Commercial agriculture and the increased trade in agricultural commodities, including timber and pulp and paper, have led to the large-scale clearing of tropical forests1. Private companies have

become increasingly involved in efforts to tackle deforestation, with many committing to source sustainable forest products. Within these commitments, forest certification schemes are a key tool for companies to meet their sourcing goals.

Using data from the Forest 500, this briefing examines the prevalence of certification in company sustainability commitments and assesses the ability of certification-based commitments to protect remaining tropical forests. The briefing also explores options in addition to certification and provides recommendations on how company policies and certification schemes can be improved to ensure the long-term protection of tropical forests.

Key points

•

80% of Forest 500 companies with timber and/or pulp and paper sustainability policies

commit to use FSC and/or PEFC certified materials to meet their sourcing commitments.

•

The majority of these companies are headquartered in Europe and North America.

•

A large portion of forest products from tropical countries are consumed domestically, yet

policies by companies headquartered in these regions lag behind those headquartered in

Europe and North America.

•

Forest certification schemes lack strong traceability requirements.

•

Three quarters of certification-based company sustainability policies also lack strong

traceability requirements, meaning that many companies cannot guarantee the origin of

the products they source.

•

Although certification can help companies achieve sustainability goals, sourcing policies

should go beyond the requirements of certification schemes in order to further protect

tropical forests. This includes committing to zero net deforestation and implementing

stronger traceability systems particularly in high risk regions.

1 Schmitz, C., Kreidenweis, U., Lotze-Campen, H., Popp, A., Krause, M., Dietrich, J. P., & Müller, C. (2015). Agricultural trade and tropical deforestation: interactions and related policy options. Regional environmental change, 15(8), 1757-1772.

Achieving sustainable timber supply

chains: What is the role of certification

in sourcing from tropical forest

countries?

1. Global timber production and trade

In 2016, more than five billion cubic metres of timber and 800 million tonnes of pulp and paper were produced globally2. That amount of

timber alone is enough to fill Wembley Stadium in London, England more than 1,250 times. Almost half of global timber production came from seven countries: China, USA, India, Brazil, Russia, Canada, and Indonesia3.

Tropical forest countries produced less than a third of the global supply of timber, and pulp and paper4. And yet most global forest loss occurs

in these regions, with approximately seven million hectares of forest lost annually between 2000 and 20105. This forest loss is driven mainly

by agricultural expansion and illegal logging6.

In 2013, an estimated one-third of timber produced in nine tropical timber producing countries was harvested illegally7, driving

deforestation, and often opening up forest areas for agricultural expansion.

1.1 Forest certification

Forest certification schemes provide a quality assurance mechanism that products meet certain sustainability standards by conforming to sustainable forest management (SFM) practices8. There are

presently more than 50 forest management certification schemes9,

with the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) and the Programme for the Endorsement of Forest Certification (PEFC) the two largest and most internationally recognised. Both are multi-stakeholder initiatives which exclude production in priority forest landscapes10, and involve

civil society in decision-making.

2 FAO. (2017). FAOSTAT statistics database. Rome: FAO. Retrieved from http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/. 3 Ibid.

4 Ibid.

5 FAO. (2016). State of the World’s Forests 2016. Forests and agriculture: land-use challenges and opportunities. Rome: FAO. 6 Hoare, A. (2015). Tackling Illegal Logging and the Related Trade. What Progress and Where Next? London: Chatham House.

7 Hoare, A. (2015). Countries deined as Brazil, Cameroon, DRC, Ghana, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Papua New Guinea, and the Republic of the Congo. 8 Marx, A., & Cuypers, D. (2010). Forest certiication as a global environmental governance tool: What is the macro-effectiveness of the Forest Stewardship Council?. Regulation & Governance, 4(4), 408-434.

9 FAO. (2017). Sustainable Forest Management (SFM) Toolbox. Forest Certiication. Retrieved from http://www.fao.org/sustainable-forest-management/ toolbox/modules/forest-certiication/in-more-depth/en/

10 Deined as intact forest landscapes, high conservation value areas, primary and/or natural forest.

Comparing FSC and PEFC systems

• Although FSC was originally designed for the tropics and PEFC for temperate forests, both standards now cover both environments.

• FSC certified forests are found in 82 countries, and PEFC in 34 countries.

• Both standards offer Chain of Custody (CoC) certification, providing a quality assurance that certified timber is separated from non-certified sources.

• Both standards have similar goals and offer similar assurances of SFM. The main difference is their approach to certification.

• The FSC sets their own standard, using a ‘top down’ approach. Forest owners must meet FSC Principles and Criteria to achieve certification.

