Search Strategies for a Christmas Gift

Michel Laroche

CONCORDIAUNIVERSITYGad Saad

CONCORDIAUNIVERSITY

Chankon Kim

SAINTMARY’SUNIVERSITYElizabeth Browne

CONCORDIAUNIVERSITYThis study investigates usage of in-store information sources by Anglo as a notable social mechanism. Otnes (1990) argued that four

and Franco-Canadians while Christmas shopping. A literature review characteristics distinguish Christmas from other annual

gift-revealed a number of situational, personal, and demographic variables giving occasions including: (1) the highest level of cultural

that may influence search behavior for a Christmas gift. A survey was recognition of all gift-giving occasions featuring more than

conducted soon after the Christmas season to explore the effects of the one giver and receiver; (2) more media attention than other

identified moderators on the extent of search as pertaining to a clothing annual gift occasions; (3) more marketing effort than other

gift. Three dimensions of in-store search were found: general information gift-giving occasions (e.g., Mother’s Day); (4) immediate

reci-(e.g., displays), specific information reci-(e.g., brand), and assistance of sales- procity is expected (p. 8). Otnes concludes that “this type

clerks. Each of the three search indices was regressed on the identified of exchange could be described as the most sociologically variables. Directional hypotheses were posited linking each of the modera- significant gift giving in modern American culture” (p. 8). tors of search to extent of search. The models faired well both in terms In today’s global economy, understanding cross-cultural of fit and in their rate of support for the hypotheses. Distinct patterns of consumption differences is an imperative strategic tool for in-store search behavior were found for each cultural group, some consis- ensuring long-term viability. While culture is the most general tent with current knowledge, others providing new findings. J BUSN RES and indirect socialization agent, its importance in shaping

2000. 49.113–126. 2000 Elsevier Science Inc. All rights reserved. consumption habits is nonetheless pervasive. Gift giving, while

a universal behavior found in all societies, varies in the manner by which it is implemented across cultures. While several theories have been proposed to explain possible gift-giving

T

he economic importance of the Christmas season to motives, little research has been conducted on the processesboth manufacturers and retailers is well established. involved in selecting a gift and the likely cross-cultural differ-Christmas holiday sales can account for between 30

ences along the latter behavior. In the current work, we investi-and 50% of a retailer’s total yearly sales (Gifts investi-and Decorative

gate such differences as pertaining to information search prior Accessories, 1987; Ryans, 1977; Banks, 1979). Gift purchases

to the purchase of a Christmas gift. Specifically, we isolate have been placed at 10% of all retail purchases in North

the two dominant cultures within the Quebec market, namely America (Belk, 1979; Sherry, McGrath, and Levy, 1993). In

French and English-Canadians, and accordingly attempt to one study by Belk (1979), close to 30% of the reported

gift-gauge whether differences exist in their search behavior. The giving occasions were for Christmas.

research will be limited to in-store information search for a In addition to its economic significance, Christmas gift

Christmas gift of clothing, given that several researchers have giving is important to the North American culture for it serves

found that clothing was the most popular Christmas gift item (Belk, 1979; Caplow, 1982; Jolibert and Fernandez-Moreno, Address correspondence to Michel Laroche, Department of Marketing, Fac- 1983). In summary, we investigate the relevant situational, ulty of Commerce and Administration, 1455 de Maisonneuve West,

Mont-real, QC H3G 1M8, Canada. personal, and demographic traits that have an effect on

con-Journal of Business Research 49, 113–126 (2000)

2000 Elsevier Science Inc. All rights reserved. ISSN 0148-2963/00/$–see front matter

sumers’ external information search strategies while Christmas and McGrath (1989) investigated merchandise display and store layout. It was determined that the location of the mer-gift shopping and whether these are moderated by one’s

be-longing to the French or English-Canadian culture. chandise within the store had an effect on how well it sold.

Mattson (1982) found that a broad product selection was crucial to gift shoppers, especially when choosing a second

Literature Review

store to visit.Another crucial in-store information source, especially in Human behavior can be dichotomized into those sets of

behav-the context of a gift selection, is behav-the salesclerk. For example, iors that are culturally invariant and those that have been

suggestions offered by a salesclerk can help reduce the per-shaped by one’s context and culture. The former, that is,

ceived risk for the giver. Using personal interviews with both universal behaviors, are determined by evolutionary forces

customers and salespeople, Sherry and McGrath (1989) con-and hence are free of cultural influences. For example, recent

cluded that, while salespeople were potentially informative, work in evolutionary psychology has shown that the traits

they were not always accessed by the customers. In an earlier that men and women seek in potential mates is culturally

study, Ryans (1977) found that in comparing in-home gifts invariant (cf., Buss, 1989, 1994; Buss and Schmitt, 1993).

(gifts for people living with the respondent) to personal use While evolutionary psychology is gaining prominence as a

purchases, respondents relied more heavily on in-store infor-field of inquiry, it nonetheless lags far behind cross-cultural

mation sources. However, the results for out-home gifts were psychology, namely the subbranch that seeks to understand

not significant. Finally, Otnes (1990) uncovered three clusters culturally bound behaviors. Social scientists have identified

of searchers in her study of Christmas shopping, of which the an impressive array of behaviors that are moderated by culture

“eclectic” searchers made greatest use of in-store information (see Berry, Poortinga, Segall, and Dasen [1992] for a thorough

sources. review). Within the marketing realm, there has been a growing

Scholars have identified a slew of variables that moderate trend towards identifying specific consumer-related behaviors

the extent of prepurchase search. These are typically broken (e.g., “patriotic” purchasing) that are highly prone to cultural

down into situational, personal, and demographic variables. influences (cf., Clark, 1990; Manrai and Manrai, 1996). Gift

A brief overview is provided below of each of the three sets giving is one such behavior to which we turn next.

of factors.

Gift Giving

Situational Variables

Several consumer researchers have proposed conceptual

mod-els of the gift-giving process including those by Belk (1976, Given the inherent situational nature of the Christmas gift-1979), Banks (gift-1979), and Sherry (1983). Typically, the pro- giving season, it is not surprising that scholars have identified cess is broken up into a set of distinct stages including the several situational variables including dimensions of perceived prepurchase search for the gift, its exchange with the recipient, risk (e.g., financial, social), predetermined gift selection ideas, and its subsequent consumption. Of most relevance to the the giver-recipient relationship, the difficulty of the gift recipi-current work is the prepurchase search, coined the gestation ent, and time pressure. A brief overview of each variable is

and purchase stage in Sherry’s (Sherry, 1983) and Banks’ provided below.

(Banks, 1979) models, respectively. Within the Christmas gift- The perceived risk associated with a gift purchase can be

giving context, Otnes (1990) and Laroche, Kim, Saad, and of many types, two of the most prevalent being social and

Browne (1997) investigated a myriad of situational, personal- financial risk. In the former case, one might be worried about ity, and demographic variables affecting prepurchase gift offending the recipient if the purchased gift is inappropriate

search. Smith and Beatty (1985) and Sprott and Miyazaki (e.g., buying the wrong bottle of wine for your employer’s

(1995) also have investigated factors moderating the extent dinner). On the other hand, financial risk typically involves of gift search. Given both its theoretical importance to the determining the appropriate budget for the gift. Two risk-information search literature and its practical implications to reduction strategies for reducing social risk include shopping retailers, it is surprising how little research has been conducted with a trusted companion (cf., Grønhaug, 1972; Sherry and

in this area. McGrath, 1989) and obtaining a predetermined list from the

recipient (Otnes, Lowrey, and Kim, 1993). In a retail setting,

In-Store Information Sources

a consumer who is accompanied by a trusted companion might substitute in-store information sources, including sales-While numerous scholars have looked at external search, fewpeople, with the companion’s suggestions. A somewhat differ-have investigated the moderators of search as carried out

ent type of risk-reduction strategy is for the consumer to set specifically within a retail store (i.e., in-store information

a larger budget for the gift. For example, Vincent and Zikmund sources and salesclerk help). Store displays and breadth of

