www.elsevier.nlrlocateraqua-online

ž

Growth of blacklip pearl oyster Pinctada

/

margaritifera juveniles using different nursery

culture techniques

Paul C. Southgate

), Andrew C. Beer

School of Marine Biology and Aquaculture, James Cook UniÕersity, TownsÕille, Queensland 4811, Australia

Received 29 July 1999; received in revised form 11 November 1999; accepted 9 December 1999

Abstract

Ž .

This study was based on blacklip pearl oyster Pinctada margaritifera juveniles, that were hatchery-reared and 8 months old. They were held for 5 months in suspended culture using five

Ž .

culture techniques: in 24-pocket juvenile panel nets PN24 ; enclosed within 5-mm plastic mesh

Ž .

‘inserts’ placed in the pockets of eight-pocket adult panel nets PN8 ; in 5-mm plastic mesh inserts

Ž . Ž .

without being placed into panel nets INSERT ; in plastic mesh trays 55=30=10 cm with lids

ŽTRAY ; and by ‘ear’ hanging EAR . Survival was high during the experiment and ranged from. Ž .

100% in PN24 and PN8 to 90.6% for the INSERT treatment. Juveniles held in 24-pocket nets

ŽPN24 and ear-hung juveniles showed the greatest growth during the experiment, and had.

Ž . Ž .

significantly greater dorso-ventral height DVH and wet weight WW than oysters in all other

Ž . Ž .

treatments P -0.05 . Pearl oysters held in inserts within adult panel nets PN8 and alone

ŽINSERT showed the lowest mean DVH and WW. This probably resulted from heavy fouling by.

rock oysters associated with mesh inserts. When other factors such as cost, ease of construction and degree of fouling were considered with growth and survival, the five nursery methods were ranked in decreasing order as follows: PN24)EAR)TRAY)PN8)INSERT.q2000 Elsevier Science B.V. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Pearl oyster; Pinctada margaritifera; Juvenile; Growth; Nursery culture

)Corresponding author. Tel.:q61-7-4781-5737; fax:q61-7-4781-4585.

Ž .

E-mail address: [email protected] P.C. Southgate .

0044-8486r00r$ - see front matterq2000 Elsevier Science B.V. All rights reserved. Ž .

Ž .

wild Sims, 1993 using spat collectors. Spat usually remain on collectors until they are

Ž . Ž .

large enough to be ear-hung, when dorso-ventral shell height DVH is between 30

ŽPreston, 1990 and 90 mm AQUACOP, 1982 . Ear-hanging is the predominant method. Ž .

for holding P. margaritifera in Polynesia. Oyster juveniles removed from spat collectors are attached individually with wire or monofilament fishing line to ‘dropper’ ropes suspended from a longline. This process involves drilling a hole through the posterior auricle or ‘ear’ of the oyster shell, and tying the shell to dropper ropes. The dropper

Ž .

ropes, called ‘chaplets’ AQUACOP, 1982; Preston, 1990 , are hung from the longline at 1–2 m intervals. P. margaritifera juveniles generally remain on chaplets for the rest of their time in culture.

This very successful technique negates the need for nursery culture. As such, the development of nursery culture techniques for P. margaritifera juveniles has received little attention and very little information is available regarding suitable nursery methods for this species. However, the last few years have seen increasing emphasis on hatchery

Ž .

culture of pearl oyster species Gervis and Sims, 1992 and a number of studies have

Ž

reported successful hatchery culture of P. margaritifera Alagarswami et al., 1989;

.

Clarke et al., 1996; Southgate and Beer, 1997 . Because of these developments, there is increasing need to develop suitable nursery culture methods for P. margaritifera.

This study assesses growth and survival of P. margaritifera juveniles using five different nursery culture techniques.

2. Materials and methods

This study was conducted in Pioneer Bay, Orpheus Island, north Queensland,

Ž X X .

Australia 18835 S, 146829 E using 8-month-old hatchery-produced juveniles.

Approxi-mately 1000 Pinctada margaritifera juveniles were graded according to shell size, and a

Ž .

subsample of 40 randomly chosen individuals was used to determine mean "SE

Ž . Ž

dorso-ventral height DVH, 41.5"0.6 mm , antero-posterior measurement 40.5"0.5

. Ž .

mm and wet weight WW, 7.5"0.3 g at the start of the experiment.

