Tribes of Idukki, Kerala

Researched and compiled by

Bijumon Varghese and Jose P. Mathew

SIL International

®2015

SIL Electronic Survey Report 2015-029, December 2015 © 2015 SIL International®

Abstract

This sociolinguistic survey of selected Scheduled Tribes in the Idukki district of Kerala was sponsored and carried out by the Indian Institute for Cross-Cultural Communication (IICCC), which is interested in developing mother tongue literature and promoting literacy among the minority people groups of India. This report tells about the social and unique linguistic features exhibited by the different tribes found in Idukki district. The project started in December 2001 and fieldwork was finished by the middle of May 2002. The report was written in October 2002.

iii

Contents

1 Introduction

1.1 Geography

1.2 People

1.3 Languages

1.4 Purpose and goals

2 Tribes of Idukki

2.1 Introduction

2.2 Muthuvan

2.2.1 Geography

2.2.2 History

2.2.3 People

2.2.4 Language

2.3 Mannan

2.3.1 Geography

2.3.2 History

2.3.3 People

2.3.4 Language

2.4 Mala Arayan

2.5 Urali

2.6 Ulladan

2.7 Mala Pulayan

2.8 Paliyan

2.9 Mala Vedan

2.10Mala Pandaram

3 Dialect areas

3.1 Lexical similarity

3.1.1 Procedures

3.1.2 Site selection

3.1.3 Results and analysis

3.1.4 Conclusion

3.2 Intelligibility testing

3.2.1 Procedures

3.2.2 Site selection

3.2.3 Intelligibility testing results and analysis

3.2.4 Conclusion

4 Language use, attitudes and vitality

4.1 Procedures

4.2 Sampling distribution for questionnaire subjects

4.3 Muthuvan questionnaire results and analysis

4.3.1 Language use

4.3.2 Language attitude

4.3.3 Language vitality

4.4 Observations and informal interviews

4.5 Conclusion

4.6 Mannan questionnaire results and analysis

4.6.1 Language use

4.6.2 Language attitudes

4.6.3 Language vitality

4.7 Observations and informal interviews

5 Bilingualism

5.1 Introduction

5.2 Recorded Text Test

5.2.1 Procedure

5.2.2 Site selection

5.2.3 Results

5.3 Self-reported bilingualism in Malayalam

5.3.1 Questionnaire procedures

5.3.2 Demographic profiles

5.3.3 Muthuvan questionnaire results

5.3.4 Mannan questionnaire results

5.4 Observations of community bilingualism

5.4.1 Muthuvan

5.4.2 Mannan

5.5 Conclusion

6 Summary of Findings

6.1 Muthuvan

6.1.1 Lexical similarity study

6.1.2 Dialect intelligibility

6.1.3 Bilingualism study

6.1.4 Language use, attitudes and vitality study

6.2 Mannan

6.2.1 Lexical similarity study

6.2.2 Dialect intelligibility

6.2.3 Bilingualism study

6.2.4 Language use, attitudes and vitality study

7 Recommendations

7.1 Muthuvan

7.1.1 For literature development

7.1.2 For literacy work

7.2 Mannan

7.2.1 For language development

7.2.2 For literacy work

7.3 Other tribal groups

7.3.1 Mala Arayan

7.3.2 Urali

7.3.3 Ulladan

7.3.4 Mala Pulayan and Paliyan

7.3.5 Mala Vedan and Mala Pandaram

Appendix A: International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) Appendix B: Wordlists

Appendix C: Recorded Text Test (RTT)

Appendix D: Language Use, Attitude and Vitality questionnaires (LUAV)

Appendix E: Village Information Questionnaires (VIQ) and Language Information Questionnaires (LIQ)

1

1 Introduction

1.1 Geography

Idukki, one of the largest districts in Kerala, is politically divided into four tahsils1 (Devikulam,

Udumpanchola, Pirmed and Thodupuzha), eight blocks, 51 panchayats2 and 64 villages. This charming

district is flanked by the Western Ghats and is bounded by Trissur district of Kerala and Coimbatore district of Tamil Nadu in the north, Madurai and Ramanathapuram districts of Tamil Nadu in the east, Pathanamthitta district of Kerala in the south and Kottayam and Ernakulam districts of Kerala in the west. The district headquarters is located in Painavu.

Idukki, the most mountainous district of Kerala, gets its name from the Malayalam word ‘Idukku’, which means ‘a narrow gorge.’ The district consists of majestic mountains and green valleys. About 1,500 square kilometres of reserved forest area is a sanctuary for charming wildlife and unusual plants. Anaimudi, the highest peak of southern India, is found in Idukki. A landlocked district, Idukki is one of the most nature-rich areas of Kerala. Three main rivers (Periyar, Thalayar and Thodupuzhayar) and their tributaries gird high ranges and wooded valleys. The river Pamba also has its origin here. The area is also famous for hill resorts and the Periyar Wildlife Sanctuary. The natural sandalwood forest sanctuary of Kerala is in Idukki.

Idukki is an industrially undeveloped district. It has no air or rail connections. Tea production is the main industry of the district. Besides that pepper, coffee, cardamom, and rubber are the most important commodities produced in and exported from Idukki. Map 1 displays the location of Idukki district.

Map 1. Location of Idukki District

Source: Includes geodata from www.worldgeodatasets.com and Esri. Used with permission.

1 A tahsil is a district administration in India (“tahsill.” Merriam-Webster.com. 2015.

http://www.merriam-webster.com (10 March 2016)).

2 A panchayat is a village council in India (“panchayat.” Merriam-Webster.com. 2015.

1.2 People

The inhabitants of Idukki district have migrated there at different times. Several tribal groups, as well as people from the plains, are found in Idukki. It is believed that the tribal groups migrated from Tamil Nadu and other parts of Kerala in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. The Europeans entered the area during the first decades of the nineteenth century and started tea plantations. A major migration of people from the plains (Tamil Nadu and other parts of Kerala) to this area occurred between 1950 and 1970 (Manoj 2001:40). Many of those migrants came and settled as cultivators and estate laborers.

According to the 2001 census, the total population of Idukki district is 1,128,605 with a literacy rate of 89%. The people profess Hinduism, Christianity, Islam and tribal (animistic) religions. The 1981 census records about half of the population as Hindu, about 40% as Christian, and a small minority as Muslim.

Idukki has a large population of tribal people who belong to the Proto-astroloid race (Manoj 2001:40). It appears that only a few of Idukki’s tribal communities are keeping their ethnic uniqueness vital. Education has brought many changes into the lives of these tribes. Their cultures and languages have been very much influenced by migrants from the plains.

1.3 Languages

Malayalam, Tamil and several tribal languages are spoken in Idukki district. Malayalam is the language of wider communication. Some of the tribal groups, such as Muthuvan and Mannan, still speak their languages among themselves. However, education in Malayalam and frequent contact with Malayalis may eventually cause, or be in the process of causing, language shift in some other tribal groups. It appears that language shift has taken or is taking place towards Malayalam among the Mala Arayan, Ulladan and Urali. It is believed that the younger generation among these groups does not know about their group’s traditional language and may only know a few words. The Mala Pulayan and Paliyan are believed to speak languages related to Tamil, but conversely with others in Malayalam or Tamil. One member among the Mala Vedan in Idukki has reported that they have not spoken their traditional language since they emigrated from their original home area. Menon (1996:141) reports that the language of the Mala Pandaram is a mixture of Tamil and Malayalam.

1.4 Purpose and goals

The purpose of this sociolinguistic survey among the tribes of Idukki district of Kerala was to investigate the need for language development and literacy work among them for the welfare of the community.

The goals of the project, along with the research methods used, were:

1. Investigate the speech varieties currently spoken among the tribes of Idukki and their relationship with the languages of wider communication, Malayalam and Tamil. (Wordlists, published materials and questionnaires)

2. Assess the degree of variation within each speech variety of Idukki district. (Wordlists, Recorded Text Test (RTT) and questionnaires)

3. Evaluate the extent of bilingualism among minority language communities in Kerala’s state language, Malayalam. (Malayalam RTT, questionnaires and observation)

5. Ascertain the difference between the scheduled tribe and scheduled caste3 Mannan in terms of

language and people. (Wordlists, published materials and questionnaires) 6. Find out what materials are available about the tribal groups of Idukki district.

