SUPERVISED BY: PROF SOLVAY GERKE

THESIS:

SOCIOGENESIS OF TATTOOS IN BRUNEI DARUSSALAM

Acknowledgements 3

Abstract 4

Acknowledgements

Firstly I would like to thank my research assistants Fizzah Fendi, Bashirah Maidin and Aqilah Boestamam for accompanying me to head to designated locations and giving me ideas and inspiration. I would also like to thank Professor Solvay Gerke for letting me have this eye opening topic and guiding me on what is relevant, I would not have any form of drive because I felt like writing everything. And last but not least I would like to dedicate this towards my participants who have been giving me materials and shedding the best light and explanation to contribute towards my thesis.

Thank you my fiancé, Faizul Morni for tolerating me during the stressful times of Final Year and still wanting to marry me - and my family for always giving me brain fuel for those many sleepless nights.

I dedicate this to my father, Col Haji Zainal Ariffin bin DP Haji Ahmad, for always being my inspiration in every aspect of life and always being the rock to my windy days.

“There is no known culture which people do not paint, pierce, tattoo,

reshape or simply adorn their bodies”

- Gay and Whittington (2002)

Tattoos have existed in diverse array of cultures - proven archeologically, and have experience some form of change. In this thesis I will use a concept explained by Graaf and Maier (1994)1 in their Sociogenesis Reexamined which is the idea of sociogenesis - the evolution of societies or a particular society, community or a social unit2 due to interpersonal experiences – in the view of George Herbert Mead’s interpretation of Charles Darwin3 - the development of humans and the changing of the society during the evolution. This thesis is to uncover the sociogenesis – the progression in perception, methods, and culture of tattoos in Brunei. And also to distinguish the difference between the situation of tattoos somewhere around 50 years ago and now. Some of the notable things that have caused the changes in Brunei Darussalam are religion, globalization, media and education where each topic will be discussed intensively. The main research question for this would be, to explain the sociogenesis of tattooing in Brunei. The data collection for this essay is gathered through 12 open-ended interviews with several participants who have tattoos and also those who are well versed in the history and art of it. Results of this study will show the sociogenesis of tattoo - the changes of perception, art, purpose, methods, and ideology throughout time, in Brunei.

CHAPTER : 1

1 Graaf and Maier (1994), Sociogenesis Reexamined, Springer Science and Business Media. P.1.

1.1. Introduction

Tattoos have been relevant through out ancient times with evidence of an “Ice Man” called Ötzi4, preserved by ice, aging back to eras before the Egyptian mummies, which backdates to 5,300 years where as the mummies are 4,000 years. The existence of tattoos as Levy theorized in her writing ‘Tattoos in Modern Society’ (2008) explained that reasons for tattoos have been suggested to include – adornment, indication of status, magical powers, amulets or health care (acupuncture)5. The word “tattoo” is originally ‘tataw’ or ‘tatau’ or ‘tattaw’ derived from the Polynesian word – “ta” a Polynesian word referring to striking (Scutt & Gotch, 2007)6.

Figure 1: Timeline of tattoos7 1.2. The Sociogenesis of Tattoos in Brunei

4 Levy (2008), Tattoos in Modern Society, The Rosen Publishing Group. P. 9. 5 Ibid.

6 Scutt, R.W.B., & Gotch, C. (2003). Early European encounters with Polynesian tattoos. In J.D. Lloyd (Ed.), Body Piercing and Tattoos (pp. 33-44). Farmington Hills: Greenhaven Press.

Sociogenesis is a term coined by Norbert Elias, German sociologist in his The Civilizing Process8, which is the civilizing process over time repeated in the psychogenesis of an individual’s life – however in this thesis I will use

sociogenesis in the form of society rather than an individual – by measuring the progression using individuals who are around their youths and those who are a generation older. Blunden (2012) explains, which is closer to my scope of research – ‘the unfolding of a multitude of real social situations in any community, as opposed to broad social formations’9

An overview of the sociegenesis of tattoos in Brunei is that tattoos were used as a ‘rite of passage’ symbol and slowly progressing into a form of individuality and fashion statement.

1.3. Background

8 Elias (2000), The Civilizing Process, Wiley.

During my visit to the Musee du Quai Branly, the array of showcase from each country was detailed – and I was determined to see the insert on Brunei. However, that section was concluded under

Borneo. Which triggered me to make this thesis – to prove that Brunei does have its own brand of tattoo. In explaining the section

of olden cultural practices of tattoos in Brunei –

I have dug way back to histories around the 17th century, where missionaries would have some details on tattoo practices in Brunei. In

this section I will try to elucidate pthe origins and background of Brunei in relation to tattooing activities.

So starting off by the 16th century, Brunei was a well-organized and prosperous Malay-Islamic Sultanate, ruling almost all Northern Borneo, which became one of the main ports of calls during the era10. Then in the 19th century James Brooke interfered with the Malay world politics, and extracted gifts from the royals to a point where he virtually extorted enormous tracts of land along the northwestern coasts of Borneo, which constitutes two-third of the Bruneian states11. Even though the past loss, practices in tribes around Borneo in remote and in central areas still maintained where tattooing is one of them12, and is

10 Tajuddin (2012), Malaysia in the World Economy (1824-2011): Capitalism, Ethnic Divisions and ‘Managed’ Democracy, Lexington Books : Pennsylvania. P.35. 11 Ibid.

12 Keppel (2014), The Expedition to Borneo of H.M.S. Dido for the Suppression of Piracy, Bookpubber.

usually done by people of the remote areas or ‘orang Ulu13’. Sir Henry Keppel

(2014) mentioned of the types of orang Ulu that practices tattooing in his The Expedition to Borneo of H.M.S. Dido for the Suppression of Piracy14 and notes down

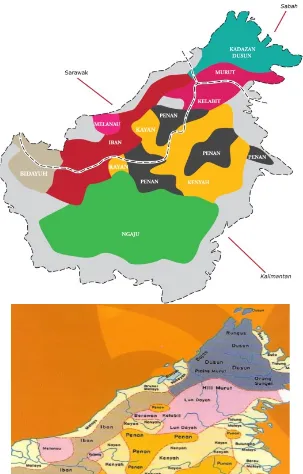

some of the tribes in which he has encountered to practice tattooing - the Dusun, the Murut, the Kadians, the Kayans, the Milanaus (Tatows, Balanian and Kanowit), Dayak (Dayak Darat and Dayak Laut). Sellato (1989) then further explains that Ibans, Kelabit, Kadazan, Dusun, Murut, Ngaju, Kayan Kenyah and Penan were documented to have practice some form of traditional tattooing15. Sigar (2014) also reports that explained that the Muruts or specifically known by their types as the Lun Bawangs to also have been practicing tattoos16.

13 Orang Ulu : upriver people and us a term used to collectively describe the numerous tribes that live upriver in Sarawak vast interior.

Welman (Unknown), Borneo Trilogy Sarawak: Volume 2, Booksmango. P. 138. 14 Keppel (2014), The Expedition to Borneo of H.M.S. Dido for the Suppression of Piracy, Bookpubber. P. 35.

15 Sellato and Perret (1989), Naga dan Burung Enggang: Kalimantan, Sarawak, Sabah dan Brunei, Elf Aquitaine Indonésie. P. 169.

