SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION

BureauofAmerican Ethnology Bulletin164

Anthropological Papers, No. 53

AN ARCHEOLOGICAL RECONNAISSANCE IN

SOUTHEASTERN MEXICO

By MATTHEW

W.STIRLING

213

CONTENTS

PAGE

Introduction 217

The

TonaM

region 219El Plan 220

Rfo delasPlayas 220

Ceiba Grande 221

PuebloViejo 224

San Miguel 225

Comalcalco andvicinity 226

Comalcalco Ruins 228

Parafso 229

Bellote 231

Isla 231

Tupilco 232

Tapijulapa 233

Atasta 234

Literature cited 235

Explanationofplates 237

ILLUSTRATIONS

PLATES

FOLLOWING PAGB

46. a, The village of Tapijulapa, Tabasco. 6, The Rfo de las Playas,

Veracruz 240

47. Stone headsfromthevicinity ofSanJose delCarmen 240 48. a, Housefoundation, PuebloViejo. b, BallCourt, CeibaGrande 240 49. a, Partofthe Ball Court, Ceiba Grande, b, Pavedfloor. Ball Court,

CeibaGrande 240

50. Portionofstone head,San Miguel, Tabasco 240 51. o. Theruins ofComalcalco. 6, MasonryatComalcalco 240 62. a, Stuccofigures, tomb, Comalcalco. b, Potsherd encrusted masonry,

Comalcalco 240

53. a,

Monument

from La Venta. Villahermosa. b,Monument

fromLaVenta. Comalcalco 240

54. ArtifactsfromthevicinityofVillahermosaandFrontera, Tabasco 240 55. Stuccoconstructionintheshell

mound

atCeiba, Tabasco 24056. Potteryfrom shell moundat Ceiba 240

57. Figurinesandpottery fromshell

mound

at Ceiba 24058. Potteryfromshell

mound

at Ceiba 24059. Potteryfromshell

mound

at Ceiba 24060. Potteryfigurefromshell

mound

at Ceiba 24061. Cylindricalandflatstampsfrom shell

mound

at Ceiba 240 62. Stoneartifactsfromshellmound

at Ceiba 240 63. a, Shellmound

at Bellote. &, Salt-waterchannel near Bellote. _ 240215

216 BUREAU OF AMERICAN ETHNOLOGY

[Bull.164FOLLOWING PAGE

64. a, Making lime from oyster shell, Isla. b, One of the Bellote shell

mounds 240

65. Associatedartifacts ofpottery, shell,andjadefromatombat Isla

—

240 66. Associated potteryvesselsfromatombat Isla 240 67. Potteryfigures of

Maya

typefromTupilco 24068. Adornos fromlarge urns. Tupilco 240

69. a, Stone celt from Rio Candelario. b, Hematite figure from Tapiju-

lapa 240

70. a, Engravedceltfromvicinity of Simojoval, Chiapas, b, Stonestatue

fromAtasta, Campeche 240

71. a, Pottery jaguar head from San Miguel, b, Alabaster vessel from cave near Simojoval, Chiapas, c. Portionofpotteryfigurefrom LaVenta. d, Grindingstonefromshellmound, Ceiba 240 72. a. Prowling jaguarinstucco from Atasta. b, Stuccofragmentsfrom

Atasta 240

73. Basaltmonuments fromLaVentanowatSan Vicente, Tabasco 240

TEXT FIGURE

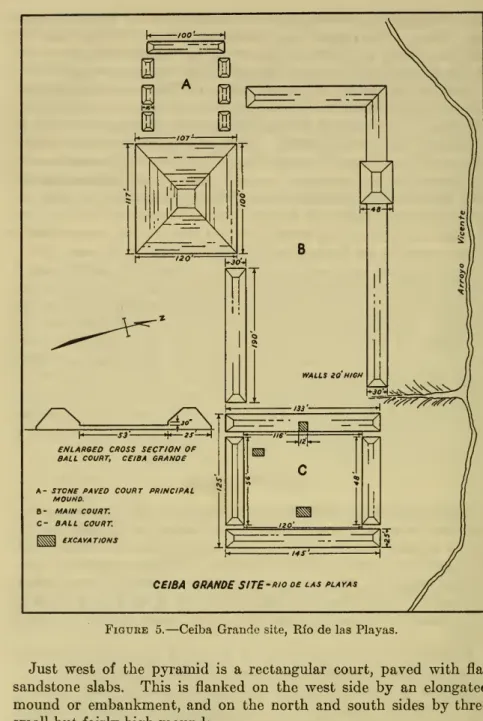

page5. CeibaGrandesite, RfodelasPlayas 222

MAP

15.

Map

ofTehuantepec andadjacent territory 218AN ARCHEOLOGICAL RECONNAISSANCE IN

SOUTHEASTERN MEXICO

By Matthew W.

StirlingINTRODUCTION

One

of the important but little-known archeological areas ofMiddle America

is that portion of southernMexico

lyingbetween

the classicOlmec

territoryand

that formerlyoccupiedby

the ancientMaya.

In 1944 a reconnaissancewas

conducted in this region as part of the National Geographic Society-Smithsonian Institution archeological program, the primary purpose ofwhich was

to estab- lish the easternboundary

of the earlyOlmec

culture.The work was made

possibleby

fundssuppliedby

theNational Geographic Society.The

territory covered during themonths

ofMarch and

April, extendedfrom

theTonala

River eastward to theLaguna Terminos and

the Candelario River. This includes a small part of southern Veracruzand

northern Chiapas,most

of Tabasco,and

the western corner ofCampeche.

Iwas

assistedon

the tripby

RichardH.