(Questionnaires and library research)

2 Tribes of Idukki

2.1 Introduction

People of different tribal groups live in Idukki district. The 1991 census listed the population of 30 different tribal groups in Idukki. However, 16 of these groups have less than 100 people. According to the reports of the Integrated Tribal Development Programme (ITDP), nine major tribal groups are found here. The largest tribes are the Mala Arayan, Muthuvan, Mannan, Urali, Ulladan, Paliyan and Mala Pulayan. Mala Vedan and Mala Pandaram are also found in Idukki, but their population is much smaller than that of the other groups. The Muthuvan, Mannan, Paliyan and Mala Pulayan are culturally related to groups in Tamil Nadu. The Urali, Ulladan and Mala Arayan appear to have migrated to Idukki from other parts of Kerala.

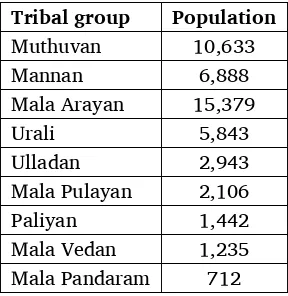

Table 1 shows the major tribal populations of Idukki district according to the 1991 census.

Table 1. Tribal populations of Idukki district

Tribal group Population

Muthuvan 10,633

Mannan 6,888

Mala Arayan 15,379

Urali 5,843

Ulladan 2,943

Mala Pulayan 2,106

Paliyan 1,442

Mala Vedan 1,235

Mala Pandaram 712

2.2 Muthuvan

2.2.1 Geography

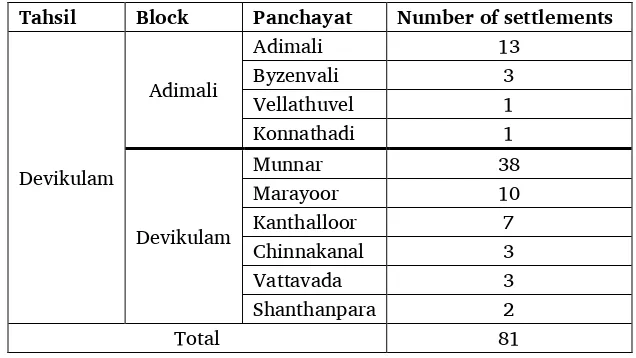

The Muthuvan primarily live in Devikulam and Adimali blocks in Devikulam tahsil of Idukki district. There are also some communities that reside in the adjoining area of Udumalpet and Valparai tahsils of Coimbatore district of Tamil Nadu. Since the recent partition of Idukki district, there are also some settlements in Ernakulam district of Kerala. Muthuvan settlements are often situated on hill slopes at elevations ranging from 3,000 to 6,000 feet MSL in thick forests. A number of Muthuvan settlements are scattered around Anaimudi, the highest peak in southern India (Singh 1994:833–834). Table 2 shows the number of settlements in each tahsil:

3 “The Scheduled Castes (SCs) and Scheduled Tribes (STs) are official designations given to various groups of

historically disadvantaged people in India.” (‘scheduled castes and scheduled tribes.’

Table 2. Distribution of Muthuvan settlements in Idukki district

Tahsil Block Panchayat Number of settlements

Devikulam

Adimali

Adimali 13

Byzenvali 3

Vellathuvel 1

Konnathadi 1

Devikulam

Munnar 38

Marayoor 10

Kanthalloor 7

Chinnakanal 3

Vattavada 3

Shanthanpara 2

Total 81

2.2.2 History

According to a legend prevalent among the Muthuvan, cited by Thurston (1909:86–103), they originally belonged to Madurai in Tamil Nadu. When Kannagi, a divine woman and the principle character of the Tamil epic Chilappathikaram left Madurai after destroying it by her curse, a group of people also migrated with her to the hills, carrying her, their children and belongings on their backs (muthuku, in Malayalam). Thus they came to be known as Muthuvan, meaning ‘those who carried something on their backs’. The Muthuvan still carry their children on their backs, an uncommon practice in Kerala.

According to another version, the name is derived from the word mutu, which means ‘old’ (Singh 1994:833).

2.2.3 People

Muthuvan is also spelled ‘Muduvan’ by some writers. But, in this report, the spelling ‘Muthuvan’ will be used. This group should not be confused with ‘Mudugar’, an entirely different group in Palakkad, Kerala.

Muthuvan is classified as a scheduled tribe of Kerala and Tamil Nadu. They are one of the most undeveloped people groups in Idukki. Many Muthuvan people can be considered as being part of one of two groups, which may be referred to as Tamil Muthuvan or Malayalam Muthuvan. Some Malayalam Muthuvan also refer to themselves as Nattu Muthuvan and to the Tamil Muthuvan as Pandi Muthuvan, although this may be a derogative term. The differences between the groups are mainly due to contact with Malayalam-speaking people and Tamil-speaking people. They considered themselves as different until a few years ago. However, many of them now realise that they are a part of the same ethnic group, with some differences in their language and customs. More recently, inter-marriage has been taking place and the people have recognised that they share some common interests. But some Muthuvan are still strongly opposed to people from the other Muthuvan subgroups.

2.2.3.1 Population

The 1991 census of India records that there are 10,633 Muthuvan people living in Idukki district. It also reports a total of 437 Muthuvan people in Tamil Nadu. Although the population of Muthuvan, Mudugar and Muduvan was reported together in the 1991 census, the Mudugar are not in Idukki. Therefore, it can be concluded that this number represents the actual Muthuvan population of Idukki. The list of

2.2.3.2 Education

Muthuvan is one of the most educationally undeveloped tribal groups in Idukki district. The literacy rate among the Muthuvan is 24% (31% among males and 17% among females) according to the 1991 census. They have recently begun sending their boys to school, whereas the girls are generally not encouraged to do so. Most Muthuvan settlements are located deep within thickly forested areas. There are a few single-classroom primary schools located in interior settlements. However, most children have to stay in tribal hostels in order to attend classes. But many children are reluctant to be separated from their parents and village for very long.

2.2.3.3 Settlements

There are 81 Muthuvan settlements in Idukki district. Another ten settlements are located in adjoining parts of Tamil Nadu. Of these 91 settlements, 79 are Tamil Muthuvan and only 12 settlements are Malayalam Muthuvan. Malayalam Muthuvan settlements are only found in Kerala. The Tamil Muthuvan tend to live in clusters and the Malayalam Muthuvan are spread throughout the cultivable land. The Muthuvan huts are made of reed and thatched with leaves. The people use a “dormitory system”, in which all the bachelors sleep together in one shelter and all the bachelorettes in another. They are not permitted to sleep in their parents’ hut after they have attained the age of about ten (Menon 1996:288).

2.2.3.4 Social life

The people practice horticulture and slash and burn cultivation in the reserve forests. Cardamom and lemon grass oil are produced and then sold through licensed contractors. The Muthuvan are proficient in weaving baskets and mats. Hunting and fishing traps are made of reed. Wage labour in the forest

department and the collection of seasonal forest produce are subsidiary occupations.

The Muthuvan once followed a tribal religion. They now profess Hinduism, worshipping Murugan, Subramaniar and Ramar. In addition to the deities of the wider pantheon order, they also worship evil deities like Karuppa Swami and Mariyamma. Some Muthuvan families have become Christians.

Ragi is traditionally their staple food, although it is being supplanted by rice and tapioca. The Muthuvan men wear ear-studs, white dhotis and turbans. The women wear their saris in such a way that a pouch is made on their back, which they use to carry their babies.

There are several clans among the Muthuvan, including the Mela Kuttam, Kana Kuttam, Susana Kuttam and Puthani Kuttam. The headman (kanikaran) of a settlement is elected by the members of that settlement, irrespective of his clan or lineage. Any members of the community that commit adultery, theft or break traditional norms are punished by the imposition of cash fines or are excommunicated. They strictly adhere to community endogamy, only allowing marriage between members of the same group.

