NEW KING JAMES VERSION HOLY BIBLE

AN UNDERGRADUATE THESIS Prestented as Partial Fulfilment of the Requirement

For the Degree of Sarjana Sastra in English Letters

By

LUCIA KURNIADI Student Number: 044214151

ENGLISH LETTERS STUDY PROGRAMME

DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LETTERS

FACULTY OF LETTERS

SANATA DHARMA UNIVERSITY

YOGYAKARTA

i

THE SPELLING OF EARLY MODERN ENGLISH

AS SEEN IN

THE KING JAMES VERSION 1611 HOLY BIBLE

COMPARED TO

NEW KING JAMES VERSION HOLY BIBLE

AN UNDERGRADUATE THESIS

Prestented as Partial Fulfilment of the Requirement For the Degree of Sarjana Sastra

in English Letters

By

LUCIA KURNIADI

Student Number: 044214151

ENGLISH LETTERS STUDY PROGRAMME

DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LETTERS

FACULTY OF LETTERS

SANATA DHARMA UNIVERSITY

YOGYAKARTA

iv

“Those who don’t give up will win in the end”

Surely goodnes and mercie shall followe me

all the daies of my life:

and I will dwell in the house of the Lord for euer

(KJV 1611, Psalm 23: 6)

YÉÜ

Ytà{xÜ? ]xáâá V{Ü|áà tÇw [ÉÄÄç fÑ|Ü|à

`Éà{xÜ `tÜç

`ç Wtwwç UxÇÇç ^âÜÇ|tw| 9 Åç `ÉÅ fÜ| fâátÇà|

`ç UxÄÉäxw f|áàxÜ TÄÉçá|t ^âÜÇ|tw|

`ç UxÄÉäxw UÜÉà{xÜ fxutáà|tÇ U|ÄÄç ^âÜÇ|tw|

v

LEMBAR PERNYATAAN PERSETUJUAN

PUBLIKASI KARYA ILMIAH UNTUK KEPENTINGAN AKADEMIS

Yang bertanda tangan dii bawah ini, saya mahasiswa Universitas Sanata Dharma:

Nama : Lucia Kurniadi

Nomor Mahasiswa : 044214151

Demi pengembangan ilmu pengetahuan, saya memberikan kepada Perpustakaan Universitas Sanata Dharma karya ilmiah saya yang berjudul:

The Spelling of Early Modern English as Seen in the King James Version 1611 Holy Bible Compared to New King James Version Holy Bible

beserta perangkat yang diperlukan (bila ada). Dengan demikian saya memberikan kepada Perpustakaan Universitas Sanata Dharma hak untuk menyimpan, mengalihkan dalam bentuk media lain, mengelolanya dalam bentuk pangkalan data, mendistribusikan secara terbatas, dan mempublikasikannya di Internet atau media lain untuk kepentingan akademis tanpa perlu meminta izin dari saya maupun memberikan royalty kepada saya selama tetap mencantumkan nama saya sebagai penulis.

Demikian pernyataan ini yang saya buat dengan sebenarnya.

Dibuat di Yogyakarta

Pada tanggal : 24 Maret 2009

Yang menyatakan

vi

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Thanks to Jesus Christ for His kindness, so that I finally completed the thesis

writing.

There are a lot of people who have guided, supported and helped me in

completing this thesis writing. Therefore, I would like to thank:

1. Dr. Fr. B. Alip, M.Pd., M.A as the advisor for guiding and giving a lot of

advises so that I finally complete this research.

2. J. Harris Hermansyah S., S.S., M.Hum as the reader for giving suggestions

and advises.

3. All lecturers of English Letters study Programme of Sanata Dharma

University, and Mbak Ninik.

4. My parents Benny Kurniadi and Sri Susanti, my beloved sister Aloysia

Kurniadi, my beloved brother Sebastian Billy Kurniadi, uncles and aunties,

and all of my cousins.

5. My friends Kiki, Dinda, Vonny, Theo, Hartati, Steven, Frans, Shendy.

6. My best friends Karisma Kurniawan, Yohanes Krisostomos, Ardi Nugroho,

Reena Rai, Wahyu Puspita Sari, Scholastika Ardianita, Hilda Dina Santoja,

Nur Indah, Vina Christiana, Prawira Atmaja.

I realize that this thesis has not been perfect yet. Therefore, the criticisms and

suggestions from whoever read this thesis are welcome. May God bless all of those

who have helped me throughout my study.

vii

LEMBAR PERNYATAAN PERSETUJUAN... v

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS... vi

TABLE OF CONTENTS ... vii

ABSTRACT ... ix

ABSTRAK ... x

CHAPTER I: INTRODUCTION ... 1

A. Background of the Study ... 1

B. Problem Formulation ... 2

C. Objectives of the Study ... 3

D. Benefit of the Study ... 3

E. Definition of Terms ... 3

CHAPTER II: THEORETICAL REVIEW ... 5

A. Review of Related Theories ... 5

1. English Modern English Problem ... 5

2. Spelling of Early Modern English ... 7

3. The English Alphabets ... 10

4. Classical Latin Spelling ... 11

5. History of the Holy Bible in English ... 12

6. The Sound System of English ... 14

B. Theoretical Framework ... 17

CHAPTER III: METHODOLOGY ... 18

viii

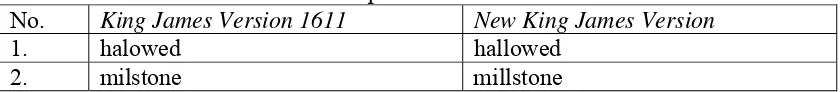

E. The Doubled Letter ... 43

F. Grammar Shift ... 46

G. The Compound Differences ... 47

H. Negative Morpheme Shift ... 49

I. The Singled Letter... 49

J. Word Adaptation... 52

K. Letter Shift ... 52

L. Misspelling... 76

CHAPTER V: CONCLUSION ... 77

BIBLIOGRAPHY ... 79

APPENDICCES... 80

ix

ABSTRACT

LUCIA KURNIADI. The Spelling of Early Modern English as Seen in the King

James Version 1611 Holy Bible Compared to New King James Version Holy

Bible. Yogyakarta: Department of English Letters, Faculty of Letters, Sanata Dharma

University, 2009.

Before the Renaissance, England used French as its national language and English became the language of low-class people. However, after the Renaissance era, English became popular because the nobles tried using it to communicate with their people. Different from the Old English and Middle English, the early version of Modern English looks much simpler for us. The inflection system is reduced, as well as the gender. However, there is no particular rule about how to spell the words. Every author had his own spelling. Therefore, we can know who the author of a book is just from the spelling.

The purposes of this study are first to identify the spelling of the King James Version 1611 Holy Bible and second to understand the extent of its difference from Modern English. Therefore, there are one problem that is discussed namely how the spelling of Early Modern English is different from Modern English.