11 PEFC. (2017). Double Certiication FSC and PEFC – estimation end 2016. Retrieved 22/09/2017, from: https://pefc.org/resources/brochures/organizational-documents/2363-estimated-total-global-double-certiied-area-fsc-pefc-end-2016

12 Values calculated from FSC Facts & Figure January 2017 (https://ic.fsc.org/en/facts-and-igures) and PEFC Global Statistics December 2016 (https://pefc. org/images/documents/PEFC_Global_Certiicates_-_Dec_2016.pdf).

13 Ibid.

Country Production (M m3)a

Certified Area (M ha)b

Forest Change

(%/yr)c Key Export Regions d

Brazil 304.6 6.5 -0.2 EU, China, USA

Indonesia 135.8 4.7 -0.7 China, Japan, Republic of Korea

DRC 87.3 0.0 -0.2 EU, China

Cameroon 15 0.9 -1.1 China, EU, USA

Congo 4.1 2.6 -0.1 China, EU, USA

a. FAOSTAT, b. FSC/PEFC statistics, c. Global Forest Resource Assessment, d. resourcetrade

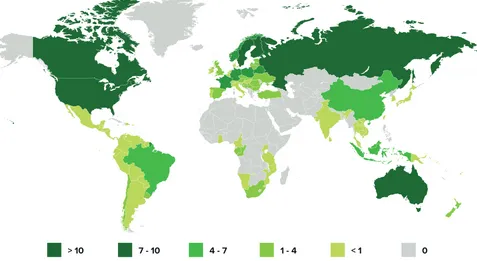

Figure 1: Combined area of FSC and PEFC certiied forests at the end of 2016 (million ha).

> 10 7 - 10 4 - 7 1 - 4 < 1 0

As of 2016, approximately 10% of global forests across 82 countries were certified under FSC or PEFC (Figure 1)11. Close to 84% of certified

forests are located in Europe and North America (not including Mexico)12, mostly consisting of temperate and boreal forests.

Less than 7% of certiied forests are located in tropical forest countries.

More than half of countries with tropical forests have no FSC or PEFC

certiied forest area13, while certiication uptake is low in those countries

that do (Table 1). The majority of certiied timber from countries with

tropical forest is exported to markets in Europe and the USA.

2. Use of certification-based commitments

in sustainable sourcing policies

Global Canopy’s Forest 500 identifies and ranks the most influential powerbrokers in the race towards a deforestation-free global economy. These powerbrokers include the most influential producers, processors, manufacturers, and retailers within forest risk commodity supply chains. The 2016 Forest 500 assessment included 210 companies14

using tropical timber in their operations, including those that used high volumes of paper-based packaging. The robustness of company commodity policies to address deforestation across their supply chains are assessed in the Forest 500 using a number of indicators15.

Companies score points for sourcing FSC and PEFC certified materials, but the certification schemes alone do not meet Forest 500 traceability requirements. This is because FSC and PEFC CoC systems only require that certified materials are identified and separated from non-certified materials. To be awarded points for traceability, companies must commit to full traceability to the mill level at a minimum. This level of traceability is important as it helps prevent products from being fraudulently labelled as certified, which is especially relevant in high risk tropical countries with high rates of corruption and illegal logging.

2.1 Use of certification schemes in

Forest 500 sustainability policies

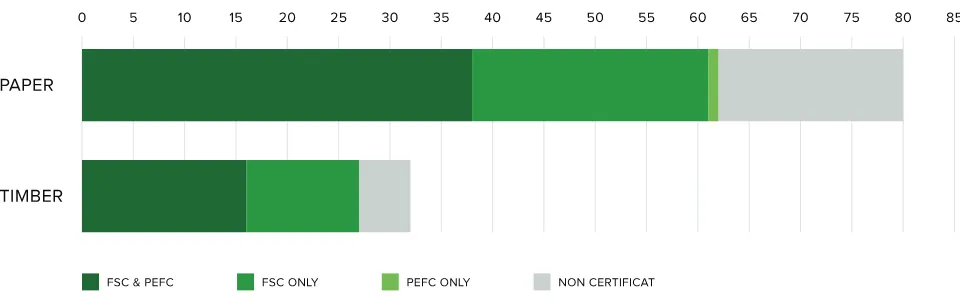

Forest 500 data shows that companies are increasingly using

certification schemes to meet their sourcing requirements. Of the 47 companies assessed for timber, 32 had a specific policy for timber, and 27 of these included the use of certified materials to meet sourcing requirements (Figure 2). The number of sustainability commitments is lower in the 208 companies assessed for paper, with only 80 having a specific paper policy. Of these, 62 included the use of certified

materials (Figure 2). Overall, the number of certification-based policies increased by more than 15% between 2014 and 2016.

14 This includes 45 companies assessed for both timber and pulp and paper, 163 companies assessed only for paper (mainly for paper-based packaging), and 2 companies assessed only for timber.

