The last section of the book, Section IV, contains six case studies on the topic of information management in higher education. Jennifer Croissant of the University of Arizona for allowing me to participate in a seminar they co-taught for the Center for the Study of Higher Education in the spring of 2003 on the topic of knowledge management in higher education.

The Political Economy of Knowledge

Management in Higher Education

Abstract

The purpose of the chapter is to provide a foundation for the rest of the book and the more specific studies of KM in higher education that will follow.

Introduction

KM proponents have noted that the absence of KM principles in higher education is a striking omission (Serban & Luan, 2002). This book offers an alternative expression of ideas and case study evidence to encourage a more thorough exploration of the use of KM in higher education.

The Economics of Knowledge Management

However, academic managers using KM techniques need not adopt corporate values that promote the commoditization of knowledge for profit. For these reasons, we need to begin to understand how market principles influence the implementation of knowledge management in the public arena.

Academic Capitalism

The theory of academic capitalism was further developed by Slaughter and Rhoades (2004), who argued that the shift towards market-like behavior in academia is an outgrowth of the new economy. Interestingly, the interpersonal and interorganizational networks noted by Slaughter and Rhoades are enhanced by information and communication technologies.

Academic Managerialism

In the academic arena, the new social and technical division of labor described by Castells can be most easily observed in the teaching function, where information and communication technologies have greatly affected the production cycle. In fact, the faculty's teaching mandate is being undermined by the proliferation of the “management experts” described by Rhoades and Sborn.

Digital Capitalism

However, it is important that academic managers fully understand the changes that have taken place in higher education regarding the division of labor and production functions. Although research universities were central to the early stages of the Internet, Schiller does not fully explain the role of such institutions from the 1970s onwards.

The Politics of Knowledge Management

Yet Castells showed us the essence of working in a knowledge factory in a knowledge age when he said that "in the new, informational mode of development, the source of productivity lies in the technology of knowledge generation, information processing and symbol communication." (Castells, 2000, p. 17). He further clarified this idea by saying that "what is specific to the information mode of development is the action of knowledge upon knowledge itself as the main source of productivity".

Digital Democracy

In circumstances where such campus-wide software is purchased, some degree of control over academic information management is transferred to the private sector. There are even campuses where IT management is performed by employees of the enterprise software suppliers.

Globalization

The mixing of public and private managers in these situations complicates the flow of information in higher education organizations, since the work processes themselves are seen as proprietary information and are therefore subject to classification as. For example, if Mexican higher education institutions purchase curricula developed in Canada or the United States, does this perpetuate the political and economic dominance that has already made North America an unbalanced trading region.

The Sociology of

Knowledge Management

Social Construction of Technology

It acknowledges that many individuals are involved in the development of technological solutions and also highlights the consequences if key actors remain outside the development process. Forsythe describes the development and implementation of a digital solution to the problem of tedious patient history taking during a doctor's office visit.

Conclusion

Or how sociology of science and sociology of technology can benefit each other. Pinch (ed.), The social construction of technological systems: New direction in the sociology and history of technology (pp. 17-50).

Knowledge

Management Trends

Challenges and Opportunities for Educational Institutions

However, educational institutions may be able to learn from knowledge management efforts in the business sector in terms of the limitations and shortcomings associated with knowledge management. Furthermore, recent trends in this field also do not fully distinguish between data, information and knowledge (Huysman & de Wit, 2002).

Concepts and Theories

This chapter illustrates how KM strategies and practices enable higher education institutions to differentiate between data, information, knowledge and action and how this iterative cycle can help organizations assess their available resources – that is, their people and processes together with their technology. Therefore, developing policies and processes that fundamentally support and organizationally align information sharing activities is one of the first steps an organization must take to embrace and develop successful KM strategies.

People, Processes, and Technology

Instead, technology is just as important as the ability to influence how information flows through an organization. For some, KM is used as a phrase to describe the technology used to manage an organization's data, such as data on monthly sales figures or a database of successful sales strategies.

