STRENGTHENING BUSINESS

COMPETITIVENESS FOR

A PROSPEROUS INDONESIA

Findings from APINDO's 2014 Survey on

Business Competitiveness in Indonesia

Vol. P.001/DPN-EUKAJ-III/2014

Pelindung:

Hariyadi B.S. Sukamdani

Pembina:

Chris Kanter, Suryadi Sasmita,

Shinta Widjaja Kamdani, Sanny Iskandar

Pemimpin Redaksi:

P. Agung Pambudhi

Tim Penyusun:

Diana M. Savitri, Riandy Laksono, Maya Safira M. Rizqy Anandhika, Sehat Dinati Simamora I.B.P. Angga Antagia, Jefri Butarbutar Adrinaldi Wahyu Handoko

Penyunting:

Septiyan Listiya Eka R.

Dewan Redaksi

Copyright (c) APINDO

Strengthening Business Competitiveness for a Prosperous Indonesia

Published in December 2014

APINDO-EU ACTIVE Project Team Members:

Maya Safira (Project Manager) Riandy Laksono (Lead Economist)

Muhammad Rizqy Anandhika (Economist) Sehat Dinati Simamora (Junior Economist) Nuning Rahayu (Project Assistant)

The content of APINDO-EU ACTIVE working papers is the sole responsibility of the author(s) and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of Indonesia Employers Association (APINDO) or its partner instututions. APINDO-EU ACTIVE working papers are preliminary documents posted on the APUNDO website (www. apindo.or.id) and widely circulated to stimulate discussion and critical comment.

Disclaimer

APINDO – EU ACTIVE working papers are issued in joint cooperation between Indonesia Employer Association (APINDO) and Advancing Indonesia's Civil Society in Trade and Investment (ACTIVE), a project co-funded by the European Union. ACTIVE project aims to strengthen APINDO's policy making advocacy capabilities in preparing the business environment and to empower national competitiveness in facing global integration.

For more information, please contact ACTIVE Team at

active@apindo.or.id or visit www.apindo.or.id

he global competitiveness map is changing right now, as China becomes a more expensive production location following its rapid wage rise. There is an opportunity for Indonesia to regain competitiveness in manufacturing exports, thus boosting up Indonesia's welfare. To tap optimally into this opportunity, Indonesia needs to set the right policies, especially by having a solid productivity-driven growth strategy. The central piece on the productivity-driven growth is that Indonesia should revitalize its manufacturing export and Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) performance, especially FDI that focus more on export market, instead of only domestic market. To do so, it requires signi icant improvement in the business competitiveness, so that export-oriented irms are attracted to invest and produce in Indonesia.

APINDO's Survey on Business Competitiveness aims to map the ability of Indonesian irms to compete in global market by identifying many recognizable business obstacles. This study tries to complement other existing index and ranking available publicly with a closer look on what matter the most for Indonesian businesses, especially the aspects central to business competitiveness such as logistics, infrastructure, and employment regulation in Indonesia. This study also provides practical recommendation to move Indonesian economy forwards, strengthen business competitiveness, and stimulate con idence among Indonesian businesses to better compete in the international market. In long term, this study is expected to become a systematic mechanism to monitor dynamic and development of competitiveness in Indonesia.

Overall, we convey our appreciation to APINDO – EU ACTIVE Project Team who has successfully delivered this policy study, especially to Riandy Laksono and Maya Sa ira as the authors. We hope our study can contribute a signi icant input on improving further business competitiveness and investment climate for a prosperous Indonesia.

T

Hariyadi B.S. Sukamdani

General Chairman

The Employer's Association of Indonesia (APINDO)

Chris Kanter

Acknowledgement...ii

Foreword...iii

Table of Contents...iv

A. A One Time Window of Opportunity...2

B. About the APINDO's Business Competitiveness Survey...5

C. Indonesia's Business Environment 2014...6

C. 1. Major Roadblock to Business Competitiveness: an Insight for Policy Prioritization...6

C. 2. Labor Market Condition: Rigid Regulation, Low Compliance, and Shortage of Skilled-Workers...11

C. 3. Infrastructure and Logistics...17

D. Business con idence and moving forward beyond 201.………….………...22

D. 1. Indonesian businesses are ready to face tighter competition in AEC 2015………...22

D. 2. Perception on the effect to Indonesian business sector if FTA between Indonesia and European Union is being implemented………...…...23

D. 3. Business Prospect: Politics and Global Situation……...………....24

D. 4. Policy Recommendation on Strengthening Business Competitivene...27

References...31

Appendices...32

STRENGTHENING BUSINESS COMPETITIVENESS

FOR A PROSPEROUS INDONESIA

Findings from APINDO's 2014 Survey on Business Competitiveness in Indonesia

Key Findings:

Ø The large gap on income growth path across countries is best explained by the differences in

their labor productivity level. As Indonesia aspires to be one of the high-income countries in the near future, it needs to develop productivity-driven growth strategy, with robust business competitiveness as its core element.

Ø Business licensing, customs procedures, access to inance, logistics infrastructure, and

availability of skilled workers are among the top 5 major impediments to business competitiveness. There is the case that SMEs and large enterprises tend to perceive a different degree of severity for each problem.

Ø Indonesia's current position of competitiveness is perceived lower than that of other

developing Asia countries, however business sees a quite positive trajectory in place.

Ø Logistics infrastructure and legal certainty are the competitiveness elements that have the

poorest performance among others, while political stability and macroeconomic policy are the best performer.

Ø Labor market condition in Indonesia is among the most rigid in the region where regulations

concerning the creation and termination of employment relationships are relatively costly.

Ø Businesses respond the minimum wage increase mostly through: not recruiting more new

workers for a certain period, passing the cost increase onto the consumers, and investing more on the technology.

Ø There are evidences of shortage of skilled-labors in Indonesia both at sectoral level as well as

at national level.

Ø The problem in logistics infrastructure in Indonesia does not only lie in the lack of physical

infrastructure, but more importantly also the institutional aspect.

Ø There needs to develop reliable electricity infrastructure, especially at the regional level, to

further boost up the region's development.

Ø Despite low level of business competitiveness and all the impediments facing the business

A. A One Time Window of

Opportunity

ndonesia aspires to close the gap with high-income countries, boost prosperity, and avoid the

middle-income trap.

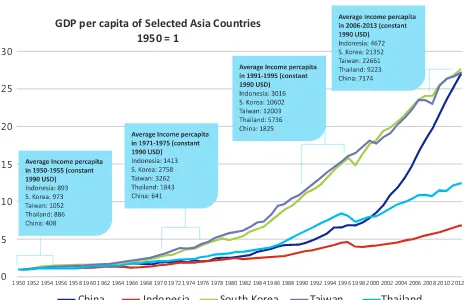

These are ambitious but achievable goals, especially if we put historical perspective into the context. Indonesia started at the comparable income level with Thailand, Taiwan and South Korea back at the 1950; China was even way poorer than Indonesia at that time¹. What happen is that Taiwan and South Korea–focusing on massive investment in human capital, manufacturing and technology–experienced a very rapid income growth since the second half of 1960's thus leaving Indonesia well behind while they become solid high-income countries in 1990's.

This is also true for Thailand in late 80's where it outperformed Indonesia and positioned well above Indonesia in the 90's thus better af irming its position as an upper-middle income countries and further setting the right track on becoming high income countries in the future. China, though started signi icantly poorer than Indonesia, were able to grow very robust over time and inally managed to record double digit income growth during the 2000's making it leapfrogged Indonesia in term of GDP per capita; thanks for its heavy investment in infrastructure and high productivity in low-skilled manufacturing sectors.

