THE LEXICAL DIFFERENCES IN MADURESE VARIETIES

SPOKEN BY PEOPLE IN SITUBONDO REGENCY

A THESIS

Submitted as Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements

For Sarjana Degree of English Departement Faculty of Humanities Universitas Airlangga Surabaya

Rhofiatul Badriyah

121211231127

ENGLISH DEPARTMENT

FACULTY OF HUMANITIES

UNIVERSITAS AIRLANGGA

SURABAYA

I dedicate this thesis to Allah SWT, my parents,

younger brother, family, and friends.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

First of all, I would like to thank Allah SWT who always gives me all I need to live and to finish this thesis. Thank you for always giving me patience, strength, spirit to accomplish my biggest goal in bachelor degree.

This t hesis w ould ne ver be a ccomplished w ithout t he g uidance of m y thesis advisor, Erlita Rusnaningtias, M.A. From the bottom of my heart, I would like t o t hank you for your p atience, ki ndness, m otivation, t ime, s pirit, a nd knowledge. I am f eeling s o bl essed t o h ave you a s m y t hesis a dvisor. Also I extend m y g ratitudes to a ll le cturers o f E nglish D epartment o f U niversitas Airlangga for giving me knowledge during my college time.

I also want to thank to my beloved parents who always support me. Thank you for all the things you have done for me. Thank you for always being my eyes when I am in t he da rk. T o m y younger br other, t hank you f or be ing m y moodbooster whenever I feel so unmotivated.

Finally, I want to say thank you to m y second family, Annishah, DBSK (Dita, S hovi, K hotim), Tita, T eteh, D essy, D eivy, Faras, Zahratum, S heila, a nd Made F , Nova, R indra, a nd m y bo arding ho use f riends (Fitri, A ni, M bak Husnul,Vitta, Zafira, Din, and Bety) for being special persons I could depend on. Thank you for everything.

14th June 2016

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Title Page ……….. i

Inside Title Page ………... ii

Declaration Page ……….. iii

Dedication Page ……… iv

Thesis Advisor’s Approval Page ……….. v

Thesis Examiner’s Approval Page ……… vi

Acknowledgement ……… vii

Table of Contents ……….. viii

Abstract ………. ix

CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION ……….. 1

1.1Background of the Study ……… 1

1.2Statement of the Problem ………... 6

1.3Objective of the Study ……… 6

1.4Significance of the Study ……… 7

1.5Definition of Key Terms ……… 7

CHAPTER II LITERATURE REVIEW ……….. 9

2.1 Related Theories ………. 9

2.2 Related Studies ………19

CHAPTER III METHOD OF THE STUDY ………... 22

3.1 Study Approach ……….. 22

3.2 Location of the Study ………. 22

3.3. Population and Sample ………. 25

3.4 Instrument of the Study ……….. 26

3.5 Technic of Data Collection ………. 27

3.6 Technic of Data Analysis ……… 28

Rhofiatul Badriyah.2016. The Lexical Differences in Madurese Varieties Spoken by

People in Situbondo Regency. English Department Faculty of Humanities Universitas Airlangga.

Abstract

One of the characteristics of Madurese variety used in Situbondo Regency is the lexical differences. Focusing on the Madurese variety used by people to communicate in daily life, this study aimed to describe the lexical differences and to reveal the status of the lexical differences. Five villages were chosen as the observation points of the study: Demung (OP1), T anjung Pecinan ( OP2), Sumberwaru ( OP3), Curah T atal ( OP4), a nd Taman ( OP5). U sing a word l ist of 450 w ords, a t otal of fifteen informants w ere interviewed. Beside interview, some activities included recording, note taking, and cross-checking w ere a lso carried o ut to o btain t he d ata. The data were then analyzed an d calculated using dialectometry formula. The results show that out of 450, t here are 133 lexical d ifferences. The p ercentage of the l exical d ifferences b etween OP 1 s nd O P2 reaches 52. 6% which means that the varieties used in the two OPs are different dialects. Meanwhile, index percentage in six other compared OPs indicates that they have different sub-dialect status. The percentage of the lexical differences between OP 2 and OP3 is 42. 1%, OP3 and OP4 is 42. 1%, OP4 and OP5 is 45. 9%, OP1 and OP5 is 34. 6%, OP2 and OP5 is 40. 6%, a nd OP2 and OP5 is 42. 9 %. I n c onclusion, the s tatus of the l exical differences of the Madurese varieties spoken by people in Situbondo Regency includes different dialects and different subdialects.

Keywords: Geographical dialect, Lexical differences, Madurese Variety, Situbondo, Synchronic Study

CHAPTER I

INTRODUCTION

1.1Background of the Study

The name Madura refers to an Island which is part of East Java Province

but separated b y a narrow strait of Madura. It has four big regencies which are

Bangkalan, S ampang, P amekasan, and S umenep. Contrary t o people i n m ost

regions in East Java Province who use Javanese as their local language, people in

Madura use Madurese as their daily language. Lauder (cited in Sofyan, 2010, p.

207) s tated t hat Madurese l anguage b ecomes the f ourth l argest l anguage i n

Indonesia which is spoken by almost 14 million people.

Based on l inguistic aspect, Madurese language i s divided into four main

dialects: Bangkalan, Kangean, Pamekasan, and Sumenep dialect (Sofyan, 2010, p.

208). T hose f our di alects a re us ed i n di fferent r egions i n M adura lsland.

According to Zainuddin et al. and Wibisono et al. (cited in Sofyan, 2010, p. 208),

Bangkalan dialect is used in Sampang and Bangkalan. Kangean dialect is used in

Kangean Island e ven t hough t his i sland i s pa rt of S umenep r egency (Sofyan,

2010, p. 216) . T he ot her di alect, P amekasan di alect, is us ed i n w estern part of

Sumenep and Pamekasan regency. The last dialect, Sumenep dialect is spoken by

people in Sumenep regency, except some areas which are adjacent to Pamekasan

Similar to Javanese language, the speech level of Madurese is divided into

three levels. The highest level is engghi bhunten which is used to address older

people. The second level is engghi enten which is spoken by people in the same

age. T he t hird l evel, enja’ i ya is us ually used by p eople t o s peak t o younger

speaker. As an example, i n engghi bunt en, people s ay adha’ar [adhǝ’ǝr] for ‘eating’ an d mostaka [mɔstaka] for ‘h ead’. In engghi e nten, people s ay neddha

[nǝddha] for ‘eating’ and sera [sɛra] for ‘head,’ while in enja’ iya level, people say ngakan [ŋakan] for ‘eating’ and cethak [tʃɛtak] for ‘head’.

Talking about t he po pulation, M adurese e thnic gr oup w as greatly

increasing by surpassing 4. 3 m illion people in 2000, coming as the third biggest

ethnic group after Javanese and Sundanese (Syamsuddin, 2007, p. 162) . Related

to t he l anguage t hey u se e very da y, i t i s qui te i nteresting t o know how f ar

Madurese language extends in society. Madurese language is not only spoken by

people in Madura Island. It might be due to the fact that Madurese ethnic group

also l ives i n ot her r egions i n Indonesia. S utoko, S oegianto, a nd S urani (1998)

stated that some regencies outside Madura Island are also occupied by Madurese

ethnic group, such as Pasuruan, Probolinggo, Bondowoso, Jember, and Situbondo

which are located in eastern part of East Java Province. Moreover, there are some

areas in Surabaya, Banyuwangi, and Bali whose people also speak in Madurese

(Sutoko, e t a l., 1998) . Therefore, Madurese p eople also have t heir o wn p lace

outside Madura Island, especially in eastern part of East Java.

Moving t o J ava Island, particularly to East J ava Province, this pr ovince

Madurese people leave their island and move to Java Island (Syamsuddin, 2007,

p. 63). It results in a massive migration to the eastern part of East Java Province

which happened in 19th century and it is proven by the fact that the population of

Madurese ethnic group in this area reached about 500.000 inhabitants at that time

(Syamsuddin, 2007, p. 163).