15 Global Canopy Programme. (2016). The Forest 500: 2016 Company Assessment Methodology. GCP, Oxford, UK.

Of the 89 companies using certification-based policies (Figure 2), only 22% include enhanced traceability systems to at least the mill level. The lack of traceability systems and reliance on certification CoC systems means that the majority of companies that source certified forest products cannot guarantee the origin of the wood they are sourcing.

2.2 Regional variation in

certification-based policies

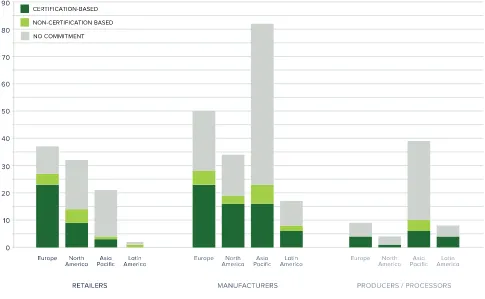

Most deforestation occurs in tropical forest countries16, yet certification

uptake in these regions is limited (Figure 1). The majority of timber produced in tropical countries remains in domestic markets, including in Indonesia where more than three quarters of production is consumed domestically17.

Domestic demand for certified products in these countries is low as the cost of obtaining certification is high and companies have to compete with cheaper conventional and illegally harvested timber18.

Smallholders in particular are often excluded by the high costs of obtaining certification19. Given this low demand, it is unsurprising

that few Forest 500 retailers in Asia-Pacific or Latin America have certification-based commitments (Figure 3), with the majority of certification-based commitments in these regions coming from manufacturers and producers/processors, many of which export their products to Europe and North America.

16 FAO. (2016). State of the World’s Forests 2016. Forests and agriculture: land-use challenges and opportunities. Rome: FAO.

17 Kishor, N., & Lescuyer, G. (2012). Controlling illegal logging in domestic and international markets by harnessing multi-level governance opportunities. International Journal of the Commons, 6(2).

18 Tacconi, L. (2012). Illegal logging: law enforcement, livelihoods and the timber trade. Earthscan.

19 Auer, M.R. (2012). Group forest certiication for smallholders in Vietnam: an early test and future prospects. Human ecology, 40(1), 5-14.

Certified timber from tropical countries is mainly exported to markets in Europe and North America20. In 2016, more than two thirds of Forest

500 companies using certification-based commitments for timber and paper were headquartered in these regions (Figure 3). This may reflect higher demand for certified materials, as well as tighter restrictions on illegal timber imports (i.e. EU Timber Regulation and Lacey Act).

2.3 Deforestation commitments

In 2016, 31 Forest 500 companies assessed for timber and/or pulp and paper had zero/zero net deforestation commitments, with 90% of commitments covering the entire company operations. This number has more than doubled since 2014. Three quarters of companies with these overarching deforestation commitments in 2016 also had certification-based commitments.

Marks & Spencer (M&S) is an example of a retailer that has committed to eliminate commodity-driven deforestation from its supply chains by 202021. To achieve this goal, they have gone beyond the requirements of

certification in their sourcing policies, allowing both credibly certified timber and non-certified timber to meet their sourcing criteria.

This flexibility enables M&S to source sustainably from regions, such as the tropics, where there is low coverage of certification.

Non-certified materials must include additional information to demonstrate that materials were sourced sustainably, including documentation of material trade between actors and information on the procurement policies of all actors in the supply chain. Their policy also excludes timber sourced illegally or from high conservation value areas and plantations converted from natural woodland.

Although this is a strong policy, it could be strengthened further by requiring traceability to forest source rather than forest origin country.

Zero vs. Zero Net Deforestation

• Zero net deforestation allows for forest conversion as long as it is compensated with the planting of an equal area of forest22;

• Zero deforestation goes a step further and prohibits the clearing or conversion of any forests23.

• A key challenge in forest product sectors is that sourcing forest products inevitably involves the removal of trees and thus zero deforestation is not feasible. Companies often use these terms interchangeably in policies and the definition of a “forest” is not always clear, with forest thresholds most often determined by forest cover (i.e. proportion of an area covered by forests)24.

• As planting new forests to compensate for harvesting in primary forests does not restore the same level of ecosystem services in the harvested forest, companies sourcing forest products should develop strong zero net deforestation policies that exclude the conversion of intact, high conservation value, primary and natural forests.

20 Hoare, A. (2015). Tackling Illegal Logging and the Related Trade. What Progress and Where Next? London: Chatham House.

21 Marks & Spencer. (2016). Protecting Forests. Retrieved 23/10/2017, from: https://corporate.marksandspencer.com/plan-a/our-approach/business-wide/ natural-resources/protecting-forests

22 Brown, S., & Zarin, D. (2013). What does zero deforestation mean?. Science, 342(6160), 805-807. 23 Ibid.

3. Recommendations

Certification schemes are one tool that companies can use to reduce deforestation. In the following section, we provide recommendations on how certification schemes and company policies can be improved to better protect tropical forests.

