DIFFERENCES OF

LEXICAL STRESS ASSIGNMENTS

IN BRITISH AND AMERICAN ENGLISH

A Thesis

Presented to the Graduate Program in English Language Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements

for the Degree of Magister Humaniora (M. Hum) in English Language Studies

Carla Sih Prabandari

056332013

ENGLISH LANGUAGE STUDIES

THE GRADUATE PROGRAM

SANATA DHARMA UNIVERSITY

DIFFERENCES OF

LEXICAL STRESS ASSIGNMENTS

IN BRITISH AND AMERICAN ENGLISH

A Thesis

Presented to the Graduate Program in English Language Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements

for the Degree of Magister Humaniora (M. Hum)

in English Language Studies

Carla Sih Prabandari

056332013

ENGLISH LANGUAGE STUDIES

THE GRADUATE PROGRAM

SANATA DHARMA UNIVERSITY

STATEMENT OF ORIGINALITY

This is to certify that all the ideas, phrases and sentences, unless otherwise

stated, are the ideas, phrases and sentences of the thesis writer. The writer

understands the full consequences including degree cancellation if she takes

ABSTRACT

CARLA SIH PRABANDARI. (2008). DIFFERENCES OF LEXICAL STRESS ASSIGNMENTS IN BRITISH AND AMERICAN ENGLISH. Yogyakarta: English Language Studies, Graduate Program, Sanata Dharma University

The present study is an attempt to investigate the differences between British English (BE) and American English (AE) from the view point of lexical stress assignments. The study is aimed at answering two research questions. The first is how BE and AE differ in the assignments of lexical stress. The second is questioning the linguistic factors which account for the differences.

As the bases of the analysis, some theories are reviewed. The first is the theory of English phonology which mainly discusses English syllable structure and English stress systems. Second, the discussion on English morphology is also presented because morphology also influences stress placement. The last is a brief history of the source of English vocabulary. The study is a dictionary analysis. It means it relies on the dictionary as the source of data. The data were collected from the Oxford Advanced Learner’s Dictionary, 7th ed., published in 2005.

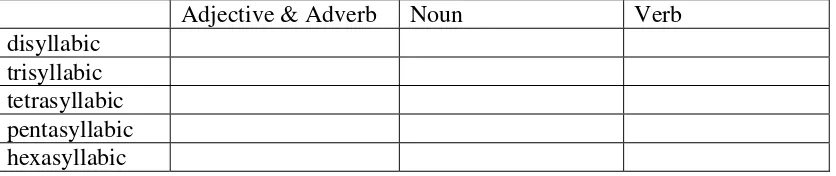

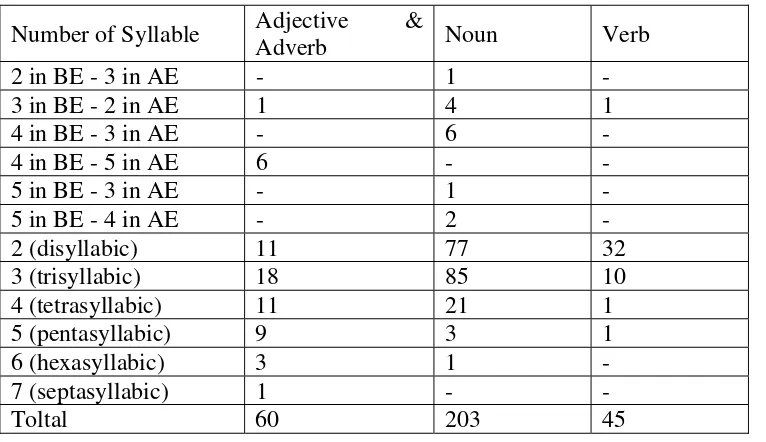

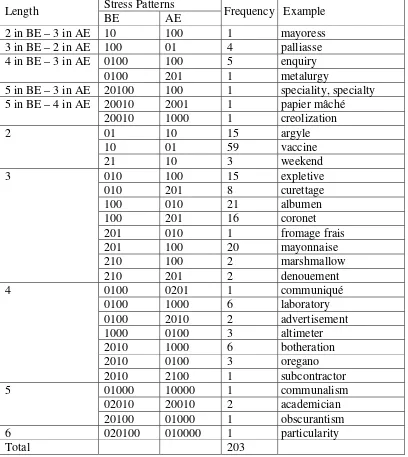

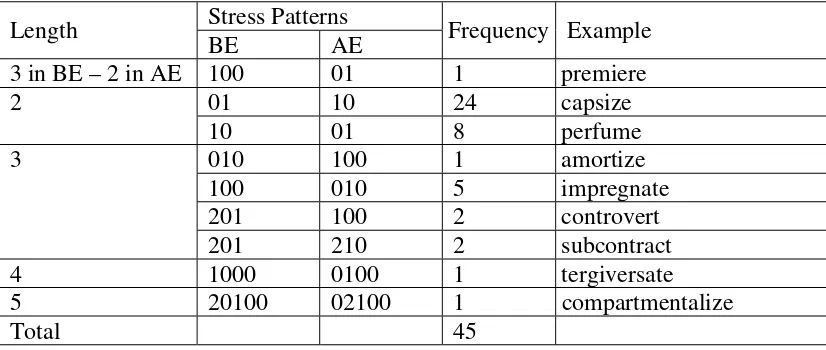

The first part of the findings is the result of a thorough manual scanning of the dictionary which yielded total of 308 words showing the different stress placements in BE and AE. They consist of 60 adjectives and adverb, 203 nouns and 45 verbs. Based on the syntactic categorization of the lexical items, in adjectives and adverbs, the primary stress in BE tends to fall farther to the left and in AE to the right. The primary stress of nouns in BE also tends to fall farther to the left but in AE to the right. Finally, the phenomenon of stress differences in verbs happens to be the opposite of the previous categories. In BE, the stress of the verbs falls farther to the right than that of AE.

The second part of the findings shows that the linguistic factors which account for the different stress assignments in BE and AE are phonological factors, namely syllable weight and stress assignment rules, morphological processes and etymological background of words.

ABSTRAK

CARLA SIH PRABANDARI. (2008). DIFFERENCES OF LEXICAL STRESS ASSIGNMENTS IN BRITISH AND AMERICAN ENGLISH. Yogyakarta: Kajian Bahasa Inggris, Program Pasca Sarjana, Universitas Sanata Dharma.

Penelitian ini merupakan sebuah upaya untuk mempelajari perbedaan antara British English (BE) dan American English (AE) dari sudut pandang letak tekanan kata. Penelitian ini bertujuan untuk menjawab dua pertanyaan yang diajukan. Pertama, bagaimana perbedaan BE dan AE dalam letak tekanan kata. Kedua, faktor linguistik apa yang berpengaruh dalam perbedaan letak stress.

Beberapa teori diulas sebagai dasar dalam menganalisis data. Pertama adalah teori tentang Phonology bahasa Inggris yang mencakup struktur suku kata dan sistem tekanan kata dalam bahasa Inggris. Kedua adalah paparan mengenai morphology bahasa Inggris karena morphology merupakan faktor yang mempengaruhi letak tekanan. Terakhir adalah tinjauan singkat mengenai sejarah asal usul kosa kata dalam bahasa Inggris. Penelitian ini menggunakan metode analisis kamus. Jadi data yang dikupmulkan bersumber dari kamus. Sumber data adalah dari kamus Oxford Advanced Learner’s Dictionary, edisi 7,terbitan tahun 2005.

