There has been an expansion of modeling and molecular biology, but little of the latter is still applied to domestic animals. Most farmed animals are fed ad libitum; this means they have food available almost all the time.

Matching Diet with Appetite

Animals normally eat that amount of food that meets their energy needs, including continued fat deposition in the adult. When the amount of grass available for grazing is very scarce and each bite is small, there may not be enough time in the day for the animal to eat enough to meet its nutritional needs.

Definitions

Knowing the concentration of the marker in the food and measuring its concentration in the feces enables the calculation of digestibility. From the tracer content in the sludge, the total sludge production can be calculated.

Classical Theories of Intake Control

The identity of the parts of the brain involved is covered in Chapter 5. There are two main reasons for continuing to study the role of the brain in the control of food intake in domestic animals: On the one hand, there are the agricultural implications of the possibility to manipulate intake by pharmacological or other means to improve animal productivity and welfare.

Prediction of Food Intake

The most comprehensive review of quantitative aspects of food intake with special emphasis on ruminants was conducted by the US National Research Council (NRC, 1987) using data predominantly from North America. The reader is referred to this for more detailed coverage of food intake predictions.

Problems and Pitfalls

The Minimal Total Discomfort Concept of Food Intake and Choice

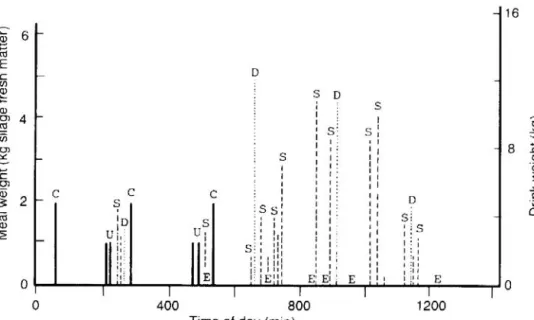

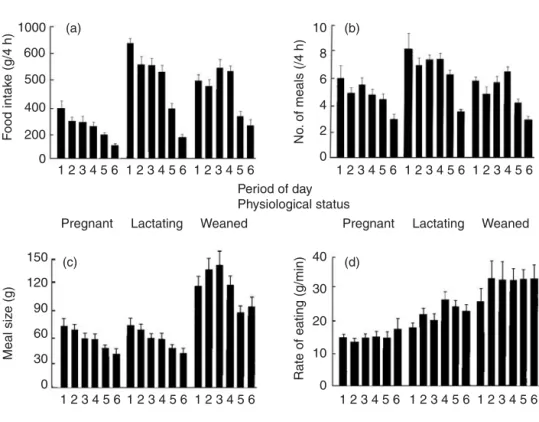

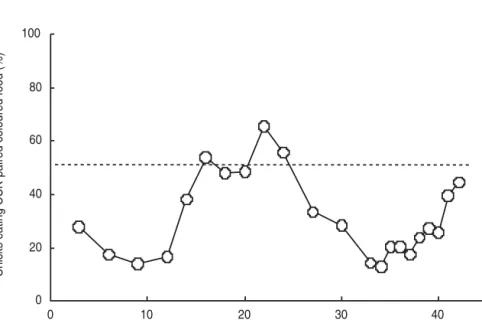

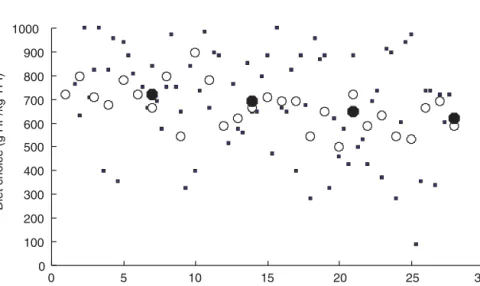

The term "eating behavior" generally refers to mealtime activity in which the time (and weight) of each meal is monitored. An example of this difference between feeding behavior and long-term food intake is shown in Fig.