Data–Information–Knowledge–Action

An organization that fully adopts KM strategies and practices also demonstrates activities within each component of the KM cycle simultaneously. Engaging in the knowledge stage of the KM cycle also includes individuals engaging in data and information activities.

Current Challenges for KM in Higher Education

Information technologies and applications are only gradually improving an organization's ability to facilitate the exchange of data and information. As such, improved methods of data and information sharing need to be linked to embedded and long-term knowledge management strategies to address organizational-level factors that may hinder or promote an ongoing culture of inquiry, reflexivity, and long-term organization. - tional learning.

Opportunities for KM in Education

KM requires educational institutions to candidly address their current patterns and processes, and only from this position begin to capitalize on the opportunities that KM strategies and practices can provide. This process of organizational re-evaluation and reflexivity appears to be the most difficult challenge for educational institutions.

Opportunities for Continuous Learning

KM practices can help bring these two together, that is, aligning institutional capabilities and resources to better address student needs and thus student success. Consequently, educational institutions that engage in KM practices for continuous learning at the organizational level are also involved in promoting continuous learning for their students.

Ontologies in

Higher Education

This chapter provides an introduction to the use of ontologies and taxonomies in higher education. After a brief introduction to the nature of ontology, examples of ontology in higher education are reviewed.

The Nature of Ontology

Higher education often sees itself as such a complex enterprise that it cannot be classified, classified, or pigeonholed” (1997, p. 23). However, there is a long history of major classification schemes in higher education, including those of the US National Center for Higher Education Management Systems (NCHEMS).

The Marketplace of Institutions

As a result of this effort, a new taxonomy for the market was created and “the idea and structure of the taxonomy resonated intuitively” with institutional leaders (Anonymous, 2001, p. 53). However, as Grasel (1999) explains in Reality of brands: Toward an ontology of marketing, “the ontology of marketing, particularly the question of what products and brands are, is still largely unexplored” (p. 1).

Academic Disciplines

These codes were updated to six-digit CIP codes in 1985, with a "taxonomic coding scheme for secondary and post-secondary instructional programs" (NCES, 2004a, p. 1). For internal use, most colleges and universities align their departments with NCES reporting requirements using CIP codes.

Documentation of Data

Another national effort to promote effective data practices is that of the National Postsecondary Education Cooperative (NPEC). ANSWERS is no longer available online as part of the NPEC website, but is maintained by the developer at http://.

Learning Management Systems (LMS)

Learning object metadata (LOM) is used to define a “base schema that defines a hierarchy of data elements for learning object metadata” (Ogbuji, 2003, p. 1). Relationship: “characteristics that define the relationship between the learning object and other related learning objects”.

The Higher Education Enterprise

These require complex taxonomies and new types of search engines that combine the best features of search and classification.

Online Resources

Issues in Creating Taxonomies

Search Retrieval and Content Management

Creating Ontologies

An online tool called the SUMO Browser is available to help users navigate and use SUMO.

Software Solutions

For example, the terms 'IPO' and 'preferred customer', which appear in separate but related documents, have little clear connection to each other” (Delphi Group, 2002, p. 3). Based on work done at Xerox, the Inxight SmartDiscovery software tool "automates the creation of structure on otherwise unstructured data sources by leveraging more than 20 years of research in natural language processing and data visualization techniques" (Inxight, 2004, p. 2) .

Problems and Issues in Maintaining Taxonomies

Other software, such as The Texis Categorizer, “assigns documents to categories in a taxonomy and automatically attaches subject codes and other metadata after being trained on sample documents.” There must be a “tight and interactive relationship between categorization and retrieval” (Lamont, 2003, p. 6). According to the authors, collaborative thinking about ontology should be a non-competitive environment.