(1975) found that respondents bought more expensive items product selection are two important in-store information

when they were intended as a wedding present than when sources that have been examined in conjunction with gift

might be reduced by setting a higher budget, financial risk personality traits or lifestyle characteristics on gift-giving

be-simultaneously increases due to the higher cost. havior is somewhat surprising. In one of the few studies to have

Another factor affecting the perceived risk of a gift purchase addressed this issue, Otnes (1990) uncovered three relevant is the importance of the giver-recipient relationship. Clearly, psychographic variables: (1) attitude toward or love of shop-the more important shop-the relationship is, shop-the greater shop-the conse- ping (in the current context, this can be extended to love of quences of a poor decision will seem. Of the few studies that Christmas shopping), (2) tendency to use gifts for either iden-have investigated time invested for gift shopping (e.g., Ryans, tity formation or social bonding, and (3) attitude toward the 1977; Heeler, Francis, Okechuku, and Reid, 1979), it appears riskiness of gift giving.

that gifts to more distant people involve less effort for the

purchaser, although the evidence is circumstantial. On a re-

Demographic Variables

lated note, Sprott and Miyazaki (1995) found that the difficulty

The relationship between demographic variables and search of a gift recipient affected the extent of search, such that more

behavior has been addressed by several researchers. In Schan-difficult recipients required greater amounts of gift search.

inger and Sciglimpaglia’s (Schaninger and Sciglimpaglia, As previously mentioned, many consumers will typically

1981) study, age was negatively related to the extent of search. have an a priori gift idea prior to entering a store. This was

Additionally, younger and more educated housewives who confirmed by Banks (1979) wherein it was reported that most

were earlier in the family life cycle and of higher social class gift purchases were planned prior to shopping in the store.

examined more information. Recall that in her study, Otnes Furthermore, in many instances, search was extremely limited

(1990) uncovered three clusters of information searchers. The in that gifts were purchased after visiting only one store. Thus,

respondent’s family size, age, and education level were found in such a situation, it is essential that brand selection for the

to be significant discriminators of the three clusters. Inciden-product class be sufficient, and additionally that in-store

infor-tally, her results contradicted those of Schaninger and Sciglim-mation be adequate enough to distinguish the brands. Thus,

paglia vis-a`-vis the effects of age on the extent of search. while having a greater brand selection offering in a given store

While demographic variables, such as age, have yielded reduces interstore search (i.e., fewer stores might be visited),

mixed results, one of the most robust findings is the differential it is likely to increase the search within that particular store.

effect of gender on the gift-giving ritual. Overwhelmingly, it Finally, of all of the situational variables relevant to the

has been shown that women are much more involved in current discussion, none is as pervasive as the time pressure

Christmas gift shopping (Caplow, 1982; Cheal, 1987; Sherry that most Christmas shoppers typically experience. Given most

and McGrath, 1989; Fischer and Arnold, 1990; Rucker et al., humans’ tendency to procrastinate, it is not surprising that

1991). Of interest to the present study are gender differences much of Christmas shopping is conducted under considerable

specifically pertaining to the use of in-store information sources time duress. This ordinarily affects not only the extent of

while gift shopping, a topic that has been addressed rarely in search but also the choice of information sources (e.g., internal

the literature. memory, friends, in-store sources). The general finding has

been that an increase in time pressure yields a decrease in

The Case for Including Cultural Variables

information search (cf., Beatty and Smith, 1987; Sprott and

Miyazaki, 1995). As previously mentioned, gift giving appears in all societies

even though the rituals and practices vary across cultures. The

Personal Variables

motivations for providing a gift are context dependent, and they include altruism, economic concerns, obligation, social Much of the research that has looked at the effects ofpersonal-exchange, and communication (cf., Wolfinbarger, 1990). Triv-ity traits and/or lifestyle characteristics on search behavior was

ers (1971) argued that reciprocal altruism (a combination of not conducted in the specific context of gift giving. In one of

obligation and altruism) is an evolved trait that is found in the earliest such studies, Rogers (1962) found that innovators

all cultures. In the current context of the Christmas gift-giving engage in greater information search, including in-store sources.

ritual, the predominant motivation is a sense of obligation and/ More recently, Horton (1979) and Locander and Hermann

or adherence to a cultural norm. Goodwin, Smith, and Spiggle (1979) have demonstrated that consumers who view themselves

(1990) defined two types of obligations, namely, reciprocity as bargain hunters conduct more in-store search. On the other

and ritual, both being integral to the Christmas gift-giving ritual. hand, those who were not brand loyal and were more favorable

Much of the research on gift giving stems from the anthro-towards generic products engage in a lesser search of in-store

pological tradition whereby the focus has been on investigating information. Finally, Schaninger and Sciglimpaglia (1981)

in-such behavior within the context of tribal and primitive socie-vestigated the relationship between cognitive personality traits

ties. As such, while anthropologists have looked at gift-giving and information acquisition. They concluded that individuals

practices of numerous cultures, few if any have attempted to having higher self-esteem examined a greater amount of

infor-specifically investigate cross-cultural differences along that mation prior to making a final choice.

appears to be a dearth of relevant research, as evidenced by that there exists significant consumption differences between

the ensuing quotes: the members of the two cultures. Tamilia (1978) found that

in an advertising context, Francophones react more to the No one seems to have conducted cross-cultural studies of

source of the ad (e.g., celebrity endorser) whereas An-this phenomenon (Jolibert and Fernandez-Moreno, 1983,

glophones are more reactive to a message’s content. Addition-p. 191).

ally, Francophones are more introspective, emotional, and The absence of any comparative or cross-national study of humanistic and less pragmatic and materialistic than their

gift giving is part of a more wide-spread circumstance Anglophone counterparts (He´on, 1990). The former tend to

(Jolibert and Fernandez-Moreno, 1983, p. 192). associate price with value, are more willing to pay higher

prices for convenience and premium brands, and are more The study of gift giving cross-culturally is still in its infancy

brand loyal (Vary, 1992). Greater brand loyalty might typically . . ., but offers rich avenues of additional inquiry (Beatty,

lead to reduced information search prior to a purchase, a Kahle, and Homer, 1991, p. 150).

result confirmed by Muller and Bolger (1985) in the context

Jolibert and Fernandez-Moreno (1983) compared French and of a car purchase. Hui, Joy, Kim, and Laroche (1993) found

Mexican Christmas gift-giving practices. The authors conclude that, among other things, Anglophones were less concerned that the most challenging endeavor in this area of inquiry is for children, were less innovative, had less opinion leadership, to identify the specific cultural traits and traditions that gener- and were less fashion conscious. On the other hand, they ate such cross-cultural differences (p. 196). Several researchers demonstrated greater price consciousness, had a higher liking have accordingly pursued such a strategy. Belk (1984) argued

for use of credit, and displayed greater brand loyalty (contra-that gift giving would vary across cultures based on the manner

dicting earlier work, e.g., Mallen, 1977).

by which an individual’s self-concept was defined. Green and Scholars have attempted to understand the factors that

Alden (1988) compared American and Japanese gift-giving prac- might explicate the consumption differences between the tices and found considerable differences across all stages of the members of the two cultures. Early work by Lefranc¸ois and process. The differential need for group affiliation between the Chatel (1967) proposed that such differences were due to two cultures was one of the traits used to explain the obtained socioeconomic factors, namely, that the traditionally lower results. Beatty, Kahle, and Homer (1991) investigated the socioeconomic status of the Francophones translated into cor-frequency of gift giving and the exertion of effort in selecting responding consumption differences. However, several re-a gift in the Americre-an re-and the Fre-ar Ere-ast cultures. The re-authors searchers have since disproved the socioeconomic hypothesis found that, irrespective of culture, personal values (e.g., warm (Palda, 1967; Thomas, 1975; Schaninger, Bourgeois, and Buss, relationships with others versus fun and excitement in life) 1985; Chebat, Laroche, and Malette, 1988; Joy, Kim, and were a good predictor of the latter two gift-giving behaviors.