Indonesia, on the other hand, only recorded modest income growth and never touched the rapid growth rate experienced by those countries that

overtook its position (see Figure 1)

The period of 2000's is a very crucial

period. This is the period where China's

income inally leapfrogged Indonesia's. It should be of note that before Asian Financial Crisis (AFC), Indonesia's income was still well above China and it had arguably set the right track to becoming upper-middle and even high-income countries by having a robust manufacturing base. However, after recovering from the AFC Indonesia was kind of losing grasp to make it back on track. At a relatively stable period, 2003-2011, Indonesia was very much into commodity export, driven by global commodity boom during that period. As opposed to strong manufacturing production and export in China, Indonesia's manufacturing competitiveness in 2000's was in the decline, moreover considering the strategy of Bank of Indonesia to keep Rupiah strong at that time.

I

FIGURE 1.Income Growth Path in Selected Asian Countries, 1950-2013

Note: The igure on GDP per capita uses constant 1990 USD value converted using Geary Khamis PPPs. The growth path is indexed using 1950's value as a benchmark

Source: The Conference Board, Total Economy Database (January 2014)

Even worse, the policy makers tend to marginalize investment in infrastructure and connectivity, which is very essential for manufacturing competitiveness, and prefer to spur money on highly inef icient petrol subsidy instead. As a result, Indonesia becomes too dependent on oil import, external balance tended to be more vulnerable to shock, and investors begin to l o s e c o n i d e n c e w i t h I n d o n e s i a' s fundamental. What happen in the following years was that investors tended to opt out, making Indonesia's Rupiah depreciated signi icantly, current account de icit widen at a rate never seen before in the last decade, and eventually all contractionary policy

necessary to tame those negative trend resulted to a slower economic growth rate.

In this decade, Indonesia lost the m o m e n t u m o f r a p i d g l o b a l manufacturing growth, while China took the advantage and dominate global manufacturing production, especially the

low-skilled manufactured goods. This is

why China could boost its income so rapidly, while Indonesia's stayed modest at the 2000's.

The diverging income growth path between those countries is best explained by two factors: the difference in their labor productivity level and share of the 1950 1952 1954 1956 1958 1960 1962 1964 1966 1968 1970 1972 1974 1976 1978 1980 1982 1984 1986 1988 1990 1992 1994 1996 1998 2000 2002 2004 2006 2008 2010 2012

30

25

20

15

10

5

0

China Indonesia South Korea Taiwan Thailand

Based on GDP per capita decomposition as follows: GDP/population = GDP/workers * workers/population. The irst right-hand side term refers to the aggregate labor productivity, while the second refers to the proportion of total population employed

2

population employed². Latest research show that 92 percent of the differences in GDP per capita across countries are explained by differences in labor productivity (IMF 2013).

Thereby, for Indonesia to have a rapid income growth in order to close the gap with other high-income countries and avoid middle-income trap, it needs to develop a solid productivity-driven

growth strategy. The central piece on the

productivity-driven growth is that Indonesia should revitalize its manufacturing export and Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) performance, especially FDI that focus more on export market, instead of only domestic market. To do so, it requires signi icant improvement in the business competitiveness, so that export-oriented irms are attracted to invest and produce in Indonesia. Even more important, Indonesia needs a much stronger business competitiveness environment than its competitors, especially other developing Asia countries.

Indonesia can't afford to stay too long as a

lower-middle income country. It needs to

raise the income of its people and especially of the poorer 40% of the population. It has to also ensure more and better employment creation to feed the young-new workforce entrants. Indonesia only has this one time

window of opportunity. Demographic

bonus, the era where we can easily ind abundant source of productive workers, will b e s t o p p e d b y 2 0 3 0. T h e g l o b a l competitiveness map is changing right now, as China becomes a more expensive production location following its rapid wage rise. It presents Indonesia with a potential to regain competitiveness in labor-intensive manufacturing exports. If Indonesia manages to make the most of this

opportunity by having right policies, Indonesia is predicted to be able to capture 10% of China's 2012 market for labor intensive manufactures (Papanek, et.al. 2014). In reverse, if Indonesia fails, it would be there for other competitors, like Vietnam, Bangladesh, and other less-developed countries, to tap into this golden opportunity and using it to leapfrog Indonesia sometime in the near future. As depressing as it sounds, Indonesia then might well get trapped in the lower-middle income status for quite a time.

Given limited resources to deal with these global challenges and opportunities, it is indeed a tough task for policymakers to make the right decision on how to s t r e n g t h e n I n d o n e s i a' s b u s i n e s s competitiveness in order to boost country's productivity. APINDO's Survey on Business Competitiveness seeks to dig deeper on the obstacles that have long stalled business advancement in Indonesia so that policymakers and businesses can have a more complete and deeper view regarding what aspects that should be improved to better compete in

a more globalized world economy. This

B. About the APINDO's

Business Competitiveness

Survey

The APINDO's business competitiveness survey is conducted in two simultaneously ways: face-to-face interview and online survey. The survey managed to get 106 respondents that are located in 4 major business districts in Indonesia, namely: Medan, Greater Jakarta (Jabodetabek), Semarang, and Surabaya. Most of the respondents are the key industry players that operate almost in all regions in Indonesia, from Sumatera to Papua. Therefore, this survey is arguably representative enough to sort of peeling out major problems impeding business growth and to having overall view about the recent business competitiveness in relative with other major competitors of Indonesia, especially in major developing Asia countries.

Apart from the general questions asking about major impediments to business, one of the major features of this survey is that it asked the respondents to score out Indonesia's competitiveness level as compared to other developing Asia countries as our proxy of Indonesia's major competitors. The argument is that competitiveness should not be measured in an absolute-independent term, but it should also be measured in a relative to other countries: how good Indonesia is comparing to other comparable countries. To get a sense of how to improving business competitiveness and invite export-oriented irm to invest and produce in Indonesia, we have to know deeper about Indonesia's relative strengths and w e a k n e s s e s a s c o m p a r e d t o o t h e r competitors, so that we can have a more solid evidence on what should be in the policy prioritization for improvement.

Other major feature of this survey is that it contains special focus to employment policy, logistics, and infrastructure situation in Indonesia, and to some extent also a closer look at the regional level. The argument of having these special focuses is that these are the elements that score rather poorly in s eve ra l gl o b a l s u r vey, e . g . G l o b a l Competitiveness Index (GCI), Enabling Trade Index, Doing Business, etc. For instance, Indonesia's labor market ef iciency ranks very poorly in the GCI

2014-th

2015 that is 110 out of 144 countries (WEF 2014). Indonesia, though improving, still ranks below Malaysia and Thailand in Ease of Doing Business Index, in term of “trading across border”, which implies the need for further boosting up trade logistics and infrastructure development in Indonesia. This study wants to dig and evaluate these problems deeper by inding more profound evidence and putting more local context to it, where possible.

