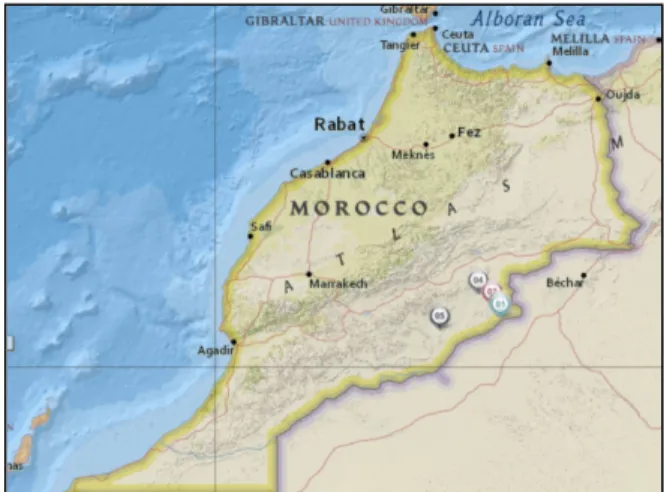

Although my research focuses on farmers in the Moroccan desert, my path began in New Mexico. I first visited Morocco in 2016 and felt at home in the country's southern desert, which lies on the northern edge of the Sahara. In the wake of the Reconquista and the Inquisition, the first Spanish expedition entered New Mexico in the 1530s.

13 Bruce Maddy-Weitzmann, The Berber Identity Movement and the Challenge to North African States (Austin: University of Texas Press. The division between the Maghreb in the western part of the Arab world and the Mashrek in the east has a political dimension that in the present The Maghreb is economic activity and political authority centered on urban areas in the Mediterranean climate of the northern coast.

Literature Review

Geertz's "The Wet and the Dry" compares the environmental politics of two small irrigation systems, one in Bali and the other in Morocco. Also called foggāra, khettāra, falaj and kārez, qanāt systems are found in various parts of the world and are especially widespread in the Middle East and North Africa. 42 Saskia Van der Kooij, Margreet Zwarteveen and Marcel Kuper "The Material of the Social: The Mutual Shaping of Institutions by Irrigation Technology and Society in Seguia Khrichfa, Morocco," International Journal of the Commons 9, no.

Juan Arellano, a New Mexican poet and writer, describes the cultural origins and role of the acequia in New Mexican society, including mention of the acequia's ties to Morocco. This research takes Rivera's work a step further by directly examining the institutions of Moroccan sāqiya communities, in part through the lens of the acequia. He also writes that in the tragedy of the commons, the prisoner's dilemma, and the logic of collective action models, "individuals are perceived as trapped in a static situation, unable to change the rules that affect their incentives." Instead of relying on models and 54 metaphors, Ostrom turns to empirical evidence—real communities of individuals who have built cooperative institutions to successfully and sustainably manage shared resources.

However, many of Ostrom's case studies come from other irrigation systems, including Valencia's Huerta system and the Philippines' Zanjera system. Although Hamid comes to a different conclusion than Sen, he also only analyzes governance at the highest levels of the state. Muslim societies are not temperamentally suited to the complexities of democratic politics.” 60 Joffé builds on the work of anthropologists Ernest Gellner and David Hart, both of whom studied informal, indigenous political institutions that developed independently of the government within Moroccan tribal structures.

According to Joffé, Gellner and Hart argued that “the concepts underlying [indigenous political practices] actually constitute a traditional political culture, which in turn should find an echo in much more recent political experience today. My research shows that the ruling institutions of sāqiya and khettāra demonstrate the existence of a democratic political culture in southeastern Morocco.

Methodology

My research uses Ostrom and Joffé to extend Sen's argument, showing that there is institutional diversity in the Islamic world that includes democratic values at the local level. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy defines democracy as a "method of group decision-making characterized by some kind of equality among the participants in an essential stage of the collective decision-making." The concept of "group decision-making" overlaps with 65 Joffé's principles of consultation and consensus. Following the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, I also paid attention to the levels of equality in participation between members of the irrigation community.

