Jour nal of Literature

and Ar t Studies

Volume 4, Number 2, February 2014 (Serial Number 27)

Publication Information:

Journal of Literature and Art Studies is published monthly in hard copy (ISSN 2159-5836) and online (ISSN 2159-5844) by David Publishing Company located at 240 Nagle Avenue #15C, New York, NY 10034, USA.

Aims and Scope:

Journal of Literature and Art Studies, a monthly professional academic journal, covers all sorts of researches on literature studies, art theory, appreciation of arts, culture and history of arts and other latest findings and achievements from experts and scholars all over the world.

Editorial Board Members:

Eric J. Abbey, Oakland Community College, USA Andrea Greenbaum, Barry University, USA Carolina Conte, Jacksonville University, USA

Maya Zalbidea Paniagua, Universidad La Salle, Madrid, Spain Mary Harden, Western Oregon University, USA

Lisa Socrates, University of London, United Kingdom Herman Jiesamfoek, City University of New York, USA Maria O’Connell, Texas Tech University, USA Soo Y. Kang, Chicago State University, USA Uju Clara Umo, University of Nigeria, Nigeria

Manuscripts and correspondence are invited for publication. You can submit your papers via Web Submission, or E-mail to [email protected], [email protected]. Submission guidelines and Web Submission system are available at http://www.davidpublishing.org, www.davidpublishing.com.

Copyright©2014 by David Publishing Company and individual contributors. All rights reserved. David Publishing Company holds the exclusive copyright of all the contents of this journal. In accordance with the international convention, no part of this journal may be reproduced or transmitted by any media or publishing organs (including various websites) without the written permission of the copyright holder. Otherwise, any conduct would be considered as the violation of the copyright. The contents of this journal are available for any citation, however, all the citations should be clearly indicated with the title of this journal, serial number and the name of the author.

Abstracted/Indexed in:

Database of EBSCO, Massachusetts, USA Chinese Database of CEPS, Airiti Inc. & OCLC

Jour na l of Lit e rat ure

a nd Ar t St udie s

Volume 4, Number 2, February 2014 (Serial Number 27)

Contents

Literature Studies

Trapped in the Quagmire of Misery: Exorcizing Neurosis of Violence in Mia Couto’s

Voices Made Night and Bessie Head’s Tales of Tenderness and Power 75

Niyi Akingbe

Causes of Pecola’s Tragedy in The Bluest Eye 85

WANG Xiao-yan, LIU Xi

Spatial Representations in Charles Dickens’s New York and London 90

Tzu Yu Allison Lin

Subversive Ambiguity in the Poetry of Delmira Agustini, Alfonsina Storni, and

Giovanna Pollarolo 98

Sara Villa

Inescapable Choices in Runaway 106

LIU Jun-min

Art Studies

Infamous Fame: Shaffer’s Tactic in Amadeus 111

Shu-Yu Yang

The Importance of Being on Screen: A Comparative Approach to Cinematographic

Versions of The Importance of Being Earnest by Oscar Wilde 118

Maria Isabel dos Santos Sampaio Vieira Barbudo

Special Research

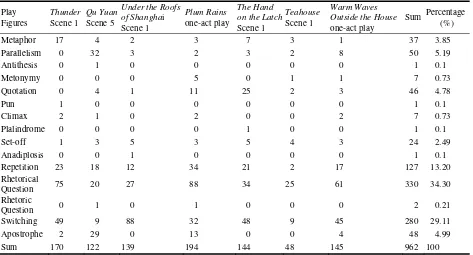

Utilization Frequency and Distributions of Drama Language Body Standard 123

WANG Jing-dan

Lêxis in Dionysius the Areopagite 129

José María Nieva

Modern Pedagogy and the Ratio Studiorum 137

Journal of Literature and Art Studies, ISSN 2159-5836 February 2014, Vol. 4, No. 2, 75-84

Trapped in the Quagmire of Misery: Exorcizing Neurosis of

Violence in Mia Couto’s

Voices Made Night

and Bessie Head’s

Tales of Tenderness and Power

Niyi Akingbe

Federal University Oye-Ekiti, Ekiti State, Nigeria

Arguably, Africa comparatively remains a huge repository of misery and violence in the 21st-century, an attempt to

account for narratives within the context of political development has posed an irresistible challenge and a

disturbing necessity for Mia Couto in Voices Made Night (1990)and Bessie Head in Tales of Tenderness and Power (1989). The position of Couto as a white Mozambican writer and Head as an exiled coloured South African writer, living in her adopted country of Botswana, provides them with privileged neutrality from which to view the

effect of the admixture of grinding poverty and violence as they ravage the landscapes of these countries. While

Couto does not fail to incorporate the significance of power struggle between FRELIMO (Front for the Liberation

of Mozambique) and RENAMO (Mozambique National Resistance) in the Voices Made Night, Head’s articulation of the complex manipulation of power becomes a resource for constructing a discourse of nationalism in Tales of Tenderness and Power. The paper intends to focus on the correlation between power and economic development in these anthologies. The paper will further examine how political power impacts on the socio-economic well being of

the local folks in the Couto’s Mozambique and Head’s South Africa.

Keywords: quagmire of misery, neurosis of violence, Mozambique, South Africa, poverty, Mia Couto, Bessie Head

Introduction

Mia Couto’s Voices Made Night (1990) and Bessie Head’s Tales of Tenderness and Power (1989) are

anthologies of short stories grounded in the relics of the Mozambican and South African past. Although, the power of the present to unearth the past strewn with misery and violence is problematized by the mismanagement of political power in post-colonial Mozambique and apartheid South Africa. It is a past mediated by the memory which tasks both Couto and Head’s imaginative conception of the dark periods in the Mozambican and South African histories. Faced with the indisputable recognition of the effect of mismanagement of power on the downtrodden masses of these two countries during these periods, Couto and Head are of the realisation that memory abhors the romanticism of amnesia in whatever disguise, most especially when it beckons on the re-telling in details of a political violence which threatened and almost destroyed their nations in the recent past. In this regard, Soyinka’s (1999) examination of the role of memory seems apt here “[t]he role of memory, of ancient precedents of current criminality, obviously governs our

Niyi Akingbe, Ph.D., associate professor of Comparative Literature, Department of English and Literary Studies, Federal University Oye-Ekiti.

DAVID PUBLISHING

TRAPPED IN THE QUAGMIRE OF MISERY

76

responses to the immediate and often more savage assaults on our humanity, and to the strategies for remedial action” (p. 20). Couto employs in his anthology of stories, the framework of memory which is deeply shaped by the surrealistic symbolic forms in navigating the RENAMO’s backlash against the FRELIMO’s political domination and policies which degenerated into the civil war and its effect on the rural folks in the postcolonial Mozambique. The history of postcolonial Mozambique is privileged as the discursive arena in the anthology for evaluating the relationship between economic development and political community. The deployment of memory and mythology for the narration of the Mozambican social and political history in Couto’s literary oeuvre has been explained in the words of Goncalves (2009):

Couto’s work draws heavily on the speech patterns of Mozambicans and on themes of traditional oral story telling. His narrative subjects and traditional myths join everyday life events of post war life in Mozambique. Couto blurs boundaries between the living and the dead, the individual and the community, and men and women. (p. 1)

If memory plays a significant role in the contextualisation of the Mozambican political tension and

violence in Voices Made Night,its significance is effusively appropriated as a narrative trope in engaging the

complex social relations among the black folks in the apartheid South Africa. In Tales of Tenderness and power,

