Fosu is a former president of the National Economic Association (1997) and the African Finance and Economics Association (1998 and 1999), both based in the US. Nduluis in the African region of the World Bank, where he serves as an advisor to the vice president.

Demography

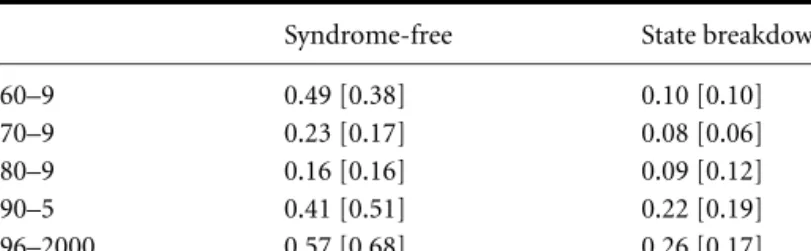

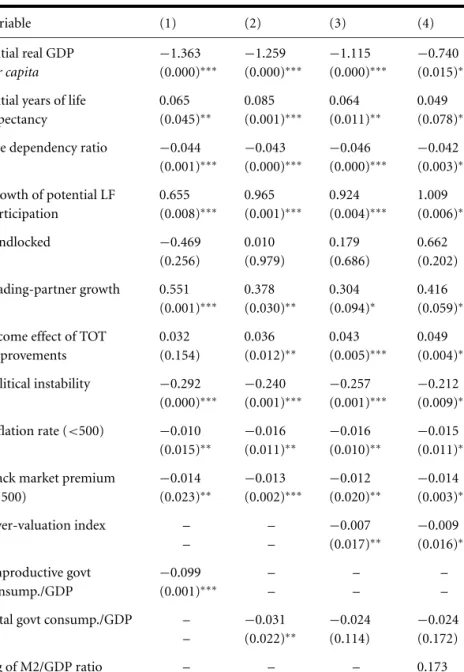

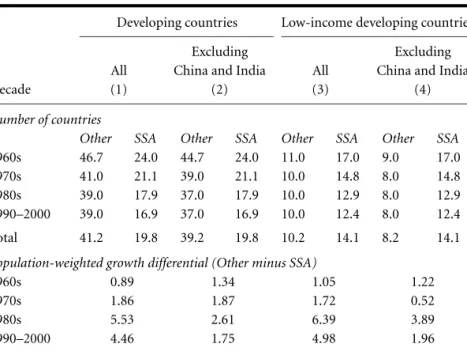

In figure 1.6, Africa's dependency ratio rises steadily, surpassing historical developing country norms by 1970 and remaining above it throughout the rest of the century. Rising dependency ratios have a mechanical impact on growth, diluting the contribution of any given real GDP growth per worker to real GDP growth per capita: table 1.1 indicates that this effect alone accounts for almost 0.4 percent of per capita growth per year over the full 1960–2000 period, comparing SSA with other developing regions.22Bloom and Sachs (1998) highlight additional adverse impacts that operate through the discouraging effect of high dependency ratios on national saving and the quality of human capital formation.

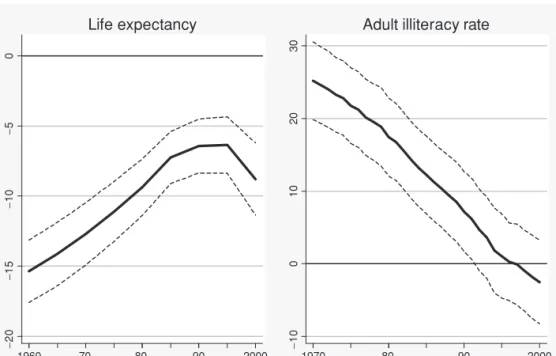

Human development

Life expectancy rates had also steadily converged with income-adjusted global rates for most of the period, but, unlike literacy rates, they show a marked slowdown beginning in the mid-1980s. and a remarkable reversal with the onset of HIV/AIDS in the 1990s. Figure 1.7 simply confirms that measures of human development fared better: they continued to advance at a slow pace, in the face of very limited improvements in overall living standards. 23.