C. I n d o n e s i a 's B u s i n e s s

Environment 2014

C.1. Major Roadblock to Business

Competitiveness: an Insight

for Policy Prioritization

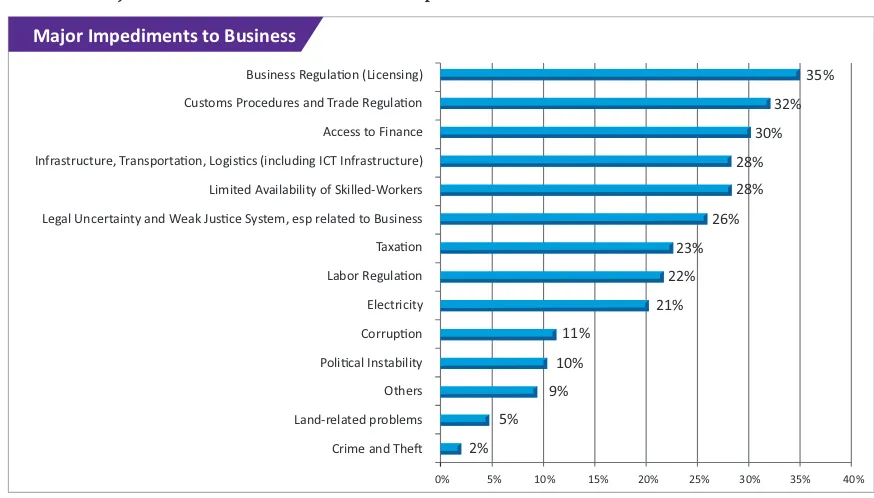

There are 5 major impediments that are perceived by Indonesia's private sectors as having the highest degree of barriers for their businesses (see Figure 2), namely Business licensing (35% of respondents); customs procedures and trade regulation ( 3 2 % ) ; a c c e s s t o i n a n c e ( 3 0 % ) ; infrastructure, transportation and logistics (28%); as well as limited availability of skilled-workers (28%). This inding re lects largely the situation business sector have to deal with in a routine basis. In Indonesia, u n l e s s we u s e a s e r v i c e f ro m t h e agent/brokerage, it will take years in order to get a complete-set of license to be legally registered as a business entity in the speci ic sectors. It sometime will take weeks for the importers to have their products being loaded from the ship and have them stored in their warehouse, not solely because of congested port and inef icient customs procedures, but also stringent trade rules. It is also 2 until 3 times much cheaper for fruit distributors in Jakarta to import orange fruit from China than have it delivered from Medan, because of highly inef icient domestic logistics, infrastructure, and transportation system. Entrepreneurs in Indonesia are also facing 2 or 3 times higher price of investment credit than in other major developing countries in Asia, like China, Malaysia, and Thailand. Furthermore, Indonesia's employers have to pay higher mandated wages for a much lower human capital than that of Thailand, Malaysia, and China.

Respondents, in general, also indicate the problems in the taxation, legal certainty, corruption, electricity, and land-related problem to have negative impact for their businesses, though not as severe as the previously mentioned top 5 major impediments. All of this means high cost and serves as major roadblock for

business competitiveness.

Outside the option that has been provided in the questionnaire, respondents also highlight a few of other signi icant impediments to business growth, namely currency and raw material. There are 2 major issues regarding the currency and why business might be negatively affected by that. Firstly, at pre-2011, before the current account de icit took place in Indonesia's economy and while the commodity was still booming, the Central Bank of Indonesia (Bank Indonesia) had preferred to keep the rupiah strong. It might be good news for the importers and the consumers, but it certainly hurts the competitiveness of export-oriented manufacturing irms, especially the labor-intensive industry.

Papanek et.al. (2014) found that from 2008 to 2011, workers “real wage” (purchasing power) stayed essentially the same, but the cost of labor for exporters increased 27% because of the exchange rate appreciation over that time. They said that Indonesia's exchange rate management system at that time seemed to ignore its impact to domestic production, employment, and certainly the industrial development.

and policy breakthrough from the government in order to improve the economic fundamental, Rupiah is often going up and down in a high variability re lecting largely of how con idence the investors are with the reform and breakthrough package being launched by the government. Therefore, in this period, the stability of rupiah has become a very big issue for businesses, especially the ones that linked intensively with international trade and investment activity.

The main message here is that keeping the currency low to support manufacturing competitiveness is essential to be done, however it should not interfere with the need to have a signi icant degree of

stability. That is to say, the central bank of

Indonesia (Bank Indonesia) should not let Rupiah moving down very aggressively and in a high variability in the name of boosting manufacturing export competitiveness, because it will create instability and u n p re d i c t a b i l i t y e nv i ro n m e n t fo r b u s i n e s s e s , t h u s h a r m i n g t h e i r

competitiveness instead.

[image:11.623.90.527.476.725.2]Another speci ic impediment raised up by the respondents is the availability of raw and supporting materials for the industry. Usually, irms tend to import quality materials from abroad as a part of their production process. The drawback of doing this is that it is quite expensive; combined with unstable currency, it would inancially harm the companies. However, reliable suppliers of raw materials–in term of production scale and quality–are not yet available at the domestic level, so that switching to source input domestically is not a viable option at the moment. There is a gap between the capacity of local supporting industry (such as raw material suppliers) and the potential demand of manufacturing sector, especially, the light industries, such as textile and apparels. Sourcing the raw materials domestically would be of their signi icant bene it, as they will be able to gain more given the narrow margin in the lower-value added market.

FIGURE 2.Major Obstacles to Business Competitiveness

Note: the igure is in the percentage to total respondents

Source: Author's calculation based on APINDO's survey on business competitiveness (2014)

Major Impediments to Business

Business Regula on (Licensing) Customs Procedures and Trade Regula on Access to Finance Infrastructure, Transporta on, Logis cs (including ICT Infrastructure) Limited Availability of Skilled-Workers Legal Uncertainty and Weak Jus ce System, esp related to Business Taxa on Labor Regula on Electricity Corrup on Poli cal Instability Others Land-related problems Crime and The

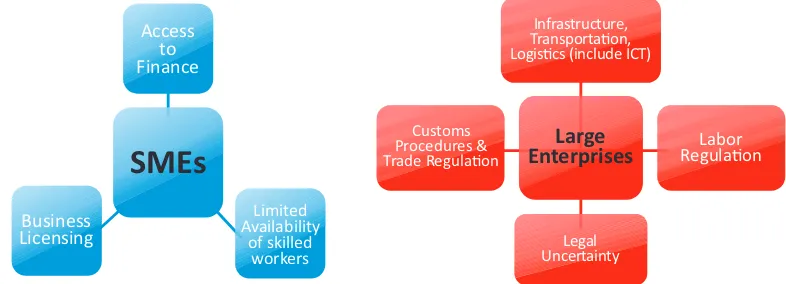

We also found that as the irms' scale varies, they tend to perceive a different degree of severity for each problem

(Figure 3). For small enterprises

(employing less than 10 workers), it is the access to inance (said more than half of respondents), then followed by business licensing (50%) and limited availability of skilled workers (43%) that are perceived to be the most hampering problems. It still holds true for the case of medium enterprises (employing 50 to 100 workers), except now they perceive a more balance degree on the severity of those problems.³ The condition is quite different for the large enterprises (employing more than 100 workers), whereby labor regulation, customs procedures and trade regulation, infrastructure, transportation, and logistics, as well as legal uncertainty are perceived as the major impediments for their business.

Small-and-Medium Enterprises (SMEs) are struggling to expand their business scale/activity, that's why the most important aspects for them is how to get enough inancial support and quality workers to help grow their companies, as well as how

the regulation can be ine-tuned so that they won't get so burdened by the signi icant compliance cost usually created by excessive business regulation/licensing. On the other hand, larger enterprises concern more about customs, trade regulation, trade infrastructure and logistics as they are dealing with trading activities more intensively than SMEs. Labor regulation is also a more pressing issue for them, as they have to deal with labor union, high uncertainty in minimum wage setting process, as well as high severance pay. The main reason why these problems are more prevalent in large enterprises than in SMEs might be that pressure for compliance to labor regulation is higher in large enterprises than in SMEs. Although SMEs will expectedly be the one that is hurt the most by high minimum wage and severance pay, they can still go “underwater” (informal) without having signi icant pressure for compliance because labor union is not that powerful in SMEs. Legal uncertainty is perceivably a more concerning problems for large enterprise than for SMEs because large enterprises often have to secure million or even billion dollar business transaction, sometimes with foreign partners, so that they become more demanding for improvement in legal system than SMEs do.