Laroche, 1991). He´nault (1971) argued that there exist eight In summary, while there does appear to be an increased

cultural traits by which the two cultures differ. Of the most interest in the separate areas of prepurchase gift search and relevant to the current work are that the French are more cross-cultural differences in gift giving, little work has investi- individualistic, less conformist, less pragmatic, have a higher gated the overlapping of the two fields, namely cross-cultural propensity to spend, and are more likely to be financed as differences in the prepurchase gift search. The current work opposed to being the financer. Mallen (1977) proposed that attempts to address this paucity, by specifically looking at the consumption differences were due to three general differ-French and English Canadian differences in terms of the latter ences in traits: (1) the “sensate” trait involving the five senses, behavior. Prior to positing the hypotheses and research objec- namely the French are more likely to react to appeals involving tives, we provide a brief overview of the literature that has the senses; (2) the “conservative” trait that relates to low risk-addressed Franco and Anglo-Canadian differences in several taking behavior and strong family orientation, for example, consumer-related domains.

being more risk-averse; and (3) the “nonprice cognitive” trait, which is an outcome of the other two traits. In other words,

French–English Canadian

if the French like a product due to some sensate trait, they willConsumption Differences

repurchase it irrespective of its price (within some acceptable range of prices). Bouchard (1983) proposed that the French Of the 7.3 million people in Quebec (1995 census estimate),have six common specific cultural and historical roots that the two dominant cultures are the French and English

Cana-translate into 36 responsive chords (i.e., six chords per root). dian ones comprising 80 and 6.3% of the population,

respec-Of most relevance to the current article are the following seven tively. Thus, in addition to its theoretical importance,

under-chords: shrewdness, superconsumerism, eccentric taste, herd standing Franco-Anglo consumption differences has clear

mentality, conservatism, joie de vivre, and individualism. pragmatic implications.

Clearly, the French and English Canadians possess different Differences between French and English-Canadian

con-cultural traits, customs, and traditions subsequently yielding sumers arise for more reasons than solely linguistic ones

concern is the identification of those cultural traits that should ory. The data came from a sample of residents of a major metropolitan area, by using the area sampling method. The moderate prepurchase gift search. For example, given that the

French have a stronger religious background, they might place data collection was confined to a selected number of census tracts in the residential areas of the city. Interviewers ap-greater importance on the Christmas season. Accordingly, this

would increase their task involvement when purchasing a proached households on randomly selected streets in the cho-sen census tracts, and a questionnaire was left with the con-Christmas gift. Similarly, given the nonprice cognitive trait of

the French, price-related factors might be less relevant when senting respondent to be completed and mailed back (postage-paid) at his or her convenience. An additional procedure also shopping for a gift.

was employed by randomly approaching individuals in the hallways of a large shopping mall and leaving with the

con-Objectives of the Current Research

senting respondent a questionnaire to be mailed at his/herconvenience. The study has three key objectives. First, it will gauge whether

Equal numbers of English and French respondents were the extent of search conducted prior to a gift purchase is

sought. Self-identification was used to categorize the respon-moderated by culture. Several cross-cultural psychologists

dents into the two groups. A total of 1,026 questionnaires have proposed that a key cultural value is the “reflective versus

were distributed using the procedures described above, 493 action-oriented” continuum. Clearly, this trait might have an

in English and 533 in French. It was deemed that this number effect on the amount of deliberation that members of a

particu-would yield a sufficient response. A total of 368 usable ques-lar culture engage in prior to committing to a final decision.

tionnaires were returned, yielding an overall return rate of For example, Punnett (1995) compared Chinese and

Ameri-36%. Of these, 155 were from English respondents and 213 can college students along several key cultural dimensions

from French respondents, a response rate of 31 and 40%, including “impulsivity”, a trait that is likely related to the

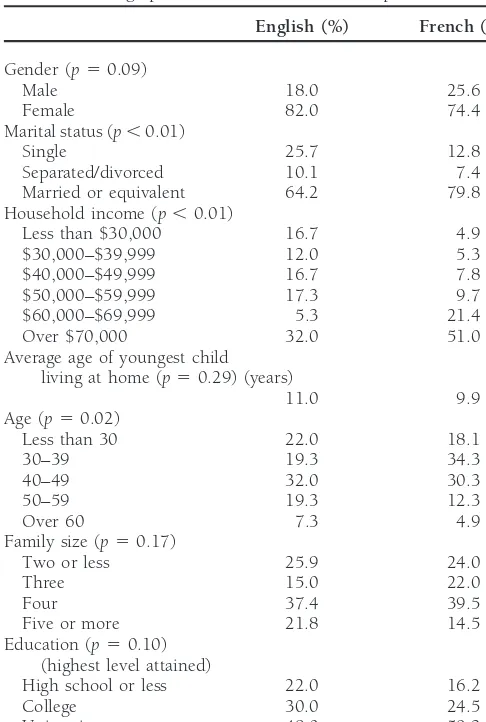

respectively. As can be seen in Table 1, the majority of respon-above continuum. Positing an a priori hypothesis in the

cur-dents are female and are married or its equivalent, and they rent context is very difficult given that many of the cultural

tend to possess above average education and family income. differences between the two cultures would yield

contradic-tory predictions regarding the extent of search. For example,

Questionnaire

the greater brand loyalty typically exhibited by the French

would imply a decrease in search while their Catholic root The questionnaire was divided into three parts: situational, might yield greater task involvement in the Christmas gift- personal, and demographic variables. Only the variables perti-giving ritual thus resulting in an increase in search. nent to the present analysis will be discussed here.

The second objective of the study is to develop comprehen- Part I of the questionnaire contained several questions using sive models of the gift-giving search process for each of the a 10-point Likert scale anchored at 1 5 strongly disagree two cultures and subsequently to explore whether significant and 10 5 strongly agree, designed to measure consumers’ cross-cultural differences exist in the results obtained. A myr- purchase of a specific Christmas gift, as well as their use of in-iad of moderators of search (situational, personal, and demo- store information sources for the same purchase. Respondents graphic variables) will be integrated into general regression were requested to think of a particular gift of clothing that

models. With the exception of Laroche, Kim, Saad, and they had actually purchased for Christmas. As previously

men-Browne (1997), no other study has attempted to include such tioned, clothing was selected because a review of the literature a large set of variables within one model of search. As such, indicated that clothing was the most popular type of gift the theoretical implications of the endeavor appear fruitful. purchased, particularly at Christmas (Belk, 1979; Caplow, Thirdly, we wish to test directional hypotheses between the 1982). First, 33 questions measured purchase-specific situa-moderators of search and the extent of search. For example, tional variables identified in the literature review (see Table one might posit a positive relationship between the cost a gift 2), while 10 questions measured actual in-store information and the extent of search. Accordingly, should the regression search conducted by the respondent for the specific Christmas model yield a significant coefficient for the latter moderator gift purchase (the dependent variables, see Table 3). Part I (i.e., cost of gift), the expectation would be that its sign should also contained one question as to for whom the gift was be positive. This exercise would allow us to fully gauge the intended (coded as 1 5 primary relation, e.g., father; 2 5

explanatory power of the models. secondary relation, e.g., sister or aunt; 35tertiary relation,

e.g., cousin; 45nonrelation), and one question measuring availability of information in the store (“Everything I needed

Research Methodology

to know about the clothing item was available in the store”).

Survey Administration

Part II contained 56 questions designed to measure the personal characteristics of the respondents, by using a 10-In terms of timing, the survey was conducted soon after thepoint Likert-type scale anchored at 15strongly disagree and Christmas season was over, to ensure that the clothing gift

Table 1. Demographic Characteristics of the Sample to see if the strength of religious beliefs is a motivating factor in in-store information search. The last part of the questionnaire

English (%) French (%)

included standard questions about the respondent’s gender,

Gender (p50.09) age, marital status, household income, family size, age of the

Male 18.0 25.6 youngest child at home, and education, among others. The

Female 82.0 74.4 questionnaire was first written in English, then translated into

Marital status (p,0.01)

French, except for the questions taken from Kim, Laroche,

Single 25.7 12.8

and Lee (1989) and Hui, Joy, Kim, and Laroche (1993), which

Separated/divorced 10.1 7.4

Married or equivalent 64.2 79.8 were already available in French. The translation was verified

Household income (p,0.01) by two French-speaking people.