Geography

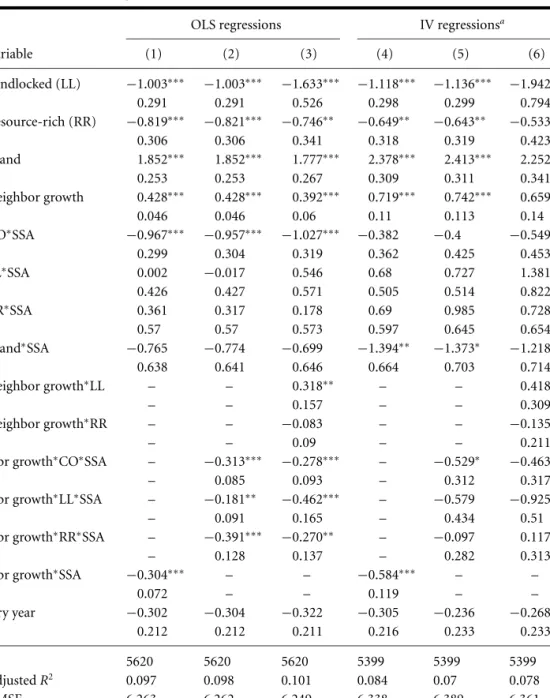

Collier (1997) focuses on governance and argues that natural resource exports dominate because they are unusually robust to institutional failures in the public sector. Other channels for the natural resource curse implicate governance even more directly, characterizing resource rents as a source of institutional failure in the public sector.

Peace

The continent's long detour to authoritarian rule roughly corresponds to the U-shaped evolution of its growth performance. With this background, we turn to the treatment of governance in growth econometrics, focusing on the core functions discussed above.

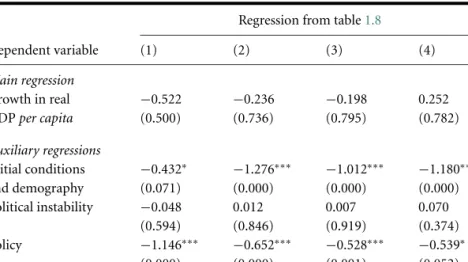

Policy

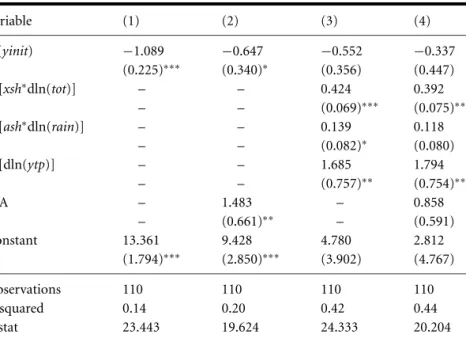

The sum of this coefficient and the coefficient of non-coastal non-coastal as a measure of the net (direct and indirect) impact of non-coastal non-coastal on projected growth is 0.17 and 0.17, respectively, in the three regressions. Panel (2) shows the associated reductions in black market premiums outside the CFA area: the process of exchange rate unification was only briefly interrupted by a period of political instability in the early 1990s.

The institutional environment

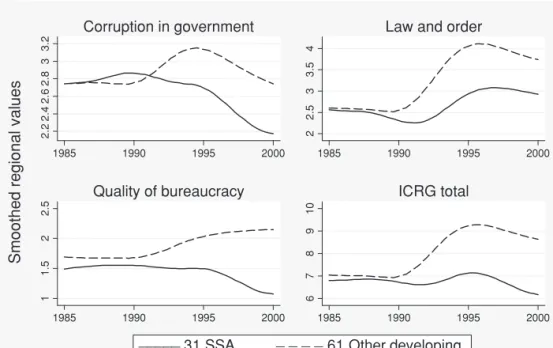

Like the indices of political institutions reviewed earlier, measures of the institutional environment tend to reflect expert judgments about actual practice rather than collections of formal rules. In contrast to measures of policies and political institutions, measures of the institutional environment show little general tendency to improve in SSA during the 1990s.

Infrastructure

This is consistent with the persistence of clientelistic norms in the face of economic and political reforms (van de Walle 2001) and perhaps with the impact of political liberalization on public awareness of embezzlement by public officials. Bates's chapter 10 suggests a more powerful adverse relationship between political liberalization and institutional performance, based on the shortening of the horizons of political leaders.

