, United Nations Development Program, CDR, Council for Development and Reconstruction, 2009. The National Human Development Reports of Lebanon: Toward a Citizen State. Beirut, Lebanon.

Van Dyne, L., Cummings, L.L., McLean Parks, J., 1995. Extra-role behaviors: in pursuit of construct and definitional clarity. In: Cummings, L.L., Staw, B.M. (Eds.), Research in Organizational Behavior, pp. 215–285. 17.

Van Dyne, L., Vandewalle, D., Kostova, T., Latham, M.E., Cummings, L.L., 2000. Collectivism, propensity to trust and self-esteem: predictors of organizational citizenship behaviors in a non-work setting. Journal of Organizational Behavior 21, 3–23.