ETHICS

The Routledge Companion to Ethicsis an outstanding survey of the whole field of

ethics by a distinguished international team of contributors. Over 60 entries are divided into six clear sections:

The history of ethics Meta-ethics

Perspectives from outside ethics Ethical perspectives

Morality

Debates in ethics.

The Companion opens with a comprehensive historical overview of ethics, including entries on Plato, Aristotle, Hume and Kant, and the origins of ethical thinking in China, India and the Middle East. The second part covers the domain of meta-ethics, including entries on cognitivism and non-cognitivism, explanation, reasons, moral realism and fictionalism. The third part covers

important challenges to ethics from the fields of anthropology, psychology,

sociobiology and economics. The fourth andfifth sections cover competing

the-ories of ethics and the nature of morality respectively, with entries on con-sequentialism, Kantian morality, virtue ethics, relativism, morality and character, evil, responsibility and particularism in ethics among many others. A compre-hensive final section includes entries on the most important topics and

con-troversies in applied ethics, including rights, justice and distribution, the end of life, the environment, poverty, war and terrorism.

The Routledge Companion to Ethicsis a superb resource for anyone interested in the subject, whether in philosophy or related subjects such as politics, education, or law. Fully indexed and cross-referenced, with helpful further reading sections, it is ideal for those coming to the field of ethics for the first time as well as

readers already familiar with the subject.

ROUTLEDGE PHILOSOPHY

COMPANIONS

Routledge Philosophy Companionsoffer thorough, high quality surveys and

assess-ments of the major topics and periods in philosophy. Covering key problems, themes and thinkers, all entries are specially commissioned for each volume and written by leading scholars in thefield. Clear, accessible and carefully edited and

organized, Routledge Philosophy Companionsare indispensable for anyone coming to a major topic or period in philosophy, as well as for the more advanced reader.

The Routledge Companion to Aesthetics, Second Edition Edited by Berys Gaut and Dominic Lopes

The Routledge Companion to Ethics Edited by John Skorupski

The Routledge Companion to Philosophy of Religion Edited by Chad Meister and Paul Copan

The Routledge Companion to the Philosophy of Science Edited by Stathis Psillos and Martin Curd

The Routledge Companion to Twentieth Century Philosophy Edited by Dermot Moran

The Routledge Companion to Philosophy and Film Edited by Paisley Livingston and Carl Plantinga

The Routledge Companion to Philosophy of Psychology Edited by John Symons and Paco Calvo

The Routledge Companion to Metaphysics

Edited by Robin Le Poidevin, Peter Simons, Andrew McGonigal, and Ross Cameron

The Routledge Companion to Philosophy and Music Edited by Andrew Kania and Theodore Gracyk

The Routledge Companion to Epistemology Edited by Sven Bernecker and Duncan Pritchard

The Routledge Companion to Seventeenth Century Philosophy Edited by Dan Kaufman

The Routledge Companion to Eighteenth Century Philosophy Edited by Aaron Garrett

The Routledge Companion to Phenomenology Edited by Søren Overgaard and Sebastian Luft

The Routledge Companion to Philosophy of Mental Disorder Edited by Jakob Hohwy and Philip Gerrans

The Routledge Companion to Social and Political Philosophy Edited by Gerald Gaus and Fred D’Agostino

The Routledge Companion to Philosophy of Language Edited by Gillian Russell and Delia GraffFara

The Routledge Companion to Theism

Edited by Charles Taliaferro, Victoria Harrison, and Stewart Goetz

The Routledge Companion to Philosophy of Law Edited by Andrei Marmor

The Routledge Companion to Islamic Philosophy

PRAISE FOR THE SERIES

The Routledge Companion to Aesthetics

“This is an immensely useful book that belongs in every college library and on the bookshelves of all serious students of aesthetics.” –Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism

“The succinctness and clarity of the essays will make this a source that individuals not familiar with aesthetics will find extremely helpful.” – The Philosophical Quarterly

“An outstanding resource in aesthetics…this text will not only serve as a handy reference source for students and faculty alike, but it could also be used as a text for a course in the philosophy of art.” –Australasian Journal of Philosophy

“Attests to the richness of modern aesthetics … the essays in central topics – many of which are written by well-knownfigures–succeed in being informative, balanced and intelligent without being too difficult.” – British Journal of Aesthetics

“This handsome reference volume…belongs in every library.”–Choice

“The Routledge Companions to Philosophy have proved to be a useful series of high quality surveys of major philosophical topics and this volume is worthy enough to sit with the others on a reference library shelf.” – Philosophy and Religion

The Routledge Companion to Philosophy of Religion

“ …a very valuable resource for libraries and serious scholars.”–Choice

“With a distinguished list of internationally renowned contributors, an excellent choice of topics in thefield, and well-written, well-edited essays throughout, this

compendium is an excellent resource. Highly recommended.”–Choice

“Highly recommended for history of science and philosophy collections.” –

Library Journal

“This well conceived companion, which brings together an impressive collection of distinguished authors, will be invaluable to novices and experience readers alike.” –Metascience

The Routledge Companion to Twentieth Century Philosophy

“To describe this volume as ambitious would be a serious understatement. … full of scholarly rigor, including detailed notes and bibliographies of interest to professional philosophers.…Summing up: Essential.” –Choice

The Routledge Companion to Philosophy and Film

“A fascinating, rich volume offering dazzling insights and incisive commentary

on every page…Every serious student of film will want this book…Summing Up: Highly recommended.”–Choice

The Routledge Companion to Metaphysics

TO ETHICS

First edition published 2010 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 4RN Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge

270 Madison Ave, New York, NY 10016

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

© 2010 John Skorupski for selection and editorial matter; individual contributors for their contributions

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

The Routledge companion to ethics / edited by John Skorupski. p. cm.–(Routledge philosophy companions)

Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. Ethics. I. Skorupski, John, 1946–

BJ21.R68 2010

170–dc22 2009050204

Hbk ISBN 13: 978-0-415-41362-6 Ebk ISBN 13: 978-0-203-85070-1

This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2010.

To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledge’s collection of thousands of eBooks please go to www.eBookstore.tandf.co.uk.