Bagian pertama dari hasil penelitian ini merupakan hasil dari proses penelusuran kamus yang berhasil mengidentifikasi total keseluruhan 308 kata yang mendapat tekanan berbeda dalam BE and AE. Angka tersebut terdiri dari 60 kata sifat dan kata keterangan, 203 kata benda, dan 45 kata kerja. Berdasarkan penggolongan menurut jenis kata, pada kata sifat dan kata keterangan, tekanan primer cenderung terletak lebih ke kiri dalam BE dan lebih ke kanan dalam AE. Tekanan primer pada kata benda juga menunjukkan kecenderungan yang sama, yaitu lebih ke kiri pada BE dan ke kanan pada AE. Yang terakhir, fenomena perbedaan stress pada verb menunjukkan hal yang berlawanan dari kata sifat, kata keterangan maupun kata benda. Di BE tekanan pada verb cenderung lebih ke kanan.

Bagian kedua dari hasil penelitian ini menunjukkan bahwa faktor linguistik yang mempengaruhi peletakan tekanan adalah faktor fonologi, yaitu berat ringannya suku kata dan sistem aturan tekanan, faktor morfologi, yaitu proses-proses morfologi, and faktor etimologi yaitu latar belakang asal-usul kata.

PREFACE

This thesis tries to look at the differences between BE and AE as the two most prominent varieties of English from the view point of the words stress placement. In English there is a special relationship between different parts of a word. In an English word of two or more syllables, one of these will have the prominence or stress. If a learner does not stress one syllable more than another or stresses the wrong syllable, it may be very difficult for the listener to identify the word. This is because the stress pattern of a word is an important part of its identity for the native speaker. However, in this study, the word stress differences between BE and AE do not seem to cause a serious problem of intelligibility.

BE and AE referred to in this study may be considered as two different dialects of English. However, they may also be treated as different languages although they are by far mutually intelligible. Just as two different languages can have their own linguistic features, so do BE and AE. They may have their own grammar. They may have their own phonological systems. The first objective of the study is to investigate how much BE and AE are different in terms of word stress placements. The second objective is to identify linguistic factors which may be responsible for the variations to appear. In other words, it is meant to find out the reasons why such variations are possible to occur. However, this study does not aim at judging which variety is better. It is because we all know that all languages in the world and all varieties of any language are linguistically equal. Furthermore, this study does not suggest that we over-emphasize the differences between the two varieties and that one variety is better than the other.

I would like to praise and thank God for His blessings and providence. He has sent me so many helping hands that finally I managed to finish this thesis.

First of all, I would like to address my special thanks to Dr. Fr. B. Alip, M.Pd. M.A., my advisor, for his guidance, correction and encouragement. I am sincerely grateful to him also for sparing his invaluable time for consultation.

Language Studies at Sanata Dharma University. They have motivated me to learn and study more to improve my professionalism. Special thanks and appreciation are also due to all my classmates for their sincerity to share their knowledge. I do hope that they also benefit from our friendship.

Let me also thank all my colleagues at the English Language Education Study Program for their encouragement and attention. They have been the source of my motivation to be a more professional teacher.

Last, but not least, I am indebted to my husband and children, my father and mother, my brothers and sisters and my family-in-law for their love, support and encouragement they have granted me throughout the writing of this thesis.

LEMBAR PERNYATAAN PERSETUJUAN

PUBLIKASI KARMA JILMLAR UNTUK KEPENTINGAN AKADEMIS

Yang bertanda tangan di bawah ini, saya mahasiswa Universitas Sanata Dharma:

Nama : Carla Sih Prabandari

Nomor Mahasiswa : 056332013

Demi pengembangan ilmu pengetahuan, saya memberikan kepada Perpustakaan Universitas Sanata Dharma karya ilmiah saya yang berjudul:

DIFFERENCES OF LEXICAL STRESS ASSIGNMENTS IN BRITISH AND AMERICAN ENGLISH

beserta perangkat yang diperlukan (bila ada). Dengan demikian saya memberikan kepada Perpustakaan Universitas Sanata Dharma hak untuk menyimpan, mengalihkan dalam bentuk media lain, mengelolanya dalam bentuk: pangkalan data, mendistribusikan secara terbatas, dan mempublikasikannya di Internet atau media lain untuk kepentingan

akademis tanpa perlu meminta ijin dari saya maupun memberikan royalti kepada saya selama tetap mencantumkan nama saya sebagai penulis.

Demikian pernyataan ini yang saya buat dengan sebenarnya.

Dibuat di Yogyakarta

Pada tanggal: 5 Mei 2008

Yang menyatakan

TABLE OF CONTENTS

CHAPTER II. THEORETICAL REVIEW ……… 8

A. Theoretical Review ...………... 8

1. The English Syllables ...………. 8

a. Syllable Structure ………... 9

b. Syllabification …… ………... 10

c. Types of Syllables ………... 14

2. Stress Patterns in English ………... 15

a. Definition of Stress ………... 15

b. Stress and Syllable Structure ……… 16

c. Ambisyllabicity ………... 16

d. Degrees of stress ………... 17

f. Stress Placement ………..……….. 21

4. Origin of English Vocabulary ………... 29

a. Anglo-Saxon Bases ………... 30

1. Ling and Grabe’s Study on British and Singapore English ..………… 34

2. Berg’s Study on British and American English ..……….. 34

C. Theoretical Framework ………... 35

CHAPTER III. RESEARCH METHODOLOGY ……….. 40

A. Research Method ………... 40

B. Data Source and Data Gathering ………... 40

C. Data Processing ………... 41

D. Data Analysis ………... 42

CHAPTER IV. RESEARCH FINDINGS, ANALYSIS AND DISCUSSION ………..……….…… 44

A. Research Findings ………. ………... 44

1. Adjectives and Adverbs ………... 45

2. Nouns ………... 47

3. Verbs ………... 50

B. Analysis and Discussion ………... 51

a. Adjectives and Adverbs ……….... 52

b. Nouns ………... 57

c. Verbs ………... 64

2. Morphological Influence on Stress Placement in BE and AE ……….. 68

a. Prefixation ………... 68

b. Suffixation ………... 74

c. Conversion ………... 81

d. Backformation ………... 86

e. Compound Stress………... 87

3. Etymological Influence of Stress ……….. 89

a. French Loans ………... 89

b. Loans from other languages ……….. 90

CHAPTER V. CONCLUSIONS AND SUGGESTIONS ……….. 97

A. Conclusions ………... 97

B. Suggestions ………... 101

BIBLIOGRAPHY ………... 103

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

U : Ultimate (Final)

PU : Penultimate (Second from the last) APU : Antepenultimate (Third from the last) PAPU : Pre-antepenultimate (Fourth from the last) APAPU : Ante-Pre-antepenultimate (Fifth from the last) MSR : Main Stress Rules

LVS : Long Vowel Stressing ESR : Early Stress Requirement DSS : Derivational Secondary Stress SCA : Stress Clash Avoidance ASR : Alternating Stress Rule BE : British English