Less than $30,000 16.7 4.9

$30,000–$39,999 12.0 5.3

Data Preparation

$40,000–$49,999 16.7 7.8

$50,000–$59,999 17.3 9.7 The hypothesized relationships between usage of store

in-$60,000–$69,999 5.3 21.4 formation sources and the situational, personal, and

demo-Over $70,000 32.0 51.0

graphic variables were examined using multiple regression Average age of youngest child

analyses. However, prior to running the regression analyses, living at home (p50.29) (years)

some of the data was factor analyzed to develop measures of

11.0 9.9

Age (p50.02) the various constructs, test their reliability, and recode them.

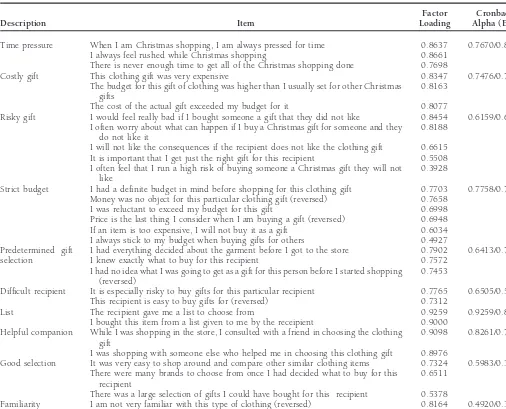

Less than 30 22.0 18.1 From Part I, all of the situational questions together with

30–39 19.3 34.3

the three questions relating to time pressure also were factor

40–49 32.0 30.3

analyzed using Varimax rotation. The solution produced 10

50–59 19.3 12.3

factors explaining 64.0% of the variance, the first eight

exhib-Over 60 7.3 4.9

Family size (p50.17) iting good reliabilities, and the last two marginal reliabilities,

Two or less 25.9 24.0 especially for the French subsample. Table 2 presents the

Three 15.0 22.0

factor loadings and Cronbach’s alphas. While not shown in

Four 37.4 39.5

Table 2, recall that Part I contained two additional constructs

Five or more 21.8 14.5

(“availability of information” and “close relationship”), which Education (p50.10)

(highest level attained) were each measured by a single item.

High school or less 22.0 16.2 Second, the 10 questions in Part I pertaining to in-store

College 30.0 24.5

information search effort were factor analyzed using Varimax

University 48.0 59.3

rotation. The solution produced three factors explaining 67.7% of the variance: in-store search for general information, in-store search for specific information, and information ac-cessed from a salesclerk. The first two constructs involved of an individual’s tastes, preferences, or attitudes that could

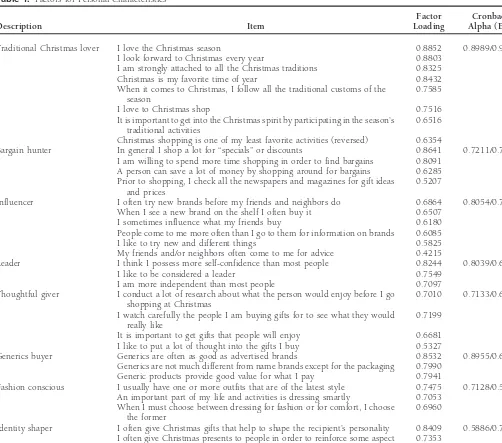

information search that can be conducted alone by the giver, be related to that person’s Christmas shopping behavior (see

with no interaction with other people, whereas the third factor Table 4). Most of these questions were adapted from the

requires personal interaction with the salesclerks. Table 3 lifestyle instrument used by Wells and Tigert (1971). Other

presents the factor loadings and Cronbach’s alphas. questions relating specifically to Christmas or gift shopping

Finally, from Part II of the questionnaire, all the questions and attitude toward time pressure were either developed anew

measuring personal characteristics were factor analyzed using or adapted from the instrument used by Otnes (1990).

Varimax rotation. The solution produced eight factors all ex-Part III of the questionnaire contained a number of

ques-hibiting good reliabilities, and collectively they explained tions related to culture. The first set of questions involved

62.1% of the variance. Table 4 presents the factor loadings evaluating the usage frequency of English and French across

11 activities. These have been shown by Kim, Laroche, and and the Cronbach’s alphas.

A reliability analysis was also performed on the culture-Lee (1989) to be a reliable single measure of acculturation.

Four questions were used to measure identification (I consider related measures. The 12 items measuring acculturation had Cronbach’s alphas of 0.80 and 0.89 for the English and French myself to be English/French Canadian …; My parents are

English/French Canadians …). Three questions were related samples. The four items measuring identity had Cronbach’s

alphas of 0.69 and 0.62, respectively. The three items measur-to religion: I consider myself measur-to be a strong Protestant/Catholic

believer, I had a strong Protestant/Catholic childhood up- ing religious beliefs and upbringing had Cronbach’s alphas of 0.93 and 0.89. Religious beliefs and religious upbringing were bringing, Protestant/Catholic beliefs are an important part of

my life. All these questions were on a 10-point Likert-type related to the religion (Protestant or Catholic) declared by the respondent. For the multiple regression analyses, the mean scale anchored at 15strongly disagree, 105strongly agree.

Table 2. Factors for Situational Variables

Factor Cronbach

Description Item Loading Alpha (E/F)

Time pressure When I am Christmas shopping, I am always pressed for time 0.8637 0.7670/0.8354

I always feel rushed while Christmas shopping 0.8661

There is never enough time to get all of the Christmas shopping done 0.7698

Costly gift This clothing gift was very expensive 0.8347 0.7476/0.7902

The budget for this gift of clothing was higher than I usually set for other Christmas 0.8163 gifts

The cost of the actual gift exceeded my budget for it 0.8077

Risky gift I would feel really bad if I bought someone a gift that they did not like 0.8454 0.6159/0.6222 I often worry about what can happen if I buy a Christmas gift for someone and they 0.8188

do not like it

I will not like the consequences if the recipient does not like the clothing gift 0.6615 It is important that I get just the right gift for this recipient 0.5508 I often feel that I run a high risk of buying someone a Christmas gift they will not 0.3928

like

Strict budget I had a definite budget in mind before shopping for this clothing gift 0.7703 0.7758/0.7714 Money was no object for this particular clothing gift (reversed) 0.7658

I was reluctant to exceed my budget for this gift 0.6998

Price is the last thing I consider when I am buying a gift (reversed) 0.6948 If an item is too expensive, I will not buy it as a gift 0.6034 I always stick to my budget when buying gifts for others 0.4927

Predetermined gift I had everything decided about the garment before I got to the store 0.7902 0.6413/0.7382

selection I knew exactly what to buy for this recipient 0.7572

I had no idea what I was going to get as a gift for this person before I started shopping 0.7453 (reversed)

Difficult recipient It is especially risky to buy gifts for this particular recipient 0.7765 0.6505/0.5639

This recipient is easy to buy gifts for (reversed) 0.7312

List The recipient gave me a list to choose from 0.9259 0.9259/0.8465

I bought this item from a list given to me by the receipient 0.9000

Helpful companion While I was shopping in the store, I consulted with a friend in choosing the clothing 0.9098 0.8261/0.7984 gift

I was shopping with someone else who helped me in choosing this clothing gift 0.8976

Good selection It was very easy to shop around and compare other similar clothing items 0.7324 0.5983/0.3775 There were many brands to choose from once I had decided what to buy for this 0.6511

recipient

There was a large selection of gifts I could have bought for this recipient 0.5378

Familiarity I am not very familiar with this type of clothing (reversed) 0.8164 0.4920/0.3550

I have bought this type of clothing often in the past 0.6182

Table 3. Factors for In-Store Information Search Effort

Factor Cronbach

Description Item Loading Alpha (E/F)

Impersonal sources

General information search I looked at all the items in the display area where I bought the gift 0.8464 0.8335/0.8174 I walked around the store looking at the display of all merchandise 0.8153

I checked all the prices very carefully 0.7305

I spent a lot of time comparing the brands or clothing items in the store 0.6557

I read all the signs around the display area 0.5396

Specific information search I very carefully read the manufacturer’s label 0.8880 0.7453/0.7918 I very carefully examined the packaging information 0.8161

I tried to get as much information as possible in the store about this 0.6198 clothing item