In this study I conducted a desk research which means that this study is done based on the theories from many sources and also the data from the King James Version 1611 Holy Bible especially the Gospel of Luke. Then, I compared it with the

New King James Version Holy Bible to know the differences

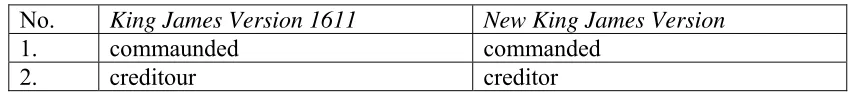

Based on the research result, there are many differences between the King James Version 1611 and the New King James Version. The differences are the letter addition 2.4%, the apostrophe ‘s addition 1%, the change of consonant orders 0.02%, letter deletion 40.8%, doubled letters 2.7%, grammar shifts 0.06%, compound differences 1.7%, negative morpheme shifts 0.04%, singled letters 8.6%, word adaptation 0.06%, the letter shifts 42.48%, and misspellings 0.1%.

x

ABSTRAK

LUCIA KURNIADI. The Spelling of Early Modern English as Seen in the

King James Version 1611 Holy Bible Compared to New King James Version Holy

Bible. Yogyakarta: Jurusan Sastra Inggris, Fakultas Sastra, Universitas Sanata

Dharma, 2009.

Sebelum Renaisans, Inggris menggunakan bahasa Prancis sebagai bahasa nasionalnya dan bahasa Inggris menjadi bahasa untuk rakyat jelata. Akan tetapi setelah zaman Renaisans bahasa Inggris menjadi kembali terkenal karena para bangsawan menggunakannya untuk berkomunikasi dengan rakyat mereka. Berbeda dengan Inggris Kuno dan Inggris Pertengahan, versi awal Inggris Modern tampak sangatlah sederhana bagi kita. Sistem infleksi dan gender dikurangi. Bagaimanapun juga, tidak ada rumus umum untuk cara penulisan suatu kata. Setiap penulis mempunyai cara penulisannya sendiri. Oleh karena itu, kita dapat mengetahui penulis suatu buku dari cara penulisannya

Tujuan penelitian ini yang pertama adalah untuk mengidentifikasi cara penulisan King James Version 1611 Holy Bible dan yang kedua adalah untuk mengetahui sampai sejauh mana perbedaannya dengan Inggris Modern. Oleh karena itu, ada satu masalah yang didiskusikan yaitu bagaimana cara penulisan Inggris Modern Awal berbeda dengan Inggris Modern.

Dalam studi ini saya menggunakan metode penelitian kepustakaan yang berarti bahwa penelitian ini dilakukan berdasarkan teori-teori dari berbagai sumber dan data diperoleh dari King James Version 1611 Holy Bible terutama Injil Lukas. Kemudian saya membandingkannya dengan New King James Version Holy Bible

untuk mengetahui perbedaannya.

1

CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION

A. Background of the Study

Cable and Baugh (1978: 113-116) said that before the renaissance, England

used French as its national language and English became the language of low-class

people. However, after the renaissance era, English became popular again because the

nobles tried using it to communicate with their people. Different from the Old

English and Middle English, the early version of Modern English is much simpler.

The inflection system is reduced, as well as the gender. However, there is no

particular rule about how to spell the words. Every author had his own spelling.

Therefore, we can know who the author of a book is just from the spelling.

Basically, English used to be written as it sounded. However, people spoke

different varieties of English. A good example of an early Modern English text is

King James Holy Bible. It was translated from Latin by 54 experts in 1607 and

published in 1611. However, now, King James Holy Bible has been revised into

Modern English standard spelling but it still uses some archaic words such as thy, and

thou. Actually, early Modern English words are quite the same as today Modern

English. However, as I said before, because there was no standardization of spelling,

authors had their own spelling.

The reason why I have chosen this topic as my topic is that if I would like to

find texts of early Modern English is much easier than to find the Old English and

the Middle English ones. Different from Old English which is more like German,

early Modern English, of course, is more like today Modern English but it is still

different. The third reason is that King James Holy Bible is a very good sample text

of early Modern English and a very famous book that has many versions. Therefore,

if I wish to know about the history of English language, I should choose the Holy

Bible.

The next point is that I agree that there is no standardization of

spelling in the early Modern English. However, it does not mean that every author

has exactly different spelling.

I limit my study just in the spelling of the Early Modern English. In addition, I

also only take King James Bible which was translated at 1611 as my focus of the

study. Moreover, I chose the Gospel of Luke in random.

B. Problem Formulation

To guide the progress of this study, one research problems have been

formulated as follows:

C. Objectives of the Study

There are two objectives of this study. The first one is to identify the spelling

of the original version of King James Version Holy Bible. The second one is to

understand the extent of its difference from Modern English.

D. Benefit of the Study

There are two benefits of this study. The first benefit of this study is that the

reader knows more about the Early Modern English spelling. The second one is that

the reader can learn more about the history of English language.

E. Definition of Term

These following are the definitions of the technical terms that are used in this

study.

1. According to Cable and Baugh (1978: 199), Early Modern English is the English

language used around 1500-1600. It was also known as the Renaissance. It was

used in the end of Middle English to the beginning of Modern English.

2. According to Cable and Baugh (1978: 2-3), Modern English is the variety of

English language that we use today. It is used from the end of 15th century to now.

It is a living language that constantly changing.

3. According to Fromkin and Rodman (2003: 562-563), a spelling system is the

representation of the spoken language. The spelling of most English words today

4. In Menyingkap Alkitab (2005: 8), the King James Bible is an English holy bible

published to replace the Geneva Bible. It was also known as the Authorized

Version. The New Testament was translated from the Textus Receptus (Received

Text) edition of the Greek texts while the Old Testament was translated from the

Masoretic Hebrew text and the Apocrypha was translated from the Greek

Septuagint. It was translated by 54 experts in 1607 and published in 1611. It was

named as the King James Bible because King James I was the main supporter of

this holy bible. In 1982, it was revised and known as the New King James

5

CHAPTER II

THEORETICAL REVIEW

A. Review of Related Theories

1. Early Modern English problem

Baugh and Cable (1978: 201-216) said that different from Middle English

period that had revolutionary changes in grammar but not so great changes in

vocabulary, the early Modern English was a period when English just had slight

changes in grammar but the changes in vocabulary was very extensive. In that

time, the same as the other language in the European countries, English also faced

three problems. The first one is recognition in the field where Latin had been

supreme for centuries. The second one is the establishment of a more uniform

spelling. The last one is the enrichment of the vocabulary so it can fulfill the

demands for wider use.

First, recognition was a very hard problem at that time. Although English had

become the language of popular literature, Latin was still used in all fields of

knowledge. However, finally the demands were met after some scholar said that

they would rather use English than Latin. Translations literally poured from the

press in the course of sixteenth century. Many ancient works in Latin and Greek

Second, spelling in the sixteenth century was a real important discussion. The

problem is there is no accepted spelling for everyone. In short, it was neither

phonetic nor fixed. Although some people saw it as a chaotic, actually the

spelling of English was not as bad as that. There were limit to its variety and

inconsistency. Every author had his own consistent spelling. Some authors tried

to publish their books of spelling but it was not popular. However, finally Richard

Mulcaster and Dr. Johnson could make books of spelling which could be accepted

in common society.

The last, since the scholar monopoly Latin language throughout the Middle

Ages, the vernacular was untouched. In the Early Modern English time, when the

monopoly was broken, the deficiencies of English was seen at the same time.