[image:12.623.117.510.517.659.2]3

FIGURE 3. Major Impediments to Businesses: SMEs Vs. Large Enterprises

Notes: SMEs employ less than 100 workers; Large Enterprises employ more than 100 workers Source: Author's calculation based on APINDO's survey on business competitiveness (2014)

Around 35% of respondents in medium enterprises category chooses access to inance, business licensing, and limited availability of skilled workers as their top 3 major impediments for their businesses.

Access to Finance

SMEs

Business Licensing Limited Availability of skilled workers Large Enterprises Customs Procedures &Trade Regula on Regula onLabor Infrastructure,

Transporta on, Logis cs (include ICT)

This survey was asking the respondents on how they perceived about the position and trajectory of business competitiveness in Indonesia in general as compared to other developing countries in Asia. The tendency of responses is that in general the current position of business competitiveness in Indonesia is considered worse as compared to other developing countries

in Asia (majority of 49.52% respondents

said so), however they felt that at least it

keeps improving over time (61% of

respondents). It means that though the current position of competitiveness is still lacking to other developing Asia countries, there's still positive trajectory in place.

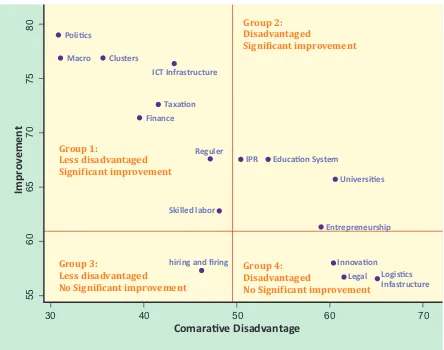

This study disaggregates competitiveness indicators into 16 elements (see Appendix A). Most respondents perceived that all the 16 elements are considered as Indonesia's structural weaknesses, meaning that all the 16 competitiveness elements are perceived to be worse than those of other

developing countries in Asia. However at

the same time, most respondents also felt that the quality of all the 16 competitiveness elements are keeping the pace to those of other developing Asian countries, if not pulling ahead.

Figure 4 summarizes the assessments on t h o s e 1 6 e l e m e n t s o f b u s i n e s s competitiveness. The horizontal axis captures the current position of business competitiveness in Indonesia for each element. It records the portion (%) of respondents perceiving each element in Indonesia to be worse than other developing countries in Asia. The motivation of why the data on the horizontal axis is presented in this way is that we want to highlight which competitiveness' elements are perceived to be the worst among others, so that it might bene it policy makers in term of policy prioritization given limited

resources yet unlimited, or very high,

expectation from the business sector. The

vertical axis, on the other hand, provides an insight about the competitiveness trajectory in Indonesia, by measuring the extent to which the respondents felt that the business competitiveness in Indonesia is improving, in the sense that it is keeping the pace, if not pulling ahead of other developing Asian countries over time.

At one edge, there are competitiveness' elements that experience signi icant improvement and position well above others, included here are political stability, macroeconomic policy, availability of clusters, ICT infrastructure, taxation, inance, and business regulation (group 1 as depicted in Figure 4). At the other edge, t h e r e a r e a l s o t h e e l e m e n t s o f competitiveness that have both stagnant improvement and poor position in the competitiveness level, such as logistics infrastructure, innovation infrastructure, and legal certainty and enforcement (group 4). In between, there are improving elements, yet still positioned poorly in term of their competitiveness level, such as IPR system, the quality of education system, linkage between universities and private s e c t o r s , a s w e l l a s s u p p o r t f o r entrepreneurship (group 2). The practice of hiring and iring of the workers in Indonesia, albeit ranked very poorly in the GCI 2014-2015 data, is still perceived as less disadvantaged elements compared to other components, with a stagnant improvement (group 3).

In term of policy sequencing (given limited government's resources), it might be best t o i r s t l y p r i o r i t i z e o n t h e competitiveness' elements which Indonesia's lacking the most, namely the elements that fall under the group 4 and

competitiveness trajectory of group 4 is less satisfying than group 2, the government might want to prioritize group 4 irst, then moving on to group 2. After nurturing those disadvantaged elements, it is equally important for the government to paying attention also in improving the lexibility of hiring and iring of the workers (group 3), while also keeping the relatively stronger elements under the group 1 from falling behind, and making their competitiveness level even better compared to other developing countries in Asia.

Note: the red line depicts the general situation on Indonesia's business competitiveness, while the magenta dot captures the competitiveness condition (horizontal) and trajectory (vertical) for each element de ined in the survey

[image:14.623.97.541.305.655.2]Source: Author's calculation based on APINDO's survey on business competitiveness (2014)

FIGURE 4. Assessments on the Elements of Business Competitiveness

Group 1:

Less disadvantaged Signi icant improvement

Group 2: Disadvantaged

Signi icant improvement

Group 3:

Less disadvantaged

No Signi icant improvement

Group 4: Disadvantaged

No Signi icant improvement Poli cs

Macro Clusters

ICT Infrastructure

Taxa on Finance

Reguler

IPR Educa on System

Universi es

Skilled labor

Entrepreneurship

Innova on

Legal Logis cs Infastructure hiring and firing

30 40 50 60 70

Comara ve Disadvantage

55

60

65

70

75

80

Impr

ov

emen

C.2. Labor Market Condition:

R i g i d R e g u l a t i o n , L o w

Compliance, and Shortage of

Skilled-Workers

Labor market condition in Indonesia is among the most rigid in the region where regulations concerning the creation and t e r m i n a t i o n o f e m p l o y m e n t

relationships are relatively costly. This

study reveals that the majority of 60.4% respondents agreed that the current

[image:15.623.152.484.281.519.2]regulatory environment surrounding labor market in Indonesia is detrimental for their business growth and competitiveness. The agreement rate is even higher for the large enterprises (74.4%) as compared to the SMEs (53%). It relates to the previous inding that the larger enterprises see labor regulation as a more concerning problems than SMEs do, noting that pressure from trade union and for compliance are higher in large enterprises than in SMEs.

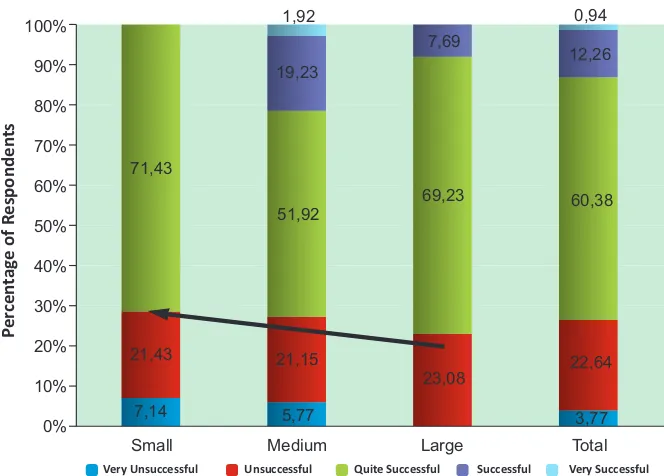

FIGURE 5. How Successful Are Indonesia's Business in Competing with other Comparable Competitors in other Developing Asia Countries?