LIST OF FIGURES

Page

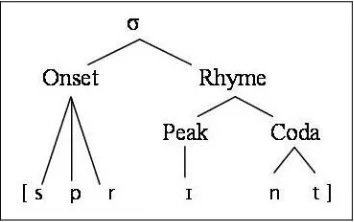

Figure 2.1 The basic structure of a syllable ……….. 10

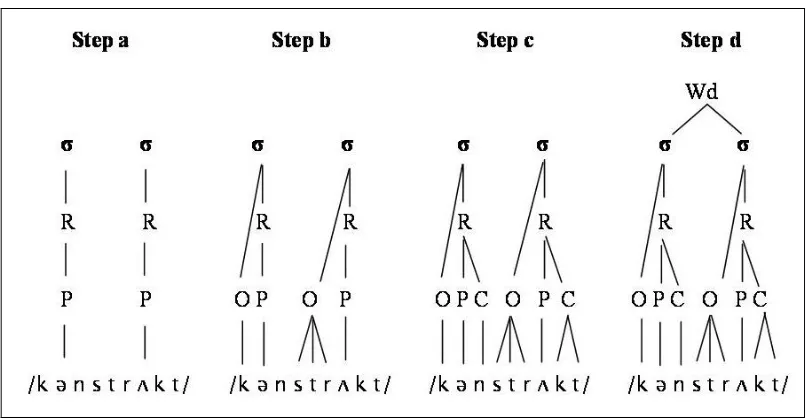

Figure 2.2 The steps of setting up a syllable ……… 11

Figure 2.3 Example of syllabification of the verb construct ……...……... 12

Figure 2.4 The syllabification of the word sprint …..……….. 13

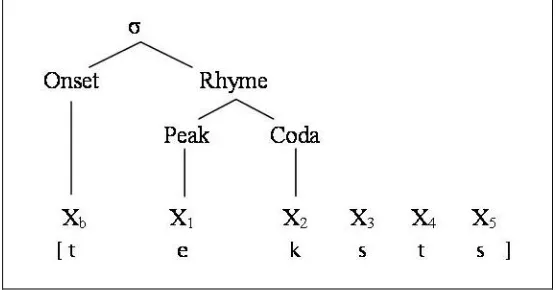

Figure 2.5 The syllabification of the word mind …..……… 13

Figure 2.6 The syllabification of the word texts …..……… 13

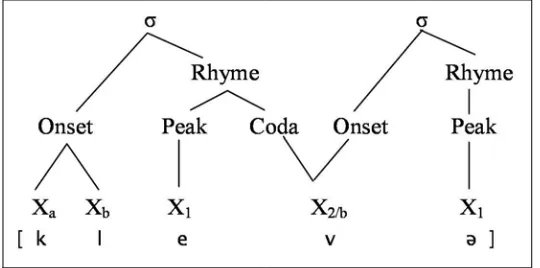

Figure 2.7 Coda capture: Ambisyllabic consonant ………... 17

LIST OF TABLES

Page

Table 3.1 Classification of raw data ………. 42

Table 3.2 Summary of data classification ………. 42

Table 4.1 Frequency distribution of stress divergent words ………. 44

Table 4.2 Adjectives and Adverb Stress Patterns ………. 45

Table 4.3 Noun Stress Patterns ………. 48

Table 4.4 Noun Stress Patterns ………. 50

Table 4.5 Stress Patterns of Adjectives ending in –ary/-ory ………... 76

Table 4.6 Nouns ending in –y/-ary/-ory ………...…..……….. 77

Table 4.7 Suffix –ly ……….. 77

Table 4.8 Adjectives ending in –ate ………..………... 78

Table 4.9 Verbs ending in –ate ………. 80

Table 4.10 Backformation of verbs ending in –ate ………..………... 87

Table 4.11 French Loan Compound Words ………. 88

Table 4.12 Compound Words ………... 88

Table 4.13 Latin Loanwords with PU stress in BE ……….. 91

CHAPTER I

INTRODUCTION

This chapter consists of five sections. The first is the background of the

study. It discusses the reasons underlying the present study. The second section is

the problem limitation which narrows down the scope of the study. The third

section is the problem formulation. The last two sections are the objectives and

the benefits of the study.

A. Background of Study

The use of speech sound for communication is one of characteristics of

human language. It is actually a secondary function of human organs (Aitchison,

2003). Language makes use of a limited number of sounds, which are

meaningless. Yet, those limited sounds can be combined to form an unlimited

number of meaningful units of words (Carstairs-McCarthy, 2002). This feature of

language has been called duality. Speech sound, however, are not randomly

combined. There are rules to obey in order to build a possibly acceptable word.

Words, therefore, can be broken down into individual sound segments. In the case

of English, besides rules for combining sound segments into words, there are also

rules that govern the stress placements. Violating the stress rules may result in a

change in meaning, or, even worse, in a misunderstanding. Furthermore, linguists

consider word stress as a high priority in any pronunciation teaching (Kenworthy,

1987).

As an English teacher, I often have to answer my students’ question about

British or American English. After all, English has spread too far and wide to be

uniform. As a matter of fact, there are numerous varieties of English. People

recognize British English and American English as the most prominent varieties.

Logically, for Indonesian people being able to speak either of the two varieties is

ideal because they consider British English and American English as the two most

influential and prestigious varieties. Since Indonesians are mostly foreign learners

of English, it is useful, therefore, to choose one of them as their reference accent.

Due to a series of historical events, English has developed into a lot of

varieties. Two most prominent varieties have been mentioned above. One is

Standard British English and the other is Standard American English. It has been

known that British and American English differ in some respects. Among others

are lexical, phonological and syntactic differences. The structure of subjunctive

exhibits one of syntactic differences (Quirk, Greenbaum, Leech and Svartvik:

1985), as seen in the example below:

BE: The employees demanded that he should resign.

AE: The employees demanded that he resign.

In addition, AE uses simple past tense in some case where BE prefers to use

present perfect tense, e.g. He’s just gone home and He just went home. As for

difference in spelling, some are quite systematic, e.g. British word ending -our

and -ise are -or and -ize in AE respectively, and some apply to individual

words, such as BE cheque and programme become check and program in AE

(Quirk et al. 1985). Examples of lexical differences are abundant. Below are a few

BE AE

Mobile phone cellphone

Petrol gas

Tap faucet

Cooker stove

Sweets candy

Among those aspects which differentiate British English from American

English, however, phonological differences are the most easily observed.

Phonological differences between British and American English cover both

segmental level, such as phoneme variations, and suprasegmental levels, such as

pronunciation and stress placement. In terms of phoneme variation, BE is known

as a non-rhotic dialect, while AE is a rhotic one (McMahon, 2002). In BE word

final sound /r/ in words like war and care is not pronounced unless it is followed

by a word beginning with a vowel, but in AE /r/ is retained. In addition, a number

of systematic sound correspondence can be identified, e.g. the BE diphthong /əʊ/

in know, go and boat is pronounced as /ʊo/ in EA. The word garage is

pronounced differently in British and American. Besides, American English uses

flapping sound, which is not present in British English. American would

pronounce the /t/ and /d/ in the words writer and rider as almost the same /raiDer/.

All these indicate that phonology may cause serious problems in the

process of teaching and learning English. Of course, there are plenty other

evidence showing the differences between BE and AE but they are irrelevant to be

discussed here. However, for most Indonesian, there is another problem which is

learning a language means learning to speak, pronunciation becomes important.

Being able to speak and pronounce words with the right stress is important

because the primary function of language is for oral communication. Thus,

pronunciation is the gist of language. In many occasions, language mastery is

closely associated with education, so any language error affects the credibility of

the speaker. We may ask ourselves: how often we judge one's overall competence

from their pronunciation. Although it is not always true, we often consider people

with sloppy pronunciation as less competent than those with careful

pronunciation. Moreover, superior language skills are especially important to

businesses whose consumers are educated professionals, such as physicians and

lawyers. And if the speaker represents a business, it will be a reflection of the

general quality of the business.

