Infection prevention and control are integral parts of patient care and are everyone's responsibility. Deputy Chief Nurse / Operations Leader, Infection Prevention and Control East Kent Hospitals University NHS Foundation Trust, Kent, United Kingdom.

Features contained within your textbook

The following pages show you how to make the most of the learning features in the textbook.

The anytime, anywhere textbook

Wiley E-Text

The VitalSource Bookshelf can now be used to view your Wiley E-Text on iOS, Android and Kindle Fire. For iOS: Visit the app store to download the VitalSource Bookshelf: http://bit.ly/17ib3XS.

CourseSmart

It also briefly discusses the challenges of infection prevention and control in acute trust and primary care settings. Note: Readers should always refer to the policies in their workplace's “Infection Prevention and Control Manual”.

Introduction

Background

In 1961 a report on the development of the post of Infection Control Nurse was presented to the Joint Advisory Committee on Research of the South West Region Hospital Board by Dr Brendan Moore, Director of the Public Laboratory in Exeter. Although the appointment of a nurse as a full-time member of the Infection Control Team was opposed nationally by consultants, Infection Control Nurses were subsequently appointed in many other hospitals.

The problem of HCAIs

The first report by the NAO (2000) stated that the prevention and control of HCAI were not seen as priorities in health services and that the strategic management of hospital-acquired infections needed to be strengthened at national and NHS Trust level, as was clear. that the NHS had no idea of either the scale of the problem or the resulting financial burden. Implementing new healthcare-associated infection legislation with the introduction of the Health Act 2006: Code of Practice for the Prevention and Control of Healthcare-Associated Infections (DH, 2006).

Reflection point

In the years between the publication of the second Report and the third Report, in 2009, a large number of DH-led drives and initiatives were developed and implemented. Launched in 2005 by DH of Saving Lives, an outreach program to reduce healthcare-associated infections including MRSA.

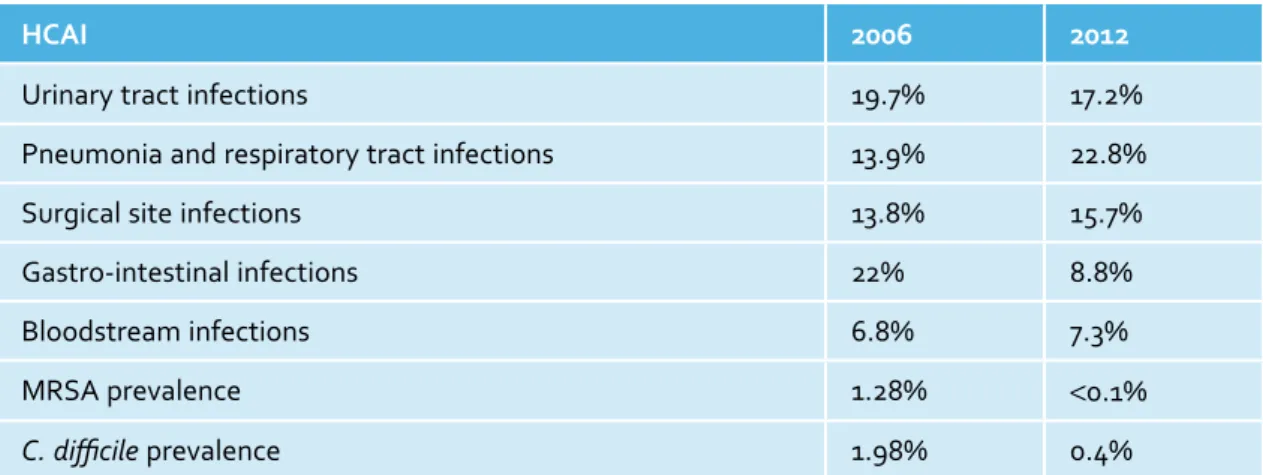

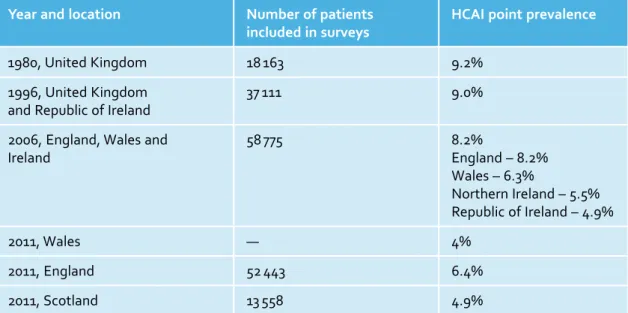

HCAI point prevalence surveys

Source: Data from Meers et al., 1981; Emmerson et al., 1996; Nosocomial Infections Society and Association of Infection Control Nurses, 2007; Welsh Healthcare Associated Infection and Antimicrobial Resistance Programme, 2011; Health Protection Agency, 2012; Health Protection Scotland and NHS National Services Scotland, 2012. Boxes 1.2 and 1.3 outline the factors contributing to the increase in HCAIs and the impact that HCAIs have on patients and the NHS.

The challenge of disease threats old and new

Hospitals are no longer able to cope with the patient population – design, fit-out, condition and maintenance of buildings and environment. Increased bed occupancy Increased treatment time for patients Increased movement of patients Lack of isolation facilities.

SARS

Pandemic influenza

Changes within the NHS and the provision of healthcare

Secondary versus primary care: infection control in acute trust and primary care settings

NHS acute trusts (secondary care)

Resources and facilities: medical devices (equipment and instruments) – single use (disposable) and reusable; facilities for cleaning and disinfecting medical devices that meet national best practice standards; sufficient staff and an appropriate mix of skills; and storage of equipment and medical devices. Due to an aging population, changes in healthcare delivery, the reemergence of old infectious diseases, the emergence of new and the emergence of new pathogens, the threat of infections and infectious diseases is ever present.