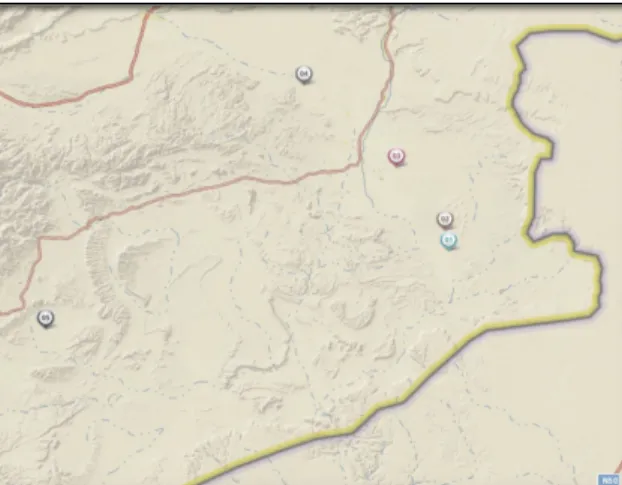

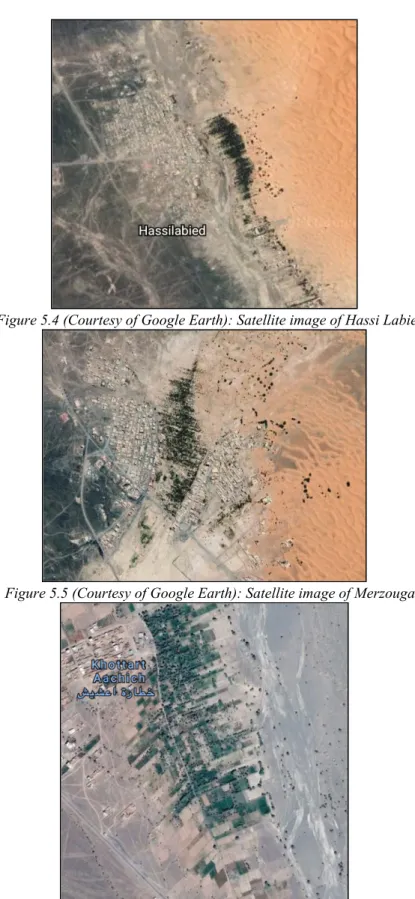

I recruited the interviewees with the help of my friend Youssef Aoujil and his uncle Said al-Fallah, who is a farmer in the Tamazant irrigation community of Merzouga. Youssef and Said helped me gain trust among the interviewees because of their social and cultural standing in the area. I noticed that interviewees who did not know Youssef and Said asked more questions about my research and motivations than those who did.

In some cases, interviewees referred me to other people, especially shūkh as-sāqiya, who they thought would be interested in my research. I came across interviewees who used the Tamazight words inghorān and hāssi instead of the Arabic khettāra and bīr (well). To overcome language barriers, I sometimes used Youssef and Said as intermediaries between Modern Standard Arabic, local dialects, and Tamazight.

My reliance on Youssef and Said limited my results as I relied on their personal connections for the majority of my interviews, which were mainly concentrated in and around the town of Merzouga. I did not spend enough time in Merzouga to cultivate relationships beyond that of the Aoujil family.

Results and Analysis

In qsar societies like Haroun, not only does the sāqiya society completely overlap with the qsar society, but the sāqiya and qsar governance structures coexist in a common institutional framework. Therefore, only people who pay dues and own land can use the sāqiya's water. In Merzouga, one person holds the deed to all the plots in the Tamazant community.

The physical structures of the sāqiya and khettara are considered common property, as are their waters. For farmers living on the fringes of the Sahara, sāqiya is a regular source of water to irrigate their families' plots. In the lower left corner of the image, an earth barrier blocks the water from flooding a plot of land.

Representation is usually based on the physical division of the sāqiya community into strips running parallel to the sāqiya. The shaykh has the authority to call meetings of the sāqiya community or their representatives. Members of the Tamazant sāqiya community contributed to a legal defense fund that the shaykh used during the arbitration process.