Personal source

Salesclerk help I received a lot of help from the salesclerk 0.8566 0.6805/0.5145

Table 4. Factors for Personal Characteristics

Factor Cronbach

Description Item Loading Alpha (E/F)

Traditional Christmas lover I love the Christmas season 0.8852 0.8989/0.9225

I look forward to Christmas every year 0.8803

I am strongly attached to all the Christmas traditions 0.8325

Christmas is my favorite time of year 0.8432

When it comes to Christmas, I follow all the traditional customs of the 0.7585 season

I love to Christmas shop 0.7516

It is important to get into the Christmas spirit by participating in the season’s 0.6516 traditional activities

Christmas shopping is one of my least favorite activities (reversed) 0.6354

Bargain hunter In general I shop a lot for “specials” or discounts 0.8641 0.7211/0.7056

I am willing to spend more time shopping in order to find bargains 0.8091 A person can save a lot of money by shopping around for bargains 0.6285 Prior to shopping, I check all the newspapers and magazines for gift ideas 0.5207

and prices

Influencer I often try new brands before my friends and neighbors do 0.6864 0.8054/0.7155

When I see a new brand on the shelf I often buy it 0.6507

I sometimes influence what my friends buy 0.6180

People come to me more often than I go to them for information on brands 0.6085

I like to try new and different things 0.5825

My friends and/or neighbors often come to me for advice 0.4215

Leader I think I possess more self-confidence than most people 0.8244 0.8039/0.6985

I like to be considered a leader 0.7549

I am more independent than most people 0.7097

Thoughtful giver I conduct a lot of research about what the person would enjoy before I go 0.7010 0.7133/0.6824 shopping at Christmas

I watch carefully the people I am buying gifts for to see what they would 0.7199 really like

It is important to get gifts that people will enjoy 0.6681 I like to put a lot of thought into the gifts I buy 0.5327

Generics buyer Generics are often as good as advertised brands 0.8532 0.8955/0.6725

Generics are not much different from name brands except for the packaging 0.7990 Generic products provide good value for what I pay 0.7941

Fashion conscious I usually have one or more outfits that are of the latest style 0.7475 0.7128/0.5901 An important part of my life and activities is dressing smartly 0.7053

When I must choose between dressing for fashion or for comfort, I choose 0.6960 the former

Identity shaper I often give Christmas gifts that help to shape the recipient’s personality 0.8409 0.5886/0.7191 I often give Christmas presents to people in order to reinforce some aspect 0.7353

of ther identity

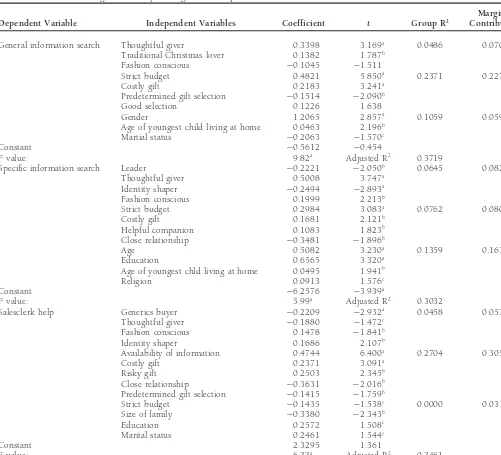

Finally, demographic variables measured on nominal scales regression analyses were run for each dependent variable and were converted to dummy variables (gender: female 5 1, for each subgroup1. The results for each of the three regression

male50); or interval variables (marital status was converted analyses are summarized in Table 5 for the English subgroup to: single, separated/divorced/widow, and married/living to- and in Table 6 for the French subgroup.

gether). In summary, reliable and significant factors were

found for the personal, situational, and culture-related vari-

Objective 1: Is Extent of Search

ables and for in-store information search.

Moderated by Culture?

An ANCOVA analysis (controlling for education, income, gen-der, marital status, age) was conducted for each of the three

Results

search indices to determine whether belonging to a given The data was analyzed for relationships between the three

groups of independent variables (personal, situational, and

demographic) and the three dependent variables related to in- 1Twelve respondents were dropped (five and seven from the English and

French samples, respectively) following an analysis of outliers.

Table 5. Results of the Regression Analyses: English Subsample

Marginal

Dependent Variable Independent Variables Coefficient t Group R2 Contribution

General information search Thoughtful giver 0.3398 3.169a 0.0486 0.0707

Traditional Christmas lover 0.1382 1.787b

Fashion conscious 20.1045 21.511

Strict budget 0.4821 5.850a 0.2371 0.2270

Costly gift 0.2183 3.241a

Predetermined gift selection 20.1514 22.090b

Good selection 0.1226 1.638

Gender 1.2065 2.857a 0.1059 0.0592

Age of youngest child living at home 0.0463 2.196b

Martial status 20.2063 21.570c

Constant 20.5612 20.454

F value: 9.82a Adjusted R2 0.3719

Specific information search Leader 20.2221 22.050b 0.0645 0.0820

Thoughtful giver 0.5008 3.747a

Identity shaper 20.2494 22.893a

Fashion conscious 0.1999 2.213b

Strict budget 0.2984 3.083a 0.0762 0.0808

Costly gift 0.1681 2.121b

Helpful companion 0.1083 1.823b

Close relationship 20.3481 21.896b

Age 0.5082 3.230a 0.1359 0.1630

Education 0.6565 3.320a

Age of youngest chld living at home 0.0495 1.941b

Religion 0.0913 1.576c

Constant 26.2576 23.939a

F value: 5.99a Adjusted R2 0.3032

Salesclerk help Generics buyer 20.2209 22.932a 0.0458 0.0538

Thoughtful giver 20.1880 21.472c

Fashion conscious 0.1478 21.841b

Identity shaper 0.1686 2.107b

Availability of information 0.4744 6.400a 0.2704 0.3054

Costly gift 0.2371 3.091a

Risky gift 0.2503 2.345b

Close relationship 20.3631 22.016b

Predetermined gift selection 20.1415 21.759b

Strict budget 20.1435 21.538c 0.0000 0.0312

Size of family 20.3380 22.343b

Education 0.2572 1.508c

Marital status 0.2461 1.544c

Constant 2.3295 1.361

F value: 6.33a Adjusted R2 0.3461

The Group adjusted R2is obtained when only the group of variables (personal, situational, demographics) is regressed on the dependent variables. The marginal contribution is the

loss of adjusted R2obtained when the group of variables is removed from the regression. aSignificant atp

,0.01 (one-way).

bSignificant atp

,0.05 (one-way).

cSignificant atp

,0.10 (one-way).

culture influenced one’s extent of prepurchase gift search. The which will be impossible to compromise regardless of the extent and length of contact with the majority cultural group. sole significant difference was for general information whereby

the English engaged in greater search (p,0.02). Language(s) used by minority group members, especially in

the choice of mass media such as radio, television, and news-In the multicultural context of the Quebec market where

many cultural groups are in continuous contact with one paper, is one aspect that is partly determined by the length and extent of their contact with the majority group (Kim, another, it is important that cross-cultural studies incorporate

acculturation as a key covariate. The latter refers to the degree Laroche, and Lee, 1989). Identification and language accultur-ation were therefore used in this article to measure culture to which the values and norms of an individual or a cultural