There are some r easons w hy M adurese pe ople tend t o m igrate t o ot her

regions. A s s tated b y Lee ( cited i n H artono, 2 010, p. 3) , t here a re f our m ain

factors influencing M adurese people t o m igrate. T hey are (1) factors associated

with th e a rea o f o rigin, ( 2) factors a ssociated with th e a rea o f d estination, ( 3)

intervening obs tacles, a nd ( 4) pe rsonal f actors. P overty which happened in 19th century was considered the main reason for Madurese people to migrate to Java

Island. 63% of Madurese people worked as farmers, but unfertile soil became the

biggest problem which brought them to the difficulty in fulfilling the demand of

staple (Kuntowijoyo cited in Hartono, 2010, p. 4).

Some regencies in eastern part of East Java Province that become the main

destination of Madurese people are known as Tapal Kuda area (Sutarto, 2006, p.

1). The term Tapal Kuda is derived from the form of this area that looks like a

horseshoe. T he s ociety here i s know n as pandalungan. T he t erm pandalungan

emerges as the result of two dominant cultures, Madurese and Javanese that blend

and create a new culture (Sutarto, 2006, p. 1). According to Prawiroatmodjo (cited

in S utarto, 2006, p. 2 ), t he t erm pandhalungan means speaking to others

dominant e thnic groups, M adurese a nd J avanese, ha ve t heir ow n characteristics

(Kusnadi cited in Sutarto, 2006, p. 4).

Madurese people consider Tapal Kuda area as their second home, a place

where they work and earn money. The main linguistic characteristic found in this

area i s t he u se o f enja’ i ya or ngoko speech level b y m ixing t wo or m ore

languages to communicate with other people (Sutarto, 2006, p. 2). The spread of

Madurese people in Tapal Kuda area varies. Madurese people tend to migrate to

different regencies in East Java Province. People from Sampang mostly migrate to

Pasuruan a nd P robolinggo, people f rom P amekasan t end t o m igrate t o Jember,

while pe ople from Sumenep t end t o m igrate t o B ondowoso a nd S itubondo

(Syamsuddin, 2007, p. 167). Thus, even though people in some of the regencies in

Tapal Kuda area u se Madurese l anguage, their la nguage is a ssumed to b e

influenced by different varieties of Madurese language.

Regarding Madurese va riety i n S itubondo, pe ople i n t his r egency us e

mutual in telligibility in understanding v arieties used i n di fferent s ub-disctricts.

For example, people in the western part say kowek [kɔwɜk] that refers to ‘owl,’

the northern part say sengghik [sɛŋghIɁ] that refers to ‘crab,’ while people in the

southern say kopeteng [kɔpɛtɛŋ].

Based on t he phonemenon f ound i n t he us e of Madurese variety i n

Situbondo, t his s tudy i s c onducted ba sed on t hree a ssumptions. ( 1) T he variety

used in Situbondo is assumed to be influenced by Sumenep dialect. It m ight be

because m ost of S umenep pe ople chose t o m igrate t o S itubondo i nstead of t o

other regencies in Tapal Kuda area. (2) The second assumption is the possibility

of pe ople i n S itubondo r egency t o s peak di fferent varieties. T his a ssumption

emerges due to the lack of mutual intelligibility faced by people in their daily life.

(3) The last assumption is the lack of mutual intelligibility which is faced by the

people m ight be be cause of the l ocation of Situbondo which is a djacent to

Probolinggo, a regency where most of Sampang people migrated to. Probolinggo

is near the border line of the western part of Situbondo Regency which leads to

the assumption t hat pe ople i n the western pa rt of S itubondo i nteract m ore w ith

people f rom P robolinggo. It results in the p ossibility that the v ariety used b y

people i n the western pa rt of S itubondo is influenced b y the variety used i n

Probolinggo Regency. Moreover, the distance from the western part to the central

town of Situbondo is quite far, which is about 25 km.

Some studies focusing on Madurese v arieties have be en conducted.

Awaliyah ( 2015) w ho c onducted a study f ocusing o n l exical d ifferences i n

Kangean Island, S umenep Regency used 4 50 lexical ite ms b y carrying out

interviews with l ocal pe ople in Kangean Island. T he result of t his s tudy is the

is different from my study because I analysed the lexical differences in Situbondo

Regency which was located in Tapal Kuda area.

Another study was pe rformed b y Asyatun (2005). She studied about t he

isolect stratigraphy o f M adurese language spoken b y p eople i n P amekasan

Regency. This synchronic study tried to compare 233 g losses in seven OP(s) to

find t he l exical d ifferences. T his study i s di fferent f rom m y s tudy be cause s he

analysed M adurese v ariety i n P amekasan Regency, while m y s tudy focused on

Madurese variety in Situbondo regency. The last study came from Tri (2015) who

studied a bout P andhalungan l anguage i n P robolinggo w hich f ocused on bot h

phonological and l exical di fferences b y us ing 2 00 w ords. T his s tudy a nalysed

both Madurese and Javanese language that were used by people to communicate

in every day conversation. It is different from my study. In her study, Tri focused

on p honological a nd l exical as pects o f M adurese an d J avanese l anguage i n

Probolinggo Regency. Meanwhile, my study only focused on lexical differences

in Madurese variety in Situbondo Regency.

1.2Statement of the Problems

Based on t he b ackground of t he s tudy, t he problems in th is s tudy a re

formulated as follow:

1. What ar e t he l exical d ifferences found i n t he M adurese va riety used b y

people in Situbondo Regency?

2. What is the status of those lexical differences?

Based on the statements of the problem, the objectives of the study are as

follow:

1. To identify the lexical differences found in the Madurese variety used by

people in Situbondo Regency.

2. To determine the status of those lexical differences.

1.4 Significance of the Study

This study is expected to give theoretical and practical contributions. For

the t heoretical c ontribution, t his s tudy m ight s trengthen t he de velopment of

dialectology s tudy. B eside t hat, t his study i s e xpected t o give i nsights t o f uture

dialectology s tudies. It could also be u sed as a refenrence for t he n ext

dialectologists who want to conduct study about Madurese language, especially in

Situbondo Regency. S ince t his s tudy onl y focuses on s ynchronic approach, i t

might he lp f uture s tudies which ex plores M adurese v ariety using di achronic

approach. For students, this study is expected to give new insight about Madurese

varieties outside Madura Island, such as in Situbondo.

For pr actical c ontribution, t his s tudy m ight give c lear di fferences f or

Situbondo pe ople a bout t he va riety us ed i n t heir da ily l ife s o t hey kno w m ore

about their own variety. For the local government of Situbondo Regency, it might

be us eful to i ntroduce Situbondo a s a part of Tapal K uda area w ith i ts o wn

linguistic characteristics contrasting to the other areas.

• Dialect : a subdivision of a particular language or a variety

which i s g rammatically (and p erhaps l exically) as

well a s phonol ogically different f rom ot her

varieties (Chambers and Trudgill, 2004, p. 3-5)

• Synchronic study : a study th at d eals w ith lin guistic f eatures or

events in a particular time (Mahsun, 2005, p. 84)

• Geographical dialect : a dialect in w hich various lin guistic d ifferences

accumulated in a p articular geographic r egion

(Chambers and Trudgill, 2004, p. 5).

• Lexical differences : the differences of words used by different speaker

to poi nt out s ame obj ect ( Chambers a nd T rudgill,

CHAPTER II

LITERATURE REVIEW

This chapter reviews some theories related to the main concepts used i n

the s tudy of di alectology a nd used as t he guidance f or s tudying the lexical

differences found i n t he M adurese v ariety us ed i n Situbondo Regency. This

chapter also describes some previous studies which have been conducted to study

the Madurese variety and which are related to this study.

2.1 Related Theories

2.1.1 Language, Dialect, Accent, and Variety.

The t erm l anguage, d ialect, ac cent an d v ariety a re r elated t o ea ch o ther.

Talking about language, it is not just dealing with linguistic aspects since there are

so m any considerations l ay be hind i t, s uch a s pol itical, geographical, hi storical,

and sociological aspects (Chambers and Trudgill, 2004, p. 4) . The term language

is used for variety which has standardized its own grammar, orthographies, and

books, a nd that is usually di fferent f rom one a nother, s uch a s B ritish a nd

American E nglish w hich ar e considered d ifferent l anguages (Chambers a nd

Trudgill, 200 4, p. 4) . B ritish people us e flat as t he s tandard form whereas

American people use apartment to refer t o t he s ame bui lding. T alking a bout

language, it cannot be separated from dialect. A language contains some dialects

which often hardly to be understood by the speakers. According to Chambers and

Trudgill (2004, p. 3), dialect is a subdivision of a language which shows the

working class and low society. More particular, dialect is a collection of different

grammatical, phonological, and lexical aspects of particular language (Chambers

and T rudgill, 2004, p. 5) . T he e xample is taken f rom S cot pe ople t hat pr efer

considered a language or a dialect. Considering the phenomenon, the term variety

could be applied to those undefined forms. The term variety is used as the neutral

term t hat c ould be f ound i n t he l evel of speech, di alect, or e ven l anguage

(Chamber & Trudgill, 2004, p. 5).