2.2.4 Language

2.3 Mannan

2.3.1 Geography

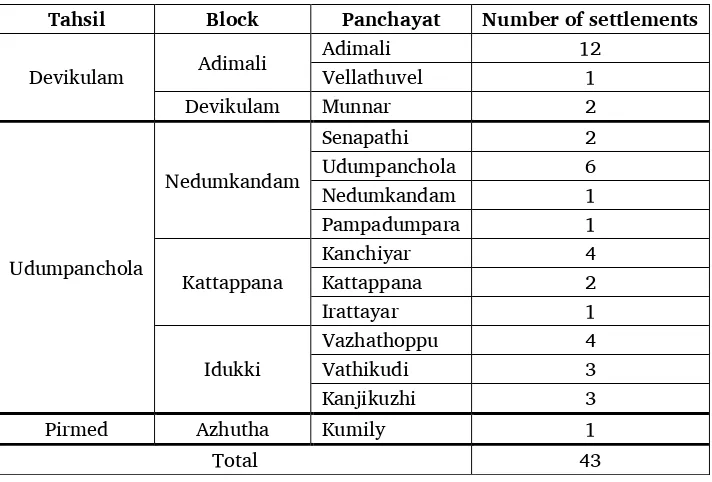

The Mannan are found in Udumpanchola, Devikulam and Pirmed tahsils of Idukki district. Their

settlements are scattered throughout this area. A few settlements can also be found in Madurai district of Tamil Nadu. There are many hills and streams in the area and most of the settlements are within forest areas. The Mannan are dependent upon the forests for their livelihood throughout the year. At one time, the settlements were completely remote and had no contact with outsiders, but that has now changed. Many of their villages are located at around 1,000 meters above sea level. The southwest monsoon commences in their area by the end of May, with maximum precipitation falling in June and July. The northeast monsoon arrives in September. Average yearly rainfall is about 250 centimetres (Menon 1996:254). Table 3 shows the number of settlements in each tahsil.

Table 3. Distributions of Mannan settlements in Idukki district

Tahsil Block Panchayat Number of settlements

Devikulam Adimali

Adimali 12

Vellathuvel 1

Devikulam Munnar 2

Udumpanchola

Nedumkandam

Senapathi 2

Udumpanchola 6

Nedumkandam 1

Pampadumpara 1

Kattappana

Kanchiyar 4

Kattappana 2

Irattayar 1

Idukki

Vazhathoppu 4

Vathikudi 3

Kanjikuzhi 3

Pirmed Azhutha Kumily 1

Total 43

2.3.2 History

According to Thurston (1909:452–455), Mannan is a hill tribe of Travancore. The Mannan are reported to be the descendents of the kings of Madurai, whom they accompanied to Neriya Mangalam. According to the myths and legends prevalent among the Mannan, they have migrated to their present region from Madurai in Tamil Nadu. The hills in the Travancore region abounded with vegetation, wild animals and birds when compared to their original Madurai home. It was the quest for food that led them to migrate to the Cardamom Hills. In Menon (1996:254), Iyer reports that based on one story popular among them, “They were formerly the dependants of the kings of Madurai. They entered the Cardamom Hills through Cumbum Mettu and settled there.”

2.3.3 People

means ‘earth’ in Malayalam) and ‘manushian’ (which means ‘man’ in Malayalam): ‘sons of the soil’. According to people’s perception, the term ‘mannan’ means ‘the leaders of the hill’. In physical

appearance, most Mannan people are short statured, have short noses, thick lips and black eyes (Menon 1996:254).

Mannan [mʌnnan] is classified as a scheduled tribe of Kerala and Tamil Nadu. They should not be

confused with Mannan [mʌɳɳan], a scheduled caste that lives in Trivandrum and other adjoining

districts of Kerala and Tamil Nadu.

2.3.3.1 Population

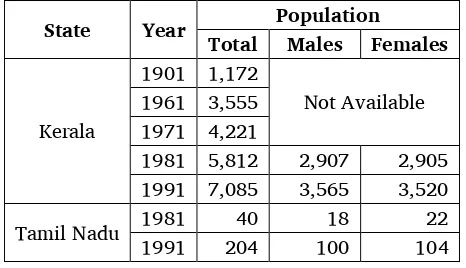

According to the Census Bureau of India, the population of Mannan in Kerala has increased from 1,172 people in 1901 to 7,085 in 1991 (see table 4). The 1991 census also reports that in 1991 there were 204 Mannan living in Tamil Nadu.

Table 4. Population of Mannan throughout the decades

State Year Population

Total Males Females

Kerala

1901 1,172

Not Available 1961 3,555

1971 4,221

1981 5,812 2,907 2,905

1991 7,085 3,565 3,520

Tamil Nadu 1981 40 18 22

1991 204 100 104

2.3.3.2 Education

Some of the Mannan boys study up to tenth class, whereas many girls only study up to fourth class. Many of the children discontinue their studies due to the lack of secondary schools in their locality and due to economic problems (Singh 1994:755). The children of interior settlements can make use of tribal hostels in their area, but many do not do so. There have recently been some graduates among them. The literacy rate of Mannan is 35% according to the 1991 census (41% among men and 30% among women).

2.3.3.3 Settlements

There are 46 settlements of Mannan in Idukki district. The Mannan live in small groups of families called

kudi (village). Level space at high elevation is preferred as the sites for their hamlets. The size of the

village depends on the availability of the food supply (Shashi 1994:290). In Menon (1996:255) Iyer reported that they were once nomadic agriculturalists. Some settlements consist of 50 to 60 huts in a cluster; others may have as few as 10 to 15.

2.3.3.4 Social life

They eat buffalo meat, but not beef. Their staple foods are ragi, rice, roots and tubers. Pulses like gram, tur, peas and beans are also part of their diet. They consume alcohol, but avoid cow’s milk.

Mannan women participate in social, ritual and religious activities along with the men. They also contribute to the family income. Although inter-caste marriage now occurs, the couples are restricted to living inside their settlement.

The Mannan have modified their animistic practices towards those of orthodox Hinduism. The Mannan mother goddess ‘Kanchiyar Mutthi’ is their most important deity. She is now believed to be the younger sister of the popular Hindu goddess Madura Meenakshi. Pongal, Makaravilakku and Kanjiveppu are the major festivals for the Mannan.

The Raja Mannan is their ruler. He is assisted by a traditional council of ministers. Each settlement

has a kani, or kanikaran (headman). The Integrated Tribal Development Programme (ITDP) and ‘Akhila

Kerala Mannan Samudaya Sangam’ (an association of Mannan headed by Raja Mannan) are involved in various development programmes in the community.

2.3.4 Language

There are different opinions about the nature of the Mannan language. According to Thurston

(1909:452–455), the language of Mannan is Tamil. Singh (1994:754) has said that they speak a dialect of Tamil, but converse with others in Malayalam and use the Malayalam script. It has also been said that the people of Mannan speak a dialect of Tamil and Malayalam with a very peculiar accent and that, when they converse, it is difficult to understand (Sachchidananda 1996).

Despite these reports, Mannan have their own speech variety, known as ‘Inavan petch’. Outsiders refer to it as ‘Mannan Pasha’. Although Malayalam and Tamil may have influenced the language, it is different enough that it is difficult for outsiders to understand. The linguistic classification of their variety is with Southern Dravidian (Grimes 2000:452).

2.4 Mala Arayan

The term ‘Mala Arayan’ means ‘the lords of the hills’. Thurston (1909:452–455) describes the Mala Arayan as a hill tribe that was civilized and lived on the slopes of the high mountain ranges. Some of them are very rich. They are concentrated in the hilly tracts of Idukki and Kottayam districts. They are mainly in the Ilamdesham, Idukki, Azhutha, Adimali and Kattappana blocks in Idukki district. The community is a scheduled tribe in Kerala and is known as ‘Mala Arayan’ and ‘Malayarayar’, although these two names are synonymous. According to the 1991 census, the population of Mala Arayan in Idukki is 15,379. The 1999 ITDP report records that there are 4,432 Mala Arayan families in Idukki. Some Mala Arayan live in Tamil Nadu, where they have a population of 689 persons according to the 1991 census.

Mala Aryan used to speak a distinct dialect of their own which was unintelligible to other Malayalis in the past, but now they have adopted the regional Malayalam dialect of their locality (Menon

1996:198). Singh (1994:718) reported that Malayalam is their mother tongue and the same language is used for inter-group communication. They use the Malayalam script. One Mala Arayan person said that a few old people that live in interior locations might know their language. According to the 1981 census, their literacy rate was 77%, the highest among tribal populations in Kerala. Christian missionaries have started many schools in their area, which have provided good opportunities for quality education for many years. The 1981 census also reported that 53% of them are Hindus and 47% are Christians. The Christians are better off economically.