This experiment assessed growth and survival of pearl oysters held during nursery

Ž .

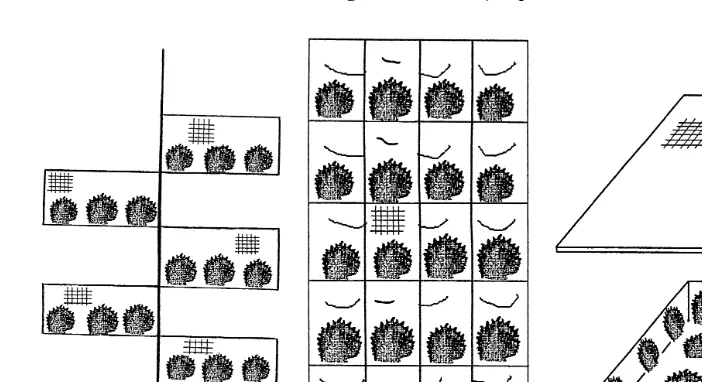

culture by one of five methods. Two of these methods involved the use of panel pocket

Ž . Ž .

nets Fig. 1 , which consisted of a powder-coated steel frame 750=500 mm covered

Ž . Ž .

with polyethylene mesh, sewn to form pockets Fig. 1B . Juvenile panel nets PN24 had

Ž .

Fig. 1. Nursery culture methods used for P. margaritifera juveniles. Asplastic mesh inserts attached to

Ž .

‘dropper’ rope INSERT ; Bs24-pocket juvenile panel net with 750=500 mm steel frame covered with 25

Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž .

mm mesh PN24 ; CsPlastic mesh tray 550=300=100 mm TRAY ; DsEar-hanging EAR .

Ž .

adult panel nets had eight pockets per net PN8 and were covered with 40-mm mesh

Ždiagonal measurement 57 mm . Pearl oysters held in PN24 were placed individually.

into the pockets. Juveniles held in PN8, where mesh size prevented placing the oysters directly into pockets, were first placed within ‘inserts’ made of 5-mm plastic mesh folded in half and clipped together along three sides. Three juveniles were placed into each insert so that each of the panel net treatments held 24 juveniles per net. In a third

Ž .

treatment INSERT , juveniles were held in inserts without being placed into the panel net; three juveniles were placed into each insert and the inserts were tied to a ‘dropper’

Ž . Ž .

rope Fig. 1A . In the fourth treatment TRAY , juveniles were held in plastic mesh

Ž . Ž .

trays 550=300=100 mm with lids Fig. 1C , at a density of 24 individuals per tray.

Ž . Ž .

In the final treatment, juveniles were held by ‘ear-hanging’ EAR Fig. 1D .

Monofila-Ž .

ment fishing line 24 kg was tied and knotted in 12 places through 8-mm rope to form a chaplet accommodating 24 oysters. Each juvenile had a 1-mm-diameter hole drilled through the posterior part of the shell through which the monofilament line was passed and tied. A distance of approximately 5 cm was left between the oysters and the rope. Each treatment had four replicates and each replicate held 24 oysters. Replicates were suspended from a longline on separate and randomly allocated dropper lines at a depth of approximately 4 m. Fouling organisms were brushed from the culture apparatus during the course of the experiment at monthly intervals and the experiment was

Ž .

3. Results

Ž .

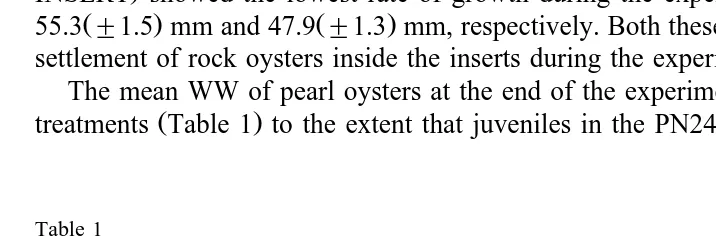

Survival during the experiment was high and ranged from 100% to 90.6% Table 1 .

Ž .