Head dwells on the longstanding poverty exacerbated by racial tension between the black and white in the apartheid South Africa to articulate a poignant thematic preoccupation. Violence as the resultant effect of this tension is much felt in the black townships adjourning Johannesburg and Soweto which witnessed a concomitant increase in blood-letting during the apartheid. Commenting on what usually necessitate the justification for the perpetration of violence by a group against the other, Brennan (1993) posits that the narrativization of identity is grounded in spatial terms:

The need to separate subject from object, us from them—and in this case, to turn “them” into “objects”. In order to accomplish this, a “foundation fantasy” must be constructed in such a way as to reinforce the needs of the ego to comprehend itself as the “locus of active agency”. (p. 11)

More striking is Head’s unabashed depiction of violence in her Tales of Tenderness and Power, it is

demonised as the most debilitating factor militating against human development in the postcolonial Africa. By taken up the intersection of misery and violence in their anthologies, Couto and Head have utilised literature according to Edward (1990) Said, to articulate:

A crucial role in the establishment of a national cultural heritage, in the reinstatement of native idioms, in the re-imagining and re-figuring of local histories, geographies, communities. As such… literature not only mobilized active resistance to incursions from the outside, but also contributed massively as the shaper, creator, agent of illumination within the realm of the colonised. (pp. 1-2)

Head’s assessment of the balance of power between the races dramatizes the black township’s violence within the ambit of narrative fiction. But blending art and politics in her description of the uncanny circumstances generated by this social tension between the two races, Head constantly avoids a racial identification in these stories. Perhaps this distance is anchored on her racial status which is neither white nor black but coloured. Mosieleng (2004) contends that Head’s racial ambivalence is orchestrated by her fragmented personal background “which was fundamentally non-African in many respects, three of which may be singled out: language, companionship, and art” (p. 57).

TRAPPED IN THE QUAGMIRE OF MISERY

77

Africa. The import of history is particularly amplified in this paper by these writers whose commitment to the emergence of new geopolitical realities is directed toward the tasks of nation-building, emancipation and the enhancement of national consciousness. The socio-political consciousness of literature in African society is inevitable for several reasons: It is ingrained in the “traditional literatures” of the countries in the continent; Africa’s peculiar history has made the delineation of social issues crucial to the proper working of any profession or discipline; many writers espouse ideologies such as Marxism or socialism which make the advocacy of social change an article of faith; Africa’s contemporary predicament is such that arguably, no one with the sensitivity and insight of a “true” artist can be immune to engaging with it in his work. As Agovi (1995) claims, literature or artistic forms become the nerve centre of a network of complementary institutions which are “integrated into the state machinery by virtue of their pursuit of similar or related goals and ideals” (p. 10). Such institutions are made to pay allegiance to a common body of ideas and values that give rise to a sense of humanism in African society.

The paper is focused on these three planks: Firstly, it revolves around the crucial issues of society, literature, and memory. It suggests that there are certain identifiable interconnections between art, politics, and economic well-being of a particular state; Secondly, in focusing on the interconnection between economic and violence in the two anthologies over a particular period of time, the paper raises questions regarding how contending social forces arise as a result of socio-economic and political difficulties, and seeks to discover the precise nature of the literary depiction of social problems within the context of other forms of social intervention; Finally, the paper will conclusively aim at assessing the significance of literary insight in delineating social issues and the efficacy of the manner in which it proposes solutions to them in the anthologies.

Foregrounding the Intersection of Misery and Violence on New Historicism

Given its status as a critical mode which emphasises “the relationship between a text and the society” that produces it, the literary theory known as New Historicism has been chosen as the framework for this paper. It is a theory which interrogates the assumptions and attitudes governing how events are seen differently by the author and individual readers of a literary text. It relates a text to other texts produced at the same period in a given society; thus, literary and political connections can be drawn between the aesthetic elements embedded in the text, and the cultural realities that obtain in such a society (Tyson, 1999, p. 288). Within the ambit of New Historicism, the subject matter and thematic concerns of the texts under focus will be analysed with a view to drawing out these connections and discussing their significance within the analytical concerns of the paper. New Historicism is pre-occupied with the examination of literary texts from the perspective of their being embedded within the social and economic circumstances in which they are produced and consumed. For New Historicists, these circumstances are not stable in themselves and are susceptible to be re-written and transformed; from this perspective, literary texts are part of a larger circulation of social energies, both products of and influences on a particular culture or ideology.

TRAPPED IN THE QUAGMIRE OF MISERY

78

notions of the interface of language and text, but puts forward its own concept of the interconnection between culture and society. Like psychoanalysis, the theory explores the notion of power struggles and similarly advocates that power produces individual subjects. New Historicism shares with Marxism the notion that literature tells the story of the past. However, while Marxism advocates the complete liberation of the oppressed as a critical objective, New Historicism returns to the stories in the texts to find out how they affect society. These extensive borrowings from other theories have given it a flexibility that enables it to adapt the analytical tools and perspectives of other theories to suit its own purposes.

The overt concern of “New Historicism with power relations” among social classes in a given society makes it particularly appropriate to this study. Influenced by Michel Foucault, new historicist critics are interested in “concerns of power, authority and subversion at work in texts” (Carlson, 1993, p. 526). Selden (1989) also emphasises this pursuit when he states that “the New Historicists believe that Foucault’s work opens the way to new and non-truth oriented forms of historicist study of texts” (p. 161). New Historicism’s concept of history is diametrically at variance with those of the old historicists of earlier periods. For these predecessors, “History is a homogenous and stable pattern of facts and events which can be used as background to the literature of an era” (Abrams, 1981, p. 184). For the New Historicists, however, history is actually: A dynamic, unstable interplay among discourses, the meanings of which the historian can try to analyse, though the analysis will always be incomplete, accounting for only a part of the historical picture (Tyson, 1999, p. 287).

As is typical of New Historicism, Voices Made Night and Tales of Tenderness and Power’s

interpenetration of Mozambican and South African political histories is patently relative and involves a negotiation of meanings between competing groups rather than its imposition by a dominant group. In conformity with New Historicism, Couto and Head recognise in their anthologies that history is the history of the present, always in the making, and radically open to transformation and rewriting, rather than being monumental and closed. Just like New Historicists, the writers argue that any “knowledge” of the past is necessarily mediated by texts of different kinds. Hence, there can be no knowledge of the past without interpretation; the “facts” of history need to be read just like any other text. White (1978) suggests that knowledge of the past is determined by particular narrative configurations or stories as he states:

Histories ought never to be read as unambiguous signs of the events they report, but rather as symbolic structures, extended metaphors, that ‘liken’ events reported in them to some form with which we have already become familiar, in our literary culture… By the very constitution of a set of events in such a way as to make a comprehensive story out of them, the historian charges those events with the symbolic significance of a comprehensive plot structure. (pp. 91-92)

TRAPPED IN THE QUAGMIRE OF MISERY

79

barbarians, placing themselves in the former category, and everyone else in the latter category; monarchies propounded the divine right of kings as the natural order of things, rather than as an attempt to secure their power and influence; both Christians and Muslims demonise each other as “infidels” and other religions as “idol worship” in order to secure the loyalty of their own followers rather than because those other faiths are intrinsically evil; autocratic rulers throughout history have equated opposition to their rule with treason, regardless of whether such opposition is justifiable or not.

