1

Introduction

To date Life Cycle Assessment (German: “Ökobilanz”) is a method defined by standards ISO EN 14040 and 14044 to analyse environmental aspects and impact of product systems. Introduction of the method in

chapters 2 to 5 therefore relates to these standards. As preliminaries, scope and development of the method are introduced in this chapter.

1.1

What is meant by Life Cycle Assessment (LCA)?

1.1.1

Definition and Limitations

According to our knowledge, the German term Ökobilanz, in the sense of

“ecological balance” or later named life cycle assessment, (LCA), was initially used in a study by the Environmental Confederation Agency of Switzerland

1. This study had a great influence on the issue, especially in German speaking countries and from here results the colloquial expression which is more adequately termed Life Cycle Assessment in English.

In the introductory part of International Standard ISO 14040

2serving as framework, LCA is defined as follows:

“A life cycle assessment (LCA, also known as life cycle analysis, ecobalance) is a technique for an product related estimation of

environmental aspects and impact … LCA assesses each and every impact associated with all stages of a process from cradle-to-grave (i.e., from raw materials through materials processing, manufacture, distribution, use, repair, maintenance, and disposal or recycling.”

A similar definition of LCA had been adopted as early as 1993 by the Society of Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry (SETAC)

3in its

1German: Schweitzer Bundesamt für Umweltschutz; BUS, 1984

2ISO 1997

3 Foundation year 1979

“Code of Practice”

4.

Similar definitions can be found in basic guidelines of DIN-NAGUS

5as well as in the “Nordic Guidelines”

6commissioned by Scandinavian Ministers of the Environment.

Those deliberate limitations of an LCA to analysis and valuation of

environmental impacts has as consequence that the method is restricted to only quantify

7one, an ecological, aspect of persistence (see Chapter 6).

The exclusion of economical and social factors separates LCA from product line analysis (PLA) and similar methods

8. This separation was made to avoid a method overload being aware of the fact that with a development of persistent products these factors cannot and must not be neglected

9.

1.1.2

Life Cycle of a Product

The main idea of an analysis cradle-to-grave or life cycle is illustrated, simplified, in Fig 1.1. Starting point for building a product tree is the production of an end product plus the phase of operation. Further

diversification of the boxes in Fig. 1.1 into singular processes, so called process units as well as the inclusion of transports, diverse energy supply, by-products, etc. turn this simplistic scheme even with simple products into very complex “product trees” (diverse raw material and energy supply, interim products, by-products, waste management including diverse

disposal types or recycling).

<<Fig.1.1>>

Fig. 1.1 Simplified life cycle of an (industrial) product

Interconnected process units (life cycle of product tree) form a system. At the centre will be a product, a process, a service or human activity

10- in the widest sense. In an LCA, systems serving a specific function and which therefore have a benefit will be analysed.

4 SETAC 1993

5 DIN-Normenausschuss Grundlagen des Umweltschutzes (NAGUS), Germany, 1994

6 Lindfors et al. 1995

7 Klöpffer 2003, 2008

8 Projektgruppe Ökologische Wirtschaft 1987; O‘Brien et al. 1996

9 Klöpffer 2008

10 SETAC 1993

Therefore the benefit of a system will be the actual factor of

comparison for a comparison of products. It is regarded as the sole correct basis for the definition of a “functional unit”

11.

1.1.3

Functional Unit

Besides an analysis cradle-to-grave that is thinking in systems, life cycles or production trees, the functional unit is the other basic term in an LCA and should therefore already be explained here:

The benefit of a beverage packing is besides a shielding of the liquid above all transportability and storability. A functional unit will most

frequently be defined as an eligibility of 1000 L liquid in a way to obtain a technical supply of benefit. This function can for instance be mapped as follows with packing specifications arbitrarily chosen:

- 5000 0.2 L

12sachets

- 2000 0.5 L reusable bottles of glass - 1000 1 L single-use beverage cardboard - 500 2 L PET single-use bottles

Thus, for a comparison of packing systems, the life cycle of 500 barrels, 2000 bottles, 1000 cardboards and 500 2 L PET bottles needs to be

analysed and compared, or four systems serving roughly the same benefit.

Slight variations of benefit (convenience, e.g. weight, customer orientation, aesthetics, performance, advertising and other commercially exploitable side effects) do not have to interfere in the simplistic example. It is important to note that systems (not products) with similar benefit are compared

13. By this it is also possible to compare industrial products

(goods) with services, as long as they have a same or very similar benefit.

Within a LCA, products are defined as goods and services. As with

products, services require energy, transport, etc. Therefore it is possible to define services as systems and to compare them with industrial product systems on the basis of equivalent benefit by means of the functional unit.

11 Fleischer and Schmidt 1996

12 1L = 2.1 PT

13 Boustead 1996

1.1.4

LCA as System Analysis

Differently put, a LCA is based on a simplified system analysis.

Simplification consists of extensive linearisation (see system boundary and cut-off criteria in Section 2.2). Interconnections of parts of the life cycle of a product which always exist in reality, lead to extremely complex

relationships in the modelling. There are nevertheless possibilities to

handle the formation of loops and other deviations from linear structure e.g.

by an iterative approach or matrices calculus

14.

Example

LCA deals with a comparison of product systems not products. What is meant by this?

Within the product segment towel dispenser, paper towels and fabric caster are distinguished. The fabric needs to be cleaned to fulfil its

function. This means, the cleansing process (detergent, water and energy consumption) is part of the product system and must surely be

considered. Washing machines must be applied for cleaning.

Does the production of washing machines also have to be considered?

They are made of steel which is assembled of ore which needs to be produced etc. Limitations are therefore necessary. On the other hand nothing essential may be omitted.

System analysis and the selection of system boundaries are therefore important tasks within a LCA.

The main advantage of this approach lies in its abilities to easily detect deferrals of environmental loads, so called trade-offs, which for example occur within substitutions: it is of no use if environmental loads are

seemingly eliminated if, later on or at different places, in different life cycles or environmental media additional problems will occur, or if an unrelated entry or resource consumption is involved.

It is not arguable that in rare cases especially in health threatening circumstances (e.g. substitution of hazardous substances) decisions categorized as suboptimal must be made.

14 Heijungs 1997; Heijungs and Suh 2002

Example

As fossil resources diminish, substitution of raw material by renewable resources is an objective of science and development.

By LCA, variants of loose-fill packing substances such as polystryol and potato starch

15have e.g. been examined As production processes of both material fundamentally differ, a thorough analysis is necessary. For

instance, the overall agricultural system including growth, maintenance, and harvest needs to be considered during the production of raw material, in the other case the raw oil production. Other life cycles of loose-fill packings differ depending on type of raw material. It cannot be decided at first sight whether substitution on the basis of raw material will have an ecological advantage or not.

1.1.5

LCA and Operational Life Cycle Assessment

There is always a risk of problem shift if spatial boundaries and those of time have been over restrictive. This is often the case, if only operational life cycle assessments (misguidedly termed ecobalance of the enterprise or ecobalance without supplementary explanation) have been conducted. If for instance the system boundary is set equal to site of the enterprise, an adjustment to the fundamental concept of LCA is not made: Neither the production of deliveries nor their disposal is considered. Transports, outsourcing and parts of waste removal will not be accounted.

Example

Pseudo Improvement by Outsourcing

The manufacturer of fine foods had intended not only to advertise his products based on taste and salubriousness but also by environmental aspects. For this, data concerning energy and water consumption was procured in an operational life cycle assessment to allow an allocation of the salad composition. Potato salad had an immense water supply, the

15Bifa/IFEU/Flo-Pak 2002

reason being that potatoes were usually covered by earth and had to be cleaned. The waste water was then assigned to the potato salad. Some weeks later water supply per salad had drastically diminished. This was not due to an innovation on the cleansing gadget but because the washing had been outsourced to another enterprise. For this reason washing water did not occur in the operational life cycle assessment

Nevertheless operational life cycle assessment may for many applications be useful, for example as data base in an environmental management system

16.

