Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 11 January 2016, At: 22:16

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

An Extension of the Theory of Reasoned Action in

Ethical Decision Contexts: The Role of Normative

Influence and Ethical Judgment

Kevin Celuch & Andy Dill

To cite this article: Kevin Celuch & Andy Dill (2011) An Extension of the Theory of Reasoned Action in Ethical Decision Contexts: The Role of Normative Influence and Ethical Judgment, Journal of Education for Business, 86:4, 201-207, DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2010.502913 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832323.2010.502913

Published online: 21 Apr 2011.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 319

View related articles

ISSN: 0883-2323

DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2010.502913

An Extension of the Theory of Reasoned Action in

Ethical Decision Contexts: The Role of Normative

Influence and Ethical Judgment

Kevin Celuch and Andy Dill

University of Southern Indiana, Evansville, Indiana, USA

The moral conduct of organizations is ultimately dependent on the discrete actions of in-dividuals. The authors address the scholarly and managerial imperative of how individuals combine various cognitions in their ethical decision making. The study extends the under-standing of ethical decision making by exploring relationships among Theory of Reasoned Action–relevant constructs. Specifically, the authors examined a model that included an ex-pansion of normative influence to include a behavioral norm and an ethical judgment construct as proximal to intention. To their knowledge, these relationships had not been simultane-ously explored in the business ethics literature. Responses from a multidisciplinary student sample to 2 ethical scenarios were examined with structural equation modeling and largely support-hypothesized relationships. Results hold implications for future theory, research, and management of individual-level ethical decision making.

Keywords: ethical decisions, ethical judgment, theory of reasoned action

Over the past four decades, ethical behavior in business has been the focus of researchers across multiple disci-plines. While various players have been implicated in eth-ical transgressions over this time, the real story relates to the damage to individuals, organizations, industries, and per-haps economies, particularly in light of the recent subprime mortgage fiasco. In response to unethical conduct, regula-tory and policy initiatives at the level of organizations and industries have been promulgated and implemented and more are sure to follow, yet, as recognized by Lagace, Dahlstrom, and Gassenheimer (1991), the moral conduct of organiza-tions is ultimately dependent on the discrete acorganiza-tions of indi-viduals. Indeed, Haytko (2004), in exploring organizational relationships, observed that it is difficult for employees to think in terms of relationships between firms without think-ing of relationships between individuals. In order to effec-tively prepare individuals to assume roles as responsible business professionals, it is important for business educa-tors and corporate trainers to understand the nature of ethical decisions so that enhanced curriculum and training can be

Correspondence should be addressed to Kevin Celuch, University of Southern Indiana, College of Business, 8600 University Boulevard, Evansville, IN 47712, USA. E-mail: [email protected]

developed to improve ethical decision making. Thus, under-standing individual-level ethical conduct in business contexts is a continuing imperative.

Two important themes embedded in literature aimed at understanding individual-level ethical decision making and behavior relate to (a) the need for theory-driven, program-matic research (cf. Gibson & Frakes, 1997; Hunt & Vitell, 1986); and (b) the need for developing an understanding that moves beyond mere knowledge of rules or facts to a more nuanced perspective of how individuals weigh and combine various elements of experience related to ethical reasoning (cf. Anderson, 1997; Dubinsky & Loken, 1989).

One approach that has received attention in the business ethics literature is grounded in social psychological per-spectives that explain intention and behavior (Ajzen, 1985, 1991; Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975). A clear strength of this ap-proach is that it combines well-grounded theory that explains how individual-level cognitions combine to determine inten-tion and behavior with the potential for practical, problem-relevant interventions based on the theory. Insights gained from the use of these models attests to their potential for in-creasing our understanding of ethical intention and behavior in business contexts (Buchan, 2005; Carpenter & Reimers, 2005; Cherry, 2006; Dubinsky & Loken, 1989; Gibson & Frakes, 1997).