Suffice it to say that Couto and Head have argued in their anthologies that any “knowledge” of the past is necessarily mediated by texts, or to put it differently, that history is in many respects textual. A number of major consequences follow from this assertion. In the first place, there can be no knowledge of the past without interpretation. Just as history texts need to be read, so do the “facts” of history. From a new historical perspective, any reading of a literary text is a question of negotiation: a negotiation between text and reader within the context of history or histories that cannot be closed or finalised. Consequently, narratives in the

Voices Made Night and Tales of Tenderness and Power are to be understood in terms of negotiation rather than in the conventional sense of a pure act of untrammelled creation. For example, Perraudin (2005) comments on this negotiation between two opposing groups in a society and draws attention to what he perceives as the potential cause of political tension in the postcolonial African countries:

The acts of violence seem inevitably confined to a highly political and public sphere. The driving motivation behind these acts of torture, excorporations, and rape seems to stem from a desire to weaken the ability of the other to assert himself or herself within a realm of power that is in the process of being contested. (p. 73)

This implies negotiations which are a subtle, network of trades and trade-offs, and a jostling of competing representations. On this note, both Couto and Head have demonstrated in their anthologies, that work of art is the product of negotiation with a complex, communally-shared repertoire of conventions, and the institutions and practices of society.

Claiming the Burden of Exclusion

From a memory perspective, Mozambique is depicted as a politico-historical landscape in Voices Made

Night, whose first story begins with “The Fire”. Operating within a defined geo-political discourse which embraces an allegory of the mismanagement of the Mozambican postcolonial opportunities by its ruling elite, “The Fire” narrates a story of an aged couple living on the economic fringes of the rural Mozambique. At the critical phase of their lives in which they are now living alone and doing domestic chores by themselves, the old man became terribly apprehensive that the wife might die before him. To lessen this burden, the old man bought a spade and started digging the wife’s grave. The wife’s reaction to this bizarre act is a confounding bewilderment, which provides the reader an opportunity of viewing the adversarial relationship between the couple. However, the man became very sick and died due to the exhaustion he suffered from digging of the grave. He ironically ended being buried in the grave he dug for his wife.

TRAPPED IN THE QUAGMIRE OF MISERY

80

the Portuguese colonization for ten years, Mozambique attained independence in 1975. Nevertheless, FRELIMO’s tragic adventure into the political goose chase is inaugurated with a false start: It started ruling by proclaiming Mozambique a one-party state without conducting any elections. This FRELIMO’s Stalinist appropriation of power forced the RENAMO to take to a guerrilla warfare which lasted decades with colossal casualties in human and infrastructure.

Couto’s allegorical representation of the FRELIMO’s adoption of the Marxist-Leninst policies for the governance of Mozambique as exemplified in “The Fire” has been commented upon by Goncalves (2009):

The policies that FRELIMO has implemented in the country are a grave that is supposed to bury the old; but as in the Couto’s story if the old way does not die, then it has to be killed. The “digging” of these policies creates the need for the grave of the system itself. (p. 26)

The hypocrisy of the FRELIMO’s over subscription to the Marxist-Leninist propaganda is further Criticised by Couto (1990) in the dream of the old woman, where the falsehood of these policies is eloquently critiqued:

When the moon began to light up the trees in the wood, she leant back and fell asleep. She dreamed of times far away from there: her children were present, the dead ones and those still alive, the machamba was full of crops, her eyes slid over the green of it all. There was the old man in the middle, with his tie on, telling stories, lies for the most part. (pp.4-5)

FRELIMO is typified as the old man in “The Fire” and its adoption of the Marxist-Leninist propaganda in the shaping of the Mozambican national development policies is likened in the dream to a falsehood due to its ineffectiveness in moving the Mozambican economy forward.

A biting satire on the FRELIMO’s political philosophy is further drawn from mismanagement of the flood crisis in “The Tale of the Two Who Returned From the Dead”. It is a narrative which examines the plight of Luis Fernando and Anibal Mucavel who suddenly returned to the village, after they had been given up for dead following the devastating floods which swept away scores of people and submerged their village. The duo was denied food and relief materials which required the intervention of the FRELIMO regional authority to resolve. In reconstructing the Mozambican past within the context of New Historicism discourse, Couto (1990) essentially employs a deft allegorical gambit in examining the FRELIMO’s fetishization of Marxist ideological leanings as portrayed in the following passage:

The official arrived on the scene. He was a tubby man, his belly inquisitive, peeping out of his tunic…

“Look: they‘ve sent us supplies. Clothes, blankets, sheets of zinc, a lot of things. But you two weren’t included in the estimate”.

Anibal became agitated when he heard they had been excluded:

“What do you mean not included? Do you strike people off just like that?’ But you have died. I don’t even know how you came to be here”. “What do you mean died? Don’t you believe we are alive?” “Maybe, I’m not sure any more. But this business of being alive and not alive had best be discussed with the other comrades”. (pp.71-76)

The passage reveals FRELIMO’s bureaucratized approach to the treatment of national issues in the postcolonial Mozambique which leaves a lot to be desired, and has been polemically criticised in the words of

Goncalves (2009):

TRAPPED IN THE QUAGMIRE OF MISERY

81

an ideal, yet fabricated a country where the workers allowed FRELIMO to exercise its power in their name against the enemies of the people. The post-Independence project of FRELIMO took seriously the transition to socialism. The political elite of the country was influenced by European principles and failed to look within for the answers to the absolute question of what it means to be Mozambican. (p.35)

Correspondingly, placing emphasis upon the imbalance of power between the majority blacks and minority whites, recalls an inscription of political tension in the apartheid South Africa’s trajectory of violence

as Head’s Tales of Tenderness and Power exemplifies. This tension is grounded in “Oranges and Lemons”, a

story which anxiously expresses the effect of unmitigated violence perpetrated by the black gangsters, on the black folks during the apartheid South Africa. The dimension of crime, bloodshed, rape and maiming in these townships occur with frightening frequency. Head (1989) offers readers insightful penetration into lives of the residents who are cramped in the identical small match-box houses; mostly in and out of poorly-paid employment, and are generally: “helplessly trapped in one long dark nightmare without end”. The few who

“resisted the evil… were swiftly eliminated… ” (p.19). The helplessness of the black folks to ward off these

wanton killings, conveniently, made death very cheap in these townships. The story reflects a degeneration of humanity into bestiality caused by the political ills of apartheid.

We may without difficulty surmise that Head’s rendering of the narrative of “Oranges and Lemons” in a seamless intertextuality with references to poverty and the apartheid government’s unwillingness to criminalize gangsterism in the black townships, intends to indict the white minority-run South Africa apartheid regime. Power and its attendant problematic thus privilege the enabling discursive treatment of the glorification of violence by the subterranean rival gangs, whose profiles are trenchantly depicted in grotesque comic details of the narrative. It is a depiction which confirms Head’s familiarity with a blow-by-blow fluidity of crime occurrences in these run-down neighbourhoods. The objectification of pain borne by the victims of these black townships’ violence adequately provides a site for the reading of power articulation in the narrative. It is an

articulation Scarry (1985) has remarkably dealt with in her book, The Body in Pain:

The de-objectifying of the objects, the unmaking of the made, is a process externalizing the way in which the person’s pain causes his world to disintegrate; and, at the same time, the disintegration of the world is here […] made the direct cause of the pain. (p. 41)

We can conclude from this standpoint that Head’s characters in “Oranges and Lemons” in the likes of Old Ben, Jimmy Motsisi and Mary are victims whose bodies borne the weal of pain inflicted in the power-play manipulated by the rival gang leaders: “Hot Sparks” Phalane and “Big Brain Mazooki” alongside the witchy-bitchy Daphne Matsulaka whose paranoia get expressed in befuddled aspirations. Black on—black violence in the narrative invokes a power discourse which depicts residents of the black—ownships in “Oranges and Lemons” as casualties of a cul-de-sac racialized society. As such, they could only access the limited crumbs of social privileges available in the black townships, and could not rise above the apartheid colour limitations. By vocalizing the magnitude of this black township violence, Head has subtly mounted pressure on the apartheid regime to wake up to its legitimate responsibility of enacting social policies that will remarkably ameliorate this tiring macabre.