English had not enough vocabulary to replace the classical language in expressing

thought from many fields. Therefore, translators of foreign books such as Latin,

French, and Italian books, borrowed some words and adapted them into English.

Crystal (2003: 56-57) said in his book the Cambridge Encyclopedia of The

English Language that there is no consensus about when the Early Modern

English period begins. Some people choose for the early date, 1400-1450, just

after Chaucer and the beginning of pronunciation shift. The others choose for a

late date, around 1500, after the printing revolution. In this period, the spelling

was unstable. It is not until nearly a century later that there is a uniformity in the

2. Spelling of Early Modern English

Fromkin and Rodman (2003: 562-563) said that writing does not represent the

spoken language perfectly, though it supposes to do that. Therefore, spelling

reform, in fact, is necessary. The irregularities between letters and phonemes is

one of unsolved problem until today. Different spelling for the same sounds,

silent letters, and missing letters also are the reasons that English needs a new

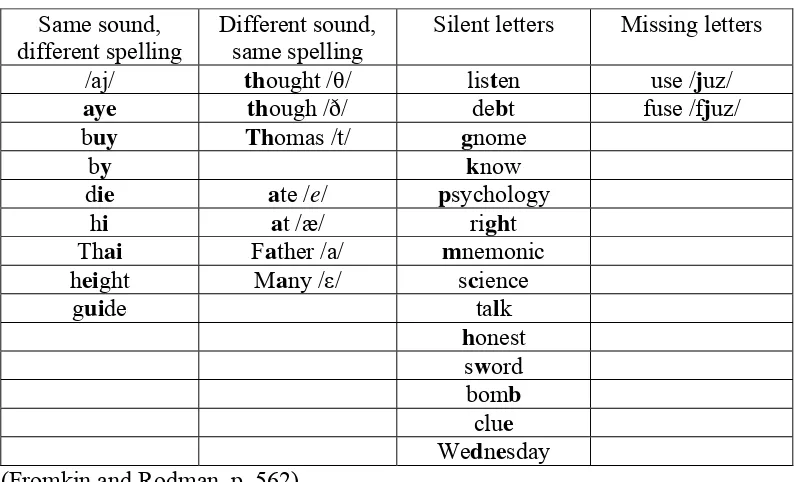

orthographic system, as seen in the table below:

Table 1: The irregularities of the English orthographic system

Same sound,

The spelling of most English words today is based on the spoken English in

the fourteenth, fifteenth, and sixteenth centuries because when the printing press was

introduced in the fifteenth century, the scholars realized that there was a need for

those times saw that to spell the same word consistently was unnecessary. For

example in Shakespeare’s plays, he spelled the first person singular pronoun as I, ay,

and aye. However, the scholars changed the spelling of English words based on their

etymologies. Therefore, where Latin had a b, they added a b even if it was

pronounced such as debt.

Crystal (2003: 66-68) also mentioned that even a generation after Caxton, the

English system remained in a highly inconsistent state although there were clear signs

of standardization. This can be seen even within the work of an individual printer or

author. Caxton, for example, in a single passage has both booke and boke (book), and

axyd and axed (asked). The printers were blamed because many of them were

foreigners and they were uncertain of orthographic traditions in English.

Later, Mulcaster published his Elementarie at the end of 16th century. It

provided a table listing of recommended spelling for nearly 9000 words. Vowels

especially came to be spelled in a more predictable way. There was increased use of

double-vowel (as in soon) or a silent –e (as in name) to mark length; and a doubled

consonant within a word became a more predictable sign of a preceding short vowel

(sitting) – though there continued to be some uncertainty over what should happen at

the end of the word (bed, and glad, but well, and glasse). In the 1630s, the use of u

and v was standardized. V was representing a consonant while u was representing a

vowel. These symbols were at first interchangeable, and then positionally

distinguished (with v used initially and u medially in a word). A similar

In 16th century, people began to use a capital letter at the beginning of every

sentence, proper name, and important common noun. By the early 17th century, the

practice had extended to titles (Sir), forms of address (Mistris) and personified nouns

(Nature). Emphasized words and phrases would also attract a capital.

According to Dent (2003: xxxiii-xxxv) In Early Modern English era, the most

common punctuation were the virgule (/), the period (.), and the colon (:). In Caxton,

the virgule had the function of modern comma, period, or semi colon; it fell out of

use in the 16th century, and was largely replace by the comma.

In the Early Modern English, there was no orthographic distinction between

simple plural and either singular possessive or plural possessive. Therefore, the words

sisters, sisters’, sister’s were spelled the same, sisters.

In the Early Modern English, sometimes two different words were spelled the

same such as tide which can mean either tide or tied. However, some words also

interchangeable such as travail which is now spelled as travel and travel that is

spelled travail now.

3. The English Alphabet

The following is the description of the development of the English

alphabet according to Crystal (2003: 258-264). The letter-shapes of the modern

alphabet in most cases are part of an alphabetic tradition which is over 3000 years

old. Old English was first written in the runic alphabet, but the arrival of Christian

letters, those are the character a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, i, k, l, m, n, o, p, q, r, s, t, u, x, y,

and z. They were applied to the Old English sound system in a systematic way.

After the Norman Conquest, there was a new letter, w. To this alphabet of 24

letters were added, from the Modern English era, v and j, respectively

distinguished from u and i, with which they had previously interchangeable. The

result is the 26-letter alphabet known today.

The letter i was a consonant in the Semitic alphabet, represented a vowel

in Greek, and came into Latin with both vowel and consonant values.

The history of the letter j in English dates only from the medieval period.

Originally a graphic variant of i, it gradually came to replace i whenever that

letter represented a consonant, as in major and jewel.

The ancestor of the letter u is to be found in the Semitic alphabet,

eventually emerging in Latin as a v used for both consonant and vowel. In Middle

English, both v and u appear variously as consonant and vowel, in some scribal

practice v being found initially and u medially. This eventually led to v being

reserved for a consonant and u for the vowel, though it was not until the late 17th

century that this distinction became standard.

The letter y is a Greek adaptation of a Semitic symbol, representing a high

front rounded vowel. In Roman times, it was borrowed to help transcribe Greek

4. Classical Latin Spelling

According to Fromkin and Rodman (2003: 563), the spelling reformers

saw the need for consistent spelling that correctly reflected the pronunciation of

words. However, many scholars, authors, and translators become overzealous.

Because of their reverence for Classical Greek and Latin, they changed the

spelling of English words to conform their etymologies. Therefore, in Early

Modern English many words borrowed from Latin were spelled according to their

Latin spelling. For example is the silent b in the word debt. The word debt comes

from the Latin word debita. Therefore, Early Modern English people spelled it as

debt although the b is silent.