Source: Author's calculation based on APINDO's survey on business competitiveness (2014)

All in all, apart from the fact that all the impediments being identi ied are prevalent and deteriorating for the businesses, there is still a modest optimism among the

private sectors showing that they feel quite

successful in competing with the rivals from other developing countries in Asia. Around 73% of respondents said that they either feel quite successful, successful, or very s u c c e s s f u l i n c o m p e t i n g w i t h t h e

comparable irms in other developing Asia countries. However it must be of note that as the irms' scale get smaller, they tend to feel more unsuccessful in competing with other comparable irms from developing

Asia countries (see Figure 5). Small and

medium enterprises (SMEs) ind it harder to successfully competing with other irms from developing Asia countries than large enterprises do.

Very Unsuccessful Unsuccessful Quite Successful Successful Very Successful 7,14 21,43 71,43 5,77 21,15 51,92 19,23 1,92 7,69 69,23 23,08 3,77 22,64 60,38 12,26 0,94 100% 90% 80% 70% 60% 50% 40% 30% 20% 10% 0% Per cen tag

e of R

esponden

ts

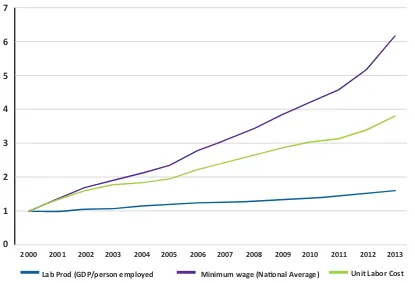

At the central of rigid labor market regulation in Indonesia is minimum wage that is ever increasing and highly uncertain in term of its determination process as well as highly binding and expensive mandated severance payment. Minimum wage in Indonesia is pretty expensive by developing-manufacturing countries

standards. It increases in a fast rate and is

not really linked much to the productivity improvement of the businesses. From 2000 to 2013, minimum wage has increased more

than six fold, while the labor productivity has barely been doubled. This, then, leads to a

sharp increase in the cost of labor input

required to produce one unit of output (unit labor cost), which rises 11.1 % annually or have almost been quadrupled in the last 13 years (see Figure 6). If the labor cost continues to increase so fast that productivity cannot even keeping the pace with it, Indonesia will soon risk l o s i n g i t s c o m p e t i t ive n e s s a s a

[image:16.623.98.513.321.604.2]production base.

FIGURE 6.The Dynamics of Minimum Wage, Productivity, and Unit Labor Cost in Indonesia, 2000-2013

Note: unit labor cost is de ined as total compensation (in current prices) divided by real output (in constant prices that is adjusted for increases in output prices). It is assumed that Indonesia's employers pay (or compensate) their workers at minimum wage rate. Unit labor cost gives an estimation on the cost of labor input required to produce one unit of output. The value in the igure above is presented as a relative to its 2000's value.

Source: APINDO's staff calculation based on World Bank-World Development Indicators (2014) and Badan Pusat Statistik (2014)

2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013

7

6

5

4

3

2

1

0

Stop Recrui ng More New Workers for a Certain Periods

Raising the Prices to the Buyers

Inves ng More on the Technology

Reducing the Number of Exis ng Workers

Cu ng Down Bonus

Outsourcing some of the Business Lines to other Companies

Not Relevant

Cu ng Down Budget for Training

Reloca ng Business to the Cheaper Region

Others

0,00% 10,00% 7,55%

20,00% 30,00% 40,00% 50,00% 60,00% 3,21%

16,64% 16,98%

19,81% 23,58%

25,47% 29,25%

42,45%

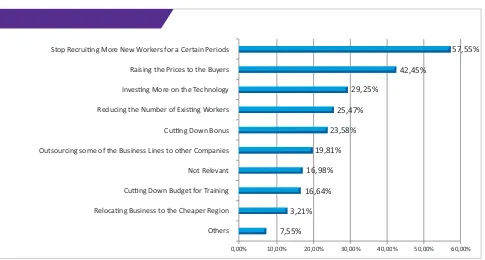

57,55% This study seeks to know deeper on how the

private sector is likely to respond in the case of minimum wage increase. From the survey, we found that majority of the irms being surveyed will respond through: not recruiting more new workers for a certain period, passing the cost increase onto the consumers, and investing more

on the technology (see Figure 7). In the

aggregate terms, it will mean lower employment creation, higher consumer prices (higher in lation), and higher degree of automation (preferring to use machines and technology in the production process

[image:17.623.79.564.316.576.2]rather than laborers). All of this is a response from the private sector to maintain the competitiveness and ef iciency of their irms following the forced increase of wages that is n o t o r i g i n a t e d f ro m p ro d u c t iv i t y improvement. It appears to us that minimum wage will be neutral in its effect to purchasing power, because of likely higher consumers price following that, and possibly aggravate the trend of jobless growth Indonesia is experiencing now via more prevalent automation as it is more costly to hire workers than to invest in machine.

FIGURE 7. How do Firms Respond to Minimum Wage Increases?

Note: the igure is in the percentage to total respondents

Firing the workers and relocating to a cheaper region are not among the irst choice the irms have in mind in responding to minimum wage increase, because it would create another high cost for businesses considering the highly expensive and binding severance payment mandated by labor regulation in Indonesia. In some cases, bringing out a manufacturing plant from Bekasi (west java) to Semarang (central java) might not be viable since employers will have to pay certain amounts of severance payment to the workers in Bekasi that are being dismissed as a response to choosing a lot cheaper workers in central java instead. Indonesia has the highest severance pay level (measured in salary weeks) in the region – it is even higher than that of advanced economies in

Europe and North America Continent. In

average, if employers in Indonesia want to dismiss a worker, they have to pay averagely about 58 weeks of salary, as opposed to employers in major manufacturing economies, like China, which have to pay only equal to averagely 23 weeks of salary.

After all, the government capacity to enforce compliance with minimum wage and severance pay legislation is notably limited, making the labor law ineffective

in protecting the rights of workers. The

World Bank (2010, 2014) reported that the majority of 66% of employees are not receiving severance pay at all when they are dismissed from their works, while 27% employees still received less than the mandated amount. It is estimated that only 7% of employees are receiving full amount of severance pay. In addition, during 2000 to 2011, the non-compliance rate to minimum wage legislation ranges between 30-40%, indicating that not all eligible employees receive minimum wage as mandated by legislation. ILO estimation (2013) further shows that around 36.2 percent employees

in Indonesia earned less than the provincial minimum wage.

Not only do businesses need to comply with expensive hiring and iring cost, they are also facing mounting pressure from the government to comply with rather premature government's social protection programs, namely the BPJS (Badan Pe ny e l e n g g a ra J a m i n a n S o s i a l) i n employment (BPJS Ketenagakerjaan) as well as in healthcare (BPJS Kesehatan). We found that although the majority of the irms have received government-based socialization program regarding the BPJS, they haven't yet fully complied with the regulation. Around 63% respondents admitted that they have been given socialization program from the government, yet 65% of them confessed that not all of their workers have been registered as members of either BPJS in employment

(BPJS Ketenagakerjaan) or BPJS in

healthcare (BPJS Kesehatan).

For those irms, which are not yet fully complied with the BPJS, the average percentage of their workers being registered as members of BPJS in either form is only around 34% for BPJS Ketenagakerjaan and 36% for BPJS Kesehatan. The main reason of why they are not fully complied with BPJS is not that they cannot pay for the insurance premium. Instead, they are more concerned about the clarity of the procedures, the legal certainty, as well as how the BPJS will be overlapping with the existing private insurance scheme the irms already provided for their

employees. Speci ically, many irms

high cost for business because of double p a y m e n t , t h u s h a r m i n g b u s i n e s s competitiveness.