There is a danger when the teachers are not aware that Indonesian and

English are two different languages in nature. The facts that Indonesian is a

relatively syllable-timed language and English is a stress-timed language are often

overlooked. In Indonesian, the length of utterances is very much influenced by the

number of syllables in them. In contrast, the length of utterances in English

depends mostly on the number of stressed elements in them. As a consequence of

not realizing this significant difference, many English teachers speak without

paying attention to the stress patterns. It means that they fail to be a good model

for their students. Therefore, their students often make mistakes in stress

placement.

Correct word stress patterns are essential for the learner’s production and

speaker produces a word with the wrong stress pattern, an English listener may

have difficulty in understanding the word, even if the individual sounds have been

well pronounced. Before expecting that their students can speak with clear

pronunciation, an English teacher should have awareness of word stress and

sentence stress (Kelly, 2000). Therefore, in introducing a new vocabulary item,

for example, the teacher must have some considerations, such as what the students

need to know about the new word to be introduced: meaning, spelling,

pronunciation and even collocation. With regards to pronunciation, stresses are

important. Learners need to develop a concern for stresses in their pronunciation.

It is difficult for a learner to do it themselves, so it is the teacher’s job. As the

teachers themselves have gained awareness of stress, they can and should find

various ways to encourage students’ awareness of stress, too.

B. Problem Limitation

There are many varieties of English other than British and American. All

those other varieties are just as worthy of study as British and American.

However, these two varieties are the ones spoken by most native speakers of

English and studied by most foreign learners. British English (BE) in this study

refers to the form of English which is also known as Received Pronunciation (or

RP). Meanwhile, American English (AE) in this study refers to the variety of

English spoken mostly in North America, some people also call it General

American (GA). In Oxford Advanced Learner's Dictionary, it is referred to as

The focus of this study is on how contemporary British English differs

from American in terms of the lexical stress assignments. That is, in comparing

the two varieties, it is convenient to take one as the basis for comparison and to

describe the other by contrast with it. This study takes British as its basis and

describes American in relation to that basis. It is done because the main source of

data is taken from the whole population of the Oxford Advanced Learner's

Dictionary, 7th edition, published in 2005.

Among other differences, pronunciation is considered the most prominent.

It includes consonants and vowel articulation and distribution and stress patterns.

However, this study only focuses on the different lexical stress assignments

between BE and AE. The differences in consonant and vowel articulation and

distribution will be discussed as a supporting factor influencing the different

stress assignments.

C. Problem Formulation

The following questions are formulated in attempt to study the variation of

lexical stress placement in British and American English:

1. How is the lexical stress assignment in British English different from that in

American English?

D. Objectives of Study

The objectives of the study are set as follows:

1. It aims to reveal the differences between British English and American

English in terms of lexical stress assignments.

2. It also attempts to identify possible factors which account for the differences.

E. Benefits of Study

The results of the analysis on the difference between BE and AE will

hopefully provide some insights for English teachers and learners. Firstly, I hope

that English teachers in Indonesia are more aware that stress placement is a

potential problem faced by Indonesian learners. Secondly, after being aware of the

differences, they become more consistent in using and teaching the variety of

English that they would teach to their students. By such awareness hopefully they

will not over-emphasize the differences between BE and AE but can be better

models for their students. Thirdly, the results of study can give some contributions

to the development of linguistic study, especially in English phonology. It can

help people understand more about the nature of the English language and its

CHAPTER II

LITERATURE REVIEW

This chapter deals with 3 major parts. The first part is a review of previous

studies on the different stress patterns among some varieties of English. The

second part presents a theoretical review. This section will discuss the syllable

structure in English, the English stress system, the word formation processes and

a brief history of the English Vocabulary. The last section is the theoretical

framework upon which the present study is based.

A. Theoretical Review

This section is divided in four major parts. Stress is property of syllables;

therefore, prior to the discussion of stress system, we will discuss the syllable

structure in English. Following the discussion on syllables structure and stress in

English is the review of morphological processes, in which we shall see the

relevance with phonology. The last part of the theoretical review will present a

brief discussion of the history of English and the source of English vocabulary.

1. The English Syllables

Just as segments are composed of features, the syllable itself is made of

smaller constituents that are organized in a hierarchical structure. Furthermore,

native speakers also demonstrate knowledge that syllables have internal structure.

They can identify whether a word is possible or not by seeing the elements

contained in it. Native speakers of English, for instance, can say that the word

blide sounds English while dlide does not and cannot be an English word because

a. Syllable Structure

Native speakers of a language are usually able to count the syllables

contained in a word without any difficulty even though they do not have formal

knowledge of phonology. They know that the word book consists of a single

syllable, while potato three syllables. However, the definition of syllables is not

that simple. According to Giegerich (1992), there are two principles to follow in

defining what syllables are. They are the sonority principle and number of

phonemes contained in a syllable. Obeying the two principles, we can explain

more complexities of syllable structure. The complexities include the boundary

between words, boundary within words, the maximum number of phonemes in a

syllable and phonotactic constraints.

Syllable structure varies among languages. The most common structure is

CV, that is, a sequence of a single consonant followed by a vowel. Many

languages allow only CV or CVC syllables, like Indonesian. English, however,

permits very complex syllable structures. It allows up to three consonant both

before and after the vowel or Peak.

A syllable is analyzable into an Onset, which is optional, and a Rhyme,

which is built upon a Peak/Nucleus and an optional Coda (McMahon, 2002). Most

syllables start with a consonant or a consonant sequence known as the onset.

However, onset is an optional part of a syllable. We are familiar with the term

rhymes. We can find them in poetry and nursery rhymes. The rhyme of a syllable

may contain an obligatory peak or nucleus and an optional coda. The peak or

combination of consonants. Let’s take an example. The syllable structure of the

English word sprint /spr ɪ nt/ is illustrated below.

Figure 2.1 The basic structure of a syllable

b. Syllabification

The syllabification of monosyllabic words as in the example above is not

problematic. In longer words, however, it may be confusing as to whether

intervocalic consonants belong to the coda of the previous syllable or the onset of

following. In setting up syllables, there are four steps to follow (O'Grady,

Dobrovolsky & Katamba, 1996). The four steps elaborated by O’Grady et al. are

especially important in uncovering the syllabification of disyllabic and

Figure 2.2 The steps of setting up a syllable

To see the syllabification of the verb consrtuct, let’s follow the steps as

described in Figure 2.3. In step a, we can find two vowels, which means that the

word consists of 2 syllables. In step b, there is only one consonant to the left of /ǝ/

but there are 4 consonants to the left of /ʌ/. Therefore, we must decide whether all

the four can be the onset of the second syllable. First, it should be noted that the

maximum number of consonants occupying the onset position is three. Then we

must check whether the three violate the phonotactic constraints or not.

Phonotactic constraints mean s restrictions on possible combination of sounds

violate the phonotactic constrains can be grouped together forming the onset of

the second syllable. Grouping the intervocalic consonants to form onset as long as

they do not violate phonotactic constraints is called Onset Maximization Principle

(Carr, 1993). Finally, the /n/ is the one left, so it must belong to the coda of the

first syllable, and /k, t / constitute the coda of the second syllable.