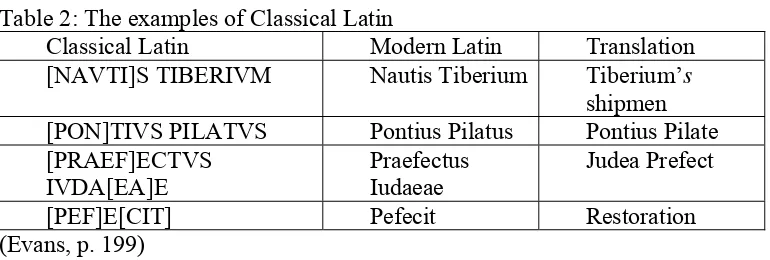

However, classical Latin is different from today Latin. In some old text

that is found in Israel, the Romans considered v and u as one letter as Evans wrote

in his book Fabricating Jesus. For note, the letters inside the square brackets are

the letters that is restored by the archeologist.

Table 2: The examples of Classical Latin

Classical Latin Modern Latin Translation [NAVTI]S TIBERIVM Nautis Tiberium Tiberium’s

shipmen [PON]TIVS PILATVS Pontius Pilatus Pontius Pilate [PRAEF]ECTVS

IVDA[EA]E

Praefectus Iudaeae

Judea Prefect

5. History of the Holy Bible in English

In Menyingkap Alkitab (2005: 6-8), it is said that because of the Pope’s will,

Jerome, a scientist, translated the Old Testament (in Hebrew) into Latin in

383-405 A.D. The translation was called Vulgate (means common or usual). Vulgate

became the standard text for more than 1000 years in the Roman Catholic Church.

When it came to England, Vulgate was translated into Old English, that was

called as Bede’s Bible, although it was not the standard text in the Church since

the Church forbade people to translate the Holy Bible into local languages to

avoid misinterpretation.

Then, in 1384 Wycliffe’s Bible was published followed by Tyndale’s New

Testament in 1525. The first English standard bible is the Great Bible. Like its

name, the Bible was in the very big size. Therefore, the Geneva Bible was

published in 1560 for the common people in Britain. In 1568, eight bishops

revised the Great Bible. This revision was called as the Bishop’s Bible. Although

it is not very popular, this Bible was accepted by the people as the substitute of

the Great Bible because of the authority of the Church and the government.

The next version is The King James Bible or Authorized Version. This bible

was used to replace the Geneva Bible. The translation was started in 1607 by 54

experts that were divided into six ‘companies’, each working on a separate section

of the Bible. The preliminary version took four years, and the final revision a

further nine months, and finally in 1611, this Bible was published as Authorized

because King James I become the main supporter. This Bible immediately

became the Great Britain Holy Bible.

It has been estimated that about 80% of the text of the Authorized Version

shows the influence of Tyndale’s New Testament which was published in 1525,

revised in 1534, and known as the first English vernacular text to be printed. For

example the two passages of Matthew 5:1-10 below is almost identical. However,

there was a development of spelling there.

Table 3: The Comparison between Tyndale’s New Testament and Authorized Version in spelling.

Tyndale Authorized Version

1 When he sawe the people, he went vp into a mountayne, and when he was set, his disciples came to hym,

1 And seeing the multitudes, he went vp into a mountaine: and when he was set, his disciples came vnto him 2 and he opened hys mouthe, and

taught them sayinge:

2 And he opened his mouth, and taught them, saying,

3 Blessed are the povre in sprete: for theirs is the kyngdome of heven.

3 Blessed are the poore in spirit: for theirs is the kingdome of heauen. 4 Blessed are they that morne: for

they shalbe conforted

4 Blessed are they that mourne: for they shall be comforted.

5 Blessed are the meke: for they shall inheret the erth.

5 Blessed are the meeke: for they shall inherit the earth.

6 Blessed are they which honger and thurst for rightewesnes: for they shalbe filled.

6 Blessed are they which doe hunger and thirst after righteousnesse: for they shall be filled.

7 Blessed are the mercifull: for they shall obteyne mercy.

7 Blessed are the mercifull: for they shall obtaine mercie.

8 Blessed are the pure in herte: for they shall se God.

8 Blessed are the pure in heart: for they shall see God.

9 Blessed are the peacemakers: for they shalbe called the children of God.

9 Blessed are the peacemakers: for they shall bee called the children of God.

persecucion for rightwesnes sake: for theirs ys the kyngdome of heuen.

persecuted for righteousnesse sake: for theirs is the kingdome of heauen. (Crystal, p. 59)

In the Modern English, there are New English Bible which was published

in 1970, Good News Bible that was published in 1976, and New International

Version which was published in 1979. In addition, in 1982, the King James

Version was revised and published as New King James Version.

6. The sound system of English

According to Crystal (2003: 236-243) when the alphabet of English was first

devised, its letters were based on the nature of the sounds in the Old English.

However, there are differences between the written language and the spoken

language. In the English alphabet, there are five vowels (A, E, I, O, U). In fact,

there are about 20 vowels in most accents of English. In the table below are the

vowels that are introduced by the British phonetician A. C. Gimson .

The, butter, sofa, about ə Ape, waist, they, say eɪ Time, cry, die, high aɪ Boy, toy, noise, voice ɔɪ So, road, toe, know əʊ Out, house, how, found aʊ, ɑʊ Deer, here, fierce, near ɪə Care, air, bare, bear eə Poor, sure, tour, lure ʊə (Crystal, p. 237)

If we look at the table above, there are twelve pure vowel. It is evident that five of

them are relatively long and the other seven are relatively short. The contrast

between long and short vowel is not just one of length (quantity) but also the

different place of articulation (quality). This is why Gimson, in his transcription

gives different symbols to these pairs of vowel (/i:/ vs /ɪ/,etc.). Length-wise, the

diphthongs are like long vowels, but the first part of the diphthong in English is

much longer and louder than the second.

On the other hand, the different between consonants in the English alphabets

and sound system is less significant. There are 21 consonant letters in the written

alphabet and there are 24 consonant sounds in most English accents. However,

because of the erratic history of English spelling, in several cases, one consonant

sound is spelled by more than one letter or one consonant letter symbolizes more

than one sound. In the table below are the consonants introduced by A. C.

Gimson

Table 5: The list of consonants in the English sound system introduced by

The writing system is the representation of the spoken language. To reduce

the spoken language into the written one, spelling is needed. The spoken language

develops more rapidly than the written one because writing is permanent while

English in order to know more about the history of English language and its problems

to answer my first question, what the spelling of Early Modern English is like as seen

in the King James Version 1611.

The writing system and the alphabet have a close relationship with each other.

To learn the spelling of Early Modern English, of course, I must also learn what kind

of alphabet which that era had. In addition, it also helps me to answer my first and

second question, how it is different from Modern English.

Before the renaissance era, the official language for education and printed

books were Latin. Many people were influenced by Latin especially scholars, authors

and translators. Therefore, whenever they had to decide the spelling themselves, they

used some of Latin spellings. In this respect, learning Classical Latin is useful to

answer my first question.

Every result has a cause. So does the differences between the spelling of the

Authorized Version and the New King James Bible. In order to understand it, we must

look back to the history of holy bible. Therefore, learning the history of the

Authorized Version is necessary. It is also useful to answer my first question since the

data come from the Holy Bible.

The writing system and the sound system is related each other. Therefore, I

18

CHAPTER III METHODOLOGY

A. Object of the Study

My object of the study is the spelling of Early Modern English. According to

Cable and Baugh (1978: 199) the Early Modern English is the period of the English

language between the end of Middle English (the second half of 15th century) to the

beginning of Modern English. However, I just take the spelling because at that time

the spelling had not standardized yet. I would like to know what the spelling of Early

Modern English period like and how it is different from Modern English spelling.