Concept Maps

Leake, et al (2003) explain that concept maps are similar to "vector space models" in the way knowledge is represented. However, there are limitations to the results, and other researchers have created software such as EXTENDER (Extensive Topic Extender from New Data Exploring Relations) that “identifies and suggests new topics” (Leake et al., 2003).

Specific Issues in Taxonomies for Higher Education

It is the author's experience that the choice of categories is often a political process, focused less on usability and the needs of a majority of users than on the images and perceptions the institution wants to promote as its public 'face'. In Milam's study of the 'politics of websites', the conclusion emerged that CWIS is a form of sense-making, more focused on ambitious ideas than on reality (Milam, 1998). The evolution of the taxonomy has stalled due to the amount of effort required to maintain it correctly.

Future Trends

Retrieved October 26, 2004, from http://www.km world.com/publications/magazine/index.cfm?action= readart icle. Retrieved October 26, 2004, from http://www.ksl.stan ford.edu/people/dlm/papers/on-tology-tutorial-noy-mcguinness-abstract.html.

Toward Technological Bloat and Academic

Technocracy

The Information Age and Higher Education

This chapter explores the impact of one aspect of the information age: the increased use of computers and computer-mediated communication in higher education institutions. Next, the theory of technocracy is identified, discussed and related to higher education and the use of information technology.

Conceptual Frameworks

We find academic capitalism to be a particularly useful theoretical framework for understanding the trend towards the use of information technology in higher education, particularly in student affairs. In the US, experts are mostly white and male, non-experts are often non-white and/or female.

Discussion of Issues

Restructuring Higher Education with Technology

Workstations do not get tenure, and delegations are less likely to wait for the provost when certain items of equipment are "dismissed". "Retraining" IT equipment (for example, reprogramming), although not cheap, is easier and more predictable than retraining a tenured professor. Massy and Zemsky (1995) listed economies of scale as one of the benefits of the introduction of IT into higher education.

Technology and Efficiency in Higher Education

While technology can augment this process, to force technology upon this institutional unit is to force a philosophical shift in the mission of the student affairs profession (Moneta, 1997). However, it may be that the goals of student affairs are not included in the information systems as student services professionals are not fully involved in the design process (Barratt, 2001).

Technological Bloat

The cost of implementing and maintaining the new technology in higher education can similarly be hidden in the budgets of institutions. Both academics and practitioners need to pay more attention to the major changes impending in higher education as a result of the increasing role of computers and computer-based communications.

We’ve Got a Job to Do – Eventually

A Study of Knowledge Management Fatigue Syndrome

These are just two examples of the problems universities face when implementing knowledge management systems. This chapter discusses how such a long-term project has affected the units of the university directly involved in the first rounds of implementation, how users have reacted to the system, and how the overall structure of units has changed.

Conceptual Framework

Over-competition in a potentially profitable market defines Hakken's (2003) technical explanation for the knowledge management fatigue syndrome. Once again, this technical explanation for the knowledge management fatigue syndrome also relates to Birnbaum's (2000) conception of higher education management fads.

Data and Methods

Analysis

The bulletin does not refer to the RFP, which called for full implementation by December of last year, let alone the original 1994 plan. As of the summer of 2004, the project had finally implemented the first of its major modules. , but he had not yet completed full implementation.

Technical Explanantions

All three partnerships were critical in the initial development of the student information system project at Southwestern University. However, as predicted by Hakken (2003), none of these partners really had experience in meeting the exact needs of the university.

Conceptual Explanation

First, can Hakken's (2003) concept of knowledge management fatigue syndrome be used to analyze and understand the implementation of a student information system at Southwest University. And does the introduction of the system show evidence of technological bloat and academic technocracy.