Rigid labor market regulation combined with lack of enforcement, as Indonesia typically does, result in a situation of which everybody is hurt: business becomes increasingly uncompetitive, workers get u n p r o t e c t e d , a n d e m p l o y m e n t opportunities for the jobseekers tend to decrease. It, then, leads towards a lose-lose situation, rather than a win-win one.

Nobody bene its from the system.

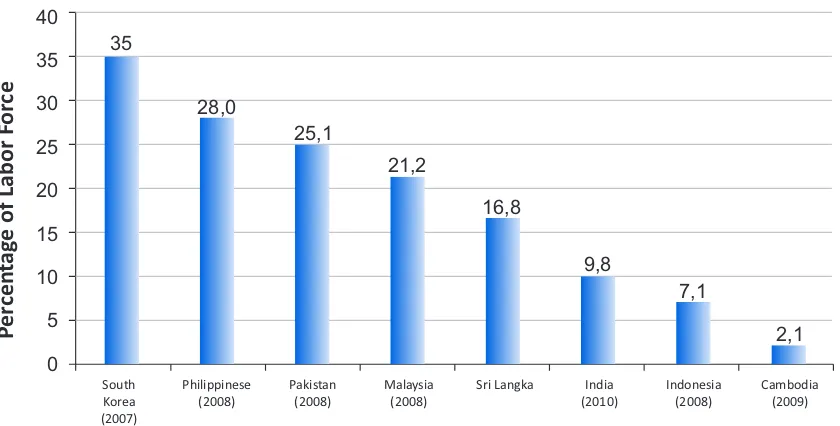

Another element in labor market that is critical to boost country's productivity, enhance business competitiveness in the global market, as well as transform Indonesia into one of high-income countries in the future is the availability of skilled

workforce. In Indonesia, this is quite an

issue. Indonesia still has a relatively small

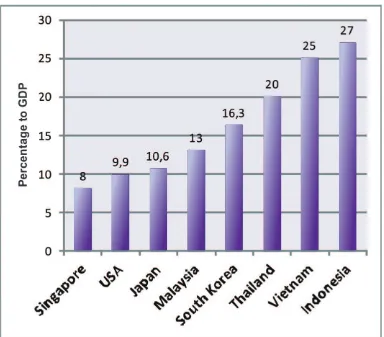

size of labor pool equipped with tertiary education (post-secondary education, including academy, university, college, etc.). In this education level, workforces are equipped with relevant analytical and technical capabilities necessary for middle to higher skilled jobs. Based on the latest World Bank data, only 7.1% labor force in Indonesia is having tertiary education. This igure is very low as compared to other developing-manufacturing countries, which are essentially Indonesia's closest competitors in the global manufacturing markets, such as Malaysia (21%), Philippines (28%), as well as Pakistan (25%) and Sri Lanka (17%) for lower-value added market (see Figure 8). Indonesia is only better than the less-developed countries, namely Cambodia. As Indonesia aspires to be one of high-income countries in the future, it is worth to use South Korea as a model, where 35% of its workers are already receiving tertiary education.

[image:19.623.104.524.442.655.2]Source: World Development Indicators, World Bank Data (2014)

FIGURE 8. Percentage of Labor Force with Tertiary Education (% of total)

40 35 30 25 20 15 10 5 0

South Korea (2007)

Philippinese

(2008) Pakistan(2008) Malaysia(2008) Sri Langka (2010)India Indonesia(2008) Cambodia(2009)

Per

cen

tag

e of Labor F

or

ce

35

28,0

25,1

21,2

16,8

9,8

7,1

The shortage of skilled-labor in

Indonesia has been evident nowadays.

From the APINDO's survey, we found a majority of 59% respondents saying that they have dif icult times in inding skilled workers, especially the middle-skill workers⁴. The dif iculty in inding the middle-skill workers, as compared to the condition of 3 years ago, has been perceived as remain unchanged by majority of 44% respondents, while the other 29% feel an increasing dif iculty; only a minority of 27% respondents saying that it's been easier to ind so. The data that we found from professional association has a similar tone with our survey indings. For instance, in engineering services, Indonesia is predictably lacking of around 1.2 million engineers, which is attributed to the low growth rate of engineering graduates in Indonesia (164 graduates per year per million of people) as compared to other developing countries, like Malaysia (367 graduates per year per million of people). As for nursing services, if Indonesia fails to increase the ratio of nurse per population from currently low 1:2850 to ideally 1:851, there would be a shortage of 87,618 nurses in relative to the potential demand by 2019 (Keliat, et.al, 2013).

A more macro data by the World Bank and BPS estimated that by 2025, Indonesia would experience a shortage of 10 million of s k i l l e d l a b o r s . G i v e n h i g h y o u t h u n e m p l o y m e n t a n d e d u c a t e d unemployment rate in Indonesia, which is around 22% and 9% respectively (as c o m p a r e d t o a v e r a g e n a t i o n a l unemployment rate, which is around 6%,

and youth and educated unemployment rate in other countries⁵), it gives us a sense that

it's not only about lacking the number, but more importantly also lacking the

quality, e.g. the skill doesn't match to the

updated need of the market, the skill of the graduates is still in the low quality, etc.

It has been a common perception in the business community that the skill pro ile of Indonesian workers has not evolved along with the demands of the labor

market. The problem clearly doesn't

originate solely from poorly performed formal education sector, but also from the ill functioning of the informal education offered by the companies, i.e. on-the-job training, which is often more useful, practical, and critical for workers' skill acquisition. Early indications are pointing out that rigid labor market regulation might have something to do with lack of training and education being offered by

private sectors. Labor regulation is deemed

to focus too heavily in the protection side, which it never does because of lack of enforcement, yet fails to incentivize and stimulate employers to provide training critical for workers' productivity improvement. The key is in the more active engagement from the private sectors as well as government's will to provide inancial incentive and support for the improvement of training capacity and quality in the private sectors and designated national training center (“Balai Latihan Kerja”/BLK).

The skill that requires a training and technical capability at the level more than a high school diploma, but less than a four-year university degree

4

5

C.3. Infrastructure and Logistics

Logistics infrastructure is a

serious problem in Indonesia

.

Respondents perceive it as the major impediments for business competitiveness, as well as the least improving and the least competitive elements of competitiveness as compared to the situation in other developing countries in Asia. The quality of infrastructure, logistics, and transportation in Indonesia in several global rankings is ranked unsatisfactory, which is still well below the ranking of other major developing countries in ASEAN such as Malaysia and

Thailand. Even worse, the World Bank's Logistics performance Index (LPI) shows that Indonesia is currently placed 53 out of 160 countries. Even though there are improvements, Indonesia's LPI is still below Vietnam, which has become a tough competitor for manufacturing production base in ASEAN region. Logistics and i n f r a s t r u c t u r e s a r e v i t a l f o r t h e competitiveness of manufacturing sectors, especially the export-oriented ones. The limitation of logistics infrastructure hinders national manufacturing supply chain, thus hampering business

[image:21.623.76.563.361.666.2]productivity and competitiveness.