I obtained the data from King James Version Holy Bible. King James Version

Holy Bible was translated in 1611 by 54 experts that worked in the 6 different groups.

Therefore, King James Version Holy Bible was included in the Early Modern English

period. In 1982, it was revised and published as the New King James Version and is

still used until now. It is a very famous Holy Bible which has become the source of

translation of the other Holy Bible in many languages. I retrieved King James Version

Holy Bible from <www.e-sword.net> that was published by Rick Meyer in January

2000.

B. Method of the Study

My research is a desk research. I took my primary data from King James

the differences of the spelling of King James Version 1611 by comparing it with the

New King James Version.

C. Research Procedure

1. Gathering the data

I took the primary data, King James Version 1611 and also some other Holy

Bibles such as Latin Vulgate Bible, and New King James Version. I needed those

Bibles to help my analysis.

Firstly, I read the King James Version 1611, and then if I found a word in the

Bible which had different spelling from Modern English standard spelling, I

looked for that word in the other Bibles that I had mention before.

2. Gathering the theories

The first step to gather the theories was thinking what theories that I needed.

After that, I went to the library or searched in the internet the theories that I had

thought about. After I got the theories, I filtered them. I took the fit ones with my

analysis and kept the others in order to make me easier if one of the unfit theories

actually was a theory that I needed in my analysis.

After that, I put them in a list to help my analysis later.

3. Analysis

In the first step of my analysis, I checked my list of differences that I made

when I was gathering the data. After that, based on the theory of Early Modern

Classical Latin Spelling, the History of the Holy Bible in English, the Sound

System of English, I made my analysis to describe the differences between the

Early Modern English and the Modern English to answer my first problem how

the spelling of the Early Modern English is different from the spelling of Modern

English. The last step was identifying the pattern of the spelling of the Early

Modern English to answer my second problem what the spelling of Early Modern

English is like as seen in King James Version 1611 Holy Bible.

4. Conclusion

After I had done with the analysis, I made the conclusion of my analysis.

5. Writing the thesis

After all of those steps above had been done, I started to write my thesis in

21

CHAPTER IV ANALYSIS

According Menyingkap Alkitab (2005: 8), the Authorized Version Holy Bible

or well known as the King James Version was translated in 1607 by 54 experts who

were grouped into six sections. Each section translated some bibles. It was published

in 1611 to replace the Geneva Bible. The King James Version was translated from

Septuagint. However, it was influenced by Tyndale’s New Testament. The King

James Version is a great text of the Early Modern English. Due to the time of the

translation, of course, there are differences between the English of the King James

Version and today’s English because the spelling at that time was unstable. Fromkin

and Rodman said that every author had his own spelling. Not only that, but

sometimes an author wrote a word differently such as Shakespeare who wrote the

first singular pronoun as I, ay, and aye (2003: 563). There are so many differences in

spelling that the Church had to revise it in order to be able to be read by people

nowadays. This revision is called as the New King James Version. What I analyzed

here were the differences of the Early Modern English spelling from the Modern

English one based on the King James Version especially the Gospel of Luke. I have

two problems. They are how the spelling of Early Modern English is different from

Modern English and what the spelling of Early Modern English is like as seen in

After I collected the data, I found that there are many differences between the

King James Version 1611 and the New King James Version. The differences are the

letter addition 2.4%, the apostrophe ‘s addition 1%, the change of consonant orders

0.02%, letter deletion 40.8%, doubled letters 2.7%, grammar shifts 0.06%, compound

differences 1.7%, negative morpheme shifts 0.04%, singled letters 8.6%, word

adaptation 0.06%, the letter shifts 42.48%, and misspellings 0.1%.

To explain the differences between the Early Modern English and Modern

English, I used the italic letter. For example a to explain the letter a.

A. The Letter Addition

The letter addition means a letter which did not exist in the King James

Version 1611 but existed in the New King James Version. There are many kinds

of letter addition that build the differences list of the King James Version 1611

and the New King James Version although the total of the letter addition is just

2.5%. They are the addition of the character a, b, c, d, e, g, h, i, m, p, t, u. The

most common of the letter addition is the addition of the e. Now, I will discuss it

from the a.

1. The addition of a

The addition of a usually used in the Latin name of people such as in table 1:

Table 1: The addition of a before e in the Latin names of people

No. King James Version 1611 New King James Version

1. Alpheus Alphaeus

2. Cesar Caesar

In the table above, a is added before e although the pronunciation is the same.

However, the addition of a not only in the Latin names of people but also the Latin

names of places such as Iudea in the King James Version 1611 which is spelled as

Judaea in the New King James Version. The same as the one for people, a is added

before e.

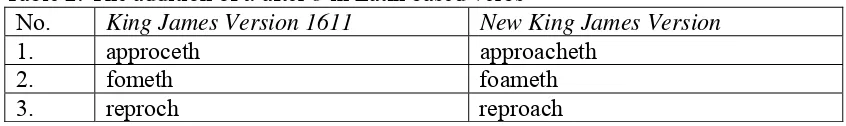

The character a is also added after o in some Latin based verbs such as in the

table 2:

Table 2: The addition of a after o in Latin based verbs

No. King James Version 1611 New King James Version

1. approceth approacheth

2. fometh foameth

3. reproch reproach

The addition of a after e is also used in some foreign origin verbs including

Latin as such as in the table 3:

Table 3: The addition of the character a after the character e in foreign origin verbs including Latin

No. King James Version 1611 New King James Version

1. clensed cleansed

2. vnleuened unleavened

In the table 3, both of them undergo the addition of a after e. However, not only the

verbs but also the noun such as years in the New King James Version was spelled as

yeres in the King James Version 1611.

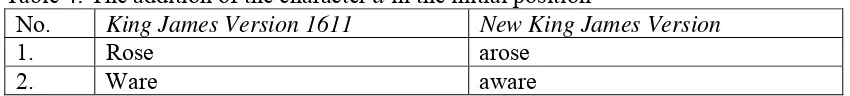

The last kind of the addition of a is the addition in the initial position. Look at

Table 4: The addition of the character a in the initial position

No. King James Version 1611 New King James Version

1. Rose arose

2. Ware aware

The characteristic of this kind of addition of a is that actually without a is added the

verbs already have meaning and add a change its meaning from doing something

without the outsider influence into doing something because of the outsider influence

for example the sentence you rose from a chair means you got up from a chair by

yourself while the sentence the problem arose means there was something that make

the problem .

2. The addition of b

The b which is added here is the silent b. According to Fromkin and Rodman

(2003:563), the reason why the silent b is added in the spelling is because the

scholars made the standard spelling based on the etymology. Before that, the spelling

of those words with the silent b based on their pronunciation. Look at the table below:

Table 5: The addition of the silent b

No. King James Version 1611 New King James Version

1. climed climbed

2. crummes crumbs

3. detters debtors

In the table above, the King James Version 1611 did not use the silent b because there

is no b in the pronunciation of those words while the New King James Version uses b

3. The addition of c

The same as point number 2, the c which is added here is the silent c. It is

usually added before k such as in the table below:

Table 6: The addition of c

No. King James Version 1611 New King James Version

1. striken stricken

2. stroke struck

In the table above, striken is spelled as stricken in the New King James Version and

stroke is spelled as struck in the New King James Version. How o is replaced by u

will be explained in the letter shifts o to u.