Figure 2.3 Example of syllabification of the verb consrtuct

Giegerich (1992) uses X-positions to describe syllable structure. He

mentions that a syllable may consist of a peak, which is the only obligatory

element, and an optional onset and coda. A core syllable can contain one up to

five X-positions; two X-positions on the onset and three on the rhyme. Other

exceeding elements within a syllable which violate the sonority principle and

phonotactic constraints are called appendices. Thus, the words sprint, mind and

Figure 2.4 The syllabification of the word sprint

Figure 2.5 The syllabification of the word mind

Figure 2.6 The syllabification of the word texts

In Figures 4.4 – 4.6 above, Xa, X4 and X3-5 in sprint, mind and texts respectively

are appendices, that is, they are beyond the core syllable as for they do not

conform the sonority principle. The syllable sonority principle requires that the

core syllable must show an increase in sonority starting from the onset and

c. Types of Syllables

Syllables can be classified according to their internal structure. We can

classify types of syllables into whether they are open or closed and whether they

are light or heavy.

1) Open and Closed Syllables

According to the rhyming (Giegerich, 1992), syllables can be classified

into open and closed syllables. An open syllable is one which ends in a vowel or

diphthong. In other words, it has no coda and the rhyme is composed of the vowel

as the peak. In contrast, a closed syllable is one which ends in a consonant or

consonant sequence, or, in other words, it has a coda. For example, the word

banana, which is a trisyllabic word, consists of three open syllables; and the word

absent consists of two closed syllables.

2) Light and Heavy Syllables

A syllable can either be light or heavy (Giegerich, 1992). Syllable weight

is also determined by its rhyme. A light syllable is one of which contains a lax

vowel with no coda. A heavy syllable, therefore, is one which contains either a lax

vowel with a coda or a tense vowel with or without a coda. For instance, the first

syllable of the word depend /dɪ.pend/ is light, but the second is heavy. The first

syllable only contains a lax vowel as the peak in the rhyme, which means it

occupies one X-position in the rhyme, while the second contains a lax vowel plus

two consonants occupying three X-positions in the rhyme. In other words, light

syllables have simple rhyme and heavy syllables have complex rhyme.

A core syllable contains 5 X-positions at the most, 2 on the onset, and 3

consonants, it means they contain more than 3 X-positions in the rhyme. This

special type of syllable is called superheavy syllable (Laszlo, 2005) since it

contain a core syllable and appendices. A superheavy syllable may contain a tense

vowel or diphthong and is closed, or a lax vowel closed by two or more

consonants.

The notions of light and heavy syllables overlap with the idea of open

and closed syllables. While it is true that a light syllable is usually open, the

reverse is not always true because an open can either be light or heavy as found

the word prefer /prɪ. fɜ:(r)/. The word contains two open syllables: one light and

one heavy.

The concept of syllable weight is crucial in relation to stress system,

which will be discussed in the next part.

2. Stress Patterns in English

a. Definition of Stress

Stress is the property of syllable. If we stress a word, it means we produce

certain syllable of the word with greater prominence. We can stress a syllable by

pronouncing it louder, longer or with significantly higher or lower pitch (Collins

and Mees, 2003; Fromkin, Blair & Collins, 1996). In English, stress is very

important, be it of words or sentences. Thus we can say that stress is phonemic in

English. It means that stress is a potential factor which can differentiate meanings

of words and it is often unpredictable. Assigning different stress to different

syllable in a word may result in different meaning. For instance, the word object

may have initial stress, meaning a thing, which is a noun. The same word with

Poedjosoedarmo (2006: 149) argues that “the rise in status of word stress

is closely related to the so-called the Great Vowel Shift.” Among the

consequences of the Great Vowel Shift are the loss of final –e in some words and

the aspiration of phonemes /p, t, k/ in some other words. The adoption of strong

word stress in English also results in the rise of several diphthongs and new

vowels which, at the end, reduces the number of syllable in a word. Therefore,

daily English words now tend to be monosyllabic.

b. Stress and Syllable Structure

Syllable structure plays important roles in determining the stress

assignment. A stressed syllable must be heavy and unstressed one is normally

light (Giegerich, 1992, Carr, 1993). Any stressed syllable, whether it is in a

monosyllabic or part of a polysyllabic word must have a complex rhyme. It means

that the rhyme in the syllable must consist of two X-positions at the minimum. In

an open syllable, the X-positions are occupied by a tense vowel or a diphthong.

On the other hand, in a closed syllable, the X-positions can be occupied by a lax

or tense vowel plus coda.

c. Ambisyllabicity

If we syllabify the word clever /kle.və/, we shall find that the word is

composed of two light syllables. Yet the stress is assigned to the first syllable.

This seems to violate the rule that a stress syllable must be heavy. Why does the

rule seem inapplicable? If we syllabify the word then assign the stress on the

penultimate, we will find that the /v/ belongs to both the first syllable as a coda

and second syllable as an onset. The condition of a consonant which is associated

consequence of the stress assignment (Giegerich, 1992). The ambisyllabic /v/

make in the first syllable become heavy. Thus, it agrees with the rule that a stress

syllable must be heavy. The syllable structure can be seen below:

Figure 2.7 Coda Capture: Ambisyllabic Consonant

d. Degrees of stress

Stress patterns present one of the most difficult problems in learning

English. One reason for this is that many polysyllabic words have more than one

possible stress pattern, and we must consider carefully which one is

recommended. Secondly, the stress of many words changes in different contexts,

and it is necessary to indicate how this happens, as in compound words. Thirdly,

there is no straightforward way to decide on how many different levels of stress

are recognizable.

Experts distinguish degrees of stress differently (Fox, 2000). Some experts

argue that stress system is recognized with accented and unaccented syllable.

Some others distinguish the degree of stress into three, namely primary, secondary

and unstressed. Collins and Mees (2003) argue that the characteristics of stressed

and unstressed syllables can be observed in terms of intensity, pitch, vowel quality

and vowel quality, namely rhythmic prominence, intonational prominence and

articulatory prominence. On the basis of loudness, pitch and quality of vowels,

however, following Wardhaugh (2003), Cruttenden (1997), Balogne and

Szentgyorgy (2005) classify degrees of stress into major stress, minor stress and

zero stress or unstressed. The major stress covers both primary and secondary

stress.

Primary stress is the strongest stress. It is normally indicated by a vertical

mark [╵] placed above the line, at the beginning of the syllable, as in 'dirty.

Primary stress is often perceived as the loudest syllable, highest pitch, and full

quality of vowel (Wardhaugh, 2003). It is the nuclear accent near the end of the

intonation phrase. Monosyllabic content words usually receive a primary stress

but the stress may not be indicated.

The second major stress is called the secondary stress. It is weaker than

primary stress. Where it is necessary to show secondary stress, it is indicated by a

vertical mark below the line at the beginning of the syllable [╷]. Although

secondary stress is weaker than primary, the syllable with secondary stress must

also be heavy. The vowel undergoing secondary stress is characterized by the

fullness, the loudness, but not necessarily high pitch (Wardhaugh, 2003).

Secondary stress may be found in polysyllabic words or compound words. In the

example, the word education [╷e.djʊ.╵keɪ.ʃn] contains 4 syllables. The primary

stress falls on the penult and the secondary stress falls on the word initial.

Minor stress is also called tertiary stress. A tertiary stress may occur in

polysyllabic words. Wardhaugh (2003) says when a syllable is relatively weak but

a tertiary stress is low pitch, not loud, but contain full vowel. Tertiary stress is not

indicated by any marks, but it must fulfill the weight requirement. Thus, a syllable

with a tertiary stress must be heavy. Let’s study the example. In the trisyllabic

word educate [╵e.djʊ.keɪt], the primary stress falls on the antepenult, but since the

ultimate syllable is also heavy, it receives a tertiary stress.