TRAPPED IN THE QUAGMIRE OF MISERY

82

the masses is dauntingly scandalized by Couto in “The Day Mabata-bata Exploded”. This is a fast-moving sombre narrative of the misfortune of an orphan, Azarias who constantly trudges a wooded valley set against the backdrop of a nameless village (in “The Day Mabata-bata Exploded”), from dawn to dusk tending the herd of cattle. However, one day while shepherding the herd, the prized-cattle otherwise called Mabata-bata stumbled upon a land mine which must have been planted by the RENAMO rebels and got blown into smithereens. In coming to terms with the understanding that his Uncle Raul would flog him for been careless, Azarias decided to hide himself in the valley as to stay away from home. But in heeding the call of his grandmother and Raul to come out of his hiding, he stepped on a mine which killed him instantly. The narrative heightens effect of the Mozambican war caused by the rivalry between FRELIMO and RENAMO which left in its wake army of maimed, pauperized and traumatized rural dwellers as its casualties. By evincing episodic narrative technique in “The Day Mabata-bata Exploded”, Couto is focusing attention on the plight of Azarias who became an orphan at a tender age and became a cowherd to his cruel uncle, Raul. This attention is further deepened by Couto’s evaluation of Azaria’s inability to access a formal education in the narrative due to poverty, which embeds a powerful metaphor for the interconnectedness of violence as harbinger of war and deprivation. For Couto, in effect, violence in “The Day Mabata-bata Exploded” problematizes the spate of political upheavals in the postcolonial Africa, whose narrations take pre-eminence over other national issues (Cazenave, 2005, p. 60). In explicating the symbolism of this story, Couto is at pain to stress that a society at war can never make any economic headway. Azaria typifies the collective Mozambican masses whose voices have been submerged in the bedlam of political schism, and whose lives have been disrupted by the ideological differences between FRELIMO and RENAMO which degenerated into civil war of 30 May 1977 to 4 October 1992.

It is interesting to note that the struggle for power occupies a prominent place in the African postcolonial discourses, but not limited to the Mozambican literary discourse. Oseghae (2004) while cautioning against inordinate struggle for power in postcolonial Africa posits that:

[I]ssues of contested identity, autonomy, citizenship, equity, power sharing and rights loomed larger than ever before

in postcolonial Africa (emphasis mine), thanks to the contradictions of globalisation, democratization, liberalization and other simultaneous economic and social processes that gave vent and legitimacy to non-state and anti-state claims and demands. (p. 10)

Inordinate struggle for power highlights a discourse which Head has also subjected to a critical evaluation in “A Power Struggle”: a story of bitter political rivalry between two royalties of the Tlabina clan, Davhana, and Baeli. The narrative focuses on the displacement of Davhana the throne’s heir apparent, by his younger brother Baeli, who crowned himself in his stead afterwards through sheer brigandage. Interestingly the narrative condemns inordinate ambition among politicians, in their blind pursuit of power in the postcolonial Africa. Although, the story revolves around a melange of narrative styles, from oral narrative and fictional narrative anchored on a political anecdote which has its setting in the pre-colonial South Africa.

TRAPPED IN THE QUAGMIRE OF MISERY

83

African continent commits against her kind are of a dimension and, unfortunately, of a nature that appears to constantly provoke memories of the historic wrongs inflicted on that continent by others” (p. 19). By exploring the way in which power is deviously pursued and aggressively hijacked by Baeli, Head ostensibly tends to demonstrate that power is often violently acquired in Africa through armed insurrection rather than by democratic means.

If the discourse of power and its acquisition process in the pre-colonial Africa foregrounds the thematic preoccupation of “A Power Struggle”, its deployment as a weapon for hounding the real and imagined enemies constitute its dialectic in “The General”. It is a narrative which anatomizes power and its intoxication in a nameless, postcolonial Southern African country, where a charismatic personality was elected on the basis of brilliance and patriotism. In retrospect, these twin attributes of the President have been elliptically alluded to by Head (1989) in the narrative “[T]hings were not so bad in the beginning. The President had charm and his intellectual brilliance was recognised throughout the whole world. He was completely objective and that was his charm” (p. 102). Characteristic of most leaders in the postcolonial African states, the nameless president in the narrative soon become a despot with egocentric and dictatorial credentials. His dictatorial proclivity manifests in the incarceration of scores of brilliant young politicians and intellectuals who were railroaded into jail and others forced into hasty exile. This madness continued unabated until a coup forced the president out of power. Inherent power dialogic embedded in “The General” has been appropriated by Head to highlight consequences of political tyranny and dictatorship in the postcolonial Africa.

Conclusions

The paper has articulated how memory has been appropriated to untangle a complex web of misery and

violence which permeated the narratives of Mia Couto’s Voices Made Night and Bessie Head’s Tales of

Tenderness and Power. Just as New Historicism does not consider art (images and narratives) as products to be merely contemplated for their aesthetic content, the paper has argued that stories in the anthologies fittingly operate as sites of “socio-political workshop” where political issues, economic anxieties, social struggles, problems, hopes and aspirations are addressed by the two writers.

The paper has subjected the literary interpretations of the political tension between FRELIMO/RENAMO in Mozambique and the black township’s violence in the apartheid South Africa within the historical epochs that produced the texts, which have invariably influenced the issues raised in them. Couto and Head’s reliance on memory in the anthologies becomes a means of negotiating the Mozambican and South African politics and societies in the paper. To this end, critical attention consequently shifts from the authors, the canons and the organic texts to the study of the forms and flows of power. In conclusion, memory facilitates in the texts, sites for the negotiation, authorisation, interrogation, and recuperation of the dialogic between the adversarial parties, between the ruler and the ruled.

References

Abrams, M. H. (1981). A glossary of literary terms. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Agovi, K. (1995). A king is not above insult: The politics of good governance in Nzema Avudwene festival songs. In F. Graham, & L. Gunner(Eds.), Power, marginality and African oral literature (pp. 47-61). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Booker, K. M. (1996). A practical introduction to literary theory and criticism. White Plains: Longman.

TRAPPED IN THE QUAGMIRE OF MISERY

84

Carlson, M. (1993). Theories of the theatre: A historical and cultural survey from the Greeks to the present (Expanded Ed.). Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Cazenave, O. (2005). Writing the child, youth, and violence into the Francophone novel from Sub-Saharan Africa: The impact of age and gender. Research in African Literatures, 36(2), 59-71.

Couto, M. (1990). Voices made night. England: Heinemann Education Limited.

Goncalves, L. (2009). Mia Couto and Mozambique: The renegotiation of the national narrative and identity in an African nation (Ph.D. Thesis, Carolina: University of North Carolina).

Head, B. (1989). Tales of tenderness and power. England: Heinemann Education Limited.