Responsibility for the prevention and control of healthcare-associated infections does not rest with the Infection Prevention and Control Team. This chapter describes the role of the Infection Prevention and Control Team and gives examples of the scope and responsibility of the Team.

The role of the Infection Prevention and Control Team

Understand the implications of non-compliance with the Infection Prevention and Control Code of Practice and related guidelines. Audit compliance with the code of practice for the prevention and control of infections and related guidelines (DH, 2010).

The challenges of working as an Infection Prevention and Control (IP&C) Specialist Nurse

The role of Infection Control Link Practitioners

Responsibility, accountability and duty of care

Competency

Administration of the methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) decolonization protocol (the patient may be inadequately decolonized if the 'decol' is not administered correctly - see Chapter 20). The Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC) Code, The Code: Standards of Conduct, Performance and Ethics for Nurses and Midwives (NMC, 2008), states that nurses 'must recognize and work within the boundaries of.

Documentation

Performing certain clinical interventions or practices without the appropriate knowledge, skills and training puts patients at risk of HCAI and also puts healthcare professionals at risk.

Avoidable versus unavoidable infections

The Health and Social Care Act 2008: Code of Practice on the Prevention and Control of

The Health and Social Care Act 2008: Code of Practice on prevention and control of. The reader should be aware that compliance with the Code is implied in each chapter and integrated into each topic/aspect of infection prevention and control described/discussed.

Root Cause Analysis (RCA)/Post Infection Review (PIR)

Who administered the decoction – was it self-administered by the patient, or was it administered by nursing staff. Was the person taking the blood culture competent to do so (proof of competence required).

Audit

Observational audits of compliance with standard precautions (use and disposal of personal protective equipment; handling and disposal of sharps; segregation of healthcare waste). Box 3.2 Some examples of larger infection control audits that may be conducted annually or more frequently.

Surveillance

IP&CT must work with staff on infection prevention and control audits; they can be a powerful tool for change and should be viewed positively, either as an indicator of the effectiveness of clinical practice or as a benchmark for raising standards and improving patient care. Audit results should also be shared at staff meetings, be part of the agenda at clinical leadership meetings, and included in monthly and quarterly infection control reports for departments, directorates, and the board of trustees.

Alert organism surveillance

Alert conditions

Surveillance of notifiable diseases

Mandatory and voluntary surveillance MRSA bacteraemia

The data collection form can be viewed on the HPA/Public Health England website (HPA, 2013g). For information on the clinical significance of the GRE, see Fact Sheet 3.2 of the companion website.

Surveillance of surgical site infections

Surveillance enables early identification of diseases, infections and infectious diseases that may lead to outbreaks and helps identify risk factors for the development of HCAIs. Done right, audit and surveillance can be tools for change, leading to improvements in patient care both locally and nationally.

Further reading

Whether a cluster, a PII or an outbreak, these 'incidents' can seriously disrupt the delivery of healthcare, be costly and labour-intensive, and cause unnecessary anxiety and stress for patients, the public and affected staff. They can be devastating when lives are lost, and can hugely erode public confidence in the NHS and local services.

Recognising a cluster, a period of increased incidence and an outbreak

They can range from the relatively small and easy to control (eg, a cluster of methicillin-resistant Staphylo-coccus aureus [MRSA] colonizations in a medical ward, or a period of increased incidence of Clostridium infection difficile in a community hospital) to more serious and often larger outbreaks affecting public health in a wider context; Eruptions can affect a local population in a certain geographic area, or they can pose a global threat. Consistent application of good infection control practice and compliance with infection control and public health policies and legislation means that many incidents are often avoidable; where non-compliance can be demonstrated to have caused or contributed to the incident, the potential consequences can be far-reaching and lead to changes in practice not only locally but also nationally.

Cluster

The investigation and subsequent management of clusters, periods of increased incidence (PIIs) and outbreaks of infection (or colonization) are aspects of infection control work that many healthcare workers are likely to experience and be actively involved in. This chapter aims to define clusters, PIIs and outbreaks for healthcare workers and provides a brief insight into the various factors that need to be considered and investigated in the event of a cluster, PII or outbreak.

Period of increased incidence

Whether a cluster is classified as an outbreak or not leads to an outbreak depends on several factors, including the time frame, whether other patients in the ward subsequently acquire the same infection and whether typing (see Chapter 7) identifies the patients as the the same tribe.

Outbreak

The source of the outbreak was an air conditioning unit in an arts complex in Forum 28, the Town Civic Centre, which was run by Barrow-in-Furness Borough Council. Outbreaks have also occurred in central London; one at the headquarters of the BBC in 1988 affected 79 people and resulted in three deaths (Department of Health, 2002).