CONTENTS

List of illustrations xv

Notes on contributors xvi

Preface xxv

PART I

History 1

1 Ethical thought in China 3

YANG XIAO

2 Ethical thought in India 21

STEPHEN R. L. CLARK

3 Socrates and Plato 31

RICHARD KRAUT

4 Aristotle 41

CHRISTOPHER TAYLOR

5 Later ancient ethics 52

A. A. LONG

6 The Arabic tradition 63

PETER ADAMSON

7 Early modern natural law 76

KNUD HAAKONSSEN

8 Hobbes 88

BERNARD GERT

9 Ethics and reason 99

MICHAEL LEBUFFE

10 Ethics and sentiment: Shaftesbury and Hutcheson 111 MICHAEL B. GILL

11 Hume 122

12 Adam Smith 133 CRAIG SMITH

13 Utilitarianism to Bentham 144

FREDERICK ROSEN

14 Kant 156

THOMAS E. HILL JR

15 Hegel 168

KENNETH R. WESTPHAL

16 John Stuart Mill 181

HENRY WEST

17 Sidgwick, Green, and Bradley 192

T. H. IRWIN

18 Nietzsche 204

MAUDEMARIE CLARK

19 Pragmatist moral philosophy 217

ALAN J. RYAN

20 Existentialism 230

JONATHAN WEBBER

21 Heidegger 241

STEPHEN MULHALL

PART II

Meta-ethics 251

22 Ethics, science, and religion 253

SIMON BLACKBURN

23 Freedom and responsibility 263

RANDOLPH CLARKE

24 Reasons for action 275

ROBERT AUDI

CONTENTS

25 The open question argument 286 THOMAS BALDWIN

26 Realism and its alternatives 297

PETER RAILTON

27 Non-cognitivism 321

ALEXANDER MILLER

28 Error theory andfictionalism 335

NADEEM J. Z. HUSSAIN

29 Cognitivism without realism 346

ANDREW FISHER

30 Relativism 356

NICHOLAS L. STURGEON

PART III

Ideas and methods from outside ethics 367

31 Social anthropology 369

JAMES LAIDLAW

32 Ethics and psychology 384

JESSE PRINZ

33 Biology 397

MICHAEL RUSE

34 Formal methods in ethics 408

ERIK CARLSON

35 Ethics and law 420

JOHN GARDNER

PART IV

Perspectives in ethics 431

36 Reasons, values, and morality 433

37 Consequentialism 444 BRAD HOOKER

38 Contemporary Kantian ethics 456

ANDREWS REATH

39 Ethical intuitionism 467

PHILIP STRATTON-LAKE

40 Virtue ethics 478

MICHAEL SLOTE

41 Contractualism 490

RAHUL KUMAR

42 Contemporary natural law theory 501

ANTHONY J. LISSKA

43 Feminist ethics 514

SAMANTHA BRENNAN

44 Ethics and aesthetics 525

ROBERT STECKER

PART V

Morality 537

45 Morality and its critics 539

STEPHEN DARWALL

46 Conscience 550

JOHN SKORUPSKI

47 Respect and recognition 562

ALLEN W. WOOD

48 Blame, remorse, mercy, forgiveness 573

CHRISTOPHER BENNETT

49 Evil 584

GEOFFREY SCARRE

CONTENTS

50 Responsibility: Intention and consequence 596 SUZANNE UNIACKE

51 Responsibility: Act and omission 607

MICHAEL J. ZIMMERMAN

52 Partiality and impartiality 617

JOHN COTTINGHAM

53 Moral particularism 628

MICHAEL RIDGE AND SEAN MCKEEVER

PART VI

Debates in ethics 641 (i) Goals and ideals

54 Welfare 645

CHRISTOPHER HEATHWOOD

55 Ideals of perfection 656

VINIT HAKSAR

(ii) Justice

56 Rights 669

TOM CAMPBELL

57 Justice and punishment 680

JOHN TASIOULAS

58 Justice and distribution 692

MATTHEW CLAYTON

(iii) Human life

59 Life, death, and ethics 707

FRED FELDMAN

60 Ending life 720

R. G. FREY

(iv) Our world

61 Population ethics 731

62 Animals 742 ALAN CARTER

63 The environment 754

ANDREW BRENNAN AND NORVA Y. S. LO

(v) Current issues

64 The ethics of free speech 769

MARY KATE MCGOWAN

65 The ethics of research 781

JULIAN SAVULESCU AND TONY HOPE

66 World poverty 796

THOMAS POGGE

67 War 808

HENRY SHUE

68 Torture and terrorism 820

DAVID RODIN

Index 832

CONTENTS

ILLUSTRATIONS

Figures

26.1 Branching taxonomy of meta-ethical positions with respect to

questions of realism. 303

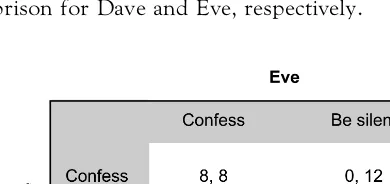

34.1 A prisoner’s dilemma matrix (severity of harms to agents caused by

alternative choices). 414

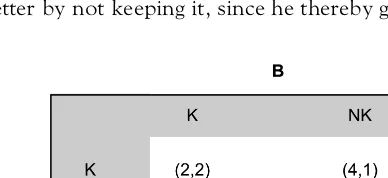

45.1 Values of the outcomes of A’s and B’s choices in a prisoner’s

dilemma. 543

Tables

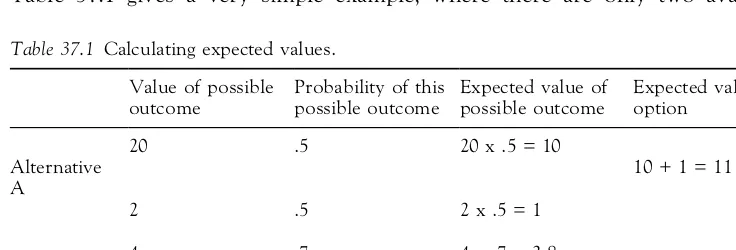

37.1 Calculating expected values. 450

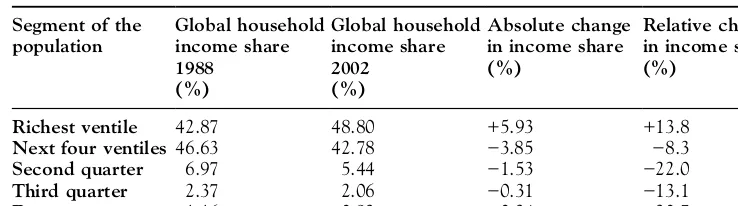

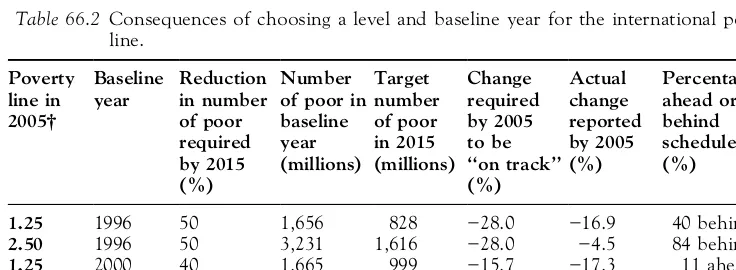

66.1 Distribution of global household income converted at current market

exchange rates. 798

66.2 Consequences of choosing a level and baseline year for the

CONTRIBUTORS

Peter Adamson is Reader of Philosophy at King’s College London. His main areas of interest are ancient philosophy (especially Neoplatonism) and medie-val philosophy (especially in Arabic). He is the author ofThe Arabic Plotinus, and has published articles on Plotinus, al-Kindi, al-Farabi, Avicenna and other

figures from Greek and Arabic philosophy.

Robert Audi is Professor of Philosophy and David E. Gallo Chair in Ethics, University of Notre Dame. He writes on epistemology, philosophy of action and philosophy of religion as well as on moral and political philosophy. His recent books include Religious Commitment and Secular Reason (2000), The Architecture of Reason (2001), The Good in the Right: A Theory of Intuition and Intrinsic Value (2004), Practical Reasoning and Ethical Decision (Routledge, 2006), and (as editor)The Cambridge Dictionary of Philosophy(1995, 1999).

Thomas Baldwinis a Professor of Philosophy at the University of York, having been previously a lecturer in philosophy at Cambridge University. He is cur-rently editor ofMind.

Christopher Bennett is a lecturer in the Department of Philosophy, University of Sheffield. His work has mainly concerned the moral emotions, punishment

and criminal justice.

Simon Blackburn is Professor of Philosophy at the University of Cambridge, and Research Professor at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. His books include: Spreading the Word (1984), Essays in Quasi-Realism (1993), The Oxford Dictionary of Philosophy (1994), Ruling Passions (1998), Think (1999), Being Good (2001), Lust (2004), Truth: A Guide (2005), Plato’s Republic (2006)

andHow to Read Hume(2008).

Andrew Brennan is Professor and Chair of Philosophy at La Trobe University, Melbourne, Australia, having previously been Professor and Chair of Philo-sophy at the University of Western Australia and Reader in PhiloPhilo-sophy at the University of Stirling, Scotland.

Tom Campbell is Professor Fellow at Charles Sturt University and Convenor of the Centre for Applied Philosophy and Public Ethics, an Australian Research Council Special Research Centre. He has written extensively on law and legal philosophy. He is author of Adam Smith’s Science of Morals

(1971), The Left and Rights (1983) and Justice (1988, 2nd edn forthcoming in 2010). His Routledge book, Rights: A Critical Introduction, was published in 2006.

Erik Carlson is Professor of Practical Philosophy at Uppsala University. His areas of research include axiology, measurement theory, normative ethics, the problems of free will and determinism, and decision theory. He has published one book, Consequentialism Reconsidered (1995), and about thirty papers in journals and anthologies.

Alan Carteris Professor of Moral Philosophy at the University of Glasgow. He is the author of numerous articles and three books:A Radical Green Political Theory, The Philosophical Foundation of Property Rights and Marx: A Radical Critique. He is also joint editor of theJournal of Applied Philosophy.