2.1.2 Types of Dialect

According to Chamber and Trudgill (2004), there are two types of dialect

which are social and geographical dialect. Social dialect emerges as the result of

different aspects i n s ociety, s uch a s t he de gree of e ducation, oc cupation, a nd

family status which means that social dialect is put towards the people based on

how they are treated or respected in society (Holmes, 2004, p. 139) . Bankers do

not talk like office cleaner and teachers do not talk in the same way like a security

guard. It can be seen from the example in England where people who belong to

the u pper cl ass i s lavatory instead o f toilet. S ocial c lass a lso s hapes on how

people pronounce some words. The study which was conducted by Labov (cited

in H olmes, 2004, p. 14 5) s howed a clear s ocial s tratification w here p eople a t

prestigious s tore us ed post-vocalic [ r] c onsistently t han pe ople w ho vi sited

standard stores. Another example comes from New York where the use of

post-vocalic [ r] i s c onsidered more prestigious. It means that the h igher someone

belongs to a social group, the more use of post-vocalic [r] (Holmes, 2004, p. 145).

Geographical dialect refers to the dialect differences due to geographical

aspects ( Chambers a nd T rudgill, 2004, p. 5) . In s ociolinguistics, t he t erm

geographical d ialect r efers t o r egional va riation w hich i s f ocusing on r egional

differences. The differences in regional variation here can be found in the level of

accent, dialect, or even language, such as American and British English that are

considered different languages (Holmes, 2008, p. 128). For example, Americans

prefer do you have that seems uncommon to British people. Geographical dialect

is quite different from regional variation since geographical dialect is focusing on

the level of dialect where usually emerges only in one area, such as the differences

of A merican E nglish di alect us ed i n Boston a nd N ew Y ork ( Holmes, 2008, p.

131). Another example of geographical dialect is Cockney dialect in London with

its glottal stop [Ɂ] instead of [t] in words like bitter and butter (Holmes, 2004, p.

131).

This study is a synchronic r esearch which is different f rom di achronic

place and time while diachronic research focuses on language evolution or how a

particular language changes from time to time (Mahsun, 2005, p. 84).

2.1.3 Dialect Chain

In many parts of the world, linguistic differences distinguish one village

from a nother. Sometimes, it is f ound th at a d ialect spoken i n an A area is

understood well by people in B area while people in E area only understand few

words of A area and people in G area do not understand it at all. The differences

might be s maller or bigger, but t hey w ould be c umulative ( Chambers a nd

Trudgill, 2004, p. 5) . It depends on the distance that separates one village from

another. The greater the distance is, the greater the linguistics differences found. It

means that dialects on outer edges might not be mutually intelligible but they are

linked by the chain of mutual intelligibility (Chambers and Trudgill, 2004, p. 5).

The ex ample can be f ound i n S candinavian c hain. E ven t hough

Norwegian, S wedish, a nd D anish a re c onsidered di fferent l anguages, yet t he

Scandinavian chain that links dialects of those three languages make Swedes and

Norwegian i n bor der areas unde rstand e ach ot her t han S wedes i n s outhern a nd

northern a rea (Holmes, 2008, p. 135) . It i s di fferent from va rieties us ed b y

Chinese pe ople in C hina. E ven t hough Mandarin a nd C antonese are co nsidered

dialects of C hinese, the speakers o f t hose d ialects do not understand each ot her

(Holmes, 2008, p. 135) . It shows t he arbitrariness o f t he d ifferences b etween

language a nd d ialect. H owever, th e me asurement o f mu tual in telligible is o ften

understand D anes. It m ight be c aused b y s ome f actors, s uch as l istener’s

willingness to understand and their degree of education (Chambers and Trudgill,

2004, p. 4).

2.1.4 Dialect Features

Similar to language, a dialect also h as some l inguistic a spects, s uch a s

phonological, l exical, s yntactical, m orphological, a nd s emantic a spects. E ven

countries that use the same root language, such as American and British English

might have d ifferences t hat can be seen through those linguistics aspects.

Phonology deals w ith t he pa ttern a nd s ound o f particular l anguage, s pecifically

deals with how speech sounds form a system of our language (Fromkin, Rodman,

and Hyams, 2003, p. 273) . Meanwhile, phonological differences are focusing on

how words are pronounced differently from one area to the others. An example

can be ta ken f rom A merican and British E nglish. B ritish R P w ould u se /a :/ in

pronouncing clash while American would use /æ/ to pronounce the same word.

Meanwhile, a ccording t o Chambers a nd T rudgill ( 2003, p. 97) , l exical

differences r efer t o d ifferent w ords used b y di fferent s peakers to poi nt out the

same object. As an example, the term dutch cheese is used in northeastern region

of North America; whereas, cottage cheese is used by American midland people,

but brose is used in Scotland.

Another aspect, s yntactical aspect i s defined as rules of grammar w hich

(Fromkin, Rodman, and Hyams, 2003, p. 121) . The ex ample can be taken from

speech an d w riting s tyle, s uch as in the s entence which c lub di d y ou hi t t he

winning putt with? which is usually used in writing and speech while With which

club did you hit the winning put is a typical of formal writing (Miller, 2002, p.

12). Syntactical differences also refer to different grammatical rules. For instance,

Americans tend to use do you have instead of have you got that is commonly used

by British.

The next aspect is morphology which concerns with the internal structures

of words and how t hey are f ormed. In br ief, m orphology d eals w ith w ord

formation such as the use of affix that might give other meaning or even change

the w orld c lass ( Fromkin, R odman, a nd H yams, 2003, p. 69) . M orphological

differences clearly shape one word that comes from the same language, yet h as

different formation, such as the British dream is changed into dreamt by adding –

t suffix while American use –ed to form the word dreamed.

The last is semantic aspect which deals with the meaning of word, phrases,

and even sentences (Fromkin, Rodman, and Hyams, 2003, p. 173) . Specifically,

when talking about s emantic d ifferences, i t w ould r efer t o t he d ifferences o f

meaning of words, phrases, and sentences. The word homely for American people

means ugly, while for British people homely means down to earth.

2.1.5 Lexical Differences

As stated by Chambers and Trudgill (2003, p. 97), lexical differences refer

to d ifferent w ords used b y di fferent s peakers to point out the same o bject. T he

dictionaries ( Crystal, 20 08, p. 276) . T hey c onsist of s ome c ategories t hat a re

known as lexical categories. Lexical categories refer to the word-level syntactic

categories w hich c onsist of noun, ve rb, a djective, a nd a dverb t hat be long t o

content w ords w hile p ronouns, pr eposition, a rticle, a nd conjunction be long t o

function word (Fromkin, Rodman, and Hyams, 2009, p. 78). According to Miller

(2002, p. 35), content words which are also known as lexical words include nouns

(flower, milk, and eraser), verbs (go, drink, and sleep), adjective (beautiful, small,

and f ast), a nd adverbs (slowly, r apidly, and aut omatically). On t he ot her ha nd,

function w ords are known as g rammatical w ords and w hich include pr onouns,

such as it, she, they, preposition such as in, on, of, article such as the, that, these,

and conjunction, such as and, or, with ( Fromkin, Rodman, and Hyams, 2009, p.

78).

2.1.6 Standard Madurese

Madurese l anguage ha s 6 vow els, 31 c onsonants, 3 di phtongs, a nd 8

clusters. These six vowels are /a/, /i/, /u/, /ɛ/, /ǝ/, and /ɔ/. Madurese language has

Lexical differences in particular language are drawn by using isogloss. It is

a line which makes the boundaries between one area and the other area. Isogloss is

divided i nto 6 t ypes ( Chambers a nd T rudgill, 2004, p. 97) . T he f irst i s l exical

isogloss t hat di fferentiates t he a rea w hich us es different w ord i n poi nting s ame

object, such as the word dutch cheese in the northeastern region of North America

and cottage ch eese in t he A merican m idland. S econd, pr onunciation i sogloss

which s ometimes c onsidered in p art w ith le xical is oglosses th at d eals w ith

different pronunciation used in particular region, such as how Northern people of

North A merica p ronounce greasy by us ing [ s] c ompared w ith s outhern a nd

midland people who used [z]. In phonology, there are also two types of isogloss.