Figure 3: Distribution of Tattoo Practicing Tribes by Oditous17

Keppel (2015) also explains that in many instances that the people in Borneo share the same culture and ideologies with little dissimilarities, though such claims can only been seen from an outsider, but those who are local will know the difference between a culture to another. This lumping of identity phenomenon is as Yen Espiritu (1992) terms as panethnicity where Americans tend to generalize 17 Oditous (Unknown), Distribution of Tattoo Tribes, Photobucket. Source:

Asian Americans to be a singular type of race, overlooking their background details18. However, having said that - many of my respondents explains that most of their origins come from various places in Sarawak, and have settled in Brunei for four generations19 explains that culture is the same, if not, it is only distinct in clan names202122.

Having said that, the older generation addresses the practice of tattooes, as ‘kerong’ is usually associated with the Ibans. The culture of tattooing however is slowly dying down since the intrusion of religion and education among the Iban, Murut and Dusun, which changed much of the perception of tattoos, making the ideologies that shrouds around the concept of tattoos to be different from the olden days.

There was not much secondary materials regarding tattoos in Brunei apart from interviewing the descendants of the tattoo practicing tribes, Dr Asbol (2015) explained that anything regarding tattooing is not considered as ‘Brunei culture’ and is only practiced notoriously by Ibans, explaining the exclusion is due to the fact that Ibans are not part of Brunei’s ‘puak jati’. Historians including Dr Asbol, further explains that the Ibans were not written in the Constitution as Bumiputera23 by the Bruneian authorities as the Ibans only entered Brunei from

18 Espiritu (1993), Asian American Panethnicity: Bridging Institutions and Identities, Temple University Press. P. 174.

19 Ah Joup Anak Rading (2015), Personal Interview. 20 Ibid

21 Nenek Angah (2015), Personal Interview. 22 Hujan Anak Muit (2015), Personal Interview.

Sarawak during the reign of the ‘White Rajah’ of the Brooke family24. Conversely some theorists believe that Ibans are still Bruneian by identity25, by socialization, by loyalty, and as seen in Figure 3, can be found within the geographical area of Brunei. Even as arguments state that Ibans are politically excluded, there are a number of Iban people living in Brunei such as places like Kampong Amo and Kampong Labi in which I have covered in this thesis, but as reported by Tassim et al (2013) the Iban population is dispersed all in the four districts in Brunei26 filling up to at least 6% equivalent to 19,400 people in 199727. And on top of that other ethnicities like those mentioned by Keppel (2015), Sigar (2014) & Sellato (1989) where the Dusun or the Murut (Lun Bawang) to be part of the 7 ethnic groups of Brunei28 – who used to practice tattooing.

CHAPTER 2: ETHNOGRAPHICAL FINDINGS

2.1. The Past: Kerong24 Minority Rights Group International (2008), World Directory of Minorities and Indigenous Peoples – Brunei Darussalam: Dusun, Murut, Kedayan, Iban Tutong, Penan, Source: http://www.refworld.org/docid/49749d48c.html

25 Leake (1989), Brunei: The Modern Southeast Asian Islamic Sultanate, McFarland.

26 Tassim et al (2013), Why is the Iban Tribe Excluded From The Official ‘Tujuh Puak Brunei’ and What Is Their Experience Being Born and Raised in Bruneian Society?, University Brunei Darussalam.

27 IBP USA (2007), Brunei Air Force Handbook, Int’l Business Publication. P. 37. 28 Ethnic Groups in Brunei: Brunei Kedayan, Tutong, Dusun, Murut, Belait, Malays and Bisaya (Government of Brunei, 1989).

In this section I have included three men aged from 51-70 from the Belait (Kampong Melayan), Muara (Kampong Mentiri) and Temburong (Kampong Amo), firstly to find respondents who practiced traditional forms of tattoos and to understand if the geographical difference would have an effect in towards the perception, traditions and culture of tattooing in Brunei. I will address tattoos in the context of how it is used in Brunei for this age group – ‘kerong’.

2.1.1 Nene Angah

He has always been a cheerful man with thick spectacles and always wearing a songkok29. But only until when I had a mission to finish this thesis was when I

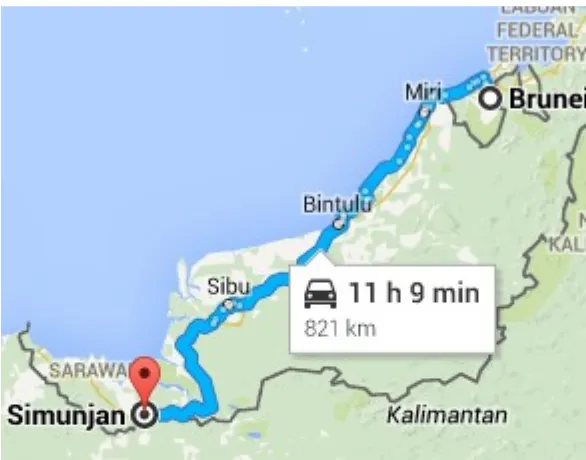

first found out that Nene Angah (middle grandfather : term to call sibling or in laws of grandparents30) is a convert that has a removed kerong on his arms upon conversion. Nene Angah has married into the family and migrated from Kampong Telagus, Daerah Simujian in Sarawak, and is now 59 years old and lived in Brunei ever since he turned 12. Married to my grandmother’s sister, it was easy for me to tap and gain permission as I have been close to Nene Angah – growing up, but most of our conversations were always regarding current life – school,

relationships and jokes.

29 Songkok or Kopiah is usually a traditional headgear that symbolizes Islamic malay men or boys. Rozan Yunos (23 September 2007), The Origin of the Songkok or ‘Kopiah’, Borneo Bullitien.

Figure 4: Simunjian to Brunei31

Nene Angah, started off explaining that traditionally, kerongs were created by mixing ‘karak kuali’ (which is the soot from cooking utensils) and then mixing it with coconut water. The needles is then poured into the kerong utensil (Figure 6) and then hammering it into the skin, and spoke much about the pain and then associating such pain to bravery. The variation of colors only goes around dark green depending on the skin tone of the kerong bearer.

31 Google Maps (2015), Simunjian – Brunei, Source:

https://www.google.com.bn/maps/dir/Brunei/Simunjan+Sarawak+Malaysia/@ 4.1316719,110.609308,6z/data=!4m13!4m12!1m5!1m1!

1s0x3218994b04b8b9d1:0x5dfe3580dd09dad6!2m2!1d114.727669!

Figure 5: Interior of Iban Longhouse32.

Notice the kuali in which the soot will be gathered.

© Bridgeman Art Library / Sarawak, Malaysia / Photo © Luca Tettoni

Figure 6: Needle and Hammer33.