Polarization

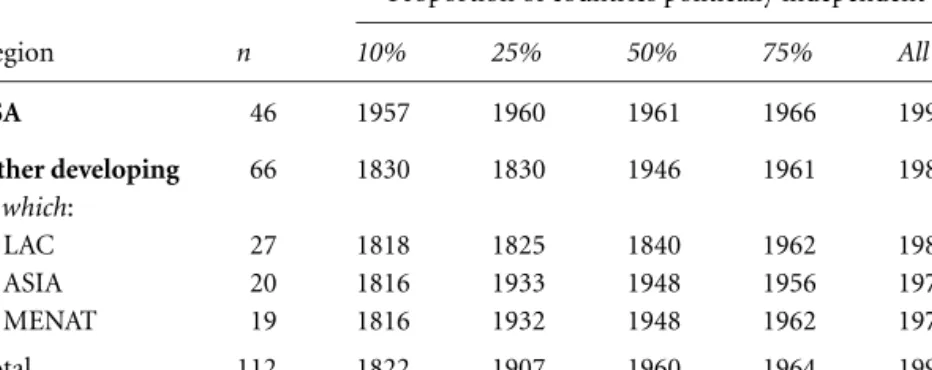

The implications of the syndromes for growth are examined empirically by Collier and O'Connell in Chapter 2. This widening gap was due to both growth acceleration in the rest of the developing world and growth deceleration – to a degree negative – in Africa.

Endowments

In Chad, for example, the absolute value of rents was endogenous because the investments needed for oil exports were delayed due to internal conflicts. Assessment adjustments are needed to return this classification to the first part of the sample because resource rent data have only been available since 1970.

Location

Endowments and location in growth regressions

The most striking difference, however, is in the share of the population living in landlocked economies with scarce resources. The syndromes are not intended to be exhaustive of the ways in which growth can fail.

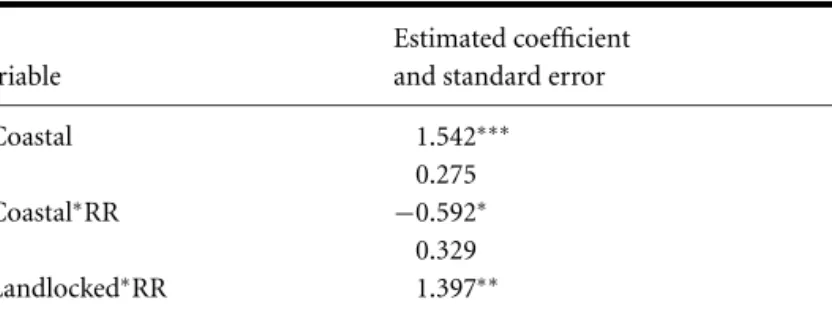

Coastal, resource-scarce economies

During the decade of the 1980s, the coastal, resource-scarce economies of Africa were almost all in the grip of one or another of the syndromes. The persistence of the regulatory syndrome in the resource-scarce coastal economies is indeed significant in reducing the growth of manufacturing exports, service exports and their combination.

Resource-rich economies

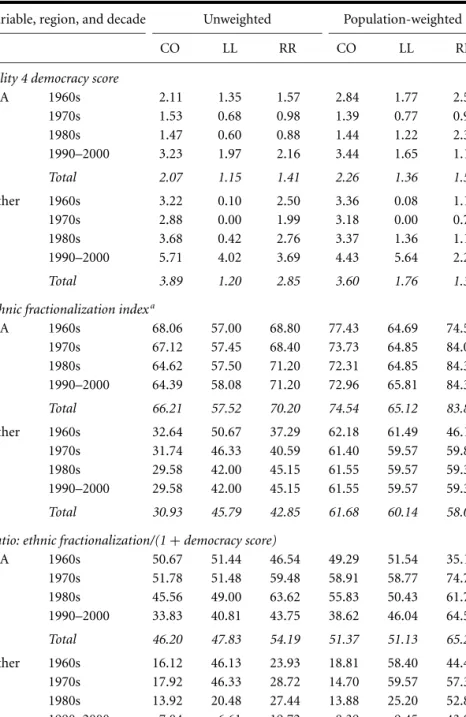

According to this interpretation, resource-rich African countries have fared worse than those in other regions because they are more likely to be characterized by a toxic combination of ethnic diversity and autocracy. From 1970–2000, resource-rich African countries were consistently much more marked by a cocktail of high ethnic diversity and low democracy than other African opportunity groups and resource-rich countries in other regions.