Stewart, assistant chief of the National Geographic Photographic Laboratory,

and by my

wifeMarion

Stirling.(Map

15.)In general in this region there are very few roads; rivers

and

trailssupply the principal avenues of travel. Chartered small planes were utilized for several of the longer jumps, but for the

most

part travelwas by

launches, canoes, horseback, oron

foot.The

coast facing theBay

ofCampeche

is low.A

line of sand dunes fringes the water's edgeand

behind these dunesmangrove swamps

extendmany

miles inlandwhere

the water ismade

brackishby

the tides.Back

of thesandy

coast is a chain of large, shallow salt-water lagoons.Along most

oftheTabasco

coast, themangroves

giveway

to fresh-waterswamps

in thelow

flat interior. Thislow

land extends almost to the Chiapas borderwhere

themountains

leading to the central plateau begin.The major

portion of this territory is coveredby

a dense tropical rain forest, interspersedby

lakes,

swamps, and

large rivers,which

are joinedby

anetwork

of connecting sloughs.The

principal rivers are the Grijalva,and

the217

218 BUREAU OF AMERICAN ETHNOLOGY

[Bull.164Map

15.— Map

ofTehuantepec andadjacentterritory.San Pedro y San

Pablowhich

constitutes the lower course of the Usumacintla. In spite ofwhat might seem

an unfavorable environ- ment, the area is fairly well populated.The

1940 census gives 12 inhabitants to the square kilometer, a figurewhich

seems too high.The abundance

of archeologicalremainswould

suggest that thepopu- lation in aboriginal timeswas

greater than atpresent.A number

ofMaya

sites are to be found in this region, themost

important beingJonuta on

the lowerUsumacintla and

Comalcalcoon

theRio

Seco.The

latter is of particular interest since it represents thewesternmost-known Maya

site.Many

of the prehistoric remains, however, are not yet identifiable asMaya,

a factwhich

pointsup

the importance of doingwork

in thiskey

area. Here, theoretically, shouldbe found the chronologicalNo.^SsT^

ARCHEOLOGY, SOUTHEASTERN MEXICO

STIRLING219

link

between

the established culture columns of theMaya

region,on

the one hand,and

of the Veracruz coast,on

the other. In addition, there appear to be relationships with the highlands of Chiapas.There

is evidence also of Toltec influence, an item of considerable current interest. All in all,Tabasco and

the adjacent territory constitute a critical region of primary archeological importance.At

Comalcalco there are anumber

of interesting anomalies.The

architecturein

many

respects istypical ofthe ClassicMaya. Rooms

are

narrow

with extremely thick wallssurmounted

with steep cor- beled vaults.Tombs

contain figuresmodeled

in stucco reminiscent of Palenque,The

structures, however, aremade

of fired bricks instead of stone,and

the substructures are earthmounds

similar to those of Veracruz rather than stone-facedpyramids

with rubble cores.At

Jonuta also there are earthmounds

instead of pyramids, but typicalMaya

stone sculpture exists, withMaya

glyphs.At

Tupilco, near the coast of Tabasco,we

found a site without architecture but with typicalMaya

figuresmodeled

in clay. Thissite lies

some

30 miles west of Comalcalcoand

is the westernmostMaya

outpostyetknown.

THE TONALA REGION

The

Tonald River, theboundary between

the States of Veracruzand

Tabasco, is formedby

the junction oftwo

streams, the Pedregaland

the Rio de las Playas,which

originate in the roughmountains

around the CerroMono

Pelado. After flowing their separateways

through themountains

they join soon after entering the coastal plain.At

the present time the regionwhich

they drain is entirely uninhabited exceptfor the lower reaches.While

working at the site ofLa Venta

in 1943,we

heard stories of ruinsknown

as Pueblo Viejo, locatedon

the Rio de las Playas.On many maps

ofMexico

this site appears in large type as though itwas an

existing city.Unable

to findanyone who had

been there,we became

intriguedand

resolved tomake

a tripup

the river inan

effort to locate it.

Our

unsuccessful attempt todo

so at that time hasbeendescribed elsewhere (Stirling, 1943;Weber,

1945).However, on

this 1943 tripwe

obtained information that convinced us of the existence of the ruins of Pueblo Viejo,which we presumed was

a colonial site.We

were told also of a large pre-Columbian site in thevicinityknown

onlyto oneman,

Vicente Aguilar, a native pioneer livingon

the Rio de las Playas,who was

unavailable to us as guideon

ourfirst expedition.On March

11, 1944, Stewart, Mrs. Stirling,and

I leftLa Venta

in a canoe withan outboard motor, in ordertosurvey theupperreaches of the river.Having

heard of amound

group near the oilcamp

of220 BUREAU OF AMERICAN ETHNOLOGY

[Bull. 164Cuichapa,

we made

ourfirststop atLas Choapas and

tooktheautovia car to theoilcamp.

Here

oneoftheengineers,Roberto Montez,

ledusto thesite,which

IS about 3 miles west of Cuichapa.

The

group is quite impressive, consistingofaverylargelongmound

approximately 500feetlongand

40 feet high. Just east of it is a steep conicalmound

about 50 feet high.South

of this are several smallround mounds. We found no

sherdson

the surface.Although

themounds had

been cleared 2 years before our visit, theyhad

againbecome

covered with a dense second-growthjungle.Leaving Las Choapas we

continuedup

the river.At

El Plan thefirsthigh

banks

appear alongtheriver,and

themangrove swamps

are leftbehind.EL PLAN

At El

Plan, formerlyknown

as Huacapal, there aretwo mounds

about 50 yardsfrom

the edge of the 50-foot-high riverbank.The

largest of these is about 14 feet high

and

isdome

shaped. In front of it, in the direction of the river, is alow

irregularmound

about 5 feethigh.Some

digginghad

beendone on

the east edgeofthelargermound, but

ithad

not beenmuch damaged. The

spacelyingbetween themounds and

the riverwas

evidentlyan

occupation site, sinceabundant

sherds are revealedwhere

digging has beendone

for con- structionpurposes.These

sherds are forthemost

part ofplain buffware

with black interspace as the result of incomplete firing.They

are undecorated except for simple grooves or incising near the rims.

The

principal shapes notedwere

shallow, fiat-bottomed bowls with widely everted rims.A

few obsidian flakesand

flint chips were scattered around.No

figurine fragmentswere seen.