Monitoring Individual Feeding Behaviour

Eating and chewing time can be monitored by means of a small balloon or a pressure transducer held in the lower jaw of the animal by means of a leash. In the lower part of the figure, the movements of the masticatory jaw can be seen, at low and high resolution, where the latter shows very regular movements compared to the irregularities of eating.

Monitoring Feeding Behaviour in Groups

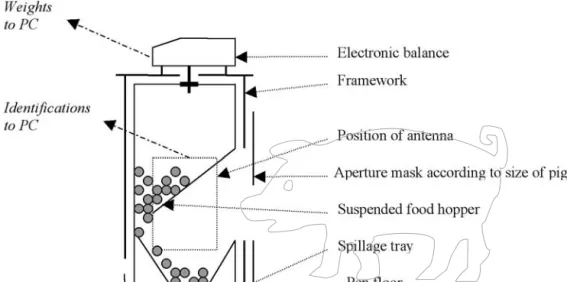

Full details of forage meal patterns by individuals in a group can be monitored by continuous automatic weighing of the box containing the feed, with animals identified as they eat by means of transponders worn on their ear tags or collars. An example is that developed by Forbes et al. (1986), in which cows are collared with commercially available transponders for identification in the milking parlor or at concentrate dispensers outside the parlor.

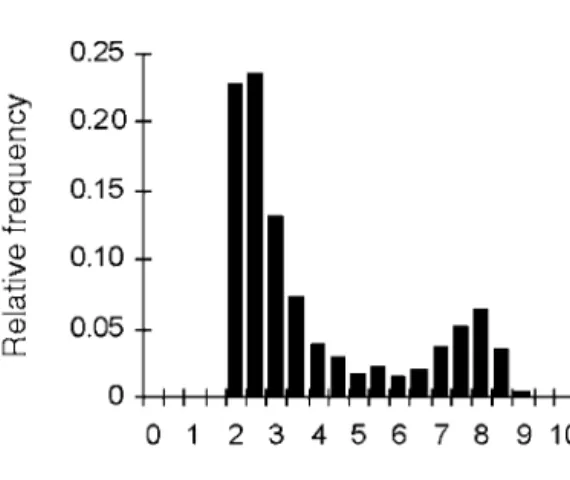

Analysis of Meal Data

For lactating cows fed grass silage on the Leeds University farm, the critical interval between meals was found to be close to 7 minutes (Forbes et al., 1986) and this varied little between animals or with season or the physiological state of the cows. . The three-Gaussian model provided an improved fit to the interval distribution and an estimate of the mid-meal criterion of 2.78 min.

Meal Patterns

It has been suggested that grazing animals are not scavengers because they often seem to spend most of the day eating. To what extent should this be taken into account when determining meal appearance. 2000) analyzed visits to feeders by cows offered two foods with different protein content and those with only access to one of the two foods.

Statistical Analysis of Meal Data

It is therefore important that a method with biological integrity is used for the calculation of intermeal intervals in order not to draw incorrect conclusions from eating behavior data. This is a sign that feeding behavior is governed more by satiety mechanisms than hunger mechanisms, and means that cows regulate their daily intake in ways other than between meals, i.e.

Description of Feeding Behaviour and its Development

The relative smallness of the intervals in the middle of the distribution (between 1 and 20 min) means that changes in the critical interval within this range do not have a very large effect on the calculated number of meals. When outdoors, they spend a lot of time rooting in the soil with their snouts.

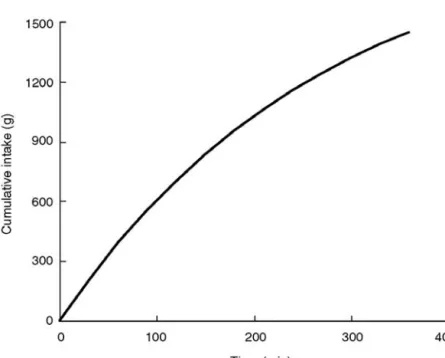

Rate of Eating

The ingestion rate of concentrate is particularly important when the cows are fed in the barn at milking time. During the second and third 30-minute periods, there were progressive reductions in eating rate.