Maudemarie Clark is Professor of Philosophy at the University of California– Riverside. She is the author of Nietzsche on Truth and Philosophy (1990), co-translator and -editor of Nietzsche’s On the Genealogy of Morality (1998), and co-author of a work in progress on Nietzsche’sBeyond Good and Evil.

Stephen R. L. Clarkis Professor of Philosophy at the University of Liverpool. His most recent book is G. K. Chesterton: Thinking Backward, Looking Forward (2006), and his present work deals with the third-century Neoplatonist, Plotinus.

Randolph Clarke is Professor of Philosophy at Florida State University. He is the author of Libertarian Accounts of Free Will and of numerous articles on agency, free will and moral responsibility.

Matthew Claytonis Associate Professor of Political Theory at the University of Warwick. He works on issues concerning distributive justice and liberal poli-tical thought. His recent work includes Justice and Legitimacy in Upbringing (2006) and he has co-edited The Ideal of Equality (2002) and Social Justice (2004).

Stephen Darwallis the Andrew Downey Orrick Professor of Philosophy at Yale University. He has written broadly on the history and foundations of ethics. His books include Impartial Reason, The British Moralists and the Internal

“Ought,”Philosophical Ethics,Welfare and Rational Careand most recentlyThe

Second-Person Standpoint: Morality, Respect, and Accountability. With David Velleman, he is a founding co-editor ofThe Philosophers’ Imprint.

Fred Feldman, University of Massachusetts at Amherst. Author of Introductory Ethics(1978),Doing the Best We Can: An Essay in Informal Deontic Logic(1986), Confrontations with the Reaper: A Philosophical Study of the Nature and Value of Death (1992), and Pleasure and the Good Life: On the Nature, Varieties, and Plausibility of Hedonism(2004).

Andrew Fisheris Lecturer in Philosophy at the University of Nottingham. His research is primarily in meta-ethics and he has published in this area. He teaches a large number of students on a wide range of subjects including meta-ethics. He is co-editor with Simon Kirchin ofArguing about Metaethics(Routledge, 2006).

R. G. Frey is Professor of Philosophy at Bowling Green State University and Senior Research Fellow in the Social Philosophy and Policy Center there. He is the author (and editor) of numerous books and articles in normative and applied ethics.

John Gardneris Professor of Jurisprudence and a Fellow of University College, Oxford. An occasional Visiting Professor at Yale Law School and a Bencher of the Inner Temple, he was formerly Reader in Legal Philosophy at King’s College London (1996–2000). He serves on the editorial boards of theOxford Journal of Legal Studies,Legal Theory,Law and Philosophy,The Journal of Moral Philosophy, The Journal of Ethics and Social Philosophy, The Journal of Inter-national Criminal Justice andCriminal Law and Philosophy.

Bernard Gertis Stone Professor of Intellectual and Moral Philosophy, Emeritus, Dartmouth College. He is the author of Morality: Its Nature and Justification (revised edn, 2005),Common Morality: Deciding What to Do(2004) andHobbes: Prince of Peace (2010); first author of Bioethics: A Systematic Approach (2006),

and editor ofMan and Citizen (1972, 1991).

Michael B. Gill is Associate Professor of Philosophy at the University of Arizona. He received his PhD from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and is the author ofThe British Moralists on Human Nature and the Birth of Secular Ethics (2006). He has also published numerous articles in the history of philosophy, meta-ethical theory and medical ethics.

Knud Haakonssen is Professor of Intellectual History and Director of the Sussex Centre for Intellectual History, University of Sussex. He has published extensively on early modern moral, legal and political philosophy and edits a large series of natural law works.

CONTRIBUTORS

Vinit Haksar is a Fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh and an Honorary Fellow, School of Philosophy, Psychology and Language Sciences, University of Edinburgh. His publications include Equality, Liberty and Perfectionism (1979), Indivisible Selves and Moral Practice (1991) and Rights, Communities and Disobedience: Liberalism and Gandhi(2003).

James A. Harris is Senior Lecturer in Philosophy at the University of St Andrews. He is the author ofOf Liberty and Necessity: The Free Will Debate in Eighteenth-Century British Philosophy(2005). He is the editor of the forthcoming Oxford Handbook of British Philosophy in the Eighteenth Century, and (with Aaron Garrett) of the “Enlightenment” volume of A History of Scottish Philosophy (general editor Gordon Graham).

Christopher Heathwood is Assistant Professor of Philosophy at the University of Colorado at Boulder. He is the author of several articles on welfare and other topics in ethics.

Thomas E. Hill Jr, Kenan Professor at University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, is the author ofAutonomy and Self-Respect;Dignity and Practical Reason in Kant’s Moral Theory; Respect, Pluralism, and Justice; and Human Welfare and Moral Worth. He edited the Blackwell Guide to Kant’s Ethics and, with Arnulf

Zweig, co-edited Kant’s Groundwork for the Metaphysics of Morals. Recent essays concern Kantian constructivism, duties to oneself, virtue, revolution, humanitarian interventions, and the treatment of criminals.

Brad Hooker is Professor of Moral Philosophy at the University of Reading. His book Ideal Code, Real World: A Rule-Consequentialist Theory of Morality appeared in 2000. He has published articles on intuitionism, Kantianism, particularism, human rights, desert, world hunger, impartiality, the demand-ingness of morality and friendship. His research monograph will be on fairness.

Tony Hope is Professor of Medical Ethics at the University of Oxford, Hon-orary Consultant Psychiatrist, and Fellow of St Cross College. He founded the Ethox Centre. He has carried out research in basic neuroscience, Alzheimer’s disease and clinical ethics. His books include the Oxford Handbook of Clinical Medicine (editions 1–4); Manage Your Mind; Medical Ethics and Law; Medical Ethics: A Very Short Introduction; andEmpirical Ethics in Psychiatry.

Nadeem J. Z. Hussain is an Associate Professor of Philosophy at Stanford University. He specializes in meta-ethics and the history of late nineteenth-century German philosophy. He assessed the resurgence of fictionalism in

T. H. Irwinis Professor of Ancient Philosophy in the University of Oxford and a Fellow of Keble College. From 1975 to 2006 he taught at Cornell University. He is the author of Plato’s Gorgias (translation and notes 1979), Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics (translation and notes 1999), Aristotle’s First Principles

(1988), Classical Thought (1989), Plato’s Ethics (1995) and The Development of Ethics, 3 vols (2007–9).

Richard Kraut is the Charles E. and Emma H. Morrison Professor in the Humanities at Northwestern University. He is the author of Socrates and the State andHow to Read Plato, and has editedthe Cambridge Companion to Plato andPlato’s Republic: Critical Essays.

Rahul Kumar is an Associate Professor of Philosophy at Queen’s University, Canada. He is a co-editor of Reasons and Recognition: Essays on the Philosophy of T. M. Scanlon and is the author of several papers on Scanlonian contractualism.

James Laidlaw is a Fellow of King’s College, Cambridge, and a University Le cturer in the Department of Social Anthropology, University of Cambridge. He has conducted research in India, Inner Mongolia and Taiwan. His publications include Riches and Renunciation (1995); a two-volume collection of the writings of the social anthropologist Edmund Leach, The Essential Edmund Leach (2001); and two collections, both jointly edited with Harvey Whitehouse: Ritual and Memory (2004) and Religion, Anthropology, and Cogni-tive Science(2007).

Michael LeBuffe is Assistant Professor at Texas A&M University. His recent work includes“Spinoza’s Normative Ethics,”inCanadian Journal of Philosophy (2007), and “The Anatomy of the Passions,” in the Cambridge Companion to Spinoza’s Ethics (forthcoming).

Anthony J. Lisska, Maria Theresa Barney Professor of Philosophy at Deni-son University, has publishedAquinas’s Theory of Natural Lawand essays and reviews on natural law. Past President of the American Catholic Philoso-phical Association, he received the Carnegie National Professor of the Year award.