FIGURE 9.Major Problems in Trade Logistics Issues that Hampering Firms' Trade Activity

Note: the igure is in the percentage to total respondents

Source: Author's calculation based on APINDO's survey on business competitiveness (2014)

0,00% 10,00% 20,00% 30,00% 40,00% 50,00% 60,00% 70,00%

Percentage of Respondents Process and Procedures in Customs and other

Conges on

Limited Applica on of ICT in Trade Ac vity

Poor Quality of Roads and Bridges

Poor Quality of Port and/or Airport Infrastructure

Long Dwelling Time

Lack of Quality and Reliable Logis cs Services and Experts

Poor Quality of Logis cs Suppor ng Infrastructures

Lack of Quality and Reliable Transport Services Providers

Others related Ins tu ons

(e.g. warehouse, cold storage, etc)

Through this study, we would like to identify where actually the problems lie. The irst major problem is related to the

institutional infrastructure. The majority

of 64% respondents rated the lengthy and complicated process and procedures in the customs and other related institutions as their major impediments to trade (see Figure 9). This gets worsened by the fact that the application of ICT in trade activity is still notably limited. For instance, many export/import documents cannot be uploaded via online and still require the traders to come to the several trade-related institutions which can be very costly to them. The Indonesia's National Single Window (NSW) system was established to address these institutional issues by placing all the related institutions into one location. However, it hasn't worked quite effectively. The majority of 61% respondents expressed that the Indonesia's NSW has not worked effectively. The NSW doesn't work the way it supposed to be, if not ineffective at all.

The second problem lies at the poor quality of physical infrastructure in

Indonesia. Deliver y of goods from

production center to ports/airports is highly inef icient in Indonesia compared to

neighboring countries in ASEAN. For

example, in Malaysia, transportation from Pasir Gudang production center to Tanjung Pelepas Port within 56.4 Km takes 1-2 hours and needs cost in an amount of USD 450 per container. Meanwhile in Indonesia, transportation from Cikarang production center to Tanjung Priok Port within 55.4 Km takes much longer time of 4-8 hours and requires higher cost of USD 600 per container (APINDO, 2014). What makes distribution in Indonesia more expensive than in Malaysia is that congestion is m o re s eve re a n d t h e q u a l i t y o f infrastructure is poorer in Indonesia

than in Malaysia. Almost half of the

respondents rated congestion as the second major impediments to their trade activity (after customs problem), while 34% respondents feel that poor quality of roads and bridges is hampering the trade processes. With highly congested and damaged roads, it is then expected that moving out goods to another center point will be more expensive and takes longer time. This then will create not only expensive delivery cost, but also delivery uncertainty and unpunctuality, which is further creating

disturbance for the whole supply chain system and forcing the irms to bear higher inventory cost, thus repressing

Indonesia's logistics cost could be up to 27% (see Figure 10), yet its service

quality is still very poor. This cost is higher

than those of other major developing countries in ASEAN, like Malaysia (13%) and Thailand (20%), and still more expensive than Indonesia's closest competitor in manufacturing products, namely Vietnam (25%). From the survey, we also found that the logistics cost tend to be more expensive over time, while the quality of transportation and infrastructure remain unchanged. Almost 80% of respondents said that their logistics cost as a relative to the irms' total cost has increased as compared to the

condition of 3 years ago. Most respondents also see no signi icant improvement in the quality of transportation system and infrastructure (see Figure 11). The increasing logistics cost might arguably be a re lection of infrastructure development failing to keeping up with

the fast pace of economic progress. Hence,

[image:23.623.128.512.113.450.2]more truck are entering the unchanged roads capacity, more containers are shipped via more crowded ports and/or airports, thus longer lead-time and higher cost because of congestion in many points.

FIGURE 10.Logistics Cost: Indonesia Vs. Selected ASEAN and Advanced Economies

Worse/More Expensive (for Logis cs Cost) Unchanged Be er 100%

90%

80%

70%

60%

50%

40%

30%

20%

10%

0%

Per

cen

tag

e of R

esponden

ts

Logis cs Cost

20,75

79,25

Quality of Transporta on System

36,54

79,25

Quality of Infrastructure

20,75

79,25 53,85

[image:24.623.154.485.118.359.2]9,62 15,24 51,43

FIGURE 11. Logistics Cost, Transportation and Infrastructure Quality,

as Compared to 3 Years Ago

Note: the igure is in the percentage to total respondents

Source: Author's calculation based on APINDO's survey on business competitiveness (2014)

Apart from the trade logistics issue, there is another more essential and profound problem regarding the infrastructure in Indonesia, namely the electricity. The percentage of people having access to the electricity is still very low by developing countries standard (see Figure 12). Only 73% of Indonesia's population in 2011 has access to electricity; this means there are more than 60 million of lives that still don't have access to the electricity. This igure is very low as compared to those of Malaysia, China, and Thailand where almost all their citizens have already had access to electricity.

The issue on electricity in Indonesia should not be viewed only in term of the coverage, but more importantly also in term of the quality. The APINDO survey found that almost all the irms have experienced blackout, at least once in a month. Averagely,

It is worth to analyze the issue on electricity region by region. We found that the incidence and the cost of blackout have been higher in Medan than in other parts of Indonesia that were being surveyed. Re s p o n d e n t s i n M e d a n i s u s u a l ly experiencing 30 times blackout per month, meaning that almost everyday they have to deal with the blackout. For 3 hours long of every blackout, it is costing private sectors in Medan up to 20% of their irms' annual sales (see Figure 13). This brings up a negative effect to manufacturing development in Medan in a signi icant amount. As national and regional governments strive to develop downstream manufacturing base for agriculture and forestry sectors in Medan, there is a pressing need to signi icantly and immediately boost the quality of electricity in Medan. Without reliable electricity access,

the manufacturing plant cannot be operated, thus making Medan to continue highly rely on its primary activity and natural resources, and further get left behind by other regions in term of development status. This applies also for other regions aspiring to improve their welfare; reliable electricity access is an important determinant for inviting in manufacturing plant critical for boosting

[image:25.623.136.505.105.382.2]up the region's development.

FIGURE 12. Access to Electricity, Year 2011

D. Business confidence and

moving forward beyond

2015

This section provides survey analysis on how Indonesian businesses perceived their con idence in moving forward to ASEAN Economic Community (AEC) 2015 and their ability to compete with businesses from other countries three years from now. There are also several recommendations on respondent's perspective of the role of new government toward their con idence in doing business for the coming years.

D.1. Indonesian businesses are ready to face tighter competition in AEC 2015

Given the fact that AEC 2015 will be implemented next year means the competition among businesses will increase

tremendously not only domestically but also regionally in particular for ASEAN countries. Only 8,5% of respondents who disagree by having told they are ready to face tighter competition in AEC 2015, but over 45% of interviewees believe their businesses are ready to compete with other ASEAN countries next year. This result shows that

Indonesian businesses currently have high con idence in the quality of their products and services to be compared with products from other ASEAN

countries. In addition, this con idence can

[image:26.623.104.524.107.363.2]be driven as well by their major experiences in doing export therefore most of respondents assumed their competitiveness can be challenged toward AEC 2015.

FIGURE 13. Blackout in Medan as Compared to other Regions

Source: Author's calculation based on APINDO's survey on business competitiveness (2014)

35

30

25

20

15

10

5

0

A l t h o u g h t h e A E C 2 0 1 5 i s n e a r ly approaching, there are several policy recommendations can be taken to perform by both government and business sector in Indonesia. Changing the operating model is one of steps that can be followed by private sectors by looking at new, lower cost operating and delivery models. This can be achieved by considering channels to market, new distribution and production partners, and new internal operating model, which focus on the goods and services which customers want. Furthermore, refocusing

on what the customers really value by

re-examining the goods, services and propositions that are offered. Through checking how existing goods and services meet changing customer requirements there is the opportunity to re-designing those offerings so that they cost less to produce and deliver.

