Tourism and Trails

Series Editors: Chris Cooper, Oxford Brookes University, UK, C. Michael Hall, University of Canterbury, New Zealand and Dallen J. Timothy, Arizona State University, USA

Aspects of Tourism is an innovative, multifaceted series, which comprises authoritative reference handbooks on global tourism regions, research vol- umes, texts and monographs. It is designed to provide readers with the latest thinking on tourism worldwide and push back the frontiers of tourism knowledge. The volumes are authoritative, readable and user-friendly, provid- ing accessible sources for further research. Books in the series are commis- sioned to probe the relationship between tourism and cognate subject areas such as strategy, development, retailing, sport and environmental studies.

Full details of all the books in this series and of all our other publications can be found on http://www.channelviewpublications.com, or by writing to Channel View Publications, St Nicholas House, 31–34 High Street, Bristol BS1 2AW, UK.

Tourism and Trails

Cultural, Ecological and Management Issues

Dallen J. Timothy and Stephen W. Boyd

CHANNEL VIEW PUBLICATIONS Bristol • Buffalo • Toronto

Timothy, Dallen J.

Tourism and Trails: Cultural, Ecological and Management Issues/Dallen J. Timothy and Stephen W. Boyd.

Aspects of Tourism: 64

Includes bibliographical references and index.

1. Culture and tourism. 2. Tourism–Environmental aspects. 3. Tourism–Management.

4. Trails. I. Boyd, Stephen W. II. Title.

G156.5.H47T564 2015

306.4'819068–dc23 2014025105

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue entry for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN-13: 978-1-84541-478-8 (hbk) ISBN-13: 978-1-84541-477-1 (pbk) Channel View Publications

UK: St Nicholas House, 31–34 High Street, Bristol BS1 2AW, UK.

USA: UTP, 2250 Military Road, Tonawanda, NY 14150, USA.

Canada: UTP, 5201 Dufferin Street, North York, Ontario M3H 5T8, Canada.

Website: www.channelviewpublications.com Twitter: Channel_View

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/channelviewpublications Blog: www.channelviewpublications.wordpress.com

Copyright © 2015 Dallen J. Timothy and Stephen W. Boyd.

All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the publisher.

The policy of Multilingual Matters/Channel View Publications is to use papers that are natural, renewable and recyclable products, made from wood grown in sustainable for- ests. In the manufacturing process of our books, and to further support our policy, prefer- ence is given to printers that have FSC and PEFC Chain of Custody certification. The FSC and/or PEFC logos will appear on those books where full certification has been granted to the printer concerned.

Typeset by Techset Composition India (P) Ltd., Bangalore and Chennai, India.

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Short Run Press Ltd.

v

Contents

Figures vii Tables xi Acknowledgements xv Preface xvii

1 Introduction 1

Introduction 1

Definitions and Meanings 3

Scope, Scales and Settings of Routes and Trails 8 Conclusion 15

2 Cultural Routes and Heritage Trails 17

Introduction 17

Purposes of Cultural Heritage Trails 18

Cultural Heritage Trails as Tourism Resources 20 Conclusion 57

3 Nature Trails and Mixed Routes 60

Introduction 60

Nature Trails 60

Mixed Routes 77

Conclusion 94

4 Demand for Trails and Routes 96

Introduction 96

General Trends in Demand 97

Characteristics of Trail Users 103

Access and Location 107

Trail Uses 110

Experience, Enjoyment and Satisfaction 112

Barriers to Use 121

Conclusion 124

5 Tourism, Recreation and Trail Impacts 126 Introduction 126

Type of Trail/Route Impacts 127

Conclusion 162 6 Planning and Developing Trails and Routes 164 Introduction 164 Route Designation and Related Policies 165 Planning and Developing Trails and Routes 179