202 K. CELUCH AND A. DILL

The present study extends this line of research in three ways. We echo the admonition related to the need for theory-based, programmatic research. To this end, we explored a variant of the Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA) that pro-poses two theoretical extensions to applications of the model in the ethical domain. Literature in the area raises theoretical issues with respect to variables that might further researchers’ understanding of the determinants of behavioral intentions and ultimately behavior. One issue relates to the expansion of normative influence to include a behavioral norm in ad-dition to a subjective norm; a second issue relates to the addition of an ethical judgment construct to the TRA model. In the next section of the article, we briefly review the theoretical model that is the foundation of this research. We describe the specific model to be tested along with justifi-cation for proposed constructs and relationships. Then, we provide an overview of the methodology of the study and then present the findings. In final section we discuss results and address theoretical, research, and managerial implications.

Theory of Reasoned Action

The TRA (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980; Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975) places intention as the immediate antecedent of behavior, and thus the stronger the intention the more likely the occur-rence of the corresponding behavior. Determining intention are attitude and subjective norm. The attitude component is composed of beliefs, the perceived likelihood of particular consequences of the behavior, weighted by an evaluation of the consequences. The subjective norm component is con-ceptualized as normative beliefs, the perceived pressure from salient referents, weighted by the motivation to comply with the referents. The TRA has received support across a range of contexts (cf. Eagly & Chaiken, 1993; Sheppard, Hartwick, & Warshaw, 1988). The TRA was developed to deal with behaviors that are under an individual’s volitional control (Ajzen, 1988; Fishbein, 1993).

Ajzen (1988, 1991) proposed an extension to the TRA—a perceived behavioral control construct. Perceived behavioral control relates to the ease or difficulty of performing a behav-ior in which an individual’s volitional control may be called into question. Additionally, calls have been renewed for the exploration of additional constructs that might expand these models (Conner & Armitage, 1998).

A Conceptual Extension of the Theory of Planned Behavior for Ethical Decision Making

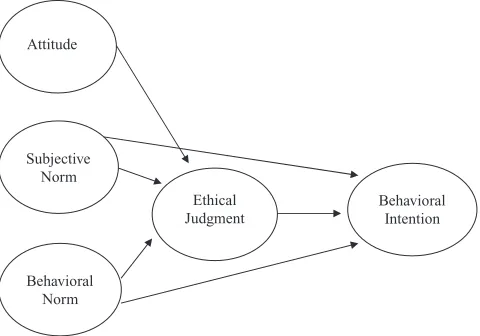

Figure 1 depicts a model adapted from the TRA that inte-grates constructs from related attitudinal and ethical decision making literature. In the model, intention to engage in an ethically questionable action is determined by the attitude toward the act, the subjective norm toward the act, the be-havioral norm toward the act, and an ethical judgment with respect to the act. The attitude, subjective norm, and behav-ioral norm components are viewed as immediate antecedents

Attitude

Subjective Norm

Behavioral Norm

Ethical Judgment

Behavioral Intention

FIGURE 1 A conceptual extension of the theory of reasoned action for ethical decision making.

of the ethical judgment. The ethical judgment and the subjec-tive and behavioral norms are also posited to directly affect behavioral intention. Justification for specific hypotheses de-veloped from relevant literature follows.

Attitude, subjective norm, and intention related to the act are the foundation of the TRA. These constructs have been featured prominently in prior research in the ethical decision-making domain and are thus included in the present research as relevant antecedents (attitude and subjective norm) and outcome (intention) variables (cf. Buchan, 2005; Carpenter & Reimers, 2005; Cherry, 2006; Dubinsky & Loken, 1989; Gibson & Frakes, 1997).

Although most of the research utilizing intention models has included a subjective norm (i.e., an individual’s view about what significant others think the individual should do in a given context), discussion has been raised regarding the concept of a behavioral norm (i.e., an individual’s belief about what others are doing in a given context) as an indepen-dent predictor in attitude models (Kashima & Gallois, 1993). Care in selecting the appropriate normative constructs is in keeping with Eagly and Chaiken’s (1993) caution against insufficient consideration of the social context of attitudes and intentions as well as with reviews related to intention models highlighting the need for consideration of normative influences beyond subjective norms (Godin & Kok, 1996; Sheppard et al., 1988).