First i s phone tic i sogloss t hat r efers t o di fferent phone tic f orm of t wo r egions

caused by additional linguistic rule, such as /aj/ and /aw/ in Canadian English that

have hi gh ons et i n w ords l ike mice and mouse before voi celess obs truent t hat

usually applied in Canadian rule.

Opposed t o phonetic i sogloss, t here i s also phon emic i sogloss t hat deals

with phonemic di fferences, such as t he existence of phoneme / ʊ/ and /ʌ/ w here

northern people of England never acknowledge the word that have /ʊ/ and /ʌ/ to

be existed. The last type of isogloss is grammatical isogloss which is divided into

two types. The first is syntactic isogloss that deals with sentence formation, such

as t he u se o f for to in ma ny p arts o f th e E nglish-speaking w orld as a

complementiser, b y c ontrast, no s tandard di alect of E nglish, i n a ny p art of t he

world, includes for to among its complementiser (Chambers and Trudgill, 2004, p.

inflectional, and derivational differences in some regions, such the use of holp as

the p ast t ense o f help in S outh A merica, i n c ontrast t o helped elsewhere

(Chambers and Trudgill, 2004, p. 98).

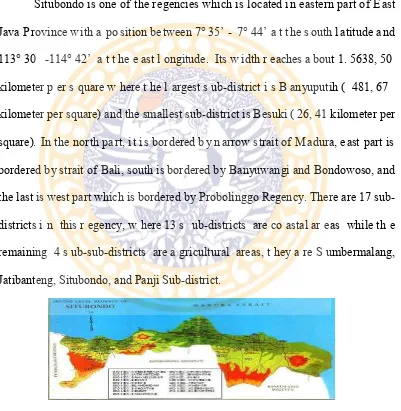

2.1.8 Monograph of Situbondo

Situbondo is one of the regencies which is located in eastern part of East

Java P rovince w ith a po sition be tween 7° 35’ - 7° 44’ a t t he s outh l atitude a nd

113° 30 -114° 42’ a t t he e ast l ongitude. Its w idth r eaches a bout 1. 5638, 50

kilometer p er s quare w here t he l argest s ub-district i s B anyuputih ( 481, 67

kilometer per square) and the smallest sub-district is Besuki ( 26, 41 kilometer per

square). In the north part, it is bordered by narrow strait of Madura, east part is

bordered by strait of Bali, south is bordered by Banyuwangi and Bondowoso, and

the last is west part which is bordered by Probolinggo Regency. There are 17

sub-districts i n this r egency, w here 13 s ub-sub-districts are co astal ar eas while th e

remaining 4 s ub-sub-districts are a gricultural areas, t hey a re S umbermalang,

Jatibanteng, Situbondo, and Panji Sub-district.

Figure 1 : The Map of Situbondo Regency

As one o f t he r egencies in Tapal K uda area, t here a re t wo d ominant

Kuda area is also known as Pandalungan area. According to Sutarto (2006, p. 1),

the term Pandalungan refers to the new culture as the result of blending process of

two or more cultures in particular area. However, the term Tapal Kuda refers to

the area that creates horse shoe form (Sutarto, 2006, p. 1).

Focusing onl y on M adurese l anguage, t here i s a l ong hi story behind

Situbondo pe ople w ho speak t his va riety. In 19th century, t here w as m ajor

migration o f M adurese people t o J ava Island, e specially i n e astern pa rt or E ast

Java Province that changed the society in this area which created what so called as

Pandalungan society (Syamsuddin, 2007, p. 162 ). Situbondo was becoming one

of r egencies t hat b ecome t he n ew l and f or Madurese pe ople. A s s tated b y

Syamsuddin ( 2007, p. 1 67), t he m igrators t hat c ame t o S itubondo w as c oming

from S umenep w hich gave t he pos sibility f or S umenep va riety t o b e s poken i n

this regency. Poverty became the main reason for Madurese people to come to this

regency. W orking a s farmer, t he s oil c ondition c ould not f ulfill t he de mand of

daily n eed. In t heir i sland, unf ertile s oil be came t he bi ggest pr oblem w hich

brought t hem t o t he di fficulty i n f ulfilling t he demand of s taple ( Kuntowijoyo

cited in Hartono, 2010, p. 4). It is different from Situbondo which provides fertile

soil that could give advantages for those who work in agricultural sector (Hartono,

2010, p. 5) . Another fact also strengthen the possibility that Situbondo variety is

influenced by Sumenep variety is because the first person who ruled Situbondo, at

that time its name was Besuki, was Pangeran Sumenep (Pemerintah Kabupaten

Another feature that could be found in Situbondo is the characteristics of

the area among villages. Situbondo is divided into two different area, coastal area

and a griculture ar ea. T he s ub-districts w hich are l ocated i n nor thern pa rt of

Situbondo are close to narrow strait of Madura, such as Besuki, Mangaran, and

Banyuputih sub-district. They have port that connects them to Madura Island. It

might become the reason for people in this area to work as fishermen. Kalbut port

is one of t he l argest por ts i n t his r egency w hich i s l ocated i n M angaran s

ub-district. M eanwhile, s ub-districts th at a re l ocated i n s outhern pa rt close t o

agriculture area. It i s s hown b y m ost of pe ople i n t hese a reas w ho work a s

farmers.

Even t hough t he va riety t hat i s us ed i n S itubondo a ssumed t o b e

influenced by Sumenep dialect, people in this regency often find lack of mutual

intelligibility in u nderstanding v arieties u sed in d ifferent s ub-disctricts. F or

example, pe ople i n w estern pa rt w ould s ay kowek [kɔwɜk] t hat re fers t o ‘o wl’

while people in eastern part would say beluk [bɜluk]. Another example is people

in northern part would say sengghik [sɛŋghIɁ] that refers to ‘crab’ while people in

southern would s ay kopeteng [kɔpɛtɛŋ]. It becomes the reason for researcher to

conduct the study about the lexical differences in Situbondo regency.

2.2 Related Studies

Awaliyah (2015) conducted study about the lexical differences in Kangean

Island, Sumenep regency. There were four OP(s) used in this study, which were

Dudo (OP1), Dandung (OP2), Torjek (OP3), and Pajanangger (OP4) which were

and cross-checking were c onducted b y us ing 450 w ords t hat c ould r epresent

variety used in this Island. The status of lexical differences was counted by using

dialectometry formula. The result showed that that there were out of 450 words,

there were 137 lexical differences. The index of lexical differences found between

Dandung and Torjek (48, 90 % ), D andung and Pajanangger (47, 44 %), Torjek

and Pajanangger (62, 04 %), Duko and Dandung ( 67, 15 %) and the last Duko

and P ajanangger ( 70, 8 0%) w hich br ought t o t he c onclusion t hat t he s tatus o f

lexical differences in Madurese varieties spoken by people in Kangean Island is

different Sub-Dialect and different dialect. The difference between her study and

my study is I analyzed lexical differences of Madurese varieties outside Madurese

Island. My study focused on Madurese variety in Situbondo regency.