A. A. Long is Professor of Classics, Irving Stone Professor of Literature, and affiliated Professor of Philosophy at the University of California, Berkeley. He

is author and editor of many books on ancient philosophy, including most recently Epictetus: A Stoic and Socratic Guide to Life and From Epicurus to Epictetus: Studies in Hellenistic and Roman Philosophy.

Norva Y. S. Lo is Lecturer in Philosophy at La Trobe University, Melbourne, Australia, having previously worked at the University of Hong Kong and the Chinese University of Hong Kong.

CONTRIBUTORS

Mary Kate McGowan is Class of 1966 Associate Professor of Philosophy at Wellesley College. She has published in metaphysics, philosophy of language, philosophy of law and analytic feminism and she is especially interested in free speech issues in their intersection.

Sean McKeever is Assistant Professor of Philosophy at Davidson College, North Carolina. He is interested in contemporary moral theory, the history of ethics and political philosophy. He is the author, with Michael Ridge, of Principled Ethics: Generalism as a Regulative Ideal (2006), which critiques moral particularism while developing and defending a generalist alternative.

Alexander Miller is Professor of Philosophy at the University of Birmingham. He is the author ofAn Introduction to Contemporary Metaethics (2003), Philoso-phy of Language (Routledge, 2nd edn 2007) and co-editor (with Crispin Wright) ofRule-Following and Meaning(2002).

Tim Mulgan is Professor of Moral and Political Philosophy at the University of St Andrews. He is the author of The Demands of Consequentialism (2001), Future People (2006) andUnderstanding Utilitarianism (2007).

Stephen Mulhallis Professor of Philosophy at New College, Oxford. His current areas of research include Nietzsche, Sartre, Heidegger and Wittgenstein, the philosophy of religion, and philosophy of literature. Recent publications include The Wounded Animal: J. M. Coetzee and the Difficulty of Reality in Literature and Philosophy (2009) andThe Conversation of Humanity(2007).

Thomas Pogge received his PhD from Harvard. He is Leitner Professor of Philosophy and International Affairs at Yale University, Professorial Fellow at

the Australian National University’s Centre for Applied Philosophy and Public Ethics, Research Director at the Oslo University Centre for the Study of Mind in Nature, and Adjunct Professor at the Faculty of Health and Social Care of the University of Central Lancashire.

Jesse Prinz is Distinguished Professor of Philosophy at the City University of New York Graduate Center. His research areas are philosophy of psychology, philosophy of mind, aesthetics, consciousness and cognitive science. His books include The Emotional Construction of Morals (2007), Gut Reactions: A Perceptual Theory of Emotion(2004) and Furnishing the Mind: Concepts and Their Perceptual Basis (2002).

Andrews Reath is Professor of Philosophy at the University of California, Riverside. He has worked extensively on Kant’s moral philosophy and is author of Agency and Autonomy in Kant’s Moral Theory (2006). He has co-edited two anthologies: with Barbara Herman and Christine Korsgaard, Reclaiming the History of Ethics: Essays for John Rawls (1997); and with Jens Timmermann, A Critical Guide to Kant’s Critique of Practical Reason (2010).

Michael Ridgeis Professor of Moral Philosophy at the University of Edinburgh. His main research is in moral and political philosophy, though he also has substantial research interests in action theory, the philosophy of mind and the history of philosophy. He is the author, with Sean McKeever, of Principled Ethics: Generalism as a Regulative Ideal(2006).

Simon Robertson is a Postdoctoral Research Fellow working on the Nietzsche and Modern Moral Philosophy project at the University of Southampton. His main research interests lie at the intersection of normative ethics, meta-ethics and practical reason.

David Rodin is Senior Research Fellow at the University of Oxford, where he co-directs the Oxford Institute for Ethics, Law and Armed Conflict, and

Senior Fellow at the Carnegie Council for Ethic and International Affairs in

New York. His publications include War and Self-Defense (2002), which was awarded the American Philosophical Association Sharp Prize, as well as of articles in leading philosophy and law journals and a number of edited books, includingPreemption(2007) andJust and Unjust Warriors(2008).

Frederick Rosenis Professor Emeritus of the History of Political Thought and Honorary Research Fellow at the Bentham Project, University College London. He was formerly Director of the Bentham Project and General Editor of The Collected Works of Jeremy Bentham. He is currently writing a book on the moral and political philosophy of John Stuart Mill.

Michael Ruseis Lucyle T. Werkmeister Professor of Philosophy at Florida State University. He is the author of many books on the history and philosophy of science, including Monad to Man: The Concept of Progress in Evolutionary Biology, Can a Darwinian be a Christian? The Relationship between Science and Religion and most recently Science and Spirituality: Making Room for Faith in the Age of Science.

Alan J. Ryan was Warden of New College, Oxford, from 1996 to 2009. He is currently a Visiting Scholar at Princeton University. Professor Ryan has written extensively on liberalism and its history, on theories of property, and on issues in the philosophy of the social sciences; among his books areLiberal Anxieties and Liberal Education (1998), John Dewey and the High Tide of American Liberalism(1995) andRussell: A Political Life(2003).

CONTRIBUTORS

Julian Savulescu is Uehiro Chair in Practical Ethics and Director of the Oxford Uehiro Centre for Practical Ethics at the University of Oxford. He is also Director of the Oxford Centre for Neuroethics and of the Program on the Ethics of the New Biosciences at the University of Oxford. Professor Savulescu is the author of over 200 publications and has given more than 100 international presentations.

Geoffrey Scarreis Professor of Philosophy at Durham University, UK, where he teaches and researches mainly in the areas of moral theory and applied ethics. He has recently published books on death and on Mill’sOn Liberty; his most recent book isOn Courage(Routledge, forthcoming in 2010).

Henry Shue is Senior Research Fellow at Merton College, Oxford, and Professor of Politics and International Relations. His research has focused on the role of human rights, especially economic rights, in international affairs,

and, more generally, on institutions to protect the vulnerable. He is best known for his book on international distributive justice,Basic Rights.

John Skorupski is Professor of Moral Philosophy at the University of St Andrews. His books include John Stuart Mill (Routledge, 1989), Ethical Explorations(1999) andThe Domain of Reasons (forthcoming in 2010).

Michael Slote is UST Professor of Ethics at the University of Miami. He has recently been working at the intersection of virtue ethics, care ethics and moral sentimentalist thought, and has just published three books: Moral Sen-timentalism (an account of normative ethics and meta-ethics in sentimentalist terms); Essays on the History of Ethics (containing discussions of both ancient and modern views); andSelected Essays (a collection of published articles and some new papers).

Craig Smith is Lecturer in Philosophy at the University of St Andrews. He is the author of Adam Smith’s Political Philosophy: The Invisible Hand and Spontaneous Order (Routledge, 2006), and is book review editor of the Adam Smith Review.

Robert Steckeris Professor of Philosophy at Central Michigan University. He is the author ofArtworks: Definition, Meaning, Value;Interpretation and Construction: Art, Speech and the Law; and Aesthetics and the Philosophy of Art: An Introduction.

Philip Stratton-Lake is Professor of Philosophy at the University of Reading. His main research interests are Kant, ethical intuitionism, meta-ethics and normative ethics. His book Kant, Duty and Moral Worth was published by Routledge in 2000.

John Tasioulas is Reader in Moral and Legal Philosophy at the University of Oxford and Fellow of Corpus Christi College, Oxford. His research interests are in moral philosophy, legal philosophy, and political philosophy. He is currently engaged in a project on the philosophy of human rights funded by a British Academic Research Development Award.

Christopher Taylor is Emeritus Professor of Philosophy, Oxford University, and an Emeritus Fellow of Corpus Christi College, Oxford.

Suzanne Uniacke is Reader in Applied Ethics at the University of Hull. Before moving to the United Kingdom in 2001 she taught philosophy in Australia. She has published widely in normative moral theory, applied ethics and phi-losophy of law.

Jonathan Webber is a lecturer in Philosophy at Cardiff University. He is the

author of The Existentialism of Jean-Paul Sartre (Routledge, 2009), and numer-ous philosophical articles on moral psychology and applied ethics.

