Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 11 January 2016, At: 22:17

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

Does Economics Education Make Bad Citizens? The

Effect of Economics Education in Japan

Yoshio Iida & Sobei H. Oda

To cite this article: Yoshio Iida & Sobei H. Oda (2011) Does Economics Education Make Bad Citizens? The Effect of Economics Education in Japan, Journal of Education for Business, 86:4, 234-239, DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2010.511303

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832323.2010.511303

Published online: 21 Apr 2011.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 88

ISSN: 0883–2323

DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2010.511303

Does Economics Education Make Bad Citizens? The

Effect of Economics Education in Japan

Yoshio Iida and Sobei H. Oda

Kyoto Sangyo University, Kyoto, Japan

Does studying economics discourage students’ cooperative mind? Several surveys conducted in the United States have concluded that the answer is yes. The authors conducted a series of economic experiments and questionnaires to consider the question in Japan. The results of the prisoner’s dilemma experiment and public goods questionnaires showed no differences between the behaviors of economics majors and nonmajors. The uniqueness of economics majors was found in their answers to questions concerning whether they behave honestly if they pick up money. The percentage of economics majors who said that they behave honestly was significantly lower than that of students in other disciplines.

Keywords: economics education, experimental study, noncooperative games, questionnaire survey, rational behavior

Economics students learn that in standard economics theory, individuals are supposed to be rational or, in other words, selfish. Repeatedly dealing with such an idea in economics classes may lead students to believe that this is a matter of course, and thus induce them to change their actual behavior to selfish, even if it then conflicts with social profit. Does studying economics discourage cooperative behavior of stu-dents? This is a serious question for educators in economics.

Literature Review

Since the 1980s, several research studies in the United States have, using experimental or questionnaire investigation, pro-vided answers to the question whether economics educa-tion discourages students’ cooperative behavior. Marwell and Ames (1981) found that graduate students of economics contributed significantly less than other student groups in a public-goods experiment. Carter and Irons (1991) found that undergraduate students of economics were more selfish in an ultimatum bargaining game because they accepted less and kept more. Frank, Gilovich, and Regan (1993) investigated the students’ behavior in a prisoner’s dilemma game, and found that the decisions were correlated with a student’s ma-jor, sex, and years at university and that the economics majors defect more frequently. Seguino, Stevens, and Lutz (1996)

Correspondence should be addressed to Yoshio Iida, Kyoto Sangyo University, Department of Economics, Motoyama, Kamigamo, Kita, Kyoto 6038555, Japan. E-mail: iida01@cc.kyoto-su.ac.jp

observed students’ behavior in a public-goods experiment. Although the influence of academic majors was not signifi-cant, the study found a positive correlation between number of economics classes completed by the economics majors and free riding. Cox (1998) conducted questionnaire investiga-tions that asked about participants’ choices in a public-goods experiment and in actual situations that were similar to the experiment. However, with questions that ask how much tip to leave in a restaurant and whether an individual voted in the last election, there were no significant differences between the economics majors and others. In response to a question about cooperating in saving water during a water shortage as well as a question asking about the distribution of the amount of investment in public goods and private goods in the public-goods game, however, economics majors were more selfish than the others. Though some of them had prob-lems in controlling the experimental conditions, these results are identical to those of the well-designed studies. According to an experimental research by Seguino et al. and the ques-tionnaire research by Frank et al., the reason for this is not that selfish individuals major in economics, but that students are influenced by studying and considering mainly the view of the rational decision making.

Is it plausible that studying economics creates a selfish social citizen? Yezer, Goldfarb, and Poppen (1996) provided interesting counterevidence. They designed a lost-letter ex-periment in which envelopes containing cash were dropped in classrooms, and the return rate of the envelopes was used as a measure of cooperation. The results showed that the

DOES ECONOMICS EDUCATION MAKE BAD CITIZENS? 235

return rate of the students in the economics class was higher than that of the students in other classes. Frank, Gilovich, and Regan (1996) criticized this result because a field ex-periment cannot control various factors, unlike a laboratory experiment. The result is, therefore, not necessarily produced by a factor that the experimenter set out to study. To inter-pret this result, Zsolnai (2003) focused on the difference in the experimental design concerning monetary profit. In a laboratory experiment, the subjects receive rewards from experimenters; thus, no subject has any property in the be-ginning. However, Yezer et al.’s study the subjects have a reason to believe that the money they picked up is someone else’s property. Zsolnai argued that the lost-letter experimen-tal results reveal whether the involved individuals respect the property rights of the envelope’s owner.