Institutional Research (IR) Meets Knowledge

Management (KM)

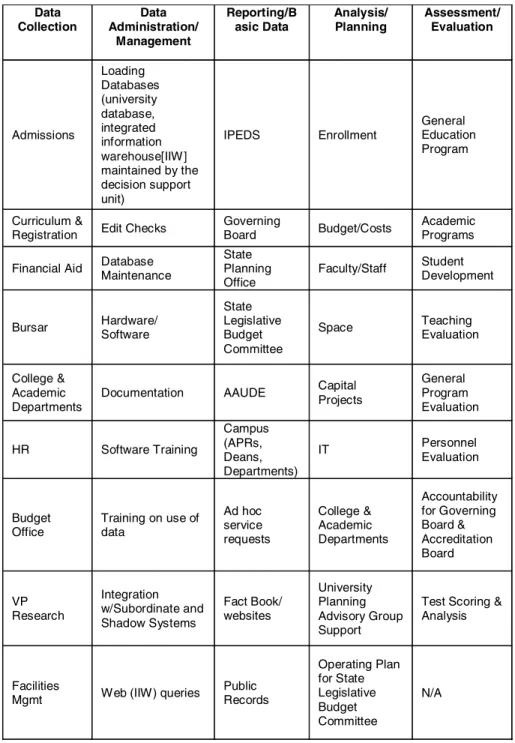

Due to increasing competition and the formation of the field of knowledge management (KM) in the early 1990s, universities have moved in a direction that embraces the cumulative endowment of knowledge held by universities. In order to remain competitive and strategically contend with market forces, universities are involved in this rapidly evolving field of knowledge management in several areas: human resources, organizational development, change management, information technology, brand and reputation management, performance measurement, and evaluation. (Bukowitz & Williams, 1999).

Literature Review

As the young and popular field of knowledge management continues to emerge, some universities will succeed in aligning their organizational activities with KM principles, while others will not; others will only accept parts of the KM framework. This means that they will spend large sums of money building system database repositories and investing in the people who support such systems, but they will not invest commensurately in the human capital needed to interpret the information generated from these systems to advise decision makers.

Institutional Research (IR)

KM Overview

IR Meets KM

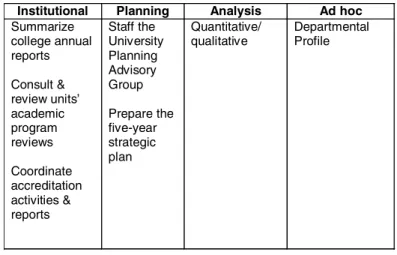

She argues that “in a knowledge management environment these four facets persist; however, they converge in a broader, more integrated dimension – the fifth face of institutional research – IR as knowledge manager” (Serban, 2002, p. 105) (see Table 1). The planning unit was managed by a coordinator who also reported to the senior administrator in the academic business area.

Findings

IR as a Fragmented University Function

The author positioned himself as a participant observer in some of the data collection and analysis, providing valuable access to information. In June 2003, the university president and provost created the new DAPST and assigned the newly appointed chief information officer (CIO) to chair the team.

The Proceedings

According to the president's letter of invitation to prospective DAPST members, "the fundamental purpose behind this study is to improve the University's ability to bring data and analysis relevant to management decisions." In the same document it was stated that "administration is more and more related to assessment and projection, both of which are completely dependent on the quality of the data we collect and the analysis we do on the data". The Chairperson also found it necessary to illustrate a significant example where IR had failed. The Realignment Initiative exercises were largely supported by such non-comparative narrative data as Academic Program Reviews and constituent testimony.” Clearly, the chair suggested that one of the units, if not all, did not successfully coordinate this effort in order to provide the best possible information to inform decision-making for such a high-level management initiative.

Digging In

This person believed that “the lack of understanding, coordination and collaboration for data, analysis and planning from a systems perspective is a key piece of the puzzle for our suboptimal performance in these critical areas. The director of the decision support unit highlighted the most important achievement of his unit - the Integrated Information Warehouse (IIW).

The Elusive Final Report

Noticeably absent from the report was any analysis of data examining the veracity of the products that the respective IR entities under investigation stated they provided, and furthermore the quality of such products. Furthermore, the report made no recommendations for reorganization of the units examined.