The s tudy from A syatun ( 2005) e ntitled S tratigrafi Isolek Isolek B ahasa

Madura Dialek Pamekasan conducted in Pamekasan regency aimed to find isolect

stratigraphy of M adurese va riety s poken i n t his r egency. Using s ynchronic

approach, t he s tudy w as c onducting b y comparing 233 i sogloss i n s even

Observation Point (OPs) were sub-district that could represent lexical differences,

respectively Tlanakan, Pademawu, Pamekasan, Proppo, Larangan, Penganten, and

Pakong Sub-District. Three informants in each observation point were chosen to

gain the lexical differences by interviewing, note taking, and recording. 92 lexical

differences w ere f ound which c ould be c onsidered s peech di fferent. T his s tudy

also t ook pl ace i n M adura Island, w hile m y s tudy t ook pl ace out side Madura

The l ast s tudy w as c oming f rom T ri ( 2015) w ho s tudied P andhalungan

language spoken by Probolinggo people. This study was focusing on l exical and

phonological di fferences t hat e merged i n t his r egency as t he r esult of bl ending

process of two cultures, Madurese and Javanese. Descriptive and qualitative were

used t o i dentify t he di fferences b y us ing 200 glosses. T he r esult of t he s tudy

showed 40 l exical di fferences a nd 40 phonol ogical di fferences. This study i s

different f rom m y s tudy i s be cause I onl y f ocused o n l exical d ifferences i n

Madurese varieties while her study focused on lexical and phonological aspects of

CHAPTER III

METHOD OF THE STUDY

3.1 Study Approach

Qualitative descriptive approach was used in this study. Qualitative study

refers t o t he data collection t hat i nvolves non-numerical d ata w hich em phasizes

works in a wide range of data collection by doing interview study and working on

many t ypes of t ext ( Dornyei, 2007, p. 37 ). R elated t o t he s tudy, qu alitative

approach w as ap plied w hen an alysing an d i dentifying t he l exical d ifferences b y

conducting s ome activities w hich a re i nterviewing, r ecording, not e taking, a nd

cross c hecking ( Mahsun, 2005) . D ialectometry formula w as also us ed in t his

study to calculate the status of lexical differences in Situbondo variety.

3.2 Location

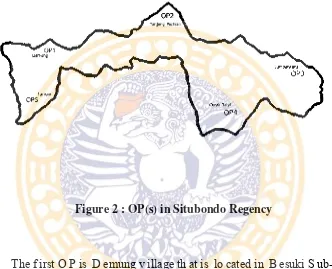

In this study, five OPs (Observation Point) were chosen. The term OP is

used to refer to the location taken as the area of the study (Mahsun, 2005, p. 130).

Five v illages in f ive s ub-districts h ad b een s elected as t he area f or t he s tudy,

respectively Demung (OP1), Tanjung Pecinan (OP2), Sumberwaru (OP3), Curah

Tatal (OP4), and Taman (OP5). They were chosen based on t he assumption that

they r epresent t he va riety i n w estern, nor thern, e astern, a nd s outhern pa rt of

Situbondo regency. However, there are some criteria in choosing the Observation

Points that represent varieties spoken in each Observation Point (OP) as proposed

1. The OP(s) should be far from central town.

2. The OP(s) should have low mobility.

3. The OP(s) should be occupied by more than 6.000 inhabitants.

4. The OP(s) should have existed for more than 30 years.

Figure 2 : OP(s) in Situbondo Regency

The f irst O P is D emung v illage th at is lo cated in B esuki S ub-District,

western pa rt of S itubondo. Its w idth r eaches 3.59 km s quare ( Statistik D aerah

Kecamatan B esuki, 201 4). It i s a lso one of t he vi llages t hat are near t he s ea

(Statistik Daerah Kecamatan Besuki, 2014).

The s econd O P i s T anjung P ecinan vi llage, l ocated i n M angaran s ub-

district, northern part of Situbondo regency which is well known as coastal area

and becomes the reason why this area is very identical with fisherman. Fisherman

becomes the second biggest occupation after farmer (Statistik Daerah Kecamatan

Mangaran S ub-District. I ts w idth reaches 11.71 km s quare. T he di stance from

Tanjung Pecinan to Central Town is about 8.5 k m (Statistik Daerah Kecamatan

Mangaran, 2014).

The t hird O bservation P oint i s S umberwaru vi llage w hich i s l ocated i n

Banyuptih Sub-District, the eastern part of Situbondo Regency. Its width is about

111.27 km square. It t akes an hour t o go t o t he central t own since t he distance

reaches 36 km . T his vi llage i s inhabited by 8.3 86 i nhabitants, c onsist of 4.195

males ad 4.191 females. Sumberwaru has the lowest population density ratio. It is

only about 35 inhabitants per km square (Statistik Daerah Kecamatan Banyuputih,

2014).

The f ourth obs ervation point i s Curah T atal w hich i s l ocated i n A rjasa

Sub-district, southern part of Situbondo. This village is the second largest village

in Arjasa district after Jati Sari village. Its width is about 42,56 km square and is

occupied b y m ore t han 7.000 i nhabitants. S ince i t i s not a c oastal a rea, t he

majority o f in habitants a re w orking a s farmers ( Statistik D aerah K ecamatan

Arjasa, 2014).

The l ast obs ervation poi nt i s T aman vi llage w hich i s l ocated i n

Sumbermalang s ub-district, t he s outhern pa rt of S itubondo Regency. The

percentage of its width is about 9.94% and it makes Taman as one of the smallest

villages in this district (Statistik Daerah Kecamatan Sumbermalang, 2014).

There a re s ome r easons t hat s upport the researcher t o ch oose t hose f ive

villages as the OP(s). The first reason is that those villages are rural areas which

usually conducted i n r ural a rea b ecause i ts v ariety has authentic ch aracteristic

which is still pure. Second reason is because those villages have low mobility. It is

because t he d istance o f those v illages t o t he ci ty is quite far which m akes t he

inhabitants rarely go the city. It makes them rarely make contact with people in

central town. The last reason is because the phenomenon of lexical differences in

those villages is prevalent.

3.3 Population and Sample

Talking a bout a n a rea, i t cannot be s eparated f rom t he pe ople w ho l ive

there. In t his s tudy, those pe ople are called as p opulation. T he t erm pop ulation

means a group of people where the study takes place while a particular group of

population whom the researcher wants to examine in a particular context is called

as sample (Dornyei, 2007, p. 96). A sample is more specific than population since

it deals with some criteria, such as age, gender, education, social class status, and

etc. F or t his s tudy, t he population w as M adurese s peaker i n S itubondo r egency

while t he s amples w ere Madurese s peakers w ho l ive i n f ive o bservation p oints

and who w ere c hosen a s t he i nformants. C onducting t his s tudy, t he r esearcher

chose three informants in each OP which means there were fifteen informants that

were chosen in this study. Purposive sampling was also used in this study. It is the

technique to choose the samples that would give the most representative result of

the study (Babbie, 2007). The informants chosen as the samples of this study had

met the following requirements (Ayatrohadi, 2003, p. 39):

1. Rural men or women.

3. Physically and mentally healthy.

4. Born i n observation poi nt and has f amily or relatives who i nhabit i n

the same observation point.

5. The mobility of informant should be low.

6. Informants have pride in their variety.

7. The informant could speak Indonesia language.

8. Graduated at least from primary school.

Similar t o A yatroehadi, Chambers a nd T rudgill ( 2004, p. 29) a lso g ive

some c riteria f or t he i nformant, know n a s N ORM w hich s tands f or N(Non

mobile), O(Older), R(Rural) and M(Males). In addition, Chambers and Trudgill

emphasize more on rural males since males tend to speak in informal form that is

much needed in conducting dialectology study.

3.4 Instrument of the study

The instrument of this study refers to the word list that was used and asked

to the informants since this study was dealing with lexical differences. The word

list included 200 Swadesh words with 250 additional words from lauder (cited in

Mahsun, 2005, p. 140). This word list consists of adjective, verb, colour, number,

conjunction, and etc. Swadesh words were chosen by considering that those words

do not e asily change ove rtime. Moreover, t he w ord l ist t hat w as t aken f rom

Lauder which is about environment, food, drink, part of village and life, part of

house, na ture, a nd etc. represents the ch aracteristics o f the ar eas in th is study.

According t o Ayatrohadi (2003, p. 39) t he word l ist t hat was used i n t he study

1. The words should be able to show special characteristic of variety used

in the area of the study.

2. The words represent the culture of the area of the study.

3. The words should be answered directly and spontaneously.

3.5 Techniques of Data Collection

After setting the instrument and choosing the Observation Points (OPs) for

this study, the da ta c ollection w as done . S ince this s tudy concerned with t he

spoken va rieties in p articular ar eas, o ral m ethod ( interview) w as used as t he

technique o f d ata co llection. Beside i nterview, t he r eseracher al so car ried o ut

other activities such as recording, note taking, and cross-checking.

