Subject Background

Illness and Disease

The sufferer experiences the "introduction" of the disease into their life through various physical sensations and emotional consequences. The recognition and interpretation of different but important variables by patients and providers influences the concept of the disease and the approach to the self-care activities of the patient.

The Challenge of Diabetes

Self-care requires that these variables are constantly monitored and self-care practices maintained with precision to avoid potentially catastrophic consequences (Turner and Kelly 2000, Okken et al, 2008). To safely and reliably care for themselves, people with diabetes construct an internalized understanding of their physical condition as it relates to their social and emotional realities and personal values.

Patient Activities as Patient Adherence

In the bystander role, the socially appropriate behavior is to follow the instructions of the officer. This is the kind of thing that will happen quite often in the middle of the night for a good time.

Theoretical Background

Narrative Theory

Narratives in Praxis

Healthcare Narratives

Sensemaking

Sensemaking as a Theoretical Perspective

Sensemaking as a Process

Sensemaking and Common Sense

Sensemaking and Health

Sensemaking and Narrative

Methods

Data Collection

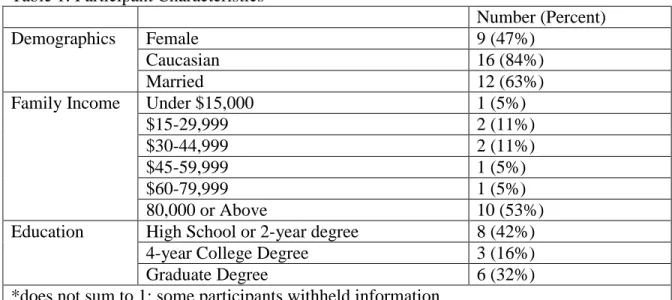

Selection criteria required participants to use a sliding scale for their insulin, which required them to calculate the amount of insulin required for each administration, rather than a fixed insulin dose. Trained research assistants conducted the interviews in the participant's home using an open-ended interview guide. The interview guide explored the participant's health routine, including how and why the participant constructed their routine in the specific way.

The interview was not intended to compare participants' health actions with their provider's recommendations or to assess the 'correctness' of participants' thought process. Audio recordings of the interviews were transcribed and analyzed in Dedoose, a qualitative software program (Version 7.6.21; Sociocultural Research Consultants LLC, 2017). The selection criteria for the final data set excluded any interviews not conducted by the author.

Data Analysis and Reporting

Well, my life has changed a lot…but I wouldn't necessarily say it's because of the diabetes or the treatment. For respondents, diabetic actions are often not extraordinary or particularly unique actions, but regular, normal activities that they perform in the course of the day. Michelle's story begins with an initial mental model of the relationships between diet, insulin and sleep.

By narrating their experiences (imposing a structure and meaning) participants can efficiently recall the sequence of events, the inferred character of relationships between all the variables and the meaning of the experience. Therefore, a large part of the self-care process included determining when and how to share stories publicly. The participants therefore discussed the evaluation of the 'value' of their stories (explanations) against the 'value'. of the acceptance as evaluated by others.

You know, I think that was kind of one of the problems I had when I was there with him. in the clinic it was because I am willing to give, but you must be willing to meet me somewhere halfway….

Results: the Sensemaking Framework Content of Narratives

Participant Narratives as Medium to Communicate Perspective

Insulin used to be from pigs and cows and then it changed to human insulin and then I noticed that the blood sugar would drop so much faster with this type of insulin and I would often have lows in the middle of the night and it scared me. After a series of nocturnal lows, Michelle faced an ambiguous event: her interpretation of the relationships was either inadequate or incorrect, and actions based on this model yielded surprising and negative results. And one of the managers looked at me and said, "Turn off your phone."

Narratives that communicated acceptance of the biomedical model often came from participants who had little other interaction with biomedical institutions. In telling this story, James indicated not only that he agreed with the medical explanation of diabetes, but that he and the provider shared the same meaningful patterns: they both emphasize. values of similar variables and interprets the relationship of variables in similar ways. Because of the imbalance of social power in the patient-practitioner relationship, participants turned to narratives as a resource to defend their actions or confirm their own understanding.

Using meaning theory to aid understanding of the recognition, assessment and management of pain in patients with dementia in acute hospital settings.

Narratives Communicating Implied Relationships

Narratives Communicating Explicit Relationships

Colin's method of controlling his glucose level is extremely difficult, but because he found it results in somewhat more stable glucose levels, it would not show up in any of the routine medical tests. Sunday night we went to my nephew's birthday party and I thought I had everything figured out and I came home and I was like, "I don't feel so good." And I checked my blood sugar and it was 422. Because others were involved in earlier sensemaking processes, they could also help identify unusual situations and possible problems, as well as help solve problems quickly because they have a fundamental 'role' and a common understanding.

And first they said, "Oh, yeah, you're on the cutting edge, we really are, you're in a field that we really like." And then I get a call: “I saw you're diabetic. So now you [the doctor] will ask me to carry a needle and a pen or a needle and a vial. I deal with, work with mine; my mother is already a diabetic. for a long time, so I was already familiar with nutritional needs and things like that... and she was talking about lifestyle changes, and I don't think my lifestyle can change too much.