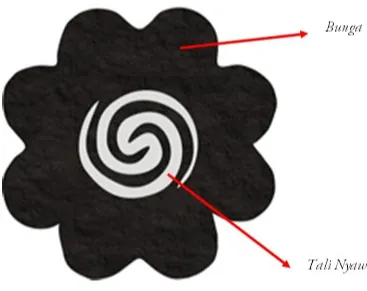

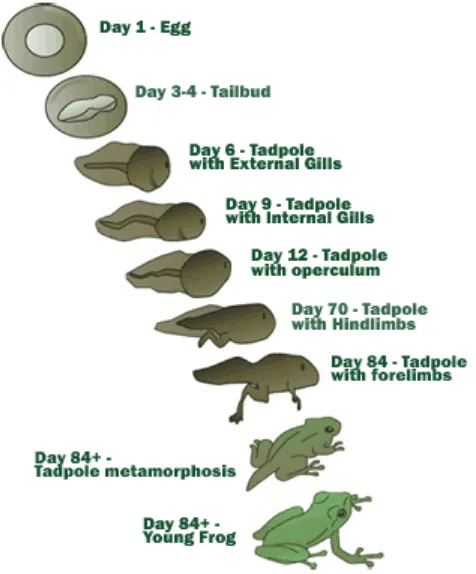

Some of the prominent tattoo styles are the ‘bunga terung’ that means eggplant flower (refer Figure 7 and 8), which is a symbol of masculinity, responsibility, bravery, having warrior-like qualities - a symbol of rite of passage for an Iban boy. The Bunga Terung is achieved when after they bajalai (source jalan - journey) in search of knowledge, wealth and after going for ngayau. The bunga terung must be worn as a pair as a balance to protect both sides of the body. The symbolic meaning of the Bunga Terung taken from the concept of the eggplant flower and tadpole egg fused together– where the frog will soon sprout hind legs (Figure 9) and then symbolically show that the man is going to ‘walk’ the jungle to fulfill

32

© Bridgeman Art Library / Sarawak, Malaysia / Photo © Luca Tettoni

Figure 1: Interior of Iban Longhouse,Bridgeman Art Library

, Image Source:http://www.magnoliabox.com/art/346166/interior-of-a-dayak-iban-longhouse, Date Retrieved; 3rd March 2015

their bajalai quests. The tali nyawa literally means ‘life coil’, which shape is derived from the tadpole’s transparent belly and then symbolically refers to the transition (Figure 10).

Figure 7: Bunga Terung34

Figure 8: The Eggplant Flower by Juan Buitrago35

Figure 9: The Growth of a tadpole to a frog by Neeha36

35 Juan Buitrago (Unknown), The Eggplant Flower, Dayak Impressions, Source:

http://dayakimpressions.com, Published on: 2nd January 2013. 36 Neeha (Unknown), The Growth of a Tadpole to a Frog, Source:

Figure 10: ‘Tali Nyawa’ the underside of the Tadpole intestines, in which the Iban has composed this to their ‘bunga terung’. Picture by Eldronius37

In the Iban context, one is bestowed a kerong based on their social achievements and merit and it signifies bravery and intelligence, which can be collected from various events. One of the main events, Nene Angah explained is the Ngayau38, an

event where Ibans go hunting for heads to showcase their braveness – and for the amount of heads brought back – that signifies their bravery and social standing – and this will be kerong-ed on his skin and his Ilang (sword).

37 Eldronius (2010), ‘Tali Nyawa’ The Underside of a Tadpole’s Intestines, Flickr, Source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/19749359@N00/4689950176/.

38 Ngayau is an Iban term for a traditional activity, which is compulsory for adult males where they will decapitate heads of enemies. Durin et al (Unknown), Simbolisme Ngayau dalam Motif Seni Tenunan Iban, Source: ,

The concept in kerong among the Iban is the ‘more the better’ social status the individual has, and these would be located around the arm, the torso, the legs, the neck and sometimes the face said Nene Angah. Individuals with neck kerongs are considered as most respected because such location is most painful – which equates to them being strong or braveness to sustain such pain.

Nene Angah also mentioned that kerong in the Iban society can be a form of signifier that can inform the society of the achievements that the kerong-ed person has which can increase the eligibility in marriage, gain economic importance also confirmed by Dr Dato Othman Yatim (2015) due to the reference that kerongs have. Apart from social purposes, mythologically, the Ibans are also required to obtain kerong, as this is the only way for their god – Betara39 to

differentiate the Ibans, said Nene Angah.

As from my understanding, kerong become a social unwritten law and a pre-requisite for the Ibans kerong, whereas only 1 out of 100 women indulge in having kerong, and only women who are around the age of 50 or more would have kerong, according to Nene Angah.

D; Do you think kerong is still carried out?

Nene Angah; No, mostly because it does not bring much benefit and kerong is against the religion not to mention barbaric and brutal.

Nene Angah, being a new convert seems to take his conversion seriously, and this phenomenon is explained by Riis and Woodhead (2010)40 that conversion involves stripping of existing loyalties, hopes, commitments in order to adapt the new joys of the new spiritual adaptations. So, with that, Nene Angah have stripped he ancestral beliefs and culture and has a stronger hold on to Islam’s teachings. However, his accounts cannot be taken in to explain most rejection to kerong – firstly because he has spent 47 years assimilating with other Malays

who are Muslim and is away from his longhouse tribe.

2.1.2 Ah Joup Anak Rading

After emailing Anna anak Durin from UNIMAS Malaysia41, I got some pointers to head to Belait in search of more kerong practitioners. At first, locals told me to go to Kampong Jabang and were surprised to find out this squatter based village42, mostly inhibited by Chinese manual workers – with no signs of individuals bearing kerongs.

40 Riis & Woodhead (2010), A Sociology of Religion Emotion, Oxford University Press.

41 Anna anak Durin, Senior Lecturer PHD, UNIMAS. Contact : danna@faca.unimas.my.

Figure 11: Kampong Jabang43

So I began to go around asking locals if there are any more leads regarding kerongs - until I ended up in Kampong Labi. Which is 50 minutes away from the

main road that connects the Tutong-Belait Highway.

Figure 12: Sign “Rumah Panjang Kampong Melayan”44

Figure 13: Entrance to Kampong Melayan45

My initial move was to search for the Ketua Kampung (head of the village) or in Iban terms Tuai46, to ask for his permission on interviewing his village. Ah Joup

anak Rading is a 71 year-old Iban who used to work for Shell, a Bruneian Oil

45 Hidayah Ariffin (2015), Shots from Labi, Personal Collection.

Company and now resides in his cozy Rumah Panjang (Long House) with a farm and orchard – was very open to the interview where he had so much artifacts from his ancestry.

Figure 14: Terabai - Sheild47

Figure 15: Ilang48

Figure 16: Traditional costumes now only used for Hari Gawai.49

Figure 17 : Pua Kumbu50 - A colorful weaving technique used in Borneo

used for everydat and ceremonial items decorated with different types types of patterns which is usually made by Iban women.51

49 Hidayah Ariffin (2015), Shots from Labi, Personal Collection. 50 Ibid.

Figure 18: a) Ah Joup in his full gear.

b) Ah Joup’s father during the Japanese Occupation

Figure 19 : Ruai - Corridor of the Rumah Panjang.

Figure 20: Ah Joup’s father at 22 in 194452

Figure 21: Ah Joup’s nephew with a a) dragon on his calves, b) Chinese scripts on his arms and the c) infamous Bunga Terung.53

Even with Ah Joup’s claim that he does not know much of the kerong culture, he still gives a clear picture of how the process of kerong is carried out. Similar like Nene Angah’s description – he further adds to the explanation that there are more variation of color apart from green, to blue to black– which depends on how deep the needle goes and the skin tone and type of the bearer. The colors however, does not signify any social importance – however only is the effectiveness of the kerong maker. Ah Joup then explains of the different types of tattoos on the top of his head which is the;

a) telingai (which will be situated around the legs and neck) b) ketam kukong (kukong crab)

c) bunga rambing d) bunga terung e) Kalong

He also explained that, it was better to make kerong in the morning, as it would cause less irritation towards the bearer, or sometimes, the rain helps too.