Trail Design 196

Conclusion 212

7 Managing Routes and Trails 214

Introduction 214

Supply Versus Demand Techniques 215

Visitor Management Frameworks and Procedures 235 Conclusion 245

8 Reflections and Futures 247

Reflections 247 Futures 255 References 258 Index 296

vii

Figures

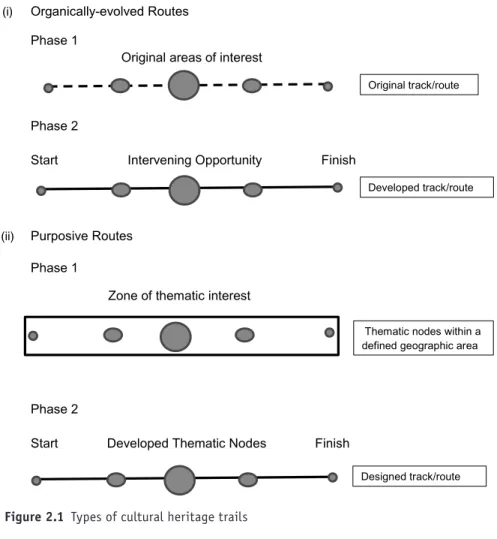

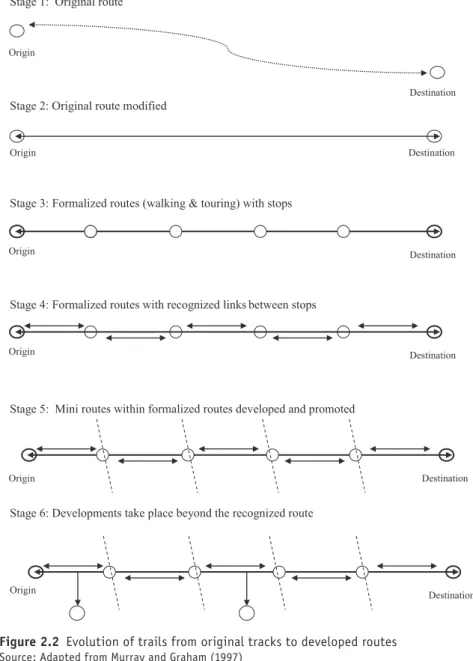

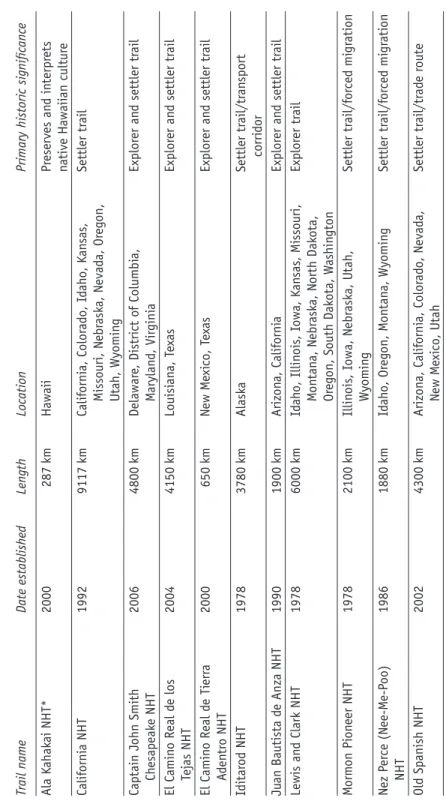

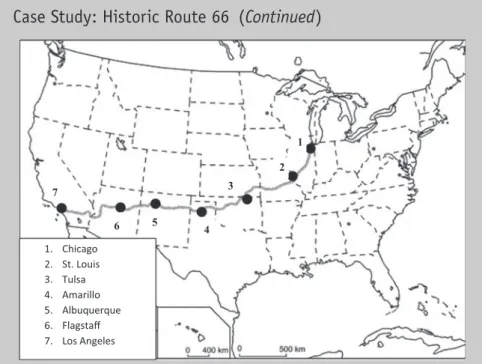

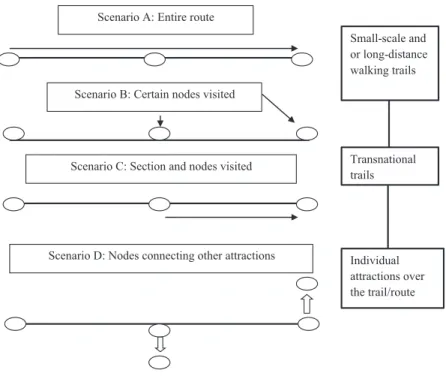

Figure 1.1 Conceptual model of trails and routes: A nested hierarchy 15 Figure 2.1 Types of cultural heritage trails 21 Figure 2.2 Evolution of trails from original tracks to developed routes 23 Figure 2.3 Route 66: Illinois to California 30 Figure 2.4 Sign marking the Way of St James in France 34 Figure 2.5 Way of St James and secondary routes 35 Figure 2.6 The historic Grand Canyon Railway 38 Figure 2.7 A small-scale navigable canal in the Netherlands 40 Figure 2.8 Paths at the archaeological site of Tulum, Mexico 44 Figure 2.9 A trail on the ancient city walls of Girona, Spain 45 Figure 2.10 One of Portugal’s wine trails 50 Figure 2.11 St Patrick’s grave in Downpatrick, Northern Ireland 55 Figure 2.12 St Patrick’s Trail/Christian heritage route with

recognized attraction clusters 56

Figure 2.13 The head of the Gospel Trail in Israel 57 Figure 2.14 Possible trail/route experience scenarios 59 Figure 3.1 A greenbelt trail in Scottsdale, Arizona, USA 64

Figure 3.2 A wilderness hiking trail in Utah, USA 65 Figure 3.3 A geology trail at Craters of the Moon National Park, USA 70 Figure 3.4 A rainforest canopy trail in Ghana 72 Figure 3.5 The Great Walks of New Zealand 75 Figure 3.6 A visitor center on the Appalachian Trail at Harper’s Ferry 76 Figure 3.7 A bicycle path crosses the Dutch-Belgian border at

Baarle Hertog/Baarle Nassau 80

Figure 3.8 A scenic byway marker in the US Southwest 83

Figure 3.9 The Causeway Coastal Route 87

Figure 3.10 The Causeway Coast visitor center 88 Figure 3.11 A popular rail-trail in Illinois, USA 91 Figure 3.12 Types of nature trails and mixed routes 95 Figure 4.1 RVs are popular along scenic routes and byways 104 Figure 4.2 England’s coastal path: Developing a new national trail 108 Figure 4.3 A rural footpath on the Isle of Man 109 Figure 4.4 Applying the realms of experience to trail participation 113 Figure 4.5 Factors shaping demand for trails and routes 124 Figure 5.1 The widening effect of off-trail use in the Himalayas

of Bhutan 128

Figure 5.2 Mount Robson Provincial Park as part of the

Canadian Rocky Mountains World Heritage Site 130 Figure 5.3 A vandalized agave plant along a heritage trail in Mexico 135 Figure 5.4 A squirrel waiting trailside for tourist handouts by the

‘do not feed the squirrels’ sign at the Grand Canyon 137

Figure 5.5 This trail is experiencing significant wear and tear,

and its railing is beginning to fail 138 Figure 5.6 The social effects of recreational noise 147 Figure 6.1 The Canadian Heritage Rivers System 168 Figure 6.2 Comprehensive trail development model 180 Figure 6.3 Hiking trail planning framework 182 Figure 6.4 Trail use of utility infrastructure (water works) in

Gilbert, Arizona 186

Figure 6.5 Urban heritage trail formalization: Options and

development process 193

Figure 6.6 Highway sign designating a long-distance heritage route 203 Figure 6.7 Blazes marking the Pyrenean Way trail along the