Look-back exercise

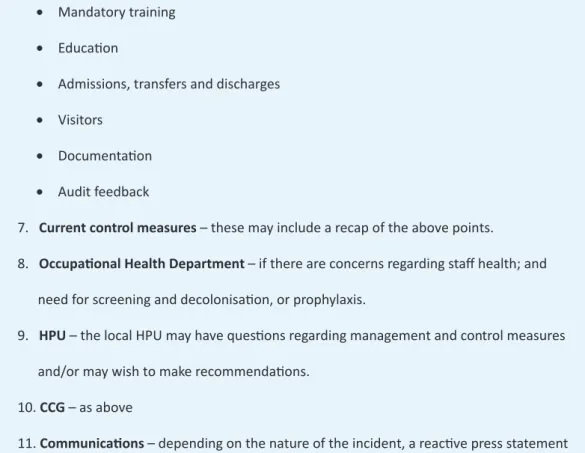

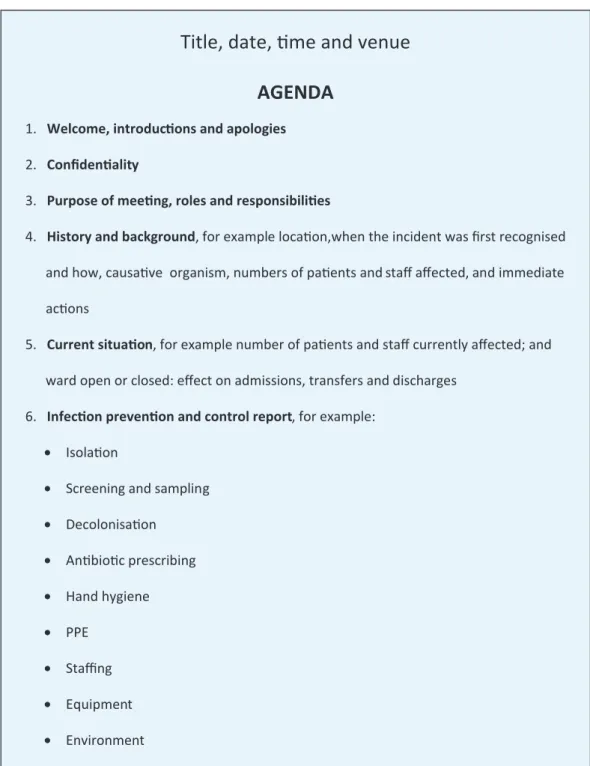

Arranging a cluster, PII or outbreak control group meeting: who to invite and

Hand hygiene: Are the staff's hand hygiene assessments up to date; what is the average weekly compliance with the department's observational hand hygiene audits; how compliant the staff is towards. Documentation and communication: Is patient intervention documented; are infection control patient management plans and processes completed; is the registered information correct; is there evidence that information registered and passed on by IP&CT has been acted upon.

MRSA

In 1996, four babies in a neonatal unit in the United Kingdom developed fungal infections contracted from wooden tongue depressors used as limb splints to secure vascular access devices. A fungus belonging to the Rhizopus microsporus group was subsequently isolated from 10% of the wooden tongue depressors kept on a surgical trolley, but not from the tongue depressors kept in an unopened box (Public Health Laboratory Service, 1996).

Investigating a cluster of ward-acquired MRSA colonisations

The ward: Did the patient use a shower or bath, and if so, which one, when and how often. If the patient had a bath, it is an Arjo non-spa bath or Arjo spa bath.

Tuberculosis (smear positive): if the index case is, or was, a hospital in-patient

Estate issues: Are there any 'dead legs' or areas of redundant pipework; are the locations of all high or low use water points known; is there a program of flushing low-use water outlets; is there a program of daily flushing of all water outlets; and are there any toilets or bathrooms used as storage facilities, which impede the use of the facilities for their intended purpose and restrict access for flushing. In other words, travel abroad, hotel accommodation (air conditioning?) or use of hot tub or spa bath in a hotel or leisure complex.

At the meeting and after: actions and closure of the incident

At the meeting, after all the necessary reporting, actions will be identified and assigned to individuals who will be responsible for ensuring that they are implemented within a specified timeframe. Getting ahead of the curve: A strategy for combating infectious diseases (including other aspects of health protection).

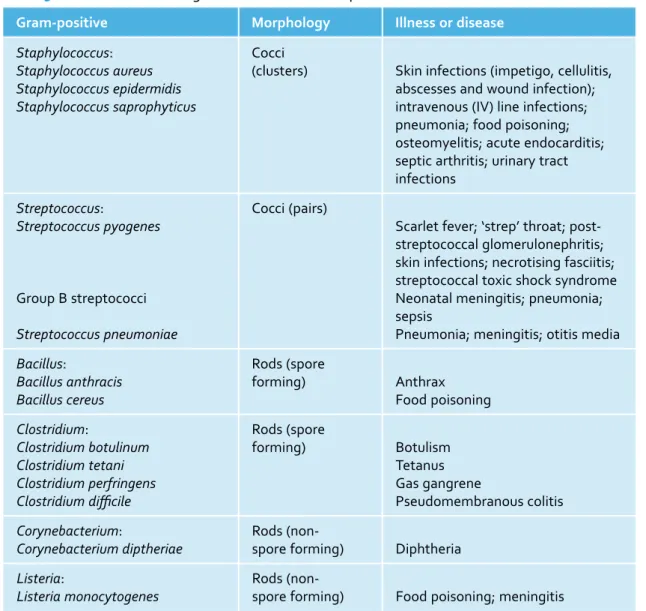

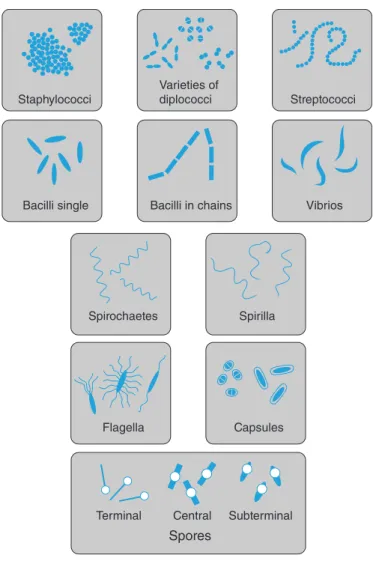

Bacteria

To understand how bacteria and viruses replicate, invade and establish in the human body, resulting in colonization or infection, a basic knowledge of their classification and structure is necessary. Understand the main virulence factors of bacteria and their importance in the process of colonization and infection.

Bacterial structure

The main component of the cell wall is peptidoglycan (or murein), which is a polymer (a long molecule consisting of structural units and repeating units) of peptidoglycan chains linked by smaller protein chains. The thickness of the cell wall and its composition vary depending on the type of bacteria.

Bacterial classification

Cytoplasm consists of water, enzymes, waste products, nutrients, proteins, carbohydrates and lipids, all of which are necessary for the metabolic functions of the cell. Embedded within the cytoplasm is the cell's chromosome, its DNA molecule, which controls and initiates cell division and other cellular activities.