So when I got into probing things about gender practices, Ah Joup had the same reply again like Nene Angah. But then he explained that women would have like a line around her arms to signify from what tribe she is. But then he explained that men who did not have kerong were considered ‘pundan’ (sissy) explaining that;

Then Ah Joup explains that, men with tattoos are called ‘Bujang Berani’ (Brave Bachelors), which is also mentioned by Fox (2006).

So I asked Ah Joup, the same question I asked Nene Angah: is kerong still carried out? Ah Joup answered; No, it died out during the Japanese occupation. And it does not bring any assistance for the current times, we all need money and kerong

cannot provide us that. I used to remember that my uncles and grandfather

spending almost hours and days to fill parts of their body, and I think it is just a

waste of time when you can do so much more.

As I was about to leave, Ah Joup gave me a tour around his farm, introduced me to his grandchildren and asked me to write in a ‘guest book’. I also saw a plaque with signatures explaining that this Kampong and infrastructure was a ‘kurnia’54

from Pehin Haji Dani. From this visit, I have analyzed that Ah Joup is at a thirst to explain his heritage to the mass, making Kampong Melayan like a museum equipped with traditional artifacts and signage. All was well explained and versed but for the part when I asked about kerongs, where most of his explanation were just basic.

2.1.2 Awang Hujan Anak Muit

Figure 22 : Similar Lanterns from Labi55.

My next trip was to Temburong, where I interviewed Awang Hujan Anak Muit, 51 years old, who was the tuai of Kampong Amo. Before the interview, Awang Hujan was wearing just a simple white singlet; then he then came out wearing a green shirt with a picture of the Bruneian crest (Figure 23[c]). I began asking the same questions I asked Nene Angah and Ah Joup however it resulted to the same answers, especially on the methods and the gender practices. In many cases, Awang Hujan explained that he does not know.

Figure 23: Kampong Amo56

Due to his lack of information, I strayed from my script and asked; D; So why do you think you do not know much about this?

Awang Hujan; I have seen kerong happen before, but back then, there is no school to have all this written down – and if we were to write all this down, we still cannot

decide whether to have it in Iban, Malay or English as it would change the concept.

It’s a culture where parents to do not speak of, but only do. And for of the ideas that

I know are the ones I have asked before… I wouldn’t think questions like yours

would exist.

Awang Hujan then explains a different approach to the cosmology in practicing kerong.

AH; a lot of people believe that we do not have a religion, sorry for offending you ah… but believing in spirits is a religion too. And some kerong, as mentions by my

older family, have the potential to protect you from harms in the forest and these

orang halus (spirits), because we share this world with orang halus.

D; is kerong still carried out? Why?

AH; I am afraid not. Mostly because there is in no understanding, when we go to the pasar (market), onlookers will not understand why, but they would call you ‘orang

utan’ or ‘orang ulu’ and will give you stares as if you are not educated – but I bet,

when they know that these are for head hunting – I think they will think twice

*laughs*. But mostly its because of education – our society does not revolve around

Figure 24: UBD poster57.

Figure 25: Awang Hujan and his grandchildren58

From the uniform that he put on (Figure 23 and 25) when interviewing and the poster available (Figure 24), it is apparent that the ideologies of kerong has been affected by the hegemonic idea that having tattoo is unnecessary, as having a merit based system of recognition is not more relevant in the Iban society than to compare what kind of tattoo would signify one’s position in the society, which coincides with Ah Joup’s opinion. However, the impression of the hegemonic does 57 Hidayah Ariffin (2015), Shots from Temburong, Personal Collection.

not fully cover the Ibans of Kampong Amo – Awang Hujan explained that only 10% converts to Islam in the long house he is head of but this is not the reason why they do not practice kerong. Globalization plays a role in effecting the culture creating a form of independence to the hegemonic group of the society – this occurs once individuals leave their subsistence form of living to a globalized way of living. Some cultural deterioration inevitably happens when cultural integration occurs – in this case is the culture of kerong. Cultural integration is an ongoing effect since man started to travel and prominently occurring when the Silk Roads where cultures from the East fuses with the West – and with technology, it creates a new phenomenon creating a faster transferal of data causing some data to be considered irrelevant – in this case it’s the culture of kerong.

2.1.4. Analysis

In this section I will analyze the data collected for tattooing or rather kerong activities done in the past, by cross checking data from the three respondents as well as using scholar guidance from lecturers of UBD who are in the know of Brunei Darussalam’s past in kerong from the Historical Studies faculty in UBD by Dr Asbol and also using information from Akedemi Pengajian Brunei by explanations from Dr Dato Othman bin Yatim.

their location and availability – I have used the Iban tribe to explain the perception, history and cultural beliefs. In my interviews, that my entire three respondent believe that the kerong culture is not practiced in its full context anymore apart from it being a form of remembrance. Dr Asbol explains that the kerong practice has died out due to religion and education, changing the whole

perception of tattooing. However, the process of tattooing is not to a severe point as explained by Dr Asbol, but rather it has taken a different turn in concept, ideology, methods and design than the generic form of tattooing. Never the less, kerong has taken a new shape and new connotations from what it used to be,

with some remnant of many Iban concepts and way of life, minimally preserved, as seen Ibans still live in long houses, just as they did before, and still practice the welcoming lanterns. This explains that education (Ah Joup and Awang Hujan) and

religion (Nene Angah), plays a role in contributing to the progress of sociogenesis of tattoos in Brunei.

Then, from much deliberation, government intervention plays a role in changing the opinions of kerong. For example, concessions and ‘kurnia’ is made towards the ‘orang ulu’ especially tribes practicing kerong in hopes of elevating social welfare – where ideals of the hegemony has caught on to the tribes – by using soft power59. Ah Joup and Awang Hujang have been given houses by the government and to keep the grants, the tuais would have to adapt to the norms. As for Nene Angah, he was granted a free trip to Mekkah for pilgrimage, a what is now BND$10,000 trip with a controlled quota from the Saudi Arabia Ministry –

accepting only 200 pilgrims from Brunei each year60. So, the more adaption toward the ideals of hegemony – more concessions are granted towards them. And in adapting, activities that are deemed as ‘haram’61 would be some of the things that are shaved off first from the tribal cultures. Baker (2012) further explains that consumption of alcohol and eating of pork, and eating non halal meat and adultery is considered haram where the general population would choose to avoid these labels as going into haram ways would generate negative connotations towards the general mass. Kerong or tattooing on that sense is considered haram under the fatwa of Imam-Shafiie62. But having said that – there

are some branches of Islam that practices tattooing for example, Larsson (2014) explains that women in Upper Egypt tattoo their lip in signs of religious affiliation63. But even so, the concept of kerong cannot be practiced at a 100% way like before (however, as mentioned before, only as remembrance), as some of the motives were ‘ngayau’ or headhunting – which will be disruptive to Brunei. Rather, let kerong be a practice in Brunei that commemorates other things like in aged days such as for education achievements or intelligence, to sustain the cultural heritage for future generations. And if not, let the stories be told as stories in a cultural preservation center just as they practice in Sarawak (Awang Hujan, 2015)64 – to explain the sociogenesis to the mass of Brunei and the world, that kerong happened before the current contemporary tattoos did.