Mosieleng, P. (2004). Conditions of exile and the negation of commitment: A biographical study of Bessie Head. In I. Human (Ed.), Emerging perspectives on Bessie Head (pp. 105-125). Trenton, NJ and Asmara, Eritrea: Africa World Press, Inc.. Oseghae, E. E. (2004). Federalism and the management of diversity in Africa. Identity, Culture and Politics, 5(1-2), 164.

Perraudin, P. (2005). From a “large morsel of meat” to “passwords-in-flesh”: Resistance through representation of the tortured body in Labou Tansi’s La vie et demie. Research in African Literatures,36(2), 72-84.

Said, E. (1990). Figures, configurations, transfigurations. Race and Class, 32(1), 1-16.

Scarry, E. (1985). The body in pain: The making and unmaking of the world. New York: Oxford University Press. Selden, R. (1989). Practicing theory and reading literature:An introduction. New York: Harvester Wheatsheaf. Soyinka, W. (1999). The burden of memory, the muse of forgiveness. New York: Oxford University Press. Tyson, L. (1999). Critical theory today. New York: Garland Publishing, Inc..

Journal of Literature and Art Studies, ISSN 2159-5836 February 2014, Vol. 4, No. 2, 85-89

Causes

of

Pecola’s Tragedy in

The Bluest Eye

∗

WANG Xiao-yan

Changchun University, Changchun, China

LIU Xi

Changchun University, Changchun, China

Toni Morrison has a unique status in American literature. She is the winner of the National Book Critic Circle

Award, the Pulitzer for Fiction and many other literary awards. She was granted the Nobel Prize for literature in

1993, thus becoming the first African-American writer to receive this honor. Her first novel The Bluest Eye (1970) tells the story of the bitter and tragic experience suffered by Pecola, a little black girl, and loss of black people’s

self-respect, confidence, value, and culture. The present paper, first of all, gives a brief introduction of the story.

Then the paper explores the root causes of Pecola’s tragedy from two aspects: The cause of racial oppression and

self-hatred, and the cause of the loss in her independent consciousness. The paper concludes that Pecola is the

victim and scapegoat of racial oppression, self-hatred and the loss of her independent consciousness existing in

the black community.

Keywords:The Bluest Eye, causes, self-hatred, loss of independent consciousness

Introduction

Toni Morrison’s first novel The Bluest Eye (1970) tells the heartbreaking story of Pecola Breedlove, a

vulnerable black girl, living in Ohio, in the early 1940s. The 1993 Nobel Prize presentation speech points out,

“In her depictions of the world of the black people, in life as in legend, Toni Morrison has given the Afro-American people their history back, piece by piece”. Yet, at the same time her work is always symbolic of

the shared human condition, transcending lines of gender, race, and class. The most enduring impression her novel leave is of “empathy, of compassion with one’s fellow human beings” (YANG, 2004, p. 165).

The story centers around the tragic life of a little black girl named Pecola Breedlove. The Breedloves are the poorest family of the town, who live in a storefront of an abandoned store. Pecola, 11 years old, is black and

ugly. Her father, Cholly Breedlove, is driven to alcoholism by a life of appalling racial oppression. Once he burned up his house and turned his family outdoors. Driven by her husband’s rage and the unbearable misery of

her life, her mother, Pauline tries to escape from life and finds peace only working as a servant in white’s home.

She gives more care and attention to her master’s children than her own little girl. The poverty-stricken and frustrated couple is constantly quarreling and fighting. They totally ignore their daughter Pecola. At school

∗

Acknowledgements: This paper is part of the result of the research programs the authors have participated “The Study of

Counter-elite Essentiality in American Post-modernism Novels”, 2013, No. 265.

WANG Xiao-yan, associate professor, School of Foreign Languages, Changchun University. LIU Xi, lecturer, School of Foreign Languages, Changchun University.

DAVID PUBLISHING

CAUSES OF PECOLA’S TRAGEDY IN THE BLUEST EYE 86

other children bully and ridicule her, calling her ugly. Imprisoned by dire poverty and extreme misery, Pecola wishes for lighter skin, blond hair, and especially blue eyes like movie star Shirley Temple and other white girls,

which was the mainstream white cultural values at that time. She believes that her ugliness is the source of all her misery and that having blue eyes would be the key to happiness. Finally, through madness, she thinks that

her eyes have become blue. In her imagination she has been transformed into a pretty girl, as she is waiting for

love and happiness to come to her. Ironically, her drunken father gets home, and gives “love” to his daughter by raping her. The little girl becomes pregnant and she gives birth to a stillborn child. She sinks deeper into

despair and madness. In the end of the novel, “She was so sad to see. Grown people looked away; children, those who were not frightened by her, laughed outright… the damage done was total” (Morrison, 1970, p. 122).

Pecola’s father died in the workhouse; her mother still does housework. Pecola and her mother move to a little house on the edge of the town. The black little girl is often seen picking her way “between the tire rims and the

sunflowers, among all the waste and beauty of the world-which is what she herself was” (Morrison, 1970, p. 122).

The Causes of Pecola’s Tragedy

The Cause of Racial Oppression and Self-hatred

The Bluest Eye depicts the pernicious psychological impact that the dominant white cultural values have

had on black people. Published in 1970, The Bluest Eye has its setting in the black community in Lorain, Ohio,

in 1941, long before the Civil Rights Movement. In those days, blackness was synonymous with ugliness. The

dominant white culture exercised its hegemony and dictated standards of beauty. Many black people accepted

an internalized white values and developed self-contempt and self-hatred for themselves or other black people,

making some of their own people victims and scapegoats.

In Hate Prejudice and Racism (1993), Milton Kleg points out: “Self-hatred refers to the condition where

an individual attempts to blame his or her group for those problems encountered by acts of prejudice” (as cited

in YANG, 2004, p. 183). Self-hatred is a result of thorough assimilation into the dominant white culture and

ideology and complete denial of one’s own racial roots and cultural heritage. Self-hatred is an important theme

of The Bluest Eye. By exploring self-hatred among the black people, The Bluest Eye reveals the deep

psychological injury white racism has inflicted on African-Americans.

Even the mixed blood girl victimized the black people. In one of the most vivid scenes in the novel, Toni

Morrison describes a particular type of blacks—brown-skinned people. These brown girls have lighter skins

than other black people because their mixed blood. Many of them are descendents of former slaves who were

house servants. Working in the house rather than in the fields, they were closer to their slave owners than the

field Negroes. It was a common thing for a white master to have babies with black maids.

They hold themselves up high above the other blacks. These sugar-brown girls are from better-off families,

“go to land-grant colleges, learn how to do the white man’s work with refinement” (YANG, 2003, p. 122),

marry successfully, living in their own inviolable worlds in quiet, black neighborhoods. With a certain

proportion of white blood, they feel superior to other black people. Like the whites, they detest blackness, and

project their hatred and contempt for it onto Negroes with darker skins. They blindly believe in the mainstream

CAUSES OF PECOLA’S TRAGEDY IN THE BLUEST EYE 87

surgery that makes the nose narrow and higher, or straighten their hair and may be dyed it blond. They were

more alienated from their black cultural heritage.