Virulence factors: slime, capsules and biofilm

Bacterial biofilms are of great medical importance because they are notoriously difficult to penetrate the host immune system, have been reported to be at least 500 times more resistant to antibiotics than 'regular' bacterial cells (Petri et al., 2010), are highly resistant to phagocytosis (Watnick and Koiter, 2000) and can cause persistent infections (Chen and Wen, 2011). They can contaminate hot water tanks, shower heads and air conditioners that use water and develop on the surfaces of endoscope tubing (Petri et al., 2010).

Spore formation

While bacteria will adhere to virtually any available surface with the exception of plastic and glass, they are particularly fond of indwelling devices such as intravenous cannulas and urethral catheters, as well as prosthetic implants.

Flagella

Pili (fimbriae)

The production of invasive enzymes

Toxin production

An unfortunate consequence of administering antibiotics to a patient with Gram-negative sepsis is that they may initially worsen the patient's condition. Exotoxins are produced intracellularly and secreted by Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria (with the exception of Listeria monocytogenes, a Gram-positive rod that causes meningitis in newborns and immunocompromised individuals, and which produces endotoxin) (Gladwin and Trattler, 2004).

Plasmids

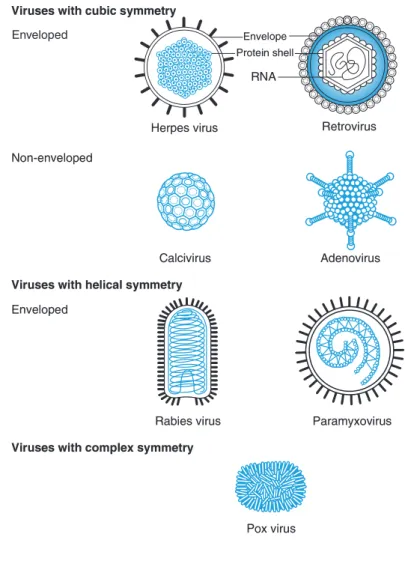

Viruses

Structure

Replication

Transcription, translation, and replication occur as new viral particles are produced in the host cell. The host cell then bursts and releases as many as 10,000 new viral particles (Collier et al., 2011a), which then infect other host cells.

Some medically important viruses

Symptoms include enlargement of the lymph nodes behind the ears, in the neck and armpits, along with pyrexia, malaise, conjunctivitis and a rash that first affects the head and neck before spreading to the trunk (Collier et al., 2010e) . Part of the population will have immunity to the virus and vaccination is a preventive measure in people without immunity or who fall into risk categories.

Prions

Does an understanding of the virulence factors of bacteria and viruses, particularly those related to the bacterial cell wall and toxin production, make healthcare personnel more likely to appreciate and understand the importance of compliance with standard infection control precautions. A report prepared by the PVL subgroup of the Healthcare-Associated Infections Steering Group.

General points

Unfortunately, many samples received in the laboratory are substandard and therefore not considered viable for a number of reasons that can and should be easily avoided. Be able to obtain or assist in the collection of clinical specimens commonly requested for the detection of infections – urine, sputum, swabs, faecal specimens, throat swabs, nasal swabs, cerebral spinal fluid and blood.

Specimens must be collected in the appropriate container

Taking the correct specimen

Obtaining a specimen at the correct time

The labelling of specimens and the specimen request form

The "age" of the specimen is important - some organisms are fragile and will die once they leave the body, which will obviously make them difficult to identify. Box 6.1 identifies the clinical information that should be provided on the sample request form, where appropriate or applicable.

The investigation required

Danger of Infection’ labelling

Prompt delivery to the laboratory

Under RIDDOR, employers are required to report accidents, dangerous incidents and cases of ill health among employees to the Health and Safety Executive (HSE). Further information regarding biological agents and hazard categories can be found in the Health and Safety Executive and Advisory Committee on Hazardous Pathogens (2004) publication The Approved List of Biological Agents.

Commonly requested clinical specimens

Urine

Indications for collection

Obtaining an MSU

Obtaining a catheter specimen of urine (CSU)

Sputum

Obtaining a sputum specimen

Wounds

Obtaining a wound swab

Faeces

Obtaining a stool specimen

As discussed in this chapter, the location and nature of the wound must be clearly indicated on both the swab and the request form.

Rectal swabs

Throat swabs

Obtaining a throat swab

MRSA screen (nose and axillae)

Blood culture

Box 6.6 provides indications for blood culture collection, and Box 6.7 provides best practices for preventing contaminated blood cultures. Use a 2% chlorhexidine gluconate in a 70% alcohol swab to decontaminate the tops of the blood culture bottles (these are clean but not sterile) and allow to dry (approximately 30 seconds) before inoculating the bottles.

Cerebral spinal fluid

Document the procedure in the patient's notes - indication for blood culture; Date and time; place of blood culture; signature and printed name; and bleep and phone number. In the event that the patient has MRSA bacteremia, the person who obtained the blood culture should be contacted by the Infection Prevention and Control Team and asked to (1) describe the step-by-step procedure he or she used and (2) to provide evidence that he or she has completed appropriate training and passed competency assessment.

Reflection point

Note: Completion of a pre-printed 'Blood Culture Collection Label Registration' containing the above information and a statement that the blood culture has been collected in accordance with Trust policy by a healthcare worker who is competent to undertake the procedure, helps to ensure that best practice has been followed. Infection at Work: Risk Control – A Guide for Employers and the Self-Employed to Identify, Assess and Control the Risk of Infection in the Workplace.

Bacterial growth

To detect, identify, and treat bacterial and viral infections, the infecting microorganisms must be cultured under laboratory conditions that mimic the conditions under which they would grow optimally in a human host. The reader should note that these tests may vary depending on the facilities available at individual laboratories, and some samples may need to be sent to other laboratories.