RfO DE LAS PLAYAS

Beyond

the mangroves, the country continued low, with hereand

therelow

hillsand

elevations. Occasional milpas along the riverwere

planted primarily with cornbut

withsome

beansand

bananas.When we

entered theRio

deLas

Playas theriverbanksbecame much

higher. AscendingthePlayasfor 1

hour we came

toalow

hillon

theleft, with a sandstone exposure at theriver's edge. Just

back

of thison

a higher elevation could be seen a group ofmounds and

leveled terraces silhouetted against the sky.An

hour's journeybeyond

this pointwe saw

anothermound

groupon

a highpointback

ofthe riveron

theright.At

Cerro Pil6n the river emergesfrom

the mountains, the rapids begin,and

it isno

longer possible to use a motor.Here

the riverNo.^SsT^^ ^^'

ARCHEOLOGY, SOUTHEASTERN MEXICO —STIRLING 221

passesthrougha

Hmestone

gorgeand

theremainderof thetripis slowand

difficult.The

regionbeing uninhabited, thereisno

land trailup

the river. Justbeyond

the gorge, at the lasthouseon

the river,we

picked

up

our guide, Vicente Aguilar.Near

the house a good-sized stream, theArroyo

deLas

Amates, entersthePlayason

theleft bank.Vicente told us that

on

a hunting triphe had

seen a ruin fartherup

thisstream.

To

reach it one goes2 leaguesup

the Amates,where

it is joinedby

theArroyo

Burro.Then

one follows theBurro

to the west until theArroyo Esperanza

enters it.Near

the headwaters of the Esperanza is a good-sized site with stone-faced platforms, larger than Pueblo Viejo but smaller than Ceiba Grande, thetwo

siteswe examined on

theRio

delas Playas.From Las Amates

it is about 3 days' travel to theArroyo

Pueblo Viejo,on which

are located the ruins of the site of thesame name.

On

the thirdday we

stopped justbelow

a mountain, locally called the Cerro Tierra Colorado, in order tohunt

game.At

this place the leftbank

oftheriverishighand

thelandquitelevelfora considerable distance.Here

along a smallarroyowe saw

aseriesofsmallmounds,

the highest ofwhich was

about 10 feet.Some

were circular inform and

others were of an elongated oval shape.Most had

sandstone slabs scatteredon

the surface.We saw

one natural outcrop of thistype ofstone inthe vicinity

which

gaveussome doubt

as to the arti- ficial nature of themounds. However

their appearanceand

location leadme

tobelieve that they aremanmade.

Itwould have

cost us aday

of travel to testthem, sowe

didnot excavate.CEIBA GRANDE

About noon

of the thu'dday

of our tripfrom

the limestone gorge,we came

to a small arroyowhich

entersfrom

the leftbank

of the Playas opposite a highbank

of blue shale topped with reddish soil.We

gave it thename

ofArroyo

Vicente.The

large prehistoric site,Vicenteassuredus,

was

locatedon

thisstream. After a4-hoursearch, he found it. It is situated on the rightbank

of the arroyo on fairly levelground and was

covered with a very highgrowth

of virgin jungle.A

giant ceiba treewas

growingon

the exact center of thesummit

of the principal pyramid, so

we named

the site "Ceiba Grande."Because of the

heavy

jungle cloak, the real natureand

extent of the sitewas

not apparent to us at first, but after 5 days of clearingand

mapping,we

found that it consisted of aprincipal pyramid,two

adjacent courts,and

aball court (fig. 5).The pyramid

is approximately 50 feethighand

is faced with sand- stone slabs.A

badly ruined wide stairway leads to thesummit on

the north side.222 BUREAU OF AMERICAN ETHNOLOGY

[Bull. 164A- STONE PAVeO COURT PRINCIPAL MOUND.

B- MAIN COURT.

C- BALL COURT.

KSS$Si EXCAVATIONS

CEIBA ORANDESITE-Riooelas playas

Figure 5.

—

CeibaGrandesite, Rfo delas Playas.Just west of the

pyramid

is a rectangular court,paved

with flatsandstone slabs. This is flanked

on

the west sideby an

elongatedmound

orembankment, and on

the northand

south sidesby

three small but fairly highmounds.

North

of thepyramid

is a large court about 400 feet longand

100 feet wide. This is flankedon

the northand

west sidesby

an L- shapedembankment. The

long or north area of theL

is enlarged, at the point opposite the pyramid, into a fair-sizedmound. The

NrssT^'^^^"

ARCHEOLOGY, SOUTHEASTERN MEXICO —STIRLING 223

southside ofthe big courtisflankedin part

by

thenorthwallofcourt"A,"

the principal pyramid,and by an embankment which

extends eastwardfrom

the northeast corner of thepyramid

for a distance of 190 feet. Thisembankment

runs level fora distanceof 140 feetand

then slopesdownward

toward the ball court,which

lies at a lowerlevel.

The

east wall of the big court isformed by

the west wall of theball court.The

ball court itself, although it appears symmetrical to the eye, actually is not.The

insidemeasurements

of the northand

south ends are, respectively, 48 feetand

56 feet, while the inside measure-ments

of the eastand

west sides are 120 feetand

116 feet. Part of thisapparentirregularitymay

bedue

tothefactthat the innerpaving has been buried in the taluswashed down from

the surroundingembankments.

The

structures at the northand

south ends of the ball court aresomewhat

shorter than the width of the floor, leaving anarrow

passage at each corner.The

entire surface ofthe walls is faced withflatslabs ofsandstone,

and

thebaseofeachwall hasavertical sectionwhich

extends 2}^ feetabove

the floor.From

this point the walls slopeupward

at an angle of45° to the top ofthewall,which

isabout 20 feet high.The

floor has been fully leveledand

consists of a well- fitted paving of sandstone slabs laidon

a base of clean yellow sand.This sand is not a natural formation, but

was

apparently carried in (pi. 49, 6).The

only excavationswe made

were in the ball court.We dug two

small pits into the floorand

ran a trench 12 feet wide into the central section of the west wallfrom

the floorlevel, in order to gain amore

accurate picture ofthe construction ofthe court. Thistrench yielded a fair sampling of sherds.There