2.5 Urali

Upputhara, Kanchiyar, Vannappuram, Velliyamattom and Ayyappankovil panchayats. According to the 1999 ITDP report, there are 1,295 Urali families in Idukki district.

Non-tribal people as well as tribal people, like Muthuvan and Mannan, have repeatedly exploited the Urali people for years. Even today, outsiders are cheating them by giving less money for their agricultural goods and for the forest collections (Shashi 1994:161; 176). Each settlement consists of a

single clan with a kani (headman).

Their religion is a mixture of animism, totemism, magic, sorcery and ancestor worship. They believe in an immortal soul and in a supreme god, Padachathampuran, who is the creator of the universe and is formless and unknowable. They recently adopted Hindu gods, including Ayyappan and Kali. The 1981 census reported that 96% are Hindus and about 4% are Christians. They bury their dead. Betel leaves and rice are put in the mouth of the dead in order to appease the soul.

According to the 1991 census, the literacy rate among the Urali in Kerala was 56% (49% among males and 42% among females). Singh reports that Malayalam is their mother tongue and that they use the Malayalam script (1994:1,162). Selvaraj (1999:7) reports that Urali Bhasha of Kerala appears to be dying out because of language shift towards Malayalam.

2.6 Ulladan

The Ulladan are a scheduled tribe found mainly in Kottayam, Idukki and Pathanamthitta districts of Kerala. South of the river Pamba, they are also known as Katan, Kattalan and Kochuvelan. In Menon (1996:221), Luiz reported that the Ulladan that live in interior forests are known as Mala Ulladan, while those that live in the plains are known as Nadu Ulladan. The former are listed as a scheduled tribe, whereas the latter are listed as a scheduled caste. The 1991 census reports that the population of Ulladan is 14,846 in Kerala. According to the 1999 ITDP report, 1,020 Ulladan families live in Idukki and

Kattappana blocks of Idukki district.

Their tribal assembly consists of elderly members of the tribe. Their headman is called muppan.

Their religion was once purely animistic, but they have recently adopted the Hindu pantheon.

Thalaparamalaswami, the deity of the temple peak Thalaparamala, is the most worshipped supernatural being. They also adore the deities Kappiri, Theekutty and Chathan (Shashi 1994:12).

According to Singh (1994:1160) the mother tongue of Ulladan is Malayalam and Malayalam script is used by them. In Menon (1996:221), Nandi states the Ulladan speak Malayalam with some phonetic shifts, but they do not have a different dialect or distinguishable vocabularies. The people reported that they use only Malayalam. The literacy rate of Ulladan is 67% (70% among males and 64% among females), according to the 1991 census.

2.7 Mala Pulayan

Mala Pulayan is a scheduled tribe found mainly in the Devikulam taluk of Idukki district. They are included on the scheduled tribe list under the name Hill Pulaya. The population of the Mala Pulayan in Kerala, according to the 1991 census, is 2851 (1463 males and 1388 females) and their number in Idukki is 2106 (1079 males and 1027 females). The 1999 ITDP report claims that there are 860 Mala Pulayan families in Idukki district.

There are three divisions among them, the Kurumba Pulayan, Karavazhi Pulayan and Pambu Pulayan. The Kurumba Pulaya claim superiority because they do not eat the flesh of cattle. The Pambu Pulayan are considered to be the lowest, because they eat snakes. There is not much contact between these groups. Differences are observed in the social practices and religious beliefs among these subgroups.

The headman of the Kurumba Pulayan’s tribal council is known as the muppan. They bury their

dead in a sitting position. They worship Kali, Mariyamma, Kottaparamma, Chaplamma and Aragalinachi. Their main festivals are Pongal, Thai Pongal and Divali (Menon 1996:220).

same variety of Tamil language. In Menon (1996:218), Luiz reports that the Mala Pulayan speak a dialect of Tamil that is unintelligible to Tamil speakers, containing a large number of Malayalam words and phrases. They are involved in agriculture and also collect minor forest produce.

2.8 Paliyan

The name Paliyan has been spelled numerous ways, including Paliyar, Palliyar, Palliyan and Palleyan. Most of the Paliyan in Kerala live in Kumily, Vandanmedu and Chakkupallam panchayats of Pirmed tahsil of Idukki district. They also live in the neighbouring districts of Madurai and Ramanathapuram in Tamil Nadu and some parts of Karnataka state. It is believed that their original home was in Gudalur, Madurai district. According to the 1991 census their population in Tamil Nadu was 4,322, while in Kerala their population was 1,442. According to the 1999 ITDP report, there are 383 Paliyan families in Idukki district.

The Paliyan are primarily engaged in agriculture. They also collect forest produce, such as honey and dammar. They primarily marry members of their own people group. But intermarriage between Paliyan women and men from other groups is tolerated. Each settlement has a headman, known as the

kanikaran or vitu kani.

Paliyan religious beliefs are in a state of continuous change, including both traditional beliefs of their own and incorporating elements of Hinduism. Some believe that all souls go to heaven. Others believe in reincarnation. Still others believe in both reincarnation and the goal of reaching heaven. Different Paliyan people believe very different things without seeing a difference in their religion. Priests (pujaris) have a very influential role in Paliyan religious activities. The Paliyan worship various deities. Mariyamma is the most popular deity. Ancestral spirits are also worshipped. In Kerala, 80% of the Paliyan are Hindus and 20% are Christians. They bury their dead along with betel leaves, areca nuts, beedi and the personal belongings of the deceased (Menon 1996:301).

According to Singh (1994:963–965), in Tamil Nadu Paliyan speak Tamil and use the Tamil script for both inter-group and intra-group communication. In Kerala these people are bilingual, and use the regional state language Malayalam apart from their mother tongue, Tamil. Both Malayalam and Tamil scripts are used by them. Menon (1996:297), however, reports that the Paliyan in Kerala speak a

“corrupted” dialect of Tamil with many Malayalam words and usages. The language variety of Paliyan in Idukki is also called Paliya Bhasha by outsiders, especially Malayalis and Mannan people.

2.9 Mala Vedan

Mala Vedan people are found in both Kerala and Tamil Nadu. In Kerala, the Mala Vedan primarily live in Pathanamthitta, Trivandrum and Idukki districts. According to the 1991 census, the population of Mala Vedan in Kerala is 6,331 (1,235 of whom live in Idukki district). However, the 1999 ITDP report claims that there are only 35 Mala Vedan families in Idukki district. In Idukki, they live in Nedumkandam and Karimkunnam panchayats. They live together with people from various castes that have settled in their home area. The Mala Vedan are considered to be closely related to Ulladan and Mala Pandaram (Menon 1996:293).

In Tamil Nadu, they are identified as the Malai Vedan and are listed as a scheduled tribe. They are found mainly in Kanyakumari, Thirunelveli and Madurai districts. Their population in Tamil Nadu is 8,910. They speak a dialect of Malayalam (Vedan Bhasha). A few Mala Vedan people are literate in Tamil (Menon 1996:233).

The culture and speech forms of the people who are known by the names Veda/Malaveda/Vettuvar differ greatly. It has not been possible to ascertain whether or not all these people belong to the same tribe. It is possible that some of these groups have nothing in common except the name, as linguistic peculiarities of some speech forms suggest.

other hand, the data collected from seven Mala Veda settlements in Kollam district by Hyrunnisa Beegam (1991) shows that the speech of Mala Vedan people in this area has only marginal differences from Malayalam. She suggested that the speech and culture of the people known under the name Veda/Malaveda has to be intensely investigated due to their inter-group relation.

2.10 Mala Pandaram

The Mala Pandaram are also known as Hill Pandaram. The majority of them live in the forest tracts of Kollam and Pathanamthitta districts of Kerala and the rest live in Tamil Nadu. According to the 1991 census, the population of Mala Pandaram is 2839 in Kerala and 1930 in Tamil Nadu. The 1999 ITDP report claims that there are only six Mala Pandaram families in Idukki district. In Idukki they live in Pirmed and Peruvanthanam panchayats.

The people claim that they came to Kerala from Madurai and Thirunelveli districts of Tamil Nadu. They live in groups of three or four families for a while, and then eventually move on to another site. These sites are generally in the deep interior forests, away from other people. They have the institution of territorial chieftainship, and they remain some of the poorest people in Kerala. They are still semi-nomadic and in the hunting stage of economic development (Menon 1996:212).