Indeed, research related to ethical decision making points to the potential significance of behavioral norms. For ex-ample, Ferrell and Gresham (1985) explicitly included the influence from associating or interacting with others who are acting unethically in their model of ethical decision mak-ing. Gibson and Frakes (1997), in exploring unethical deci-sion making by CPAs, included a question as to what other CPAs would do in the situation. Of those reporting ques-tionable conduct, significant percentages also reported they believed others would perform the unethical act. In testing an

intention model, Buchan (2005) included an ethical climate construct that could include the notion of how others within the organization are behaving in situations involving ethical content. This perspective is also consistent with the think-ing of Trevino (1986), who suggested that job context and culture were aspects influencing ethical decision making in organizations. Given the previous discussion, we believe the behavioral norm concept may be particularly relevant to un-derstanding ethical decision making, as individuals are likely to look to the behavior of relevant others in their environment for input regarding appropriate conduct.

Prior efforts to extend the intention models in ethical de-cision contexts have included ethical sensitivity and ethical judgment components of Rest’s (1983) model. The think-ing underlythink-ing such efforts relates to an attempt to inte-grate aspects of moral reasoning theory (Kohlberg, 1969; Rest, 1983) within intention models. Of relevance to the present research are findings that did not support relation-ships between ethical sensitivity and intentions or ethical reasoning (Buchan, 2005; Chan & Leung, 2006). In contrast, Cherry (2006) found a strong relationship between ethical judgment and intention. Justification for the addition of an ethical judgment construct as a proximal antecedent to in-tention in the present research is based on its central role in a number of ethical frameworks (cf. Hunt & Vitell, 1986; Rest, 1983, 1986). Specifically, Hunt and Vitell as well as Cherry placed ethical judgment as an immediate antecedent to intention. Hunt and Vitell’s model conceives of conse-quences and their evaluation and important stakeholders as antecedents to ethical judgments. Similarly, Cherry proposed and found support for attitudinal and normative influence on ethical judgment. Literature related to normative influence in consumer and business contexts has linked its effects to judgment processes (i.e., risk reduction) in decision mak-ing (cf. Bearden, Netemeyer, & Teel, 1989; Cannon, Achrol, & Gundlach, 2000). Therefore, we proposed the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1 (H1): Attitude toward the act would be

sig-nificantly related to the ethical judgment of the act. Specifically, strong (weak) perceptions of negative con-sequences associated with the act would be associated with the judgment of the act as unethical (ethical).

H2: Subjective norm toward the act would be significantly related to the ethical judgment. That is, perceptions that important referents disagree (agree) with the question-able action would be associated with the judgment of the act as unethical (ethical).

H3: Behavioral norm toward the act would be significantly related to the ethical judgment. That is, perceptions that relevant referents do (not) engage in the questionable act would be associated with the judgment of the act as ethical (unethical).

Subjective and behavioral norms should have direct influ-ence on intention. Cherry (2006) found support for the

in-fluence of subjective norms on ethical intention. Behavioral norms have also been found to be independent predictors of intention and behavior (cf. Kashima & Gallois, 1993; Nu-cifora, Gallois, & Kashima, 1993). In addition, the impact of normative influence on the adoption of harmful behavior is well established (cf. Chassin, Presson, Sherman, Corty, & Olsavsky, 1984; Kandel, 1980; McAllister, Krosnick, & Milburn, 1984). Taken together, results point to the direct influence of norms on ethical intention. Therefore, we pro-posed the following hypotheses:

H4: Subjective norm toward the act would be significantly related to the behavioral intention with respect to the ethical act. That is, perceptions that important refer-ents agree (disagree) with the questionable action would be associated with the intention to (not) engage in the act.

H5: Behavioral norm toward the act would be significantly related to the behavioral intention. That is, perceptions that relevant referents do (not) engage in the questionable act would be associated with the intention to (not) engage in the act.