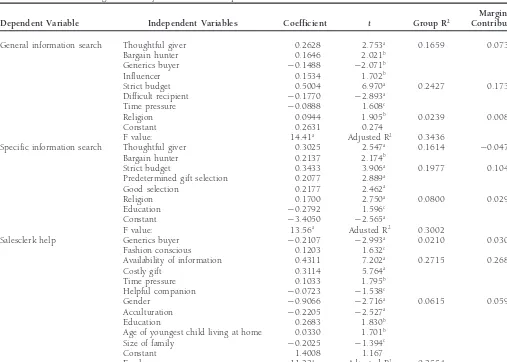

Table 6. Results of the Regression Analyses: French Subsample

Marginal

Dependent Variable Independent Variables Coefficient t Group R2 Contribution

General information search Thoughtful giver 0.2628 2.753a 0.1659 0.0739

Bargain hunter 0.1646 2.021b

Generics buyer 20.1488 22.071b

Influencer 0.1534 1.702b

Strict budget 0.5004 6.970a 0.2427 0.1738

Difficult recipient 20.1770 22.893a

Time pressure 20.0888 1.608c

Religion 0.0944 1.905b 0.0239 0.0087

Constant 0.2631 0.274

F value: 14.41a Adjusted R2 0.3436

Specific information search Thoughtful giver 0.3025 2.547a 0.1614

20.0476

Bargain hunter 0.2137 2.174b

Strict budget 0.3433 3.906a 0.1977 0.1042

Predetermined gift selection 0.2077 2.889a

Good selection 0.2177 2.462a

Religion 0.1700 2.750a 0.0800 0.0299

Education 20.2792 1.596c

Constant 23.4050 22.565a

F value: 13.56a Adusted R2 0.3002

Salesclerk help Generics buyer 20.2107 22.993a 0.0210 0.0307

Fashion conscious 0.1203 1.632c

Availability of information 0.4311 7.202a 0.2715 0.2681

Costly gift 0.3114 5.764a

Time pressure 0.1033 1.795b

Helpful companion 20.0723 21.538c

Gender 20.9066 22.716a 0.0615 0.0592

Acculturation 20.2205 22.527a

Education 0.2683 1.830b

Age of youngest child living at home 0.0330 1.701b

Size of family 20.2025 21.394c

Constant 1.4008 1.167

F value: 11.23a Adjusted R2 0.3554

The group adjusted R2is obtained when only the group of variables (personal, situational, demographics) is regressed on the dependent variables. The marginal contribution is the

loss of adjusted R2obtained when the group of variables is removed from the regression. aSignificant atp

,0.01 (one-way).

bSignificant atp

,0.05 (one-way).

cSignificant atp

,0.10 (one-way).

between the two cultures. Thus, following the temporary re- Looking at the adjusted R2 values allows one to gauge the

data fit to each of the regression models. For the English moval of the highly acculturated individuals from both

sam-ples, the ANCOVA analysis was repeated. In this case, the sample, these were 0.3719, 0.3032, and 0.3461 for general, specific, and salesclerk information, respectively. On the other sole significant difference was for salesclerk help, whereby the

French engaged in greater search (p , 0.01). This accords hand, for the French sample, the corresponding adjusted R2

values were 0.3436, 0.3002, and 0.3554. Thus, it appears with the results of He´on (1990), namely that the French are

more humanistic, which in this case translates into greater that the regression models yielded equally good fits not only when comparing across cultures but also across search indices. human interaction. Table 7 displays the search results for both

sets of samples (i.e., the complete samples and those wherein The last two columns in Tables 5 and 6 report the group

the highly acculturated individuals were removed2). adjusted R2and the marginal contribution scores. The former

is obtained when only the group of variables (personal,

situa-Objective 2: Explore Comprehensive Models

tional, demographics) is regressed on the dependent variables. The marginal contribution is the loss of adjusted R2obtainedof Search and Compare Between the Two Cultures

when the group of variables is removed from the regression. Both Tables 5 and 6 display the results of three regression

Based on the group R2 and marginal contribution scores, it

equations, namely one for each of the three search indices.

appears that the situational variables were the most important ones to both samples, an intuitive result given the inherent

2For this analysis, the removal of the highly acculturated individuals

situational nature of the Christmas gift-giving season.

from both samples yielded 78 “strong” English individuals and 75 “strong”

summa-Table 7. Extent of Search for Each of the Three Search Indices 36 and 26 significant slopes, respectively, suggesting that the former have a more complex search process. The number of

I English French p-value

times that the two cultures yielded a significant slope on the same search index and with the same directionality (i.e., same Complete data set

General information 6.48 5.80 0.012 sign) was 10. On the other hand, on only two occasions did Specific information 4.87 5.38 0.106 the two cultures yield a significant slope for a given search

Salesclerk help 5.09 5.54 0.123

index but with opposite directionality. For the 38 remaining Removal of acculturated

cases (i.e., 622 202 4), there was a significant coefficient respondents from

for only one of the two cultures. Of the latter 38 cases, 14 both groups

General information 630 5.70 0.148 were from the French sample whereas 24 were from the En-Specific information 5.23 5.11 0.803 glish sample. A breakdown of the 38 cases across the three

Salesclerk help 4.69 5.78 0.009

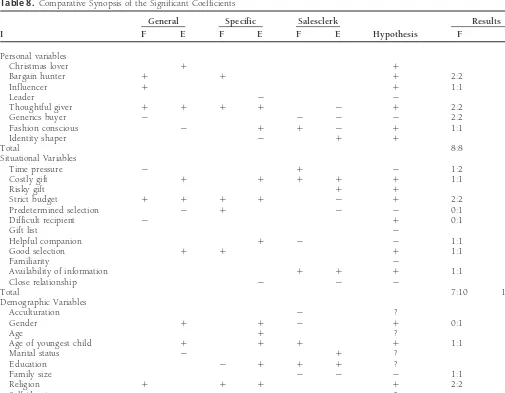

search indices reveals that general, specific, and salesclerk search yielded 14, 12, and 12 cases, respectively. A similar breakdown but along type of variable revealed that personal, rized in a comparative fashion in Table 8. There were 62 situational, and demographic variables had 11, 16, and 11 of significant coefficients (out of a possible 174, i.e., 29 the cases, respectively. Thus, it does not appear that any trends variables33 search indices32 cultures). These were broken- exist regarding the pattern of cross-cultural differences.

up as follows: 19 personal (11 English; 8 French); 24 situa- As previously mentioned, an unexpected result was the

tional (14 English; 10 French); and 19 demographic (11 En- fact that search could be broken-up into three distinct indices. As such, we decided to explore whether a given moderator glish; 8 French). Thus, the English and French samples yielded

Table 8. Comparative Synopsis of the Significant Coefficients

General Specific Salesclerk Results

I F E F E F E Hypothesis F E

Personal variables

Christmas lover 1 1 1:1

Bargain hunter 1 1 1 2:2

Influencer 1 1 1:1

Leader 2 2 1:1

Thoughtful giver 1 1 1 1 2 1 2:2 2:3

Generics buyer 2 2 2 2 2:2 1:1

Fashion conscious 2 1 1 2 1 1:1 1:3

Identity shaper 2 1 1 1:2

Total 8:8 7:11

Situational Variables

Time pressure 2 1 2 1:2

Costly gift 1 1 1 1 1 1:1 3:3

Risky gift 1 1 1:1

Strict budget 1 1 1 1 2 1 2:2 2:3

Predetermined selection 2 1 2 2 0:1 2:2

Difficult recipient 2 1 0:1

Gift list 2

Helpful companion 1 2 2 1:1 0:1

Good selection 1 1 1 1:1 1:1

Familiarity 2

Availability of information 1 1 1 1:1 1:1

Close relationship 2 2 2 2:2

Total 7:10 12:14

Demographic Variables

Acculturation 2 ?

Gender 1 1 2 1 0:1 2:2

Age 1 ?

Age of youngest child 1 1 1 1 1:1 2:2

Marital status 2 1 ?

Education 2 1 1 1 ?

Family size 2 2 2 1:1 1:1

Religion 1 1 1 1 2:2 1:1

Self-identity ?

of search could have a differential effect across two or more moderators had a differential effect on two or more search indices. For example, in the English sample, the personality search indices (i.e., being positively related to one and

nega-tively related to another). For the English sample, there were trait “thoughtful giver” was positively related to both general and specific search and negatively related to salesclerk help. 11 cases (5 sign reversals) whereby a moderator was significant

for two or more search indices whereas for the French sample Had only one aggregate component of search been used in the current study, the regression model might have yielded the number was 7 (2 sign reversals). This tentatively suggests

that in some instances, a given moderator of search will have no relationship between the latter personality trait and extent of search, masking the underlying set of significant effects. a differential effect on two or more search indices. For

exam-ple, time pressure, which solely entered the regression in the Given that much of the existing search literature has precisely used one aggregate component of search, the latter result has French sample, led to less general search and more salesclerk

help. In other words, not only does search become more clear theoretical implications.