60 Hidayah (2015), Internship Experience during Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Brunei.

61 Baker (2012), The Oxford Handbook of the History of Psychology: Global Perspectives, Oxford University Press. P. 51.

62 Larsson (2014), Islam and Tattooing, University of Gothenburg Sweden. 63 Ibid. P. 245.

CHAPTER 2

NowOver the past 20 years, with the rise of high-speed data sharing and popularity accredited through the entertainment section becoming increasingly evident in the mainstream society – the role, situation and perception of tattoo changed vastly and constantly switching polarities from positive to negative faster as compared to before65. Shows like Miami Ink, or celebrities like Angelina Jolie have broken the stereotypical perception of tattoos being deviant by putting a positive connotation towards individuals with tattoos. However, there are also negative opinions that exists in contemporary times over different cultural locations as tattoos are connoted as prisoners Nazi Holocaust – where concentration camps these markings were used to identify a prisoner, the markings would give the impression to on lookers as if these are war criminals or being affiliated to ‘Hells Angels’. As seen in the section before, tattoos were seen as social determinants and will only be sanctioned and bestowed upon their achieving or receiving a status. In this section, the sociogenesis will take a shift from the traditional perception explained from the previous half of the chapter.

Figure 26: Angelena Jolie66

Figure 27: Miami Ink67

So in current times, Forbes (2001), Grief et al (1999) and Armstrong (2004) explained that most tattooing is motivated by the need for expression of identity, and its usage now can be considered as a form of conspicuous consumption – which is also the case in Brunei.

66 Mail Online, 'How do I say no?' Tattooed Angelina Jolie reveals her children want their own inkings but husband Brad Pitt is horrified, Retrieved From:

http://www.dailymail.co.uk/tvshowbiz/article-2867344/Tattooed-Angelina-Jolie-reveals-children-want-inkings-husband-Brad-Pitt-horrified.html#ixzz3Wux4Em6E, Retrieved On: 10th

March 2015, Published on: 10th December 2014. 67 Image Source:

In this section I have interviewed 5 different individuals regarding their perception, methods and culture of tattooing in Brunei, however I have skimmed the records to three to avoid repetition.

2.2.1 Arian

I came across a Middle Eastern looking boy who had initials on his hands, so I came up to him and asked for permission to interview him. My first participant, Arian is a 21-year-old permanent resident of Brunei, doing an Engineering Degree with two tattoos. First I start off with asking what types of tattoos he has – which was the name and initials of his parents decorated in Polynesian inspirations.

So I carried on to ask him – what was the meaning of his tattoos?

Arian; I am the only child of my parents, and we have been living in Brunei for 16 years. They are basically the only family I have and this tattoo which I made last

year is just to honor them… though at first they were very angry – but they got over

it… haha… Plus it is attractive, like body art and it is how I would like to express

myself.

D; why the Polynesian inspiration?

Figure 28: Arian’s Tattoos68.

When asked of some of the things that he considers before getting a tattoo, Arian mentioned that

Quality Price

The type of art and meaning the tattoo will portray

Arian mentioned that he made his tattoo in a home of a foreign artist who is on a solace trip to search for inspiration, in which he then explains of how tattoos are made is to first choosing a design, then stenciling it onto the body to position to liking, after that tracing the stencil using the tattoo machine while wiping the extra ink off until the tattoo is complete. “Whoever said that tattooing is not painful, it is straight up lies”, he said.

Figure 29: Modern Tattoo Device in which I took a picture of last June at Musee Quai Branly69.

Arian did not know and traditional Bruneian tattooing or could he explain it, but he did mention about Iban Kerong as a form of traditional tattoo in Brunei in Brunei. But has made a vast explanation about the contemporary forms of tattoos that are available now:

Memorial; This is the traditional portraiture, picture of an object, or a connotation of usually someone special that has passed away.

Portraits: This is generally a face tattooed on the skin.

Oriental: Usually Asian themed tattoos which usually works around koi, samurais, cherry blossoms, dragons, lotuses and such.

Religious: Religious symbols or quotes.

Tribal: These styles of tattoos are the groupings of tattoos from Native Americas, Polynesia, Micronesia or Hawaiian.

Realistic: Realistic tattoos refer to the section of tattoos that is true to the picture, as opposed to animations or cartoons.

Cartoon: Inspirations that is usually taken from their childhood or favorite cartoons as whimsical.

Lettering and Ambigrams: This is one of the most popular forms of tattoo where it could mean anything or say anything and it is simplistic, with variable options of fonts and styles.

Black Gray: Shadings of black and gray used to bring three-dimensional pictures to life instead of using colors.

Gray Wash: This may seem similar to the gray wash however, it is more on the play of shades.

Color: This method of tattooing uses different colors as opposed to the gray wash and black and gray.

American Traditional: The American Traditional however is the two dimensional and low intricacies, which was made popular due the sailors of 1800s. These consist on bold colors; blue-black outlines and filled with red, green and occasionally blue yellow brown purple and no shading. Neo traditional: The neo traditional is the revised concept of the

American traditional tattoos with a better and extensive color palate, which is fused with a combination of hip-hop, graffiti, jagged edges and bubbly lettering.

Fillers: These are used to fill in the gaps in cases where the tattooed wants to complete a sleeve or leg.

There is no capping price to what is considered the cheapest and most expensive, said Arian, it all depends on the design and the artists charge; but his was $90 and $200. The more colors used, or intricacy of the design will affect the price of the tattoo. A lot of things can affect the price of tattoo, and it was a point, which could elevate the status of the bearer.

matter the most to me, and I will put my wife’s name on my chest one day. And so

far I have not really thought about what others think about me, and it doesn’t

really affect me”.

2.2. Bryant

Figure 30: Some of Bryant’s Tattoos70

There were roughly 10 tattoos on his body and he got most of them locally and internationally and then I asked him why did he get them - explained that most of the tattoos he got was to commemorate the people he loves in his life (i.e. father, mother and grandmother, seen in Figure 30 [a] and [b]), a ‘postcard’ souvenir which signifies the places he has visited and just some satirical ones such as the envelope and shark note.

Bryant then also mentioned of the things that one has to consider when making tattoos – which falls in line with what Arian had mentioned (Quality, Price, The type of art and meaning the tattoo will portray) with an addition to hygiene. Then I asked him if he knew the types of tattoos that I have asked Arian earlier and he only managed to answer three, because that was the concept that was more likely to be attracted to. And he mentioned that, ‘tattoos is like wearing clothes, I don’t think you can just mix and match it, moreover you have to look at this for an amount of time, so its wise to get an experienced tattooist if you ever plan to mix and match something or else you are going to regret’.

Unlike Arian, Bryant knew some traditional tattoos that are carried out in Brunei, mentioning that Brunei did have a phase where group members and gang members usually the Chinese, would have the same tattoo to signify that they are from the same club, group or gang. He then showed a picture of his grandmother, which he explains is inspired by the Sabahan culture with traditional Iban motives.

And lastly, I asked him, so what is the perception that the tattoos imply to him and to the people around him, he said; “it never stopped me from getting to places, achieving what I want in life, if anything I want my son to have it too. Of course

with his own money… hahah tattoos are not cheap.”

2.3. Ilham

Figure 31: Ilham71

He entered the café with a huge sweater on, which covered all his tattoos. Ilham then started explaining that he had his first tattoo when he was 20 and has been adding to the canvas ever since, where he has 15 tattoos on him right now. His first was the Hanya Mask (Figure 31b), where he explained that it is from a Japanese folklore where the mask represents an intense evil of a woman turning into a devil through jealousy and hatred72. I asked him why, and he said, I don’t know.

D; why did you start getting tattoos? Ilham; no reason.

D; what are the meanings of each tattoo?

Ilham; I only got them for no reason and just because they are beautiful. But apart from that – I have two actual portraits of my two kids. I love them.