French-Spanish border 203

Figure 6.8 Boston’s Freedom Trail embedded in the sidewalks to

guide tourists along the path 204

Figure 6.9 A warning sign for trail users 205 Figure 6.10 An accessible beach trail in Denmark 209 Figure 7.1 A ‘hardened’ trail creates a more durable and protective

trail surface at this Greek archaeological site 220 Figure 7.2 An interpretive panel on Hadrian’s Wall Path, England 225 Figure 7.3 An unstaffed interpretive center on a scenic byway

in Australia 226

Figure 7.4 A ‘branded’ National Recreation Trail in Puerto Rico 231

Figure 7.5 The POLAR model 240

Figure 7.6 POLAR stages four, five and six: Units,

access and thresholds 241

Figure 7.7 Partnership models for landscapes of different

context and scale 245

xi

Tables

Table 2.1 Designated National Historic Trails in the US, 2013 26 Table 2.2 Examples of tourism-oriented heritage railways 37 Table 2.3 Top 15 wine producing countries in the world by volume, 2010 48 Table 3.1 National Water Trails in the US, 2013 69 Table 3.2 Characteristics of the Great Walks, New Zealand

(short–medium distance trails) 75

Table 3.3 European cycle routes in the EuroVelo program 81 Table 4.1 Five most popular outdoor activities in the USA by

participation rate, 2011 98

Table 4.2 Five most popular outdoor activities in the USA by

frequency of participation, 2011 98

Table 4.3 Trends in demand for trail-type water activities,

2006–2011 (in thousands) 99

Table 4.4 Selected activities in England performed in free time

by age, 2007–2008 99

Table 4.5 Top 10 active sports by gender in England, 2007–2008 100 Table 4.6 Pilgrims’ mode of transportation on the Way of

St James to Santiago de Compostela 101

Table 4.7 Top 15 nationalities completing the Camino de

Santiago, 2012 102

Table 4.8 Geographic and demographic characteristics of

D&L Trail users 105

Table 4.9 Trail use characteristics of D&L Trail users 106 Table 4.10 Economic distinction between goods, services

and experiences 112

Table 4.11 Mean importance ratings for factors influencing

a route choice 115

Table 4.12 Desirable attributes of a scenic byway 118 Table 4.13 Top 15 reasons people enjoy scenic byways 119 Table 4.14 Motivations and user type of a suburban all-purpose trail 119 Table 4.15 Motives and influential factors for hiking the

West Highland Way, Scotland 120

Table 5.1 The amount and severity of types of ecological impact

on Berg Lake and Mount Fitzwilliam Trails 132 Table 5.2 Frequency and lineal extent of problem areas for

Berg Lake and Mount Fitzwilliam Trails 132 Table 5.3 Mean ratings of trail photos by tourists and residents

in and near Lom, Norway 140

Table 5.4 Landowners’ concerns before the Katy Trail pilot

sections opened 142

Table 5.5 Changes in landowners’ attitudes 144 Table 5.6 Noise impact cases above the 25% threshold 148 Table 5.7 Observed behavioral events on Jefferson County open

space trails 150

Table 5.8 Spending patterns of cyclists on the north-east

England section of the North Sea Cycle Route 156 Table 5.9 Annual use and expenditure estimates for the D&L Trail 158

Table 5.10 Lodging choice of multi-day users on the D&L Trail 158 Table 5.11 Use of the D&L Trail influenced people’s

equipment purchases 159

Table 5.12 Purchases of ‘soft goods’ while using the D&L Trail 159

Table 6.1 European Cultural Routes 167

Table 6.2 Chronological development of the Canadian Heritage

Rivers System 170

Table 6.3 Trail objectives and rationale within UK local

cultural strategies 178

Table 6.4 Rationale behind the development of the Thornbury

Millennium Trail, UK 179

Table 6.5 Business responses to association with the Art Deco

Trail, Napier 196

Table 6.6 Acadia recreation setting attributes and encounter levels 201 Table 6.7 Little Moose Island (LMI) and Jordan Pond (JP)

respondent preferences regarding management of use

and trail hardening measures 202

Table 7.1 Visitor management techniques 215 Table 7.2 State regulation on commercial horseback tours in

National Parks, Australia 218

Table 7.3 The seven principles of Leave No Trace 222 Table 7.4 On-site key messages to encourage minimal impact on

the Cape Split Trail 223

Table 7.5 Summary of funding preferences of North Carolina

paddlers more likely to support funding mechanisms 233 Table 7.6 Summary of funding preferences of North Carolina

paddlers less likely to support funding mechanisms 234 Table 7.7 Summary of preferences of North Carolina paddlers

who view paddle trails as an economic development tool 234

Table 7.8 Comparison of the opportunity setting classes and management factors for the ROS, TOS and ECOS

frameworks 237

Table 7.9 Scottish Great Trails 243

Table 8.1 Researchers’ interest in tourism trails and routes over time 248

xv

Acknowledgements

I express deep gratitude to Stephen for his patience with me and for his youthful energy and sleepless nights in finishing this manuscript. To my many friends and colleagues around the world, thank you for staying with me and for keeping me on the straight and narrow path. I am especially grateful to my four children, who are no longer kids but were when I started this book! I also wish to express gratitude to dear friends Doug and Marsha Jarman, Kent and Linda Barnes, and Glen and Renae Lukens for being patient as I put them firmly on the back burner until the book was finished. There shall be no more of ‘I can’t, I have a book to write!’ Finally, my deepest grati- tude goes to Carol, my forever sweetheart, who puts up with much and whose patience is never ending. I’ve been lucky enough to be her husband for 26 years. It has been the greatest honor and privilege of my life. We have journeyed far on life’s path together. I can’t wait to see what adventuresome trails await us in the next 25 years. I’m certain there will be many forks in the road, and as funnyman Yogi Berra once said ‘When you come to a fork in the road, take it.’