Last, Hunt and Vitell (1986) and Cherry (2006) conceived of ethical judgment as an immediate antecedent to intention. Cherry found a strong relationship between ethical judgment and intention. Therefore, we posited the following hypothe-sis:

H6: The ethical judgment of the act would be significantly related to the behavioral intention. Specifically, the judg-ment of the act as ethical (unethical) would be associated with the intention to (not) engage in the act.

METHOD

Sample and Procedure

Participants were 348 students enrolled in introductory ac-counting classes at a medium-sized Midwestern university. Given that the course is a requirement in the business core, the resultant sample was multidisciplinary in composition. Individuals in each class were randomly assigned one of two ethical scenarios along with a measurement questionnaire. Students were instructed to read the vignette and then to answer the questionnaire.

Ethical scenarios are used extensively in business ethics research (cf. Buchan, 2005; Chonko & Hunt, 1985; Cohen, Pant, & Sharp, 1995, 2001). As a category of stimulus mate-rials, scenarios combine the benefits of standardization and mundane realism (Cherry, 2006). The specific scenarios used in the present study were used in prior ethical research (Co-hen et al., 2001) and are consistent with the TRA, as they portray behaviors under an individual’s volitional control (see Appendix A for scenario descriptions).

204 K. CELUCH AND A. DILL

Measures

Consistent with the proposed model, measures employed in the questionnaire consisted of scales developed specifically for constructs applicable to the act portrayed in each eth-ical scenario. Questionnaires included measures related to attitude toward the act, subjective norm toward the act, be-havioral norm toward the act, ethical judgment of the act, and behavioral intention with respect to the act. In this study we employed multiitem scales for all variables with the excep-tion of intenexcep-tion.

Attitude measures. Attitude toward the act portrayed in Scenario 1 consisted of four 7-point items, with respon-dents providing perceptions of the likelihood of possible out-comes and the corresponding importance of those outout-comes relating to the behavior in the scenario. The outcomes in-cluded that the action may result in legal problems for the company, upset the management of the company, hurt the reputation of the company, and hurt the actor’s reputation. Attitude toward the act portrayed in Scenario 2 consisted of three 7-point items and followed the format used for Sce-nario 1. The outcomes included that the action may upset other employees at the company, upset the management at the company, and hurt the reputation of the salesperson.

Subjective norm measures. The subjective norm to-ward the act portrayed in Scenario 1 consisted of three 7-point items, with respondents providing perceptions of the likelihood of important referents agreeing with the action and respondents’ corresponding motivation to comply with each referent’s view. Referents included employees in the com-pany, friends, and family. The subjective norm toward the act portrayed in Scenario 2 consisted of three 7-point items and followed the format used for Scenario 1. Referents included salespeople in the company, friends, and family.

Behavioral norm measures. The behavioral norm to-ward the act in Scenario 1 consisted of three 7-point items, with respondents providing perceptions relating to most other employees in the department, other departments, and other companies undertaking the same action as the actor in the scenario. The behavioral norm toward the act in Scenario 2 consisted of three 7-point items, with respondents providing perceptions relating to most other salespeople in the com-pany, other companies, and other industries undertaking the same action as the actor in the scenario.

Ethical judgment measure. The ethical judgment of the act consisted of three 7-point items, with respondents providing perceptions relating to the justness, fairness, and moral acceptability of the actor’s behavior (adapted from the work of Cohen et al., 2001).

Intention measure. Behavioral intention with respect to the act consisted of one 7-point item relating to the extent a respondent would undertake the same action as the actor in the scenario.

RESULTS

The objective of the present research was to test a model ex-amining relationships among TRA, behavioral norm, and eth-ical judgment constructs for each scenario. Structural equa-tion modeling was employed for model evaluaequa-tion. As rec-ommended, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was used to assess the convergent and discriminant validity of the mul-tiitem measures before testing hypotheses. With respect to the measurement models, observed indicators were all sta-tistically significant and evidenced large loadings on their corresponding factors. Fit statistics of the measurement mod-els suggested reasonable fit between observed indicators and constructs, for Scenario 1,χ2(94,N=175)=108.283,p=

.000, goodness of fit index (GFI)=.910, adjusted goodness of fit index (AGFI)=.861, comparative fit index (CFI) = .965, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA)= .069; for Scenario 2,χ2(80,N =173)=93.274,p=.000,

GFI=.922, AGFI=.874, CFI=.968, RMSEA=.074. Pairwise CFA was conducted to assess discriminant va-lidity of the measures. For each pair of measures, across both scenarios, trying to force the measures of different constructs into a single underlying factor led to a significant deteriora-tion of model fit in comparison to the two-factor model. These results provide support for the discriminant validity of the measures (Anderson & Gerbing, 1988).