Nutrients

Understand the basic principles of polymerase chain reaction, immunofluorescence, serology and tissue culture to aid bacterial and viral detection.

Temperature

Pyrexia, which often accompanies many diseases, is useful in fighting infection and is actually a protective response, as most pathogens replicate best and achieve their optimal growth at temperatures of 37°C or below. Legionella bacteria thrive in water temperatures of 20-50 °C, but are unable to withstand temperatures of 60 °C or above, where they die quickly.

Moisture

Legionella growth in artificial water systems can therefore be controlled by keeping the cold water temperature below 20°C and the hot water temperature above 60°C.

Oxygen

Cell division

This means that each subsequent cell division must therefore result in exact DNA replication. Bacterial growth has been demonstrated in the laboratory on culture media where the number of cells increases exponentially with time, and this stage of the bacterial growth cycle is known as the exponential or logarithmic phase of growth (Barer, 2007).

Bacterial culture

These mutations are one of the factors that contribute to antibiotic resistance, which is discussed in Chapter 10. The amount of time it takes for the cell to divide is known as the generation or doubling time, which varies between bacterial species.

Culture media

Inoculation of culture media

Culturing viruses

Gram‑staining

Processing specimens

MRSA Culture

If it is resistant to the antibiotic, the organism will grow to the edge of the disc. A mucolytic is added to the sputum to break it up, and that's it.

Other laboratory techniques

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR)

Latex agglutination

Immunofluorescence

Serology

Typing

Genome sequencing

To care for patients with an infection or infectious disease, a basic understanding of immune system function and the pathogenesis (development) of infection is beneficial. Understand how the clinical features of infection arise by relating them to the function of the immune response.

The innate, or natural, immune response

This is especially important given that many of the clinical features of infection are due to the defense mechanisms used by the immune system. Understand the differences between innate and adaptive immunity and the role specialized components of the immune system play in fighting infection.

The skin

There are two branches of the immune system that work independently of each other and together: the innate or natural immune response and the adaptive or acquired immune response. Because immunology is a complex topic and requires more than one chapter to be adequate (which is beyond the scope of this book), this chapter aims to provide a broad and concise overview of the disease process linking the immune response, the chain of infection, and the pathogenesis of infection—common themes , which will be linked to Chapters 20-24 in Section 4 of this book.

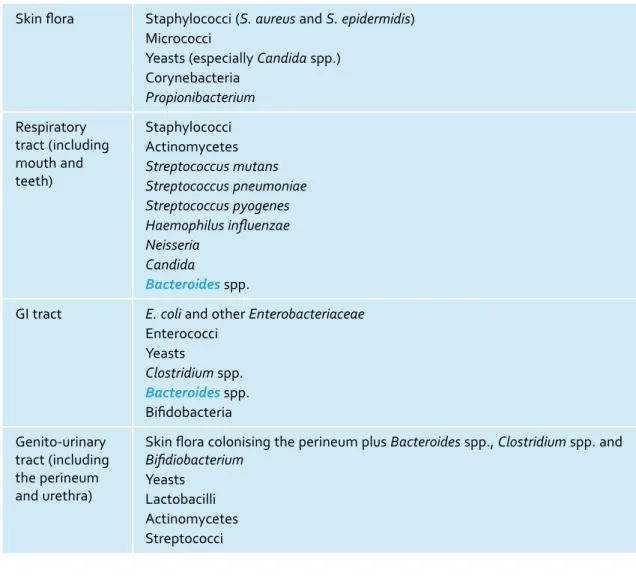

Resident body flora

The shedding or shedding of dander also aids in the elimination of microorganisms (Dieffenbach et al., 2009), although this could also contribute to environmental pollution and cross-contamination if a person were heavily colonized with a potential pathogen such as methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). Despite these external defenses, any break in the skin resulting from a traumatic injury, a surgical wound (see Chapter 18), or the insertion of an IV cannula (see Chapter 16) will create an immediate gateway into the body through which pathogens can quickly enter body tissues and the enter and enter bloodstream.

Defence mechanisms of the respiratory, GI and genito-urinary tracts

While the genitourinary tract is sterile above 1 cm distal to the urethra, the perineum is colonized by skin and intestinal flora, which may enter the normally sterile environment, especially if the normally closed urethra is open due to the presence of a urethral catheter, which acts as a 'bladder ladder' (see Chapter 17). Usually, however, the normal mechanism of bladder emptying and the flushing effect of urine will flush out any potential invaders.

White blood cells

Within the large intestine, the resident intestinal flora (1010 organisms per gram of faeces) (Ryan and Ray, 2010) competes for nutrients with and inhibits the growth of other bacteria that can become pathogenic if the balance of the microbial population is disturbed (see Chapter 22 about Clostridium difficile). The ciliated epithelium and mucociliary 'carpets' that line the airways trap invading micro-organisms and fan out the bacteria.

Cytokines, chemotaxis and phagocytosis

Cytokines bind to cell surface receptors on pathogens and act as chemical messengers, part of an "extracellular signaling network" that directs and regulates every function of the innate and adaptive immune responses, including inflammation and proliferation (multiplication) of T and B clones. lymphocytes (Roitt et al., 2001). When the phagocytic cells encounter a pathogen, dead or dying cell debris, or other foreign material, they bind to it; it is then engulfed by a pseudopod, an extension of the phagocytic cell membrane, and killed by the combined activity of digestive enzymes and a transient increase in oxygen uptake (breathing blast), which destroys the cell.

Macrophages

Cytokines have been implicated in infections such as influenza and severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) (Osterholm, 2005) and, in the United Kingdom in 2006, following a drug trial involving a single intravenous injection of a new antibody monoclonal (Suntharalingam et al. ., 2006; St Clair, 2008). Phagocytic cells migrate across capillary walls and through tissues to the affected area by the process of chemotaxis, which is a directed movement toward chemical attractants, such as products of damaged tissue, blood products, and products produced by mast cells and neutrophils (Stains et al., 1993; Dieffenbach et al., 2009).