Dallen J. Timothy There are a number of people I wish to thank during the time this book was written. First I want to thank Dallen who has been both a friend and a col- league since we met as graduate students at the University of Western Ontario, all those years ago! I have enjoyed the ‘journey’ this book has taken us on. There are a number of other colleagues who I wish to thank who have been there for me at different stages of my academic career with advice and friendship: Dick Butler, Michael Hall, Alan Fyall, Brian Garrod, Richard Sharpley, Tom Hinch and Brian Wheeller. I want to thank my sons and step- sons who often inquired what topic I was now writing on; here’s hoping they will want to pick the book up and read some sections of it! I wish to also express my deepest love and gratitude to my parents, my sister and my brother, who worry too much that these writing projects take up too much of my personal time. I value their opinions and promise to improve my per- sonal life–work balance in the future. Finally, my deepest thanks and love

goes to Wendy, my wife, who has never questioned the hours that writing this book has invaded on our personal lives and time; it’s been a journey we have taken together and I am so appreciative of her enduring support for everything I do. This book talks about some amazing trails and routes, here’s hoping we get to explore many of them together in the not too distant future.

Stephen W. Boyd We both wish to extend our heartfelt gratitude for the entire team at Channel View Publications, especially for their unwavering patience and enthusiasm for the book, and Ellie’s gentle reminders. The Channel View team is truly composed of pure and honest professionals!

xvii

Preface

More than a decade ago we co-wrote a book titled Heritage Tourism (2003) for Pearson’s Themes in Tourism series. Some of our thinking then involved cultural routes, and one of the book’s main case studies highlighted a heri- tage trail. But the genesis of our interest in trails, routes, byways, footpaths and other linear corridors predates that book back to the time when we were both graduate students in geography at the University of Western Ontario, Canada. At that time, Dallen published an article in the journal Ontario Geography about the Nauvoo Road in the province of Ontario, which linked pioneers from Canada to the broader Mormon Trail in the United States.

Stephen was then the student editor of the journal, and the article sparked an interest in routes as part of tourism and heritage landscapes. The publica- tion of Wall’s (1997) simple, but useful, typology of tourism attractions as points, areas and lines started both of us realizing that of all three spatial arrangements, linear tourism forms received the least scholarly attention. In 1999, we co-presented a conceptual paper on linear tourism spaces at a con- ference in Flagstaff, Arizona, which was followed by a number of works on the topic.

In 2002, Stephen applied the idea of tourism corridor development to an urban trail in Mombasa, Kenya. In 2004, he co-presented a paper on urban heritage routes at a conference in Loch Lomond, Scotland, with one of his postgraduate research students from New Zealand. Over the past decade, Stephen has returned to writing about trails as part of invited chapters in edited books and cases in heritage and presenting research on the subject matter at conferences in Jerusalem and Valparaiso, Chile. Dallen, in his writ- ing over the past decade has also devoted considerable space and attention to trails and routes in many of his authored and edited books and journal arti- cles. As such, this book has been a journey for both of us given that our common academic interests and research backgrounds on trails and routes started to coalesce more than 20 years ago.

Apart from our stories and interests in trails and routes, a more serious reason emerged for the production of this book. Although a considerable volume of research has been done, particularly within the recreation domain much more so than in tourism, and very much resigned to case studies in

refereed journals, book chapters, or conference presentations, there has been no concerted effort as far as we are aware, until now, to bring all of these ideas together in an accessible book for students, academic researchers and practitioners.

Unlike many authored books, which often are part of a series of similar works, this book, in our opinion, is the first to devote a serious, comprehen- sive and holistic assessment of routes, trails, tourism and leisure. It builds on the recognized need for scholars to focus on narrower and more special- ized monographs, including in this case, a particular type of landscape and visitor attraction. We see this as a contribution to learners and teachers who are interested in cultural heritage-based tourism, recreation and leisure stud- ies, landscape and change, human mobility, geography, environmental man- agement, and broader interests in destination planning, development and management. We acknowledge limitations in this volume and perhaps also that linear spaces are not the most exciting topic for everyone, but we also believe that this seminal book on the topic provides a solid foundation for many years of fruitful research on one of the most omnipresent leisure resources on the globe.

Dallen J. Timothy Gilbert, Arizona, USA Stephen W. Boyd Newtownabbey, Northern Ireland January 2014

1

Introduction

Introduction

Trails and routes have been indispensable to travel and tourism over the centuries, helping to form the basis of mobility patterns of the past and the present. While they have been recognized elements of human landscapes, the contribution they have brought to tourism and recreation has been understated, hence the rationale for this book. Humans throughout history have blazed and utilized trails in their hunting, gathering, herding and trad- ing pursuits, among which were built established routes that would see explorers, traders, migrants, pilgrims and later tourists. In some geographic settings, certain defined trails and routes would become well-trodden and utilized by many subsequent generations, providing a foundation on which a distinct tourism product would emerge (Moore & Shafer, 2001).

Many of these original pathways became the foundations for the multi- tudes of modern recreation and tourist trails of today (Hogan, 1998;

Mulvaney, 2003). As well, some of the vast networks of contemporary highway systems are based upon footpaths and trails that were established centuries or millennia ago. Today, it would be hard to identify a region of the world which does not boast of a trail or route that is sold as part of a wider tourism or recreation experience. And yet, the attention given to this type of attraction has been, to date, minimal, except for some tangential mentions in broader studies or focused and descriptive case studies of either supply or demand. In short, there has not been a concerted attempt to bring together what is a rather disparate body of work by scholars on trails and routes; the book’s central aim is to address this lacuna. A useful starting point for the discussion is to examine the role that linear systems (e.g. paths, routes and trails) have played in assisting people to move around, including for purposes of leisure and pleasure.

