Although presented as utopian, the smart city actually represents a drastic and myopic reconceptualization of cities for technological problems. This logic makes the smart city appear value-neutral and universally beneficial – as if it were the only reasonable way forward. For technologists, the benefits of increased efficiency are so obvious that the smart city transcends social and political debate—indeed, renders it obsolete.

This siren song of finding objective, technical solutions to social problems is dangerous, especially when we are dealing with technologies as powerful as those in the smart city. The smart city is therefore based on a false dichotomy and blinds us to the broader possibilities of technology and social change. To the extent that the smart city revolutionizes urban life, in other words, it will.

In this respect, my challenge to the smart city is fundamentally pro-technological: I strongly believe in the ability of technology to improve municipal governance and urban life.

Footnotes

The Livable City

The Limits and Dangers of New

Ben Green

In fact, the utopian society with ubiquitous self-driving cars is incoherent and undesirable. If parking lots are developed outside city centers, self-driving cars will need to drive to and from those facilities. If self-driving cars regularly drive in and out of the urban core without occupancy, the number of vehicles on the road could increase dramatically.

As cities are designed to facilitate self-driving cars and, in turn, alternative forms of transportation. They analyzed the pros and cons of the potential ownership models for self-driving cars: private ownership (like cars are owned today) and shared on-demand use (like Uber). Henry Claypool, Amitai Bin-Nun, and Jeffrey Gerlach, “Self-Driving Cars: The Impact on People With Disabilities,” Ruderman White Paper (January 2017), p.

Daisuke Wakabayashi, “Uber's Self-Driving Cars Struggled Before Arizona Crash,” New York Times, March 23, 2018,.

The Smart Enough City • The Smart Enough City

The Democratic City: The Social

Determinants of

Technology’s Impacts

The Just City

Machine Learning’s Social and Political

The Responsible City: Avoiding

Technology’s

Undemocratic Social Contracts

The Innovative City

The Relationship

The Smart Enough City: Lessons from the

At this point, we have discredited many promises of the smart city and demonstrated the perverse effects of tech glasses. New mathematical techniques helped scientists track the environment and calculate, from the size and age of each tree, the amount of wood it would produce.2 However, the natural complexity of forests got in the way: irregularly distributed trees were difficult to measure. and the abundance of other wildlife drained resources that might otherwise help trees grow bigger and faster. Scott attributes the growing appeal of this perspective in the twentieth century to the development of the helicopter and airplane.

In his 1935 paean, Aircraft, he described aerial perspective as “a new function added to our senses.” And when Le Corbusier surveyed from above 'the cities where it is our destiny to be', he was nervous: 'The plane labels the city as old, dilapidated, frightening and sick.'11 So Le Corbusier saw no choice but to do this. doing. strive for a new start. Unlike the previous capital Rio de Janeiro, where streets and public squares functioned as 'points of conviviality' full of festivals, children playing and adults mingling, Brasília was 'a city without crowds'. the design of the city merely provided anonymity. Although underfunding and political neglect were also to blame, the Brasilia-esque design of these complexes (such as the Fort Greene Houses in Brooklyn) has helped make them what the journalist Harrison Salisbury called "the new ghettos" and "human cesspools" .20 Furthermore, these supposedly benevolent projects often provided cover for the mass relocation of lower-income and black residents,21 leading James Baldwin to declare that “urban renewal .

Jane Jacobs, who diagnosed these schemes as "the plundering of cities", criticized top-down, superficially rational planning in 1961 in The Death and Life of Great American Cities. But because the technological spectacles of the day were forged in the fires of those methods, high modernists like Le Corbusier and Moses could not see what was beyond the. To put the problem in the terms of Jane Jacobs, those looking through technological glasses are once again diagnosing "the kind of problem that is a city." Rather than grappling with cities as problems of organized complexity or with the fundamental social and political challenges of urban life, smart city idealists describe cities as abstract technicalities.

The stated desire to create "the best possible city" reveals Y Combinator's myopic belief that an objectively optimal city exists, overlooking the politics, history and culture of cities, as well as the diverse and often conflicting needs and wants of urban residents (indeed, it's hard to imagine Y Combinator, a company full of Silicon Valley wealth, sharing a definition of "best" with the many communities displaced by that wealth). The digital order presented in this utopian vision of the smart city echoes the visual order of. But after several public meetings at which the company revealed scarce details about its plans, one local technologist declared that "the public engagement process is off the rails."38 Moreover, the project's fast timeline makes it almost impossible for the public to have a significant influence on its development.