Henry R. West is Professor of Philosophy at Macalester College, Saint Paul, Minnesota. His publications on Mill includeAn Introduction to Mill’s Utilitarian

Ethics (2004), The Blackwell Guide to Mill’s Utilitarianism (2006) and Mill’s Utilitarianism:A Reader’s Guide(2007).

Kenneth R. Westphal is Professor of Philosophy at the University of Kent, Canterbury. He has published widely on both Kant’s and Hegel’s theoretical and practical philosophies, in both systematic and historical perspective. He editedThe Blackwell Guide to Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit(2009).

Allen W. Wood is Ward W. and Priscilla B. Woods Professor at Stanford University. He has also been on the faculty of Cornell University and Yale University, has held visiting appointments at the University of Michigan and the University of California, San Diego, and has held fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation and the National Endowment for the Humanities. He is author and editor of numerous books and author of numerous articles, chiefly on topics in ethics and on the philosophy of Kant, Fichte, Hegel and

Marx.

Yang Xiao is Associate Professor of Philosophy at Kenyon College, USA. He has published essays on Confucian moral psychology, philosophy of language in early Chinese texts and Chinese political philosophy. He is currently working on a book manuscript on early Chinese ethics.

Michael J. Zimmerman is Professor of Philosophy at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro. He is the author of both books and articles on the conceptual foundations of human action, moral responsibility, moral obligation and intrinsic value.

CONTRIBUTORS

PREFACE

A companion to ethics should be a companion for two kinds of inquirers. The

first consists, of course, of students and teachers of philosophy. The second

comprises a much wider group–anyone who is interested in the state of philo-sophical ethics today, and the history of how we got to where we are.

Philosophical ethics is only a small part of the general ethical discussion that goes on in any society at any time. However, it can and should make a vital contribution to that wider discussion. Furthermore this is especially true in the case of ethics, for various reasons that do not apply, or do not apply as much, to other parts of philosophy. To be sure, some cogent philosophical questions about ethics are quite abstract, and cannot so easily be made accessible to wider ethical discussion. Philosophy does, after all, have an obligation to follow wher-ever its questions lead. A comprehensive companion to ethics should try to convey what is currently being said about such questions. Yet it should also, as one of its main aims, engage with the wider discussion, and be as helpful as possible to anyone seriously interested in ethical questions – across all their width and depth. In designing the structure and content of this Companion we have tried hard to keep these aims in mind.

I should mention that we have in the end been unable to obtain two chapters that we would very much like to have had: in Part I, on medieval ethics, and in Part VI, on ethical questions about the beginning of life. We regret this and hope to include chapters on these topics in future editions.

My personal thanks must go in the first place to our authors, for their

patience and diligence. Apart from anything else, I have learnt an enormous amount about ethics and its history from their work. Tony Bruce at Routledge suggested the idea of a Companion to Ethics to me, and has been truly helpful and encouraging throughout. I am also very grateful to Adam Johnson and James Thomas for their editorial efficiency and hard work. Finally, my thanks to Roger

1

ETHICAL THOUGHT

IN CHINA

Yang Xiao

Chinese ethical thought has a long history; it goes back to the time of Confucius (551–479BCE), which was around the time of Socrates (469–399 BCE). In a brief chapter like this, it is obviously impossible to do justice to the richness, com-plexity, and heterogeneity of such a long tradition. Instead of trying to cover all the aspects of it, I focus on the early period (551–221BCE), which is the founding era of Chinese philosophy. More specifically, I focus on the four main schools

of thought and their founding texts: Confucianism (the Analects, the Mencius, and the Xunzi), Mohism (the Mozi), Daoism (the Daodejing and the Zhuangzi), and Legalism (the Book of Lord Shang). There are two reasons for this choice. First, Chinese philosophers from later periods often had to present their own thoughts in the guise of commentaries on these founding texts; they spoke about them as well as through them. Second, this choice reflects the fact that early

China is still the most scrutinized period of the history of Chinese philosophy by scholars in the English-speaking world, and that most of the important texts from this period have been translated into English.

It must be borne in mind that the early period lasted for about 300 years, which may still be too long for such a brief chapter to cover. My goal is not to provide an encyclopedic coverage or standard chronological account of ethical thought in early China. Rather, I want to identify important and revealing common features and themes of the content, style, and structure of ethical thought in this period that have reverberated throughout the history of Chinese philosophy, and have uniquely defined and characterized the tradition as a

whole. In other words, this will not be a historian’s, but rather a philosopher’s, take on the history of Chinese ethical thought.

In this chapter I use terms such as“Chinese philosophy,” “Chinese philosophers,” and “Chinese ethics,” which some scholars may find problematic. There has

Confucius is not a“philosopher of ethics”and has no“normative ethical theory” (Hansen 1992). This is obviously a complicated issue. The reality is that in China we canfind both normative ethicaltheoryand ethicalpracticessuch as

self-cultivation through spiritual exercise. In what follows, I first address the unique

problem of style in Chinese ethics; I then discuss the structure of the normative ethical theories of the four main schools of thought. I end with a discussion of the idea of philosophy as spiritual exercise, as well as a brief conclusion.

The problem of style in Chinese ethical thought

One main reason that Chinese philosophical texts are difficult to understand is

our unfamiliarity with their styles. For example, when a contemporary reader picks up a copy of the Analects, she might find it very easy to understand the

literal meaning of Confucius’ short, aphorism-like utterances; however, she might still be baffled because she does not know what Confucius is doing with

his utterances.

In his theory of interpretation, Davidson argues that an utterance always has at least three dimensions. Besides its “literal meaning,” which is given by a truth-conditional semantics, it also has its “force”(what the speaker is doing with it, whether the speaker intends it to be an assertion, a joke, a warning, an instruc-tion, and so on), as well as its“ulterior non-linguistic purpose”(why the speaker is saying what he says, what effects the speaker wants to have on what audience,

and so on) (Davidson 1984a, b, 1993). We may say that the literal meaning is the “content” of an utterance, and the force and purpose are the “style” of the utterance. This theory might help us understand that whenever we do not understand an early Chinese text it is often not because the author is an“oriental mystic,” but rather because we do not know enough about the historical back-ground to understand what the author is trying to do. We as scholars often misunderstand Chinese philosophers because of our projected expectations about what they must have been trying to accomplish; as Bernard Williams puts it,“a stylistic problem in the deepest sense of ‘style’ … is to discover what you are really trying to do”(Williams 1993: xviii–xix).

We now know a great deal about the historical background of early Chinese philosophy (Hsu 1965; Lewis 1990; Pines 2002; Lloyd and Sivin 2002; von Falkenhausen 2006); the most important aspect might be that the early philoso-phers were primarily trying to solve practical problems in the real world that seemed to be governed only by force and violence. To get a concrete sense of how extremely violent their time was, here are some revealing statistics. Con-fucius, the most important Confucian philosopher, lived around the end of the Spring and Autumn period (722–464 BCE); during the 258 years of the period, there were 1,219 wars, with only 38 peaceful years in between (Hsu 1965: 66). All of the other philosophers discussed in this chapter lived during the Warring

YANG XIAO

States period that lasted for 242 years (463–221 BCE), during which there had been 474 wars, and only 89 peaceful years (Hsu 1965: 64; also see Lewis 1990). Although there were fewer wars during the Warring States period, they were much longer and intense, and with much higher casualties. As we shall see, this fact has an important impact on how the early Chinese philosophers construct their ethical theories.