A simple consideration shows that operational life cycle assessments provide data bases for product life cycle assessment: every process for the production of e.g. 500 g potato salad in screwed cap glasses takes place at a specific place at a specific time. If data, e.g. for energy and water

consumption of the system “1000 screw cap glasses, each containing 500g potato salad, cucumber, egg and yoghurt dressing” has to be procured, every company that is part of production and transport of the packed

product as well as businesses for waste disposal, must have their processes analysed in such a way that these could be allocated to the original product.

This is not trivial: an agricultural corporation, generally does not only produce milk, dairies not only yoghurt, the manufacturer of glass

manufactures provides glasses for diverse customers, etc. If all entities involved in the manufacture of the product already disposed of a LCA containing product related data, these results could be merged. Product related data acquisition is nevertheless not common practice in operational life cycle assessments.

Coupling of such operational life cycle assessments along the life cycle of products would provide the possibility of chaining of agents

17. Agents that are part of a product system could detect and realize a common potential for optimization. A new state of mind inclined to thinking and, by far, acting in life cycles (Life Cycle Thinking and Life Cycles Management – LCM) may emerge.

1.2 History 1.2.1

16Braunschweig and Müller-Wenk 1993; Beck 1993; Schaltegger 1996

17 Udo de Haes and De Snoo 1996, 1997

Early LCAs

Life Cycle Assessment is a recent technology but not as recent as many believe. There are approaches to life cycle thinking in literature. Scottish economist and biologist Patrick Geddes has as early as in the 80s of 19th century developed a procedure which can serve as precursor for LCA

18. His interest was focused on energy supply, especially of coal.

First LCAs in the modern sense were conducted around the 1970s termed

“Resource and Environmental Pacific Analysis (REPA)” at Midwest Research Institute in the USA

19. As with nearly all early LCAs or

“proto-LCs”

20these were an analysis of resource consumption and releases of product systems, so called inventories without impact

assessment. To date such studies are mostly called life inventory-LCA studies

21. The new comparative method was first applied for a comparison of beverage packing. The same applies for the first LCA conducted in Germany

22. The latter was done under an administration of B. Oberbacher in 1972 at the Battelle-Institute in Frankfurt. The method developed by Franklin and Hunt was applied with an additional procurement of costs, among others those of disposal. It is interesting to observe that light polyethylene sachets now and later on obtained best results

23.

Similar early LCAs were conducted by Ian Boustead in the UK

24and Gustav Sundström in Sweden

25. Also Swiss studies

26date back to the 1970s. They were conducted at the EMPA in St. Gallen, see memories of Paul Fink, former director of the EMPA

27.

1.2.2

Environmental Background

Why did the development of LCA start in the 1970s? At least two reasons can be determined:

18 Quoted by Suter et al. 1995

19 Hunt and Franklin 1996

20 Klöpffer 2006

21 ISO 1997

22 Oberbacher et al. 1996

23 Schmitz et al. 1995

24 Boustead 1996

25 Lundholm and Sundström 1985, 1986

26 BUS 1984

27 Fink 1997

1. Rising problems of waste (therefore studies on packing)

2. Short-cuts in energy supply, acknowledgement of limited resources While the former issue was introduced into a just emerging politics of the environment, public awareness for the latter was raised by the bestseller

“Limits to Growth” and the report to the Club of Rome

28. Something must have been in the air because the book caused a sensation in the year of its publication 1972. To date one refers to a change of paradigm taking place:

throw away mentality of post war generation was suddenly under scrutiny.

Theory was confirmed by reality by the first oil crises in 1973. Estimations in the study concerning the time for exhaustion of resources had been too rigid, in this respect it was over-pessimistic, it however demonstrates the vulnerability of an industrial society which to a great extend relies on crude oil. To date, nothing has changed, on the contrary.

System analysis, well known by specialists for some time since, has had its breakthrough as a commonly accepted method. The International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA) at Laxenburg, Vienna, was founded.

In Germany, there have been car-free Sundays to which everyone adhered, and a spirit of optimism, to date unimaginable, a plethora of ideas on how alternative as well as common resources of energy could be used more efficiently. Some of them were realized, but most of them not (yet).

1.2.3

Energy Analysis

On this background it is not surprising that initially an energy analysis or process chain analysis theoretically evolved as an important contribution to life cycle analysis

29(see Chapter 3). In Germany this development was mainly promoted by Professor Schäfer at Technical University in Munich

30but also in industry

31. A (primary) energy demand summarized through all steps of the life cycle was formerly named “equivalent energy value”.

Recently the expression cumulated energy demand (CED)

32prevails.

By way of political solutions to the oil crisis in the 1980s an interest in LCA and its precursors declined to experience a totally unexpected upraise at the end of the decade.

28 Meadows et al: 1972, 1973

29 Mauch and Schäfer 1996

30 Mauch and Schäfer 1996; Eyrer 1996

31 Kindler and Nikles 1978, 1979

32 VDI 1997

1.2.4

The 1980s

Studies on LCA were sparse in the first half of the 1980s. An exception form the study of BUS, later Federal Agency for Environment, Forestry and Agriculture, Bern

33, which has already been named, a thesis by Marina Franke at TU Berlin

34and the development of product line analysis (PLA) by the Ökoinstitut

35. PLA supersedes LCA as it includes an analysis on demand (DA), social (SA) and economical aspects (EA):

PLA = BA + LCA + SA + EA

It therefore comprises all three concepts of sustainability according to the Brundlandt-Commission

36(see Chapter 6) and Agenda 21

37which passed legislation at UNO World Conference in Rio de Janeiro, 1992.

1.2.5

The SETAC

38Contribution

A strong upraise of interest in LCA in Europe and North America -where the designation life cycle analysis and assessment originated- was met by two international conferences as a starting point for a new development.

In 1990 a workshop was organized by Society of Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry (SETAC) in Smugglers Notch39 on A

Technical Framework for Life Cycle Assessment. One month later a European workshop took place on the same topic in Leuven

39.

In Smugglers Notch a famous LCA triangle was conceptualized, later persiflaged as “holy triangle” (Fig.1.2). From 1990 to 1993 SETAC and SETAC Europe were leading agents in the development, harmonization and standardization of LCA. Their reports

40concerning the development of the methodology were only superseded by German “Ecobalance of

33 BUS 1984

34 Franke 1984

35 Projektgruppe Ökologische Wirtschaft 1987

36 World Commission on Environment and Development 1987

37 Agenda 21: UNO 1982

38 Klöpffer 2006

39 Leuven 1990

40 SETAC 1991, 1993; SETAC Europe 1992; Fava et al. 1993,1994

Packings 1990”

41, updated in 1996 and 1998

42. The UBA study in 1992 also had great influence

43. A French adoption of history and methodology,

“L'Ecobilan”, was published

44.

Special contributions from the Centre of Environment of University Leiden (CML) under the leadership of Professor Helias de Haes were appreciated in a socio-economic study by Gabathuler

45and in a special issue of the International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment

46. Greatest achievement of CML was without doubt a stronger focus on ecological aspects of LCA compared to previously more technical ones. Nevertheless, a prior Swiss LCA had already featured a simple method of impact

analysis

47. In practice, the CML method tended to overstress chemical releases in the impact analysis, at the same time due to an absence of generally adhered indicators an overuse of natural resources such as minerals, fossils, biology and land was shielded

48(see Chapter 4).

1.3

Structure of LCA 1.3.1

Structure according to SETAC

A first attempt to introduce a structure into LCA was the SETAC triangle of 1990/91 already quoted.

<<Fig. 1.2>>

Fig. 1.2 The SETAC-triangle in LCA guidelines (“Code of Practice”)

49The original components of SETAC 1990/91 were adapted by the UBA

50Berlin in 1992 as

41 BUWAL 1991

42 BUWAL 1996, 1998

43 UBA 1992

44 Blouet and Rivoire 1995

45 Gabathuler 1998

46 Huijbregts et al. 2006

47 BUS 1984

48 Klöpffer and Renner 2003

49 SETAC 1993

50 UBA 1992

- LCA, Inventory - Impact Analysis

- Improvement Analysis

Here LCA, formerly called inventory, means material and energy analysis of the examined system from cradle-to-grave. The resulting inventory table contains a list of all inputs and outputs (see Fig. 1.3 and Chapter 3).