4. The addition of d

There was just one word that underwent the addition of d in the Gospel of

Luke. That is kinred. In the New King James Version, it is spelled as kindred.

5. The addition of e

There are many kinds of addition of e. However, the most common one is the

addition before r. For example in the table 7:

Table 7: The addition of e before r

No. King James Version 1611 New King James Version

1. entreth entereth

2. cumbred cumbered

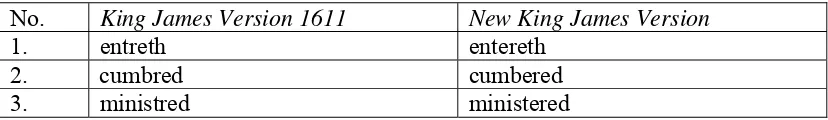

3. ministred ministered

In the table 7 above, in King James version 1611, before r there is not any e, but then

in the New King James Version, e is added there. The reason is that the translators of

pronounced as [ə]. Therefore, they omitted the e. However, after the spelling is

standardized, people choose to spell the weak e to conform the infinitive of those

words. Because of that, in the New King James Version enter + eth is spelled as

entereth instead of entreth.

With the same reason as the one before r, the addition of e before n occurred.

Therefore, in the New King James Version straiten + -ed is spelled as straitened

instead of straitned as in King James Version 1611.

The third form of the addition of e is the one after n. A little bit different with

the previous forms, the reason why in the King James Version 1611 it has been

omitted is because there is no need to keep the e since it does not change the

pronunciation. However, in the Modern English, to conform it with the stem, the

word line + -age is spelled as lineage although line in the lineage is pronounced

differently from the word line.

The last form of the addition of e is the one after w in the word ought in the

King James Version 1611 that become owed in the New King James Version. Those

two words seems very different but since in the Early Modern English people did not

standardize the spelling of a word, it was normal that the spelling was

pronunciation-based. However, when English was standardized, the ou became ow since there was a

need of a consonant in a more than one letter word, gh was deleted since it was silent,

e was added since there is no word that consisted 2 letters and ended in w, and t was

6. The addition of h

The letter h is usually added after t in the ordinal number. Look at table 8 :

Table 8: The addition of h in the ordinal number

No. King James Version 1611 New King James Version

1. eight eighth

2. sixt Sixth

Although in the first example it is written as eight, the cardinal number, actually from

the grammar it is an ordinal number. The eight here actually has the same form with

second example sixt. However, because eight is ended with t, the ordinal and the

cardinal form are the same. The original verse is like this:

And it came to passe that on the eight day they came to circumcise the childe, and they called him Zacharias, after the name of his father. (King James Version 1611, Luke 1:59)

In the word day there is not in the plural form because eight is an ordinal number

instead of cardinal number. If it is a cardinal number, it will be the eight days instead

of the eight day.

7. The addition of i

There was just one word that underwent the addition of i in the Gospel of

Luke. That is surfetting. In the New King James Version, it is spelled as surfeiting.

8. The addition of m

In the Gospel of Luke there was just one word which underwent the addition

of m. It was fro. In the New King James Version, it is spelled as from. Actually fro

the phrase like to and fro which has the meaning to and from as stated in the Noah

Webster’s 1828 Dictionary.

Fro, adv. [In some languages it is a prefix, having the force of a negative.]

From; away; back or backward; as in the phrase, to and fro, that is, to and from, forward or toward and backward, hither and thither.

9. The addition of p

There was just a word in the Gospel of Luke that underwent the addition of p.

That was receit. Now, in the New King James Version, it is spelled as receipt. The p

there is the silent p. The reason why the scholars gave the addition of p in receit was

because the Latin word of receit is receptus. Therefore, although the p there is the

silent one, it is added to conform the etymology because the scholars who

standardized the English language tended to conform the etymology rather than the

pronunciation.

10.The addition of t

There were two version of how to spell midst in the King James Version 1611.

Those were middes and mids. However, the one which was more popular was mids.

However, t is added after s for both of them.

11. The addition of u

Usually, u is added after a vowel. Look at the table 10:

Table 10: The addition of u after a vowel

No. King James Version 1611 New King James Version

1. lanch launch

In the first example above, u is added after a and in the second example u is added

after o. However, there is an exception. For the word ghest-chamber, the addition of u

is after h instead of the vowel. In the New King James Version, it is spelled as

guestchamber.

B. The apostrophe ‘s addition

According to Dent (2003: xxxiii-xxxv), in Early Modern English there were

no orthographic distinction between simple plural, singular possessive or plural

possessive. It is because there had not been any apostrophe ‘s addition yet. Therefore,

sisters, sister’s, and sisters’ were spelled the same, sisters. Look at the table below:

Table 11: The apostrophe ‘s addition

No. King James Version 1611 New King James Version 1. centurions centurion’s

2. Dauids David’s

In table 11, the genitive s is spelled without the apostrophe. It is because in the Early

Modern English apostrophe was not commonly used.

C. Change of Consonant Orders

Some of Early Modern English words had different letter order from the

Modern English one. In the Gospel of Luke, I found one of them that is cattle which

was spelled as cattell in King James Version 1611. It is because the translators of

D. Letter Deletion

Letter deletion means a letter which existed in the King James Version 1611

but did not exist anymore in the New King James Version. The letter deletion has the

second greatest portion of the difference of spelling between the King James Version

1611 and the New King James Version. That is 40.8%. It also has the most common

difference of spelling, that is the deletion of e. There are many kinds of the letter

deletion. Those are the deletion of a, c, e, h, i, o, s, st, u.

1. The deletion of a

The deletion of a which I found in the Gospel of Luke is the deletion of a after

the vowels. The most common vowel is e. Look at table 12:

Table 12: The deletion of a after e

No. King James Version 1611 New King James Version

1. prease press

2. shepheards shepherds

In the first example, a is deleted because the scholars conformed press with its

etymology pressus while the second example, there is no hint why they dropped a.

The second kind of the deletion of a is the deletion of a after o. It is a unique

case since the King James Version 1611 spelled cloake which is almost the same with

Modern English spelling while the New King James Version spelled it cloke which

2. The deletion of c

There was just one word which underwent the deletion of c. That is bancke

which in the New King James Version is spelled as bank. The c there was deleted

because it was silent c. Therefore, there is no need to keep it.

3. The deletion of e

The deletion of e is the most common cause of difference of spelling between

the King James Version 1611 and the New King James Version. It has 39.6%.

Traditionally, e comes from the Semitic alphabet. Unlike u and i which have 2

variants, e does not have such variant. In constructing the words, e often has no

function and just being the silent e. According to Cable and Baugh (1978: 212),

Mulcaster in his book Elementarie used e for words ending in ss. Otherwise, a final e

is used to indicate a preceding long vowel, and at the end of words ending in the

sound v or z.