wereno

figurines, butwe

encountered a few prismatic obsidian flakes.The

great majority of the sherds were of a coarse brickRed Ware,

undecoratedand

sand tempered.A

few sherds of this type were black,which may have

been an accident offiring.There

were also a few thin sherds offineuntempered

paste.There

were no sherdson

the surface nor couldwe

findany

in thebed

of the arroyo adjacent to the site.Inthedenseforestsouthofthe

pyramid we saw some more mounds,

but did nothave

time to survey them.An

interesting feature of CeibaGrande

is the fact thatmost

ifnot all of the

mounds and embankments

are faced with stone slabs.This feature, along with the

paved

courtsand

ball court, clearly indicates that this site is something quite differentfrom

themound

groups of the adjacent coastal-plain region of southern Veracruz

and

Tabasco. Rather, itwould seem

to bean

outpost of a culture originatingin theChiapashighlands.The

ballcourtswhich we

foimd224 BUREAU OF AMERICAN ETHNOLOGY

[Bull. 164in Chiapas in the region of the

La Venta

Riverwere ofthe expanded-end

typefor themost

part, but nevertheless I feel that theremay

besome

relationship.PUEBLO VIEJO

A

short distanceabove

theArroyo

Vicente, theArroyo

Pueblo Viejo enters the riverfrom

the left bank. Directly in front of the arroyomouth,

there is a large bar.A

short distanceabove

this is a secondlarge bar. Justback

ofthis, thesiteofPuebloViejo islocatedon

highlevelground on

the rightbank

of theriver.The

site is near theriverand

liesbetween

itand

a small arroyowhich

entersthePlayas just below.The

site is about 400 yards square,and

consists of ap- proximately 30 rectangular platforms withmasonry

wallsmade

of flat slabs ofsandstonelaidwithout cement.They

arebetween

2and

3 feet high, depending

on

the size of the platform.The

largestwe measured was

66by

30 feetand

the smallest 25by

10.We

selected one forexcavationwhich was

30by

18 feet,withwalls2 feet 10 inches high.At

a distance of 7 feet 7 inchesfrom

the northwest corner therewas

a stone staircase 17 inches wide consisting of 3 steps, each with a rise of 7 inches.The

long axis of the platformwas

oriented almost exactly northand

south. This appeared to be the case with the other platforms as well.The

spacebetween

the stone wallswas

filled with earth, level with the top.

We dug

a trench 5 feet wide extendingfrom

the middle of the north wall to the middle of the south walland

an intersecting trench connecting the centers of the eastand

westwalls. (PI. 48, a.)A

considerableamount

of plain buff potsherdsand

a quantityof flint chipsand

rejects were recovered.The

onlyEuropean

object foundwas

alarge square hand-forged iron spike. Thislayat a depth of 1 footnear the middle of the platform.At

the north edge of the site aretwo

deep excavations or holes.On

the rim of one of these are the remains of part of a stone wall.They might have

been wells, but it isdifficult to seewhy

wellswould have

beennecessarywith the riverso close athand.My

firstimpres-sion

was

that this sitewas

of colonial originand had

been occupiedby

mestizos or Europeans. This thoughtwas

induced primarilyby

thefact that

we

expectedit to be acolonial sitesinceitwas

placedon

the oldmaps.

Thisseemed

tobe confirmedby

the findingofthe iron spike,thestonesteps,and

the rather exact orientationofthestructures.On

the other hand, the potterywas

all of native type (a fact not necessarily conclusive),and

themasonry was

very similar to that of structureswe

later foundin the vicinity ofOcozocoautla in Chiapas.My

present behef is that Pueblo Viejo is a late-type aboriginal site.nS.^'^sT''"

^'''''

ARCHEOLOGY, SOUTHEASTERN MEXICO —STIRLING 225

SAN MIGUEL

Leaving

Coatzacoalcosby

small plane,we went

to Cardenas by-way

ofComalcalcoand

Villabermosa.From Cardenas we

biredmulesand

a guideand

rode tbe 42 miles toSan Miguel

in 12 bours.Tbe

first part of tbe trail is tbrougb comparatively open country

and

remains so until after crossing tbeArroyo Limon, wbere

itenters tbe forest.At Limon

tbereis asizablegroup ofsmallmounds, and

about 5 miles beyond, near tbe trail, is anotber similar group.At

botb of tbese sites, sberds arevisibleon

tbesurface. Justbeyond Limon

the trail passes over a pair of small parallel longmounds.

San Fernando

is tbe ruin of a former baciendawbicb

stood at tbis place.Tbe

trail crosses tbe ruins of a brick structure.At

onepointit passes

between two

standingbrick columns.A

few yardsback

of tbese, bidden in tbe tbick brusb,was an

aboriginal stone figurewbicb we

laterlearnedbad

been brougbtfrom

tbe site atSan Miguel by

aman named

Villar,many

years agowben

tbe baciendawas

in operation.Tbe

figure is of basalt, representing a seated individual. It is4K

feet bigb.Tbe bead

is tbe bigb elongatedOlmec

type.Tbe

ears are rectanguloid, longand

narrow.Tbe

eyes arealmond

sbapedand

slanting.

Tbe

features are badly erodedand now

almost indis- tinguisbable.Tbe

baseis flat.Tbe

I^neesand arms

are broken.Tbe

present village ofSan Miguel

consists of a few scattered thatcbed butsand

is locatedon

an arcbeological site. It is near tbe beadwatersof tbe Blasillo River, on tbe lower reacbes ofwbicb

is tbe site ofLa

Venta.Tbe

arcbeological site ofSan Miguel

consists of anumber

of good-sizedmounds and

a deeppond

orborrow

pit similar to thoseatCerro delasMesas and San

Lorenzo.Tbe most

interestingmonument wbicb

vv^esaw

attbesitewas

lyingin tbe trailbetween two mounds. One

oftbesemounds many

yearsagobad

been flattenedon

top in order to build a church ofthatch.At

the time ofour visit tbe churchbad

beenabandoned and was

falling to pieces.Tbe

stone consists of thedome-shaped

upper portion of a large basalt bead, brokenoffat thelevelofthe eyes. Initspresent conditionit isaboutSji feet high. Scattered over the

roimded head

are a half dozen ormore round

faces, includingonedirectlyon top.Each

ofthesefacesissurrounded

by

a circlefrom which

radiate five stepped elementsand

a long triangularpoint at thebase.Some

oftbe smaller faceson

tbeback

appear tohave

beenrubbed

orworn

off.The

rear of thebead

is flattened as is the case with the

Olmec

Colossal beads. (PI. 50.)About

300 yards south of tbis stone, well hidden in tbe jungle,was

another fragment ofwhat bad

evidently been a large stonemonument. One

surface of this issmooth

with a deep groove in it.226 BUREAU OF AMERICAN ETHNOLOGY

[Bull. 164Carved on

thissmooth

surface inlow

relief are three "flame"- or leaf-shaped elementssomewhat

like the carvings inlow

reliefback

ofthe

head

ofthe principalfigm-e of altar4 atLa

Venta. Itisimpos- siblenow

to tell the natm-e of themonument from which

this rather massive fragmentwas

broken.We

were informedby

themen

of the village that a few years ago in anearby

field part of a carved basalt figurewas

exposed.Being

curious, they

dug

itup and

foundittobethefigure ofaman somewhat

larger than life size. Their curiosity satisfied, they reburied it.