Research Question

The research question of this study is whether the tendency of selfish choice of economics majors is also found in Japan. As described previously, although there is room for further investigation of the explanation of the field experiment re-sults, many laboratory experimental studies have found that economics students are more selfish than noneconomics stu-dents. However, there is room for an examination of whether this can also be applied to students in other countries.

Some researchers have proved that cultural differences produce different results in the same experiments (e.g., Ca-son, Saijo, & Yamato, 2002). Japan has a more collective culture than the United States, and such cultural differences may affect the influence of economics education on students. Labor market customs may also affect students’ choice of major and how devoted they are to learning. In Japan, the university grade is the most important factor in achieving success in job hunting. High school students struggle to en-ter a higher grade university, and their choice of major is of only secondary importance. Such a social background might make students less enthusiastic about their major and reduce the effects of their education.

This study establishes whether the effect of economics education is found in Japan, despite the social and cultural differences described previously, using a simple experimen-tal study and questionnaires.

METHOD

Outline of the Investigation

The experiment and questionnaire survey were conducted in an experimental economics laboratory at our university in Japan. Subjects were assigned seats divided by separators and a computer on which they performed decision-making experiments and completed the questionnaires. The experi-ment was programmed by and conducted using z-Tree soft-ware (Fischbacher, 2007). The subjects were first- to

fourth-TABLE 1

Payoff Matrix of the Prisoner’s Dilemma Game

Player B

year students in various university departments (economics, business administration, cultural studies, engineering, for-eign languages, law, and computer science). The total number of participants was 399.

Experimental Study

The experiment we conducted was the prisoner’s dilemma game. The payoff matrix is shown in Table 1. To avoid fram-ing effects, we named the choices C and D in place of cooation and defection. The subjects were paired randomly, per-formed the experiment anonymously, and received between

100 (US$1) and400 (US$4), depending on the

exper-imental results. No communication was allowed during the experiment. The experimenter distributed the instructions for the experiment and read them out from a paper copy (copies are available upon request), and also examined subjects in the rules of the game on the computer. The experiment began after all participants had answered the examination questions correctly. The subjects inputted the choice C or D from their computer terminal.

Questionnaire Investigation

After the subjects had input their decision, they were asked to answer eight questions on the same computer, as shown in Table 2. The result of the experiment was not revealed to the subjects until they had completed this stage of the ques-tionnaire. The subjects were informed that there was no pay-off for the questionnaire survey. The questionnaire contained two sections. One section contained questions about honesty, which asked whether subjects thought they (or another per-son) would behave honestly if they (or another perper-son) had a chance to take advantage of someone else’s mistake. The other section contained questions on a public-goods problem in which acting selfishly is individually optimal, but the so-cial optimal fails. These contents of the questionnaire were identical to those of Frank et al. (1993) and Cox (1998). Af-ter completing the questionnaire, the subjects inputted their grade, age, and sex. The number recorded for each question was identical to that of the experiment (N=399), except for the question about voting (N=201), as the students under 20 years at age did not yet have the right to vote.

TABLE 2 Questionnaires

The owner of a small business is shipped ten microcomputers but is billed for only nine. A1: Do you think the owner will inform the computer company of the error? A2: Will you inform the computer company of the error, if you were the owner?

You lost a envelope containing 100,000 yen. Your name and address were written on it. B1: Do you think that a stranger who picked up the envelope will return it to you? B2: If you were the person who picked up the envelope, will you return it to the owner?

C1: Did you vote in the most recent election?

C2: Because of a water shortage, your city government has requested that all residents place one large brick in the tank of every toilet in their house or apartment. Placing objects in the toilet reservoir reduces the amount of water used with each flush but also reduces flushing effectiveness. Would you comply with this voluntary request?