So while he didn't feel the need to purposefully change the GP's mind - he had the income to buy his strips outside the insurance mandates - deeply embedded medical surveillance practices prevented him from performing the act without the GP "finding out".

Explanatory Narratives: Sensemaking Origins

Explanatory Narratives: Sensemaking and Personal Values

So it's not just me to worry about, but I have to worry about four or five other people... You know I could, it's just, it's really a shot in the dark. You might know because you have high blood sugar, but you're just telling yourself it's not the insulin pump. People say] "You can do whatever you want." No, it sounds good, but it's not true.

But when you treat it, and you're like, ok, ok, I'm sweating and I'm crying, and I'm nervous, but I've got apple juice here, so I know I'm going to be fine, and the next morning you wake up and you're like it seems no one can take this seriously. You know if they see you going through every day and you're not complaining about your diabetes - which is good you don't want to dwell on it all the time because, you know, you're normal - but your normal isn't Don't even tell the times of bad. Having no other previous information about diabetes awareness, he spent many hours researching the medical literature to learn about the condition. when I'm at the doctors and we're talking about something, I kind of know what they're talking about and plus they know that I kind of know.

I think they are not realistic when they start talking about lifestyle changes, choices, because they don't look at it.

Results: Use of Narratives in Self-Care Activities

Narratives as Tools in Self-care

Participants used stories of previous experiences to explain their current system of health-related actions. The stories were moments of meaning and therefore highlighted the complex, interconnected relationships between the domains of life valued by the participants. Narratives, then, are concentrated packages of information that implicitly and unconsciously demonstrate their ways of knowing, linking their inferred relationships between their body and illness, their values and beliefs, and physical and social structures.

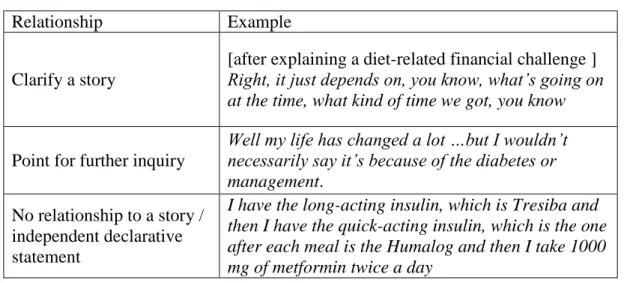

By packaging past experiences in a story form, participants can also share the information in a concise and familiar format. In other words, stories are repositories of information that provide an efficient method of remembering and communicating highly complex concepts. After sharing a story with the interviewer, participants often noted other times they had shared their stories.

Narratives to Facilitate Shared Sensemaking

Narratives as Benchmarks

Narratives to Elicit Cooperation

However, unlike when she was pregnant, she was unable to convince her co-workers that it was important to recognize when they were potentially contagious. In these cases, the narrator had to navigate gaining acceptance for non-normative activities with the possibility of being banned from involvement. I mean I think I can deal with my supervisor, but I wish I had more time to, you know, okay, I can check my blood sugar, you know, and here's 5 more minutes, but then, I wouldn't want the , the, the, you know, okay, well he, why does he do that, you know.

As shown, when the storyteller felt that the story would provide insufficient means to secure help or that it would harm others' interpretations of them, the storyteller withheld or hid the story. While the stories are valid and the reality the storyteller may want to share, he is aware that the listener may recognize and evaluate the story differently. But when you get down to it and you're like, okay, okay, I'm sweating and I'm crying and I'm nervous, but here I have apple juice so I know I'm going to be okay, and the next morning you wake up and you're quote-okay- is similar.

And you don't want people to think "oh, she's got severe diabetes, she has no control over it.".

Narratives to Engage with the Medical Institution

And the realization of it. at any moment that could have turned into an emergency or a life-threatening situation. And you don't want people thinking "oh, she's a bad diabetic, she has no control over this." interpret similar variable values and the relationship of the variables in similar ways. A lot of places I lock it up in my truck or whatever because, especially because I'm out to see kids and I'm out to see other people, and some of these houses I don't want to bring anything in….

And some of them have their own, you know, they have drug problems and things like that. By emphasizing lifestyle changes, Janice felt that her doctor ignored how important her job was to her by insinuating that it was something that was easy to change, while devaluing Janice's diabetes knowledge by restating health information that Janice already known. When Flexible Routines Meet Flexible Technologies: Affordability, Constraint, and the Interference of Human and Material Agency”.

When Protocols Fail: Technical Evaluation, Biomedical Knowledge, and the Social Production of "Facts" About the Telemedicine Clinic.

Discussion

Discussion

People with type I diabetes recognize that their self-care needs affect the way they interact with non-biological variables such as time and activities, and this interaction can sometimes be difficult to transfer to co-workers, friends and partners. In both situations, stories are used as an effective and accessible means of conveying interpretations of complex relationships.

Future Directions