Syllables which are not assigned major or minor stress are called Zero

stress or unstressed syllables. Unlike stressed syllables, unstressed syllables are

left unmarked. An unstressed syllable must be light in structure. Referring to the

example above, we can see that in the word education the antepenultimate syllable

is unstressed.

To sum up, the degrees of stress of stress in a syllable depend very much

on the vowel contained in that syllable. As seen in Figure 2.8, we can classify

vowels in English according to whether they can appear in a stressed or unstressed

syllable.

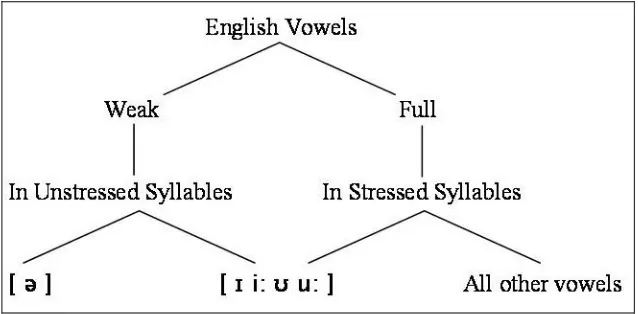

Figure 2.8 The Classification English vowel

Stressed syllables may contain any vowels except the schwa. The vowels of

unstressed syllables, however, are limited to the schwa, and the four high vowels.

offer, tolerate, but the four high vowels [ɪ, i:, ʊ, and u: ] may occur in either a

stressed or unstressed syllable as in eleven - confident, phonemic- phoneme,

cushion- duration, and conclusion – residue.

e. Lexical Stress and Lexical Category

Laver (1994: 511) defines lexical stress or word stress as “the placement

of phonological stress on a particular syllable within a word as a defining property

of that word.” Thus, lexical stress refers to the opposition of stressed and

unstressed syllables within polysyllabic words. English words have lexical stress.

That is, one or more of the syllables will have some combination of higher pitch,

greater loudness, or a less reduced vowel, when compared with the other syllables

in the word. According to Giegerich (1992), regularities that govern the lexical

stress placement depend to some extent on non-phonological information.

Syntactic or Lexical Category of words also provides guidelines for stress

placement. There are some general rules which may be useful to predict the stress

placement. The rules being general, sometimes, they are not fully applicable.

These general stress rules still depend crucially on the weight of the syllable

(McMahon, 2002).

According to Giegerich (1992: 190), “every word in English has a

(relatively) stable stress pattern, which is very little influenced by the context in

which the word occurs.” What is more notable is that stress is only assigned in

lexical words such as noun, verb, adjective and adverb. Function words do not

normally bear stress. Verbs and adjectives tend to have final stress. Meanwhile,

f. Stress Placement

Some people are probably more familiar with the terms initial stress to

refer to stress at the beginning of a word, but in phonology normally the number

of syllable in a word is counted from the back. Giegerich (1992) classifies stress

placement into either final or non-final.

Stress in polysyllabic words is often problematic. However, we have some

regularity which can help us predict the stress placement in words. Final stress or

ultimate stress is marked in English (Giegerich, 1992). It means that we can

predict whether a word can receive final stress. Syllable weight requirement

makes us possible to do so. A final-stressed syllable is only possible when the

word ends with a heavy syllable. Thus, there are no final-stressed words in

English that end in a light syllable.

Although a final stress is only possible when a word ends in a heavy

syllable, not all heavy syllables at the end of word are assigned with a stress.

There is no such a rule that a heavy final syllable must be assigned with a stress

because stress in English is not always predictable. A word may not have a final

stress although it ends in a heavy syllable. In the words utensil and discipline, we

notice the final heavy syllables. Yet, the final syllables in the two words are not

stressed. The word u'tensil bears the stress on the penultimate syllable, that is, the

second syllable from the last and the stress in the word 'discipline falls on the

antepenultimate, that is, the third syllable from last. Such patterns are common

with nouns, which will be discussed in the next section. The common stress

antepenultimate. Stress which falls further than antepenultimate is not frequent in

English (Giegerich, 1992).

g. Stress Rules in English

In English, stress placement is not entirely random. As we have seen,

nouns, for instance, are normally stressed on the penultimate or the

antepenultimate depending on the weight of the penultimate. In other words, we

can say that to a certain degree, stress is phonologically conditioned. Later on the

next section, we shall also find that stress can be morphologically conditioned.

The stress assignment rules, however, involve morphological processes,

such as affixation. In the following, we will discuss briefly six phonological rules

of stress assignments which are applicable in English, namely the Main Stress

Rules (MSR), the Long Vowel Stressing (LVS), Alternating Stress Rule (ASR),

Early Stress Requirement (ESR), Derivational Secondary Stress (DSS) and Stress

Clash Avoidance (SCA).

According to the Main Stress Rules (MSR), there are two the general rules

of primary stress assignment in Standard English, i.e. Pattern A (Noun Pattern)

and Pattern B (Verb Pattern) (Katamba, 1989; Hayes, 1995; Roca and Johnson,

1999 and McMahon, 2002 among others). The rules are the most general guide of

the stress patterns in English. They can be a good help when we deal with

unfamiliar words, especially of two syllable length.

Pattern A applies to nouns and suffixed adjectives. Polysyllabic nouns and

suffixed are stressed on the penultimate syllable if the penult is heavy. For

examples, the words 'elbow, a'ttractive, a'roma and a'genda are stressed have

stress is assigned to the antepenultimate as in the example 'syllable, 'difficult and

'discipline.

Pattern B applies to Verbs and unsuffixed adjectives. The stress in

polysyllabic verbs falls on the ultimate or final syllable if the syllable is heavy, as

in a'gree, con'clude o'bey and a'tone. If the final syllable is light, the stress is

given to the penultimate syllable, for instance re'member, 'tally and 'hurry.

The second rule is called Long Vowel Stressing (LVS). The presence of a

long vowel in a final syllable makes the syllable heavy and therefore is stressable.

Long Vowel Stressing “assigns foot status to final syllable containing a long

vowel (Hogg, 1987: 115). Thus, the ultimate syllable with a long vowel may

attract stress, e.g. balloon and delay.

The third rule is Alternating Stress Rule (ASR). Alternating stress rule is

phonological rule proposed by Chomsky & Halle (1968) which assigns primary

lexical stress to the antepenutimate syllable of words where the main stress rule

has assigned primary stress to the final syllable. The rule only applies to

polysyllabic verbs. For polysyllabic verbs, the application of MSR, which assign

the stress on the ultimate syllable, becomes unfavorable. The ultimate stress then

moves to the antepenultimate syllable, e.g. decorate. The final primary stress is

reduced by the rule to a secondary stress. Thus, the output of the main stress rule

for the word decorate is [decəˈreɪt]. The alternating stress rule converts this to

[ˈdecəreɪt].

The fourth rules is Early Stress Requirement (ESR). For polysyllabic

words, major stress falls on one of the first two syllables. For example, the word

quite rare to have primary stress falling further than the antepenult. The stress

pattern of suprasegmental, for instance, can be indicated with numbers as 20310,

with accents as ˌsuprasegˈmental, or, using an IPA transcription, as

/ˌsu:prəsegˈmentl/.

On the basis of the examples above, we can see some of the general

properties of English word stress. First, primary stress does not normally fall

further than antepenult. It suggests that primary stress is always the rightmost

major stress, i.e., the last rhythmic beat is the strongest. This is what we call

prominence of the right edge. Second, there are no English words starting with

two successive zero-or tertiary stressed syllables. One of the first two syllables of

a word must be prominent (i.e., primary or secondary stressed). This is known as

the prominence of the left edge, or, as sometimes it is referred to, the Early Stress

Requirement. For polysyllabic words, the Early Stress Requirement is the result of

which, in longer words, if primary stress falls on no further than antepenultimate

syllable, the first or the second syllable must be assigned secondary stress.

