It provides diagnostic tools and research findings that can help countries identify policies and programs that can have the strongest impact on educational opportunities and outcomes for poor children and illiterate adults in their country context. It summarizes what we know from country experience and research about policies and programs that can solve the problems identified.

Education and Poverty

The importance of education for poverty reduction strategies

Research shows that investments in girls' education yield some of the highest returns of any development investment. It also directly supports improved family welfare, reducing some of the most devastating effects of poverty.

A conceptual framework for improving the education of the poor

And whether or not there are jobs for school students on the local or regional labor market greatly affects the demand for education. Even more crucially, the demand for education and the productivity of national educational investment are strongly influenced by labor market conditions, which in turn reflect the stability of macroeconomic policies and the rate and nature of economic growth.

Diagnosing Education Sector Performance

Key education outcomes

- Primary education completion rate

- Gender disparity in education enrollments

- Adult literacy rate

- Student learning outcomes

At the education system level (col. C), the challenge is to make the system – including public and private providers – work better for the poor through better policies, incentives and system management. Public expenditure analyzes follow funding from the top of an education system – the state budget – to the bottom, to schools and individual student aid recipients.

Analyzing expenditures

- System efficiency

- System quality

- System equity

Identifying causal factors: a decision tree approach

- Analyzing supply constraints

- Analyzing low demand

- Analyzing low learning achievement

The decision tree starts with the question: is the proportion of the age group that completes basic education acceptable or too low. In this case, the decision tree analysis links back to the analysis of public and private expenditures and the evaluation of public efforts (the share of GDP allocated to education), the availability of foreign aid, private expenditures and their progressivity and the share of budget allocated to basic education. The inability of the education system to employ a sufficient number of teachers is, especially in African countries, often associated with a level of teacher salaries in the country that is "too high", making it impossible to pay enough teachers from the budget to satisfy overall needs.

For average wages in other sectors of the economy, for people with equivalent education, (corrected for working hours). The central column of the decision tree analyzes weak demand, which can also be an important factor limiting enrollments. The far right column of the decision tree focuses on student learning, the ultimate outcome of an education system.

The third and rightmost section of the decision tree focuses on why the results may be unsatisfactory and what can be done to improve the learning. At this point, the decision tree analysis links back again to the earlier public expenditure analysis of the unit costs of basic education – the amount of public expenditure per student per year - which directly affects classroom conditions, including key factors such as class size, teacher qualifications, availability of teaching aids and so on. In many poor countries, and especially in the poorest regions of the country, there is malnutrition and disease.

Reform Strategies and Priority Programs

Education policies to improve outcomes for the poor

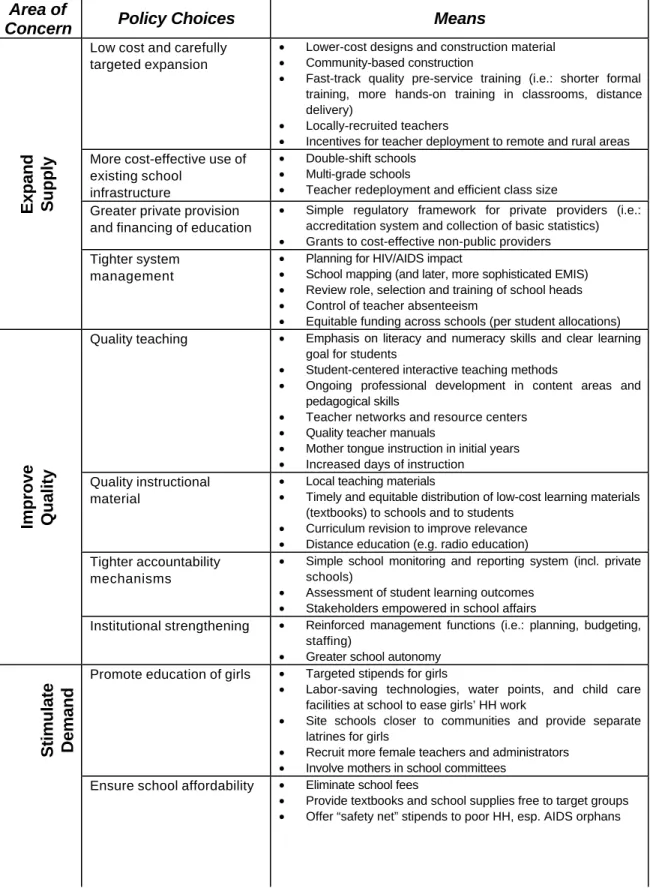

- Expanding supply

- Improving quality

- Stimulating demand and relieving household constraints

- Post-basic and tertiary education

Labour-saving technologies, water points and childcare facilities at school to facilitate girls' work in HH. Indirect or opportunity costs also greatly affect girls' educational opportunities; to compensate for these, countries such as Bangladesh, India, China, Pakistan and Guatemala have introduced special scholarship and monthly stipend programs for girls. These programs can be costly, but have shown a strong positive impact on girls' enrollments and have an economic justification in the social returns to girls' education.

Reduced distance to school tends to have a greater impact on girls' enrollment than boys, as parents are often more reluctant to let girls walk long distances to school. The provision of separate latrines for girls also has a significant impact on girls' attendance, especially for older girls. At the secondary level, there is evidence in countries such as Pakistan and Yemen that separate secondary schools for girls can boost girls' enrolment.