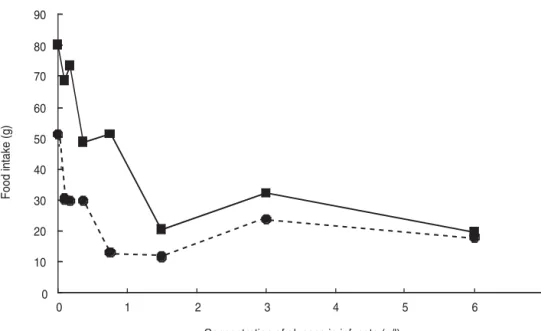

Short-term Intake Rate

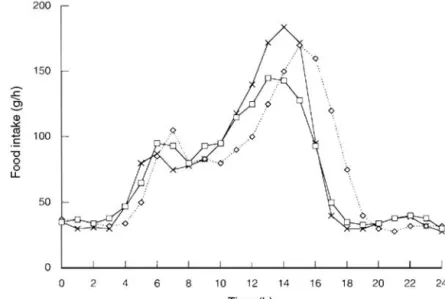

Circadian Rhythms of Feeding

The high incidence of aggressive interactions during the period immediately after returning from milking has implications for animal health and nutrition. It is more likely that those lower in the dominance order are prevented from meeting their needs during the day and thus are forced to meet their demands by eating in the middle of the night.

Food Restriction and Fasting

It is likely that the size of the first meal after a long fast is limited by the capacity of the crop, which acts as a storage organ, the distension of which inhibits feeding. When a larger portion of the limited meal is increased by including straw, there is no reduction in operant responding, indicating that the mere presence of a large amount in the digestive tract does not satiate.

Abnormal Feeding-related Behaviour

The former spent less time eating than the latter when fed ad libitum and more time for unusual foraging. These ad libitum-fed animals grew very rapidly, indicating that high performance is not necessarily an indicator of well-being.

Conclusions

This long storage period makes the physical capacity of the stomachs a potential limiting factor for intake and greatly affects the rates of digestion, breakdown and further passage of food particles. Grinding a forage also increases its rate of flow out of the rumen and allows increased voluntary intake.

The Mouth

Changing the digestibility and rate of passage of forage results in parallel changes in intake (Van Soest, 1994). Although grinding reduces the digestibility of food because the food stays in the rumen for a shorter time, the total weight of nutrients absorbed daily increases.

Oropharyngeal Receptors

For example, supplementing low-protein forages with urea increases digestion and transit rates and allows for greater intake. De-afferentation of the buccal region in the pigeon, by the section of the trigeminal nerves, leads to loss of interest in food, although drinking and grooming are not affected; clearly, in this species the taste and texture of food in the mouth is an important reinforcer of feeding.

Gastric Receptors

Digestibility is the product of the retention time in the rumen and the degradation properties of the food in question. There is irrefutable evidence of mechanoreceptors in the wall of the rumen with afferent fibers to the CNS.

The Omasum

Acids affect the epithelial receptors according to their titratable acidity and molecular size (but not pH) to induce ruminal stasis. It has been reported that ruminal fluid samples taken from sheep immediately after the contractions of the reticulo-rumen were inhibited by intra-ruminal infusion of VFAs were able to elicit responses in the ruminal epithelial receptors of another anesthetized sheep (Crichlow , 1988) ).

The Abomasum

This suggests that total VFA content and relative proportions of VFAs may be important factors in inducing abomasal hypomotility that precedes abomasal displacement in dairy cattle. The mechanisms of the effect of fats and oils on the abomasum are still unclear (Ingvartsen and Andersen, 2000), but may involve gastrointestinal hormones and fatty acid oxidation (see Chapter 4).