D1: When you travel abroad, you treat yourself and three of your friends to dinner at a popular restaurant. The total bill is$56. Your waiter/waitress provided personable and effective service. How much of a tip would you leave?

D2: Assume that you have 10,000 yen that you must invest for 1 year at least one of two assets. All other members of the subjects in the class also have 10,000 yen. You may divide your money between the two assets in any way you choose. Asset A pays a fixed return of 5%. Asset B pays a return of 10% on all invested funds. This total return is then split equally among all members of the class. For example, in a class of 20 students, if a total of

100,000yen is invested in Asset B, then the total return will be 10,000 yen (100,000 yen×0.1). This 100,000 yen will then be split evenly among all 20 students. (100,000 yen/20=5,000 yen) regardless of whether they invested in Asset B. How much will you invest in Asset B?

RESULTS

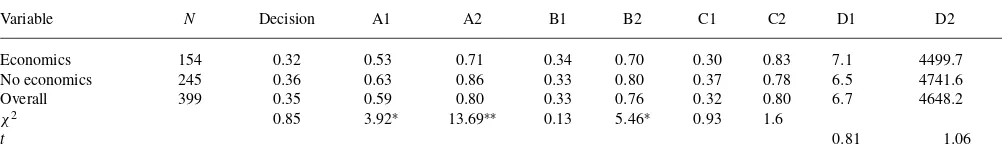

Results of Experimental Study

Comprehensive observations are shown in Table 3. In the prisoner’s dilemma experiment, 31.8% of the 154 economics students chose cooperation. Although this rate was slightly lower than that of the 245 noneconomics students (36.3%), the difference was not statistically significant: χ2(1, N =

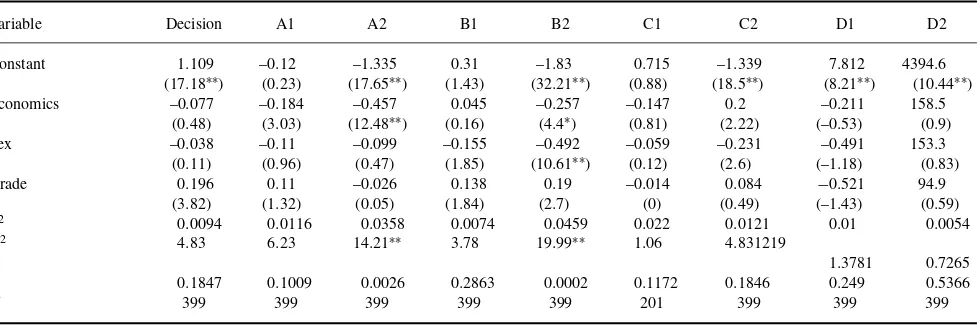

399)=0.854,p=.36. However, as past research has pointed out, years at university and gender might also have affected the result. Table 4 shows the result of the nominal logistic fit regression that took these factors into consideration. The result shows that although economics majors and men are more likely to betray others, both explanatory variables are not statistically significant. There was no significant differ-ence between the economics and noneconomics students in the data on the first-year students. That is, the tendency of self-selection that Carter and Irons (1991) discovered in an ultimatum game was not seen in the prisoner’s dilemma game in Japan.

Results of Questionnaire Survey

Some questions regarding honesty showed significant differ-ences between economics majors and nonmajors. In question A1, about 53% of economics students answered that a busi-ness owner would behave honestly in a situation where he or she had an opportunity to take advantage of the other’s mistake, whereas 63% of other students answered that the owner would behave honestly. A chi-square test supported the significant difference, at 5% level, between economics and noneconomics students,χ2(1, N =399) =3.92, p =

.048. In question A2, 71% of economics students thought that they would behave honestly if they were the owner, whereas 86% of noneconomics students thought that they would behave honestly. This difference is also significant at 1% level,χ2(1,N=399)=13.690,p=.0002. The ratio of

students who think a stranger would return the lost envelope containing the money in question B1 is nearly equal (34% of economics students and 33% of the other students),χ2(1,N