They speak a dialect of Malayalam, locally termed Pandaram Bhasha. The Mala Pandaram converse with others in Malayalam and use Malayalam script (Singh 1994:733). In Menon (1996:212), Luiz reports that they “speak a poor dialect with many Tamil and Malayalam words and phrases.” Their religion is a mix of Hinduism and their traditional faith. According to the 1991 census, 37% of the Mala Pandaram are literate (44% of males and 31% of the females).

3 Dialect areas

One of the primary goals of this survey was to find out the degree of relationship that exists between Malayalam, Tamil and the speech varieties of Idukki district. Various tools were utilised to accomplish this objective, one of which was lexical comparison of wordlists. Another method of assessing

relationships among various speech varieties was dialect comprehension testing using Recorded Text Testing (RTT). Finally, formal questionnaires helped to make conclusions about these relationships. These methods and their findings will be discussed in detail in this chapter.

3.1 Lexical similarity

One method of assessing the relationship among speech varieties is to compare the degree of similarity in their vocabularies. This is referred to as lexical similarity. Speakers of varieties that have more terms in common (thus a higher percentage of lexical similarity) generally, though not always, understand one another better than do speakers of varieties that have fewer terms in common. Since only elicited words and simple verb constructions are analysed by this method, lexical similarity comparisons alone cannot indicate how well certain speech communities understand one another. It can, however, assist in obtaining a broad perspective of the relationships among speech varieties and give support for results using more sophisticated testing methods, such as comprehension studies.

3.1.1 Procedures

The tool used for determining lexical similarity in this survey was a 210-item wordlist, consisting of items of basic vocabulary, which has been standardised and contextualised for use in sociolinguistic surveys of this type in South Asia. The elicited words were transcribed using the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) shown in appendix A. To provide maximum reliability, some of the wordlists were checked with a second mother tongue speaker at the same site.

entire wordlist was evaluated, the total number of word pair similarities was tallied. This amount was then divided by the total number of items compared and multiplied by 100, giving what is called the lexical similarity percentage.

This process of evaluation was carried out according to standards set forth in Blair 1990:30–33 and facilitated using a computer program called WordSurv (Wimbish 1989). This program is designed to quickly perform the counting of word pair similarities and to calculate the lexical similarity percentage between each pair of wordlists. For a more complete description of counting procedures used in determining lexical similarity, refer to Appendix B.

3.1.2 Site selection

Twenty-one wordlists were compared in this lexical similarity study. Seventeen of the wordlists were collected during this survey in Muthuvan, Mannan, Paliyan and Mala Pulayan (Karavazhi Pulayan) villages. More focus was given to Muthuvan and Mannan speech varieties. Fifteen wordlists were collected from them, representing eight and seven locations respectively. It was reported that Paliyan and Mala Pulayan people speak a form of Tamil. One wordlist was collected from each of these varieties to verify the language situation. Two wordlists from Urali from a previous survey are also included in the lexical similarity comparison. Finally, one standard wordlist in Malayalam, the official language of the state covered in this survey, and one wordlist in Tamil, the neighbouring state language, were included in the lexical similarity comparison.

Eight wordlists were collected from Muthuvan. Five of these were from the Tamil Muthuvan variety and three were from the Malayalam Muthuvan variety. These sites were selected based on people group division as Tamil Muthuvan and Malayalam Muthuvan, geographical distribution (interior/exterior) and reported variation in dialect areas. Travel facility and permission to visit the area also influenced the site selection.

Mannan wordlists were collected from seven sites based on geographical distribution

(interior/exterior), reported dialect variation and cultural importance. In addition, importance also was given to visit major settlements of the area for wordlist collection.

Wordlists from Mala Vedan, Mala Arayan and Ulladan were not collected from the survey area since it is believed that the language varieties are no longer in use and have been replaced by Malayalam. Surveyors could not visit Mala Pandaram villages, as there was no information about any settlement that consists of more than three families in the district.

Map 2. Wordlist sites

© NLCI 2015

14

Table 5. Wordlist sites

Language/ Speech Variety

Village/ Settlement

Interior/

Exterior Block Tahsil District State Origin

Tamil Muthuvan Anachal/Itticity Exterior Adimali Devikulam Idukki Kerala This Survey Tamil Muthuvan Chempakathozhu Exterior Devikulam Devikulam Idukki Kerala This Survey Tamil Muthuvan Kavakudi Interior Devikulam Devikulam Idukki Kerala This Survey Tamil Muthuvan Kozhiyala Interior Devikulam Devikulam Idukki Kerala This Survey Tamil Muthuvan Valsapetti Interior Devikulam Devikulam Idukki Kerala This Survey Malayalam Muthuvan Kunchipara Interior Neriyamangalam Kothamangalam Ernakulam Kerala This Survey Malayalam Muthuvan Thalayirappan Exterior Adimali Devikulam Idukki Kerala This Survey Malayalam Muthuvan Kurathikudi Interior Adimali Devikulam Idukki Kerala This Survey

Mannan Vattamedu Exterior Idukki Udumpanchola Idukki Kerala This Survey

Mannan Veliyampara Interior Devikulam Devikulam Idukki Kerala This Survey

Mannan Kumily Exterior Azhutha Pirmed Idukki Kerala This Survey

Mannan Kovilmala Exterior Kattappana Udumpanchola Idukki Kerala This Survey

Mannan Kodakallu Interior Adimali Devikulam Idukki Kerala This Survey

Mannan Chinnapara Exterior Adimali Devikulam Idukki Kerala This Survey

Mannan Thinkalkadu Interior Nedumkandam Udumpanchola Idukki Kerala This Survey Urali Poovanthikudi Interior Kattappana Udumpanchola Idukki Kerala Betta Kurumba

Urali Vanchivayal Interior Pirmed Pirmed Idukki Kerala Betta Kurumba

Mala Pulayan Dendukombu Exterior Devikulam Devikulam Idukki Kerala This Survey

Paliyan Lebbakandam Exterior Azhutha Pirmed Idukki Kerala This Survey

Tamil Pudukottai and

Tuticorin

Tamil Nadu

Betta Kurumba

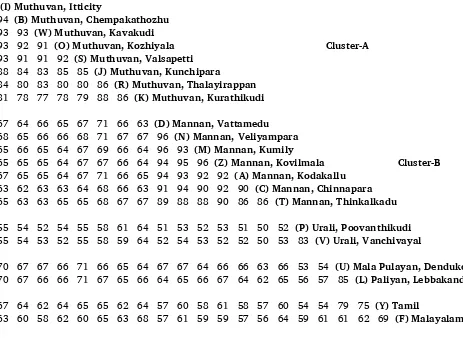

Table 6. Lexical similarity percentages

(I) Muthuvan, Itticity

94 (B) Muthuvan, Chempakathozhu

93 93 (W) Muthuvan, Kavakudi

93 92 91 (O) Muthuvan, Kozhiyala Cluster-A

93 91 91 92 (S) Muthuvan, Valsapetti

88 84 83 85 85 (J) Muthuvan, Kunchipara

84 80 83 80 80 86 (R) Muthuvan, Thalayirappan

81 78 77 78 79 88 86 (K) Muthuvan, Kurathikudi

67 64 66 65 67 71 66 63 (D) Mannan, Vattamedu

68 65 66 66 68 71 67 67 96 (N) Mannan, Veliyampara

65 66 65 64 67 69 66 64 96 93 (M) Mannan, Kumily

65 65 65 64 67 67 66 64 94 95 96 (Z) Mannan, Kovilmala Cluster-B

67 65 65 64 67 71 66 65 94 93 92 92 (A) Mannan, Kodakallu

63 62 63 63 64 68 66 63 91 94 90 92 90 (C) Mannan, Chinnapara

65 63 63 65 65 68 67 67 89 88 88 90 86 86 (T) Mannan, Thinkalkadu

55 54 52 54 55 58 61 64 51 53 52 53 51 50 52 (P) Urali, Poovanthikudi Cluster-C

55 54 53 52 55 58 59 64 52 54 53 52 52 50 53 83 (V) Urali, Vanchivayal

70 67 67 66 71 66 65 64 67 67 64 66 66 63 66 53 54 (U) Mala Pulayan, Dendukombu Cluster-D

70 67 66 66 71 67 65 66 64 65 66 67 64 62 65 56 57 85 (L) Paliyan, Lebbakandam

67 64 62 64 65 65 62 64 57 60 58 61 58 57 60 54 54 79 75 (Y) Tamil

16

3.1.3 Results and analysis

Table 6 shows the lexical similarity percentage of wordlists compared in this study. According to Blair (1990:24), it can typically be concluded that two-speech varieties that have less than 60% lexical similarity are different languages. For speech varieties that have greater than 60% lexical similarity, intelligibility testing should be done to determine their relationship.