Intestinal Receptors

Houpt (1983) suggested that good control of food intake in the pig may be exercised through a combination of three factors that largely act in the duodenum: (i) osmotic sensitivity, which is precise but not directly related to nutritional value; (ii) CCK (cholecystokinin) responses to duodenal protein and fat; and (iii) glucoreceptors in the gut. There are voltage receptors with vagal afferent fibers in the sheep duodenum that also respond to chemicals (Cottrell and Iggo, 1984).

Integration of Multiple Signals from the Gastrointestinal Tract

Given the evidence for important roles of intestinal mechano- and chemoreceptors in the control of food intake in other animal species, it is likely that such receptors are also important in ruminants. Thus, no single stimulus/receptor combination is likely to explain the effects of the physical and chemical properties of the gastrointestinal tract on food motility and intake.

Glucose

The role of the liver in controlling food intake is discussed in more detail below. Thus, in addition to osmotic effects, only hepatic infusion of glucose appears to be specifically involved in the control of intake in chickens.

Liver Receptors

All this evidence points to the oxidation step of hepatic metabolism being key to the effects of the liver on food intake (Forbes, 1988a). Attempts in our laboratory to study vagal discharges from chemoreceptors in the liver of sheep have revealed no consistent responses to propionate injected into the hepatic portal vein (M.H. Anil and J.M. Forbes, unpublished observations).

Lipids

In light of the above discussion, there is clearly much scope for research into the involvement of lipids in the mechanisms controlling uptake in the chicken. Perhaps fatty acids saturate only in the presence of high plasma insulin concentrations.

Volatile Fatty Acids

However, a well-fed animal has high plasma insulin levels, while an underfed one has a low rate of insulin secretion. The high insulin levels combined with high plasma glucose indicated that insulin resistance had developed.

Amino Acids

Once they reached the static phase of obesity, the intake per unit body weight was equivalent to that for maintenance by lean sheep. Vandermeerschen-Doize et al. (1982) found that plasma insulin concentration increased steadily from 10 to 300 U/ml during a 35 week period of ad libitum feeding of sheep; by the end of this period body weight had stabilized.

Metabolic Hormones

There appears to be a seasonal influence on the effects of leptin in sheep, as ICV injection in autumn reduces food intake by 30%, when it is already low (see Chapter 17), while the same injection in spring has no effect (see Chapter 17). Adam and Mercer, 2004). He concluded that neither the brain nor the liver was involved in the reduction of food intake in response to CCK.

Other Hormones

This chapter cannot claim to do justice to the complex subject of the roles of metabolites and hormones in the control of voluntary food intake. The involvement of the brain in the control of feed intake with particular respect to poultry has been reviewed by Denbow (1985), while Forbes and Blundell (1989) have covered the subject for pigs and Baile and McLaughlin (1987) for ruminants.

Lesioning Studies

Lesions in the VMH of young pigs (5-6 weeks old) did not immediately cause hyperphagia, although other metabolic effects were observed (Baldwin, 1985). Electrolytic lesions in the LHA of goats and sheep caused hypophagia, but not aphagia or death.

Electrical Stimulation

Small VMH lesions in sheep did not alter food intake, but this may not have involved destruction of a large enough portion of the critical area, because Baile et al. 1969), who made larger lesions that destroyed the entire ventromedial part of the hypothalamus of goats, did observe overeating and excessive fatness. Stimulation of the lateral hypothalamus causes satiated sheep and goats to start eating again and continue eating as long as the stimulus is applied.

Brain Activity during Feeding

After birth, however, there is very little response to food odors, but a large response to lamb odor, whether it is from the ewe's own lamb or from a foreign lamb. Cells that respond to food sometimes fire in the absence of food; is when the sheep thinks of that food, i.e.