During t he i nterview, t he researcher al so did complete participation. A s

stated b y D uranti ( 1997, p. 100) , complete p articipation is ve ry us eful during

study. It is because the researcher directly interacts by using the local language,

especially w hen t he r esearcher also co mes f rom t he s ame r egion with t he

informants. H owever, d uring the interview, Bahasa I ndonesia was used by t he

researcher for the words being questioned to the informants so that the reseracher

would not i nfluence t he s poken va riety of t he i nformants. T he que stions w ere

asked to the informants to get the most natural answers (Trudgill, 2004, p. 22) .

The researcher sometimes used a question such as ‘’ What is this?’’ by pointing to

an obj ect r eferred t o. It would l ead t he i nformants t o na me the obj ect b y us ing

their own variety.

Another a ctivity was r ecording. Recording was a lso c onducted while

recording da ta w ould be ve ry us eful f or the transcription p rocess t o m ake s ure

how t he w ords were pr onounced b y t he i nformants. Beside t he r ecording, t he

reseracher also did note taking. The note taking was done by transcribing directly

the words spoken b y the informants during interview process. It means t hat the

transcription was written while listening to the informants. Actually this activity

needed b etter comprehension a bout phonol ogy and IPA s ymbol t hat w ould be

used during interview.

Finally, the researcher crosschecked the data which were not clear. If the

reseracher doubted the words given by the informants, the reseacher crosschecked

the use of the words in a natural setting.

3.6 Techniques of data analysis

In t his s tudy, t here were three s teps o f d ata an alysis. T he f irst s tep w as

comparing and contrasting the lexical items (Mahsun, 2005, p. 144). In this step,

each l exical i tem w as tabulated based o n t he variety t hat was u sed i n ea ch

observation point. Each observation point might have different lexical forms.

Table 1: Lexical Item Identification in each OP

NO Gloss Code Lexical Form

OP 1 OP2 OP 3 OP 4 OP 5

1 Gloss ‘owl’ bhɜlʊk bhɜlʊk bhɜlʊk bhɜlʊk kɔwɜk

2 finger’ Gloss ‘ Middle panɔŋgʊl tɔndʒtǝŋah hʊɁ tǝŋah tɔndʒhʊɁ tɔndʒtǝŋah hʊɁ tɔndʒtǝŋah hʊɁ

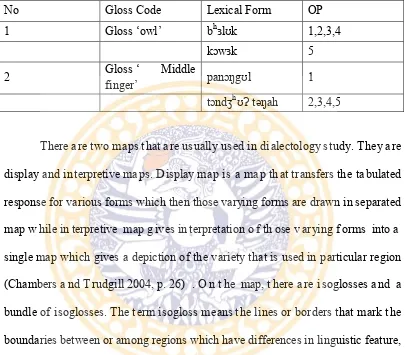

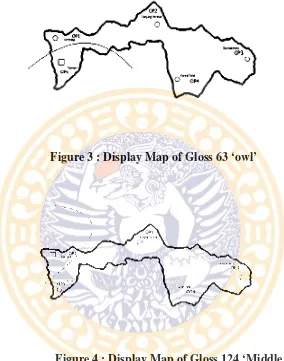

The next step was analysing the lexical differences that would be drawn in

that was used in each observation point, whether or not some Observation Points

used the same lexical word.

Table 2: Lexical Item Distribution in OP

No Gloss Code Lexical Form OP

1 Gloss ‘owl’ bhɜlʊk 1,2,3,4

kɔwɜk 5

2 Gloss ‘finger’ Middle panɔŋgʊl 1

tɔndʒhʊɁ tǝŋah 2,3,4,5

There are two maps that are usually used in dialectology study. They are

display and interpretive maps. Display map is a map that transfers the tabulated

response for various forms which then those varying forms are drawn in separated

map w hile in terpretive map g ives in terpretation o f th ose v arying f orms into a

single map which gives a depiction of the variety that is used in particular region

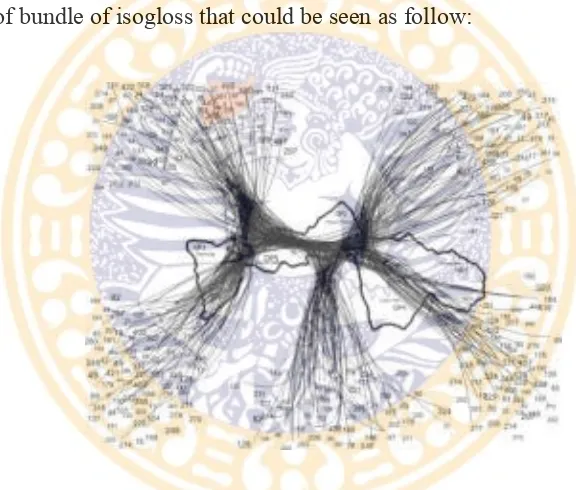

(Chambers a nd T rudgill 2004, p. 26) . O n t he map, t here a re i soglosses a nd a

bundle of isoglosses. The term isogloss means the lines or borders that mark the

boundaries between or among regions which have differences in linguistic feature,

while a bundle of isogloss stands for the accumulation of the lines or borders in

distributing the differences of linguistic features (Chambers and Trudgill, 2004, p.

89). A ccording t o M ahsun ( 2005, p. 145 ), t here a re t hree s teps o f d rawing

isogloss. They are

a. Drawing line (isogloss) on the map,

b. Starting to draw the line (isogloss) from the largest distribution of the

c. One difference is counted as one isogloss.

The appearance of display map and bundle of isogloss map is shown below:

Figure 3 : Display Map of Gloss 63 ‘owl’

Figure 4 : Display Map of Gloss 124 ‘Middle Finger’

The la st s tep w as d etermining th e s tatus of t he l exical d ifferences and

interpreting th e r esult. In th is s tudy, d ialectometry w as u sed a s th e f ormula to

determine the status of the lexical differences. The status of the lexical differences

would be known after determining the percentage of the differences. As proposed

by Mahsun (2005, p. 154), the dialectometry formula is written as follow:

s x 100%

Index d% =

n

d : the vocabulary distance in percentage

s : the number of lexical differences in one OP compared to

other OP

n : the total number of the lexical differences.

After calculating t he d ata, t he s tatus o f the l exical d ifferences will b e

gained. Mahsun (2005, p. 155) classifies the status of variety into five types They

are :

Index Percentage Category

Under 20% No difference

21-30% Different speech

31-50% Different Sub-dialect

51-80% Different dialect

In brief, the steps in analysing the data are described as follow:

1. Comparing and contrasting the l exical items used in the Observation

Points by tabulating the data into the first table. (See table 1)

2. Analysing t he l exical d ifferences b y tabulating the w ord lis t in to th e

second table. (See table 2)

3. Drawing two different maps, display and interpretive map to define the

lexical differences.

4. Determining the lexical differences by using dialectometry formula.

CHAPTER IV

FINDING AND DISCUSSION

This c hapter consists of t wo s ections w hich are f inding and di scussion.

The finding describes the lexical differences and the status of lexical differences

spoken by people in Situbondo regency, while the discussion section interprets the

finding.

4.1 Finding

4.1.1 The lexical differences

Based o n t he d ata collection an d d ata analysis, t here a re m any l exical

differences that are found among OP(s). Those lexical differences are spoken by

the people in their daily activity. 133 glosses out of 450 show lexical differences.

In the description below, the number in the bracket is the number of the gloss. The

description also explains the origin of the word.

1. Thick (4)

There are two variations used for gloss ‘thick’. They are kandhel [kandhel] and tebel [tǝbǝl]. The first form, [kandhel] is used in OP2, OP4, and OP5

while th e te rm tebel [tǝbǝl] is used in OP1, OP3, and OP4. The term

kandhel [kandhel] m eans ‘thick’ (Safioedin, 1976 , p. 268) which has t he

same meaning with tebel [tǝbǝl] (Safioedin, 1976, p. 615).

2. Narrow (8)

of house (Safioedin, 1976, p. 152), while the second variety, keni’ [kɛniɂ]

in M adurese m eans ‘ small’ ( Safioedin, 1976, p. 292) . T he t erm cope’

[tʃᴐpɛɂ] is used in OP1, OP3, OP4, ad OP5 while the term keni’ [kɛniɂ] is

used in OP2, OP4, and OP5. Even though both of them do not have same

meaning, but they are still related to each other.