The Shyūkh need their irrigation community to provide the financial support and labor that maintain the physical structures of the saqiya and khettāra. A major sandstorm dislodged large amounts of sand and 101 resulted in the physical collapse of part of the khettāra, cutting off the flow of water to the saqiya. Lhassan Ou L'arbi, sheikh of the neighboring Tahafi irrigation community in Merzouga, expressed his concern that saqiya would die out with the current generation of farmers.

State intervention in the Ziz River, which intermittently provides water to some of the communities I visited and forms the core of the Tafilalet oasis, initially destabilized small-scale, indigenous irrigation using sāqiya and khettāra.

Conclusions

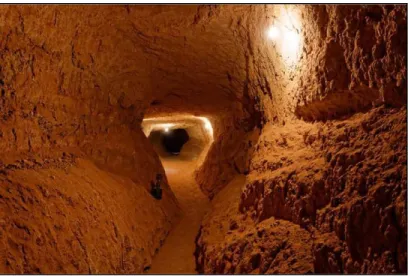

Despite the institutional functionality, the water from the concrete channels flowing from the Hassan ad-Dākhil reservoir evaporates at a faster rate than the water passing through Khettāra's underground tunnels. Building on Elinor Ostrom's findings on commons governance, institutions similar to those of the saqiya and khettāra may govern water or other common pool resources in the Middle East and North Africa. Although Morocco is located on the edge of the Arab world, many of its circumstances, whether environmental, cultural, political or economic, are no different from those found in other parts of the region.

Sāqiya and the khettāra government do not carry the egalitarian ethos of liberal democracies in the US or Europe. My research shows that the most serious threat to the sustainability of khettara and sāqiya is social and economic change that could trigger the collapse of irrigation. Considerable institutional distance separates sāqiya and khettāra from the Kingdom of Morocco; where is the disconnect between local institutions and national ones.

On the other hand, further studies could also explore the potential for democratization of khettāra and saqiya. By examining how sāqiya and khettāra communities expand the franchise to amplify more voices, scholars can gain insights into the conditions that encourage grassroots democratic expansion. By examining 117 other irrigation communities in other parts of Morocco, the researchers could determine the correlation between environmental, institutional, or cultural factors and the level of democracy in an irrigation community.

I am a son of the sāqiya,” he told me, “it is just like my mother; it raised me; it taught me.” I remembered the 118 acequia stories my own mother told me. Before emerging from the ground, the Tamazant sāqiya flows through a concrete tunnel, painted in blue and white, with the text 'water is life' in Arabic, Tamazight, French.

Bibliography Primary Sources

34; Traditional Village Councils, Modern Associations and the Emergence of Hybrid Political Orders in Rural Morocco." The Sais Plain in Morocco." Global Trends in Land Reform: Gender Impacts, edited by Caroline Archambault and EB Zoomers. 34; Applying a Social-Ecological System Framework to the Study of the Taos Valley Irrigation System." Human Ecology 42, no.

Dadda 'atta and his forty grandchildren: The socio-political organization of the ait 'atta in southern Morocco. Boulder, Colorado, USA; Cambridge, England;: Middle East. 34; The collapse of Ksar: Changing patterns of settlement and environmental management in southern Morocco." Africa Today 48, No. 34; Supporting the Transition from State Water to Communal Water: Lessons from a Social Learning Approach to Community Design Irrigation Projects in Morocco." Ecology and Society 14, no.

34;Granaries and Irrigation: Archaeological and Ethnological Investigations in the Iberian Peninsula and Morocco." Antiquity 79, no. 34; Gender, Pastoralism, and Intensification: Changing Environmental Resource Use in Morocco." Yale Forestry & Environmental Studies Bulletin. 34; Twentieth-century climate change over Africa: Seasonal hydroclimate trends and Saharan desert expansion." Journal of Climate 31, no.

The Mutual Formation of Institutions with Irrigation Technology and Society in Seguia Khrichfa, Morocco.” International Journal of the Commons 9, no.

Appendix