Chemical Stimulation

In the pig, noradrenaline injected into the hypothalamus stimulates feeding while isoproterenol (a synthetic -adrenergic agonist) causes transient anorexia, blocked by propranolol (a synthetic -adrenergic antagonist). It appears that dynorphin and related endogenous opioids may be involved in the regulation of food intake in pigs.

Steroid Hormones

Ionic Changes

ICV injections of sodium or potassium into goats inhibited feeding, whereas slow infusion of similar amounts over 30 min actually elicited feeding (Olsson, 1969). Given that CSF is produced at about 0.5 mL/min, a slow infusion would result in a much lower concentration than would be achieved by a single injection of the same volume, and perhaps very low concentrations of these ions are stimulatory.

Thermostatic Control

Local cooling of the preoptic area and anterior hypothalamus stimulated feeding in satiated goats (Andersson and Larsson, 1961). Although these observations support the thermostatic theory as far as the goat is concerned, warming or cooling the hypothalamus of the pig had no effect on voluntary intake (Carlisle and Ingram, 1973).

CNS Sensitivity to Metabolites and Hormones

Glucose-sensitive neurons in the lateral hypothalamus decrease their firing rate in the presence of glucose locally. Therefore, it is still unknown whether insulin transferred from plasma to CSF is involved in the normal control of food intake.

The Special Senses: Identification of Foods

Nowhere is this more evident than in the area of food choice, discussed in Chapter 7. Many of animals' responses to food are learned (see Chapter 6), and the plasticity of the young animal's brain means that it is possible that different neurons using different transmitter substances are used for the same purpose in different individuals.

Motivation

The liver is the first organ to have a fairly complete picture of the results of eating a particular food in terms of the supply of metabolites. Specific nutritional deficits or general restriction of nutrients will increase hunger and the animal's motivation to consume food (Lawrence et al., 1993).

Learning

This is evolutionarily advantageous, even if the nutritional value of the feed has not changed, as the animal mainly recognizes the feed by taste and smell. When the animal learns that it is safe by taking small amounts of the feed, the normal intake rate can be resumed.

Learned Aversions

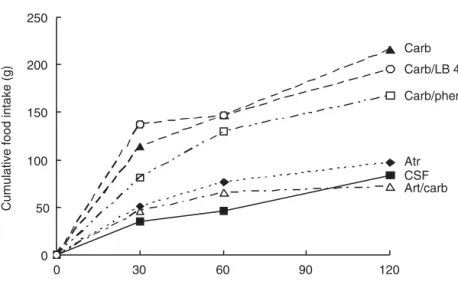

6.2, became progressively averse to food colors associated with CCK - clearly the effects of the hormone are unpleasant and the birds have become conditioned to believe their discomfort is caused by food of a certain color - the identity of the color is irrelevant. The next day, a preference test was performed in which 500 g of flavored and 500 g of unflavored concentrate were placed at different ends of the food trough and the time each animal switched from one food to the other was recorded.

Conditioned Preferences

In the only relevant study in ruminants, non-lactating cows were given a rumen balloon inflated with 12 liters of water for 2 hours, after which they each received 500 g of unflavored or citrus-flavoured concentrates (Klaiss and Forbes, 1999). The reason for inflating the balloon before the concentrate meal was to avoid the disruption associated with the inflation that coincides with the critical time just after US exposure - eating flavored or unflavored foods.

Continuum from Preference to Aversion

The difference between the thresholds in the two experiments is probably related to the different basal diets between the experiments. Thus, a food that the animal is conditioned to believe alleviates a deficiency becomes preferred over other foods, while one that is thought to be in excess of the same nutrient becomes aversive.