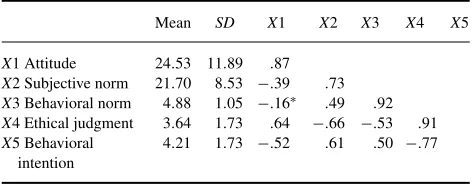

Based on measurement model results, composite scores of the multiitem scales were used to address the research hy-potheses. Specifically, all matched likelihood and importance items were multiplied together, summed, and divided by the number of paired items to form an overall attitude toward the act. Similarly, all matched likelihood and motivation to comply items were multiplied together, summed, and then divided by the number of paired items to form an overall subjective norm toward the act. Items related to behavioral norms and ethical judgment were summed and averaged. Tables 1 and 2 provide the means, standard deviations, cor-relations, and reliabilities for the multiitem measures used in this study.

As noted previously, structural equation modeling was employed for model evaluation. The results of estimating the hypothesized model are presented in Tables 3 and 4. Estimation of the model for each scenario resulted in a good fit of the model to the data, for Scenario 1,χ2(2,N=175)=

2.589, p =.108, GFI =.994, AGFI=.912, CFI =.995, RMSEA=.096; for Scenario 2,χ2(2,N=173)=2.108,p=

.147, GFI=.995, AGFI=.927, CFI=.997, RMSEA=.080. In addition, five of six hypothesized paths were statistically significant in each model and in the predicted direction.

TABLE 1

Descriptive Statistics, Correlations and Reliabilities for Model Constructs for Scenario 1

Mean SD X1 X2 X3 X4 X5 X1 Attitude 28.75 12.21 .90

X2 Subjective norm 17.04 8.04 −.41 .79

X3 Behavioral norm 3.94 1.14 −.40 .49 .91

X4 Ethical judgment 4.48 1.42 .60 −.57 .38 .81

X5 Behavioral intention

3.78 1.61 −.47 .54 .44 −.58

All correlations significant atp<.01

Consistent with expectations, attitude toward the act was found to be significantly related to the ethical judgment of the act for each scenario. As expected, the subjective norm to-ward the act was found to be significantly related to the ethical judgment as well as intention for both scenarios. Behavioral norm toward the act was found to be significant for one of two expected paths, with a significant relationship found with behavioral intention for Scenario 1 and a significant relation-ship found with ethical judgment for Scenario 2. Contrary to expectations, behavioral norm was not significantly related to ethical judgment for Scenario 1 and behavioral intention for Scenario 2. Last, as anticipated, the ethical judgment was found to be significantly related to behavioral intention for each scenario.

DISCUSSION

The present study extends the understanding of ethical de-cision making by exploring relationships among traditional TRA constructs and additional constructs. Specifically, we examined a model that included an expansion of norma-tive influence to include a behavioral norm and an ethical judgment construct as proximal to intention. To our knowl-edge, these relationships have not been simultaneously ex-plored in the business ethics literature. As noted previously, the moral conduct of organizations is ultimately dependent

TABLE 2

Descriptive Statistics, Correlations, and Reliabilities for Model Constructs for Scenario 2

Mean SD X1 X2 X3 X4 X5 X1 Attitude 24.53 11.89 .87

X2 Subjective norm 21.70 8.53 −.39 .73

X3 Behavioral norm 4.88 1.05 −.16∗ .49 .92

X4 Ethical judgment 3.64 1.73 .64 −.66 −.53 .91

X5 Behavioral intention

4.21 1.73 −.52 .61 .50 −.77

All correlations significant atp<.01 unless otherwise noted

“∗” Significant atp <.05

TABLE 3

Standardized Path Coefficients andt-Values for Model Relationships and Model Fit Statistics for