Linear paths have long been an important tool for human mobility, and much of their appeal was associated as much with the pathway as it was with the destination to which it led. Hunting parties and traders were not required to reach a geographical goal. Instead, they often met the purpose

1

of their departure along the way. During ancient and medieval times, pre- scribed byways were developed and utilized for transporting goods and people from one place to another. Roads and other corridors were even paved and signposted during the Roman era. Ancient adherents to Buddha’s teach- ings traveled along pilgrim circuits to visit the places associated with his birth, ministry and death (Singh, 2011). Medieval Christian pilgrimage, the oft-labeled ‘forerunner of modern-day tourism’ (Olsen & Timothy, 2006), was also a heavy user of prescribed trails that not only led to the end goal, the place of miracles, but also functioned to cleanse, humble and test the faith of spiritual sojourners with their arduous topographies and their great distances. The Grand Tour of Europe, from the middle of the 16th century to the early 19th century, popularized a certain ‘route’ or journey through many of the capital cities of antiquity and culture, which remains popular with today’s circuit travelers of Europe. Following the writings of early Grand Tour travelers came pre-ordained routes some would follow, includ- ing picturesque tours of England and Scotland (Aitchison et al., 2002;

Towner, 1985).

Today, linear corridors are still important for travel both as transporta- tion passageways and as attractions and resources for tourists and recreation- ists. One of the most pervasive types of tourism and recreation attractions today is trails, pathways and scenic routes and corridors. They provide a wide range of cultural and nature-based opportunities, which many com- munities and regions throughout the world are beginning to capitalize on and promote in their marketing efforts (Fai, 1989; Reader’s Digest, 2005; Yan et al., 2000). In most cases, trails and routes are seen by destinations as a tool for conserving natural and cultural environments, involving community members in decision-making, earning more tax dollars and regional revenue, and improving the quality of life of residents through employment and the development of a resource they too can utilize for their own enjoyment or transportation.

Trails have even secured some prominence in popular culture among modern-day travel writers and explorers. Michael Palin, for example, has not only created ‘new’ routes but rather taken the world on journeys from pole to pole, in circumnavigating the Pacific Rim, in crossing the Sahara, and forging pathways through Brazil, thereby opening new possibilities of circular and linear routes, pathways and journeys that today’s traveler may try to emulate to varying degrees. Similarly, the satirical writing of Bill Bryson in his novels Notes from a Small Island, Down Under and The Lost Conti- nent, has allowed modern-day travelers to re-create portions or all of his journeys across Britain and Australia, and through small-town America, respectively, thereby reinvigorating for many the route or journey over the destination. Perhaps the best example of Bryson focusing on an established route or trail is his experience of walking parts of the Appalachian Trail, renowned as the longest footpath in the world, in his work A Walk in the

Woods. The Appalachian Trail was established as early as 1925 in an era where the rambling movement was gaining prominence. While the authors do not have the intention to entertain the idea of becoming travel writers about routes and trails, they do believe there is a serious ‘academic story’ to tell about routes and trails and the journeys people have taken on them throughout history.

This first chapter starts the ‘journey’ by providing an overview of types of linear resources that are important tourist attractions and recre- ation resources and examines different types of trails, their role in the attractions system and important matters of scale that help define linear routes and trails. It is important at the outset of the book to provide useful definitions and meanings to what can be termed a ‘trail’ and a ‘route’.

Following this, a typology of linear spaces is presented on other corridors that are important trails and routes, namely paths, bridleways, greenways and tour circuits.

A discussion of the scope, scale and settings of trails and routes is next.

Tourism attractions and spaces can be points, areas or lines. This book focuses on lines, or linear resources, with the acknowledgement that point attrac- tions and small areas can also be part of wider linear spaces. With respect to scale, a discussion is then presented on trails and routes that range from what can often be termed mega trails (covering many thousands of kilome- ters) to very short walking trails. The various settings of routes and trails are introduced, forming the basis of more in-depth discussions in later chapters on heritage, nature and mixed trail corridors in both urban and rural con- texts. The chapter concludes by introducing a conceptual model around which the book and its contents are shaped. This model takes into consider- ation the supply and demand features of routes and their settings, scales, types, managerial structures and their wider macro policy environment.

Defi nitions and Meanings

The aim of this book is to look holistically at all types of human-created or human-delineated linear routes, although the meaning of each of these might differ depending on the location of the trail, its size and scale, and the types of resources being linked and utilized. The purpose of this section is to establish the types of trails that exist within the recreational and tourist attractions realm and to provide an explanation of each of these and their overlapping or diver gent meanings.

Routes and trails

A trail is essentially a visible linear pathway of many varieties, which is evident on the ground and which may have at its roots an original and

historical linear transport or travel function. A route, on the other hand, is generally more abstract and often based on a modern-day conceptualization and designation of a circuit or course that links similar natural or cultural features together into a thematic linear corridor. Scenic routes, or scenic roads, have become more important since the 1980s. These are designated roads and highways that pass through picturesque natural and cultural areas that would be of high aesthetic value to passersby (Schill & Schill, 1997).

Scenic routes often follow natural features such as mountain ranges or coast- lines and can invoke awe or nationalist sentiments as they focus on national symbolisms and national identity (Faggetter, 2001).

There is a wide range of definitions of the term ‘trail’, depending on which agency or individual is defining it and for what purpose (Jensen &

Guthrie, 2006; Moore & Ross, 1998; Moore & Shafer, 2001). Most outdoor recreation-oriented definitions emphasize corridors in protected areas and other natural or cultural settings meant for foot, bicycle or horse traffic;

these definitions often exclude motorized vehicle access and use, although there are many recreational trails that are specifically devoted to motorcycles and other off-road vehicles. The definition of trails used in this book is some- what broader and includes all natural or human-made linear corridors in rural or urban areas designated as trails, paths or routes for the use of recre- ationists, tourists or travelers regardless of their mode of transportation.