Company policies going beyond certification

Certification schemes can be complemented with zero net

deforestation commitments that commit to not impacting priority forest landscapes, to sourcing timber from responsibly-managed plantations, and which prioritise recycled materials.

Robust traceability systems, particularly in high risk tropical countries with high levels of corruption and illegal timber, are essential to allow materials to be tracked to their forest source. This enables companies to guarantee sustainable sources and mitigate impacts, increasing consumer trust in sustainability claims. Some companies, such as Home Depot, have introduced internal systems to provide this traceability25. Increased public disclosure across supply chains

also enhances commitments, allowing sustainability claims to be independently verified.

Adopting sourcing policies based on sustainability principles rather than solely on the exclusion of non-certified materials, provides companies with more flexible sourcing options and can support increased inclusion of smallholder suppliers. Given the low coverage of certification26 and high rate of illegal logging27 in many tropical

countries, it is especially important that companies in these regions adopt more flexible sourcing policies. Smallholders in tropical regions are often excluded from participating in SFM initiatives, including certification schemes, as a result of limited financial and technical capacity28. By allowing both certified and non-certified materials

in company sourcing policies, companies will have additional

sourcing options, including increased access to timber products from smallholder producers. Increasing capacity and providing more secure livelihoods for smallholders can help to promote more responsible forest management practices in high risk regions.

Improving forest certification schemes

Strengthening monitoring and enforcement systems within certification systems (including CoC systems) can help to prevent fraud and mislabelling of products as originating from certified sources. Discrepancies in enforcement of certification standards29

undermines sustainable timber production, leading to consumer

mistrust. Monitoring product flows across supply chains and increasing the frequency of planned and unannounced audits can better help substantiate company sustainability claims.

More detailed data collection in certified timber concessions will allow better monitoring of the impacts of certification schemes. Few studies are currently able to examine the causal link between certification and social and environmental benefits, with results unable to distinguish whether benefits are due to certification or local context30.

25 Home Depot. (2017). Wood Purchasing Policy. Retrieved 23/10/2017, from: https://corporate.homedepot.com/sites/default/iles/image_gallery/PDFs/Wood_ Purchasing_Policy_2017.pdf

26 Auer, M.R. (2012). 27 Hoare, A. (2015).

28 Marx, A., & Cuypers, D. (2010).

29 Smit, H., McNally, R., & Gijsenbergh, A. (2015) Implementing Deforestation-Free Supply Chains – Certiication and Beyond. SNV.

4. The path towards a zero-deforestation

economy

Reliance on certification-based commitments is insufficient to shift towards a deforestation free economy, particularly given the low coverage of certification in tropical countries. There is a clear need for market incentives to increase demand for sustainable forest products in tropical forest countries alongside action by companies active in these domestic markets which currently lag in sustainability policies. Through collective action between all actors in timber, pulp and paper supply chains, we will be able to better protect tropical forests.

Citation:

Please cite this brieing as: Guindon, M. 2017. Achieving sustainable timber supply chains: What is the role of certiication in sourcing from tropical forest countries? Global Canopy.

Lead author:

Michael GuindonContributing authors and reviewers:

Helen Bellield, Helen BurleyAcknowledgments

The authors would also like to express their thanks to Sarah Rogerson, Gleice Lima, Sarah Lake and Stuart Singleton-White for their insights and comments on the report.

Funding

This publication was inancially supported by UK aid from the UK government; however the views expressed in this report do not necessarily relect the UK government’s oficial policies.

About the Forest 500:

The Forest 500, an initiative of the Global Canopy, is the world’s irst rainforest rating agency. It identiies and ranks the most inluential companies, inancial institutions, countries and subnational jurisdictions in the race towards a deforestation-free global economy. To ind out more about our work visit www.forest500.org

Contact

To contact the Forest 500 team, please write to [email protected].

About Global Canopy:

Global Canopy is a tropical forest think tank working to demonstrate the scientiic, political and business case for safeguarding forests as natural capital that underpins water, food, energy, health and climate security for all. Our vision is a world where rainforest destruction has ended. Our mission is to accelerate the transition to a deforestation free economy. To ind out more about our work visit www. globalcanopy.org

The contents of this report may be used by anyone providing acknowledgement is given to Global Canopy. No

representation or warranty (express or implied) is given by Global Canopy or any of its contributors as to the accuracy or completeness of the information and opinions contained in this report.

Global Canopy sits under The Global Canopy Foundation, a United Kingdom charitable company limited by guarantee, charity number 1089110.