At

the time of our visit the field

was

covered with aheavy growth

of zacate,but

themen

claimed they could locate the figure later in the seasonwhen

the grasswas

burned.One man had

a small pottery hollowfigurinehead

ofa jaguar withround

ears. Itismade

ofalight buffware which had

oncebeen

covered with a whitesHp. (PI. 71, a.)WhUe

nota particularly large site,San Miguel

isimportant because ofits obviousOlmec

affiliations.Upon

our arrival therewe

learned that the hard 12-hour ride to reach itwas

not necessary.A

launch leavesLas Choapas on

theTonala

River tvidce aweek and

goes toArroyo

Prieto notmore

than 5 milesfrom San

Miguel.From

there one can reachthesiteon

foot orby

horseback. Itis alsomuch

closerby

trailfrom La Venta

than it isfrom

Cardenas.COMALCALCO AND VICINITY

From Cardenas

to Comalcalcowe

traveled in a truck overan unimproved

road.Most

of this section is a rich agricultural district.The

roadwas

linedwithlargecacaoplantationswhich

wereovergrown and

neglected at the timewe

passedby

them.Such

productivelands couldhave

supported a very large aboriginal population.The

present city of Comalcalco is locatedon an

island in theRio

Seco,and

it has a population of approximately 3,000.One

of ourfirst acts

upon

arrivalwas

to visit Prof.Rosendo Taracena

at the Instituto Comalcalco, a school forwhich

hewas

largely responsible.In the school

was

a considerable archeological collection that hehad

assembledfrom

the region. Included in the material weremany

specimens recently obtained

from

the large shellmound

at Ceiba, near Paraiso,from which was

taken the shell used in building thenewly

completed roadfrom

Comalcalco to Paraiso.The

place ofhonor

in the collections is heldby

a basalt seated figurefrom La

Venta. This

was

placed in a corner partly coveredby

awooden

frame designed toresemble the arched nicheson

theLa Venta

altars.This figure

was

one offivewhich

a wealthymahogany

dealerby

thename

ofPolicarpo Valenzuelahad removed from

the site atLa Venta

more

than50 years agoand

brought to hishaciendaSan

Vicente,nearAldama

in Tabasco. InAldama

the greatMexican

RevolutionNo.^^sT^^

ARCHEOLOGY, SOUTHEASTERN MEXICO

STIRLING227

began,

and San

Vicentewas

the first of the haciendas of the big landowners to be destroyed.The

fiveLa Venta monuments

layamong

the ruinsformany

yearsuntiltwo

ofthem

weretransportedto Villahermosawhere

they were placed in the grounds of the school(pi. 53, a). In 1939 Professor

Taracena removed

a third one to his institute in Comalcalco (pi. 53, b). Laterwe made

a trip toSan

Vicente to seeand

photograph thetwo

remainingmonuments. At

the timeofour visit, theroad

from

Comalcalco toAldama had

prettymuch

gone to ruin,and

itwas

with considerable difiiculty thatwe

reachedAldama by

car.Aldama,

the "Lexington" of Mexico, once a prosperoustown now

consists of a few scattered thatch hutsand adobe

housesaround

a largeopen

plaza inwhich

are anumber

ofcement

seats.Here was

fought the first battle of theMexican

Revolutionin 1910.The

roadfrom Aldama

toSan

Vicente proved to be impassable for our car, sowe made most

ofiton

foot.Along

the road, just outside Comalcalco, aretwo

smallmounds where

a brick factorywas

being built.Halfway between

Comalcalcoand Aldama, on

theArroyo

Seco at the site of the oldPemex camp,

is a fair-sizedmound and some

smaller ones.The

trailfrom Aldama

toSan

Vicente passes oversome

smallmounds

about three-fourths of theway from Aldama. There

are sherdson

the surface.The

remainsofthehaciendaare laiownlocallyas the"Casa

Vieja."The

ruins of the once fine structure arenow

buried in jungle.The

broken brick walls wi'apped in strangler figsand

covered with para- sitic plants look as ancient asany Maya

ruin, although itwas

only 1913when

the haciendawas

destroyed completely.Lying

in the rubble of the old patio,we

found thetwo monuments. Under

the circimistances theyseemed

to us to epitomize theimpermanence

ofhuman

achievement. Policarpo tookthem from

the wildernesswhich

the great centerofLa Venta had

become,and

broughtthem

towhat

he considered the luxuriouspermanence

of the great hacienda.Now La Venta

is, as a result of the oil industry, oncemore

at the doorstep of civilizationand

easily accessible, whileSan

Vicente, in utterruin,isburiedina wilderness ascompleteasthatwhich

formerly engulfedLa

Venta.One

of the stones, 45 inches high, represents aman

sitting cross- legged, leaning forward shghtly, thehands

clasping the feet.A

band

across the forehead passes completelyaround

the head.The

facial featm*es are considerably eroded,

and

part of theupper

leftarm

has been battered off; otherwise the sculptureis in prettygood

condition (pi. 73, a).37092&—57 17

228 BUREAU OP AMERICAN ETHNOLOGY

[Bull. 164The

other stone, 36 inches high, is especially interesting. It represents theOlmec anthropomorphic

jaguar in parthuman,

part animal posture.The

figure is seated with the left frontpaw drawn

under the body, the rightpaw

lying alongside thebody

with the realistically carved foot lying pads up.The head

is largeand

represented as looking upward.The

elongated eyeshave

branching"Olmec"

eyebrowsand

themouth

is the typicalOlmec

"tigermouth."