Thus, our description involves multiple scales and goes beyond purely a natu- ral area definition to include cultural areas, cities, the countryside and other forms of transportation besides foot or bicycle.

In the United States (US) the National Recreation and Park Association classifies trails as greenway trails, park trails and connector trails, which link parks to work places and schools (Moore & Shafer, 2001: 4). Moore and his colleagues (see Moore & Driver, 2005; Moore & Ross, 1998; Moore & Shafer, 2001) provide a comprehensive overview of several types of linear resources, although their examination focuses overwhelmingly on outdoor nature trails and is not comprehensive from a tourism and cultural heritage perspective.

As well, these classifications tend to be quite Americocentric and do not deal directly with issues of scale, resource utilization or the nuances of demand.

Nonetheless, theirs is a useful starting point in understanding the wide vari- ety of trails that are used by tourists and recreationists. Their typology, which includes traditional backcountry trails, recreational greenway trails, multi-use trails, water trails, and rail-trails, will be examined in much more detail in later chapters.

At first glance the title of this book might appear confusing to some people, depending largely on where they live and their own exposure to linear tourism and recreation resources, such as trails and scenic corridors.

The terms trail, path, walkway, corridor and other similar words have differ- ent meanings in different locations. A footpath in the United Kingdom (UK), for example, usually refers to small ways in urban or rural areas that are

relatively accessible and short in length. Such a phenomenon in the US would more commonly be referred to as a trail. Despite some differences, for ease of discussion, this book uses the words trail, corridor, route, path and others interchangeably to encompass all forms of linear, human-designated attrac- tions, even though the authors are cognizant of many subtle and not so subtle differences between different terms. While recognizing this treatment of terms, the following sections set out to define other linear recreation and tourism corridors that are an important part of the global system of routes and trails.

Paths and bridleways

Paths, footpaths and tracks usually indicate narrow walkways that have been trodden or beaten by humans, animals, bicycles or other agents. They are a type of trail typically found in wilderness and rural areas, although many footpaths have also been labeled in towns and cities, frequently in parks or along streams and canals. Paths are used for recreational purposes, such as countryside strolling, or for transportation in towns or between vil- lages. Bridleways or bridle trails are similar to pathways, except that they may also be used to ride or lead horses, and some bridleways are devoted solely to horseback riding (Beeton, 1999a; Countryside Panel, 1987).

Right of way is a related term more common in the UK and Europe than in North America or other parts of the world that refers to open-access paths that the public has a legal right to use at any time (Natural England, 2012;

Wolfe, 1998). Rights of way in England are classified as footpaths for walk- ing; bridleways, where horse riding and cycling are allowed in addition to walking; and byways, which are open to all traffic (Walker, 1996). The Countryside Commission, which was subsumed in 1999 and its responsibili- ties spread to other nature and rural agencies, had as its original purpose promoting public rights of way to develop ‘networks of well signposted and maintained routes throughout the countryside, giving ready access from towns, linking points of interest in the countryside, and coordinated with accommodation, car parks, publicity and guides’ (Walker, 1996: 28). In addi- tion to rights of way paths, according to the Countryside and Rights of Way Act 2000, the public is permitted to walk freely on mapped rural areas with- out having to remain on prescribed paths. At their disposal is approximately 865,000 hectares of open-access land (Natural England, 2012), which has opened up considerable debate in the UK and paved the way for more ram- bling options for day trippers and tourists.

There are several different official scales associated with rights of way.

In 1989, the Countryside Commission in the UK established parish paths and community paths, local walks and rides, regional routes and national trails. The first type, parish paths and community paths, were marked from roadways and noted on ordinance survey maps. They were to be

maintained and kept opened, but not promoted or interpreted, for their primary users: local residents wishing to wander about the countryside.

These trails link local other trails or local roads to nearby villages, farms or churches (Curry, 1997; Walker, 1996). Local walks and rides were also marked and maintained but promoted for local use near people’s homes or in their holiday destinations. Car parks were provided, and many bestowed a full day’s range of hiking and other activities. Local walks can be found not only in rural areas but also in cities where they often have a cultural or historical bent. Regional routes are longer, themed routes that could require one or more days of travel and could be promoted as important tourist attractions, especially for domestic visitors. Finally, national trails (known as ‘long distance routes’ in Scotland) are long-distance corridors in England and Wales that are truly national in character, can be used on multi-day hikes by foot, horse or bicycle, and can be marketed as interna- tional tourist attractions (Curry, 1997; National Trails, 2012; Walker, 1996). Presently there are approximately 4000 km of national trails in England and Wales.

Greenways

Greenways are different from trails, although many greenways include recreational or transportation trails within them, and they often connect traditional parks and trails (Bowick, 2003; Moore et al., 1998; Mundet &

Coenders, 2010). Little (1990) advocated for a very comprehensive definition of greenways, which included among its various manifestations the trails defined above. According to Little (1990: 1), greenways can be viewed rather broadly to include linear open spaces along natural corridors (e.g. rivers or ridgelines) or human-created features (e.g. railways, scenic roads, canals);

natural or landscaped courses for bicycle or pedestrian use; open-space con- nectors that link nature preserves, parks and historic sites to one another or to populated areas; and linear parks specified as parkways or greenbelts.

Little also recognized five specific, albeit overlapping, kinds of greenways based upon their location, their settings and their functions: urban riverside greenways, recreational greenways, ecologically important natural corridors, scenic and historic routes, and comprehensive greenway networks. Other observers have provided similar definitions and classifications, such as Fabos (1995), who defined greenways as linking corridors of various sizes and sug- gests a threefold typology: recreational greenways, ecologically significant greenways and heritage or cultural greenways. Much work on the subject has emphasized the role of greenways and their functions in urban areas. These include, but are not limited to, recreation, transportation routes, economic development, wildlife habitats, general beautification and storm-water management (Frauman & Cunningham, 2001; Jim & Chen, 2003; Moore &

Shafer, 2001; Palau et al., 2012).