Landlocked, resource-scarce economies

Their more fortunate neighbors usually have their growth opportunities barred by one or other of the syndromes. As part of the Collaborative Research Project conducted by the African Economic Research Consortium (AERC) on "Explaining African Economic Growth Performance" (the "Growth Project"), a number of anti-growth syndromes were identified by the project's editorial committee based on previously commissioned project case studies and other evidence.1 This.

Burkina Faso: 1960–1982 (soft control); 1983–1990 (hard control) Following independence in 1960, Burkina Faso pursued “state intervention-

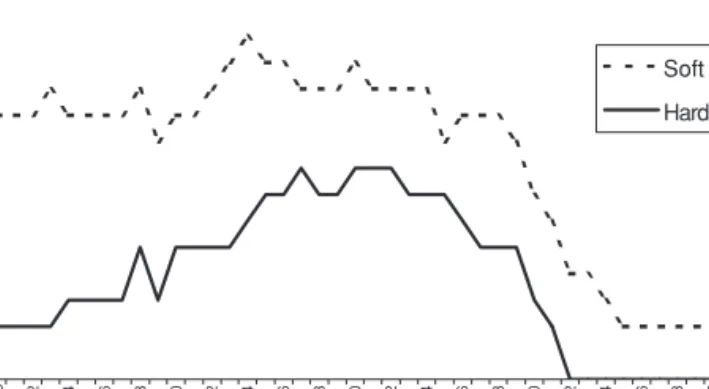

In many cases, marketing boards were established to manage prices, and other state-owned enterprises handled production and distribution. Most African countries engaged in one or both forms of control in their respective histories.

Cameroon: 1960–1977 (soft control)

Chad: 1960–2000 (soft control)

Ghana: 1960–1966, 1972–1983 (hard control)

So, when the military overthrew Nkrumah's government in a coup in February 1966, there were many celebrations in the streets to welcome the change. Apart from the explicitly ideological thrust of the Rawlings regime, which came to power in a coup d'état in December 1981 (following a brief coup by Rawlings in 1979), these governments were not particularly radical, but the governing policies as considered the way out. .

Sierra Leone: 1975–1989 (hard control)

Tanzania: 1970–1985 (hard control); 1986–1994 (soft controls) The genesis of the imposition of strict controls was the strong belief by

Import controls were introduced because foreign exchange reserves were severely depleted due to the government's policy of ensuring universal access to social services. Such resources came from the coffee boom of the 1970s and the constant inflows of foreign aid that went into financing state investment.

Burundi: 1975–1987

Thus, the period 1986-94 could be seen as a transition from hard control to a market-based economy, a transition that required significant political interventions, as discussed below (Mwase and Ndulu2007). However, this state of affairs led to a subsequent period of state collapse, as discussed below (Nkurunziza and Ngaruko 2007).

Sierra Leone: 1969–1990

Togo: 1976–1990

Burundi: 1975–1985

Cameroon: 1982–1993

Nigeria: 1974–1986

However, after the oil crash, the country became one of the most heavily indebted countries in SSA, with total foreign debt peaking in 1990 at over US$33 billion. Much of the debt accumulation arose from the need to maintain certain politically driven spending commitments. an environment of ethnic polarization.

Togo: 1974–1989

With the exception of Obasanjo, all the above leaders came from the North, while oil revenues came from the South, with the implied redistribution of oil revenues to the North. These severe fiscal difficulties led the Nigerian government to seek the assistance of the Bretton Woods institutions and adopt a SAP in July 1986 (Iyoha and Oriakhi2007).

Burundi: 1988–2000

This period of unsustainable spending forced the government to pursue an IMF-led Financial Stabilization Program (FSP) negotiated in 1979 and a series of SAPs that began in 1982. The collapse of the state (often labeled as "state failure" in the political economy literature) is said to occur when conditions are such that law and order breaks down and the government is unable to perform its basic functions.