The

forehead issomewhat

concaveand

thehead

flat across the top, with the usual notch in the middle of the forehead.The

tail is stylizedand shown

as branchingon

each side like theeyebrow

conventionalization.A

fresh breakshowed

thatsomeone

very recentlyhad knocked

off the base of the tail.The

piece soremoved must have

been carried away, sincewe

searchedfor itin vain. (PI. 73, b.)A

figure quite similar in appearancewas

found atArroyo

Sonso, 25 kilometers southeast of Coatzacoalcosand

15 kilometersfrom

theTonala

Kiver(Nomland,

1932).These two monuments

are relatively small asLa Venta

sculpture goes.The

bases ofboth

pieces are perfectly flat, that of the jaguar having an opening through itwhich

passes through the lap.COMALCALCO BUINS

The Maya

ruins ofComalcalco lieon

the right side of theKIo

Secoand

less than an hour'swalk from

the town. Considering therelative accessibility of the siteand

its great importance, it issomewhat

difficult to understand

why

it has been so neglectedby

archeologists.Charnay

visited the ruins for 10 days in 1880, publishing several inadequate accounts, but quite properly calling attention to the importance ofthe site (Charnay, 1887). (Pis. 51, a, b; 52, 6.)In 1925 the

Tulane

University expedition under the direction of FransBlom

(1926-27) visitedand mapped

thesite, excavating atomb

containing a procession of figures

modeled

in stucco. (PI. 52, a.)Save

for thesetwo

brief forays, archeologistshave managed

pretty successfully to detouraway from

the locality.The

principalmound

isacompositestructure

more

orlessrectangularinform

withtwo

large apronsprojectingfrom

thewestcorners. Itismore

than 100feethighand

probably measures almost 1,000 feet along the east-west axis.The

remains of the buildings still standing are of large, flat well-fired brickssetinheavy mortar made from burned

oystershell.The

walls aremore

than3 feet thick.Although some

oftherooms

arestillintact, the site has been pretty welldenuded

of all the paintingsand

stucco"adornos"

which

once embellished it.The tomb

excavatedby Blom had become

exposed to the weatherand

the stucco reliefs were deteriorating although still in fair shape.No.^S"^"^"^^^

ARCHEOLOGY, SOUTHEASTERN MEXICO

STIRLING229

All oftheglyphs in the

tomb

were gone. It is possible that similartombs

occm-under the corresponding apronon

thenorthwest portion ofthemound.

Many

years ago themajor

part of the walls of themain

buildingwas

torndown

in order toobtain bricks to buildhouses nearComal-

calco. Despite the wreckage of the structures

which surmounted

thesite, therehasbeenvirtually

no

excavationin themounds

themselves, so in one sense the vandalism has been superficial. Because of its strategic location as the westernmost outpost of the ancientMaya

civilization, Comalcalco offers a splendid opportunity for finding in juxtaposition, materials typical of thesouthern Veracruz cultures

and

those oftheMaya

proper.Although

the buildings are architecturally pureMaya,

the substructuresresemble the large earthmounds

of the southern Veracruz areamuch more

than they dothe stone-facedMaya

pyramids.

While

finestuccomodelingreminiscentofthatatPalenquewas

characteristic of Comalcalco, stone sculpture seems to be absent.PARAISO

The

tripfrom

Comalcalco to Paraiso over thenew

shell-surfaced roadrequiredonly 30 minutesby

car.The

roadisitselfan

attenuated archeological site, beingcomposed

ofa mixtureofshelland

potsherdsfrom

the great shellmound

nearCeibaon

the lowerRio Seco.Paraiso, a

town

with a population of about 1,800, has apparently not changedmuch from

its appearancewhen

visitedby Charnay

in 1880.While

intown we

viewedsome

private collections of materials thatcame from

the shellmound

duringthe road-buildingperiod.The

shellmound was

locatedon

theleftbank

oftheRio

Seco about a mile above Ceibain thedirection ofParaiso.The

locationwhere

themound was

actually situatedisknown

asPalma, butsince Ceibaisthe betterknown

place, Iam

referring to it as the CeibaMound.

When we

visited the site the bulk of themound had

been hauled away, butsince thebasestillremained withnumerous

excavationpits exhibitingvertical faces 8 or 10 feet high,itwas

stillveryinstructive.The body

of themound

goesdown

well below the water tablewhich

is at the surfacelevel oftheriver.

At

the time of ourvisitsome

shellwas

stillbeing takenfrom

themound.

The

baseofthemound was

about 300 yardslongby

100yardswide.Our

informants toldus that the highest partformerly reacheda height of 15 meters.The body

ofthemound

consistedmainlyofoystershellwith occasional pockets of conch shell, sand,

and

stray miscellaneous shells. Floors,bothofburned

clayand

cement, arefairlyabundant

in the remaining lowerportion ofthemound.

In severalinstances cross sectionsshow

3 or 4 floors superimposed (pi. 55, a).The

layers ofcement

are about aninch thickand

were usually the sidesand

topsof230 BUREAU OF AMERICAN ETHNOLOGY

[Bull. 164 rectangular platforms with shell cores.The

corners of the platformswere rounded and

the walls slopedtoward

the top so that each plat-form was

actuallyintheform

ofamuch

truncatedpyramid

(pi. 55, 6).A man who

lived at the site all during the period of excavation said that there were usuallyhuman

burials with offerings beneath these platforms,which

rangedfrom

2 to 4 feet in height. According to his account,which

accorded withwhat

otherinformants told us,most

of the betterspecimenscame from

theupper

levels of themound. The

highest

summit had

immediately under the surface alargecement

or stucco-covered platform, the sides ofwhich

were decorated with"alligators"

modeled

in stucco relief. Thismade

a rather impressive appearance,and

the worlonen, hopeful of treasure, lostno

time tearingitapart onlyto findthat theinteriorconsistedofapureoyster- shell core.Among

the findswhich

our informantremembered was

a string of pure white, highly polished stone beads, little pinch pots filled with red paint,some

legless stone metates,and

a stone "idolo"about2 feet high representing a seated

man.