Then Ilham started telling that he got these tattoos all over places that he has visited just like Bryant mentioning that one of his most expensive tattoo costs him SGD $3000 – and then he explains that calculatedly all his tattoos have amounted up to BND $10,000 more or less. ‘I think I have an addiction’, Ilham said.

When asked about any traditional tattoos – Ilham explained that he does not really know any traditional tattoos but he mentioned the word ‘kerong’ and knows that it is practiced among the Iban community.

I then ask Ilham of so what is the perception that the tattoos imply to him and to the people around him, and he simply said ‘I have never really given a thought about it, I see people with tattoos and without tattoos but I don’t have any opinions

about it – I love my tattoos and that is all I know’.

Analysis

I have interviewed 6 people in this section and have chosen three of the most unique responses to avoid being redundant – as most of the responses I got from my respondents were the same. I will then try to analyze their response individually.

explains that this response is that tattooed people feel that the images portray their self-redefinition73. In many situations, before getting a tattoo, individuals would have to consider over a period of time of what they choose to inscribe on – and the aftermath is what defines them. However, as seen, Byrant and Ilham, would get tattoos after they travel, as a form of souvenir, where, it would not be a situation that has more initial thinking that most regular people. Having said that, it could be their form of expression of conspicuous consumption74 -portraying their travelling diary in scripted on to their body. In relation to this, each country has a generic form off tattoo style for example75,

Figure 32: Yantra Tattooing from Thailand76

73 DeMello (2003), Tattooed: The Sociogenesis of a Body Art, University of Toronto Press: United States. P. 203.

74 Veblen (2011), Theory of Leisure Class, Books on Demand. 75 Ann & Julien (2014), Tatoueurs Tatoués, Musee Quai Branly.

Figure 33: Kalinga Tattooing from Phillipines77

Tattoo enthusiasts get a form of satisfaction and again, decorate their individualism after getting these country-specific tattoo styles.

During the interviews, I have notice that most of my respondents have at least one piercing, which triggers me to ask why. The types of piercings these people practice are usually the ‘plug’ type, but in many cases it would only be one stud. The usual motivations for these piercings are ‘to complete the look’ or ‘an addiction to the needle’, ‘it is cheap’ or for attractiveness. Salvation Tattooings, explains that piercing and tattooing works hand-in-hand in one establishment78.

77 Lars Krutak(2009), The Last Kalinga Tattoo Artist of the Philippines, Source: http://larskrutak.com/the-last-kalinga-tattoo-artist-of-the-philippines/

Both come hand in hand in current times as a norm79. And in tribal societies too, practitioners have both tattoo and piercings.

Not all respondents know the different types of contemporary tattoos, however, through explanation and observation, the American traditional tattooings are the main types of tattoos that Bruneians carry out. Mainly due to the fact that these are the tattoos carried out by TV shows explained earlier and these are the only expertise tattoos that the tattoo artists in Brunei are good at80.

Most of the tattoos that my recipients have are made in homes of tattoo enthusiasts or abroad – especially in Singapore, Malaysia and Thailand. In which cases they pay around BND$100 for the cheapest and can go as expensive as BND$3000.

Towards the last part of my interview, I would ask if my younger respondents would know any form of traditional tattoos in the context of Brunei, and only two out of six knows the traditional tattooing practiced in Brunei – one because they come from the tribal families and are hardcore enthusiasts. In relation to this, Awang Hujan81 explained that this is due to the fact these cultural teachings are not taught at institutions, let alone practice the kerong culture, as it does not confer to the hegemonic culture.

79 Gould (2014), Tattoos and Piercings: The New Norm, The Quirky Daily. Published on: 12th November 2014.

CHAPTER 3:CHANGE

As seen in the previous chapter, there is a shift in tattoo practice within the concept of Brunei Darussalam. In this chapter however, I will talk about the elements that causes the changes of tattooing.

3.1. Globalization

community. Those who were exclusive and moving in the Brunei context were some tribes of the Iban and Dayak, practicing subsistence farming. The first hit of cultural wash, was when the ‘Orang Ulu’ bargained with the ruling centers for state concessions where some closer villages would assimilate to the center more than those who are further away from the center.

Then was colonialism of Southeast Asia, which then taught the locals on the norms and values and possibly applying the western frame, then teaching them ways of settlement as opposed from the subsistence way of living. This has deteriorated the traditional practice of tattoos to a more ‘sanitized’ practice, changed the styles in ways that it has become more varied and fused with

international styles, stopped the ngayau activities and gave various perception to tattoos where if one were to have traditional tattoos – they would either be connoted as barbaric and backwards82.

3.2. Religion

Religion and culture affect each other in various levels, as it shapes each other system of beliefs and practice – causing syncretism – which causes the changes in the culture of tattoos in Brunei. Barker (2012) explains that Brunei’s culture has been influence by four dominating periods of animism, Hinduism, Islam and the West83, so, Ibans, Murut, Dusun and others practicing tattooing, who have stayed in Brunei have gone through some degree of assimilation to the melting pot 82 Dr Haji Awang Asbol Haji Mail (2015), Interview.

boundaries that Brunei have outlays since the dawn of commercial exchange towards the independence during the 1st January 1984, some in much pressure84 to convert to convert to either Islam or Christianity and some to maintain their ongoing influence of ethnicity.

Sir Henry Keppel (2014) explains that conversion might have induced tribes to lay aside their ‘barbaric’ customs. Christianity and Islam had varying effects on tattooing to different groups of people, as it is a move away from the animistic beliefs they once had - some went to the banishment of tattoo practice as

Leviathan and Islamic exegesis teachings does not agree with the practice of self-mutilation and deliberately scarring the self- tattoos.

‘’Do

not cut your bodies for the dead or put tattoo marks on yourselves” (New International Version, Leviticus, 19:28)”85.84 International Religious Freedom Report (2012), Brunei Darussalam

International Religious Freedom Report, Department of State, Berau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor : United States. Source:

http://www.state.gov/documents/organization/208428.pdf. P. 4.

Figure 34: Exegesis from the Al-Quraan86.

hide his tattoo – though Ilham made it clear that he is only adopting tattoos for his own satisfaction, Brunei was not at a secular place to accept his tattoos.

With that, some my recipients further explained that their religion orientation is not at all shifted when they get tattoos, explaining that the meaning can be distorted and that they accustom their belief that it is their sin between him/her and God.

Kerong nevertheless mostly died out as it was highly intertwined with

headhunting and this was an act that is highly against teachings of Islam and Christianity. By implementing religion into the political institution, ‘morals’ deletes the need to go for headhunting – replacing social mobility with other religious activities of good deeds – such as alms giving, or reading the holy books or charity movements. However tattooing still persist taking a whole new

concept that is far from the traditional kerong.

The advancement of technology made it possible for people of different social class to practice tattoos87. As explained by Nene Angah, Ah Joup and Awang Hujan tattoos were made by using the dark part of the kuali and by mixing it with coconut oil, and then hammering it into the skin only when receiver gets some sort of social achievement and can only be done by a skilled tattooist with a vast knowledge in making tattoos. But now, those with the electronic tattoo machine with a flair for the fine art can charge anyone who is willing to pay can carry out tattooing without the hurdles of cultural elitism.