“Bare numbers” of LCA need an ecological analysis or weighting, inputs and outputs will be sorted corresponding to their impact to the

environment. Thus for instance all releases into the air causing acid rain will be aggregated (see chapter 4). This procedure was formerly called Impact Analysis, later Impact Assessment.

<<Fig. 1.3>>

Fig. 1.3 Analysis of matter and energy of a product system

A valuation of the data procured in LCA was postulated in Smugglers Notch. It was called Improvement Analysis, later renamed Improvement Assessment. Introduction of this component was regarded as great progress, because the interpretation of the data was conducted according to specific rules. The Environmental Agency Berlin

51has included this task in its recommendation to the conduct of LCAs in 1992 as an option. The rules for interpretation were later modified during the standardization process of ISO (see section 1.3.2). To date this component is known by valuation

52(see Fig. 1.4).

1.3.2

Structure of LCA according to ISO

Up to now the structure developed by SETAC has essentially been

maintained by ISO

53with the exception of Improvement Assessment which was replaced by “interpretation” (valuation). An optimization of product

51German: Umwelbundesamt (UBA)

52 ISO 1997

53 ISO 1997, 2006a

systems was not adapted as standard content by ISO, but was listed besides other applications of the standard. The structure of the international

standard is depicted in Fig. 1.4.

<<Fig. 1.4>>

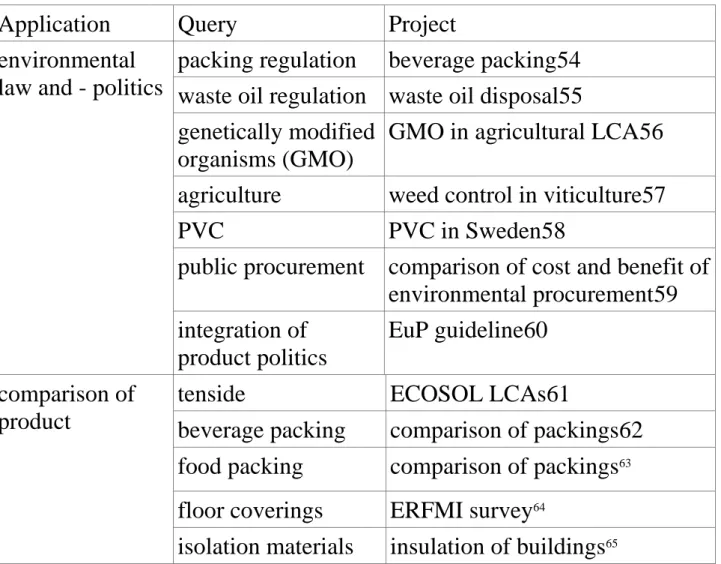

Fig. 1.4 LCA Phases according to ISO EN 14040:1997/2006 Tab. 1.1 Examples of LCA applications according to ISO 140.

Application Query Project

environmental law and - politics

packing regulation beverage packing54 waste oil regulation waste oil disposal55 genetically modified

organisms (GMO)

GMO in agricultural LCA56 agriculture weed control in viticulture57

PVC PVC in Sweden58

public procurement comparison of cost and benefit of environmental procurement59 integration of

product politics

EuP guideline60 comparison of

product

tenside ECOSOL LCAs61

beverage packing comparison of packings62 food packing comparison of packings

63floor coverings ERFMI survey

64isolation materials insulation of buildings

6554Schmitz et al. 1995; UBA 2000, 2002

55UBA 2000a

56Klöpffer et al. 1999

57IFEU/SLFA 1998

58 Tukker et al. 1996

59Rüdenauer et al. 2007

60Kemma et al. 2005

61Stalmans et al. 1995; Janzen 1995

62IFEU 2002, 2004, 2006, 2007

63IFEU 2006a; Humbert et al. 2008

64Günther and Lambowski 1997, 1998

65Schmidt et al. 2004

communication consumer consultation ISO type III declaration

66chain management PCR

67: electricity, steam,

water

68ecological building EPD

69: building products

70carbon footprinting PCR: climatic product

declaration

71carbon-neutral enterprise

72waste

management

concepts of disposal graphic papers

73recycling plastics

74enterprise ecological valuation of business lines

environmental achievement of an enterprise

75Components of LCA have been renamed and the following are now mandatory in Germany:

- Definition of Goal and Scope - Life Cycle Inventory

- Impact Assessment - Valuation

The arrows in Fig 1.4 allow an iterative approach that is often necessary (see Chapter 2). Direct applications of an LCA lie out of scope of standardized components of an LCA.

This makes sense because besides foreseeable applications during the standardization process, others exist in real life and have been summarized as “miscellaneous applications”. Examples can be found in Table 1.1.

1.3.3

Valuation – A Separate Component?

66Schmincke and Grahl 2006

67Product Category Rules

68Vattenfall et al. 2007

69Environmental Product Declaration

70Deutsches Institut für Bauen und Umwelt 2007

71Svenska Miljösttyrningsrådet 2006; BSI 2008

72Gensch 2008

73Tiedemann 2000

74Heye and Kremer 1999

75Wright et al. 1997

Special fate is attached to the component valuation which has not been assigned as standard. A valuation will always be necessary if the results of a comparative LCA are not straightforward. A trade-off of system A

against system B needs to be made if the former has lower energy

consumption, but on the other hand has releases of substances leading to water eutrophication and to the emergence of ozone near the surface: What will be of greater importance? For these decisions, subjective or standard notions of value are necessary, common in daily life e.g. during purchase decisions

76. For this reason a valuation based on exclusively scientific methods cannot be made.

Because of this, it was proposed by SETAC Europe at Leiden 1991

77to introduce valuation as a component of its own. This proposition was

seized by UBA Berlin

78and by DIN NAGUS

79later on. But as subjective notions of value cannot be standardized, a methodology was developed to support the process of conclusion. In SETAC “Code of Practice”

80these regulations were subordinated to the component impact assessment.

However, no changes were made by the standardization process of ISO:

regulations are integrated into the component impact assessment

81(see section 4.3). The final survey of results which leads to a conclusion

82is supposed to take place in the final component “valuation“

83of an LCA (see Chapter 5).

The discussion on valuation has during the final years of the 1990s increased to such an extent that former Minister of the Environment

Angela Merkel

84joined the discussion. As consequence, the association of the German Industry (BDI) published a policy brief

85and the UBA Berlin then elaborated an ISO-conformal valuation methodology

86.

1.4

Standardization of LCA

76DIN-NAGUS 1994; Giegrich et al. 1995; Klöpffer and Volkwein 1995; Neitzel 1996

77SETAC Europe 1992

78UBA 1994

79DIN NAGUS 1994; Neitzel 1996

80SETAC 1993

81ISO 2000a

82Grahl and Schmincke 1996

83ISO 2000b

84Merkel 1997

85BDI 1999

86SCHMITZ AND PAULINI 1999

1.4.1

Process of Formation

LCA standards ISO 14040 and 14044 belong to the ISO 14000 group concerning environmental management (Fig. 1.5).

The committee responsible of DIN in Germany is the NAGUS

87. National propositions are brought together in the Technical Committee 207 (TC 207) at the International Standards Organization ISO at international level, with a participation of all nations which are members of the TC 207 by their standardizations organizations, and international standards are developed.

Generally this process takes a couple of years.

LCA standardization by national standardization organizations

88and

above all by ISO has been conducted since the beginning of the 1990s with great effort

89. This was difficult to achieve because individual components of LCA were still under development. On a national level, only two

standardization organizations have developed their own LCA

standardization before ratification of ISO 14040: AFNOR (France) and CSA (Canada). To date, a singular internationally acceptable

standardization is aimed at to promote international communication and this is why France and Canada have stepped into the ISO process.

<<Fig. 1.5>>

Fig. 1.5 ISO 14000 Model

90The most important standardization activity for LCA is therefore

conducted by ISO. European Standardizations (CEN) and their subsequent national organizations adapt ISO regulations into languages (CEN 14040 standards are available in three official languages, English, French and German). DIN-NAGUS and similar national committees activity is

focused on legwork for the ISO council, the work-out and harmonization of supplementary comments, a translation of ISO texts and on

supplementary standardization for specifically German or national issues.

