Since growth rates are determined not by absolute but by relative levels of human capital (receiver and provider of information), this model predicts a wide variety of economic performance among underdeveloped countries. If higher human capital means a higher probability of solving problems, as I assume in this paper, then it is the level of human capital that determines how well a country can exploit information spillovers. Finally, notice that it is the similarity of countries' human capital that determines how valuable a country's information is, which in turn determines their rates of technological growth.

Therefore, this article predicts that the simple relationship between growth rate and the 'absolute' level of human capital could be highly non-linear. Before I dive into the sales representative optimization problem, I want to highlight the role of human capital in this article. Similar to the idea of Nelson and Phelps (1966) and Romer (1990), human capital in this model enters the production function by facilitating technological progress.

Unlike some models5, this kind of setting implies that it is the level, not the growth, of human capital that enters growth accounting. A popular argument behind it is to increase social returns to scale in building human capital. In the previous section, I showed that countries with higher human capital level tend to enjoy both higher per capita income level and higher growth rate.

For country i, the most valuable information is obtained from countries with a similar level of human capital, since it is very possible that country i can solve these problems as well.

Two Countries

In Section 3.2, I show what would happen in the case where there are more than two countries in the world. Suppose there are N countries in the world and they are ordered according to the knowledge sets of their representatives, K1 ¾K2 ¾ ¢ ¢ ¢ ¾KN: This also implies S1 > S2 >¢¢¢> SN: Let ©it ½© be the set of of problems that have been tried by the country before the end of the date and between them, let ©¤it ½© be the set of those that have been solved. The main assumption about the history of the spread of information is thatKi;©it;©¤it; 8i are known to every country.

Let It =ffSigNi=1;f©itgNi=1;f©¤itgNi=1g be the set of information available to all states at the end of date t.9 10 We can also define Djit ´©¤itn©jt to be a set of problems , which were solved by country i, but not attempted by country j. Let ^v®(A;S2) be the maximum expected discounted utility when the technology level is A after information is available. Note that S¤¤ is the critical value for ^S2: the minimum capacity for state 2 in information spillover is.

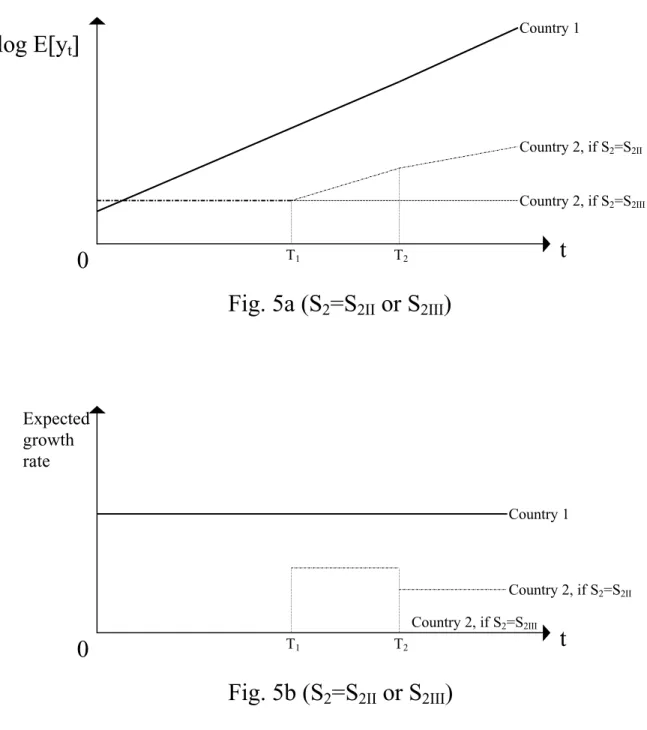

Apparently, the information in D21¢ is "consumed" by country 2 at a faster rate than it is replenished. Therefore, sooner or later country 2 will use up all the valuable information from country 1's experience. However, the minimum capacity for place 2 to grow ( ^S) is still right from the similar argument as the following one (5).

After T2, if country 2 does not try to solve problems before T1 (S2 < S¤), then it will only do problem solving when it has new valid information. At this point, I will ignore the strategic concern and focus only on what are the expected growth rates for both countries in the case of mutual information spillover. Applying these results, we can obtain the expected growth rates for both countries after T2.

For state 2, when S1 rises, the two effects work in opposite directions. The beneficial effect is that country 2 can now benefit from country 1 more often, as the possibility of country 1 generating valuable information is greater. The detrimental effect is that information becomes less valuable because the gap between their human capital levels widens.

Multiple Countries

One might think that as global technology becomes more and more advanced, poor countries today would need to attain higher levels of human capital to break out of the low equilibrium. In other words, the human capital threshold becomes lower for countries where growth has started. Some researchers emphasize that sometimes the only way a person can build their human capital is by actually doing the work (that is, by learning by doing).

This model suggests that, in order to enjoy a high rate of growth in technology, countries should trade with those countries with slightly higher human capital.17. Although this model predicts that the learning curve will depend on the human capital levels of producers, since their human capital is assumed to be exogenously given, they actually do not. One interpretation is that this group is large because the level of human capital of country j is much lower than that of country j.

Another interpretation is, although the difference between their human capital levels is small, there just hasn't been enough time for country j to improve its productivity due to, perhaps, historical reasons. Furthermore, this model implies an appropriate concept for technology gap in the context of productivity growth should be between the receiving country and the country that provides, not the world. In section 3, it is assumed that countries with a human capital level higher than the threshold (S¤) solve new problems when there is no valuable information available.

Suppose there are only two countries, a possible Nash equilibrium is that one country is always trying to solve new problems and the other country is always waiting for new information, and the former country is not necessarily the one with higher level of human capital. How strong this effect is, and hence how fast a country can grow, will depend on the relative human capital levels of the countries receiving and supplying information. It is not always best to use information from the most advanced country, and countries in the middle group play an important role in the world economy.

In the long run, countries' levels of technology and living standards are still ranked by their levels of human capital. The benefit from receiving an additional amount of human capital is high for countries that have good information. Therefore, if marginal cost does not depend on levels of human capital, countries that expect rapid growth, albeit in the short run, will have a higher incentive to accumulate human capital.

This implies that in the long run we can observe multiple groups,20 and that countries within each group have the same level of human capital. Proving this conjecture certainly requires a formal model that endogenizes human capital accumulation, and I leave that to future research. He concludes that countries in the world tend to cluster into two extreme groups (rich and poor).

Then the expected growth rate for each country is fair. 1999), \Threshold Human Capital As a Precondition of Economic Growth", manuscript. 1991), Innovation and Growth in the Global Economy (Cambridge MA: MIT Press). 1981), Research on Productivity Growth and Productivity Di®erences:.