Lowest survival during the experiment was recorded in the INSERT treatment 90.6% whilst the EAR treatment recorded 93.7% survival. Survival in the TRAY treatment was 98.9% and no mortalities were recorded in the PN24 and PN8 treatments.

Mean DVH and WW of P. margaritifera juveniles at the end of the experiment are

Ž .

shown in Table 1. The largest juveniles, with a mean DVH of 65.8"1.0 mm, were

Ž .

recorded in the PN24 treatment; however, there was no significant difference P)0.05

between these juveniles and those in the EAR treatment, which had a mean DVH of

Ž .

64.1"0.8 mm. Juveniles in the PN24 and EAR treatments had significantly greater

Ž .

DVH P-0.05 than oysters in all other treatments. It is notable that oysters in the

PN24 and EAR treatments also had narrower size ranges than those in the other three

Ž

treatments. Pearl oysters held in inserts both within adult panel nets and alone PN8 and

.

INSERT showed the lowest rate of growth during the experiment with mean DVH of

Ž . Ž .

55.3"1.5 mm and 47.9"1.3 mm, respectively. Both these treatments suffered heavy settlement of rock oysters inside the inserts during the experiment.

The mean WW of pearl oysters at the end of the experiment varied notably between

Ž .

treatments Table 1 to the extent that juveniles in the PN24 and EAR treatments were

Table 1

Ž . Ž .

Survival, mean "SE dorso-ventral shell height DVH and wet weight of P. margaritifera juveniles held for 150 days in five different culture regimes1. Ranges are shown in parentheses and means in columns with

Ž .

the same superscript are not significantly different P )0.05

Ž . Ž . Ž .

Treatment Survival % DVH mm Wet Weight g

a a

INSERT 90.62 47.9 "1.3 12.5 "0.8

Ž32.0–73.0. Ž5.4–28.5.

1 Ž .

more than three times heavier than juveniles from the INSERT treatment. Oysters held in PN24 and EAR treatments had a significantly greater WW than individuals in all

Ž . Ž .

other treatments P-0.05 . The lowest mean wet weight of 12.5"0.8 g was recorded

for pearl oysters grown in inserts.

4. Discussion

There are few published data on the growth rates of P. margaritifera juveniles held

Ž .

under different nursery culture conditions. Alagarswami et al. 1989 held hatchery-re-ared P. margaritifera spat in pearl nets suspended from a raft at a depth of 5 m and

Ž .

reported a daily DVH growth rate of 0.4 mm per day. Coeroli et al. 1984 reported that wild collected P. margaritifera spat held in suspended culture in French Polynesia reached a DVH of 8–10 mm after 3 months and 40–50 mm after 6 months, while

Ž .

Southgate and Beer 1997 report that the largest mean DVH and WW of 7-month-old, hatchery-reared P. margaritifera juveniles in Australia was 40.5 mm and 7.4 g,

Ž .

respectively. In the Solomon Islands, Friedman and Southgate 1999 reported that juvenile P. margaritifera with initial DVH of 18.3–51.5 mm increased in size by 20.4–24.8 mm in 3 months and by 30.7–36.5 mm in 5 months.

Pearl oysters held within inserts, either alone or within adult panel nets, showed the poorest growth rates during this experiment. This most likely resulted from biofouling associated with the mesh. Heavy settlement of rock oysters, Crassostrea spp., was evident in both treatments. It is likely that the small mesh size of the plastic inserts used

Ž .

in this experiment 5 mm provided a suitable substrate for rock oyster settlement. Rock oyster settlement within the inserts no doubt increased competition for food and space and reduced the flow of water to the pearl oysters. Crassostrea spp. have previously been reported to be a major fouling species of Pinctada maxima during nursery culture

Ž . Ž

in Indonesia Taylor et al., 1997b and Pinctada fucata in India Alagarswami and

.

Chellam, 1976 . Fouling is a significant problem in pearl oyster culture, leading to poor

Ž . Ž

growth, shell deformation Taylor et al., 1997b , decrease in shell quality Doroudi,

. Ž .

1996 and mortality Alagarswami and Chellam, 1976; Mohammad, 1976 . It has been estimated that up to 30% of the operational expenses of bivalve farming are devoted to

Ž .

cleaning Claereboudt et al., 1994 .