Study Team & Its Findings: Do KM Principles and Practices Emerge?

One person was a key architect for IIW in the Decision and Planning Support Unit and the other was the administrator of UIS. In addition, the former director and two systems support personnel from the Decision and Planning Unit were reassigned to work with IIW.

Recommendations

That is, Western spent much of its energy discussing how to improve its data, data quality, and data access, and invested in the people who support such systems, but failed to invest appropriately in the human capital that was necessary to transform the generated information. from these systems to knowledge to advise decision makers. DAPST and its draft report illustrate that KM principles were not at the core of its values.

Endnotes

Revealing Unseen Organizations in

A Study Framework and Application Example

In the higher education environment, changes in management practices, organizational structure, and communication technologies have sparked much speculation about the future of academic institutions. I use a structural perspective on technology (Orlikowski, 2000; Poole & DeSanctis, 1990) as well as a classical understanding of HE structure (Clark, 1986) to support my investigation of the MIT system.

Background

I begin my discussion of the MIT system by laying the theoretical foundations necessary to consider their CM system as an organizational and social phenomenon. I conclude that MIT technologies not only have the potential to reclaim familiar forms of HE, but they can also create new, contested forms.

Technology as Message Transmission Tool

The ontological assumptions that form the basis of the technology-as-tool perspective are rarely explored. The technology-as-tools view views CM system participants as tool carriers, using inert electronic instruments to meet their information transfer needs.

Technology as Social Process

Analyzing these assumptions reveals that the message transmission perspective rests on the notion that it is possible to separate technology from its social context (Jackson, 1996). In sum, separating technology from its social context encourages stakeholders to understand CM systems as mechanical tools that transmit messages in an impartial manner.

Different Perspectives, Different Lines of Inquiry

In his view, no structures—technological or otherwise—exist by themselves. By highlighting social interaction, the technology-as-social-process perspective puts a "face" on previously inert "technical" issues and emphasizes that people are central to the organization of technological structures - and they organize them in the context of specific social framework.

Issues, Controversies, Problems

Unfortunately, few of us know how to approach these conversations from a more inclusive and more productive point of view. It is my hope that greater attention to the social nature of CM systems and more diverse participation in future discussions will increase the likelihood of valuable and equitable HE structures for tomorrow.

Solutions and Recommendations

Combining Orlikowski's considerations of structure with Clark's dimensions of organization produces a hybrid analytical framework. Using this framework for my analysis of MIT's CM system, I first discuss the potential structural properties related to the technology and illuminate them by examining Clark's three structural dimensions of higher education organization.

Case-Study Application: Part 1

The Potential Structural Properties of HE’s Knowledge-Based Work

Normative Rules as Potential Structural Properties

Authoritative Rules as Potential Structuring Properties

Clark asserts, "bureaucratic, political, and oligarchic forms of national authority contribute to the integration of the whole" (Clark, 1983, p. 136). The cross-national comparison that Clark provides facilitates a clearer understanding of potential US structures.

The Disorderly Nature of HE Order

She writes: "In the US, several states have implemented policies designed to regulate academic quality, and debates in the federal government that led to the creation of State Postsecondary Review Entities (SPRES) have been characterized as the inauguration of a new era of government control" (Sporn, p. 11).

Underlying Infrastructure as Potential Structuring Properties

Application: Part 2

Moving from Potential Structural Elements to Technologies-in-Practice

Overview of MIT’s CM System

The ultimate goal is to make the OKI platform publicly available to those who want and have the skills to customize their proprietary learning management systems. For those who do not have such a system or the necessary skills to adapt it, MIT (and others) plan to "package their open source systems" (Tech talks, CM SYSTEMS, p. 13) and license them to interested institutions .