The lack of female teachers in many fields is a barrier to girls' enrollment, as parents in some cultures feel uncomfortable allowing their daughters, especially teenagers, to be taught by male teachers. Hiring more female teachers, and especially teachers familiar with the local community, has been an important strategy for encouraging parents to send girls to school in Pakistan and Nepal, and female teachers in all countries appear to serve as powerful role models. for girls, positively influencing girls. Attendance and persistence rates. The implementation of girls' education programs in countries such as Yemen, India, Bangladesh and Pakistan has also shown that female leadership helps.

In addition to the general benefits of parental involvement in school management and supervision discussed earlier, participatory school councils and village education committees that make a specific effort to involve mothers have been shown to have a positive impact on enrolments. of girls. The state of Uttar Pradesh in India, for example, increased the primary (gross) enrollment rate for girls from 50% to 98% in an eight-year period and reduced the school dropout rate from 60% to 31%.

Eliminating adult illiteracy

Since adults have high opportunity costs just to participate in classes and are always low-income individuals, basic education for adults should in principle be free. However, if the education and training provided is related to income-generating activities, some reimbursement may be explored. Encouraging a two-pronged approach: a) embedding literacy into existing interests such as agricultural and health advisory, cooperative groups or micro-enterprises, and b) offering focused literacy and numeracy training to those who are primarily interested in these skills.

However, use training opportunities to disseminate important information (health awareness, etc.) and always concretely relate literacy and numeracy skills to life, work, community and social issues and development programs. Ensure that facilitators receive adequate technical, moral and material support, such as the help of supervisors and professional networks, and that they are sufficiently accountable to their students to sustain their programmes. Strengthen the links between the education of children, especially those from very poor families, and the education of their parents.

Preparing a PRSP offers countries an important opportunity to rethink the relationship between the formal education system and non-formal education. A clear policy framework can help governmental and non-governmental providers of adult basic education to identify target groups, ensure that curricula include key health and other messages, deploy teachers/tutors efficiently, make use of existing buildings and coordinating community approaches. Government also has a vital role to play in establishing equivalency and certification standards for adult learners, collecting aggregate data on enrollment and completion rates for adult basic education, and developing a meaningful assessment tool for tracking progress in eradicate illiteracy among adults.

Other key policies

- Macroeconomic and fiscal policies

- Early child development programs (ECD)

- Health and nutrition

Compelling research in a wide range of countries has shown that early interventions to protect children's health, nutrition, emotional and intellectual development can reduce this gap so that poor children enter school on a more equal basis with their wealthier peers. While no single approach to the provision of early childhood care and education can be universally promoted, there is growing evidence that low-cost informal interventions, particularly those targeting disadvantaged children, can produce measurable benefits. Informal programs, often operated out of a community home with training and resources provided to a mother in the neighborhood, can be cost-effective alternatives to formal preschool programs, especially if the programs are designed to integrate health, nutrition, and interventions of early childhood development at the same time.

Informal early childhood programs are flexible in format and much less expensive to administer than formal kindergarten. Finally, low-cost informal ECD programs typically expand access to low-income children who would otherwise be missed and for whom, according to research, the potential benefits are greatest. A simple package of low-cost health and nutrition interventions aimed at school-age children is one of the single "best buys" a country can make in terms of cost-effective use of its health dollars17.

As countries make progress towards universal primary education, school health programs are increasingly important as some of the children most in need of health and nutrition support – the girl child, the rural poor, children with disabilities – have access to schools for the first time . A core group of simple and well-known interventions developed by WHO (World Health Organization), UNICEF (United Nations Children's Fund), UNESCO and the World Bank. Key to the cost-effective delivery of these interventions at the school level are cross-sectoral partnerships, particularly between the health and basic education systems, partnerships with the community and particularly PTAs (Prent Teacher Associations), and monitoring and evaluation to ensure that children's health status and school performance improve.

Identifying Feasible Actions and Setting Targets

- Identifying priority reforms

- Analyzing the time frame and institutional capacity for policies to work

- Analyzing the political feasibility of reforms

- Monitoring and evaluating reform implementation

- Estimating primary completion rates and other education indicators

- Template for disagregated enrollment

- Decision tree for analyzing education outcomes

Technical Note IV provides a summary of recent research on the cost-effectiveness of education in developing countries. One of the challenges facing HIPC and PRSP countries is to set explicit targets for improving key education outcomes that are both realistic and achievable, but which also 'stretch' the system to better performance as quickly as possible. 20 The tool for "Assessing Organizational Capacity" developed by Elie Orbach from the World Bank is a good example.

In one of the countries mentioned in table 1, for example, exceeds primary gross enrollments currently 100%. 21 For a useful overview, see Javier Corrales "The Politics of Education Reform: Bolstering the Supply and Demand; Overcoming Institutional Blocks", The Education Reform and Management Series II (1), World Bank, 1999. Ability to articulate a coherent vision for long-term development of the sector and to build public support for education reform.

For example, trying to get the express support of a teachers' union on key issues such as decentralizing teacher hiring and firing to the school/community level is likely to be impossible. A final common characteristic of successful education reform efforts is that they increase the transparency of the education system—making parents and the state more generally aware of how the system works. Education reform policy: strengthening supply and demand; Overcoming Institutional Blockades.” Education Reform and Management Series II (1). http://www1.worldbank.org/education/globaleducationreform/corrales.pdf).

The Role of the Private Sector in Education in Vietnam: Evidence from the Vietnam Living Standards Survey.” World Development. Washington, D.C.: World Bank Privatization Services Group, World Bank. http://www.worldbank.org/edinvest/thirdwave.htm).