The first series of the international LCA standards abutted on the structure of Fig 1.4:

- ISO 14040 LCA – Principles and general demands; international standard 1997

87Normenausschuss Grundlagen des Umweltschutzes i.e. Environmental Standardisation Organisation

88 e.g.: CSA 1992; DIN-NAGUS 1994; AFNOR 1994

89ISO1997,1998,2000A,2000B;MARSMANN 1997;SAUR 1997;KLÜPPEL 1997,2002

90 Normenausschuss Grundlagen des Umweltschutzes (NAGUS) in DIN Deutsches Institut für Normung e. V. 2008.

- ISO 14041: LCA – Definition of goal and scope as well as LCI;

international standard 1998

- ISO 14042: LCA – Impact assessment; international standard 2000;

- ISO 14043: LCA – Valuation; international standard 2000.

1.4.2

Status Quo

A review of International Standards in 2001-2006 led to restructuring without any essential changes

91. The standard continues to be called ISO 14040

92with no mandatory directives. Directives have been summarised in a new standard ISO 14044

93comprising all LCA elements in Fig.1.4.

Two technical reports (TR) and one technical specification has been added, which are only available in English:

- ISO/TR 14047 Illustrative example on how to apply ISO 140042 - ISO/TS 14048 Data documentation format

- ISO/TR 14049 Examples of the application of ISO 14041 to goal and scope definition and inventory analysis

These are non-mandatory documents meant for help and support.

As many as 24 national standardization organizations participated in a first round of ISO standardization talks. The final vote led to an overall

acceptance of 95%. LCA is therefore the only internationally accepted standardized method for an analysis of environmental aspects and potential impact of product systems. The standards are verified on a five year basis. Revision of 2006 will therefore be valid until 2011.

Chapter 5 will focus on objective content of individual components of LCA, their advantages and disadvantages.

1.5

Literature and Information on LCA

Until the mid of the 1990s only “gray” LCA literature was available.

Meanwhile, a couple of books mostly in English have been published

94.

91Finkbeiner et al. 2006

92ISO 2006A

93ISO 2006B

94 Schmidt and Schorb 1995; Curran 1996; Eyrer 1996; Fullana and Puig 1997; Wenzel et al. 1997; Hauschild and

Papers from national and international organizations provide essential information to LCA, mostly SETAC and SETAC Europe

95, The Nordic Council

96, US EPA

97, UBA Berlin

98, BUS/BUWAL Bern

99and the European Environment Agency Copenhagen (EEA)

100.

Since 1996 “The International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment” (Int. J.

LCA) is published at ecomed publishing Landsberg/Lech and Heidelberg (since 1.1.2008 at Springer, Heidelberg). Queries on current information on this journal and similar publications can be made by the internet

101. The journal has recently developed into a leading publication organ of the promotion of the LCA methodology, supplemented by the series “LCA Documents” of Ecoinforma Press, (since 2008 part of Wiley-Blackwell), Bayreuth, in cooperation with ecomed. The Int. J. LCA is also available electronically and short cuts, editorials and similar publications can be downloaded. Further journals with regular contributions to LCA are the Journal of Industrial Ecology (MIT Press, part of Wiley-Blackwell since 2008), Cleaner Production (Elsevier) and Integrated Environmental Assessment and Management, IEAM (SETAC Press).

Other specialized journals also publish LCA literature. In 1995 for instance, an ECOSOL-Tenside-LCA of the European tenside producers was conducted by Franklin Associates, comprising two booklets, titled

“Tenside, Surfactants, and Detergents”

102.

The significance of publication for propagation and discussion of methods, theories and results of research cannot be over-evaluated. Especially

within new branches of science, peer reviews judge on a day-to-day basis upon scientific validity

103. They serve as veneer for the big principles of epistemology with special focus according to Popper on falsifiability

104which for LCA cannot be examined unambiguously. Individual LCA components will undergo a critical review.

Wenzel 1998; Badino and Baldo 1998; Guinée et al. 2002; Baumann and Tillman 2004

95SETAC 1991, 1993; SETAC Europe 1992; Fava et al. 1993, 1994; Huppes and Schneider 1994;

UDO DE HAES 1996; UDO DE HAES ET AL. 2002

96Lindfors et al. 1994,1994b, 1995

97EPA 1993, 2006

98UBA 1992, 1997; Klöpffer and Renner 1995; Schmitz and Paulini 1999

99BUS 1984; BUWAL 1990, 1991, 1996, 1998

100Jensen et al. 1997

101http://www.scientificjournals.com/lca

102Janzen 1995; Klöpffer et al. 1995; Berna et al. 1995; Stalmans et al. 1995; Hirsinger and Schlick

1995A, 1995B, 1995C, 1995D; THOMAS 1995; BERENBOLD AND KOSSWIG 1995; POSTLETHWAITE 1995A, 1995B; SCHUL ET AL. 1995; FRANKE ET AL. 1995

103Klöpffer 2007

104Popper 1934

1.6

References ((NICHT übersetzt))

AFNOR 1994: Association Française de Normalisation (AFNOR): Analyse de cycle de vie. Norme NF X 30–300. 3/1994.

Badino und Baldo 1998: Badino, V.; Baldo, G. L.: LCA – Istruzioni per l’uso. Progetto Leonardo, Esculapio Editore, Bologna.

Baumann und Tillman 2004: Baumann, H.; Tillman, A.-M.: The Hitch Hiker’s Guide to LCA. An Orientation in LCA Methodology and Application. Studentlitteratur, Lund. ISBN 91-44-02364-2.

BDI 1999: Bundesverband der Deutschen Industrie e. V. (BDI): Die Durchführung von Ökobilanzen zur Information von Öffentlichkeit und Politik. BDI-Drucksache Nr. 313. Verlag Industrie-Förderung, Köln, April 1999. ISSN 0407-8977.

Beck 1993: Beck, M. (Hrsg.): Ökobilanzierung im betrieblichen Management. Vogel Buchverlag, Würzburg. ISBN 3-8023-1479-4.

Berenbold und Kosswig 1995: Berenbold, H.; Kosswig, K.: A life-cycle inventory for the production of secondary alkane sulphonates (SAS) in Europe. Tenside Surf. Det. 32, 152–156.

Berna et al. 1995: Berna, J. L.; Cavalli, L.; Renta, C.: A lifecycle inventory for the production of linear akylbenzene sulphonates in Europe. Tenside Surf. Det. 32, 122–127.

BIfA/IFEU/Flo-Pak 2002: Kunststoffe aus nachwachsenden Rohstoffen: Vergleichende Ökobilanz für Loose-fill-Packmittel aus Stärke bzw. aus Polystyrol. Bayerisches Institut für angewandte Umweltforschung und -technik, Augsburg.

Blouet und Rivoire 1995: Blouet, A.; Rivoire, E.: L’Écobilan. Les produits et leurs impacts sur l’environnement. Dunod, Paris. ISBN 2-10-002126-5.

Boustead 1996: Boustead, I.: LCA – How it came about. The beginning in UK. Int. J. LCA 1 (3), 147–150.

Boustead und Hancock 1979: Boustead, I.; Hancock, G. F.: Handbook of Industrial Energy Analysis. Ellis Horwood Ltd., Chichester.

Braunschweig und Müller-Wenk 1993: Braunschweig, A.; Müller-Wenk, R.: Ökobilanzen für Unternehmungen. Eine Wegleitung für die Praxis. Verlag Haupt, Bern.

BSI 2008: British Standards Institution (Ed.): Publicly Available Specification (PAS) 2050:2008.

Specification for the assessment of the life cycle greenhouse gas emissions of goods and services.

BUS 1984: Bundesamt für Umweltschutz (BUS), Bern (Hrsg.): Oekobilanzen von Packstoffen.

Schriftenreihe Umweltschutz, Nr. 24. Bern, April 1984.

BUWAL 1990: Ahbe, S.; Braunschweig, A.; Müller-Wenk, R.: Methodik für Oekobilanzen auf der Basis ökologischer Optimierung. In: Bundesamt für Umwelt, Wald und Landschaft (BUWAL), Bern (Hrsg.): Schriftenreihe Umwelt Nr. 133.