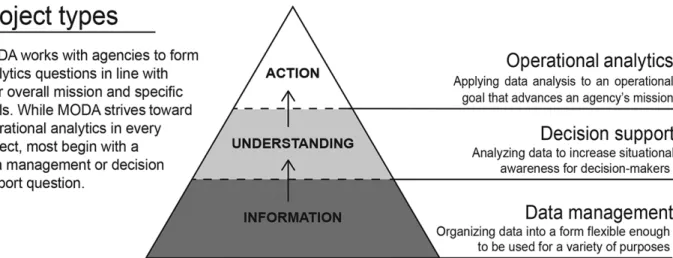

So far, - the playbook begins, - the many 'Smart City' pilot projects we've undertaken here in Boston have ended with great presentation and collective uplift. No one really knows what to do next, or how technology and data might lead to new or improved services.” The Playbook then lists six candid recommendations, starting with.

Address complex problems rather than solve artificially simple ones

We all bear the responsibility to push these efforts towards the ideals of smart enough rather than smart cities. To support and advance these efforts, I have summarized five essential principles of Smart Enough Cities that have emerged throughout the book. In contrast, Smart Enough Cities more fully understands the complexity of urban problems and therefore better recognizes the limits and possibilities of technology.

This allowed Columbus to move beyond some of its simplistic initial notions and develop effective mobility reforms that address the real problems residents face. As Carla Bailo explains, “We really needed to look at it from a more holistic perspective.”54 Columbus cannot remove barriers to mobility or equity with a single technology or policy reform, but its efforts will alleviate some of the everyday challenges that residents face .

Implement technology to address social needs and advance policy,

Prioritize innovative policy and program reforms above innovative

Smart Enough Cities create their most significant impacts through policy and process reforms that carefully address local needs. In fact, many of the success stories we examined involve relatively simple data analytics and technologies deployed to support innovative policies. Their implementation was successful because improving technology is only one form of innovation—a good program that relies on simple technology is better than a bad program that uses advanced technology.

Eager to be seen as innovative and racially neutral, police departments have enthusiastically embraced predictive policing software. But they miss the point: Communities need a fundamental transformation of policing practices and priorities, not an algorithmic enhancement of the same old behavior. By providing the appearance of neutrality, predictive policing algorithms actually justify and increase discriminatory inequalities and policing practices, making systemic reforms even more elusive.

Instead, Smart Enough Cities must follow what I call the "limited technology test". When considering the use of a new technology, city leaders should ask the following. For example, Johnson County sought to reduce incarceration and improve social services, and began providing assistance to individuals suffering from mental illness to improve their lives and keep them out of the criminal justice system. Johnson County generated these benefits not by discovering a new, foolproof algorithm to optimize and legitimize existing police practices, but by reforming its programs to address community needs and then.

Ensure that technology’s design and implementation promote democratic

Develop capacities and processes for using data within municipal

Municipal leaders like Amen Ra Mashariki in New York City and Joy Bonaguro in San Francisco demonstrate how to implement data to improve local governance—not by expecting data to magically optimize government or solve local problems, but by building relationships with departments and promote best practices for maintaining and sharing data and training city staff on how to use data to improve their operations. Smart Enough Cities should follow their lead and reject smart city rhetoric that prescribes newer and more advanced technology as the way for city governments to quickly solve any problem. The realization of these solutions looms as a crisis in urbanism: the smart city will be a place where self-driving cars suffocate city centers and weaken public transport, where democracy is reduced to sending pictures of potholes with an app, where the police use algorithms to to justify and perpetuate racist practices where governments and corporations monitor public space to control behavior.

But no matter how often we are told that the age of the smart city is inevitable and inevitable, a better future is possible. We can create livable cities, where simple mobility technologies mitigate inequality and improve public health. We can create democratic cities, where communication technologies help new participatory processes that empower the public.

We can create responsible cities where new technologies are designed to support privacy and democracy. We can create these smart enough cities if we only have the wisdom to seek them out. Scott, Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed (New Haven: Yale University Press.

Le Corbusier, Den strålende by, 202; Senseable City Lab, "DriveWAVE by MIT SENSEable City Lab," http://senseable.mit.edu/wave/. Bianca Wylie, "Debrief on Sidewalk Toronto Public Meeting #2—Time to Start For Forside, Extend the Process," Medium (6. maj 2018). Jascha Franklin-Hodge, i Knight Foundation, "NetGain Internet of Things Conference" (2017), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=29u1C4Z6PR4.

Mayor's Office for New Urban Mechanics, “Boston Smart City Playbook” (2016), https://monum.github.io/playbook/. Mimi Kirk, “Why Singapore Will Get Self-Driving Cars First,” CityLab (Aug. 3, 2016), https://www.citylab.com/transportation/2016/08/why-singapore-leads-in-self-driving-cars /494222/; Annabelle Liang and Dee-Ann Durbin, “World's First Self-Driving Taxis Unveiled in Singapore,” Bloomberg, August 25, 2016.