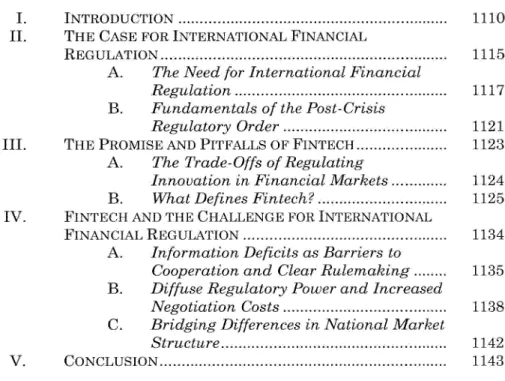

This article shows that fintech is exacerbating the difficulties in setting standards in international financial regulation. International financial regulation poses even greater challenges when viewed through the lens of the Trilemma. From an international financial regulation perspective, a lack of novelty means that regulators can look to the mechanisms established by the post-2008 international regulatory framework to promulgate fintech standards (if they are really needed) and to enforce compliance motivate.

Finally, the article shows that international financial regulation for fintech requires the creation of standards capable of overcoming national market structures that are experiencing in different ways disintermediation and increased complexity within financial supply chains. In conclusion, this article briefly outlines initial ideas to help navigate the new challenges posed by fintech to international financial regulation. establishing the foundations of international financial law and the mechanisms that help strengthen its soft character) [further Brummer, How International Law Works]; David Zaring, The Internationalism of Financial Reform, 65 EMORY L.J.

Fundamentals of the Post-Crisis Regulatory Order

See generally BRUMMER, MINILATERALISM, supra note 24 (describing how international financial regulation can be more concrete than it seems); Brummer, How International Law Works, supra note 28.

Such tenacity reflects the ability of large global corporations to act as transmission channels for legal change. 6 6 Specifically, periodic reviews by the IMF and the World Bank increase accountability for domestic regulators by publicly advertising the outcomes of regulators' benchmarking assessments.6 7. For example, national legal systems differ in how they format reporting requirements for derivatives , the composition of protective resource buffers for financial institutions such as clearinghouses, and calibrating the scope of activity restrictions for banks.68 In addition, supervisory conventions may depend on factors such as a country's internal administrative resources for financing national supervisors, the legal system and relationships between the regulator and supervised firms.69 However, as evidenced by the widespread adoption of key regulatory standards following the crisis, international financial regulation has had a lasting economic impact on financial markets, affecting capital allocation and the way capital flows between jurisdictions flows. ATLANTIC COUNCIL, supra note 25, 36-44; see also Dermot Turing & Yesha Yadav, The Extraterritorial Regulation of Clearinghouses, 2 J.

For the most part, regulators have been caught flat-footed.7 0 Faced with this post-crisis surge of innovation, they have been forced to confront, in short order, complex questions about the implications of these new technologies for existing regulation.7 1 Is fintech really so different from previous cycles of innovation that current rules are ill-adapted to control its risks and exploit its opportunities. Fintech creates new externalities for financial markets that contemporary regulatory paradigms do not address. This part briefly introduces and analyzes these changes and the challenges they pose for regulators.

In this regard, the following discussion summarizes arguments advanced in previous work that argue that fintech represents a truly new category of innovation that differs from previous iterations of technological development in financial markets.7 2 It suggests that fintech creates unique difficulties for international regulators that the post-2008 framework is currently. The balance of regulation of innovation in financial markets Innovation represents a constant stock of capital markets. See generally Brummer & Yadav, supra note 6 (introducing the fintech trilemma and defining three new factors that constitute the salient features of today's fintech).

But previous work argues that fintech actually presents a new kind of innovation whose distinctive permutations represent a break from previous cycles of market ingenuity. This prior work introduced the Innovation Trilemma to capture the trade-offs regulators face as they balance the goals of encouraging innovation, protecting market integrity, and legislating through clear rulemaking.7 5. Of course, regulators must juggle a host of other considerations, eg. such as securing administrative legitimacy or addressing national or international political concerns.

What Defines Fintech?

Ilana Polyak, Millennials and Robo-advisors: A Match Made in Heaven?

One solution here would be to consider big data as a remedy to overcome the information deficits created by smart algorithms. As previous work shows, reliance on big data represents a further defining characteristic of fintech.1 06 Algorithms require data to function. Algorithms are able to aggregate social media sites and mine GPS data, online shopping habits, social contacts and weather patterns – so-called alternative data points that can amplify information conveyed by more familiar sources such as balance sheets, profit and loss statements, price quotes. related information from trading markets or routine business information." 0.