The same as Mulcaster’s Elementarie, the translators of King James Version

1611 used for words ending in ss. Look at the table below:

Table 13: The deletion of e after -ss

No. King James Version 1611 New King James Version

1. blesse bless

2. passe pass

In the table 13, the word bless is spelled as blesse in the King James Version 1611

ending in other consonant. For example the words ending in the sound [m] with the

spelling mb. Look at the table 14:

Table 14: The deletion of e after -mb

No. King James Version 1611 New King James Version

1. hony combe honeycomb

2. wombe womb

In the table 14, the word honeycomb, which is pronounced as [’hʌnikəʊm] was

spelled as hony combe in the King James Version 1611 and in the second example,

the word womb, which is pronounced as [wu:m] was spelled as wombe in the King

James Version 1611.

The other silent e is in the end of the words ending with nd. Look at table 15:

Table 15: The deletion of e after -nd

No. King James Version 1611 New King James Version

1. hande hand

2. kinde kind

In the examples above, hand and kind were spelled as hande and kinde in the King

James Version 1611. The other example is the word mind which is spelled as minde

in King James Version 1611 (Luk 1:29).

The silent e also occurs in the words ending with f as seen in table 16:

Table 16: The deletion of e after -f

No. King James Version 1611 New King James Version

1. deafe deaf

The underlined words, deaf and himself were spelled as deafe and himselfe. The same

as mbe which is pronounced as [m] or nde which is pronounced as [nd], fe is always

pronounced as [f].

There is still the other consonants which is followed by the silent e. They are

k, l, m, n, p, r, and t. Look at the examples below:

Table 17: The deletion of e after k, l, m, n, p, r, t

No. King James Version 1611 New King James Version

1. drinke drink

2. soule soul

3. kingdome kingdom

4. sonne son

5. keepe keep

6. feare fear

7. hoste host

In the Early Modern English era, people tended to use the silent e in the final

position after the letter k, as in my first example in table 17. The word drink was

spelled as drinke in the King James Version 1611. In the King James Version 1611,

not only the word drink which was spelled with the silent e, but also the word back

which was spelled as backe and speak which was spelled as speake. However,

nowadays many of the silent e were eliminated, just a few remain the same. Now, in

Modern English, people use the silent e to indicate the preceding diphtongs. For

example the word make, and bake or spoke and yoke.

As in my second example in the table 17, the silent e was also used in the final

The words which contained double l (ll) were not followed by the silent e. See the

following table:

Table 18: The comparison of The King James Version 1611 and The New King James Version in the spelling of the words ended by -ll

King James Version 1611 New King James Version

1. And the childe grew, and waxed strong in spirit, and was in the deserts, till the day of his shewing vnto Israel. (Luk 1:80)

1. And the child grew, and waxed strong in spirit, and was in the deserts till the day of his shewing unto Israel. (Luk 1:80)

2. Then said hee also to him that bade him, When thou makest a dinner or a supper, call not thy friends, nor thy brethren, neither thy kinsemen, nor thy rich neighbours, lest they also bid thee againe, and a recompence be made thee. (Luk 14:12)

2. Then said he also to him that bade him, When thou makest a dinner or a supper, call not thy friends, nor thy brethren, neither thy kinsmen, nor thy rich neighbours; lest they also bid thee again, and a recompence be made thee. (Luk 14:12)

In table 18, both of till and call have the same spelling in the King James Version

1611 and the New King James Version. It is because both of them are ended by

double l. The other examples are will and shall which have the same spelling both in

the King James Version 1611 and the New King James Version.

Next, in table 17, the silent e was also used after the word ending with m. The

word kingdom was spelled as kingdome in the King James Version 1611. In the

Modern English era, the same as the silent e after k, the silent e after m was also

deleted. Just a few remain the same. Usually the silent e which remains the same was

in the words which will change if their silent e were taken. For example, the word

came [keɪm], if we take the silent e, it probably will pronounce as [kæm]. Therefore,

The occurrence of the silent e after n is almost the same as the occurrence of

the silent e after the other letters. As in the table 17, the word son was spelled as

sonne in the King James Version 1611. Its occurrence is random. However, usually it

does not occur after the letter en, an, ion, in function words, and some proper name

such as a person name. However, proper name like Jordan was spelled as Iordane,

and Samaritan was spelled as Samaritane. Look at the table below:

Table 19: The comparison of The King James Version 1611 and The New King James Version in the spelling of the words ended in n

King James Version 1611 New King James Version

1. And they had no childe, because that Elizabeth was barren, and they both were now well striken in yeeres. (Luk 1:7)

1. And they had no child, because that Elisabeth was barren, and they both were now well stricken in years. (Luk 1:7)

2. And when they found not his bodie, they came, saying, that they had also seene a vision of Angels, which saide that he was aliue. (Luk 24:23)

2. And when they found not his body, they came, saying, that they had also seen a vision of angels, which said that he was alive. (Luk 24:23)

3. And Iesus answering, said vnto them, They that are whole need not a physician: but they that are sicke. (Luk 5:31)

3. And Jesus answering said unto them, They that are whole need not a physician; but they that are sick. (Luk 5:31)

4. And it came to passe that when Elizabeth heard the salutation of Marie, the babe leaped in her wombe, and Elizabeth was filled with the holy Ghost. (Luk 1:41)

4. And it came to pass, that, when Elisabeth heard the salutation of Mary, the babe leaped in her womb; and Elisabeth was filled with the Holy Ghost: (Luk 1:41)

5. And many lepers were in Israel in the time of Elizeus the Prophet: and none of them was cleansed, sauing Naaman the Syrian. (Luk 4:27)

5. And many lepers were in Israel in the time of Eliseus the prophet; and none of them was cleansed, saving Naaman the Syrian. (Luk 4:27)

In my first example in table 19, barren and striken which are ended with en were

without the silent e in the King James Version 1611. In my third example, the word

physician as well as man and woman are spelled the same both in the King James

Version 1611 and the New King James Version. In the fourth example, the function

word in was spelled without the silent e because they usually did not add the silent e

for the function words. The proper name such as Naaman (person’s name) and Syrian

(nationality) were also spelled without the silent e in the King James Version 1611

although there are exceptions such as Iordane (Jordan) and Samaritane (Samaritan).