Pecola was growing under such circumstances everyday she prays for a miracle to happen, so that she is given a pair of the bluest eyes. She is convinced that if she had blue eyes, she would become pretty and happy

and that all her problems would be gone. Yet the hard reality cheated her. She not only could not get the love

from her parents, but also bullied by other children. At school, Pecola kept her head down, showing she was very timid and frightened. She was very lonely, too. At recess kids played together, but nobody ever played

with her. She was “ugly” because she is very black, she represented an image of extreme ugliness and dire poverty. All the kids, including Pecola herself, thought so because all of them were educated to internalize the

value that dictates standards of beauty. Even the brown-skinned lady—Geraldine who even called black children “niggers”. Because of her distorted motherhood, her son—Junior also bullied Pecola.

Pecola is a victim of racial oppression and a scapegoat for the self-oppression and self-hatred existing in the black community.

The Cause of the Loss in Her Independent Consciousness

In The Bluest Eye, Pecola, who is described as “the popeyed, tongue-tied kid” (Baldwin, 1984, p. 14) in

America with racial discrimination, could not accept her own independent subject identity and accept the image others imposed on her. Furthermore exposed to the influence of the family, community, mass media, school and

others, she has lost the black aesthetic value. Her desire for the blue eyes indicates the loss of her independent consciousness.

Pecola lives in a family without love, safety, and warmth. Cholly is an irresponsible father who never shows paternal love to her and Pauline, her mother, who has self-hatred, who excludes the black culture, passes the

sense of ugliness and inferiority to her, which impels Pecola to accept the white aesthetic values and concept unconsciously. The dislike and rejection of her mother to her have intensified her self-denied and her loss of the

subjective consciousness, “which means that human beings as subject in a real world realizes consciously that

they take the special, superior and dominate position” (Kriegel, 2009, p. 67). The subjective consciousness

makes her feel fearful to the development and even fall into the crisis of the self-recognition. Lacking the parental love and guidance, Pecola has illusion of getting the blue eyes to escape from the miserable life.

Morrison (1970) writes:

It had occurred to Pecola some time ago that if her eyes, those eyes that held the pictures, and knew the sights-if those eyes of hers were different, that is to say, beautiful, she herself would be different. If she looked different, beautiful, maybe Cholly would be different, and Mrs. Breedlove too. Maybe they’d say, “Why, look at pretty-eyed Pecola. We mustn’t do bad things in front of those pretty eyes”. (p. 40)

If she had the blue eyes, parents would stop fighting and her brother would not run away and her teachers

and classmates would like her and would gaze at her. Having blue eyes means having everything—love,

acceptance, family, and friend for. Obviously, Pecola has already accepted the white beauty norms and prays to get them everyday.

CAUSES OF PECOLA’S TRAGEDY IN THE BLUEST EYE 88

marginalized, so the black loses their subjective consciousness, which makes them lose their own culture and aesthetic value. In that case, the blacks have unhealthy mentality and find their beauty from Pecola’s ugliness. So

she has experienced indifference of her family and discrimination from the others; as a little girl how could she observe the world with the correct angle?

In order to change her life, Pecola first thinks that she should change the things she has seen and she believes

that changing the color of her eyes would change her fate, because from her point of view, people with blue eyes would see the beautiful world. The desire of the blue eyes indicates that she has internalized the white norm of the

beauty. Therefore, she has lost the independent consciousness to think and has forgotten that she is an independent human being. In our opinion, when she faced the unfair treatment, she should have resist rather than

escape and when others regarded her as ugliness, she should have reject the model of socialization they represented. The fact is, under that circumstances, that she could only accept and endure. Instead of venting her

anger, she would rather live with a dream of having blue eyes. She is made by the circumstance to lose her independent consciousness and lives in the dream which makes her sink deeper and deeper into the abyss of misery.

Her dream of finding shelter in her fantasy of whiteness mercilessly destroyed, the girl is thrown into madness.

Conclusions

Pecola is a fragile and delicate child when the novel begins, but at the end of the novel, she has been almost

completely destroyed by the racial oppression, self-hatred, and her loss of independent consciousness.

Pecola is a symbol of the black community’s self-hatred and belief in its own ugliness. Others in the

community, including her mother, father, and Geraldine, act out their own self-hatred by expressing hatred

toward her. Therefore, in The Bluest Eye, they considered white color, blonde hair, and the bluest eye as the

standard of beauty, and the black skin as the symbol of dirty and ugliness. They lost and abandoned themselves, changed the value standard and denied the fact of existence as the black, which became the source of their tragedy.

At the end of the novel, we are told that Pecola has been a scapegoat for the entire community. Her ugliness

has made them feel beautiful, her suffering has made them feel comparatively lucky, and her silence has given them the opportunity for speaking. But because she continues to live after she has lost her mind, Pecola’s aimless

wandering at the edge of town haunts the community, reminding them of the ugliness and hatred that they have tried to repress. She becomes a reminder of human cruelty and an emblem of human suffering.

Pecola’s fate is a fate worse than death because she is not allowed any release from her world—she simply moves to “the edge of town, where you can see her even now” (Morrison, 1970, p. 122). The paper believes that

the loss of black people’s independent and subjective consciousness leads to the loss of their black culture. In order to get the real independence, the blacks must recover their subjective consciousness, regain self-respect,

and self-confidence, and realize that they play a crucial role in the survival of their nation.

References

Baldwin, J. (1984). Notes of a native son. Boston: Beacon Press.

Carl, D. M. (2000). Texts, Primers, and Voices in Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye Critique. Critique, 41(3), 251-260. CHANG, Y. X. (2002). A survey of American literature. Tianjin: Nankai University Press.

Dittmar, L. (1990). The politics of form in The Bluest Eye. A Forum on Fiction, 23(2), 137-155.

CAUSES OF PECOLA’S TRAGEDY IN THE BLUEST EYE 89

James, W. (1997). Morrison’s the bluest eye. The Explicator, 55(3), 172-175.

Kleg, M. (1993). The prejudice and racism. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Kriegel, U. (2009). Subjective consciousness: A self-representational theory.Oxford:Oxford University Press.

Kuena, J. (1993). The Bluest Eye: Notes on history, community, and black female subjectivity. African American Review, 27(3), 421-431.

Morrison, T. (1970). The bluest eye. New York: Washington Square Press.

Rubinstein, A. T. (1988). American literature: Root and flower.Beijing: Foreign Languages Teaching and Research Press. Wong, S. (1990). Transgression as poesis in The Bluest Eye. Callaloo, 13(3), 471-481.

YANG, L. M. (2003). Contemporary college English. Beijing: Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press.

Journal of Literature and Art Studies, ISSN 2159-5836 February 2014, Vol. 4, No. 2, 90-97

Spatial Representations in Charles Dickens’s

New York and London

Tzu Yu Allison Lin

Gaziantep University, Gaziantep,Turkey

The purpose of this research is to see the image of New York and London in Charles Dickens’s writings. In

American Notes (1987), on the surface, the city shows Dickens’s eye of observation, revealing the dark side of the city. However, his writing expresses more than what he sees. In this paper, the author sees New York and London

not only as realistic accounts of what things look like, but alsoa true realization of how Dickens feels about himself,

and about the country in which he was situated in. In Oliver Twist (2003), a New York prison can be linked to Dickens’s London, representing the darkness of the city with the prison cell and its suggestiveness, including

punishment, exclusion, and dehumanization. A New York Asylum reveals the dialectic of order and disorder, in a

way which alienation brings out the crisis of humanity. This research shows that New York is an extension of

London, in a way which the personal crisis is vividly revealed, as the reader can see in Charles Dickens: A Life

(2012). Through New York, Dickens is more conscious about his London childhood, as spatial representations of

London have their own symbolic meanings.