The adaptive, or acquired, immune response

The first encounter with an antigen elicits a primary response, and after this initial exposure, a stronger and more rapid response is generated upon a second encounter with the antigen or pathogen (Roitt et al., 2001). They are produced in the bone marrow and are found throughout the body in the blood, lymph fluid and lymph tissue, where their role is to recognize and respond to antigens (Staines et al., 1993).

T lymphocytes

B lymphocytes

Antibodies

Complement

There are three complement activation pathways: the classical pathway is initiated by the formation of antigen-antibody complexes, the alternative pathway by the presence of microbial pathogens, and the lectin activation pathway by a protein formed in the liver called mannose-binding lectin (MBL). named. which is activated by carbohydrate molecules found on the surface of pathogens (Roitt et al., 2001; Sompayrac, 2008a).

The immune response and allergy

Hypersensitivity reactions

When the allergen is encountered, the mast cells and basophils degenerate and release histamine (which is a potent activator of the immune response) and prostaglandins. Since mast cells and basophils are located under the skin and in the mucous membranes of the eyes, nose, lungs and throat, this is where the majority of the clinical signs of an allergic reaction are seen (Sompayrac, 2008b).

The reservoir is the place where the organism usually lives, and where it will find the nutrients and moisture supply necessary for its growth and survival. As discussed in this chapter, the human body is the reservoir for the bacteria that colonize the skin, gut and respiratory tract.

Understanding the chain of infection

- causative organism

- and 4: portal of exit and portal of entry

- mode of transmission

- the susceptible patient

These include the respiratory and digestive tracts and the skin and mucosa, with organisms carried in blood and body fluids, in respiratory droplets and on the surface of the skin. Age: With increasing age, the immune system's ability to fight infection naturally declines.

Colonisation, infection and the inflammatory response

Neutrophils can become severely depleted due to bone marrow suppression, causing a potentially life-threatening condition known as neutropenia, which is a neutrophil count of less than 1000/. Treatment: The balance of the resident microbial population of the large intestine can be adversely affected by the administration of antibiotics.

Colonisation

Infection

Overstimulation of the immune system can result in damage to the host and possibly death. This short chapter aims to provide an overview of the pathogenesis of sepsis and its infection control management along with the infection control management of neutropenic sepsis.

Sepsis and septicaemia

Sepsis is the 'umbrella' word often used to describe systemic infection; 18 million people die from sepsis worldwide each year (Slade et al., 2003). Septicemia is the systemic disease that results from the uncontrolled spread of bacteria or their toxins through the bloodstream and is the leading cause of death in intensive care units (Robson and Newell, 2005; Wheeler, 2009).

Sepsis definitions

Sepsis is defined as SIRS with a suspected or confirmed infection and accompanied by two or more of the SIRS criteria (Bone et al., 1992). Severe sepsis is said to occur if there is a known or suspected infection, along with two or more SIRS criteria plus more than one sign of acute organ dysfunction, which may involve any major body organ.

The pathogenesis of septic shock

Toxin release

Activation of the complement system

Systemic effects

The management of sepsis and septic shock

Box 9.2 lists the sepsis six – six tasks which can be initiated and undertaken by any team of healthcare professionals (eg nursing and medical staff in a general ward setting) and which must be delivered within one hour of recognition of sepsis (www. .survivingsepsis .org). Box 9.3 summarizes the infection control investigations that should be performed to determine the cause of sepsis.

Neutropenic sepsis

The choice of antibiotic, which may require combination therapy, should be based on sensitive samples of microorganisms in the community and hospital, should be active against likely bacterial and fungal pathogens and should penetrate to the suspected source of sepsis (Ahrens and Tuggle, 2004; Robson and Newell, 2005). Attempts should also be made to control the source of the sepsis, such as removal of potentially infected invasive devices, debridement of any necrotic tissue, and drainage of any abscesses if present.

Confirming a diagnosis of neutropenic sepsis

Enterobacteriaceae (Klebsiella, Enterobacter and Serratia species) (see Chapter 10 and Fact Sheet 9.3 on the companion website). Aspergillus species (see fact sheet 9.1 on the companion website) Cytomegalovirus (CMV) (see fact sheet 9.2 on the companion website) Herpes zoster virus (see fact sheet 3.11 on the companion website).

Clinical considerations

Blood culture and antibiotics

Admission and isolation

Clinical practice points: infection control precautions

Note: Comprehensive information on national and global campaigns related to antibiotic prescribing and antibiotic resistance, including bulletins, reports and guidelines, can be found at the following websites: hpa.org.uk, www.dh.gov, www.cdc. gov , www.who.int, scot.nhs.uk and www.wales.nhs.uk. Understand the importance of ESBL and carbapenem resistance and the management of infection control of resistant organisms.

Part A

It goes on to explain how antibiotics work, the problems of antibiotic resistance and the importance of antimicrobial stewardship. Part B looks at the problems associated with resistant Gram-negative rods, and the major threat to public health posed by carbapenem resistance.

The discovery of penicillin

Very few new antimicrobials have been developed since the late 1980s and early 1990s, and with the continued rise of multidrug resistance, particularly among Gram-negative bacteria, antimicrobial resistance has been recognized as a major public health threat and a global concern since the late 1990s ( Department of Health [DH], 2002). In 2013, the Chief Medical Officer (CM0), chief medical adviser to the UK government, announced that antimicrobial resistance should be placed on the National Security Risk Register and carry the same level of 'political importance' as MRSA and C.