The six regression models faired quite well both in terms directed, but also a shift occurs in terms of seeking

informa-tional sources that have lower acquisition costs. In this case, of fit (median adjusted R2

50.3462) and with respect to the posited directional hypotheses (81.5% support rate). Only the differential costs correspond to the difference in time it

takes to seek the information from a salesperson versus looking three of the twenty-nine moderators of search, namely “gift

for general information. list,” “familiarity” (with the product category), and self-identity

did not yield a single significant coefficient, demonstrating that a preponderance of the identified moderators affect search

Objective 3: Test Directional Hypotheses of

behavior. Johnson and Russo (1984) showed that the

relation-Specific Moderators and Extent of Search

ship between extent of search and familiarity with a product The second-to-last column in Table 8 shows the directional

category corresponded to an inverted-U function. In other predictions that were made for 24 out of 29 moderators. No

words, moderately familiar consumers search the most while predictions were made for the following five demographic

novices and experts engage in lesser search, albeit for different variables: acculturation, age, marital status, education, and

reasons. Hence, the null effect that we obtained for “familiar-self-identity. Specifically, we posited a hypothesis to predict,

ity” might have been due to our attempt to fit a linear function ceteris paribus, the effect that an increase in the moderator

to a curvilinear relationship. would have on the extent of prepurchase search. The

predic-Several notable cross-cultural differences were identified. tions were made vis-a`-vis a general component of search since

First, following the temporary removal of the highly accultu-a priori we did not know thaccultu-at we would obtaccultu-ain accultu-a

three-rated individuals from both samples, it was found that the factor solution. The predictions were based on either previous

French make greater use of salesclerk help. No significant findings in the literature and/or a cost/benefit model of search.

differences were obtained either for general or specific infor-For example, as the availability of information increases, its

mation. Across both samples, 62 significant coefficients were acquisition costs decrease, and hence one would expect a

obtained, of which only 20 (i.e., 32%) were “shared” by both corresponding increase in search. Similarly, the more of a

cultures. Hence, it appears that substantial cross-cultural dif-bargain hunter one is, the greater the likely benefits in search

ferences exist in terms of the patterns of significant slopes. for additional information. The last column in Table 8 displays

That being said, an exploratory analysis revealed that neither the number of cases that supported/refuted each of the posited

the type of search index nor the type of moderator could explain hypotheses. For the English sample, 7:11 (personal), 12:14

the pattern of cross-cultural differences. In other words, the (situational), and 6:6 (demographic) supported the posited

cross-cultural differences were evenly distributed across the directional hypotheses. On the other hand, for the French

three search indices and three types of moderators. One pattern sample, the corresponding ratios were 8:8, 7:10, and 4:5.

that did emerge was that the search behavior of the English Thus, in total 25:31 (80.7%) of the directional hypotheses

sample was more complex, as evidenced by the greater number were supported for the English sample whereas, 19:23

of significant coefficients (36 vs. 26 for the French). (82.6%) were supported for the French sample. Clearly, the

model performed exceptionally well across both cultures.

Ag-gregating across the two cultures, 15:19 (personal), 19:24

Limitations and Future Research

(situational), and 10:11 demographic supported the posited

hypotheses, for a support rate of 81.5% (44:54). The scope of the current study was limited to the prepurchase

search for a Christmas gift of a clothing item. In order to increase the study’s generalizability while maintaining the

fo-Discussion

cus on in-store search for gifts, other scenarios should beexamined including “nonclothing” gifts and other gift-giving Several important results were obtained in the current study.

occasions (e.g., Mother’s Day, Valentine’s Day). First, we unexpectedly uncovered a three-factor solution for

Given that Christmas shopping is typically carried out dur-the dependent measure, namely extent of prepurchase gift

ing a specific time period, memory effects were of great con-search was broken down into general con-search, specific con-search,

Belk, R. W.: Gift-Giving Behavior.Research in Marketing2 (1979): Christmas season to distribute the questionnaire, consumers

95–126. might have forgotten how they had behaved when Christmas

Belk, R. W.: Cultural and Historical Differences in Concepts of Self shopping. It was determined that beyond mid-February, the

and Their Effects on Attitudes Toward Having and Giving, in interest among respondents would have dwindled, and the Advances in Consumer Research, vol. 11, Thomas C. Kinnear, ed., reliability of the data would have been suspect. As such, the Association for Consumer Research, Provo, UT. 1984, pp. 753–760. time frame for the research was very strict. With a greater time Berry, J. W., Poortinga, Y. H., Segall, M. H., and Dasen, P. R.: availability, some weaknesses in the instrument could have Cross-Cultural Psychology: Research and Applications, Cambridge been ameliorated. For example, the time pressure construct University Press, Cambridge, MA. 1992.

measured sensitivity to time pressure rather than the actual Bouchard, J.: The French Evolution.Marketing(September 1983): 60.

situational experience.

With the exception of the third objective wherein we tested Buss, D. M.: Sex Differences in Human Mate Preferences: Evolution-ary Hypotheses Tested in 37 Cultures. Behavioral and Brain

Sci-directional hypotheses linking moderators of search to extent

ences12 (1989): 1–14. of search, much of the remainder of the current study was

Buss, D. M.:The Evolution of Desire: Strategies of Human Mating, Basic exploratory in nature. As such, we did not posit a priori

Books, New York. 1994. expectations regarding the pattern of cross-cultural

differ-Buss, D. M., and Schmitt, D. P.: Sexual Strategies Theory: An Evolu-ences. We simply gauged whether such differences existed in

tionary Perspective on Human Mating.Psychological Review100 the current context. Hence, a crucial area for future research (1993): 204–232.

will be to try to explain such differences. For example, why

Caplow, T.: Christmas Gifts and Kin Network.American Sociological

was a moderator consistently significant (i.e., two or more Review47 (1982): 383–392.

times) in one sample but not in the other (e.g., “bargain Cheal, D.: Showing Them You Love Them: Gift Giving and the hunter” with the French and “close relationship” with the Dialectic of Intimacy.Sociological Review35 (1987): 150–169. English)? Within a given sample, why did a given moderator Chebat, J. C., Laroche, M., and Malette, H.: A Cross-Cultural Compar-yield a differential effect on two or more search indices (e.g., ison of Attitudes Towards and Usage of Credit Cards.International

Journal of Bank Marketing6 (1988): 42–54. “time pressure” in the French sample)? Comparing between

the two cultural groups, why did some moderators have an Clark, T.: International Marketing and National Character: A Review and Proposal for an Integrative Theory.Journal of Marketing54 opposite effect on a given search index (e.g., education with

(October 1990): 66–79. specific information and fashion conscious with salesclerk)?

Fischer, E., and Arnold, S. J.: More Than a Labor of Love: Gender There were four moderators of search that were significant

Roles and Christmas Gift Shopping.Journal of Consumer Research

for all three search indices (“thoughtful giver”, “fashion

con-17 (1990): 333–344. scious”, “costly gift”, and “strict budget”). All four occurred

Gift Retailing: Here Come the Nineties.Gifts and Decorative Accessories

in the English sample, further demonstrating that the English

(December 1987): 156–186. appear to have a more complex process when shopping for

Goodwin, C., Smith, K. L., and Spiggle, S.: Gift Giving: Consumer gifts. Is there a framework and/or a specific set of cultural Motivation and the Gift Purchase Process, inAdvances in Consumer traits that can help explicate these differences? The potential Research, vol. 17, M. E. Goldberg, G. Gorn, and R. W. Pollay,

for future research appears indeed promising. eds., Association for Consumer Research, Provo, UT. 1990, pp.

690–698.

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support of the Social Sciences Green, R. T., and Alden, D. L.: Functional Equivalence in

Cross-and Humanities Research Council of Canada. The data was collected as part Cultural Consumer Behavior: Gift Giving in Japan and the United

of the fourth author’s Master’s thesis presented to the Faculty of Commerce States.Psychology and Marketing5 (1988): 155–168.

and Administration, Concordia University. The authors thank two anonymous Grønhaug, K.: Buying Situation and Buyer’s Information Behavior. reviewers and the participants of the Symposium on Retail and Service Envi- European Marketing Research Review7 (1972): 33–48.

ronment Atmospherics Research (Montreal, October, 1997) for their insightful

Heeler, R., Francis, J., Okechuku, C., and Reid, S.: Gift Versus

comments. Finally, Isabelle Miodek’s role in the data analyses stage also is

Personal Use Brand Selection, inAdvances in Consumer Research,

gratefully acknowledged.