Scenario 1

Standardized

coefficient t-value Attitude to ethical judgment .44 7.09

Subjective norm to ethical judgment −.39 −5.95

Behavioral norm to ethical judgment −.01 −.13

Subjective norm to behavioral intention .24 3.13

Behavioral norm to behavioral intention .18 2.71 Ethical judgment to behavioral intention −.38 −5.35

χ2(2,N=175)=2.589.p=.108. GFI=.994. AGFI=.912. CFI=

.995. RMSEA=.096.

on the discrete actions of individuals. Thus, we addressed the scholarly and managerial imperative of how individ-uals combine various cognitions in their ethical decision making.

Summarizing significant findings that were observed for both scenarios, attitude toward a questionable act, composed of perceptions of negative consequences was significantly related to the ethical judgment, that is, a negative judgment of the act. Subjective norm toward the act was significantly related to the ethical judgment such that perceptions that important referents disagreed with the act were associated with a negative judgment of the act and a weaker intention to engage in the act. The ethical judgment of the act was significantly related to the behavioral intention such that a negative judgment of the act was related to a weaker intention to engage in the act.

With respect to the addition of an ethical judgment con-struct to the TRA model, in the present study, ethical judg-ment was found to be a strong predictor of intention, which is consistent with results reported by Cherry (2006). It would appear that the inclusion of an ethical judgment construct in models examining ethical intention would be worthwhile as

TABLE 4

Standardized Path Coefficient andt-Values for Model Relationships and Model Fit Statistics for

Scenario 2

Standardized

coefficient t-value Attitude to ethical judgment .46 9.72 Subjective norm to ethical judgment −.33 −6.09

Behavioral norm to ethical judgment −.29 −5.68

Subjective norm to behavioral intention .17 2.56

Behavioral norm to behavioral intention .10 1.73

Ethical judgment to behavioral intention −.60 −9.14 χ2(2,N=173)=2.108.p=.147. GFI=.995. AGFI=.927. CFI=

.997. RMSEA=.080.

206 K. CELUCH AND A. DILL

a means of integrating an aspect of moral reasoning theory (Kohlberg, 1969; Rest, 1983) with the TRA orientation.

Although the influence of the behavioral norm construct was found to be significant in each model, results were mixed in that it worked differently for the scenarios. For Scenario 1, behavior norm toward the questionable act was significantly related to the behavioral intention, such that perceptions that relevant referents engage in the act were associated with a stronger intention to engage in the act. For Scenario 2, be-havioral norm toward the questionable act was significantly related to the ethical judgment such that perceptions that relevant referents engage in the act were related to a posi-tive judgment of the act. Perhaps the fact that one scenario (Scenario 2) includes an explicit reference to this type of nor-mative influence whereas the other scenario does not might account for these differences. Owing to the identification of indirect and direct effects for the behavioral norm on inten-tion, future TRA researchers should explore the extent of the influence for different scenarios and samples of respondents. As with any study employing cross-sectional, single time period data collection, results should be interpreted with this limitation in mind. A multidisciplinary student sample was used, which is appropriate for inferences regarding students and entry-level employees; however, experienced workers in corporate settings may respond differently. Although the key outcome variable used in this study and many others, be-havioral intention, is appropriate for testing the TRA, future researchers should include actual behavior. Of course, exam-ining actual unethical behavior raises additional issues in the conduct of the research.

Implications

From a practical standpoint, the TRA provides leverage points from which to affect intention and behavior. Recall that attitude toward the act was a strong predictor of ethical judgment. Thus, persuasive communications aimed at the potential negative consequences of unethical behavior could prove useful in strengthening judgments of questionable ac-tions. Note, however, that reliance on persuasive communi-cation exclusively as is used in many classes and company workshops, although addressing attitudes, addresses only one component of the model that indirectly influences intention through its impact on the ethical judgment.