Trade-offs and Interactions

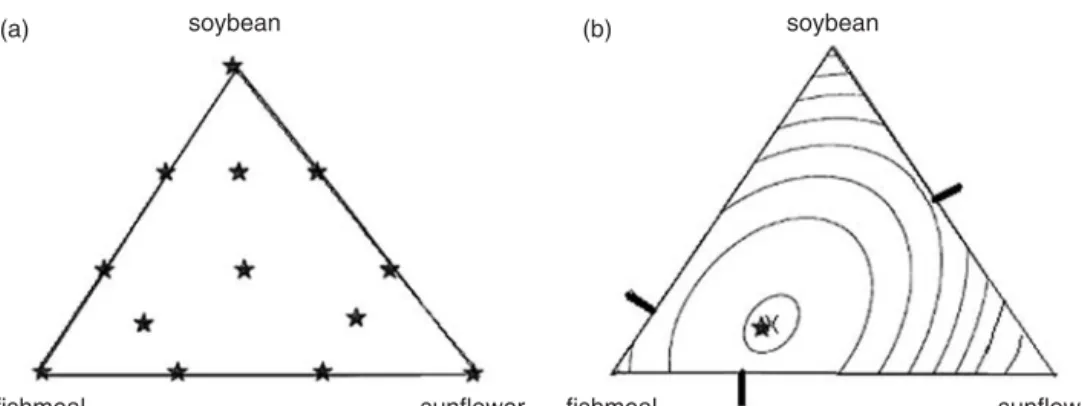

However, when another set of animals received all three test foods and all three associated ULs simultaneously during the learning phase of the experiment, the animals took a mixed diet (see Fig. 6.4b), reducing their chances of learning the associations. To study this type of trade-off, Ginane et al. 2002) offered heifers poor hay ad libitum and a limited amount of better quality hay on the other side of the test arena.

Relearning Following a Change of Food, Animal or Environment

These changes occur slowly and the animals have sufficient time to learn whether small increases or decreases in intake are necessary to maintain minimal discomfort. Thus there is a whole new balance of factors needed to achieve optimal metabolic comfort, which takes the animal a long time to get to the right place, hence the slow increase in early lactation (see Chapter 16).

Timescale of Aversions and Preferences

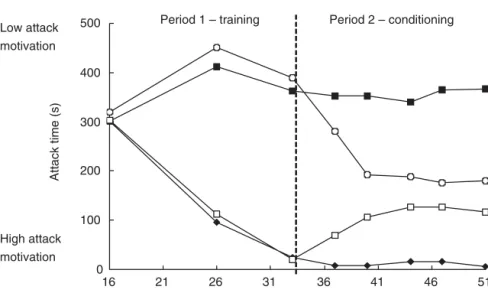

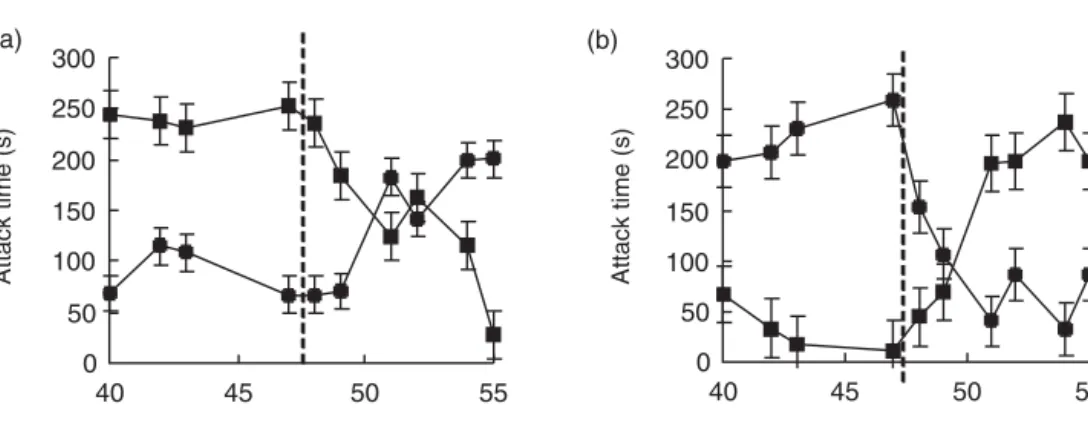

It is to be expected that the speed of learning will depend on the extent to which the animal has been moved from its normal state, e.g. 6.6, the area to the left of the vertical dotted lines shows that they 'attacked' the high protein food significantly faster than the low protein food, whether the high or low protein food was colored green.