Additionally, there are several actions should be delivered by government to equip private sectors in competing with other ASEAN countries for instance to provide information to SMEs about opportunities from AEC 2015, educate them on utilization of FTAs privileges, provide them with useful network, access to inance, and most importantly is to help them in building their technical capacity particularly to businesses who have lack “culture of competition” so they will be able to compete and gain maximum pro it from the bene it of AEC. Moreover, Geoff Riley (2012) stated when business con idence is strong then planned investment will rise. Thus, investment policies and regulations should be restructured, harmonized and standardized by new government in order to create more investment-like business environment in Indonesia.

D.2. Perception on the effect to

Indonesian business sector if

FTA between Indonesia and

European Union is being

implemented

International trade is the modern framework of prosperity. It leads to policies creation which opens up new areas to competition and innovation. 48% of respondents con irm that FTA/CEPA between Indonesia and European Union will positively affecting their businesses. This indicates most of respondents have recognized the advantages of free trade agreement that initiates better jobs, new markets and increased investment. Secondly, this result also illustrates the trust rate of Indonesian private sectors to European Union is high as EU was ranked as the fourth largest source of import and the third largest export destination for I n d o n e s i a' s p ro d u c t s ( L a k s o n o & Situmorang, 2014, p. 8). It is an evidence for r e s p o n d e n t s t o b e l i e v e t h a t F TA implementation with EU will bring greater b ene its fo r Indo nesian

companies. There are only sixteen out of

D.3. Business Prospect: Politics

and Global Situation

Over 76% of businesses surveyed in this report perceived the election held in last July 2014 were running well and conducive, but it is a task to newly elected government to create more reliable and conducive environment to business climate in order to reach higher competitiveness of Indonesian economic situation.

This result implies that the presidential election has boost up business con idence and enforce the Indonesian irms to improve their business activities in upcoming years. As Stephen B. Kaplan stated business con idence could be correlated positively with election timing (2006, p. 22), then it can

be referred to the survey result which indicate not only the election was held in the right time but most importantly it can be seen there is high expectation from business community to the new Indonesian government. Business community in Indonesia believes they will be able to expand their businesses under new

regime. Hence, aiming maintain growing

[image:28.623.106.560.207.351.2]business con idence, new government need to speed up in improving business environment and investment climate.

FIGURE 14.Projection on the Effect of FTA Implementation between Indonesia and the EU

Source: Author's calculation based on APINDO's survey on business competitiveness (2014)

0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50%

Very posi vely affec ng my business

Posi vely affec ng my business

Neutral

Nega vely affec ng my business

Very nega vely affec ng my business

Very significant

Promising

No improvement

Not really sure

Not sure at all

0,00%

20,00%

40,00% 60,00%

Forecast on Business Prospect

in 2015 under New Government Role

Furthermore, the graph shown above has also emphasized more that business con idence among Indonesia business sectors nowadays is very high. There are in total 65% of respondents perceived the business prospect in 2015 is promising.

R e s p o n d e n t s b e l i e v e t h a t n e w government will bring positive impacts to national business and economic

development. This is a momentum for

government to capitalize the business con idence in Indonesia to attract higher investment rate that can contribute to faster income growth the government aspires at.

In term of business prediction, as a result of the globalization process world businesses are increasingly affected by the actions of international competitors. A number of

[image:29.623.140.488.190.371.2]international trade agreements have encouraged businesses around the world to strive and to be prepared in order to be successful in global competition. 51% of total respondents believe that the ability of Indonesian irms competing in global markets is becoming better within the next three years. This result indicates that most of businesses in Indonesia have suf icient resources and dependable business strategies to be engaged in global competition, a situation that businesses should respond of in order to enjoy global economies of scale. The burden of not developing a global business strategy is that you will come off second best in competing with the big global companies

FIGURE 15. Forecast on Business Prospect in 2015 under New Government Role

Moreover, in facing the global competition it is a positive approach to identify your competitive advantages therefore you will ensure your company remain competitive in increasingly competitive market place. Companies achieve competitive advantage through acts of innovation (Porter, M. E. 1990). They approach innovation in its broadest sense, including both new technologies and new ways of doing things. Innovation can be manifested in a new product design, a new production process, a new marketing approach, or a new

[image:30.623.150.485.393.551.2]way of conducting training. Moreover, structured approaches to business improvement namely quality improvement and operational costs reduction are essential as well to be implemented. Sustainability is also has become an essential element of competitive advantage w h i c h m o s t ly e n c o m p a s s e s t h re e d i m e n s i o n s a s i n a n c i a l s t a b i l i t y, environmental sustainability, and social sustainability.

FIGURE 16. Forecast on the Ability of Indonesian Companies to Provide Employees with

Higher Wage and Bene its within the next three Years

Source: Author's calculation based on APINDO's survey on business competitiveness (2014)

In addition, as can be seen on the chart shown above, there are 39% of interviewees believe that three years from now irms in Indonesia are able to afford higher salary and bene its to their employees. According to this result, it is indicating clearly that Indonesian company optimist their businesses will much improved within the

next three years and yield greater pro it. There are only 19% of respondents who predict Indonesian businesses will remunerate their employees with lesser rate and bene its within the next three years.

Much Be er

Be er

Same

Worse

Much worse

0

10

20

30

40

Forecast on the Ability of Indonesian Companies

to Provide Employess with Higher Wage and

1. To remove red tape in business licensing, permit and other regulation related to business

This may include policy breakthrough such as:

o Online processing for all business licensing both for national and regional level (e.g. SIUP, TDP), permit (e.g. import quota, CoO, etc), and other regulation (e.g. certi icate from Ministry of Law and Human Rights, etc), with zero fee, no price discrimination, and speedy service

o Expediting the realization of One Stop Shop for investment and business licensing

o Improving the institutional quality of government's agency especially in the ield of trade, industrial and SMEs in every region (provinces, city, and municipality)

2. To improve legal certainty, through

o Establishment of task force team to identify and provide recommendation to the government regarding harmonization of laws at all levels (national, provincial, city, and municipality level). This may require alignment, adjustment, or annulment of laws and regulation that are overlapping, or no longer relevant in present time

o Involvement of business player and other related stakeholders during each legislation process that relates with business activities

o Centralization of online database containing laws at both national and sub-national levels that is accessible by the public

o Enhancement of law enforcers' professionalism in addition to technical knowledge in order for them to also understand economic standpoint when implementing their duties. Their actions/decisions should never impede favorable investment climate

3. To develop priority infrastructure projects in order to reduce logistics cost and

improve connectivity both globally and domestically, through:

o Developing industrial cluster close to seashore based on SME cluster and is connected with global supply chain, particularly in Central Java, northern area of East Java, Lampung, and Southern area Kalimantan

D.4. Policy Recommendation on

S t r e n g t h e n i n g B u s i n e s s

Competitiveness

There is a golden opportunity for Indonesia both to boost the income of its people and leading the global manufacturing market. However, Indonesia only has one time window of opportunity, before demographic dividend will be stopped by 2030 and Indonesia's wage rises too fast that it b e c o m e s n o l o n g e r a t t ra c t ive fo r manufacturing base. If Indonesia fails to optimize the opportunity, it would be there

for other competitors, like Vietnam, Bangladesh, and other less-developed countries, to tap into this golden opportunity and using it to leapfrog Indonesia sometime in the near future.

o Replace goods