Enactment of Knowledge-Based Work Structures

While, according to their description, MIT's OCW is one of many possible applications supported by OKI, it is nevertheless receiving considerable attention from those interested in MIT-led efforts. It is one of three pilot models being developed in conjunction with the underlying architecture of OKI's larger training infrastructure, all of which are being closely studied as potential training models.

Discipline Structures

To talk about knowledge-based work, beliefs and authority as separate structuring elements is artificial and at times a little awkward, but at the same time useful for analytical purposes. I explore these questions – often raising more questions than I answer – in the following three sections: knowledge-based work structures, normative structures and authoritative structures.

Enterprise Structures

Enactment of Normative Structures

First, I focused on analyzing the separation of discipline culture from corporate culture in MIT's technological establishment. Three of these goals ring true to the traditional values of the profession's culture – open, reliable and flexible.

Enactment of Authority Structures

Before we explore that question, however, it's helpful to wrap up my analysis of MIT's CM system by looking at the authority structures put in place in the collaborative effort. the Service Interface Definitions or OSIDs) and the second for the "implementations and sample applications" associated with the OKI project. Given this fact, it seems important to see who exactly participates in the design of this infrastructure.

Implications

In the case of MIT's system, using a structuration framework for analysis reveals how the CM system potentially influences and is influenced by the social organizations of HE. It largely depends on members of the HE community: “...the success of OKI depends almost entirely on the support it receives.

Distributed Learning Objects

An Open Knowledge Management Model

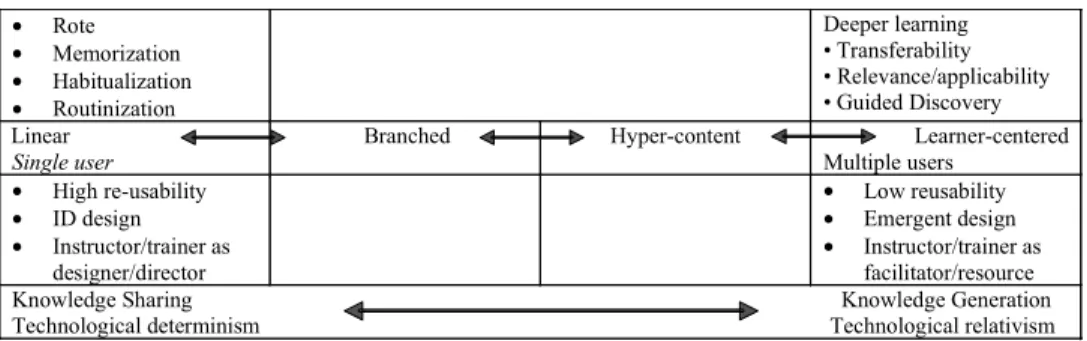

Learning objects must be reusable and repurposed across time and location and interoperable across systems and software (see Downes, 2002; Robson, 2001; Wiley, 2000). This chapter analyzes the emergence of learning objects as a dynamic and interactive relationship between technology and the organization.

A Starting Point

We discuss four current models of knowledge management found in higher education: the traditional model, the intellectual capital/appropriating model, the sharing/reciprocal model, and the contribution pedagogy model. We propose a new, relativistic model of knowledge management for higher education that accommodates cross-institutional cultures and beliefs about learning technologies, construction of knowledge across systems and institutions, as well as the trend towards learner-centred, disaggregated and re-aggregated learning objects, and negotiated intellectual property rights.