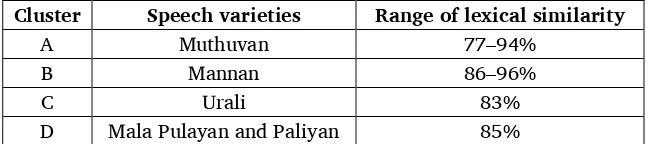

In the following analysis and discussion, wordlists are grouped in different clusters based on their highest lexical similarity. The study gives more emphasis to the lexical relationships within each tribal variety and with the state languages Malayalam and Tamil, rather than the relationships of different tribal groups’ varieties with each other. Table 7 shows the ranges of lexical similarity within each cluster.

Table 7. Ranges of lexical similarity within each cluster

Cluster Speech varieties Range of lexical similarity

A Muthuvan 77–94%

B Mannan 86–96%

C Urali 83%

D Mala Pulayan and Paliyan 85%

3.1.3.1 Cluster-A Muthuvan

There are two types of Muthuvan wordlists, namely Tamil Muthuvan and Malayalam Muthuvan. All of the wordlists from Muthuvan varieties show a range from 77% to 94% of lexical similarity with each other. Within Tamil Muthuvan varieties, the percentages vary from 91% to 94% and make it clear that they are varieties of the same speech form. Malayalam Muthuvan varieties share a range of 86% to 88% lexical similarity with each other. The distances between the Malayalam Muthuvan sites are great and there does not seem to be much contact between these villages. This may be the reason for the lower degree of lexical similarity among the wordlists from Malayalam Muthuvan (as opposed to Tamil Muthuvan) villages.

The Tamil Muthuvan wordlists share a range of 77% to 88% of lexical similarity with the Malayalam Muthuvan wordlists. This may be taken as a rough indication that they may be different speech varieties of the same language. Intelligibility testing may help clarify the situation. The wordlists collected from the Tamil Muthuvan variety show slightly greater similarity with Tamil (from 62% to 67%) than Malayalam (58% to 63%), the state language of Kerala. On the other hand, Malayalam Muthuvan varieties show about the same resemblance to Malayalam (63% to 68%) and Tamil (62% to 65%). The study shows that the influence of Malayalam and Tamil can be seen in Muthuvan varieties.

3.1.3.2 Cluster-B Mannan

The wordlists collected from Mannan varieties appear to be quite similar. The overall range of lexical similarity among these wordlists is from 86% to 96%. It can be observed that the wordlist from

Thinkalkadu shows comparatively less similarity with other Mannan varieties. The overall percentage of similarity among Mannan wordlists is higher when the Thinkalkadu wordlist is not included in the comparison (ranging from 90% to 96%). The Thinkalkadu wordlist shows slightly greater similarity with Malayalam (64%) than other Mannan wordlists do. The influence of Malayalam might explain this variation from other Mannan wordlists.

3.1.3.3 Cluster-C Urali

The Urali wordlists share 83% lexical similarity with each other. They share a range of 59% to 61% of similarity with Malayalam and 54% of similarity with Tamil and show that Urali is probably a different language from Malayalam and Tamil. Compared to other groups, Urali shows the most dissimilarity with the wordlists from other groups, as almost all percentages are in the 50s.

3.1.3.4 Cluster-D Mala Pulayan and Paliyan

The wordlists from Mala Pulayan and Paliyan shows more similarity to Tamil than other wordlists in this survey, with 79% and 75% respectively. This gives the impression that they are related varieties to Tamil. Although Mala Pulayan and Paliyan are different tribal communities, their wordlists show 85% lexical similarity to each other. Lexical comparison shows that the speech forms of Mala Pulayan and Paliyan are different from Malayalam (61% and 62% similarity respectively).

3.1.4 Conclusion

Based on lexical similarity, wordlists were grouped into different clusters, each of which represented the people groups studied. Within each cluster, lexical similarity was fairly high, indicating there was not much dialectal variation. Muthuvan showed more variation, particularly between Tamil Muthuvan and Malayalam Muthuvan. In general, the relationship between the tribal varieties and Malayalam and Tamil is such that they are on the border of being considered different languages. Mala Pulayan and Paliyan, however show a higher similarity with Tamil.

3.2 Intelligibility testing

Maggard (1998:14) has noted, “The definition of a language and a dialect is not always clear. The two terms have been used in many different ways. Common usage often applies the term language to the large, prestigious languages, which have an established written literature. The term dialect is then used for all other speech varieties. Some linguists use language to refer to speech varieties that share similar vocabularies, phonological and/or grammatical systems. Many times, the sense in which the two terms are used can vary.”

The researchers believe that an important factor in determining the distinction between a language and a dialect is how well speech communities can understand one another. Low intelligibility between two speech varieties, even if one has been classified as a dialect of the other, impedes the ability of one group to understand the other (Grimes 2000:vii). Thus comprehension testing, which allows a look into the approximate understanding of natural speech, was an important component of this research.

3.2.1 Procedures

Recorded Text Testing (RTT) is one tool that helps assess the degree to which speakers of related

linguistic varieties understand one another. A three to five minute natural, personal-experience narrative is recorded on cassette from a mother tongue speaker of the speech variety in question. It is then

evaluated with a group of mother tongue speakers from the same region by a procedure called Hometown Testing (HTT). This ensures that the story is representative of the speech variety in that area and is suitable to be used for testing in other sites.

Mother tongue speakers from other locations and differing speech varieties then listen to the recorded stories and are asked questions, interspersed in the story, to test their comprehension. Subjects are permitted to take tests of stories from other locations only if they perform well on a hometown test. This ensures that the test-taking procedure is understood.

comprehension of the text, and the average score of all subjects at a test point is indicative of the community’s intelligibility of the speech variety of the story’s origin. Included with the test point’s average score is a calculation for the variation between individual subjects’ scores, known as standard deviation, which helps in interpreting how representative those scores are.

After each story, subjects are asked questions such as how different they felt the speech was from their own and how much they could understand. These subjective post-RTT responses give an additional perspective for interpreting the objective test data. If a subject’s answers to these questions are

comparable with his or her score, it gives more certainty to the results. If, however, the post-RTT responses and test score show some dissimilarity, then this discrepancy can be investigated.

Refer to appendix C1 for a more complete description of Recorded Text Testing, as well as to Casad 1974. The stories and questions used in the testing also appear in appendix C2. In appendix C3, the demographic profiles of the subjects at each test site, the test scores and the post-HTT/RTT responses are given.

3.2.2 Site selection

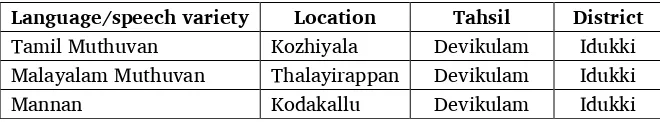

The primary objective of this study was to investigate the comprehension of speakers of Tamil Muthuvan and Malayalam Muthuvan of each other’s variety. There is only occasional contact between these two Muthuvan groups. In this study, two stories were developed (one in a Tamil Muthuvan settlement and the other in a Malayalam Muthuvan settlement) and tested. Another objective was to investigate the reported variation among Mannan speech varieties. For this purpose, one story was developed from a northern part of the Mannan-speaking area and tested in a southern part. Table 8 summarises the information about the stories and map 3 shows the test sites.

Table 8. Stories utilised in this project

Language/speech variety Location Tahsil District

Tamil Muthuvan Kozhiyala Devikulam Idukki

Malayalam Muthuvan Thalayirappan Devikulam Idukki

Map 3. RTT and LUAV sites.