Vol. 6, W. Wilkie, ed., Association for Consumer Research, Ann Arbor, MI. 1979, pp. 325–328.

He´nault, G.: Les Conse´quences du Biculturalisme sur la

Consomma-References

tion.Commerce73 (1971): 78–80. Banks, S. K.: Gift-Giving: A Review and an Interactive Paradigm, in

Advances in Consumer Research, vol. 6, W. Wilkie, ed., Association He´on, E.: Excess Means Success in the Quebec Market.Marketing

for Consumer Research, Ann Arbor, MI. 1979, pp. 319–324. (August 1990): 6.

Beatty, S. E., Kahle, L. R., and Homer, P.: Personal Values and Gift- Horton, R. L.: Some Relationships Between Personality and Con-Giving Behaviors: A Study across Cultures. Journal of Business sumer Decision Making.Journal of Marketing Research16 (1979):

Research22 (1991): 149–157. 233–246.

Beatty, S. E., and Smith, S. M.: External Search Effort: An Investiga- Hui, M., Joy, A., Kim, C., Laroche, M.: Equivalence of Lifestyle tion Across Several Product Categories.Journal of Consumer Re- Dimensions Across Four Major Subcultures in Canada. Journal search14 (1987): 83–95. of International Consumer Marketing5 (1993): 15–35.

Johnson, E. J., and Russo, J. E.: Product Familiarity and Learning New Belk, R. W.: It’s the Thought that Counts: A Signed Digraph Analysis

Jolibert, A. J. P., and Fernandez-Moreno, C.: A Comparison of French Ryans, A. B.: Consumer Gift Buying Behavior: An Exploratory Analy-sis, inContemporary Marketing Thought, vol. 44, O. Bellinger and and Mexican Gift Giving Practices, inAdvances in Consumer

Re-search, vol. 10, Richard P. Bagozzi and Alice M. Tybout, eds., B. Greenberg, eds., American Marketing Association, Chicago, IL. 1977, pp. 99–104.

Association for Consumer Research, Ann Arbor, MI. 1983, pp.

191–196. Saint-Jacques, M., and Mallen, B.: The French Market Under the

Microscope.Marketing(May 1981): 10–15. Joy, A., Kim, C., and Laroche, M.: Ethnicity as a Factor Influencing

Use of Financial Services.International Journal of Bank Marketing Schaninger, C. M., Bourgeois, J. C., and Buss, W. C.: French-English

9 (1991): 10–16. Canadian Subcultural Consumption Differences.Journal of

Mar-keting49 (1985): 82–92. Kim, C., Laroche, M., and Lee, B.: Development of an Index of

Ethnicity Based on Communication Patterns Among French and Schaninger, C. M., and Sciglimpaglia, D.: The Influence of Cognitive English Canadians.Journal of International Consumer Marketing2 Personality Traits and Demographics on Consumer Information

(1989): 43–60. Acquisition.Journal of Consumer Research8 (1981): 208–216.

Laroche, M., Kim, C., Saad, G. and Browne, E.: Determinants of In- Sherry, J. F., Jr.: Gift Giving in Anthropological Perspective.Journal

Store Information Search Strategies Pertaining to a Christmas Gift of Consumer Research10 (1983): 157–168.

Purchase. Working Paper, Concordia University 1997. Sherry, J. F., Jr., and McGrath, M. A.: Unpacking the Holiday Pres-Lefranc¸ois, P. C., and Chatel, G.: The French Canadian Consumer: ence: A Comparative Ethnography of Two Gift Stores, in

Interpre-Fact and Fancy.The Canadian Marketer2 (1967): 4–7. tive Consumer Research, E. Hirschmann, ed., Association for Con-sumer Research, Provo, UT. 1989, pp. 148–167.

Locander, W. B., and Hermann, P. W.: The Effect of Self-Confidence

and Anxiety on Information Seeking in Consumer Risk Reduction. Sherry, J. F., Jr., McGrath, M. A., and Levy, S. J.: The Dark Side of

Journal of Marketing Research16 (May 1979): 268–274. the Gift.Journal of Business Research28 (1993): 225–244. Smith, S. M., and Beatty, S. E.: An Examination of Gift Purchasing Mallen, B.:French Canadian Consumer Behaviour: Comparative Lessons

Behavior: Do Shoppers Differ in Task Involvement, Search

Activ-from the Published Literature and Private Corporate Marketing

Stud-ity, or Perceptions of Product Selection Risk?, inAMA Educator’s ies.The Advertising and Sales Executives Club of Montreal,

Mon-Proceedings, Robert F. Lusch, M. E. Goldberg, G. Gorn, and R. treal, Canada. 1977.

W. Pollay, eds., American Marketing Association, Chicago, IL. Manrai, L. A., and Manrai, A. K., eds.:Global Perspectives in

Cross-1985, pp. 69–74.

Cultural and Cross-National Consumer Research, The Haworth

Sprott, D. E., and Miyazaki, A. D.: Gift Purchasing in a Retail Setting: Press, Binghamton, NY. 1996.

An Empirical Examination, inAMA Winter Educators’ Conference, Mattson, B. E.: Situational Influences on Store Choice. Journal of

American Marketing Association, Chicago, IL. 1995, pp. 1–19.

Retailing58 (1982): 46–58.

Tamilia, R. D.: A Cross-Cultural Study of Source Effects in a Canadian Muller, T. W., and Bolger, C.: Search Behaviour of French and English

Advertising Situation, inMarketing, J. M. Boisvert and R. Savitt, Canadians in Automobile Purchase.International Marketing Review

eds., Administrative Sciences Association of Canada, Montreal. 2 (Winter 1985): 21–30.

1978, pp. 250–255.

Otnes, C. C.: A Study of Consumer External Search Strategies Per- Thomas, D. R.: Culture and Consumption Behaviour in English and taining to Christmas Shopping. Unpublished doctoral disserta- French Canada, inMarketing in the 1970s and Beyond, B. Stidsen, tion, University of Tennessee, 1990. ed., Administrative Sciences Association of Canada, Montreal. Otnes, C., Lowrey, T. M., and Kim, Y. C.: Gift Selection for Easy 1975, pp. 255–261.

and Difficult Recipients: A Social Roles Interpretation.Journal of Trivers, R.: The Evolution of Reciprocal Altruism.Quarterly Review Consumer Research20 (1993): 229–244. of Biology46 (1971): 35–56.

Palda, K.S.: A Comparison of Consumers’ Expenditures in Quebec Vary, F.: Quebec Consumer Has Unique Buying Habits.Marketing and Ontario.Canadian Journal of Economics and Political Science (March 1992): 28.

33 (1967): 26.

Vincent, M., and Zikmund, W.: An Experimental Investigation of Punnett, B. J.: Preliminary Considerations of Confucianism and Situational Effects on Risk Perception, inAdvances in Consumer Needs in the PRC.Journal of Asia-Pacific Business1 (1995): 25–42. Research, vol. 2, M. J. Schlinger, ed., Association for Consumer

Research, Chicago, IL. 1975, pp. 125–129. Rogers, E. M.:Diffusions of Innovations, The Free Press, New York.

1962. Wells, W. D., and Tigert, D. J.: Activities, Interests and Opinions.

Journal of Advertising Research11 (August 1971): 17–35. Rucker, M., Leckliter, L., Kivel, S., Dinkel, M., Freitas, T., Wynes,

M., and Prato, H.: When the Thought Counts: Friendship, Love, Wolfinbarger, M. F.: Motivations and Symbolism in Gift-Giving Be-Gift Exchanges and Be-Gift Returns, inAdvances in Consumer Re- havior, inAdvances in Consumer Research, vol. 17, M. Goldberg

search, Vol. 18, R. Holman and M. Solomon, eds., Association et al., eds., Association for Consumer Research, Provo, UT. 1990, pp. 699–706.