Nene Angah, Ah Joup and Awang Hujan did not touch on sanitization, but when enquired, they explained that the tattooing process has never implicated any form of harm to those who made tattoos. This was because the ingredients, they claimed – were to be natural88. Now, however, sanitization has become an issue for many; where there are cases reported in Mason (2003)89 – diseases like hepatitis or STD’s can easily be contracted. This perception, increased as tattooing becomes commercialized than an act of spiritual rite de passage.

However, with the massive number of cleaning and sanitation products – hygiene is not an impossible goal.

Tattoos can now be easily practiced by with scientific advancements, and as said before, can be practiced by more than just one culture, group or events. For example, before tattooing is exclusive to tribal members but now, Malays,

87 Porcella (2009) Tattoos a Marked History, California Polytechnic State University.

88 Awang Hujan (2015), Personal Interview.

Chinese, Tutongs, Belait Bisaya who wish to have tattoos can get tattoos without having to achieve a specific goal like – headhunting.

3.4. Politics

Hegel believes that the state shapes the society – supported by Levy (1999) explaining that – “the organizational dimensions are politically mediated and changeable”90. And in agreement to that, the politics of the country plays a role in affecting the mindset, acting like a state for the minds of the citizens. After 1st January 1984 Brunei has adopted the political concept is based on Melayu Islam Beraja (MIB) maintaining a political conservatism91 and concepts have become more heightened over time. Brunei’s politics is a combination of religious and royal roles that seeks to contain conformist Islam, where most businesses are state owned making the government the hegemonic group – and with the widespread ideology of practicing Islam and Malayness as the identity of the country, tattooing is not really considered a common practice for the country due to how it is not approved in most Islam sects. In this case the social conformity covers to even those who are not Muslim or Malay to avoid social critics.

However, after checking the government laws through Sankaran Halim Advocates and Solicitors92, both Civil and Syariah, there are no records that can convict those who practice tattoo, as it is a cultural practice. Other account of cultural

90 Levy (1999), Tocqueville’s Revenge: State, Society and Economy in Contemporary France, Harvard University. P.8.

91 Leifer (2013), Dictionary of the Modern Politics of Southeast Asia, Routledge. p.4.

practice that may fall in this line is the female circumcision93 – which is an activity that is still prevalent until today. But unlike tattoos female circumcision does not get any excerpts that it is forbidden as much as tattoos – although some may argue that female circumcision to fall under self mutilation, which then can intervene just as much as tattooing. Meaning to say, tattooing practices although it has no official statement that it is condoned it receives informal negative social sanctions due to the fact that Brunei practices Melayu Islam Beraja.

3.5. Education

Education plays a role in changing the ideology, styles and perception of tattoos in Brunei – firstly on how Islam does not tolerate tattooing and secondly on how tattooing is not taught by the structure to the next generation. In Brunei,

religious schools are made compulsory even for children who are not Muslims94 through the implementation of South East Asia Primary Learning Metric (SEA-PLM) in 2012. And on top of that, students are not taught of the cultural diversity in Brunei apart from the teachings of MIB. Such implementation and practices causes the change of opinions in tattooing towards a less important aspect of life, and to have a perception that tattooing does not exist within the cultural context of Brunei – which is confirmed by my ‘the Past’ respondents, saying that the legacy of the heritage is not explained to their younger generations. The ‘Now’ respondents however, gets their form of education regarding the tattoos from the

93 Bandial (2012), Female Circumcision is Cultural Practice, Brunei Times, Published on: 16th June 2012.

global media – causing them to get tattoos that are not related towards the traditional practicing.

3.6. Economics

In the past, the economy of the ‘Orang Ulu’ depends of the physical surroundings for sustenance, so for the tribes that practice tattoos, the mode of economy was based on agriculture, fishing and hunting. The frame of society of a tribal

economy is not similar to the modern concept, so the progression in times made the tribal society more reliant towards money and global economy, divorcing them from the dependence to Mother nature. With progression, the frame of society shifts as well. Ah Joup (2015) explains that he is not bothered to make tattoos on his body as it does not benefit him like an actual work and job does, where as he explains that his forefathers needed the tattoo signifier in the community to know who weaves the best Pua Kumbu or who hunts for the community. But now, Ah Joup explains that, one can get cloth like the Pua Kumbu or just go to the supermarket to get food. So from here, the economics of the society’s reliance towards tattoos

there is a difference between potential identities and bought identity95 - in relation to that, my respondents are able to get tattoos that signify the highest position in the society by paying a tattooist to replicate the ‘bunga terung’ without going for ‘ngayau’.

So the sociogenesis of tattoo in terms of economy shows that the reliance towards money has changed the frame of the society making traditional culture less relevant and objectified – from a concept where getting tattoos is a social achievement and a ritual that is priceless.

3.7. Gender

Tattooing as explained by De Mello (2000) is ‘…permanent, painful and

masculine’96 and traditionally associated with masculinity. In the context of Iban Brunei, it is explained that in the past, women are not needed to get tattoos however, does get one on her arm to signify that she is from a specific group of tribe and her ability to weave Pua Kumbu. For men, it is seen as a symbol of courage or what Armstrong (1991) would explain as a ‘badge of courage’, and as Nene Angah explained that tattooing is also necessary to get married, as a way of attracting women.

95 Davidson (2013), The Consumerist Manifesto: Advertising in Postmodern Times, Routledge. p. 192.

However, now, women practice tattooing at her will to signify her individuality and fashion. Raymond (2011) explains that most women get tattoo as a form of jewelry or accessory however, her perception towards the society is that she is more likely to be seen as a deviant as compared to their male counterpart97. In Brunei, however, male and female carry out tattoos as a shared gender activity, equally frowned by the mass but however, females tend to get more thumbs down as compared to men, generally due to the MIB perception.

In terms of design major researches explain that the designated tattoo designs accorded to gender falls on the outline of the ideology of the society. In terms of the Iban culture, there were no specific rules in the design of tattoos except for the ‘bunga terung’, however, during the current times, pictures or abstracts that is connoted with the global idea of femininity is the basic general idea of what is feminine and masculine – which again needs revision concepts of gender is a subjective matter. So to some extent, with the ambiguity of the tattoo styles, there are no specific rules on designs for both epoch of time.

In this section the concept changes – from a signifier of gender in the past– to a form of equally shared activity, with the same concept of not having any gender determined tattoo designs.

3.8. Social Perception

During the past, the acquisition of getting tattoos was something that is

bestowed during the rite of passage the type of perception that shrouds around those who have tattoos, usually among men – is understood that through the text that when a men has tattoos or kerong he is supposedly brave and with

knowledge. So the place of an individual with tattoos is elevated among peers and to those who understand the concept. This is also the case as getting the ‘bunga terung’ or ‘kalong’ is a process that is given or made by a sole practitioner in the society – making it a rare and special occasion. The perception however – on the Iban tattoos shift, as explained by Dr Asbol, Awang Hujan and Nene Angah as to explain that the previously dignified perception of traditional tattooing shifts into a signifier of ‘barbarism and uncivil’.

Tattooing receives a popular increase in the media and to how it can be freely done now, however sociologists such as Josh Adams argues that it still retains some of its marginal characteristics – where the society still relates tattooing to deviancy rather than the concept of ‘self expression’. What more is how Brunei is overpowered by the hold of MIB. For this investigation, I have questioned my tattooed respondents if there were any negative feedback from the public onlookers, my respondents usually explain that it is usually a couple of stares, however, job opportunities are never stunt. But when asked of the public, they usually explain that it does fit with the ‘Asian or Bruneian’ identity or that tattooing is a sin and ‘no comments’98.