BUWAL 1991: Habersatter, K.; Widmer, F.: Oekobilanzen von Packstoffen. Stand 1990. In: Bundesamt für Umwelt, Wald und Landschaft (BUWAL), Bern (Hrsg.): Schriftenreihe Umwelt Nr. 132, Februar 1991.

BUWAL 1996,1998: Habersatter, K.; Fecker, I.; Dall’Aqua, S.; Fawer, M.; Fallscher, F.; Förster, R.;

Maillefer, C.; Ménard, M.; Reusser, L.; Som, C.; Stahel, U.; Zimmermann, P.: Ökoinventare für Verpackungen. ETH Zürich und EMPA St. Gallen für BUWAL und SVI, Bern. In: Bundesamt für Umwelt, Wald und Landschaft (Hrsg.): Schriftenreihe Umwelt Nr. 250/Bd. I und II. 2. erweiterte und aktualisierte Auflage, Bern 1998 (1. Auflage 1996).

CSA 1992: Canadian Standards Association (CSA): Environmental Life Cycle Assessment.

CAN/CSA-Z760. 5th Draft Edition, May 1992.

Curran 1996: Curran, M. A. (ed.): Environmental Life- Cycle Assessment. McGraw-Hill, New York. ISBN 0-07-015063-X.

Deutsches Institut für Bauen und Umwelt 2007: TECU® – Kupferbänder und Kupferlegierungen. KME Germany AG. Programmhalter: Deutsches Institut für Bauen und Umwelt. Registrierungsnummer No: AUB-KME-30807-D. Ausstellungsdatum: 2007-11-01; verifiziert von: Dr. Eva Schmincke.

DIN-NAGUS 1994: DIN-NAGUS: Grundsätze produktbezogener Ökobilanzen (Stand Oktober 1993).

DIN-Mitteilungen 73 (3), 208–212.

EPA 1993: Vigon, B. W.; Tolle, D. A.; Cornaby, B. W.; Latham, H. C.; Harrison, C. L.; Boguski, T. L.;

Hunt, R. G.; Sellers, J. D.: Life Cycle Assessment: Inventory Guidelines and Principles.

EPA/600/R-92/245, Office of Research and Development. Cincinnati, Ohio.

EPA 2006: Scientific Applications International Corporation (SAIC): Life Cycle Assessment: Principles and Practice. U.S. EPA, Systems Analysis Branch, National Risk Management Research

Laboratory. Cincinnati, Ohio.

Eyrer 1996: Eyrer, P. (Hrsg.): Ganzheitliche Bilanzierung. Werkzeug zum Planen und Wirtschaften in Kreisläufen. Springer, Berlin 1996. ISBN 3-540-59356-X.

Fava et al. 1993: Fava, J.; Consoli, F. J.; Denison, R.; Dickson, K.; Mohin, T.; Vigon, B. (eds.): Conceptual Framework for Life-Cycle Impact Analysis. Workshop Report. SETAC and SETAC Foundation for Environ. Education. Sandestin, Florida, February 1–7, 1992. Published by SETAC.

Fava et al. 1994: Fava, J.; Jensen, A. A.; Lindfors, L.; Pomper, S.; De Smet, B.; Warren, J.; Vigon, B.

(eds.): Conceptual Framework for Life-Cycle Data Quality. Workshop Report. SETAC and SETAC Foundation for Environ. Education. Wintergreen, Virginia, October 1992. Published by SETAC June 1994.

Fink 1997: Fink, P.: LCA – How it came about. The roots of LCA in Switzerland: Continuous learning by doing. Int. J. LCA 2 (3), 131–134.

Finkbeiner et al. 2006: Finkbeiner, M.; Inaba, A.; Tan, R. B. H.; Christiansen, K.; Klüppel, H.-J.: The new international standards for life cycle assessment: ISO 14040 and ISO 14044. Int. J. LCA 11 (2), 80–85.

Fleischer und Schmidt 1995: Fleischer, G.; Schmidt, W.-P.: Life Cycle Assessment. Ullmanns Encyclopaedia of Industrial Chemistry, Vol. B8, 585–600.

Fleischer und Schmidt 1996: Fleischer, G.; Schmidt, W.-P.: Functional unit for systems using natural raw materials. Int. J. LCA 1 (1), 23–27.

Franke 1984: Franke, M.: Umweltauswirkungen durch Getränkeverpackungen. Systematik zur Ermittlung der Umweltauswirkungen von komplexen Prozessen am Beispiel von Einweg- und

Mehrweg-Getränkebehältern. EF-Verlag für Energie- und Umwelttechnik, Berlin.

Franke et al. 1995: Franke, M.; Berna, J. L.; Cavalli, L.; Renta, C.; Stalmans, M.; Thomas, H.: A life-cycle inventory for the production of petrochemical intermediates in Europe. Tenside Surf. Det. 32, 384–396.

Fullana und Puig 1997: Fullana, P.; Puig, R.: Análisis del ciclo de vida. Primera edición. Rubes Editorial, S.L., Barcelona. ISBN 84-497-0070-1.

Gabathuler 1998: Gabathuler, H.: The CML story. How environmental sciences entered the debate on LCA. Int. J. LCA 2 (4), 187–194.

Gensch 2008: Gensch, C.-O.; Klimaneutrale Weleda AG. Endbericht, Öko-Institut Freiburg.

Giegrich et al. 1995: Giegrich, J.; Mampel, U.; Duscha, M.; Zazcyk, R.; Osorio-Peters, S.; Schmidt, T.:

Bilanzbewertung in produktbezogenen Ökobilanzen. Evaluation von Bewertungsmethoden,

Perspektiven. Endbericht des Instituts für Energie- und Umweltforschung Heidelberg GmbH (IFEU) an das Umweltbundesamt, Berlin. Heidelberg, März 1995. UBA Texte 23/95. Berlin. ISSN

0722-186X.

Grahl und Schmincke 1996: Grahl, B.; Schmincke, E.: Evaluation and decision-making processes in life cycle assessment. Int. J. LCA 1 (1), 32–35.

Günther und Langowski 1997: Günther, A.; Langowski, H.-C.: Life cycle assessment study on resilient floor coverings. Int. J. LCA 2(2), 73–80.

Günther und Langowski 1998: Günther, A.; Langowski, H.-C. (eds.): Life Cycle Assessment Study on Resilient Floor Coverings. For ERFMI (European Resilient Flooring Manufacturers Institute).

Fraunhofer IRB Verlag 1998. ISBN 3-8167-5210-1.

Guinée et al. 2002: Guinée, J. B. (final editor); Gorée, M.; Heijungs, R.; Huppes, G.; Kleijn, R.; Koning, A.

de; Oers, L. van; Wegener Sleeswijk, A.; Suh, S.; Udo de Haes, H. A.; Bruijn, H. de; Duin, R. van;

Huijbregts, M. A. J.: Handbook on Life Cycle Assessment – Operational Guide to the ISO Standards. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht. ISBN 1-4020-0228-9.

Hauschild und Wenzel 1998: Hauschild, M.; Wenzel, H.: Environmental Assessment of Products Vol. 2:

Scientific Background. Chapman & Hall, London. ISBN 0-412-80810-2.

Heijungs 1997: Heijungs, R.: Economic Drama and the Environmental Stage. Formal Derivation of Algorithmic Tools for Environmental Analysis and Decision-Support from a Unified

Epistemological Principle. Proefschrift (Dissertation/PhD-Thesis). Leiden. ISBN 90-9010784-3.

Heijungs und Suh 2002: Heijungs, R.; Suh, S.: The Computational Structure of Life Cycle Assessment.

Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht 2002. ISBN 1-4020-0672-1.

Heyde und Kremer 1999: Heyde, M.; Kremer, M.: Recycling and Recovery of Plastics from Packaging in Domestic Waste. LCA-type Analysis of Different Strategies. LCA Documents Vol. 5. Ecoinforma Press, Bayreuth. ISBN 3-928379-57-7.

Hirsinger und Schlick 1995a: Hirsinger, F.; Schlick, K.-P.: A life-cycle inventory for the production of alcohol sulphates in Europe. Tenside Surf. Det. 32, 128–139.