© NLCI 2015

3.2.2.1 Kozhiyala (Tamil Muthuvan)

A Tamil Muthuvan story was recorded in Kozhiyala, a settlement of Devikulam Tahsil. Kozhiyala is an interior settlement that is situated in the forest. This would represent a central area of the Tamil Muthuvan variety. Idamalakudi is also a major settlement of Muthuvan and may be the most

geographically central place for Tamil Muthuvan. However, the researchers could not get permission to enter that area.

3.2.2.2 Thalayirappan (Malayalam Muthuvan)

Malayalam Muthuvan is spoken in Adimali block of Devikulam tahsil. Most of the settlements are in very interior locations. A Malayalam Muthuvan story was recorded in Thalayirappan settlement. The

settlement is six kilometres away from Adimali town and more easily accessible than other Malayalam Muthuvan settlements. This ideal location both represented the Malayalam Muthuvan variety and allowed the surveyors to have good contact with the people.

3.2.2.3 Kavakudi (Tamil Muthuvan)

Kavakudi is a Tamil Muthuvan settlement. It represents the north-eastern concentration of Tamil Muthuvan settlements. This site was selected for gauging comprehension of Tamil Muthuvan people of the Malayalam Muthuvan text from Thalayirappan. Another reason for selecting this site was to

investigate the acceptability of the language used in the Kozhiyala story that comes under the central area of Tamil Muthuvan variety.

3.2.2.4 Kodakallu (Mannan)

A Mannan story was collected from the settlement of Kodakallu in Devikulam tahsil to investigate whether there is any variation in the Mannan variety, as had been reported by this people group. It was believed that recording a story in one extreme end of the area and administering comprehension testing with it in another extreme end of the area would help clarify this situation. It was reported that people in Kodakallu speak a pure variety of the Mannan language, as compared with other Mannan settlements in that region. This is an interior village and has little direct contact with outsiders. The researchers had already made good contacts with the residents, which also supported the selection of this site for story collection.

3.2.2.5 Kumily (Mannan)

Kumily is located at an extreme southern end of the Mannan area. It was reported that their speech form has a unique style. Thus, it appeared to be a good location in which to check the acceptability and understanding of the speech form used in the Kodakallu story.

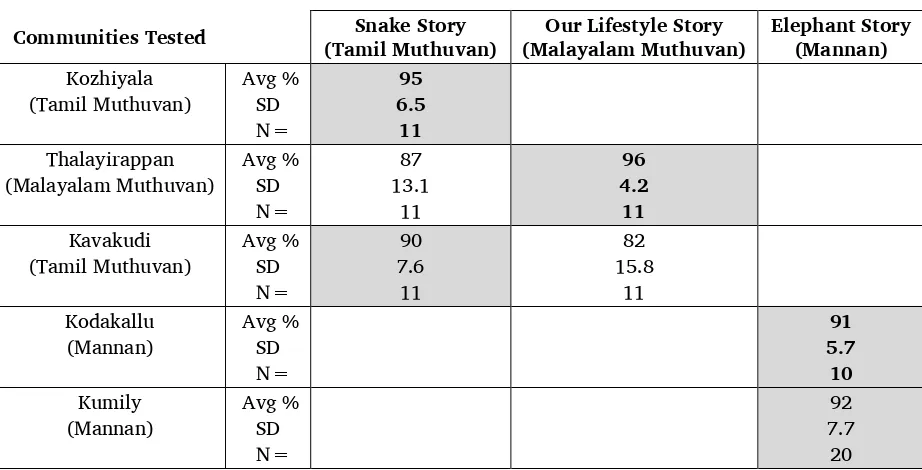

3.2.3 Intelligibility testing results and analysis

Table 9. Results of Recorded Text Testing

Stories Played

Communities Tested (Tamil Muthuvan) Snake Story (Malayalam Muthuvan) Our Lifestyle Story Elephant Story (Mannan)

Kozhiyala

In interpreting RTT results, three pieces of information are necessary. The first is average percentage (shown as Avg %), which is the mean or average of all the participants’ individual scores on a particular story at a particular test site. Also necessary is a measure of how much individuals’ scores varied from the community average, called standard deviation (shown as SD). The third important piece of information is the size of the sample, that is, the number of people that were tested at each site (shown as N=). In addition, to be truly representative, a sample should include people from significant demographic categories, such as both men and women, young and old, and educated and uneducated.

The relationship between test averages and their standard deviation has been summarised by Blair (1990:25) and can be seen in table 10.

Table 10. Relationship between test averages and standard deviation

Standard Deviation

Many people understand the story well, but some have difficulty.

Many people cannot understand the story, but a few are able to answer correctly.

Situation 4

Few people are able to understand the story.

that representatives of the test point dialect display adequate understanding of the variety represented by the recording. Conversely, RTT average scores below 60% are interpreted to indicate inadequate

comprehension. The following section highlights the results of comprehension testing, discussed in terms of the understanding of each story.

3.2.3.1 Tamil Muthuvan story

The test subjects of Kozhiyala scored well on their HTT with a low standard deviation, indicating that the story adequately represents their speech variety. Post-HTT responses indicate that the subjects believe that the language in the story is good, pure and represents their area.

The Tamil Muthuvan text from Kozhiyala was tested among Malayalam Muthuvan subjects at Thalayirappan for comprehension. The Thalayirappan subjects averaged 87% on the Kozhiyala story with a standard deviation of 13.1 (which is neither high nor low). It is thus believed that most Thalayirappan (Malayalam Muthuvan) subjects understand the Kozhiyala (Tamil Muthuvan) story, but some have difficulty.

Five out of the 11 Thalayirappan subjects mentioned that the Muthuvan language of the Kozhiyala text was mixed with Tamil. Three of the subjects stated that the language is Muthuvan, whereas two said that the language is not theirs. Most of the subjects mentioned the name of Tamil Muthuvan settlements as being the origin of the text. The subjects identified the language used in the story according to the language variety (Tamil mixing), the people (Tamil Muthuvan) and previous contact (having lived in that area). Four out of the five subjects that were asked the question “Was the text pure?” reported that “Yes, it is pure and good.” Most of the subjects mentioned that the language variety used in the text was somewhat different (either a little different or very different) from their local language variety. Seven out of 11 subjects whom the researchers asked this question reported that they fully understood the story, whereas three said they did not.

The comprehension testing among Malayalam Muthuvan subjects showed that many of them

understood the Tamil Muthuvan variety used in the story. It seems that the Malayalam Muthuvan subjects accepted the Tamil Muthuvan variety as a good variety. Most of the subjects reported that Tamil has influenced the language used in the story.

The Tamil Muthuvan subjects from Kavakudi scored an average of 90% with a standard deviation of 7.6 on Kozhiyala story, indicating that the subjects understood the story well. The language of the story was identified as their village variety or other (Tamil Muthuvan) village variety. The Post RTT responses reveal that the subjects understood the story fully and commented that the language was pure.

3.2.3.2 Malayalam Muthuvan story

Thalayirappan subjects scored an average of 96% on their HTT with a low standard deviation of 4.2, indicating a valid HTT and an understandable text. The text was understood and identified by all the subjects as being from their own variety. They also reported that the language of the story was pure and good.

The story from Thalayirappan was played for subjects in Kavakudi, a Tamil Muthuvan settlement. This was done in order to test comprehension and to learn about attitudes towards the Malayalam Muthuvan language variety. The subjects from Kavakudi scored an average of 82% with a standard deviation of 15.8. Though it can be interpreted that the Tamil Muthuvan subjects understood the story, the high standard deviation indicates that some of them had problems understanding the text.

3.2.3.3 Mannan story

The subjects for the Kodakallu HTT averaged a score of 91% with a standard deviation of 5.7 on the ‘elephant story’. The subjects identified the language of the story as being the same as they speak in their village and said that the speech variety is good and free from any mixing, except for one subject who reported that there is one Malayalam word in the text.

The 20 Mannan subjects in Kumily had an average of 92% on the story from Kodakallu, with a low standard deviation of 7.7. Various responses were given concerning the origin of the story. Four

mentioned that the story was from their settlement, whereas five realised that the story was not from their place. Three subjects said that it belonged to Kovilmala, the king’s place. Some subjects mentioned other places by name. Finally, another five subjects said that they did not know where the story was from. The responses, taken as a whole, give the impression that a majority of the Kumily subjects did not think that the story was from their own village.