Maximising growth rates of pearl oysters reduces the time required for them to reach operable size for pearl production. An important point to note in the results of this study is the narrower size range of pearl oysters in the PN24 and ear-hung treatments. This is significant because a narrower size range will result in a greater proportion of a given cohort of pearl oysters reaching operable size in a given time, thereby maximising financial return. The larger size ranges shown by oysters in other treatments probably result from their aggregation, a problem previously identified in pearl oyster nursery

Ž .

culture Crossland, 1957; Southgate and Beer, 1997; Taylor et al., 1997a . The gregari-ous nature of pearl oyster juveniles inevitably leads to ‘clumping’ where individuals in

Ž

the centre of ‘clumps’ show reduced growth rates and shell deformity Southgate and

.

with an initial mean DVH of 9.8–13.9 mm held for 19 weeks in trays and pearl nets,

ŽSouthgate and Beer, 1997 . Mortality of 6–12-month-old P. margaritifera juveniles in.

Ž .

French Polynesia has been reported at approximately 30% Coeroli et al., 1984 . In the Solomon Islands, mean survival of 86.9% was reported for P. margaritifera juveniles

Ž24–33 mm DVH reared in lantern nets and panel nets for 3 months Friedman and. Ž

.

Southgate, 1999 .

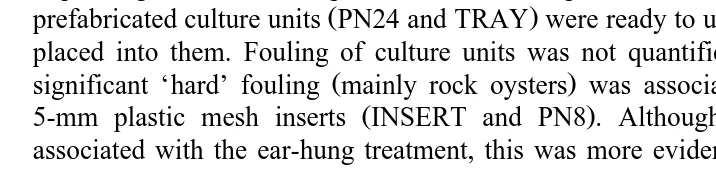

The method selected for nursery culture of bivalves must account for local

condi-Ž .

tions, differences between culture species Gaytan-Mondragon et al., 1993 , and

eco-Ž . Ž .

nomic Rahma and Newkirk, 1987 and practical considerations Crawford et al., 1988 . Using a number of criteria, including cost of equipment, ease of construction and degree of fouling, as well as growth and survival, each of the five nursery culture methods assessed in this study are ranked in Table 2. Under the conditions in this study, the five

Ž .

nursery methods were given an overall ranking in descending order of PN24)EAR)

Ž .

TRAY)PN8)INSERT Table 2 . The lowest equipment cost was associated with

Ž .

ear-hanging, while prefabricated culture units panel nets and trays generally cost

Ž . Ž .

between US$7 PN24 and US$9 TRAY . Although relatively cheap, ear-hanging requires greater labour input in terms of chaplet construction. In contrast, the best

Ž .

prefabricated culture units PN24 and TRAY were ready to use and oysters were simply placed into them. Fouling of culture units was not quantified in this study; however,

Ž .

significant ‘hard’ fouling mainly rock oysters was associated with treatments using

Ž .

5-mm plastic mesh inserts INSERT and PN8 . Although there was algal fouling

associated with the ear-hung treatment, this was more evident in the PN24 and TRAY

Table 2

(

Criteria used to assess the relative merits of five methods of nursery culture for juvenile pearl oysters P.

)

margaritifera . 1sleast favourable, 5smost favourable.

treatments where, presumably, the mesh associated with both culture units provided a more suitable substrate for algae. Selection of appropriate nursery culture methods must

Ž .

consider factors other than pure biological advantage i.e. growth and survival . Further-more, it should be noted that the criteria used to assess the suitability of a given culture unit may vary between sites depending on local conditions such as predator composition and abundance, and the degree of fouling. Predation is not a major cause of juvenile

Ž .

pearl oyster mortality at Orpheus Island Southgate and Beer, 1997 ; however, in areas like the Solomon Islands where predation results in significant pearl oyster mortality

ŽFriedman and Bell, 1996 , nursery culture units should be selected with a view to.

Ž .

minimising predation Friedman and Southgate, 1999 . Clearly, in developing countries or remote locations, the choice of nursery culture unit will also be influenced by what is locally available.