However, this turbulent time was also the golden years of early Chinese phi-losophy. Confucian philosophers such as Confucius, Mencius and Xunzi, the philosopher Mozi (the founder of Mohism), Daoist philosophers such as Laozi and Zhuangzi, and Legalist philosophers such as Shen Buhai, Shang Yang, Shen Dao, and Hanfeizi all lived through great political uncertainties and the brutalities of warfare, and their philosophies, especially their ethics, were profoundly shaped by this shared experience. We canfind passages in these thinkers’ work that show how they were traumatized by the wars and the sufferings of the people,

and it should not come as a surprise that almost all of them saw themselves as “political agents and social reformers” (von Falkenhausen 2006: 11). They tra-veled from state to state, seeking positions with rulers, such as political advisers, strategists, and, ideally, high-ranking officials. One of the central problems they

were obsessed with was the following: What must be done in order to bring peace, order, stability, and unity to the chaotic and violent world? Their solution to the practical problems of their time is a whole package, in which individual, familial, social, economic, political, legal, and moral factors were seamlessly interwoven. In fact, they did not have a distinction between ethics and politics, as we do today. They seemed to take for granted that questions about how one ought to act, feel, and live cannot be answered without addressing questions about what a good society ought to be like. This is why the terms“ethics”and“moral philosophy”should be understood in their broadest sense in this chapter, which includes“political philosophy”as well as“legal philosophy.”

The structure of Chinese ethical theories

There are various ways to characterize the structure of an ethical theory. It seems that one way to characterize Chinese ethical theories is to articulate at least three components:

(a) A part that deals with a theory of the good or teleology which indicates what goals or ends one ought to pursue, as well as ideals one ought to imitate or actualize (Skorupski 1999).

as the only normative factor to determine its moral status, one would be a “factoral consequentialist.”

(c) A part that gives justifications for its normative claims. It often involves a

theory of the good, a theory of agency and practical reasoning, or a theory of human nature. This part consists of the“foundation”of an ethical theory (Kagan 1998). It can be read as addressing what Christine Korsgaard calls the “normative question” (Korsgaard 1996). For instance, if one justifies a

policy (an action, an institution) by arguing that it is the best or necessary means to the realization of an ideal society, one would be a “foundational consequentialist.”

In the next four sections, I discuss the ethical theory of each of the four schools of thought according to the following sequence. First, I discuss (a) its theory of the good on the level of the state, as well as on the level of the individual. Second, I discuss (b) its account of normative factors. Third, I discuss (c) how it justifies its normative claims.

More specifically, when I discuss (b), I pay attention to two issues: First, how

it defines virtuous actions, whether it is “evaluational internalist” or “ evalua-tional externalist”(Driver 2001: 68)–that is, whether a virtuous action is defined

in terms of factors internal to the agent, such as belief, intention, desire, emo-tion, and disposition (hence an internalist), or in terms of factors external to the agent, such as the consequence (hence an externalist). We shall use“internalism” as a shorthand for “evaluational internalism” in the rest of this chapter; one should not confuse it with a very different view also labeled“internalism,”which can be found in the debate regarding whether reason for action must be internal or not. Second, I shall pay special attention to the issue of whether an ethical theory is “deontological” in the sense that it regards “constraints” (the moral barriers to the promotion of the good) as an evaluational factor (Kagan 1998).

Confucian ethical theory

Let us start with Confucianism (Schwartz 1985: 56–134, 255–320; Graham 1989: 9–33, 107–32, 235–67). The Confucians, most famously Confucius (551–479BCE) (Van Norden 2002), Mencius (385–312BCE) (Shun 1997; Liu and Ivanhoe 2002), and Xunzi (310–219BCE) (Klein and Ivanhoe 2000), have a theory of the good on the level of the state, as well as the level of the individual. With regard to the state, they believe that it is important for a state to have external goods, such as being orderly, prosperous, having an extensive territory, and a vast population. However, the Confucians believe that an ideal state must have“moral character” in the sense that the state should have no other end than the perfection of human relationships and the cultivation of virtues of the individual, and that the morality of the state must be the same as the morality of the individual. This is

YANG XIAO

arguably the most important feature of Confucian ethics, which the Legalists such as Hanfei would eventually reject by arguing that private and public mor-ality ought to be different, and that Confucian virtues could actually be public

vices. The Confucian ideal society that everyone ought to pursue should have at least the following moral characteristics:

(1) Every one follows social rules and rituals (li) that govern every aspect of life in the ideal society (Analects1.15, 6.27, 8.2, see Lau 1998;Xunzi10.13, see Knoblock 1988).

(2) Everyone in the ideal society has social roles and practical identities that come with special obligations; for instance, a son must havefilial piety (xiao)

towards his father (Analects1.2, 1.11, 2.5–8, 13.18, 17.21), an official must

have loyalty (zhong) towards his or her ruler (3.19), and a ruler must have ben-evolence (ren) towards his or her people (Mencius 1A4, 1A7, 1B5, see Lau 2005;Xunzi10.13). Ajunzi(virtuous person, or gentleman scholar-official) must

have a comprehensive set of virtues, such asren(humanity, benevolence, or empathy), yi (justice, righteousness),li (social rules and rituals internalized as deep dispositions), zhi(practical wisdom),xin(trust), yong(courage), and shu(reciprocity, or the golden rule internalized as a deep disposition). (3) “Benevolent politics”(ren-zheng) is practiced when the state adopts just and

benevolent policies regarding the distribution of external goods, as well as policies that may be characterized as“universal altruism”in the sense that a virtuous person cares about everyone in the world, including both those who are near and dear and those who are strangers, especially the weak and the poor (Mencius 1A4, 1A7, 1B5).

(4) “Virtue-based politics”is practiced when the ruler wins the allegiance and trust of the people not through laws or coercion, but through the trans-formative power of virtuous actions (Analects 2.1, 2.19, 2.20, 12.7, 12.17, 12.18, 12.19, 13.4, 13.6, 12.18, 14.41; Mencius2A3, 3A2, 4A20, 7A12–14). (5) The unification of the various states in China is not achieved through force

and violence, but through the transformative power of virtue (Mencius 2A3; 4B16, 7B13, 7B32;Xunzi9.9, 9.19a, 10.13, 18.2).

The central idea here is that it is not enough for a state to be strong and pros-perous; it must have moral character, such as justice and benevolence– virtues intimately connected with politics. I shall use the term“virtue politics”(de-zheng) in a broad sense to refer to the Confucian ethical-political program as a whole.

by the desire to obtain these external goods (Analects2.18, 15.32, 19.7, 15.32). In sharp contrast to external goods, “virtue,” “will,”and “true happiness” are not subject to luck, and are under the agent’s control (Analects7.30, 9.31, 9.26, 6.11). Virtuous persons take pleasure in doing virtuous actions, even when they live in poverty (Analects6.11).

In general, the Confucians are“internalists”in the sense that they define virtuous

actions in terms of factors internal to the agent, such as the agent’s intentions, motives, emotions, or deep dispositions, rather than defining them in terms of

factors external to the agent, such as external goods or consequences. Among all the Confucians, Mencius might be the most persistent advocate for an internalist definition of virtuous actions. For example, in Mencius, we find an “ expressi-vist”definition of benevolent actions, which is that an action is benevolent if it is

a natural and spontaneous expression of one’s deep dispositions of compassion for the people (Xiao 2006b). The deep disposition of compassion is what Mencius calls the“heart that cannot bear to see the suffering of others”(2A6):

The reason why I say that everyone has the heart that cannot bear to see the suffering of others is as follows. Suppose someone suddenly sees a child

who is about to fall into a well. Everyone in such a situation would have a feeling of empathy, and it is not because one wants to get in the good graces of the parents, nor because one wants to gain fame among one’s neigh-bors and friends, nor because one dislikes the sound of the child’s cry.

(Mencius2A6; see Lau 2005; translation modified)

Mencius believes that this “heart”is innate and universal, and it is what dis-tinguishes a human being from a non-human animal. One might argue that Mencius’ account of the virtue of benevolence is similar to Michael Slote’s account of virtue in his agent-based sentimentalist virtue ethics (Slote 1997, 2007). However, it is not clear whether Slote’s theory as a whole applies to Mencius’accounts of other virtues, such as justice, ritual propriety, and wisdom. It might be possible that, in theory, Mencius could have given an account of these virtues in terms of benevolence and empathy, as Slote has done. However, such an account seems to be missing in theMencius.