Hirsinger und Schlick 1995b: Hirsinger, F.; Schlick, K.-P.: A life-cycle inventory for the production of alkyl polyglucosides in Europe. Tenside Surf. Det. 32, 193–200.

Hirsinger und Schlick 1995c: Hirsinger, F.; Schlick, K.-P.: A life-cycle inventory for the production of detergentgrade alcohols. Tenside Surf. Det. 32, 398–410.

Hirsinger und Schlick 1995d: Hirsinger, F.; Schlick, K.-P.: A life-cycle inventory for the production of oleochemical raw materials. Tenside Surf. Det. 32, 420–432.

Huijbregts et al. 2006: Huijbregts, M. A. J.; Guinée, J. B.; Huppes, G.; Potting, J. (eds.): Special issue honoring Helias A. Udo de Haes at the occasion of his retirement. Special Issue 1, Int. J. LCA 11, 1–132.

Humbert et al. 2008: Humbert, S.; Rossi, V.; Margni, M.; Jolliet, O.; Loerincik, Y: Life cycle assessment of two baby food packaging alternatives: glass jars vs. plastic pots. Int. J. LCA (in press).

Hunt und Franklin 1996: Hunt, R.; Franklin, W. E.: LCA – How it came about. Personal reflections on the origin and the development of LCA in the USA. Int. J. LCA 1 (1), 4–7.

Huppes und Schneider 1994: Huppes, G.; Schneider, F. (eds.): Proceedings of the European Workshop on Allocation in LCA. Leiden, February 1994. SETAC Europe, Brussels.

IFEU/SLFA 1998: Ökobilanz Beikrautbekämpfung im Weinbau. Im Auftrag des Ministeriums für Wirtschaft, Verkehr, Landwirtschaft und Weinbau Rheinland-Pfalz, Mainz. IFEU, Heidelberg, SLFA, Neustadt an der Weinstraße, Dezember 1998.

IFEU 2002: Ostermayer, A.; Schorb, A.: Ökobilanz Fruchtsaftgetränke Verbund-Standbodenbeutel 0,2 l, MW-Glasflasche, Karton Giebelpackung. Im Auftrag der Deutschen SISI-Werke, Eppelheim. IFEU Heidelberg, Juli 2002.

IFEU 2004: Detzel, A.; Giegrich, J.; Krüger, M.; Möhler, S.; Ostermayer, A. (IFEU): Ökobilanz PET-Einwegverpackungen und sekundäre Verwertungsprodukte. Im Auftrag von PETCORE, Brüssel. IFEU Heidelberg, August 2004.

IFEU 2006: Detzel, A.; Böß, A.: Ökobilanzieller Vergleich von Getränkekartons und PETEinwegflaschen.

Endbericht, Institut für Energie- und Umweltforschung (IFEU) Heidelberg an den Fachverband Kartonverpackungen (FKN) Wiesbaden, August 2006.

IFEU 2006a: Detzel, A.; Krüger, M. (IFEU): LCA for food contact packaging made from PLA and traditional materials. On behalf of Natureworks LLC. IFEU Heidelberg, Juli 2006.

IFEU 2007: Krüger, M.; Detzel, A. (IFEU): Aktuelle Ökobilanz zur 1,5-L-PET-Einwegflasche in Österreich unter Einbeziehung des Bottle-to- Bottle-Recycling. Im Auftrag des Verbands der Getränkehersteller Österreichs. IFEU Heidelberg, Oktober 2007.

ISO 1997: International Standard (ISO); Norme Européenne (CEN): Environmental management – Life cycle assessment – Principles and framework. Prinzipien und allgemeine Anforderungen. EN ISO 14040 Juni 1997.

ISO 1998: International Standard (ISO); Norme Euro péenne (CEN): Environmental management – Life cycle assessment: Goal and scope definition and inventory analysis (Festlegung des Ziels und des Untersuchungsrahmens sowie Sachbilanz) ISO EN 14041 (1998).

ISO 2000a: International Standard (ISO); Norme Euro péenne (CEN): Environmental management – Life cycle assessment: Life cycle impact assessment (Wirkungsabschätzung). International Standard ISO EN 14042.

ISO 2000b: International Standard (ISO); Norme Européenne (CEN): Environmental manage ment – Life cycle assessment: Inter pretation (Auswertung). International Standard ISO EN 14043.

ISO 2006a: ISO TC 207/SC 5: Environmental management – Life cycle assessment – Principles and framework. ISO EN 14040 2006-10.

ISO 2006b: ISO TC 207/SC 5: Environmental manage ment – Life cycle assessment – Requirements and guidelines. ISO EN 14044 2006-10.

Janzen 1995: Janzen, D. C.: Methodology of the European surfactant life-cycle inventory for detergent surfactants production. Tenside Surf. Det. 32, 110–121.

Jensen et al. 1997: Jensen, A. A.; Hoffman, L.; Møller, B. T.; Schmidt, A.; Christiansen, K.; Elkington, J.;

van Dijk, F.: Life Cycle Assessment (LCA). A guide to approaches, experiences and information sources. European Environmental Agency. Environmental Issues Series No. 6, August 1997.

Kemna et al. 2005: Kemna, R.; van Elburg, M.; Li, W.; van Holsteijn, R.: Methodology Study Eco-design of Energy-using Products – MEEUP Methodology Report for DG ENETR, Unit ENTR/G/3 in collaboration with DG TREN, Unit D1. Delft, 2005.

Kindler und Nikles 1979: Kindler, H.; Nikles, A.: Energieaufwand zur Herstellung von Werkstoffen – Berechnungsgrundsätze und Energieäquivalenzwerte von Kunststoffen. Kunststoffe 70, 802–807.

Kindler und Nikles 1980: Kindler, H.; Nikles, A.: Energiebedarf bei der Herstellung und Verarbeitung von Kunststoffen. Chem.-Ing.-Tech. 51, 1–3.

Klöpffer 1994: Klöpffer, W.: Environmental hazard assess ment of chemicals and products. Part IV. Life cycle assessment. ESPR – Environ. Sci. & Pollut. Res. 1 (5), 272–279.

Klöpffer 1997: Klöpffer, W.: Life cycle assessment – From the beginning to the current state.

ESPREnviron. Sci. & Pollut. Res. 4 (4), 223–228.

Klöpffer 2003: Klöpffer, W.: Life-cycle based methods for sustainable product development. Editorial for the LCM Section in Int. J. LCA 8 (3), 157–159.

Klöpffer 2006: Klöpffer, W.: The Role of SETAC in the development of LCA. Int. J. LCA Special Issue 1, Vol. 11, 116–122.

Klöpffer 2007: Klöpffer, W.: Publishing scientific articles with special reference to LCA and related topics.

Int. J. LCA 12 (2), 71–76.

Klöpffer 2008: Klöpffer, W.: Life-cycle based sustainability assessment of products. Int. J. LCA 13 (2), 89–94.

Klöpffer et al. 1995: Klöpffer, W.; Grießhammer, R.; Sundström, G.: Overview of the scientific peer review of the European life cycle inventory for surfactant production. Tenside Surf. Det. 32, 378–383.

Klöpffer und Renner 1995: Klöpffer, W.; Renner, I.: Methodik der Wirkungsbilanz im Rahmen von Produkt-Ökobilanzen unter Berücksichtigung nicht oder nur schwer quantifizierbarer

Umwelt-Kategorien. Bericht der C.A.U. GmbH, Dreieich, an das Umweltbundesamt (UBA), Berlin.

UBA-Texte 23/95, Berlin. ISSN 0722-186X.

Klöpffer und Volkwein 1995: Klöpffer, W.; Volkwein, S.: Bilanzbewertung im Rahmen der Ökobilanz.

Kapitel 6.4 in Thomé-Kozmiensky, K. J. (Hrsg.): Enzyklopädie der Kreislaufwirtschaft, Management der Kreislaufwirtschaft. EF-Verlag für Energie- und Umwelttechnik, Berlin, S.

336–340.

Klöpffer et al. 1999: Klöpffer, W.; Renner, I.; Tappeser, B.; Eckelkamp, C.; Dietrich, R.: Life Cycle Assessment gentechnisch veränderter Produkte als Basis für eine umfassende Beurteilung

möglicher Umweltauswirkungen. Federal Environment Agency Ltd. Monographien Bd. 111, Wien.