The next consonant followed by the silent e is p. Usually the silent e follows p

if there is a long vowel like the diphthongs and the sound [i:], such as my example in

table 17, the word keep was spelled as keepe in the King James Version 1611. While

the short sounds usually are not followed by the silent e except help and sup which

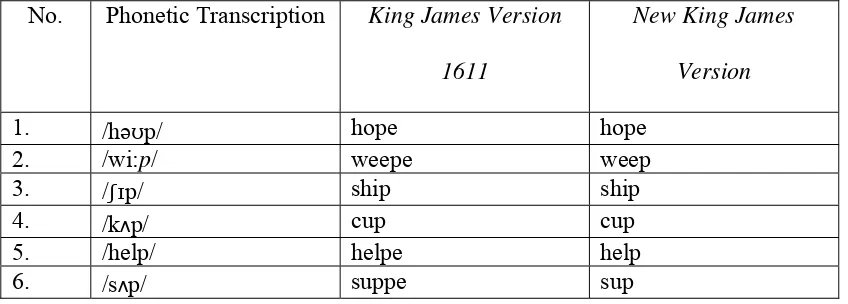

were spelled as helpe and suppe in the King James Version 1611. Look at table 20:

Table 20: The comparison of The King James Version 1611 and The New King James Version in the spelling of the word ending with p

No. Phonetic Transcription King James Version

1611

New King James

Version

1. /həʊp/ hope hope

2. /wi:p/ weepe weep

3. /ʃɪp/ ship ship

4. /kʌp/ cup cup

5. /help/ helpe help

6. /sʌp/ suppe sup

In the table above, my first example proves that p preceded by the diphthong is

it distinguishes between hop [hɒp] and hope [həʊp]. In the second example there is

weepe (weep) which is pronounced as [wi:p]. Both of the first and the second

examples are the long or tense sound. Therefore, they were followed by the silent e in

the King James Version 1611. In the other hand, the third and the fourth examples are

pronounced with the short or lax vowel. They are ship [ʃɪp] and cup [kʌp]. Both of

them were not followed by the silent e in the King James Version 1611. However, in

my fifth and sixth examples the short vowel were followed by the silent e. The reason

is unclear why the short vowel such as help [help] and sup [sʌp] followed by the

silent e in the King James Version 1611.

The next consonant which was usually followed by the silent e is r. As in the

table 17 example number 6, fear was spelled as feare in the King James Version

1611. The occurrence of r followed by e is determined by the vowel preceding r. The

r followed by the silent e usually is preceded by [ɪə], [eə], [ɔ:] except the word for

since a function word was not followed by the silent e, [ə] which is spelled as u, and

[ɑ:]. Look at the table below:

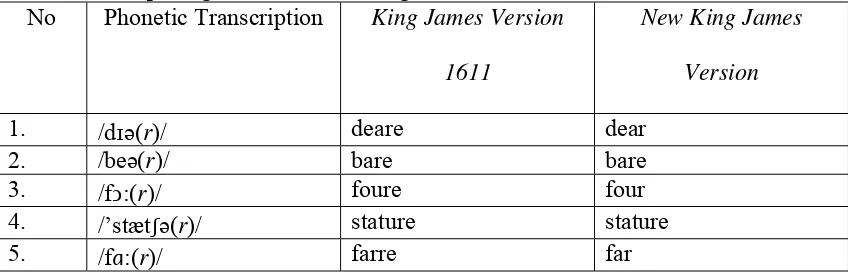

Table 21: The comparison of The King James Version 1611 and The New King James Version in the spelling of the words ending with r

No Phonetic Transcription King James Version

1611

New King James

Version

1. /dɪə(r)/ deare dear

2. /beə(r)/ bare bare

3. /fɔ:(r)/ foure four

4. /’stætʃə(r)/ stature stature

In the table above, the word dear [dɪə(r)] was spelled as deare in the King James

Version 1611. Usually [ɪə] was spelled as ea in the Early Modern English although

some words had different spelling like the word year which was spelled as yeere in

the Early Modern English. In the second example, the word bare remains the same in

the Modern English era. The silent e here is for distinguishing bare [beə(r)] from bar

[bɑ:(r)]. The third example talks about the sound [ɔ:]. Except the word four which

was spelled as foure in the King James Version 1611, the others have the same

spelling for both Early Modern English and Modern English such as bore and more.

The next is the word stature. It has the same spelling for both the King James Version

1611 and the New King James Version. However, not all r preceded by [ə] followed

by the silent e. The one which followed by the silent e is the [ə] which is spelled as u.

If other than that, it will not be followed by the silent e such as in the table 22:

Table 22: The comparison of The King James Version 1611 and The New King James Version in the spelling of the words ending in r which is preceded by the sound /ə/

King James Version 1611 New King James Version

1. And Iesus increased in wisedom and stature, and in fauour with God and man. (Luk 2:52)

1. And Jesus increased in wisdom and stature, and in favour with God and man. (Luk 2:52)

2. And this rumour of him went foorth throughout all Iudea, and throughout all the region round about. (Luk 7:17)

2. And this rumour of him went forth throughout all Judaea, and throughout all the region round about. (Luk 7:17)

From the table 22, we can see that in the King James Version 1611, favour [’feɪvə(r)]

and rumour [’rumə(r)] were spelled without the silent e although they had sound [ə]

The last example in the table 21 is far [fɑ:(r)] which was spelled as farre in

the King James Version 1611. The characteristic of this type is the r which was

doubled. The other word which used this type is afar which was spelled as afarre in

the King James Version 1611.

The last consonant that we talked about in table 17 was t. The words ending

with t usually will be followed by the silent e if their vowels are long vowels

including diphthongs. As in the table 21 host was spelled as hoste in the King James

Version 1611 because it is pronounced as [həʊst]. On the other hand, if the vowels are

short vowels they usually will not be followed by the silent e just as this table 23:

Table 23:The comparison of The King James Version 1611 and The New King James Version in the words ending with t which have the short vowels

No. Phonetic Transcription King James Version

1611

New King James

Version

1. /pʊt/ put put

2. /set/ set set

As in the table above, put [pʊt] and set [set] are not followed by the silent e. It is

because they have short vowels. However, although usually it is distinguished by the

length of the vowel, there are exceptions. The words which have affricative sounds

before t are not followed by the silent e except host and haste which were spelled as

hoste and haste in the King James Version 1611 because they have diphthong vowels.

s) were not followed by the silent e in the King James Version 1611. Look at the table

below:

Table 24: The comparison of The King James Version 1611 and The New King James Version in the words ended in t which contain the affricative sounds

King James Version 1611 New King James Version

1. And he stood ouer her, and rebuked the feuer, & it left her. And immediatly she arose, & ministred vnto them. (Luk 4:39)

1. And he stood over her, and rebuked the fever; and it left her: and immediately she arose and ministered unto them. (Luk 4:39)

2. There was in the dayes of Herode the king of Iudea, a certaine Priest, named Zacharias, of the course of Abia, and his wife was of the daughters of Aaron, and her name was Elizabeth. (Luk 1:5)

2. There was in the days of Herod, the king of Judaea, a certain priest named Zacharias, of the course of Abia: and his wife was of the daughters of Aaron, and her name was Elisabeth. (Luk 1:5)

In the table above, the second example, priest is not followed by the silent e although

it has long vowel [i:]. However, the first example is ambiguous. It is unclear that it

was not followed by the silent e because of its affricative sounds or its short vowel or

even both of them. Unfortunately, in the King James Version 1611 there were just

two words contain f which were ended with t. They are lift and left. Both of them

have the short vowels. Therefore, I lacked of proofs to prove my analysis.

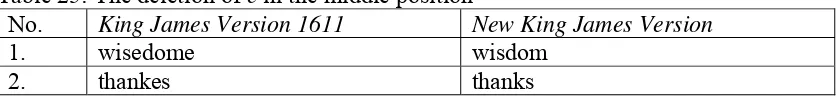

The deletion of e does not always occurred in the final position. In the Early

Modern English, sometimes it could be in the middle position. There is a possibility

that the pronunciation of the words contain the silent e in the middle position in Early