The Confucians are “deontologists”in the sense that they believe in the exis-tence of constraints on the promotion of the good. Both Mencius and Xunzi use almost the same words to emphasize the existence of such moral barriers to the promotion of the good:“if one needs to undertake an unjust action, or to kill an innocent person, in order to gain the whole world, one should not do it”(Mencius 2A2; Xunzi 11.1a). Mencius claims that the rulers who send people to die in aggressive wars or take away people’s livelihood through heavy taxation are no different from those who kill an innocent person with a knife (Mencius1A3, 1A4,

3B8), and that scholar-officials should not help the rulers make the state

prosper-ous by means other than the virtue politics of benevolence (Mencius4A14, 7A33).

YANG XIAO

The Confucians have at least two types of justification for their normative

claims about virtue and virtue politics: (a) arguments based on a theory of human nature, and (b) pattern-based, consequentialist arguments.

The first type can be found only in theMencius. It relies on what we may call

Mencius’ perfectionist and expressivist theory of human nature, which consists of two main ideas: (1) everyone’s “human nature” (xing) is rooted in his or her heart–mind, which is the innate dispositions of virtues such as benevolence, justice, ritual propriety, and wisdom, and this is what distinguishes humans from non-human beasts; (2) human nature is a powerful, active, and dynamic force; it necessarily expresses itself in the social-political world. In other words, the inner nature must manifest itself in the outer (the human body as well as the social world). This is why, for Mencius, virtue politics is not just a normative ideal; it is alsoreal, and it necessarily becomes reality in human history.

Mencius sometimes uses “xing” as a verb, which means to “let xing be the source of one’s action.” He claims that the sages (virtuous persons) always let xing be the motivational source of their virtuous actions; their virtuous actions

flow spontaneously from xing. In other words, when human nature expresses

itself as human action, it would necessarily be virtuous action.

This reconstruction of Mencius’ view as an argument based on an essentialist theory of human nature is certainly not the only way to interpret theMencius. In fact, some scholars have argued that Mencius does not have an essentialist theory of human nature (Ames 1991). There has been a more general debate about whether the Confucians have rational arguments based on metaphysical theories of human nature, and the debate often takes place in the context of a comparative study of Confucian and Aristotelian ethics (MacIntyre 1991, 2004a, b; Sim 2007; Yu 2007; Van Norden 2007). There has also been a debate about how to understand the concept of human nature (xing) in Chinese philo-sophy, whether it should be translated as “human nature” at all, and whether it is an innate disposition or a cultural achievement (Graham 2002; Ames 1991; Bloom 1997, 2002; Shun 1991, 1997; Liu 1996; Ivanhoe 2000; Lewis 2003; Munro 2005; Van Norden 2007).

The second type of justification, namely the pattern-based, consequentialist mode

of compassion and empathy, he will rule the world as easily as rolling it on his palm”(2A6).

It can be shown that the pattern-based, instrumentalist mode of justification is

one of the most popular among all the Chinese philosophers, even though they do not use the technical terms we have been using here, such as “the good,” “means,” “end,”and“instrumental rationality.”However, the lack of the general term does not imply the lack of the concept. Confucius, Mencius, and Xunzi were the first in China to use various concrete paradigm cases of instrumental

irrationality to talk about people who desire an end, yet refuse to adopt the correct means to the end (Mencius 1A7B, 2A4, 4A3, 4A7, 5B7; Xunzi7.5, 16.4). For instance, since Confucius did not have a general term for “rational” or “irrational,” when he spoke of a case in which someone desires an end and at the same time does not want to adopt the necessary means to that end, Con-fucius would say that this person is just like someone who “wants to leave a house without using the door”(Analects 6.17).

Mohist ethical theory

Let us now turn to Mohism (Schwartz 1985: 135–72; Graham 1989: 33–64; Van Norden 2007: 139–98). Mozi (480–390 BCE), the founder of Mohism, lived sometime after the death of Confucius and before the birth of Mencius. The founding text of Mohism, theMozi, is a very complex text with many layers. It was certainly not written by a single author; there are at least three sets of ideas, representing the views of three subgroups of Mohists (Graham 1989). Mohism as a school of thought was once the only rival to Confucianism, before the rise of Daoism and Legalism. But Mohism disappeared around the early years of the Han Dynasty (206 BCE to AD 220), until it was rediscovered by scholars in the Qing Dynasty (AD 1644–1911).

Like the Confucians, the Mohist notion of the ideal society is that it must have not only external goods –such as the state being orderly and prosperous (Mozi 126–8, see Yi-Pao Mei 1929) – but also moral character. However, their specifi

-cations of the moral character of their ideal society are not always the same. Both the Confucians and the Mohists believe in universal altruism, which is that thescopeof a virtuous person’s caring should be universal, which implies that he or she should care about not only those who are near and dear but also those who are strangers. However, they have different views about the intensity of

the caring: for the Confucians, one should care about the near and the dear more than strangers, but the Mohists insist that one must care about everyone in the world equally and impartially. They are the first ones in China to have

argued for the general obligations of “impartial caring”(jian-ai) (Wong 1989). In terms of how to evaluate the moral status of actions and policies, some of the Mohists are factoral consequentialists. Unlike the internalist Confucians,

YANG XIAO

who emphasize internal factors such as emotions and dispositions of the agent, some of the Mohists claim that a policy ought to be adopted if, judging from an impartial point of view, it promotes benefits for all people. Hence, unlike the

Confucians, these Mohists are “externalists” in the sense that they define right

actions in terms of consequences external to the agent.

Like the Confucians, some Mohists are “deontologists”in the sense that they believe in the existence of moral barriers to the promotion of the external goods. For instance, a ruler should not adopt“unjust”actions or policies such as taking the land that belongs to other states, or“cruel”actions or policies such as killing innocent people (Mozi158). They claim that all aggressive wars are unjust, and that only self-defensive wars can be justified, and they believe it is their obligation to help small

states to defend themselves against aggressors (Mozi98–116, 128, and 257–9). Some of the Mohists have a program for the realization of an ideal society, but their recommendation is not Confucian virtue politics. They do not consider virtue politics to be the best means to achieve their ideal society, and they are thefirst theorists in China to give a systematic account of how to design political

institutions to guarantee peace and civil order. Unlike the Confucians, they do not believe that virtue has transformative power; instead they believe that insti-tutions with a mechanism of reward and punishment need to be created to guarantee that there will be uniformity of opinions about justice and morality, that good deeds will be rewarded and bad ones punished, and that good and capable people will be promoted.

Some of the Mohists justify this program by appealing to their theory of human nature, which is radically different from the Mencian theory of the innate

goodness of human nature. The Mohist theory is somewhat akin to a Hobbesian view, which is that human beings naturally seek rewards and avoid punishments. In their justification of the institutional solution to the practical problem of how

to bring civil order to the world, the Mohists assume that people’s strongest motives are their desire for reward and aversion of punishment, and they believe that people will behave rationally and morally when certain institutions with mechanisms of reward and punishment are in place.

Mohism and Confucianism are similar in terms of their belief in the existence of moral constraints, as well as their conviction that an ideal society must have moral character. As we shall see, both are in sharp disagreement with the Legal-ists, who deny the existence of any constraints.

Legalist ethical theory

Legalism. For twenty-one years (359–338BCE), Shang Yang was the architect of what was later known as Shang Yang’s reform in the state of Qin, abolishing Confucian virtue politics (de-zheng) and replacing it with Legalist “ punishment-based politics”(xing-zheng). Shang Yang was mainly responsible for having made Qin into the most powerful state among the warring states; he laid down the foundation for its eventual unification of China in 221 BCE. Although Legalism was tremendously influential as a political practice, as a school of thought it was

not as widespread as Confucianism and Daoism; very few philosophers labeled themselves Legalists.

The Legalists were often powerful officials or advisers to rulers, and their

theory of the good is that a ruler ought to pursue only one end, namely the external goods of the state, such as order, prosperity, dominance, and strength (Book of Lord Shang 199, see Duyvendak 1963). By a state being orderly, they mean that crimes should be completely abolished (203), and they do not hesitate to punish light crimes with heavy punishments, especially the death penalty. To make their state dominant, they advocate aggressive warfare at the expense of the well-being of ordinary people. In achieving such ends, the Legalists do not care whether the state has moral character, such as whether it has a just legal system. The Legalists are “factoral consequentialists”in the sense that they determine whether an action or policy ought to be adopted by looking at whether it pro-motes the external goods of the state. Since what determines the Legalists’ evaluation of the moral status of actions is external to the agent, they are “externalists.”They deny that there are constraints on a ruler’s actions; the ruler can do anything necessary to promote their goals, including adopting policies that are unjust.