The next rule is Derivational Secondary Stress (DSS). In derived words,

since suffixation has made the word longer, primary stress often shifts to the right,

and the original primary stress is then reduced to secondary. In such derived

words the rhythmic prominence of the original stress pattern is preserved. This

secondary stress is frequently referred to as Derivational Secondary Stress. In the

word 'educate, for example, primary stress falls on the first syllable, which

reduces to secondary stress when ˌedu'cation is derived. If a suffix is attached to a

long word which already contains a secondary stress, further secondary stresses

The last rule is Stress Clash Avoidance (SCA). The rule disallows a

secondary stress to appear immediately preceding the primary stress (Goldsmith,

1996). In an English word without an internal word boundary, major stresses may

not fall on adjacent syllable. Stress clash avoidance often accompanies the

affixation process. For example in the word de'rive the primary stress falls on the

final syllable as governed by Pattern B of MSR. When the suffix –ation is added

to the word, the primary stress of the original is not retained. Instead, it is shifted

to the left and is reduced to secondary. Therefore, the result is ˌderi'vation and not

*de'ri'vation or *deˌri'vation.

3. Morphological Processes

A word may come into existence in a particular language through many

different ways. The processes which take place in the formation of new word is

called morphological processes. There are various kinds of morphological

processes, for examples affixation, conversion, compounding, borrowing,

compounding, backformation, clipping, blends, acronyms, clipping, cliticization,

suppletion, reduplication and coinage. In English, as in many other languages,

stress interacts with morphology (McMahon, 2002), so that morphological

processes such as affixation and compounding may cause stress shift. Let us now

discuss some relevant morphological processes.

a. Affixation

Affixation is the process of adding an affix. In general, the classification of

affixes falls into two categories, namely inflectional and derivational affixes. An

syntactic function to which it belongs (O’Grady, Dobrovolsky & Katamba, 1996).

In contrast, a derivational affix is attached to its base to derive new words by

either changing the meaning or the category. Based on the position they are

attached to, we can distinguish affixes into prefix, which is attached to the front of

its base, infixes, which occurs within its base, and suffixes, which is attached to

the end of its base.

Affixation may trigger stress changes. Derivational prefixes normally do

not influence stress placement. Some derivational suffixes, however, result in

stress shifts. Therefore, on phonological side, derivational suffixes are divided

into two classes, namely stress-neutral and stress-shifting suffixes (Stockwell and

Minkova, 2001) The number of stress-shifting suffixes is relatively smaller than

that of stress-neutral. Some examples of stress-neutral are –ant, ly, and –ness as in

as'sist - as'sistant, 'happy – 'happily, and 'friendly – 'friendliness. Some

stress-shifting suffixes are –ation, -ic, and –ity, as found in in'vite -invi'tation, 'symbol -

sym'bolic, and 'possible – possi'bility.

b. Conversion

Conversion is a process of assigning an already existing word to a new

syntactic category without any affixation process. In other words, it is a process of

deriving one lexeme from another by means of phonologically empty or zero affix

(Carstairs McCarthy, 2002) For this reason, it is also called Zero-Derivation. With

only a few exceptions, conversion is usually restricted to monomorphemic words

(O’Grady, et al., 1996). Some examples of conversion are ship (noun to verb), dry

According to Stockwell and Minkova (2001), conversions that have

already existed long enough in a language are usually presented in as a single

entry in the dictionary. Such conversions are often semantically close in meaning.

However, new conversions, they add, tend to appear as separate entries in

dictionary. Being listed as separate entries may also indicate that they are not

closely related in meaning.

c. Compounding

Another morphological process which can trigger stress shift is

Compounding. Compounding is the process of combining two or more words to

form a new word. Compounding can take place within any classes of word (Quirk

et al., 1985). If standing as individual words, both elements bear a primary stress.

Yet, in the process of compounding, the only one element will retain the primary

stress and the other element will receive secondary stress. For example, both the

words black and board bear primary stress since they are content words.

However, in the compound word blackboard, only the first element has the

primary stress; the primary stress of second element is reduced into secondary.

Stockwell and Minkova (2001) argue that compounding is the largest and

the most important source of new words. They also classify compounds into

syntactic compound and lexical compounds. A syntactic compound is one which

is formed by rules of grammar, for example shoemaker. They are normally not

listed in a dictionary. A lexical compound is one which results in new meaning

which has to be checked in the dictionary if we do not know the meaning, for

d. Backformation

A word may be created by removing a real or supposed affix of an already

existing word. The deletion may be the result of “an incorrect morphological

analysis” (Fromkin, Blair & Collins, 2000: 83). A new word may enter the

language as a result of an incorrect morphological analysis. Such ignorance shows

creativity of speakers. For instance, the word editor appeared before the verb (to)

edit. The -or ending of the word editor was mistakenly analyzed as derivational

suffix -or, involving the notion of agent, which was attached to verb (to) edit.

Other examples are verbs ending in –ate, e.g. narrate and donate which were

derived from the nouns ending in –ion, i.e. narration and donation.

e. Borrowing

Another important source of new words is borrowing from other

languages. In this process, one language may take words or lexemes from other

language to be added to its lexicon. The new words are called loan words or

borrowings. Both terms are not really appropriate because in reality the receiving

language never gives the words back to the origin (Crystal, 1995). Borrowings are

one of the results of language contacts (O’Grady et al., 1996). It happens when

people from different cultures and different languages make contact. For this

reason, word origin also may significant role in stress placement. Native words

and early French adoption tend to have primary stress on the stem syllable

regardless of the affixes added to them (Quirk et al., 1985). By contrast, with

more recent adoptions and with derivational processes, the place of the stress

Borrowing may take place directly or indirectly (Fromkin & Rodman,

1988). A direct borrowing happens when a lexical item of one language is directly

taken by another language to be added to its lexicon. The word ballet in English,

for example, is a result of direct borrowing from French. On the other hand, an

indirect borrowing happens when a lexical item of one language has been

borrowed into another language and in turn is borrowed by another language. The

English word restaurant is an example of indirect borrowing from Latin. The

Latin word restaurare was first borrowed into French and in turns English

borrowed the word from French.

4. Origin of English Vocabulary

English is part of the Germanic group of language, and is descended from

the language known as proto-Germanic which developed around the same time as

Latin and whose speakers settled in North-West Europe after the dispersion of the

Indo-Europeans between 4000 and 3000 BC. English owes it existence to a

number of languages, including Latin, Britanic, Anglo-Saxon, Old Norse and

French (Stockwell and Minkova, 2001). Latin is the language of the Romans and

also the language of Christianity; and Britannic is the language of the Celtic

people living in Britain prior to the Roman invasions. The language survives

today in Welsh and Breton. Anglo-Saxon, or Old English is the language of the

Germanic peoples who invaded Britain after the Roman garrisons. Old Norse is

the language of the Vikings; and French is the language of the Normans.

Let us now discuss how those languages brought about changes up

a. Anglo-Saxon Bases

Modern English has its roots in the Germanic language called

Anglo-Saxon or Old English. In AD 449 a group of Germanic invaders arrived in Britain.

The Germanic invaders, who were not very literate, settled in such a great

numbers. Therefore, it was not surprising that the original Anglo-Saxon lexicon is

concerned about basic, down-to-earth matters. Many of the words are still used

today. Some are grammatical words, such as be, in, that, while others are lexical

words such as live, sing, and weep, go. As we notice, Anglo-Saxon words are

usually short.