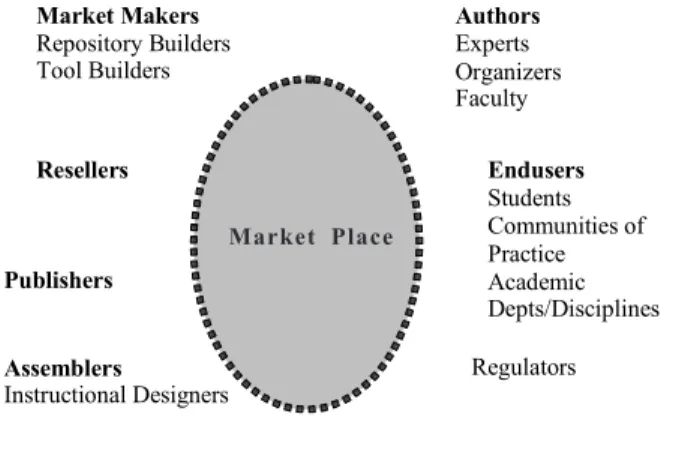

Thomas’s Theory of Organizational Technology

From these processes, via a constructed technological system, emerges a learning object economy2, which includes various constituents: the 21st century learner, the subject expert (university professor), suppliers who support or enable knowledge management, and populations who harvest and benefit from the collection of knowledge. We believe that these are just some of the local and global changes taking place that are motivating higher education to explore a system of knowledge management that is socially constructed rather than organizationally determined.

Social Construction of Knowledge and Learning Objects

Dissemination "refers to the human processes and technical infrastructure that make embodied knowledge, such as documents, available to the people using the documents and knowledge bodies" (p.6) that serve a function to achieve organizational goals. However, such changes must be communicated to the population using the knowledge.

Technology-Supported Knowledge Acquisition and Construction in Higher Education

The nature of course construction and reuse as disaggregated5 course content that can be recombined in various ways reflects current thinking about the social construction of knowledge advocated by pedagogical models of online learning (Simonson, Smaldino, Albright, & Zvacek, 2003). ), the commodification of the course (Diaz, 2004) and the instructional use of learning objects (Higgs, Meredith, & Hand, 2003). This is an opportunity to create knowledge that informs the social model of knowledge management through knowledge management curricula that operate across institutions, through cross-fertilization, be it intentional (deterministic) or chosen (relativistic).

Transmission of Knowledge Across, Through, and in Spite of Organizations

Technology has changed the nature of traditional learning and training by removing the learner from contexts such as school and the workplace. The "intelligent flexible learning model" is the next-generation model in which the learner accesses learning processes and resources through portals.

Four Models of Knowledge Management

Knowledge sharing and reconstruction with the allocation of intellectual property rights and learner-owner intellectual property rights are necessary in an increasingly globalized and distributed learning ecosystem.7 The Open Knowledge Model embodies trends in a variety of disciplines: computer science (see Table 3. Next offers Bongsug Chae (Kansas State University) and Marshall Scott Poole (Texas A&M University) presented a case titled, “Enterprise System Development in Higher Education.” The authors highlight the challenges educational organizations face when introducing enterprise systems from the corporate sector become

Policy Processes for Technological Change

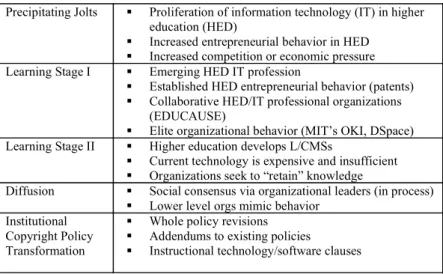

Change in universities is not simply a result of forces acting on universities, but is the result of a complex interaction of internal and external drivers. Technology, in this context, has become the catalyst for change, reacting with other elements in a system to bring about a reaction and a change in form and structure.

Doing the Right Thing and Doing Things Right

The use of telelearning technologies intersects with a large number of social, political and economic factors that are currently influencing university reform. These concerns regarding the implementation of telelearning technologies can be broadly classified as concerns about how to implement these technologies, or "doing things right".

Policy Processes

Drivers for Policy Processes

Strategic Planning

This rapprochement can be achieved by avoiding traditional areas of dissatisfaction and agreeing on a commitment to educational values such as quality, access and responsiveness. He suggests a range of areas where policies could be reformed: recognition of distance education teaching for tenure and promotion purposes, academic tenure requirements and intellectual property.

Strategic Planning for Technology