Tour circuits

Tour circuits are another type of route that has been largely overlooked in the travel literature. These courses are important in understanding tourism growth, regional dynamics and linkages, as well as traditions of market demand for a region and its products. While these are not designated, or offi- cially recognized, linear routes as the trails and pathways heretofore discussed are, they are still important in that they are circuits that have evolved over the years into preferred networks that are traveled independently or on a coach and tour package. Backpackers and other independent travelers have com- monly followed popular routes in different parts of the world. Drifter tourism has mythologized places and generated a ‘mobile subculture of international backpackers [who utilize] an almost entirely separate tourism infrastruc- ture . . . [and] follow distinctive trails of their own’ (Westerhausen & Macbeth, 2003: 71). Many of these ‘Gringo trails’ or ‘Hippy trails’ can be found all over the world, but particularly in developing regions (Hampton, 2013).

‘Drifting’ through Southeast Asia is popular among backpacker tourists on three to six month journeys. Among the most favored backpacker destina- tions on these travel circuits are Bangkok, Koh Samui, Koh Phi Phi and Chiang Mai (Thailand); Luang Prabang, Vang Vieng and Vientiane (Laos);

Hanoi, Dong Ha and Hué (Vietnam); Phnom Penh and Siem Reap/Angkor Wat (Cambodia); and Penang, Pangkor and Kuala Lumpur (Malaysia) (Backpacker Guides, 2012). These are all considered ‘must-do’ destinations on the Southeast Asian backpacker circuit and include a mix of culture, nature and beaches. Similarly, a popular drifter/nomad circuit in Australia is known as the Harvest Trail, where backpackers travel around the country along known circuits, harvesting fruit and vegetables when they come in season in exchange for cash, places to sleep and food to eat (Cooper et al., 2004). This is touted as a work-as-you-go method of traveling and seeing Australia. Likewise, the ‘Hummus Trail’ is an informally prescribed network of sites, cities, villages, guesthouses and restaurants that are frequented by Israeli youth traveling through India and where there are many services catering specifically to the Israeli market. This provides a sense of solidarity among Israeli backpackers and in some ways provides the comforts of home in a very different environment (Enoch & Grossman, 2010). The medieval Grand Tour is sometimes said to be the ancient forerunner to today’s backpacker tourism; Grand Tour circuits also included well-trodden tour cir- cuits and must-see destinations in Italy (e.g. Rome, Venice, Florence and Naples) and other parts of Europe (Brodsky-Porges, 1981; Towner, 1985).

In addition to backpacker routes, there are also recognized tour circuits used by tour companies and individual travelers on a regular basis and these take on many spatial forms including day trips, route trips, and multi-nodal trips (Zillinger, 2007). Many of these are based on point-to-point networks of capital cities, and in most cases these link together famous sites that are

known to appeal to mass tourists. Common tour circuits in Western Europe include visits to Amsterdam, Brussels and Paris in conjunction with London and Rhine River cruises. Attendance at the once-a-decade passion play at Oberammergau, Germany, is usually accompanied by visits to the salt mines at Berchtesgaden and nearby Salzburg, Austria. Another emerging trend is Christian pilgrimage cruises that follow the routes of ancient apostles throughout the Mediterranean. Thousands of such unofficial, albeit popular, tour circuits exist all over the world. However, they are not the main focus of this book, although they will be alluded to throughout.

Scope, Scales and Settings of Routes and Trails

Tourist attractions are the most important part of the tourism system, for without them people would have no place to go. Attractions include a wide range of resources, both natural and human-created, that draw people away from their home environments to undergo a wide range of potentially overlapping experiences, including pleasure and enjoyment, relaxation, edu- cation, cultural edification, religious obligation, spiritual inspiration, health and wellness, nature appreciation or the discovering of one’s roots (Gunn &

Var, 2002; Leiper, 1990; Lew, 1987).

Several scholars have examined the meanings and forms of tourist attrac- tions, suggesting that attractions are more than simply any object, place or event that draws people. Leiper (1990; see also Hall & Page, 2010) used a systems approach to deconstruct the meaning of attractions and suggested that they are more than simply a specific site that exudes some sort of intrin- sic value. Instead, he (and MacCannell, 1976) suggested that tourist attrac- tions comprise the point of attention itself (the nucleus), the tourists who visit them, and markers, or the information provided. Thus, for an object, event or place to become a tourist attraction, it must be valued, desired, pre- served and somehow its story interpreted by human beings. In this sense human value is assigned to it, and it becomes an attraction because of the human and informational/marker influences.

Another pertinent way of looking at attractions is by their areal or spa- tial form and function, remembering that tourism takes place not only at tourist attractions but also between them (Fagence, 2011; Zillinger, 2007).

Wall (1997) suggested a spatial-form typology of tourist attractions that is useful in understanding a site’s locational elements and possible physical impacts resulting from tourism, as well as being helpful in physical planning and developing commercial enterprises. He outlines three structural forms of attractions, namely points, areas and lines. Point attractions, according to Wall, are those where high numbers of people are concentrated in a small space to view and experience a single resource or a compact collection of connected resources. Some examples of point attractions include museums,

cemeteries, churches, waterfalls, monuments and archeological sites. The compact nature of points provides more efficient opportunities for the ‘com- mercial exploitation’ of tourists, and some of the negative impacts associated with tourism can be limited to small areas. Nonetheless, such areas may face the danger of being over-commercialized and overcrowded, which can at peak times diminish the quality of the visitor experience and result in envi- ronmental degradation.