Acknowledgements

This study was conducted at James Cook University’s Orpheus Island Research

Ž .

Station OIRS . We thank the staff of OIRS and a number of volunteers who assisted

with the study. The study was conducted as part of project FISr97r31 ‘Pearl Oyster

Resource Development in the Pacific Island’ funded by the Australian Centre for

Ž .

International Agricultural Research ACIAR . Panel nets used in this study were

provided by Australian Netmakers, Perth, Western Australia.

References

Alagarswami, K., Chellam, A., 1976. On fouling and boring organisms and mortality of pearl oysters in the farm at Veppalodai, Gulf of Mannar. Indian J. Fish. 23, 10–22.

Alagarswami, K., Dharmaraj, S., Chellam, A., Velayudhan, T.S., 1989. Larval and juvenile rearing of the

Ž .

black-lip pearl oyster, Pinctada margaritifera L. . Aquaculture 76, 43–56.

Ž .

AQUACOP, 1982. French Polynesia-Country report. In: Davy, F.B., Graham, M. Eds. , Bivalve Culture in Asia and the Pacific. Proceedings from a workshop 16–19 February 1982, Singapore. International Development Research Centre, Ottawa, pp. 31–33.

Claereboudt, M.R., Bureau, D., Cote, J., Himmelman, J.H., 1994. Fouling development and its effects on the

Ž .

growth of juvenile giant scallops Placopecten magellanicus in suspended culture. Aquaculture 121,

327–342.

Clarke, R.P., Sarver, D.J., Sims, N.A., 1996. Some history, recent developments and prospects for the blacklip pearl oyster, Pinctada margaritifera in Hawaii and Micronesia. Information Paper No. 36. 26th Regional Technical Meeting on Fisheries, Noumea, New Caledonia, 5–9 August 1996. South Pacific Commission. Coeroli, M., De Gaillande, D., Landret, J.P., Coatanea, D., 1984. Recent innovations in cultivation of molluscs

in French Polynesia. Aquaculture 39, 45–67.

Crawford, C.M., Lucas, J.S., Nash, W.J., 1988. Growth and survival during the ocean-nursery rearing of giant clams, Tridacna gigas: 1. Assessment of four culture methods. Aquaculture 68, 103–113.

Crossland, C., 1957. The cultivation of mother of pearl oyster in the Red Sea. Aust. J. Mar. Freshwater Res. 8, 111–130.

Mohammad, M.B.M., 1976. Relationship between biofouling and growth of the pearl oyster Pinctada fucata

ŽGould in Kuwait, Arabian Gulf. Hydrobiologia 51, 129–138..

Preston, G., 1990. Pearl oyster culture in three French Polynesian atolls, 1986–1987. SPC Pearl Oyster Information Bulletin 1, 10–12.

Rahma, I.H., Newkirk, G.F., 1987. Economics of tray culture of the mother-of-pearl shell Pinctada

Ž .

margaritifera in the Red Sea, Sudan. J. World Aquacult. Soc. 18 3 , 156.

Remoissenet, G., 1996. From the emergence of mortalities and diseases on Pinctada margaritifera to their effects on the pearling industry. In: Present and Future of Aquaculture Research and Development in the Pacific Island Countries. Proceedings of the international workshop held from 20 November to 24 November 1995 at Ministry of Fisheries, Tonga. JICA. pp. 371–386.

Ž .

Sims, N.A., 1993. Pearl Oysters. In: Wright, A., Hill, L. Eds. , Nearshore Marine Resources of the South Pacific. FFArICOD, pp. 409–430.

Ž

Southgate, P.C., Beer, A.C., 1997. Hatchery and early nursery culture of the blacklip pearl oyster Pinctada

. Ž .

margaritifera, L. . J. Shellfish Res. 16 2 , 561–567.

Taylor, J.J., Rose, R.A., Southgate, P.C., Taylor, C.E., 1997a. Effects of stocking density on growth and

Ž .

survival of early juvenile silverlip pearl oysters, Pinctada maxima Jameson , held in suspended nursery culture. Aquaculture 153, 41–49.

Taylor, J.J., Southgate, P.C., Rose, R.A., 1997b. Fouling animals and their effect on the growth of silver-lip

Ž .