Most of the subjects reported that, because of the slight difference in style, wording and tone from that of their own speech, the story was not from their own area. All but five of the subjects considered the speech good and pure. Two subjects said that it was not pure because they believe that Malayalam

language was mixed into the text. Half of the subjects stated that there is no difference between their speech and the speech of the story. And about half of the subjects reported that the ‘tone and wording’ of the story is a little different from how they speak. All of the subjects claimed to have fully understood the story. Some RTT subjects suggested that there may be minor variation among the speech varieties of Mannan in their style, wording and tone. Some influence of Malayalam vocabulary can be observed. Despite these observations, most subjects understood the story.

3.2.4 Conclusion

The comprehension testing among the speakers of Malayalam Muthuvan showed that many of them understood the Tamil Muthuvan variety. Many of them found no complexity in understanding this related speech variety. In general, there were no strong negative attitudes expressed by either group on the stories they listened to. There were comments from both groups about the amount of mixing of Tamil and Malayalam in the Tamil Muthuvan and Malayalam Muthuvan respectively. Because of this, many people identified the origin of the speech variety they listened to.

The intelligibility study among Mannan gives the impression that there is little language variation among Mannan speech forms. Moreover, some RTT subjects suggested that there may be minor variation among the speech varieties of Mannan in their style, wording and tone. Despite these observations, most subjects understood the story.

4 Language use, attitudes and vitality

A study of language use patterns attempts to describe which languages or speech varieties members of a community use in different social situations. These situations, called domains, are contexts in which the use of one language variety is considered more appropriate than another (Fasold 1984:183).

A study of language attitudes generally attempts to describe people’s feelings and preferences towards their own language and other speech varieties around them, and what value they place on those languages. Ultimately, these views, whether explicit or unexpressed, will influence the results of efforts towards literacy and the acceptability of literature development.

4.1 Procedures

Orally administered questionnaires were the primary method for assessing patterns of language use, attitudes and vitality in this survey. In addition to these questionnaires, observations and informal interviews were also made. The questionnaires were asked in Malayalam or the subject’s mother tongue (if they did not speak the state language). The Language Use, Attitudes and Vitality (LUAV) questionnaire can be found in Appendix D. Questionnaire responses were collected from six sites (shown in map 3), three each from Muthuvan and Mannan communities.

The following codes and abbreviations are used in this chapter: MT means ‘mother tongue’, LWC means ‘language of wider communication’ (Malayalam) and “Both” (when used in tables) means ‘mother tongue and language of wider communication (Malayalam)’.

Table 11 shows the questionnaire sites.

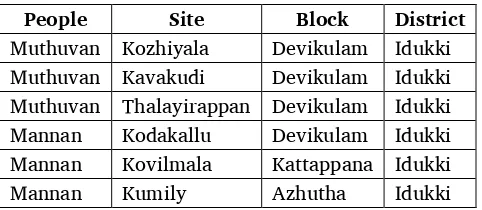

Table 11. Questionnaire sites

People Site Block District

Muthuvan Kozhiyala Devikulam Idukki

Muthuvan Kavakudi Devikulam Idukki

Muthuvan Thalayirappan Devikulam Idukki

Mannan Kodakallu Devikulam Idukki

Mannan Kovilmala Kattappana Idukki

Mannan Kumily Azhutha Idukki

4.2 Sampling distribution for questionnaire subjects

The researchers decided to find out if there is any variance between subjects that have completed different levels of formal education (uneducated, primary educated and fifth class and above). People from 16 to 35 years of age were considered as young and those above 35 were considered as old. The researchers tried to find subjects for each possible combination of these demographic factors, but in some instances this was not possible since Muthuvan ladies were reluctant to talk with young bachelors from outside their village. Tables 12 and 13 show the sampling of subjects for Muthuvan and Mannan respectively.

Table 12. Sampling of Muthuvan questionnaire subjects

Uneducated Primary educated Fifth class and above Total

Young Old Young Old Young Old

Male 4 7 5 4 5 3 28

Female 2 3 - - - - 5

Total 16 9 8 33

Table 13. Sampling of Mannan questionnaire subjects

Uneducated Primary educated Fifth class and above Total

Young Old Young Old Young Old

Male 4 2 6 4 5 3 24

Female 7 8 2 2 4 - 23

4.3 Muthuvan questionnaire results and analysis

4.3.1 Language use

The results of the language use questionnaire are summarised in table 14. All 33 subjects responded to each of the questions.

Table 14. Domains of Muthuvan language use

Qn Domains MT Both LWC LWC and

Tamil

Tamil Their

language

2a With parents 33 (100%) - - - - -

2b With their children 31 (94%) 2 (6%) - - - -

2c With village friends 27 (82%) 6 (18%) - - - -

2d With outsiders 1 (3%) - 18 (55%) 10 (32%) - 4 (12%)

2e Private prayer 27 (84%) 2a (6%) 1 (3%) - 2 (6%) -

3c By children while playing 31 (94%) 2 (6%) - - - -

aOne subject mentioned both MT and Tamil

At least 82% of Muthuvan subjects responded that they usually use their mother tongue in each domain they were asked about, with the exception of speaking with outsiders. It is unlikely that many outsiders know the Muthuvan language. Therefore, it is not surprising that the Muthuvan usually use Malayalam or Tamil with outsiders.

The overall results show that the mother tongue is often used among the Muthuvan people for communication amongst themselves and that they depend on either Malayalam or Tamil whenever they want to communicate with outsiders.

4.3.2 Language attitude

4.3.2.1 Attitude towards mother tongue compared with LWC

Qn.5. Which is your favourite language?

MT Malayalam Both MT and Tamil Tamil

17 (52%) 8 (24%) 5 (15%) 1 (3%) 2 (6%)

Half of the subjects expressed that they like their mother tongue better than any other language. Another 18% of the subjects stated that they equally like both their mother tongue and another language (either Malayalam or Tamil).

Qn.7. What language do your people (young people) like to speak when they go out?

MT Malayalam Both

17 (52%) 9 (27%) 7 (21%)

The objective of this question was to investigate perceptions regarding the attitudes of young people about their mother tongue. Half of the subjects believe that youth speak their mother tongue amongst themselves when they go out. Nine subjects (27%) reported the use of the LWC, five of whom are young subjects themselves. Seven other subjects (21%) reported that the young people speak both Muthuvan and Malayalam when they go outside of their settlement. Most of the 16 subjects that claimed that young people like to speak Malayalam or both Muthuvan and Malayalam, while outside their village, were young educated people.

Qn.8. Would your old people be happy if young people spoke Malayalam/Tamil in the home?

Yes No Indifferent answer Other responses

19 (58%) 7 (21%) 4 (12%) 3 (9%)

The objective of this question was to learn about perceptions of the attitudes of old people towards the use of Malayalam and Tamil. Many subjects reported that old people are not troubled by the use of Malayalam or Tamil in the home. Nearly half of the 17 older subjects reported that they are not bothered by the use of these LWCs in the home. The majority of the subjects, including older people, believe that older Muthuvan people have an open mind towards the use of LWCs in the home.

Qn.13. Do you feel that the Muthuvan language is as good as Malayalam/Tamil?

Yes No

31 (97%) 1 (3%)

This question was asked to compare the disposition of subjects towards their mother tongue with their feelings about LWCs. Nearly every subject said that they feel that their language is as good as the LWCs of their area.

4.3.2.2 Attitude for continuing their mother tongue

Qn.6. Do young people in your community feel good about your language?

Yes No Other responses

29 (88%) 1 (3%) 3 (9%)

The rationale for this question was to learn about the attitudes of the younger generation towards their mother tongue. A majority of the subjects (88%) reported that young people feel good about their language. This attitude may help ensure that their mother tongue will continue to be spoken in the coming years.

Qn.9. What language should a Muthuvan woman use with her young child?

MT Malayalam Both

31 (94%) 1 (3%) 1 (3%)

This question was asked to see if Muthuvan mothers prefer to pass on their language to the next generation. Almost all subjects expressed that they believe Muthuvan women should speak to their young children in her mother tongue. The responses clearly indicate that the Muthuvan people have the desire to pass their language on to succeeding generations.

Qn.10. Would you be happy if your child only spoke Malayalam/Tamil?

Yes No Happy and unhappy Neutral feelings Other responses

12 (37%) 11 (33%) 2 (6%) 6 (18%) 2 (6%)