3. Warm (10)

There are two variations for gloss ‘warm’. The first variety angak [aŋaɂ] is

used in OP1, OP2, OP3, and OP5. Meanwhile the term panas [panas] is

only used in OP4. T he term angak [aŋaɂ] means ‘warm’ or not too hot

(Safioedin, 1976, p. 67). On the other hand, the term panas [panas] means

‘hot’(Safioedin, 1976, p. 439) . Both of those term are still related to each

other.

4. Full (12)

There are two varieties refers to the gloss ‘full’. The first variety is possak

[pᴐssaɂ] which is used in OP1, O P3, O P4, a nd O P5, w hile t he s econd

variety bennyak [bǝñaɂ] is only used in OP2. These two varieties have no

same m eaning, b ut s till r elated t o each o ther. The f irst v ariety possak

[pᴐssaɂ] refers more to availability of things/goods (Safioedin, 1976, p.

483), w hile t he va riety bannya’ [bǝñaɂ] refers to the quantity of

thing/goods (Safioedin, 1976, p. 97)

5. New (13)

There are two varieties used for the gloss ‘new’. The first variety is anyar

buru [bhʊrʊ] is used on OP2. Anyar [añar] here means ‘something n ew’

which does not the same meaning with buru [bhʊrʊ] (Safioedin, 1976, p. 74) but still related to each other. The variety variety buru [bhʊrʊ] means

something t hat j ust happens recently (Safioedin, 1976, p. 128) . B oth o f

these varieties are derived from old Madurese.

6. Rotten (17)

The gloss ‘rotten’ also has two varieties that still related to each other. The

first variety bucco’ [butʃᴐɂ] is used in OP1, OP3, OP4, and OP5 while the

second variety beu [bǝʊ] is used in OP2 and OP4. According to Safioedin

(1976, p. 120 ), bucco’ [butʃᴐɂ] refers more to fruits and it relates to beu

[bǝʊ] which means something that does not smell good (Safioedin, 1976,

p. 104) have the same meaning, ‘dirty’.

8. Smooth (21)

There are also two varieties of ‘smooth’. The first variety lembu’ [lǝmbʊɂ]

refers more to the texture of something (Safioedin, 1976, p. 341), while the

second va riety alos [alɔs] refers more to t he s urface of s omething

[lǝmbʊɂ] is used in OP1, OP3, and OP4 while alos [alɔs] is used in OP2

‘have no’ and endi’ means ‘something’ which b ecome ‘having nothing’.

Only mesken [mɛskɛn] and malarat [malarat] ar e d erived f rom o ld

Madurese.

10.Diligent (32)

There are three varieties used for gloss ‘diligent’. The first variety, bajeng

[bhǝdʒǝŋ] is used in OP1, OP2, OP4, and OP5. This variety related to ‘someone w ho a lways s tudy ha rd’ ( Safioedin, 1 976, p. 88) . T he s econd

variety banter [bhǝntǝr] is used only in OP3. This variety means ‘someone who is really responsible to do some works’ (Safioedin, 1976, p. 98) . The

last v ariety, penter [pɛntǝr] is used only in OP4. Even though penter

[pɛntǝr] is not having same meaning with bajeng [bhǝdʒǝŋ], but they still share common thing because penter [pɛntǝr] here means ‘someone who is

good in academic’ (Safioedin, 1976, p. 466) . Although the three varieties

11.Healthy (34)

There are t wo v arieties for ‘healthy’. B asically, these t wo v arieties h ave

the same meaning. The first variety sehat [sɛhat] means ‘having no

problem w ith t heir he alth’ ( Safioedin, 1976, p. 546) . M eanwhile t he

second variety beres [bǝrǝs] has two meaning. The first meaning is

‘someone who has recovered from their sick’ while the second meaning is

‘someone w ho ha s no mental pr oblem’ ( Safioedin, 1976, p. 99) . T he

variety sehat [sɛhat] is used in OP1, OP3, and OP4 while beres [bǝrǝs]

here is used in OP1, OP2, OP4, and OP5.

12.Difficult (35)

There are two varieties used for ‘difficult’. The first variety sossa [sɔssa] is

used in OP1. Sossa [sɔssa] here means ‘having dificulty’ (Safioedin, 1976,

p. 586) . M eanwhile, t he s econd va riety sara [sara] h ere m eans ‘ critical

condition of he alth pr oblem’ ( Safioedin, 1976, p . 537) w hich i s us ually

used OP2, OP3, OP4, and OP5. Although they have different meaning, but

they are still related to each other, ‘having problem or difficulty’.

13.Greedy (37)

There are also two varieties for ‘greedy’. The first variety tama’ [tamaɂ] is

used i n O P1, O P2, O P3, a nd O P4 w hile the second va riety belekka

[bǝlǝkka] is used in OP1 and OP5. Tama’ [tamaɂ] here means ‘greedy’

(Safioedin, 1976, p. 598 ), while there is no t erm belekka [bǝlǝkka] in old

Madurese. It gives the assumption that belekka [bǝlǝkka] is a new form of

14.Wise (40)

All OP(s) except OP3 have no term that refers to gloss ‘wise’. In OP3, the

term adil [adhil] refers to ‘wise’. According to (Safioedin, 1976, p. 54] adil

[adhil] here means ‘being fair’. Though, it does not give the real meaning

of ‘wise’, the variety adil [adhil] still has related meaning. 15.Wasteful (44)

There ar e t hree v arieties u sed f or ‘ wasteful’. The f irst v ariety tarapas

[tǝrapas] that is used in OP1 has meaning ‘like spending money’

(Safioedin, 1976, p. 610). The second variety boros [bɔrɔs] is used in OP2,

OP3, and OP4 which could not be found in old Madurese, yet it could be

found i n J avanase l anguage w hich ha s t he s ame m eaning with B ahasa

Indonesia ‘boros’ (Mangunsuwito, 2002, p. 311 ). The last variety matade’

[matadǝɂ] is used only in OP5. There is no term matade’ [matadǝɂ] which

gives the possibility that it is a new form of Madurese variety.

16.Swollen (45)

There a re t wo v arieties used f or ‘ swollen’. T he first v ariety bara [bǝrǝ]

deals with the swollen in part of body (Safioedin, 1976, p. 98) , while the

second v ariety bengka [bǝŋka] means something which is getting bigger

(Safioedin, 1976, p. 109) . Those varieties do not have exact meaning, but

they s hare c ommon t hing, ‘ getting bi gger’. Bara [bǝrǝ] is used in OP1,

OP2, OP3, and OP4, while bengka [bǝŋka] is used in OP4 and OP5.

There are t wo va rieties us ed f or ‘arrogant.’ t he f irst va riety s ombong

[sɔmbɔŋ] is used in OP1, OP2, OP3, and OP4. While the second variety

angko [aŋkɔ] is used in OP1 and OP5. Both of those varieties are derived

from o ld M adurese t hat r efer t o t he s ame m eaning, a rrogant ( Safioedin,

1976).

18.Fast (47)

There are t hree v arieties u sed f or ‘ fast.’ t he f irst v ariety ceppet [tʃǝpǝt]

which means ‘fast’, used in OP1 and OP4 (Safioedin, 1976, p. 146) . The

second variety santa’ [santaɂ] that also means ‘fast’ but refers more to the

flow of water (Safioedin, 1976, p. 534) which is used in OP2, OP3, and

OP4. T he l ast va riety, gancang [ghǝntʃaŋ] or kancang [kantʃaŋ] which

mean ‘fast’ but refers more to how people walk is used in OP2 and OP5

(Safioedin, 1976, p. 203).

19.Slow (48)

There are two varieties used for gloss ‘slow’. The first variety, laon [laɔn]

is us ed n O P1, O P3, O P4, a nd O P5. M eanwhile t he s econd va riety lere

[lɛrɛ] is used in OP2, OP4, and OP5. Those varieties have the same

meaning, ‘slow’ which are derived from old Madurese (Safioedin, 1976)

20.Lazy (49)

There are several varieties for ‘lazy’. The first variety lesso [lǝssɔ] is used

in OP1. Lesso [lǝssɔ] here means ‘very tired’ which is still relate to ‘lazy’

(Safioedin, 1976: 347). The second variety, nakal [nakal] is used in OP2.

especially for kids. The third variety males [malǝs] is used in OP3. Males

[malǝs] here means lazy (Safioedin, 1976, p. 362). The next variety,

polempoan [pɔlɛmpɔan] is used in OP4 which has meaning ‘feeling weak’

(Safioedin, 1976, p. 342) . The last variety, sengka [sǝŋka] is used in OP5.