Penicillin re-discovered

The emergence of resistance

How antibiotics work

Spectrum of activity

Mode of action

Resistance to antivirals has also developed markedly, with serious implications for the treatment of patients with HIV or hepatitis B, vulnerable patients at risk for opportunistic infections and influenza (Hayden, 2006; Regoes and Bonhoefter, 2006; WHO, 2008; Ghany and Doo 2009, Hurt et al., 2011). Polymixins, such as colistin, disrupt the bacterial cell membrane, causing the cell to break open (Ryan and Drew, 2004).

Routes of administration

Side effects

Antimicrobial resistance

Inherent or acquired resistance

Plasmids and transposons

Conjugation

Transduction and transformation

Other mechanisms of resistance

Factors leading to the emergence of resistance and problems within the healthcare setting

Survival of the fittest, or selection

The driving force behind the whole 'resistance problem' has been the widespread use of antibacterial drugs and the misuse and overuse of antibiotics worldwide in the treatment of humans and animals. They are administered continuously at subtherapeutic levels, often in feed, and the agents used are either the same or belong to the same classes as those used to treat human infections (WHO, 2011).

Antibiotic prescribing in the healthcare setting

If antibiotic selection pressure is removed (ie by temporarily or permanently limiting antibiotic use within a population), mobile resistance genes carried by "promiscuous" plasmids may be lost and the "host" bacterium may become susceptible. Box 10.1 lists some of the factors related to prescribing that have exacerbated the development of resistance.

Antimicrobial stewardship

In 2012, the HPA published the preliminary results of the first ever national point prevalence survey of antimicrobial use in England, which had been carried out as part of a national point prevalence survey on healthcare associated infections (HCAIs). Enterobacteriaceae exist as part of the normal intestinal flora (coliforms) and they harmlessly colonize the colon and/or the environment.

Part B

They can be present in the intestine in large numbers, posing a risk to patients undergoing procedures in the hospital. They can be transferred to other sites on patients by their own hands or to other patients via the hands of healthcare workers and through contact with contaminated equipment.

Specific antibiotic-resistant organisms

Extended-spectrum beta-lactamases (ESBLs)

They can be multi-antibiotic resistant, which is defined as resistant to any aminoglycoside, such as gentamicin, and also resistant to any third-generation cephalosporin, such as cefuroxime and cefotaxime. Some isolates are also now resistant to the carbapenems such as imipenem and meropenem, and these are referred to as MRAB-C, a clone established in hospitals in London and the South East of England.

Carbapenem resistance

Do not throw body fluids into the wash basin - use the soiled toilet area. In the United States, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has published an extensive toolkit for managing these organisms (CDC, 2012).

Clinical practice points: the infection control management of patients colonised or infected

This chapter looks at the implementation of patient isolation in conjunction with standard infection control precautions. Understand the importance of patient isolation and cohort nursing as part of infection control standard precautions.

Compliance with the Health and Social Care Act 2008

Determining the need for isolation and risk assessment are discussed, along with different methods of isolation, such as negative pressure facilities and cohort nursing, and the challenges of isolating patients in different care areas. Understand how to use infection control standard precautions in settings where patients cannot be isolated in a single room or cohort area.

Standard precautions

Care homes are not expected to have dedicated isolation facilities, but are expected to implement standard and isolation precautions.

EPIC and NICE guidelines

The purpose of isolating patients and different categories of isolation

Source (standard) isolation

Source isolation covers all organisms and infections with the exception of respiratory isolation for suspected or confirmed tuberculosis and rare infectious diseases. Strict isolation is for very rare infectious diseases (eg viral haemorrhagic fever [VHF], SARS and H5N1 influenza [see Chapter 5], pulmonary anthrax and rabies) and will be carried out in a designated high-security infectious disease unit.

Protective isolation (see Chapter 9) Cohort nursing

It is important that all staff understand that it is not the patient that is isolated, but the organism and its mode of transmission, and it is extremely important that this is clearly communicated to patients and their relatives and carers. A cohort may consist of an entire group of colonized or infected patients, in which case the patients should be cared for by specific staff in a specific area (section) of the ward, although it is accepted that this is not always immediately achievable.

Isolation and risk assessment

Infection control precautions within specialist areas

Generally, the patient's nursing notes and TPR (temperature, pulse and respirations) and prescription charts are kept outside the room. If the patient is on a specific infection control pathway or patient management plan, this should be done every shift or day as needed.

General points regarding the infection control management of infected and colonised patients

The door should be kept closed (if this is not possible, eg the door should be kept open so that the patient can be easily observed, this should be documented in the nursing notes each shift). Alcohol hand rub should be available outside the room entrance and inside the room at the point of care.

Negative-pressure isolation

Rehabilitation should not be compromised or delayed because the patient is isolated in a single room. Physiotherapy, occupational therapy and speech therapy can be crucial to the patient's recovery and discharge home, and unless the organism is highly transmissible, there is no reason why most activities and risks cannot be effectively managed.