ISBN 3-85457-475-4.

Klüppel 1997: Klüppel, H.-J.: Goal and scope definition and life cycle inventory analysis. Int. J. LCA 2 (1), 5–8. Leuven 1990: Life Cycle Analysis for Packaging Environmental Assessment. Proceedings of the Specialised Workshop organized by Procter & Gamble, Leuven, Belgium, September 24/25.

Lindfors et al. 1994a: Lindfors, L.-G.; Christiansen, K.; Hoffmann, L.; Virtanen, Y.; Juntilla, V.; Leskinen, A.; Hansen, O.-J.; Rønning, A.; Ekvall,T.; Finnveden, G.; Weidema, Bo P.; Ersbøll, A. K.; Bomann, B.; Ek, M.: LCA-NORDIC Technical Reports No. 10 and Special Reports No. 1–2. Tema Nord 1995:503. Nordic Council of Ministers. Copenhagen 1994. ISBN 92-9120-609-1.

Lindfors et al. 1994b: Lindfors, L.-G.; Christiansen, K.; Hoffmann, L.; Virtanen, Y.; Juntilla, V.; Leskinen, A.; Hansen, O.-J.; Rønning, A.; Ekvall,T.; Finnveden, G.: LCA-NORDIC Technical Reports No.

1–9. Tema Nord 1995:502. Nordic Council of Ministers. Copenhagen 1994.

Lindfors et al. 1995: Lindfors, L.-G.; Christiansen, K.; Hoffmann, L.; Virtanen, Y.; Juntilla, V.; Hanssen, O.-J.; Rønning, A.; Ekvall, T.; Finnveden, G.: Nordic Guidelines on Life-Cycle Assessment. Nordic Council of Ministers. Nord 1995:20. Copenhagen 1995.

Lundholm und Sundström 1985: Lundholm, M. P.; Sundström, G.: Ressourcen und Umweltbeeinflussung.

Tetrabrik Aseptic Kartonpackungen sowie Pfandflaschen und Einwegflaschen aus Glas. Malmö 1985.

Lundholm und Sundström 1986: Lundholm, M. P.; Sundström, G.: Ressourcen- und Umweltbeeinflussung durch 1414vch01.indd 23 03.02.2009 16:04:17 24 1 Einleitung zwei Verpackungssysteme für Milch, Tetra Brik und Pfandflasche. Malmö 1986.

Marsmann 1997: Marsmann, M.: ISO 14040 – The first project. Int. J. LCA 2 (3), 122–123.

Mauch und Schäfer 1996: Mauch, W.; Schaefer, H.: Methodik zur Ermittlung des kumulierten

Energieaufwands. In Eyrer, P. (Hrsg.): Ganzheitliche Bilanzierung. Werkzeug zum Planen und Wirtschaften in Kreisläufen. Springer, Berlin, S. 152–180. ISBN 3-540-59356-X.

Meadows et al. 1972: Meadows, D. H.; Meadows, D. L.; Randers, J.; Behrens III, W. W.: The Limits to Growth. A Report for the Club of Rome’s Project on the Predicament of Mankind. Universe Books, New York 1972. ISBN 0-87663-165-0.

Meadows et al. 1973: Meadows, D. L.; Meadows, D. H.; Zahn, E.; Milling, P.: Die Grenzen des

Wachstums. Bericht des Club of Rome zur Lage der Menschheit. 101.–200. Ts. rororo Taschenbuch, Hamburg 1973; neue Auflage im dtv Taschenbuchverlag. ISBN 3-499-16825-1.

Merkel 1997: Merkel, A.: Foreword: ISO 14040. Int. J. LCA 2 (3), 121.

Neitzel 1996: Neitzel, H. (ed.): Principles of product-related life cycle assessment. Int. J. LCA 1 (1), 49–54.

O’Brien et al. 1996: O’Brien, M.; Doig, A.; Clift, R.: Social and environmental life cycle assessment (SELCA) approach and methodological development. Int. J. LCA 1 (4), 231–237.

Oberbacher et al. 1996: Oberbacher, B.; Nikodem, H.; Klöpffer, W.: LCA – How it came about. An early systems analysis of packaging for liquids which would be called an LCA today. Int. J. LCA 1 (2), 62–65.

Popper 1934: Popper, K. R.: Logik der Forschung. J. Springer, Wien 1934. 7. Auflage: J. C. B. Mohr (Paul Siebeck), Tübingen 1982. 1st English edition: The Logic of Scientific Discovery. Hutchison, London 1959.

Postlethwaite 1995a: Postlethwaite, D.: A life-cycle inventory for the production of sulphur and caustic soda in Europe. Tenside Surf. Det. 32, 412–418.

Postlethwaite 1995b: Postlethwaite, D.: A life-cycle inventory for the production of soap in Europe.

Tenside Surf. Det. 32, 157–170.

Projektgruppe ökologische Wirtschaft 1987: Produktlinienanalyse: Bedürfnisse, Produkte und ihre Folgen.

Kölner Volksblattverlag, Köln.

Rüdenauer et al. 2007: Rüdenauer, I.; Dross, M.; Eberle, U.; Gensch, C.; Graulich, K.; Hünecke, K.; Koch, Y.; Möller, M.; Quack, D.; Seebach, D.; Zimmer, W.; et al.: Costs and Benefits of Green Public Procurement in Europe. Part 1: Comparison of the Life Cycle Costs of Green and Non Green Products. Service contract number: DG ENV.G.2/SER/2006/0097r. Öko-Institut Freiburg 2007.

Saur 1997: Saur, K.: Life cycle impact assessment (LCA-ISO activities). Int. J. LCA 2 (2), 66–70.

Schaltegger 1996: Schaltegger, S. (Ed.): Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) – Quo vadis? Birkhäuser Verlag, Basel und Boston. ISBN 3-7643-5341-4 (Basel), ISBN 0-8176-5341-4 (Boston).

Schmidt und Schorb 1995: Schmidt, M.; Schorb, A.: Stoffstromanalysen in Ökobilanzen und Öko- Audits.

Springer Verlag, Berlin. ISBN 3-540-59336-5.

Schmidt et al. 2004: Schmidt, A.; Jensen, A. A.; Clausen, A.; Kamstrup, O.; Postlethwaite, D.: A

comparative life cycle assessment of building insulation products made of stone wool, paper wool and flax. Part 1: Background, goal and scope, life cycle inventory, impact assessment and

interpretation. Int. J. LCA 9 (1), 53–66.

Schmincke und Grahl 2006: Schmincke, E.; Grahl, B.: Umwelteigenschaften von Produkten. Die Rolle der Ökobilanz in ISO Typ III Umweltdeklarationen. UWSF – Z Umweltchem Ökotox 18(2).

Schmitz et al. 1995: Schmitz, S.; Oels, H.-J.; Tiedemann, A.: Ökobilanz für Getränkeverpackungen. Teil A:

Methode zur Berechnung und Bewertung von Ökobilanzen für Verpackungen. Teil B:

Vergleichende Untersuchung der durch Verpackungssysteme für Frischmilch und Bier hervorgerufenen Umweltbeeinflussungen. UBA Texte 52/95. Berlin.

Schmitz und Paulini 1999: Schmitz, S.; Paulini, I.: Bewertung in Ökobilanzen. Methode des

Umweltbundesamtes zur Normierung von Wirkungsindikatoren, Ordnung (Rangbildung) von Wirkungskategorien und zur Auswertung nach ISO 14042 und 14043. Version ’99. UBA Texte 92/99, Berlin.

Schul et al. 1995: Schul, W.; Hirsinger, F.; Schick, K.-P.: A life-cycle inventory for the production of detergent range alcohol ethoxylates in Europe. Tenside Surf. Det. 32, 171–192.

SETAC 1991: Fava, J. A.; Denison, R.; Jones, B.; Curran, M. A.; Vigon, B.; Selke, S.; Barnum, J. (eds.):

SETAC Workshop Report: A Technical Framework for Life Cycle Assessments. August 18–23 1990, Smugglers Notch, Vermont. SETAC, Washington, DC, January 1991.