=399)=0.130,p=.72. As compared to 80% of noneco-nomics students, 70% of econoneco-nomics students thought that

TABLE 3 Summary of Observations

Variable N Decision A1 A2 B1 B2 C1 C2 D1 D2

Economics 154 0.32 0.53 0.71 0.34 0.70 0.30 0.83 7.1 4499.7

No economics 245 0.36 0.63 0.86 0.33 0.80 0.37 0.78 6.5 4741.6

Overall 399 0.35 0.59 0.80 0.33 0.76 0.32 0.80 6.7 4648.2

χ2 0.85 3.92∗ 13.69∗∗ 0.13 5.46∗ 0.93 1.6

t 0.81 1.06

Note.The values in the decision column show the rate of cooperative decision making in the experiment, and the values in questionnaire columns of As, Bs, and Cs represent the rate of answer “yes,” and the D columns show the average of the number of subjects answered. Chi square andtvalues for the hypothesis that major and answers are dependent.

∗p=.05.∗∗p=.01.

DOES ECONOMICS EDUCATION MAKE BAD CITIZENS? 237

TABLE 4

Nominal Logistic Fit and Ordinary Regressions for PD Game and Questions

Variable Decision A1 A2 B1 B2 C1 C2 D1 D2

Constant 1.109 –0.12 –1.335 0.31 –1.83 0.715 –1.339 7.812 4394.6

(17.18∗∗) (0.23) (17.65∗∗) (1.43) (32.21∗∗) (0.88) (18.5∗∗) (8.21∗∗) (10.44∗∗)

Economics –0.077 –0.184 –0.457 0.045 –0.257 –0.147 0.2 –0.211 158.5

(0.48) (3.03) (12.48∗∗) (0.16) (4.4∗) (0.81) (2.22) (–0.53) (0.9)

Sex –0.038 –0.11 –0.099 –0.155 –0.492 –0.059 –0.231 –0.491 153.3

(0.11) (0.96) (0.47) (1.85) (10.61∗∗) (0.12) (2.6) (–1.18) (0.83)

Grade 0.196 0.11 –0.026 0.138 0.19 –0.014 0.084 −0.521 94.9

(3.82) (1.32) (0.05) (1.84) (2.7) (0) (0.49) (–1.43) (0.59)

R2 0.0094 0.0116 0.0358 0.0074 0.0459 0.022 0.0121 0.01 0.0054

χ2 4.83 6.23 14.21∗∗ 3.78 19.99∗∗ 1.06 4.831219

F 1.3781 0.7265

p 0.1847 0.1009 0.0026 0.2863 0.0002 0.1172 0.1846 0.249 0.5366

N 399 399 399 399 399 201 399 399 399

Note.Decisions were coded as 1 for cooperation and as 0 for betrayal. Responses of questions A1, A2, B1, B2, C1, and C2 were coded as 1 for “yes” and 0 for “no.” The independent variable “econ” equaled 1 for economics majors and 0 otherwise; “sex” equaled 1 if male and 0 otherwise; “grade” was 1 for freshmen, 2 for sophomores, 3 for juniors, and 4 for seniors. In parentheses areChisquares of coefficients (Decision, A1, A2, B1, B2, C1 and C2) and

t-values (D1 and D2).dfof eachChisquare is 3.Nof eachChisquare andt-value shown in bottom row of table.

∗p=.05;∗∗p=.01.

they would behave honestly if they picked up the envelope in question B2. The difference is significant at 5% level,χ2(1,

N=399)=5.46,p=.0195.

To test the impact on responses according to major, gender, and years at university, while holding other factors constant, we implemented the nominal logistic fit regression study shown in Table 4. Students who majored in economics were more likely to think that the business owner would be dis-honest than the other majors in question A1. However, after controlling the gender and years at university, the major was no longer significant at 5% level. On the other hand, in the regression studies of questions A2 and B2, the major was sig-nificant. The results show that economics students were more likely to say that they would behave dishonestly. Differences between economics majors and other majors are observed from the first to the fourth year, although the differences di-minish slightly as the years increase. This suggests that such a tendency to report oneself as dishonest is not nurtured by economics education.