Keywords: Charles Dickens, New York, London, space, representation, prison, insanity

Introduction

In this paper, the author deals with an issue, which is essential to the study of Charles Dickens’s writings. Critics usually focus on the image of the city of London, in a way which they found Dickens and his novels were

best known. And yet, the author argues that Dickens’s American Notes (1987) also plays a critical role in

Dickens’s writing career. It takes a form of travel writing, but it does not only show an ordinary tourist’s point of

view. Dickens’s New York, in his writing, expresses a particular perspective of how this Victorian writer sees himself and his own past as an internationally celebrated writer. His New York is significant, because through

that city, the reader can see the way in which Dickens comes to connect to his childhood memory in London through writing.

America

The image of America seems to be a fairy land for the British travelers. Daniel Defoe’s most famous

character, Robinson Crusoe, has travelled to “an un-inhibited island on the Coast of America” (Defoe, 1998, title

page), as in his title page of the novel Robinson Crusoe shows. Although Crusoe’s trip was not to the continent

Tzu Yu Allison Lin, Ph.D., assistant professor, Department of Foreign Language Education, Gaziantep University.

DAVID PUBLISHING

SPATIAL REPRESENTATIONS IN CHARLES DICKENS’S NEW YORK AND LONDON 91

itself, the spirit is to travel and to see a different kind of world, such as Charles Dickens himself, as a Victorian

traveler, would do. Dickens’s American Notes may not be as well-known as his other fictional writings about the

city of London. According to Grubb’s American Notes (1950),“appeared in London on October 18, 1842” (p. 101).

In general, the reviewers do not like it. One of the “unfavorable reviews” even says that this work of Dickens’s

“has no real literary value” (Grubb, 1950, p. 101).

Dickens may be able to use his travel experience later in his novels, as Meckier (1984) points out, to

“[transform] an unsatisfactory England into that best of all possible worlds he had hoped to discover in

America” (p. 273). Stone (1957) also claims that Dickens’s travel experience in America, is certainly not

purposeless and useless. Dickens’s American Notes can be read as a way, in which one can see “his artistic

methods and limitations” (p. 464). To be more precise, as Heilman (1947) puts it, the American experience is

Dickens’s “source of materials to be used in satirizing Europe” (p. 21), in his later writings. At the first glance, in

general, American Notes shows that Dickens “became disenchanted with many things American” (Waller, 1960,

p. 535). There may be rumors about why Dickens “became soured upon American manners” and “customs” (Grubb,

1951, p. 87). And yet, the author would argue that his image of New York is certainly worth a discussion in depth.

New York and Dickens’s Dual Vision

Dickens’s perspective of the city of New York indicates a double ways of seeing—First of all, he sees

people and things as what an outsider or a traveler can possibly see; and second, he sees the city as a

representation of a part of his personal history. More precisely, this personal history refers to his memory as a

young man. This dual way of seeing a city represents his own thoughts and feelings, as Dickens’s narrative forms

a threshold between his own self and the narrator in the travel writing. Spaces of New York City are filled with

metaphorical meanings. But the question is, why are these images significant?

The image of Charles Dickens’s New York City is a “witch’s cauldron”, which is “hot”, “suffocating”, and

“vaporous” (Dickens, 1987,p. 142). Just as Poe (1996) points out in his short story, “The Man of the Crowd”

(1840), there are certain books which are not suppose to be read, “[t]here are some secrets which do not permit

themselves to be told” (p. 388). Here, the author would like to add up one more thing—the city of New York, in

Dickens’s narrative, is a city which does not permit itself to be visited.

Poe’s man of the crowd is an observer. This man seems to be indicating Charles Baudelaire’s image of the

flâneur, which is a representative figure, finding himself “[t]o be away from home and yet to feel oneself everywhere at home; to see the world, to be at the centre of the world, and yet to remain hidden from the world”

(Baudelaire, 1995, p. 9). As a traveler, Dickens has his own friends who are able to take him around the city, so

that he can feel free to see whatever he wants to see. Although he does not tell his readers whos these “friends”1

are, we can be sure that he is “grateful” to have their company, without even mentioning about any of their names,

as he writes in the 1859 Library Edition Preface. These friends make Dickens’s observation of New York City

possible, as he travels and becomes a man of leisure, when he visits places such as Music and Dance Halls for

1 According to Tomalin (2012), Washington Irving was one of the friends, who “spoke in his praise” in “the New York Dickens

SPATIAL REPRESENTATIONS IN CHARLES DICKENS’S NEW YORK AND LONDON

92

entertainments. He is also engaged in seeing places he wants to see, particularly Institutions such as prisons and

mental hospitals.

The streets of New York City have their own textual and social meanings. Broadway is the first street, which Dickens addresses, when he stays in “the upper floor” of “the Carlton House Hotel” (Dickens, 1987, p. 128).

Dickens could gaze at the stream of life on the street from his window. This stream of life shows Broadway as “a

sunny street”. Dickens’s hotel room window is burning because of the heat of the sun, through which, in “ten minutes” time, he sees all kinds of well-dressed ladies, and their colorful parasols. Black and white coachmen are

in different colors and styles of hats:

In straw hats, black hats, white hats, glazed caps, fur caps, in coats of drab, black, brown, green, blue, nankeen, striped jean and linen; and there, in that one instance (look while it passes, or it will be too late), in suits of livery. (Dickens, 1987, p.128)

In Dickens’s writing, one can see that he seems to be taking a picture through his hotel room window as a

traveler can do, as his eye becomes a symbolic camera eye, looking at people’s movements and their fashion styles as they pass. As a traveler, his mood is cheerful, since Broadway is so sunny, as:

[T]he pavement stones are polished with the tread of feet until they shine again; the red bricks of the houses might be yet in the dry, hot kilns; and the roofs of those omnibuses look as though, if water were poured on them, they would hiss and smoke, and smell like half-quenched fires. (Dickens, 1987, p.128)

The heat of Broadway feels just like Dickens’s passion of looking at the crowd, as the adventure of walking

around New York City has just begun.

And yet, the bright vision and the cheerful mood of Dickens’s, after a while, turn to an image of horror,

when he walks along Bow Street. This street represents an area, which is full of “narrow ways, diverging to the

right and left, and reeking everywhere with dirt and filth” (Dickens, 1987, p.136). This is one of the worst places

in Dickens’ New York, because it is very dirty and filthy. For instances, the houses here are “prematurely old. See

how the rotten beams are tumbling down, and how the patched and broken windows seem to scowl dimly, like

eyes that have been hurt in drunken frays” (Dickens, 1987, p.136).

Houses seem to indicate the condition of people who live there. Apparently, people live in Bow Street are not very healthy, and they look old and shabby. The windows of their houses are “broken”, as if those people are

as drunk as “pigs” (Dickens, 1987, p.136). Their eyes have been injured because they are unconscious and drunk.

Dickens’s hotel room window in Broadway seems to be perfect. To compare to other people who live in different

areas of New York, people in Bow Street cannot even be named in human terms—even the place they live is like a “wolfish den” (Dickens, 1987, p. 137). There is this “Negro” (Dickens, 1987, p. 137) lives in this “miserable

room”, among one of the “squalid street” and a “square of leprous houses” (Dickens, 1987, p. 137). In Broadway, there are black men and white men. At least they all look like human beings. But here, black man is a nameless

“Negro”, with a socially insignificant fever in his head. In the bottom of the social class, this person does not even bother to “look up”, when the officer asks him for what happened to him (Dickens, 1987, p. 137).