Norms were also found to significantly exert indirect and direct influence on intentions. Sharing important others per-spectives appears to be relevant for encouraging ethical con-duct. However, note that the influence of norms may affect the ethical judgment or the intention. Sharing this insight with students so that they are aware of the dual influence is consistent with metacognitive approaches to improve think-ing and learnthink-ing. Further, note the distinction highlighted in the present research between what significant others say (subjective norm) and what they do (behavioral norm). Thus, care must be taken that behavioral norms are not working

at cross-purposes with subjective norms, as in the case in which peer employees are behaving unethically in the pres-ence of pronouncements from top management regarding proper conduct. This scenario argues for addressing the role of ethics in organizational culture development and main-tenance. For example, addressing alignment issues among corporate policies and what leaders emphasize (i.e., what is said) and role modeling and coaching used by supervisors and criteria for allocating resources and rewards (i.e., aspects of organizations that can influence what people do) as they relate to ethical conduct would prove beneficial.

In conclusion, how individuals make (un)ethical decisions continues to be a significant topic for business researchers and practitioners. This research addresses some conceptual issues in relationships among TRA-relevant constructs and, in doing so, adds depth to the understanding of ethical in-tentions. It is hoped that the present theory-driven approach contributes to future empirical efforts aimed at developing a more nuanced understanding of how individuals combine various cognitions related to ethical decision making.

REFERENCES

Ajzen, I. (1985). From intentions to actions: A theory of planned behavior. In J. Kuhl & J. Beckman (Eds.),Action control: From cognition to behavior (pp. 11–39). Berlin, Germany: Springer-Verlag.

Ajzen, I. (1988).Attitudes, personality, and behavior. Chicago, IL: Dorsey Press.

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior.Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes,50, 179–211.

Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M. (1980).Understanding attitudes and predicting social behavior. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Anderson, J. C. (1997). What cognitive science tells us about ethics and the teaching of ethics.Journal of Business Ethics,16, 279–291.

Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach.Psychological Bulletin,103, 411–423.

Bearden, W. O., Netemeyer, R. G., & Teel, J. E. (1989). Measurement of consumer susceptibility to interpersonal influence.Journal of Consumer Research,15, 473–481.

Buchan, H. F. (2005). Ethical decision making in the public accounting profession: An extension of Ajzen’s theory of planned behavior.Journal of Business Ethics,61, 165–181.

Cannon, J. P., Achrol, R. S., & Gundlach, G. T. (2000). Contracts, norms, and plural form governance.Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 28, 180–194.

Carpenter, T. C., & Reimers, J. L. (2005). Unethical and fraudulent financial reporting: Applying the theory of planned behavior.Journal of Business Ethics,60, 115–129.

Chan, S. Y., & Leung, P. (2006). The effects of accounting students’ ethical reasoning and personal factors on their ethical sensitivity.Managerial Auditing Journal,21, 436–457.

Chassin, L., Presson, C. C., Sherman, S. J., Corty, E., & Olsavsky, R. (1984). Predicting the onset of cigarette smoking in adolescents: A longitudinal study.Journal of Applied Social Psychology,14, 224–243.

Cherry, J. (2006). The impact of normative influence and locus of control on ethical judgments and intentions: A cross-cultural comparison.Journal of Business Ethics,68, 113–132.

Chonko, L. B., & Hunt, S. D. (1985). Ethics and marketing management: An empirical Examination.Journal of Business Research,13, 339–359.

Cohen, J. R., Pant, L. W., & Sharp, D. J. (1995). An international comparison of moral constructs underlying auditors’ ethical judgments.Research on Accounting Ethics,1, 97–126.

Cohen, J. R., Pant, L. W. & Sharp, D. J. (2001). An examination of differences in ethical decision-making between Canadian business stu-dents and accounting professionals.Journal of Business Ethics,30, 319– 335.

Conner, M., & Armitage, C. J. (1998). Extending the theory of planned behavior: A review and Avenues for further research.Journal of Applied Social Psychology,28, 1429–1464.