In the public-goods questions, there are no significant dif-ferences at 5% level between economics majors and the other majors. In question C1, approximately 29% of 69 economics students answered that they had voted in the most recent elec-tion, compared to 36.4% of 132 other students, χ2(1, N=

201)=1.12,p=.29. In question C2, 83% of 154 economics majors answered that they would reduce water consumption, whereas 78% of 245 noneconomics majors said that they would cooperate, χ2(1,N =399)=1.6,p =.21. The

av-erage tip of the economics majors in question D1 was$7.1.

The other majors left a tip of$6.5,t(399)=0.81,p=.41. In question D2, economics students placed about4500 of their investment in the cooperative asset B, whereas the other students allocated 4742 yen of their portfolio to asset B,

t(399)=1.06,p=.29. The results of the regression studies

are shown in Table 4. There was no significant correlation between the responses to public-goods questions and major, nor was there a significant correlation for gender or years at university.

The structure of the public-goods problem is basically identical to the prisoner’s dilemma game in which acting selfishly is individually optimal but fails to produce a better payoff. However, the results of this study show that the sub-jects who cooperated or defected in the experiment tended not to choose the cooperative or noncooperative response, respectively, in the public-goods questionnaire. On the ques-tion of voting, 36.2% of the 69 subjects who cooperated in the experiment answered that they had voted, and 33.3% of the 126 subjects who defected answered that they had voted. The difference was not significant,χ2(1,N=201)=0.194,

p=.66. Out of 128 cooperators, 81.2% said that they would reduce water consumption, whereas 79.3% of 261 defectors said that they would comply. There was no significant dif-ference between them,χ2(1, N =399) =0.165,p =.68.

The answers of cooperators and defectors regarding tips and public assets were also not significantly different. Coopera-tors answered that they would leave$5.93 for a tip and invest 4950 in asset B. Defectors said that they would leave$7.13

for a tip and invest4412 in asset B, for the tip,t(399)=

1.49,p=.14; for the investment,t(399)=1.51,p=.13.

DISCUSSION

Conclusions

Our research drew no international conclusions on the effect of studying economics, or on the innate preferences of the students who major in economics, regarding the decisions

made in the prisoner’s dilemma game. Unlike the findings of the previous research performed in the United States, we found that economics majors in Japan were not more self-ish than the nonmajors. Although the Japanese economics majors were less cooperative in the prisoner’s dilemma ex-periment, the difference found was not significant, and the decisions observed had no significant correlation with years at university. Thus, we conclude that in Japan, economics ed-ucation does not induce students to make selfish decisions, and that a selfish individual does not necessarily major in economics.

These findings were observed in the experimental study of the prisoner’s dilemma with monetary payoff, and in the questionnaire survey that asked about the behavior of the subjects in similar situations. It is difficult to provide a per-suasive explanation of the difference between the results of the prior research in the United States and our research. One possible reason may be the difference in social culture. Individualists would prefer cost-benefit analysis because of their emphasis on market pricing and a tendency to rely on economic rationality in social exchanges (Leung and Tong, 2004). Compared with the United States, Japan has a less in-dividualist culture, and so students may be more reluctant to admit the idea of rational behavior. The other feasible reason concerns employment customs in Japan. Japanese companies seldom consider a student’s major important, except in cases where they recruit specialists such as engineers, researchers, chemists, and doctors. This is because many Japanese firms think that the education received in an office (e.g., on-the-job training) is much more important than the education received in schools. The academic level and results of a university stu-dent are, for Japanese companies, only a substitute index for the student’s learning ability. This may make students unen-thusiastic about their major, and make the effect of economics education on the students only minor.

It is important to note that the responses to the question-naires and the decisions in the experiments did not corre-spond with each other, although each person answered and made decisions at nearly the same time. One crucial differ-ence of the experimental study from the questionnaire survey was the existence of a real monetary reward. The monetary incentive may have distorted a social norm–oriented individ-ual’s preference to make an uncooperative choice. However, this incentive cannot explain why a cooperator in the experi-ment chose an uncooperative answer in the questionnaire, or why the ratios of the uncooperative answers of cooperators are nearly identical to those of the defectors. The other im-portant difference is that in the experiment, a subject plays a game against a single particular opponent, so the decision of the opponent is critical for the rewards. Such a condition might make the subjects concentrate on guessing their op-ponent’s decision but paying no attention to their own moral sense.