The Legalists rely on a theory of human nature to justify their punishment-based politics (xing-zheng). The basic idea is that human beings have only two basic desires or emotions: greed and fear, which is why they like rewards and dislike punishment (Book of Lord Shang 241). From this Shang Yang claims that the following pattern exists: if a ruler governs by punishment, people will be fearful, and will not commit crimes, out of fear (Book of Lord Shang229–30). In other words, the best means to achieve the legalist ideal society is to rely on physical force, as well as the threat of physical force.

This is in stark contrast with the Confucian belief that the best means to achieve the Confucian ideal society is through virtue, not force. Shang Yang turns the Confucian idea upside down:“Punishment produces force; force pro-duces strength; strength propro-duces awe; awe propro-duces virtue. [Therefore], virtue comes from punishment” (Book of Lord Shang 210). And he further concludes, “In general, a wise ruler relies on force, not virtue, in his governing”(243). In the Legalists’ justification, they are making two bold assumptions about human

nature:first, fear is the strongest moral emotion; second, people’s actions can be completely controlled by inducing fear. The Legalists also reject the Mencian idea that human beings’innate dispositions are the only source for morality.

YANG XIAO

The debate between Confuciande-zheng (virtue politics) and Legalistxing-zheng (punishment-based politics) is one of the most important and long-standing debates in the history of China, which arguably still has great relevance to the ethical and political life in China today.

Daoist ethical theory

The two main founders of Daoism (Graham 1989: 170–235; Schwartz 1985: 186– 254) are Laozi (Csikszentmih and Ivanhoe 1999) and Zhuangzi (Kjellberg and Ivanhoe 1996). Unlike in the case of the Confucians, the Mohists, and the Leg-alists, it is still disputed by scholars today whether Laozi is a real historical

figure. However, it is commonly acknowledged that Zhuangzi might have been a

real figure, although we are unsure of his dates (he might have lived before

Xunzi). Despite the lack of knowledge of Laozi and Zhuangzi as historicalfigures,

the two texts that are attributed to them, the Daodejing and the Zhuangzi, have been immensely influential throughout Chinese history. They are read not only

by the Daoists but also by the Confucians, and when Indian Buddhism was introduced to China, many Buddhist concepts were first translated into Daoist

terms. The later development of Chinese philosophy owes much to both Daoism and Buddhism, although Confucian ideas still remain the core of the philoso-phical canon.

The Daoists radically disagree with everybody else’s notion of the ideal society. Laozi rejects the Legalist regime in which, as Laozi puts it,“the ruler is feared.”However, Laozi claims that the Confucian regime, in which“the ruler is loved and praised,” is only the second best, and the best is the Daoist state where the ruler is “a shadowy presence to his subjects” (Daodejing Ch. 17, see Lau 1964). In other words, like the Confucians, the Daoists are opposed to the Legalists’ emphasis on punishment, but they are also opposed to the Con-fucians’ emphasis on virtues and social rules, and they ridicule the Confucians’ and Legalists’obsessive aspiration to unify China.

Laozi’s justification for the Daoist ideal society and its political program is

pattern-based. In fact, almost every chapter of the Daodejing contains pattern-statements. Laozi believes that patterns in nature are the best model for under-standing patterns in human affairs. Based on his observations of patterns both

in society and in nature, Laozi rejects the Confucian idea about the necessity of social rules and rituals; he thinks that the best way to bring about an ideal society is through the power of moral exemplars, or “teaching without words” (DaodejingChs 2, 43, 56).

(Daodejing Ch. 74). Laozi further says that only Heaven, which he calls “the Master Carpenter,”is in charge of matters of life and death, and the state should not kill on behalf of Heaven. And this is because of the following pattern: “In chopping wood on behalf of the Master Carpenter, one seldom escapes chop-ping offtheir own hands instead” (DaodejingCh. 74).

Zhuangzi is much more radical than Laozi both in terms of the style and con-tent of his thinking. In terms of style, it is difficult to find straightforward

for-mulations of theory and argument in the Zhuangzi. What one finds instead are

parables and seemingly strange stories: Zhuangzi himself as a character who dances and sings at the funeral of his wife; a large fish transformed into a bird

with wings covering half of the sky; a legendary bandit making fun of Confucius; abstract conceptions such as“Knowledge”becoming human characters, meeting up with the impersonation of “Do-Nothing-Say-Nothing,” and so on and so forth. And all of these are told in a distinctly Zhuangzian style that is indirect, ironic, and elusive; it is almost impossible to recover argument and theory from the text. Of course, this has not stopped scholars offering systematic exegesis

that assimilates it to philosophical ideas. For example, it has been suggested that Zhuangzi offers an epistemological argument against the Confucian normative

claims; his argument seems to be a “sceptical” one, which is that there simply exists no neutral or objective perspective from which one can know which nor-mative claims are valid (Kjellberg and Ivanhoe 1996). It has also been suggested that Zhuangzi is a relativist (Hansen 1992). There are certainly passages that can be easily interpreted to support all of these readings.

It can be argued that Zhuangzi also offers an ontological argument against the

Confucian expressivist theory of human nature. He denies that the Confucian virtues and social rules are the expressions of human nature or the essence of humanity. We may attribute to him an anti-expressivist theory of human nature, which is that human beings have no essence or nature, and the true self is empty and without any content, form, or structure, especially not the Confucian hier-archical structure with the heart–mind as the master organ. For Zhuangzi, this is why the Confucian rituals and virtues do notexpress, but rathercover anddistort, humanity (ZhuangziCh. 2).

If one does not want to attribute any epistemological or ontological theories to Zhuangzi, one may make sense of Zhuangzi by saying that he is trying to articu-late a new set of values, of which abstract freedom is the most important. Instead of saying that Zhuangzi holds an ontological view that humanity is empty and without content, we may say that Zhuangzi holds a value judgment, which is that anything concrete and substantive is a limitation on freedom. Zhuang seems to be the first to have discovered what might be called “negativity” or “abstract freedom,” to put it in Hegelian terms. If the Confucians could be said to have discovered that one can only become truly human and free when one partici-pates in a concrete and determinate ethical life that consists of social institutions such as family, community, and the state, Zhuangzi could be said to have

YANG XIAO

discovered abstract freedom, which is that one always has the capacity and free-dom to renounce any activity, to give up any goal, or to withdraw completely from this world. Zhuangzi sees any perspective or position that has determinate contents as a restriction on one’s freedom; similarly, he sees any particularization and objective determination of social life as a restriction or limitation on one’s free and purposeless wandering. He instinctively wants to spread his wings and

fly away from it.

It has become a cliché these days to say that Confucianism and Daoism com-plement each other (ru dao hu bu). But there is some truth to this popular saying, especially if we also add Buddhism to the mix. The essential tensions between Confucianism and Daoism, between Confucianism and Buddhism, have indeed been a major source of creativity in the history of Chinese philosophy.

Moral psychology and self-cultivation through spiritual exercise

The philosophical texts from early China can be divided into two groups: those that do, and those that do not, contain materials that deal with techniques con-cerning what to make of oneself, which may be called “self-cultivation,” “self management,” or “selfhood as creative transformation” (Nivison 1996, 1999; Ivanhoe 2000; Tu 1979, 1985). The Confucian and Daoist texts belong to thefirst

group, and the Mohist and Legalist texts to the second. The reason why the Mohists do not emphasize self-cultivation might have something to do with the fact that they think one’s belief can directly motivate actions (Nivison 1996), hence it is enough if one intellectually disapproves of bad desires. In the case of the Legalists, there is no space for self-cultivation in their thinking; they believe that the penal laws set up by the state are enough to produce the correct beha-viors (Xiao 2006b).