The psychological effects of isolation

Care of deceased patients

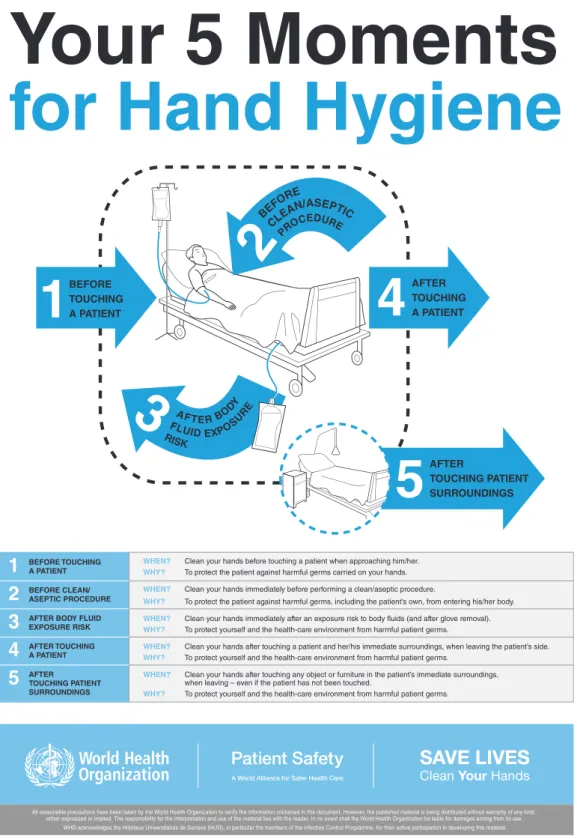

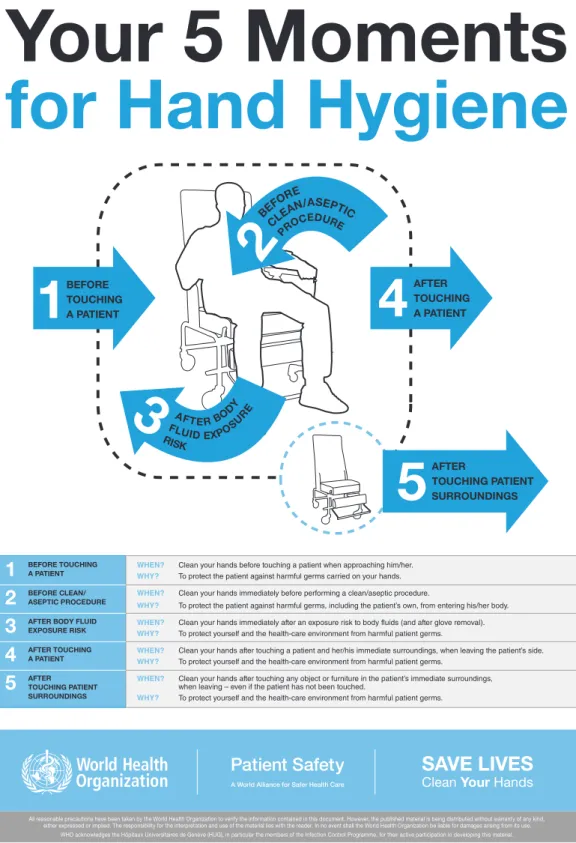

This chapter explains the difference between resident and transient microorganisms on the skin and hands; how cross-infection occurs through hands; while washing hands with soap and water, as well as decontamination of hands with hand rubs or alcohol-based gel, should be done; the advantages and disadvantages of each method and the importance of undertaking hand hygiene and hand decontamination at the point of care in accordance with the 5 Moments for Hand Hygiene. Understand the importance of undertaking hand hygiene at the point of care (the 5 moments of hand hygiene).

Ignaz Semmelweis

In 2005, the World Health Organization (WHO) launched the first global patient safety challenge, Clean Care is Safe Care, to promote hand hygiene best practice worldwide and highlight the importance of hand hygiene in reducing healthcare-associated infections. It has been estimated that "good" hand hygiene practice could contribute to a reduction of healthcare associated infections (HCAI) by 15–30% (Pratt et al., 2001; National Audit Office, 2004).

The microbial flora of the skin

80% of microorganisms reside within the first five cell layers of the epidermis (Ostrander et al., 2005) and approximately 10 million aerobic bacteria reside in one square centimeter of skin (Taylor, 2006). Of course, it is now universally recognized that the hands are the primary route through which cross-infection occurs and that hand hygiene is the single most important factor in infection control (Gould, 1991; Pratt et al., 2001; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC, 2002; Pratt et al., 2007; Sax et al., 2007; National Patient Safety Agency, 2008; Allegranzi and Pettit, 2009; Edmond and Wenzel, 2010).

Resident skin flora

Transient skin flora

How cross-infection via the hands occurs

The transfer of microorganisms to the hands of health care workers is the most common mode of transmission in the health care sector, and Pittet et al. Organisms are present on the patient's skin, or are shed on objects around the patient's environment.

Hand hygiene

When microorganisms transmitted by the hands become established on a patient, subsequently causing infection in susceptible sites.

Hand washing

When microorganisms are introduced directly into sensitive sites, such as surgical wounds and intravenous cannula sites. Hands can become contaminated with bar of soap (hence removal from healthcare facilities, except bar of soap for individual patient use); faucets and sinks (Ehrenkranz and Alfonso, 1991); removing contaminated personal protective equipment such as gloves, aprons and masks; and the presence of rings, which can cause the skin below the ring to be colonized by gram-negative bacteria, normally found as transient skin flora (Hoffman et al., 1985).

Surgical hand antisepsis

Therefore, hand washing only makes the hands socially clean and does not remove deep-rooted skin flora.

Alcohol hand rubs

It is important that healthcare professionals understand that hand washing and the use of alcohol hand rubs and gels are equally important and that there is a place for both within the patient care arena.

Hand decontamination at the point of care – the 5 Moments for Hand Hygiene

Moments for Hand Hygiene

Slips, trips and falls resulting from product spills, accidental and/or deliberate ingestion and cases where hand rub or gel had been splashed into the eyes prompted the NPSA to issue another patient safety alert, redirecting the attention of healthcare staff and the public to hand hygiene at the point of care and requires hospitals and other organizations to conduct audits and risk assessments in relation to product placement. It was clear that although the profile of hand hygiene had been raised, it was still not being undertaken at the most appropriate opportunity and attention needed to be focused on improving hand hygiene compliance at the point of care, leading to the national adoption of the 5 Moments approach.

Moments

To protect the patient from harmful germs, including the patient's own, from entering his/her body. After touching the patient and his/her immediate surroundings, clean your hands when you leave the patient's side.

The patient zone

Transmission of infection from the environment can occur due to the variety of microorganisms that can be found there (environmental microorganisms and those excreted from patients). The immediate patient environment (known in 5 Moments as the patient zone) will be heavily contaminated with microorganisms from the patient.

The healthcare zone