Here and

therein themound

canstillbeseen depositsofwhite limemade by

burning oyster shell. Potsherds wereabundant

with the base ofthemound

sowell exposedand

freshlyexcavated;half vessels, large rimsherds,and

basal supports lay about in profusion,many

in situ. This materialwas

representative of the early period of themound

structure.Some

of the sherds are of incised ware, occasion- ally with zoned designs set offby

punctate areas. Paintedware

is eithermonochrome,

darkred (specular hematite), orpolychrome

con- sisting of orangeand

blackon

buff.A good many

of the vesselshad

acream

slipon

the exterior, butno

further painting. All the painted designswe saw

were geometric in character.There

were partsofcomales,withouthandles,and

fragmentsoflargeollas.There was

another type of large shallow vessel withround bottom and

a shortincurvingneck

with wide everted rim.Some

of these, judgingfrom

the sherds,must have

been 18 inches in diameter. Figurines appear to be relatively rare, such as there are, being of the hollow variety.The

finerware

consists of shallow tetrapod vessels, usually with fluted melonlike sidesand

flange base. Effigy ormammiform

supports terminatein aflat cylindricalnubbin.

Some

sherds revealed thata shallow annular or ringbasewas

sometimes used.A common

typewas

around-bottomed

jar wnth sloping shoulderand

a high neck, therounded

portionbelow

the shoulder being roughenedby

textile impressions or scalloping applied with the edge ofa pecten shell.There was

apparentlyno

shell tempering.The

nature of the ceramics is bestshown by

the illustrations (pis. 56-61).No^SsT^"

^'^'^'

ARCHEOLOGY, SOUTHEASTERN MEXICO —STIRLING 231

BELLOTE

From

Ceibawe

droveby

cartotheendof theroadwhere we

hired a canoetovisitthe shellmounds on

theLaguna Mecoacan. We

passed miles of coconut groves alonglow mangrove

flats inan

area similar to thatofthe 10,000 island region of Florida (pi. 63, b).We

passed several smallshellmounds

withsections exposedby

the waves. In alittlemore

than 2 hourswe

reached Bellote,where

the bigmound

group is situatedon Andres

Garcia Island.There was

a thatchedhouseatthe footofthemounds owned by

R. Unolfo Cordoba,who

guided usover themounds which

hehad

partly cleared forculti- vation. (Pis. 63, a; 64, b.)The

Bellote group is quite impressive.There

are four principalmounds

placed in close proximityand

several smaller scatteredmounds,

principally toward thenorthand

east.The

sides ofthemounds

aresteepand do

not runtogether aimlessly in the usualmanner

ofshellmidden mounds.

The

centralmound

ismore

than 40 feet highand

ismore

or less flaton

topwhere

parts of acement

floormay

still be seen.At

asomewhat

lower level on the east side is a flat-topped apron. Just south of this is a slightljT" lower, steep symmetrical conicalmound.

East of the central

mound

is a large,somewhat

elongatedmound

about 25 or 30 feet high, while north of thecentral

mound

is anothermound

withtwo

summits, probablylessthan20feet in height.North

of this are three low, elongated

mounds

running parallel with their axis inan

east-west direction.Our

guide told us that in clearing his milpa they foundsome

glass beadsoflargesize.Potsherds were

abundant on

the surface,and on

superficial exami- nationseemed

similar to theware

at Ceiba.Although

ofshell, the Bellotemounds seem

definitely tohave

been constructed,and

arenot simply refuse heaps.When Charnay

visited Bellote around 1880, he said there werestill ruins of a temple on the

summit

of the principalmound, and

pictured a stuccorelief similar in style to those at Palenque.When we

visited the site, the only visible evidence of a structurewas

theremainsof acement

floor.ISLA

On

our return tripfrom

Bellotewe

stopped to photographsome

natives burninglime in a fashion thatmight have

been usedby

the aboriginalinhabitants,who

alsomade

limefrom

oystershells.A

sort of crib ofmangrove wood was

constructed, forming a plat-form which was heaped

high with oyster shells. Thiswas

fired, reducing the shells to lime (pi. 64, a).232 BUREAU OF AMERICAN ETHNOLOGY

[BnLi..164At

a place called Isla, not farfrom

this point,we

stopped tosee aman by

thename

of Francisco Chable.He and

his sonhad

justdug

a smallmound on

hisproperty,and we made

photographs of the interesting material recovered.The mound was

of earthand

about 5 feet high. In thebody

of themound

were three pottery vessels.One was

a round-bodied spouted" teapot," theupperpartpainted darkredand

highlypolished, the lower part incised (pi. 65, a-1).The

spoutis unsupported, the base flatwithavestigial annularringsupport.The

othertwo

vessels were incrusted with "caliche"and

the painted decoration, if any, did not show.The ware

ofboth

of thesewas

brick red in color.One was

a round-bottomed, high-necked jar with the rimexpanded

intobowl

form. Itwas

9 incheshigh (pi.65, a-3).The

otherwas

awide-mouth

jarwith simple incised ornamentation (pi. 65, a-2).Below

the base of themound was

a grave about 4 feet deep, with traces of thebones ofa child.Accompanying

thesewereanumber

of artifacts.There were two

pottery vessels.One was

a spouted effigy pot of incised buff-coloredware

11 inches high, the other a pot of exceptionally fineware

in theform

of a coiled shell, 9by

8 inches.The

latterhad

shortcylindricaltripod supports,and

ashort spout,and

theinteriorwas

painteddarkredand was

highlypolished.The

outsidewas

covered with acream

slip.On

the sidewas

a rectangular car- touche with an elaboratelymodeled

designwhich

probablyrepresents a stylized serpenthead

(pi. 66, a, h).Also with the burial

was

the profile of ahuman

skull carvedfrom

shell, about 3 inches in diameter,

and

a pure white, well-preservedhuman

head, beautifully carvedand

polished,made from

a massive piece ofsome

marine shell. It is IK inchesin height.With

it were 7 cylindricalshell beadsand

15 bright green jade beads,and

a pair of very small earspools of thesame

material.The

shellhead was

in position as the central piece of the jadebead

necklace.There was

also astring of 12 polished

and

perforated shells (pi. 65, h, c).TUPILCO

From

Paraisowe

drove to the finca of AlejandriaMarques

Gutier- rez,widow

of GeneralGutierrezwhose

fatherwas

killed in the battle ofAldama.

She had

a veryinteresting collectionmade by

herhusband on what had

formerlybeenhisproperty,nearTupilco.The

material consisted primarilyofelaborate"adornos"inMaya

stylewhich had

been brokenfrom

large cylindricalm-nsorincensarios.The

best pieceis alife-sizehead

wearing a jaguar headdress. Part of therim

of the cylindrical urn towhich

ithad

been attached is still present. (Pis. 67, 68.)Noi^fsT^

ARCHEOLOGY, SOUTHEASTERN MEXICO —STIRLING 233

The

presence of aMaya

site at Tupilco is of considerable interest, since thiswould make

it the westernmostMaya

outpost yetknown.