Social Components

When offered wheat at a much later time, those given it when they were 3 weeks or older ate more than those with no prior exposure or those exposed in the first 2 weeks of life. There is also fear of unfamiliar troughs, with a reduction in the time taken to eat wheat if it was fed in troughs from which the sheep had previously obtained hay.

Position of Food Cues

In a further demonstration of the power of observing adult eating, pre-weaning exposure to molasses-bridge blocks was found to have a greater impact on later intake than post-weaning exposure. It is not useful to intentionally confuse animals by switching the position of the two foods each day in food choice experiments, a point that seems to have been missed by some researchers.

Palatability’

Two foods with very different sensory and chemical properties were offered to sheep without any differences in the composition of the digestive tract. The realization that it is necessary for animals to be able to distinguish between foods with different nutrient compositions according to color, taste and/or position, and that they must be able to learn to associate the sensory properties of food with the metabolic consequences of eating. them, made it possible to envisage a learned appetite for each of the essential nutrients.

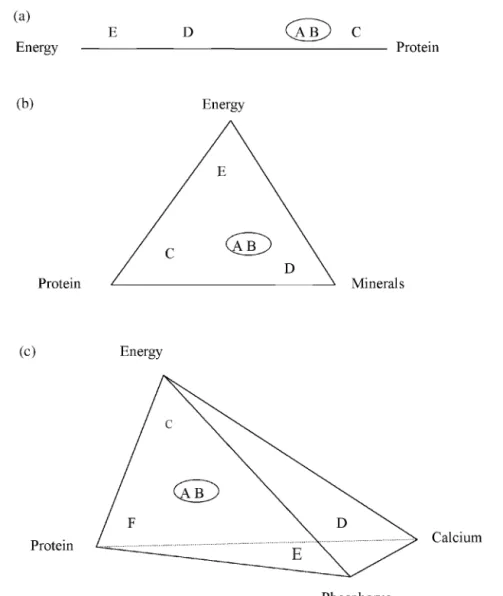

Theory of Diet Selection

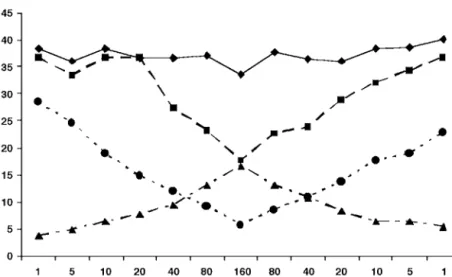

A–F are foods in positions representing the content of the two, three or four nutrients. A second important point is the variation in total intake between animals (the position of the 25th day's intake on the horizontal axis varies from 12 to 20 kg).

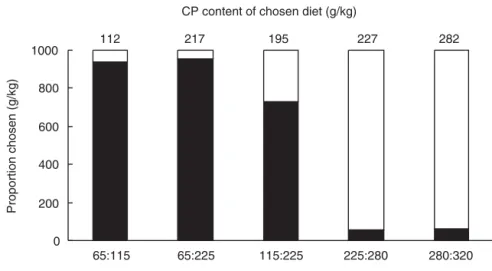

Evidence for Diet Selection: Protein as an Example

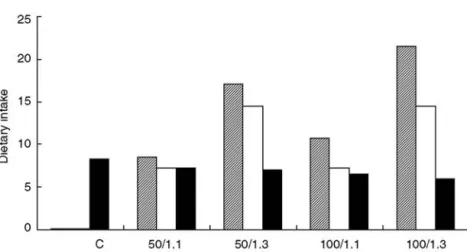

The CP content of the two foods offered is shown at the bottom of each column and the resulting CP content of the chosen diet at the top (from Forbes and Shariatmadari, 1996). The CP content of the two foods presented is shown at the bottom of each column and the resulting CP content of the chosen diet at the top (from Kyriazakiset al., 1990).