The perception of tattoos changes from a dignified rite of passage – then it evolves towards an ‘uncivil’ practice and then remains the same as the grasp of MIB is still resilient, but not to a stage where it is views at the worst form of criminality. Technically, Brunei allows the acts of tattooing but does not encourage it to be part of a common culture.

3.9. Media

Porcella (2005) explains that there is much increase in the practice of tattoos in most major medias in the world since 199099. As mentioned in the introduction, most series like the Miami ink – or major stars like Angelina Jolie, Justin Beiber and David Beckham gives a platform for the viewers to be educated of tattoos and form an opinion about it. However, the media has been argued in many sociological debates as one to shape the ideas of the mass – propaganda. In many cases, the usual media explained by Porcella (2005) attempts to persuade and change the idea of tattoos by strengthening the appeal as A-List celebrities have tattoos. The effects of media can be seen in Brunei as my respondents from the ‘Now’ section are practicing designs that are out of the traditional Brunei context – with the same ideologies that are portrayed by the media – that tattoos are a form of self expression.

But having said that, Brunei has a different form of media, which also creates a confused state towards the mass – the conservative Islamic way of thinking.

Newspapers, television shows, radio broadcasts are all tailored to fulfill the MIB concept. As an example – ‘Illegal’ held, Tattoo Parlour Uncovered by Brunei Times (25th July 2010) the censorship and bad connotations about tattoos are discreetly implemented in the Bruneian media, by using terms such as Illegal as a headline. But never the less, for such destructive connotations that exsists in Brunei– respondents explain that the form of negative sanctions that they get is not as bad. Arian explains that, the types of responses he gets is usually, ‘why do you do it?’ followed by a confused face.

Matthews (2002), explains in Global Culture/Individual Identity: Searching for Home in The Cultural Supermarket100 – for this, there is the global culture and national culture, which is this case puts Brunei in a position to have a varied form of perspectives regarding tattoos. But when put in the element of traditional kerong – younger respondents feel at lost or unattached towards the concept,

whereas the older generations feel like it is not relevant. So, this creates an illusion as if the concept of tattoo is only brought on from the idea that it is only taken from the global culture – rather as some would say ‘Westernization’ – duly due to the fact that the gap between current generation and the previous

generation have decided to sever the ties. But all in all, the concept of tattoos swings from positive to negative at a global platform101, which is also the case for Brunei.

100 Matthews (2002),Global Culture/Individual Identity: Searching for Home in The Cultural Supermarket. P. viii.

Conclusion

All in all, globalization, religion, scientific advancement, politics, education, economics,

gender and perception are some of the concept that has a form of complex relationship

between each other and all affects and influenced in changing and promoting the sociogenesis of tattoos.

CHAPTER 4

LITERATURE REVIEWstimulated, videography exhibitions. As much as this exhibition has a lot of sociological and anthropological values, I feel like there should be an addition to Brunei’s perception as an extension to this intricate collaboration because the section on it was only rounded as BORNEO, possibly a religious perspective to tattoos. I think Brunei has a battle with the idea of MIB and the concept of self-expression and identity in this section – which deserved more than just a one-meter wall. In my thesis I will cover a detailed explanation on Brunei as much as Ann and Julien, the curators explained on other cultures.

Need To Know: Body Piercing and Tattooing by Paul Mason (2003) – A simplistic

explanation that covered many basic knowledge on tattoos showing a lot of vivid pictures. This handbook is useful in conveying simple data and is a fast read covering the history, introduction, implication, contemporary view, and situation with law, stigma and health. My thesis will use Paul Mason mostly as an

introduction as a material for understanding the basics of tattooing. However, it is not an in depth coverage and very broad as it does not cover a specific case study. In my thesis I will cover a detailed explanation on Brunei with topics that Paul Mason have covered but I will have a more extensive explanation, but with the effectiveness of Paul Masons methods of conveyance.

The Polynesian Tattoo Handbook: A Guide to Creating Custom Polynesian Tattoos

towards the in different body parts. The usage of the language creates a sort of depth of knowledge towards the author. The author also uses the element of photography, which makes reading this book an interesting read. Gemori also explained the gender meanings of Polynesian tattoo in which I feel is effective. My thesis uses the visual approach that Gemori uses to explain tattooing in Brunei

Inked: Tattoos and Body Art Around the World by DeMello (2007) – I will be taking

the gist of page 290 – 291 covering the Iban section – which is quite a short input as compared to Gemori’s Work. Then I will take into account of page 320- 322, where DeMello mentions further on Islam. Having said that, DeMello’s work is an encyclopedia of tattoos from all over the world and throughout history written in a short gist – and she does not cover on tattooing in Brunei as what I will be covering.

Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgment of Taste by Bordieu (1984)102 – In a short text in DeMello, she explaines of using Bordieu idea on tattoos. Bordieu in DeMello, connotes that tattoos belong to the ‘poor working class bodies, as only sailors, convicts and other members of the working class or underclass wore tattoos103’. This idea is a debatable topic is which I will plan to use in my essay because to some extent this idea is embodied in globalization. Pierre Bordieu made that statement during the 1980s where in this thesis; I will explain how tattooing has become more glamorous due to the media portrayals. So, my thesis

will cover the contemporary view of tattoos, as well as the past – using Brunei as a case.

Encylopedia of Body Adornment by DeMello (2007) – Like her previous work that

I have used for my literature review, DeMello gives a gist of different study cases, where in this book she talks about different body modification in many cultures, traditionally and in in contemporary societies. DeMello aslo has arranged the datas in this book as a dictionary for ‘body adornment’. The book is not

straightforward and it requires trigger words so that the reader could jump from page to page in order to patch the needed information. My thesis is a

straightforward work, not as a referral point as this version of DeMello.

Borneo: Sabah – Brunei –Sarawak by Thiessen (2012) – Thiessen writes about

the an ethnographic study on the people of Borneo. The form of literature in this book is quite simplistic because it is written for travel guiding purposes. Thiessen does explain a bit more about the origins and rule of Brunei, however in a very bleak light in page 131. The input of tattoos is only a mere mention on how the indigenous people – but I would like to include Thiessen as there is an adequate amount of statistical data in of the placing of tribes in Borneo. From there, I can locate the tribes, which still carry on with the tattoo culture.

cosmology of the Polynesian world, using sources from past missionaries and his own field work. He then makes a clear-cut explanation of the shell like

immanence of the cosmology comparing it to the Christian world. However, his work uses a lot of words that are not transliterated properly excluding certain types of readers. In my thesis I will try to explain the Iban words to the next best thing.

James J. Fox (2006), Origins, Ancestry and Alliance: Exploration in Austronesian Ethnography for Chapter 5 “All Threads are White Iban Egalitarianism

Reconsidered” (Clifford Sather) - talks about the hierarchal statuses of the Iban statuses which is dubbed to be egalitarian by many European travellers during the past. The chapter goes on a constant debate discussing to what extent does the Iban culture practice equal rights and opportunities – as well as explaining the culture concept bit by bit – which is effective to validate some of my findings from the respondents. Initially, I thought this excerpt was redundant because it talks about the equality of the Iban society. However, after collecting information from my respondents, I understood Fox’s writing on the concepts of ‘bravery’ and ‘warrior like’. Having said that, my thesis will be a progression of this effective text – that talks about the sanctions after their war and display of their

‘egalitarian’ relationship amongst each other – and how they translated this relationship on their bodies as tattooes.