The

siteconsistedofsmallshellmounds

withno

otherarchitectural features.TAPIJULAPA

The

picturesquetown

of Tapijulapa is situated at the base of the central mountains, at the junction of the Escal6nand

Oxolatdn Rivers in the extreme southwestern part of Tabasco.There was

formerlyan

archeological site here near the river,and

specimens are occasionally foundon

a gravel bar in front of thetown

following floods.One

such specimen (pi. 69, b)was

a fine highly polished figurinemade from

a very hard reddish-brown hematite. Itwas

4 inches in height.The

nativewho

found itwould

not part with itbecause he said he

was

using it as a "santo" in hishouse.We

alsosaw

afinepolished spindle whorlofblue stoneand

anumber

of quite small polished celts of blue or green stone, all found on this

same

bar.We

spent several days in Tapijulapavisitinganumber

oflimestone cavesand

shelters in the generalvicinity.Near

the airport, a stream of sulfur water flowsfrom

a limestone cavernon

property formerlyowned by

Garrido,when

governor of Tabasco.Near

this stream is a good-sized, flat-toppedmound on which was

built acement

house thatwas

never completed.We

entered the cave for a considerable distance, but since it is a

"wet"

cave there

was no

sign of aboriginal occupation.Near

this spot are themineral springswhere

"Tapijulapa water" is bottled.While at Tapijulapa

we went by

canoeup

the Oxolat^n River to the Cerro Cuesta Chica,where we

visited four limestone cavesand

anumber

ofrockshelters along thebase ofthe limestone cliffwhere

the cavesoccur. Tvv^o ofthe caves are oflargesizeand

contain beautiful stalagmitic formations,some

of the curtain variety being very impressive.In the caves, at the entrances,

we

foundnumerous

potsherds of a red orbuftware.Some

of thesewereofverygood

quality, red slippedand

polished.The

rock shelters contain deep depositswhich

include quantities of snail shells broughtup from

the arroyo.There

are alsomany

flint chipsand

pieces ofstoneknocked from

riverboulders.Excavations here

would

nodoubt

bemost

instructiveand would

yield considerable material.

In Tapijulapa

we

secured a fine slate ax with anOlmec

design en- gravedon

itand

analabasterbowl.The man from whom we

obtainedthem

said hehad

purchasedthem from an

Indianwho

said he found234 BUREAU OF AMERICAN ETHNOLOGY

[Bull. 164them

in a cave ata place called FincaChapayal

nearSanta Caterina,between Almendro and

Simojoval, in Chiapas. (Pis. 70, a; 71, h.)ATASTA

From Ciudad Carmen we went by

launch across theLaguna

deTerminos and

then through a series of mangrove-lined passages to the village of Atasta,which

is scattered for a considerable distance along the waterfront.About

a mile west of thetown

is a group of smallmounds which

probablymark

thesiteofthe ancient Atasta.About

ayearbeforeour arrival,from

oneofthesemounds was

excavated alife-sizestonefigure of a standingman. A

section consisting of the chestand

shouldersismissing.

The

faceisdone

inan

unusualstyleand

isrepresented as wearing a jaguar headdressand

relativelysmallearspools. (PI. 70, 6.)From

thissame mound, we

were told,were

taken several pottery vesselsand

a clay "tablet" elaborately engraved.These

were takenaway by some

visiting "ingeniero."When we

visitedthesite, thecornerofonemound had

recentlybeendug

into. Thismound

apparentlj'^ covered a stucco-coated platform with amodeled

frieze of prowling jaguars.On

therounded

cornerpiece

which had

beenremoved was

the figure of one of these jaguars about3 feet in length (pi. 72, a).The

underside of the stucco coatingwas

covered with bosses or protuberancesso that the coatingwould

adhere bettertothe claycore.These

were probably producedby

punching holes in the clay before the stuccowas

applied. (PL 72,b.)Thisparticularfindishighly suggestiveof Toltecinfluence,bringing to

mind

the prowling jaguar friezes atTula and Chichen

Itza.The

schoolteacher in Atastahad

a small archeological collection said tohave come

principallyfrom

this site. It contained one small completebowl

ofbrickred ware, fairly thinand

quite hard.Another

piece consisted ofabout three-fourthsof a tetrapod, flange-base bowl, also ofred ware.There

werealso ahalfdozeneffigylegsfrom

similar bowls, the effigies consisting of grotesquehuman

facesand

animal forms.Three

copper bellswere of the elongated oval variety. One, 2 inches in length,was

cast to represent cordwrapping around

the upperportion.The

others, 1 inchin length, wereplain.The

pottery, inform and

design, appeared to resemble thatfrom

Ceiba, but the red-coloredware would seem

to indicate that itwas made from

a different type of clay.We

were not entirely convinced that this materialcame from

thesite described above.A number

ofyears after our reconnaissanceHeinrich Berlinvisited Atastaand

hasreportedon

it briefly (Berlin, 1952-54).NrSl"""'^^^'

ARCHEOLOGY, SOUTHEASTERN MEXICO —STIRLING 235

LITERATURE CITED

Berlin, Heinrich.

1952-54. Archeological reconnaissance in Tabasco. Carnegie Inst. Wash-

ington, Dept. Archaeol. Current Reportsvol. 1, No. 7.

Blom, Frans, andLaFarge, Oliver.

1926-27. Tribes and temples. Tiilane Univ.,

New

Orleans. Middle Amer. Res. Ser., vol. 1.Charnay, Desire.

1887. Theancientcitiesofthe

New

World.New

York.NoMLAND, Gladys.

1932. Proboscis statuefromthe IsthmusofTehuantepec. Amer. Anthrop., vol. 35, No.4.

Stirling, M. W.

1943. LaVenta's greenstonetigers. Nat. Geogr. Mag., vol. 84, No.3.

1947.

On

the trail of La Venta Man. Nat. Geogr. Mag., vol. 91, No. 2.Weber,

Walter

A.1945. Wildlife ofTabasco andVeracruz. Nat. Geogr, Mag., vol. 87, No,2,

Feb.