Dickens’s term “Negro” here suggests the man’s being black. It has a stronger implication of Dickens’s discontent of “[t]he barbarity of the slavery system” (Pound, 1947, p. 124), as he sees “the horrors of the

SPATIAL REPRESENTATIONS IN CHARLES DICKENS’S NEW YORK AND LONDON 93

The term “Negro” is particularly meaningful, when in the context of Southern America, as people can “own, breed, use, buy and sell” their slaves (Adrian, 1952, p. 319). As Claybaugh (2006) points out, “British antislavery

activities offered their American counterparts moral example, financial support and practical advice. This support peaked in the early 1840s, at the moment when Dickens made his tour of the United States” (p. 444). Here the

author’s point is, the general impression of America, in Dickens’s writing, seems to be rough and barbaric.

Clearly, the general condition of the way in which people live is not as good as Dickens has expected—to a least expectation of a human being’s living condition. Although it is not particular necessary to see Dickens’s

American Notes as a “propaganda for reform” (Goldberg, 1972, p. 74), still, the author can see more about the human conditions in America that Dickens has noticed. For Dickens, in some areas of New York,

people—including white or black, men or women, their way of living makes them all look like animals, as he noticed, “Such is life: all flesh is pork!” (Dickens, 1987, p. 134). In some certain extreme social conditions, the

way people live represents them as only different kinds of “pigs” (Dickens, 1987, p. 134), or “a pig’s likeness” (Dickens, 1987, p. 134).

These people’s situation seems to be indicating Dickens’s moment of Dickens’s own awakening, especially, when he sees the “colour prints of Washington, and Queen Victoria of England, and the American Eagle” on the

wall of these “pigeon-holes” houses (Dickens, 1987, p. 136). It is hard to tell, from Dickens’s writing, how people in New York feel about Queen Victoria. And yet, the contrast between monarchy and “an American form

of Government, with an elective head of State” (Benson & Esher, 1907, p. 640), is still there. According to the King of the Belgians, in his letter written in Laeken, on 15th December 1843, to his niece Queen Victoria, the

reader can see that some people in England, “for some years”, thought “that Royalty was useless and ignorant” (Benson & Esher, 1907, p. 639). The color prints of Queen Victoria of England on the wall in the street of New

York, certainly brings out “a very aristocratic feeling” (Benson & Esher, 1907, p. 640).

It seems that both worlds, across the Atlantic, are each other’s counterparts. The King of the Belgians

remembered that there was “a very rich and influential American from New York”, he thought that the Americans need “a Government which was able to grant protection to property, and that feeling of many was for Monarchy

instead of the misrule of mobs” (Benson & Esher, 1907, p. 640). In Dickens’s New York, ironically enough,

images such as “designed ships, and forts, and flags, and American Eagles out of number” can particularly be seen in those poor areas, in a way which the rich American man from New York in the letter of the King of

Belgians, seems to have a point. These colorful images of American dreams come to make a sharp contrast with the reality of the visible world of New York City—the area of “ruined houses, opened to the street, whence,

through wide gaps in the walls” (Dickens, 1987, p. 138). The “wide gaps” of the walls seem to ironically indicate the “gaps” between the dream image and the visible reality, reinforcing the ambiguity of the private and the

public spheres, as the houses are opened to the street.

The Victorian Prison and Insanity

Dickens has made a decision of leaving America and going back to England, when he was in New York.

Most probably, he realizes that home is not perfect, but it seems to be at least livable. This City of New York, in his eyes, is nothing more than a broken dream. Visiting a Lunatic Asylum in Long Island area, Dickens was again,

SPATIAL REPRESENTATIONS IN CHARLES DICKENS’S NEW YORK AND LONDON

94

called the “moping idiot”, with “long disheveled hair”, “the gibbering maniac”, “hideous laugh and pointed finger” (Dickens, 1987, p. 140). The wall of the dining-room is “empty”, “with nothing for the rest of the eye to

rest”. Among these “bare, dull” and “dreary” spaces, the author would argue that Dickens sees a sadness of this “refuge of afflicted and degraded humanity” (Dickens, 1987, pp. 140-141). The true meaning of American spirit,

here in Dickens’s eyes, is something as hot and as dry as a desert, “sickening and blighting everything of

wholesome life with its reach” (Dickens, 1987, p. 141). New York seems to be the most of it, with the “crowd” of terror in the “madhouse”. The threshold of the mental hospital reveals Dickens’s feeling of “deep disgust and

measureless contempt” (Dickens, 1987, p. 141). It is a threshold of non-returning, no matter physically or spiritually. Dickens does not even look back again.

Home is not perfect, but as least it has a sense of humanity. Dickens’s observation of prisons in New York, once more, makes readers see the vivid image of a kind of human-as-animal way of living. Even prisons back

home in England, for Dickens, treats the prisoners as human beings, instead of caged chickens. For example, Dickens sees this man of 60 years old, who “has murdered his wife, and will probably be hanged” (Dickens, 1987,

p. 132). Dickens depicts this man in his “small bare” prison cell, in a way which shows that this man is like an actor on the stage, with a spot light coming from above, as “the light enters through a high chink in the wall”

(Dickens, 1987, p. 132). The wall of this prison cell indicates the consciousness of the man and his thought, when he is reading in this “four walled room” (Benjamin, 1973, p. 37). And yet, ironically, this man is not allowed to

walk freely in the city, unlike the flâneur. He looks up at Dickens’s eyes, “for a moment”, but soon he “gives an

impatient dogged shake; and fixes his eyes upon his book again” (Dickens, 1987, p. 132).

Dickens (1987) tells the officer, that “[i]n England, if a man be under sentence of death, even, he has air and exercise at certain periods of the day” (p. 132). Dickens (1987) also notices that there is a “lonely child, of ten or

twelve years old” also in another prison cell. He is again in deep shock, when he realizes that this boy is the son of that reading man. The function of this boy is to be “a witness against his father” (p. 132), but he is also treated as

a prisoner, staying in a separate cell for a month.

The child “of ten or twelve” in the city prison of New York, most probably makes Dickens thought about his

own childhood. It was almost twenty years ago before he visited America. According to Angus Calder, in the year

of 1823, Dickens’s “family moved to London, faced with financial disaster”, because Dickens’s father John Dickens “had been arrested for debt, and soon the whole family, except for Charles who was found lodgings,

joined him in the Marshalsea Debtors’ Prison” (Calder, 1987, p. 7). Although Dickens did not join the family in the prison, and yet, according to Calder, this “family shame” “transformed him”, “which haunted him till his

death” (Calder, 1987, p. 7). The shameful feeling is like the shadow under the long and thick “brick structure” of “the Marshalea’s wall” (Tagholm, 2001, p. 172). This boy in the city prison of New York happens to have a

similar age with Dickens’s, when his family was in prison. Dickens had the feeling of humiliation not only because of his father’s being in prison, as “the buildings were old and shabby” (Tomalin, 2012, p. 23), but also

before that had happened in February 1824, the family was “pursued by creditors with increasing ferocity, their furious knockings and shoutings at the front door driving his father to ignominious hiding places upstairs”

(Tomalin, 2012, p. 22). Dickens, “as the man of the family, just twelve years old”, had absolutely “[n]o help” from any other family members—not even from his uncle William Dickens who owned a coffee shop in Oxford Street.