SETAC 1993: Society of Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry (SETAC): Guidelines for Life- Cycle Assessment: A „Code of Practice“. From the SETAC Workshop held at Sesimbra, Portugal, 31 March – 3 April 1993. Edition 1, Brussels and Pensacola (Florida), August 1993.

SETAC Europe 1992: Society of Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry – Europe (Ed.): Life-Cycle Assessment. Workshop Report, 2–3 December 1991, Leiden. SETAC Europe, Brussels.

Stalmans et al. 1995: Stalmans, M.; Berenbold, H.; Berna, J. L.; Cavalli, L.; Dillarstone, A.; Franke, M.;

Hirsinger, F.; Janzen, D.; Kosswig, K.; Postlethwaite, D.; Rappert, Th.; Renta, C.; Scharer, D.;

Schick, K.-P.; Schul, W.; Thomas, H.; Van Sloten, R.: European lifecycle inventory for detergent surfactants production. Tenside Surf. Det. 32, 84–109.

Suter et al. 1995: Suter, P.; Walder, E. (Projektleitung). Frischknecht, R.; Hofstetter, P.; Knoepfel, I.;

Dones, R.; Zollinger, E. (Ausarbeitung). Attinger, N.; Baumann, Th.; Doka, G.; Dones, R.;

Frischknecht, R.; Gränicher, H.-P.; Grasser, Ch.; Hofstetter, P.; Knoepfel, I.; Ménard, M.; Müller, H.; Vollmer, M. Walder, E.; Zollinger, E. (AutorInnen): Ökoinventare für Energiesysteme. ETH Zürich und Paul Scherrer Institut, Villingen im Auftrag des Bundesamtes für Ener gie wirtschaft (BEW) und des Nationalen Energie-Forschungs-Fonds NEFF. 2. Auflage.

Suter et al. 1996: Suter, P.; Frischknecht, R. (Projektleitung); Frischknecht, R. (Schlussredaktion): Bollens, U.; Bosshart, S.; Ciot, M.; Ciseri, L.; Doka, G.; Frischknecht, R.; Hirschier, R.; Martin, A.; Dones, R.; Gantner, U. (AutorInnen der Überarbeitung): Ökoinventare von Energiesystemen. ETH Zürich und Paul Scherrer Institut, Villingen im Auftrag des Bundesamtes für Energiewirtschaft (BEW) und des Projekt- und Studienfonds der Elektrizitätswirtschaft (PSEL). 3. Auflage. Zürich.

Svenska Miljöstyrningsrådet 2006: Climate Declaration, Carbon Footprint for Natural Mineral Water.

Registration number: S-P-00123. Program: The EPD®system. Program operator: AB Svenska Miljöstyrningsrådet (MSR), Product Category Rules (PCR): Natural mineral water (PCR 2006:7), PCR review conducted by: MSR Technical Committee chaired by Sven-Olof Ryding

([email protected]), Third party verified: Extern Verifier: Certiquality. Download from www.environdec.com.

Thomas 1995: Thomas, H.: A life-cycle inventory for the production of alcohol ethoxy sulphates in Europe.

Tenside Surf. Det. 32, 140–151.

Tiedemann 2000: Tiedemann, A. (Hrsg.): Ökobilanzen für graphische Papiere. UBA Texte 22/2000, Berlin.

Tukker et al. 1996: Tukker, A.; Kleijn, R.; van Oers, L.: A PVC substance flow analysis for Sweden.

Report by TNO Centre for Technology and Policy Studies and Centre of Environmental Science (CML) Leiden to Norsk Hydro, TNO-Report STB/96/48-III. Apeldoorn, November 1996.

UBA 1992: Arbeitsgruppe Ökobilanzen des Umweltbundesamts Berlin: Ökobilanzen für Produkte.

Bedeutung – Sachstand – Perspektiven. UBA Texte 38/92. Berlin.

UBA 1995: Umweltbundesamt (Hrsg.): Schmitz, S.; Oels, H.-J.; Tiedemann, A.: Ökobilanz für Getränkeverpackungen. UBA Texte 52/95, Berlin.

UBA 1997: Umweltbundesamt Berlin: Materialien zu Ökobilanzen und Lebensweganalysen. Aktivitäten und Initiativen des Umweltbundesamtes. Bestandsaufnahme Stand März 1997. UBA Texte 26/97.

Berlin. ISSN 0722-186X.

UBA 2000: Plinke, E.; Schonert, M.; Meckel, H.; Detzel, A.; Giegrich, J.; Fehrenbach, H.; Ostermayer, A.;

Schorb, A.; Heinisch, J.; Luxenhofer, K.; Schmitz, S.: Ökobilanz für Getränkeverpackungen II, Zwischenbericht (Phase 1) zum Forschungsvorhaben FKZ 296 92 504 des Umweltbundesamtes Berlin – Hauptteil: UBA Texte 37/00, Berlin September 2000. ISSN 0722-186X.

UBA 2000a: Kolshorn, K.-U., Fehrenbach, H.: Ökologische Bilanzierung von Altöl- Verwertungswegen.

Abschlussbericht zum Forschungsvorhaben Nr. 297 92 382/01 des Umweltbundesamtes Berlin.

UBA Texte 20/00, Berlin Januar 2000. ISSN 0722-186X.

UBA 2002: Schonert, M.; Metz, G.; Detzel, A.; Giegrich, J.; Ostermayer, A.; Schorb, A.; Schmitz, S.:

Ökobilanz für Getränkeverpackungen II, Phase 2. Forschungsbericht 103 50 504 UBA-FB 000363 des Umweltbundesamtes Berlin: UBA Texte 51/02, Berlin Oktober 2002. ISSN 0722-186X.

Udo de Haes 1996: Udo de Haes, H. A. (ed.): Towards a Methodology for Life Cycle Impact Assessment.

SETAC Europe, Brussels, September. ISBN 90-5607-005-3.

Udo de Haes und De Snoo 1996: Udo de Haes, H. A.; de Snoo, G. R.: Environmental certification.

Companies and products: Two vehicles for a life cycle approach? Int. J. LCA 1 (3), 168–170.

Udo de Haes und De Snoo 1997: Udo de Haes, H. A.; De Snoo, G. R.: The agro-production chain.

Environmental management in the agricultural production- consumption chain. Int. J. LCA 2 (1), 33–38.

UNO 1992: Agenda 21 in deutscher Übersetzung. Konferenz der Vereinten Nationen für Umwelt und Entwicklung im Juni 1992 in Rio de Janeiro – Dokumente – http://

www.agrar.de/agenda/agd21k00.htm.

Vattenfall et al. 2007: Product category rules: PCR for Electricity, Steam, and Hot and Cold Water Generation and Distribution. Registration no: 2007:08; Publication date: 2007-11-21; PCR documents: pdf-file; download from www.environdec.com. Prepared by: Vattenfall AB, British Energy, EdF – Electricite de France, Five Winds International, Swedpower and Rolf Frischknecht – esu-services Switzerland, Enel Italy. PCR moderator: Caroline Setterwall, Vattenfall AB, Sweden.

VDI 1997: VDI-Richtlinie VDI 4600: Kumulierter Energieaufwand (Cumulative Energy Demand).

Begriffe, Definitionen, Berechnungsmethoden. deutsch und englisch. Verein Deutscher Ingenieure, VDI-Gesellschaft Energietechnik Richtlinienausschuss Kumulierter Energieaufwand, Düsseldorf.

Wenzel et al. 1997: Wenzel, H.; Hauschild, M.; Alting, L.: Environmental Assessment of Products Vol. 1:

Methodology, Tools and Case Studies in Product Development. Chapman & Hall, London. ISBN 0-412-80800-5.

World Commission on Environment and Development 1987: Our Common Future (The Brundtland Report), Oxford. Deutsche Übersetzung: Der Brundtland-Bericht der Weltkommission für Umwelt und Entwicklung. Eggenkamp, Greven 1987.

Wright et al. 1997: Wright, M.; Allen, D.; Clift, R.; Sas, H.: Measuring corporate environmental performance. The ICI environmental burden system. J. Indust. Ecology 1, 117–127.