According to Crystal (1995) and (Stevenson, 1983), although

Anglo-Saxon lexemes are relatively small in number, in any passage of English, they are

frequently used. Many of those words become the core vocabulary of English

today. There words are, for examples, parts of body e.g. ear, eye, arm, foot,

natural environment e.g. land, hill, field wood, domestic life e.g. home, house,

door, animals, e.g. cow, dog, fish, goat, sheep, common adjective, e.g. dark,

black, food, long and common verbs e.g. become, eat, do, go, sleep, love.

b. Celtic Borrowings

Celtic is the language of the original inhabitants of Britain before the

Roman invasions around 55 BC to 410. The Roman did not impose their

language, Latin, to the local people. Therefore, people there remained

Celtic-speaking until the invasions of the Anglo-Saxons in 499 AD. The arrival the

Anglo-Saxon displaced the original inhabitants, causing them to move to the

northern and western fringes of the island. Up to now, in those places, Celtic

the Anglo-Saxon speakers. Those who still lived in the other parts of Britain

merged with the Anglo-Saxons. The end result is a small number of Celtic

borrowings. The primary influence of the Celtic language which remains until

today was in names of rivers, for examples avon and ouse, and parts of name of

place, such as -hamm, and -combe (Stockwell & Minkova, 2001).

c. Latin Borrowings

Latin is the Language of the Roman Empire. “Latin has been a major

influence on English through out it history (Crystal, 1995: 8).” The Anglo-Saxons

probably had known some Latin even before they came to Britain. Latin was also

the language of Christianity “The most significant influence of Latin on English

comes through the adoption of Christianity by the Anglo-Saxons” (Stockwell and

Minkova, 2001: 32). In AD 597 St Augustine landed in Kent to convert the

Anglo-Saxons. First, a large number of religious terms were imported, such as

candle, devil, priest, angel, disciple and martyr. Through the increase of literacy

of the Anglo-Saxons, many more learned Latin words entered the language, e.g.

alphabet, describe, discuss and history. By the end of the Renaissance, the size of

the words derived from Latin had doubled.

d. Scandinavian Borrowings

The next great influence on the development of English was the Viking

invasions which took place between AD 750 and 1050. The influence of the

Scandinavian on Britain can be thought of in terms of three periods. Firstly,

during the period of 750 - 1016, the Vikings (Scandinavian) began attacking the

northern and eastern shores of Britain and settling in those parts of Britain. The

borrowing took place. The early borrowing fro Scandinavians include husbonda

(husband) and lagu (law). Secondly, during the period of 1016-1050, the

condition was more or less similar to the earlier period, only that King Alfred the

Great had succeeded in uniting the Anglo-Saxons and in promoting the English

Language. There were more borrowing at that time, including cnif (knife).

Finally, more borrowing took place in the period of 1050 onward, even

during the Norman invasions (Stockwell & Minkova, 2001). This happened

because both the Anglo-Saxons and Scandinavians were subdued by the Norman.

Naturally, they lived together and interact with each other; therefore, there was a

massive influence of the Scandinavians on English. It is difficult to identify the

Scandinavian loan words because Scandinavian and Anglo-Saxon exhibit great

similarity. The Scandinavian borrowings include common words such as bag,

give, die, skin, dirt and smile. The end result of the Viking invasions alone are

about 2000 Scandinavian words borrowed into English (Crystal, 1995).

e. French Borrowings

The enormous effect of the Norman Conquest of 1066 on the vocabulary

of English is in the political and social standing of the conquerors (Crystal, 1995).

When the Norman took over England, they changed the language of the

government and court. French was the language of the Norman aristocracy and

therefore also the language of prestige while English was the language of the

common folk. There were three periods of French borrowings, i.e. borrowing

during the colonization (1066-1204), early post conquest borrowing (1250-1400),

During the colonization, there were not many French borrowing, since

English continued to be used largely in its own, low-level social class, and French

and English were kept separate (Stevenson, 1983). The borrowing only took place

when the Norman lower social class, crossing the social class, made contact with

the English. Up to 1250, many of the loanwords were ones that the lower class

was familiar with through the contact with French-speaking nobility, e.g. baron,

noble, dame, servant and messenger. The period after the Norman Conquest, in

the middle of the thirtieth century, is considered as the period of shifting emphasis

on the two languages spoken in England (Stockwell & Minkova, 2001, and

Veniranda, 2001). Upper classes were gradually starting to use English.

Consequently, the number of French loanwords increased dramatically. It

happened partly because of the enormous number of intermarriage with English

people (Crystal, 1995).

The third period of French borrowing is from around 1400 onwards. At

that time, English regained it status to become the dominant language (Stockwell

& Minkova, 2001). The experience of borrowing Norman French vocabulary into

English proved English as a tolerant language. Therefore, it was easy for English

to borrow more words from Central French or Parisian French which was

considered more prestigious than the Norman French. Beginning on the 16th, the

advancement of printing was making the spread of learning. A lot of books

appeared, mostly in Latin but some are French. This triggered more borrowing of

French. The new loanwords from French are usually specific in meaning, related

B. Previous Research

Variation in stress placement also occurs between Standard British (BE)

and other varieties of English. The following are two studies which have looked at

these phenomena. The first is the difference between British and Singapore

English, and the second is variation which occurs in British and American

English.

1. Ling and Grabe’s Study on British and Singapore English

The first research was conducted by Low Ee Ling and Esther Grabe (2001)

on Contrastive study of prosody and lexical stress placement in Singapore English

and British English. They questioned the claim that Singapore English and British

English differ in stress placement. It is said that Singapore English speakers stress

the final syllables of polysyllabic words, which are stressed initially in British

English. Ling and Grabe (2001) hypothesized that it is not the location of lexical

stress which differs in the two varieties, but the acoustic realization of the stress.

They conducted an experiment. Ten Singapore English and ten British English

speakers were asked to produce polysyllabic words and the duration

measurements were taken. The results did not support the claim. Besides, they

found that the difference between the nuclear syllable and the following

unstressed syllables is less clearly marked.

2. Berg’s Study on British and American English

While the previous study relied on the experiment to prove the claim, the

second study conducted by Thomas Berg (1999) relied on a dictionary to gather

and American English. A comparison of the pronunciation of all 75,000 entries in

Well’s Dictionary yielded 932 stress-divergent words. There are three important

findings. First, the shorter the words, the lower the ratio between the

stress-divergent words and same-stress words in the dictionary lower, and the other way

around. Thus, longer words tend to trigger stress variation than shorter words.

Second, main stress falls further to the left in British than in American English.

Third, suffixes which play a variable role in the stress assignment process include

[-ate], [-ess], [-ive], [-ly], and [-ory].

Berg’s research is quite comprehensive in terms of data. However, I note

some important points from his analysis. Firstly, he used length, the number of

syllables in words, as the basis of the classification of the data. He did not classify

the data based on the part of speech of the words. Second, the difference of stress

assignment was compared on the basis of direction. By this, he could

over-generalize the stress difference that in BE stress tends to fall further to the left and

AE to the right; and this did not show specific characteristics of each part of

speech of the words. Finally, he did prove that such variation occurred, yet he did

not explain how it occurred.

C. Theoretical Framework

British and American English are the major different varieties of English.

Quirk et al. (1985) argue that grammatical, particularly syntactic, differences are

few, but lexical differences are far numerous. In general British and American