Chad: 1979–1984, 1985–1993

Public investment then shrunk from nearly 50 percent of GDP in the late 1970s to 20 percent by 1989, while a job freeze reduced the civil service by 13 percent between 1985 and 1988. Hence this acute form of political instability, which could reasonably be judged what is now known as state collapse was not over before the 1993 massacre, after which D'eby deliberately established a regional power-sharing government, with General Kamougue, who had previously led the resistance in the South, as President of the national assembly.

Sierra Leone: 1967–1968, 1991–2000

By default, syndrome-free status tends to identify politically stable regimes with reasonably market-friendly policies. In the immediate post-independence era, syndrome-free status was typically associated with politically conservative governments.

Botswana: 1960–2000

Indeed, the data show that among the forty-six SSA countries, roughly the same number chose syndrome-free policies as those that adopted syndrome policies (see figure 3.1). A syndrome-free regime can also occur, at least briefly, when a military coup replaces an authoritarian government with a disastrous economic history.

Burkina Faso: 1991–2000

The country also received generous donor support based on its status as a democratic state on the doorstep of apartheid South Africa.

Ghana: 1968–1972, 1984–2000

Sierra Leone: 1961–1966

Tanzania: 1961–1967, 1995–2000

Likewise, it was the substantial reduction in aid in the early 1980s, precipitated in part by the global paradigm shift away from the socialist mode of development, that further deepened the budget crisis and forced the government to change direction. Despite the formal adoption of reforms in 1986, political commitment to market-based policies was still lacking, a situation exacerbated by the emergence of competitive multi-party politics.

Togo: 1960–1973

The country had remained a darling of aid donors for years despite (or because of) its socialist mode of development, mitigating the negative impact of accompanying policies and thus postponing Tanzania's need to undertake reforms. Such conditions can be classified into: the international royal paradigm; experience of novice leaders; the degree of group-identity rivalry, defined to include forms of ethnic, linguistic, and religious rivalry; initial institutions; and the role of government in fulfilling society's time preference for development.

Reigning international paradigms

The attraction of the early African leadership to socialism can be explained by several factors. First, a number of the leaders were strong believers in the need for relatively equitable growth, viewing capitalism as a mechanism for a few individuals to get richer at the expense of the masses.

Experience of the initial leaders

Similarly, the rural origins of leadership in Botswana guided rural-friendly measures, avoiding urban policies (Maipose and Matsheka, 2007). And in Côte d'Ivoire (Kouadio Benie2007), Kenya (Mwega and Ndung'u2007) and Malawi (Chipeta and Mkandawire 2007), the agricultural background of early leaders helps explain their relatively supportive policies towards agriculture.

Group-identity rivalry

The sphere of influence on leadership extended significantly from the international arena based on the competing socialist and capitalist paradigms (Chapter 9), as well as from the professional or traditional background of leadership. It is interesting to note that although Botswana has been able to maintain a multiparty democracy, there has been one dominant party since independence, the Botswana Democratic Party (BDP) (Maipose and Matsheka 2007), suggesting that the lack of significant competition from the small parties probably helped to tolerate their existence.

Initial institutions

The economic rents generated by controls, for example, would often be redistributed on the basis of ethnicity and thus represent "rents to sovereignty" (Nkurunziza and Ngaruko 2007) or, alternatively, "rents to political survival". Furthermore, multilateral competition appears to have further exacerbated this form of redistribution in some African countries – e.g.

The role of government and time preference

Negative supply shocks

Moreover, these negative supply shocks led to significant deterioration in the terms of trade of many of the countries from the mid-1970s to early 1980s. However, both types of controls began to decline significantly from the mid-1980s, and by the early 1990s there was no trace of hard controls.

Positive supply shocks

However, the military's double-edged role became apparent, as it also overthrew incipient democratic governments with no-syndrome policies it deemed politically inappropriate. The military has also been used as a means of settling scores and grievances related to ethnic and other rivalries.

Political system

It is therefore encouraging to observe a significant increase in the frequency of syndrome-free status since the late 1980s in Africa. Matsheka (2007), "Indigenous Development Status and Growth in Botswana", chapter 15 in Benno J. O'Connell, Jean-Paul Azam, Robert H. Bates, Augustin Kwasi Fosu, Jan.