Sengka [sǝŋka] here means ‘having no willingness to do something’ which

also refers to ‘lazy’ (Safioedin, 1976, p. 556) . Even though those varieties

have no same meaning, but they are still related to each other.

21.Angry (51)

There are three varieties for ‘angry’. The first variety gigir [ghighir] is used

in O P1 a nd O P5. Gigir [ghighir’] he re m eans ‘ shouting t o s omeone’ (Safioedin, 1976, p. 217 ). T he s econd va riety, ngoso’ [ŋɔsᴐɂ] is used in

OP2. T here i s no e xplanation a bout ngoso’ [ŋɔsᴐɂ in old maduree that

brings to the assumption this is a new variety of Madurese. The last variety

is getak [ghǝtak] which is used in OP3 and OP4. There is no term getak

[ghǝtak] in old Madurese. 22.Swan (59)

There ar e t wo v arieties for t he gloss ‘ swan’. T he f irst v ariety i s banyak

[bhǝñak] which is used in OP1, OP2, OP3, and OP4. Banyak [bhǝñak] here

means ‘swan’ in Javanese (Mangunsuwito, 2002, p. 305) while there is no

term bengoi [bhǝŋɔI] in Madurese. 23.Pig (60)

There are two varieties for gloss ‘pig’. The first variety babi [bǝbi] is used

1976, p. 84) . The second variety celeng [tʃɛlɛŋ] is used in OP1 and OP5.

Celeng [tʃɛlɛŋ] means ‘wild boar’ which is still similar feature to the first

variety (Safioedin, 1976, p. 143).

24.Owl (63)

There are two varieties of gloss ‘owl’. The first variety, belluk [bhǝlʊk] is

used in OP1, OP2, OP3, and OP4. The second variety kowek [kɔwǝk] is

used onl y i n O P5. Kowek [kɔwǝk] is assumed to be a new form of

Madurese variety. Both of those varieties refer to the same gloss, ‘owl’.

25.Crab (67)

There is one variety used in OP1, OP2, OP3, and OP5 for gloss ‘octopus’

(Safioedin, 1976, p. 207) while OP4 has no term for ‘octopus’.

27.Turtle (78)

There is only one variety for gloss ‘turtle’. The term is penyo [pǝñɔ] which

is used in OP1, OP2, OP3, and OP4. OP5 has no term for ‘turtle’.

28.Big Black Ant (82)

There are two varieties for gloss ‘big black ant’. The first variety lenying

‘pinching h ardly’ ( Safioedin, 1976, p. 344) w hile t here i s no t erm

kongrokong [kɔŋrɔkɔŋ] in old Madurese. It brings to the assumption that

this is a new form of Madurese variety.

29.Jelly fish (83)

There is only one variety for gloss ‘jelly fish’ which is used in OP1, OP2,

OP3, a nd O P5. T he t erm bubur [bʊbʊr] used in those OP(s) has no

explanation in old Madurese.

30.Fat (n) (90)

There are t wo v arieties for gloss ‘f at’. T he fi rst v ariety gaji [ghǝdʒi] is

used in OP1, OP2, OP3, and OP5 while the second variety pellem [pǝllǝm]

is us ed i n O P4. Both gaji gaji [ghǝdʒi] and pellem [pǝllǝm] are derived

from old Madurese which means ‘fat (n)’ (Safioedin, 1976).

31.Back (n) (110)

There are two varieties for gloss ‘back’. The first variety tengnga [tǝŋa] is

used i n O P1 w hile t he second va riety buggik [bʊgghik] i s us ed i n O P2, OP3, OP4, and OP5. There are no e xplanation for those two varieties in

there is no term benggibeng [bhǝŋghibhǝŋ] in old Madurese. It might be the

new form of Madurese variety.

33.Middle finger (124)

There a re t wo v arieties fo r g loss ‘m iddle fi nger’. T he first v ariety

panonggul [panɔŋgʊl] is used only in OP1 which is assumed to be the new

variety while the second variety tonju’ tengnga [tɔndʒhʊɂ tǝŋah] is used in

OP2, OP3, OP4, and OP5. Tonju’ tengnga [tɔndʒhʊɂ tǝŋah] maintains the old form of Madurese which refers to part of finger (Safioedin, 1976, p.

651).

34.Little finger (128)

There a re tw o v arieties f or g loss ‘ little f inger’. T he f irst v ariety entek

[ǝntɛk] or [tɛk ǝntɛkan] is used in OP1, OP3, and OP5 while the second

variety tonjju’ bilis [tɔndʒhʊɂ bilis] is used in OP2, OP4, and OP5. Enthek

[ǝntɛk] or tek enthekan [tɛk ǝntɛkan] is derived from old Madurese. It is a

term used to refer to ‘little finger’ (Safioedin, 1976, p. 188) . There is no

term tonju’ b ilis [tɔndʒhʊɂ bilis] in old Madurese. The term tonju

[tɔndʒhʊɂ]] means ‘finger’ while bilis [bilis] means ‘ant’. People in those op(s) use the term tonju’ bilis [tɔndʒhʊɂ bilis] might because little finger is

smallest finger among the others.

35.Buttom (n) (134)

There are some varieties for gloss ‘bottom (n)’. The first variety monteng

[mɔntǝŋ] is used in OP1 and OP3. The second variety tongkeng [tɔŋkɛŋ] is

while t he v ariety buri’ [bʊrik] is used in OP5. Tongkeng [tɔŋkɛŋ] is

derived from ol d M adurese which ha s m eaning ‘ hip’ not ‘ buttom’

(Safioedin, 1976, p. 649), but both of them are part of lower body which is

still related to each other. Bingkeng [biŋkɛŋ] based on Safioedin (1976, p.

116) refers to ‘waist’ which also part of lower body. The last variety, buri’

[bʊrik] here means ‘bottom’. It maintains the old form of Madurese

(Safioedin, 1976, p. 128). However, there is no term monteng [mɔntǝŋ] in

old Madurese.

36.Waist (135)

There are three varieties for gloss ‘waist’. The first variety teng entengan

[tɛŋ ǝntɛŋan] is used in OP1 and OP5. The second variety tengnga [tǝŋa] is

used in OP3 while the last variety pongkelpongan [pɔŋkǝlpɔŋan] is used in

OP4. O P2 ha s no term f or gloss ‘ waits’. T here is no e xplanation f or a ll

those varieties which bring to the assumption that they are the new form in

Madurese varieties spoken by people in Situbondo.

37.Hip (137)

There a re t wo v arieties for gloss ‘ hip’. M adurese va riety for gloss ‘ hip’

and ‘waist’ are used interchangeably. The first variety bingkeng [biŋkɛŋ]

is us ed i n OP1 and OP2 while the variety monteng [mɔntǝŋ] is used in

OP2, OP3, OP4, and OP5. Bingkeng [biŋkɛŋ] based on Safioedin (1976, p.

116) refers to ‘waist’ which also part of lower body while there is no term

monteng [mɔntǝŋ] in old Madurese which brings to the a ssumption t hat

38.Lung (139)

There are t wo v arieties for gloss ‘ lung’. T he first v ariety paro [parɔ] is

used in OP1, OP3, OP4, and OP5 while the second variety bara [bhǝrǝ] is

used in OP1 and OP2. Bara [bhǝrǝ] is derived from old Madurese which

refers to part of body ‘lung’ (Safioedin, 1976, p. 98) while there is no term

paro [parɔ] in old Madurese.

[nǝŋǝnnǝŋ] is used in OP1, OP2, OP3, and OP4 while the second variety

odi’ [ɔdiɂ] is used in OP5. Odi’ [ɔdiɂ] means ‘stay’ which is similar to

‘live’ ( Safioedin, 1976, p. 397) w hile t here i s no t erm neng nge nneng

[nǝŋǝnnǝŋ] in old Madurese.

41.Talk (154)

There are three varieties for gloss ‘talk’. The first variety acaca [atʃatʃa] is

used i n O P1, O P2, O P3, a nd O P5. Acaca [atʃatʃa] here means ‘talk’