This proliferation of big data can provide powerful fuel for smart algorithms as a way to make financial services more accurate, calibrated and responsive to signals contained in a mix of information. Within online lending, big and alternative data are e.g. widely touted by fintech lenders as a basis for ensuring that loans more accurately and fairly reflect borrower risk. By observing factors such as social contacts, online shopping habits or the quality of punctuation in a borrower's text messages, lenders claim that big data and sophisticated algorithms can help.

For detailed discussion, see generally KENNETH NEIL CUKIER & VIKTOR MAYER-SCHOENBERGER, BIG DATA: A REVOLUTION THAT WILL TRANSFORM HOW WE LIVE, WORK AND THINK (2013). Similarly, in the securities markets, investors are paying a lot for alternative data feeds as a means of getting that all-important edge. Without question, big data holds the promise of huge benefits for market participants as well as for regulators seeking to gain detailed insight into market behavior.

Without more evidence and a long-term history of use, regulators and market participants cannot credibly determine the effectiveness of big and alternative data for capital allocation purposes.11 7 More precisely, the emergence of completely new types of data such as media sources, mobile phone contacts or online shopping habits they represent an innovative new frontier in risk measurement, the evidentiary utility of which remains largely unknown for the time being. 2 8 While big data can go some way to addressing the deficit, it is far from a panacea.

FINTECH AND THE CHALLENGE FOR INTERNATIONAL FINANCIAL REGULATION

First, as highlighted in previous work, fintech complicates the usual trade-offs involved in the trilemma of balancing innovation, market integrity and regulatory simplicity. Finally, the goals of regulatory clarity and financial innovation are particularly difficult to achieve when national markets differ in the extent to which new firms and technologies structurally disintermediate their home markets. In this regard, regulators could rightly be concerned about the quality of data used by fintech innovators.

Within such a complex ecosystem, innovation can be susceptible to failures at various parts of the supply chain. Regulators in country Z may not be fully aware of the costs of their decision-making, as the innovations they license are transferred to different national market ecosystems. These information deficits—and the analytical costs of understanding how fintech innovations differ based on how they operate in different markets—hinder a true understanding of the risks they pose to global market integrity.

The complexities of applying the Trilemma to fintech, especially in a cross-border context, highlight the need for international regulators to cooperate and coordinate in setting and enforcing standards. However, the impetus for post-crisis financial regulatory reform is still fixated on the problems arising from the fallout in the United States and the European Union as a basis for setting the reform agenda. For historically underdeveloped markets without a sound payment system, reliable banks or affordable credit, fintech can help fill gaps in the availability of financial services.

In particular, the varying distributive impact of fintech innovations – and their ability to fill gaps in the availability of local financial services – complicates the difficulty. Such new entrants have dismantled the services offered by conventional financial companies (for example in online lending, payment processing or wealth management) and improved financial supply chains by offering easy-to-use products such as digital wallets. In other words, national markets vary in the extent to which traditional financial products, services and businesses have been structurally influenced by fintech.

In addition to information deficits, divergences in national legal systems, and higher negotiation costs, a new and more diverse group of financial firms further complicates the task of navigating the poles of the Trilemma in international financial regulation.

CONCLUSION

International financial regulation further compounds this difficulty as standards must be sufficiently flexible and adaptable to oversee national markets at various stages of fintech adoption. The depth of fintech adoption and the degree of structural change underway in different markets increases the difficulty of creating standards that are globally acceptable and capable of widespread implementation. This earlier work argued that the singular characteristics of fintech complicate these already difficult trade-offs.

Finally, international regulation must take into account differences in national market structures that vary in the adoption of fintech and the extent of disintermediation underway within their economies. This reduces the ability of international regulation to achieve regulatory clarity, as standards must apply to a more diverse set of national market environments, each of which is distinctive in the adoption of fintech products and services. It is fair to say that international technocratic bodies such as the FSB, IOSCO and the Basel Committee have attempted to engage in the field of fintech.163 They have provided valuable research and advice on this topic.

For example, digital wallet providers may be well placed to more easily build infrastructure across borders where countries are close together. Algorithms may be easier to adapt to countries whose narrow borders mean that programmers have greater knowledge of local customs, financial habits and market participants. Consequently, countries may be better placed to negotiate with each other if they are already well used to doing so on matters of regional importance.

They may be unwilling or unable to acknowledge the risks they are likely to create, develop standards that benefit them at the expense of entrenched competitors, or underestimate the costs of collective behavior. See Price, supra note 138 (discussing the intense competition among fintech regulators in the Asia-Pacific region).