Prerequisites for Diet Selection

It only takes a few hours for chickens to recognize a change in the protein content of the feed. Over a 2-week period, there was no effect of the trained pig on growth rate.

Mechanisms of Diet Selection

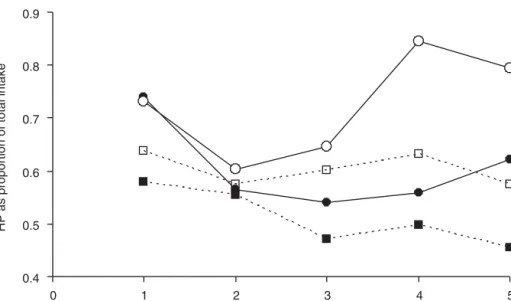

After cessation of force-feeding, birds that had been force-fed the two highest levels of protein continued to have higher voluntary food consumption, but at a lower percentage of HP, and deposited less protein in the body lifeless, than birds with strength. fed with low-protein foods. In ruminants, the products of digestion in the rumen can be expected to influence diet selection.

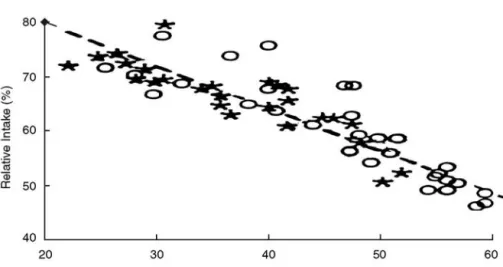

Physiological State

As with broilers, growing pigs show a decrease in the protein:energy ratio of the diet they choose from high- and low-protein foods (Kyriazaki et al., 1990). This decrease was entirely accounted for by a reduction in the amount of low-protein food (120 g CP/kg) selected (the other food contained 240 g CP/kg), so that energy intake was reduced, but total protein intake was not affected. (Roberts and Azain, 1997).

Self-medication

The stability of ruminal fermentation is an important condition for the efficient functioning of the microflora. It is clear that they were choosing the dose of analgesic that relieved the pain or discomfort of the limp.

Practical Uses of Diet Selection

Successive batches of food are made with increasing proportions of whole grains to give a steady increase in the proportion of whole grains calculated to meet the requirements of the average bird. When whole grain and balancer are fed to broilers at alternating 8-hour periods, there is good choice: the higher the protein content of the balancer, the greater the proportion of wheat eaten.

Matching Food Composition with Requirements

Relationship between amount of food organic matter (OM) offered and amount eaten according to the model of Oosting and Nordheim (1999). In many cases these are developments of simpler hypotheses briefly described in Chapter 1, which postulated that nutrition is controlled by a single factor, usually acting in a negative feedback fashion.

Energostasis

Limitation of Intake by Bulk

With uncut forage, intake is likely to be limited by the capacity of the alimentary canal and the dynamics of breakdown and passage of food particles (see Chapter 3). Predictions of feed intake were highly correlated with observed values (r = 0.78) and, unsurprisingly, were found to be particularly sensitive to changes in the model for the allowable mean DM content of the rumen, the content of digestible cell walls in the feed and the rate of passage of particles out of the rumen.

Constraints Models and the Two-phase Hypothesis

The history of studies of voluntary feed intake in farm ruminants shows that initially (until the 1960s) all emphasis was on a positive relationship between food digestibility and how much animals would eat, rather than the negative relationship that was mainly is seen in simple-bellied animals. This assumption is made in the model of Illius and Gordon (1991) and possible metabolic factors are not taken into account.