The uniqueness of economics majors in Japan is found in the questionnaire survey about honesty. In this survey, a

larger percentage of the economics majors than other ma-jors answered that they would take advantage of someone else’s mistake. A notable difference was found in first- to fourth-year students, so it cannot be attributed to economics education. This does not mean that economics students are more selfish in the real world. In the questions regarding hon-esty, selfish behavior directly damages someone else’s prop-erty rights. Even though subjects thought they would perform dishonestly, many of them hesitated to say so. Therefore, this may not be a result of economics students’ selfishness but a result of straightforwardly presenting their true thoughts. Fu-ture researchers should study whether Japanese economics students are actually more dishonest, and if so, why they do not hide this in a well-controlled experiment.

Recommendation for Further Research

The results of this study leave room for further investigation. First, the reason why Japanese students are different from those in the United States remains to be established. To clar-ify whether this is caused by cultural differences or labor market customs, it is necessary to conduct an experimental study in other Asian countries that have a similar cultural background and investigate the results by a study of the cus-toms in those labor markets. In addition, the investigation should be conducted in several other Japanese universities. In Japan, approximately 50% of 18-year-olds enter univer-sity. The level of intellectuality of university students varies, and so the results in a single university may not provide a fair representation of Japanese students.

Second, as described previously, it is an open question whether economics majors behave dishonestly in circum-stances in which they can obtain real money. Though a field experiment provide a counter example of selfish economics students, the difficulty of controlling a field experiment and the problem of property rights show that this question should be examined by a laboratory experiment to unify the condi-tion.

Third, it is important to understand why the decisions in the prisoner’s dilemma experiment and the answers to the public-goods problem questionnaires are inconsistent, even though they both have the same structure. To answer this question, it is necessary to clarify how the subjects feel when they make decisions in the experimental study, and when they choose answers in the questionnaire survey in which their rational decisions and answers are socially undesirable, and how that feeling affects their choice of decisions and answers.

REFERENCES

Carson, T. N., Saijo, T., & Yamato, T. (2002). Voluntary participation and spite in public goods provision experiments: An international comparison.

Experimental Economics,5, 133–153.

DOES ECONOMICS EDUCATION MAKE BAD CITIZENS? 239

Carter, J. R., & Irons, M. D. (1991). Are economists different, and if so, why?Journal of Economic Perspectives,5, 171–177.

Cox, S. R. (1998). Are business and economics students taught to be non-cooperative?Journal of Education for Business,74, 69–74.

Frank, R. H., Gilovich, T. D., & Regan, D. (1993). Does studying economics inhibit cooperation?Journal of Economic Perspectives,7, 159–171. Frank, R. H., Gilovich, T. D., & Regan, D. (1996). Do economists make bad

citizens?Journal of Economic Perspectives,10(1), 187–192.

Fischbacher, U. (2007). z-Tree: Zurich toolbox for ready-made economic experiments.Experimental Economics,10, 171–178.

Leung, K., & Tong, K. (2004) Justice across cultures; A three-stage model for intercultural negotiation. In M. J. Gelfand and J. M. Brett (Eds.),

The handbook of negotiation and culture(pp. 313–333). Palo Alto, CA: Stanford Business Books.

Marwell, G., & Ames, R. (1981). Economists free ride, does anyone else?

Journal of Public Economics,15, 295–310.

Seguino, S., Stevens, T., & Lutz, M. A. (1996). Gender and cooperative behavior: Economic man rides alone.Feminist Economics,2(1), 1–21. Yezer, A., Goldfarb, R. S., & Poppen, P. J. (1996). Does studying economics

discourage cooperation? Watch what we do, not what we say or how we play.Journal of Economic Perspectives,10(1), 177–186.

Zsolnai, L. (2003). Honesty versus cooperation: A reinterpretation of the moral behavior of economics students.American Journal of Economics and Sociology,62, 707–712.