Dubinsky, A. J., & Loken, B. (1989). Analyzing ethical decision making in marketing.Journal of Business Research,19, 83–107.

Eagly, A. H., & Chaiken, S. (1993).The psychology of attitudes. Fort Worth, TX: Harcourt Brace.

Ferrell, O. C., & Gresham, L. G. (1985). A contingency framework for un-derstanding ethical decision making in marketing.Journal of Marketing, 49, 87–96.

Fishbein, M. (1993). Introduction. In D. J. Terry, C. Gallois, & M. McCamish (Eds.),The theory of reasoned action: Its application to AIDS-preventive behavior(pp. XV–XXV). Oxford, England: Pergamon.

Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (1975).Belief, attitude, intention, and behav-ior: An introduction to theory and research. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Gibson, A. M., & Frakes, A. H. (1997). Truth of consequences: A study of critical issues and decision making in accounting.Journal of Business Ethics,16, 161–171.

Godin, G., & Kok, G. (1996). The theory of planned behavior: A review of its applications to health-related behaviors.American Journal of Health Promotion,11, 87–98.

Haytko, D. L. (2004). Firm-to-firm and interpersonal relationships: Perspec-tives from advertising agency account managers.Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science,32, 313–327.

Hunt, S. D., & Vitell, S. (1986). General theory of marketing ethic.Journal of Macromarketing. Spring, 5–16.

Kandel, D. B. (1980). Drug and drinking behavior among youth.Annual Review of Sociology,6, 235–285.

Kashima, Y., & Gallois, C. (1993). The theory of reasoned action and problem-focused Research. In D. J. Terry, C. Gallois, & M. McCamish (Eds.),The theory of reasoned action: Its application to AIDS-preventive behavior(pp. 207–226). Oxford, England: Pergamon.

Kohlberg, L. (1969). Stages and sequences: The cognitive development ap-proach to Socialization. In D. A. Goslin (Ed.),Handbook of socialization theory and research(pp. 346–480). Chicago, IL: Rand McNally. Legace, R. R., Dahlstrom, R., & Gassenheimer, J. (1991). The relevance of

ethical salesperson behavior on relationship quality: The pharmaceutical industry.The Journal of Personal Selling & Sales Management,11(4), 39–47.

McAllister, A. L., Krosnick, J. A., & Milburn, M. A. (1984). Causes of adolescent cigarette smoking: Tests of a structural equation model.Social Psychology Quarterly,47, 24–36.

Nucifora, J., Gallois, C., & Kashima, Y. (1993). Influences on condom use among undergraduates: Testing the theories of reasoned action and planned behavior. In D. J. Terry, C. Gallois, & M. McCamish (Eds.),The theory of reasoned action: Its application to AIDS- preventive behavior (pp. 41–64). Oxford, England: Pergamon.

Rest, J. R. (1983). Morality. In J. Flavell & E. Markman (Eds.),Handbook of child psychology(Vol. III, 4th ed., pp. 556–628). New York, NY: Wiley. Rest, J. R. (1986).Moral development: Advances in research and theory.

New York, NY: Praeger.

Sheppard, B., Hartwick, J., & Warshaw, P. (1988). The theory of reasoned action: A meta analysis of past research with recommendations for modifi-cations and future research.Journal of Consumer Research,15, 325–343. Trevino, L. K. (1986). Ethical decision-making in organizations: A person-situation interactionist model.Academy of Management Review,July, 601–617.

APPENDIX A

ETHICAL SCENARIOS

Scenario 1

The owner of a small business, which is currently in financial difficulty, approaches a longtime friend to borrow and copy a copyrighted database software package which will be of great help in generating future business. The longtime friend is a manager of an IT department and can borrow the software from his or her own company. The friend loans the software package.

Scenario 2

A salesperson, the parent of two children, has been pro-moted to a job in which frequent travel away from home is required by the company. Because the trips are frequent and inconvenience the salesperson’s family, the salesperson is considering charging some small personal expenses while traveling for the company. The salesperson has heard that this is a common practice among other salespersons.