National parks, small towns and historic cities, resort communities and wilderness zones are common examples of area attractions. This type of attraction might comprise several point attractions, such as scenic overlooks, waterfalls, campgrounds and historic buildings, which together become nodes in a larger attraction system. This resembles closely what Leiper (1990) called

‘clustered nuclei’, where tourists gather in certain areas because of the nucleic clusters of unifying themes. While areas might also attract large numbers of tourists, owing to their larger spatial extent, they can encourage a wider dis- persion of visitors, thereby spreading commercial development and tour- ist expenditures to more locations and diluting the negative impacts of heavy levels of visitation. Nonetheless, they, too, can experience extremely crow- ded conditions during high season. In many US national parks, such as Yellowstone, Zion, Grand Canyon and Great Smoky Mountains, excessive car traffic can make navigating park roads and car parks very difficult during the summer months (Sims et al., 2005). Wall (1997) suggests that some areas are so large and dispersed that it might be necessary to create concentrations of services that will enable visitors to be monitored, catered to and counted. This often takes place at gateways, interpretive centers and commercial clusters.

The final spatial type of attraction noted by Wall is of most concern in this book, although all three categories are important in the context of small- and large-scale routes and trails. Wall (1997: 241) defines linear tourism resources as those with physical linear properties and those which guide visi- tors along a specific path. These include rivers, lakeshores, coastlines, other rectilinear landforms, trails, highways and scenic routes. In these cases, visi- tors converge along narrow strips of land or transportation corridors. While users might be concentrated along linear attractions, they are more dispersed than at point attractions. Wall (1997: 241–242) suggests that from a mone- tary perspective, visitor concentrations may still be ample enough to attract substantial commercial development, which can have negative implications, such as overdeveloped coastlines, polluted rivers and byways cluttered with billboard advertisements. In some cases, scenic corridors are so crowded with buildings, pedestrians and car traffic that it is difficult to catch a glimpse of the natural or cultural landscape that was the primary appeal of the area.

Scale is a critical concept for understanding tourist attractions, destina- tions and tourism planning and development (Shackley, 2003). Different scales or sizes of routes and trails will have different management implications and conservation challenges. This spatial dimension is a crucial element of Lew’s

(1987) conceptualization of tourist attractions and their physical sizes and layouts. Lew suggested that attractions may range from very small objects, such as a famous piece of jewelry (e.g. the Hope Diamond), to very large areas, such as regions or countries. From the perspective of regions or countries, attractions tend to be multi-nucleic with an area possibly containing many examples of a type of attraction. One example is the common elements of the cultural or physical landscape that makes the Scottish Highlands appealing to many tourists (Leask & Barriere, 2000).

Another way of viewing scale is the expanse of an attraction’s reach in relation to visitors’ personal connections to, or interest in, the site or object (Graham et al., 2000; Gunn & Var, 2002; Timothy, 1997). Timothy (1997) suggested a scalar typology of cultural heritage attractions, with global attractions exerting the greatest appeal and impact to the most widespread consumer cohorts. These include famous sites that are recognizable and iconic throughout the world, some of which have been designated World Heritage Sites by the United Nations Economic, Social and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). Examples are the Great Wall of China, the Egyptian Pyramids, the Eiffel Tower and the Roman Coliseum. Just below global heritage sites are national attractions that appeal primarily to domes- tic travelers, but which may in fact also draw international visitors who are already in the destination. These often include nationalistic monuments and national shrines. Local heritage is one scale lower and appeals primarily to local visitors who may use historical museums, historic schools or monu- ments erected to local war heroes. At the smallest scale are attractions that appeal to individuals and families because of their personal connections to the place or event being visited. Old homesteads, cemeteries, churches, gene- alogical libraries, and other such attractions form the individual nuclei within a destination that is closely connected to one’s ancestral past (Timothy, 2008).

Although both of the contexts of scale noted above are critical ele- ments of understanding tourist trails and routes, the most obvious scale rela tionship is size in terms of distance and reach. Equally important are the geographical settings for trails, particularly urban and rural, or wilderness and developed.

If size and reach are examined on a continuum of small to large, one of the smallest trails would certainly be the course within a point attraction, such as a museum, garden or archaeological park (MacLeod, 2004). Such attractions are usually edged and crisscrossed with walkways or marked routes that help traffic flow and visitors proceed logically from one point or nucleus to another. These lines are important management tools in that they help interpreters and other site managers control crowds and disseminate interpretive information more effectively. These paths can help visitors build chronological knowledge and increase their expectations as some routes build up to a grand finale or anchor attraction within a garden or museum.

Further along the continuum are footpaths that lead from one attraction to another or one site to another within larger areas, such as national parks or historic villages. This also includes short nature trails, which visitors can follow into a rainforest, a dune, or short distances from a campground in the mountains. Such trails might be less than one kilometer long to a few kilo- meters long and are found abundantly all over the world. Usually these are limited to foot and bicycle traffic, although in some areas they might allow horses as well.

Larger in scope are extensive urban themed trails or tour circuits that link historic sites, buildings and locations associated with an important period of time, a famous person, an architectural style or a significant event (Goodey, 1975; Timothy, 2014). The ‘Gaudi Trail’, better known as the ‘Modernist Walking Tour’ of Barcelona, Spain, links the modernist architectural achieve- ments of Antoni Gaudi that have helped to make the city one of the most visible cultural centers of Europe (Usón, 2002). The New Amsterdam Trail in downtown Manhattan highlights the original locations of buildings and sites during the 17th-century Dutch colonial period of New York City (US National Park Service, 2009). Many of these trails can be traversed on an individual basis, or guided tours can be purchased or otherwise arranged. The US National Park Service provides an audio tour free to download onto mobile recording devices, while many of Barcelona’s visitors hire a city guide to pilot them through the architectural landscape of the city.

Regional and national trails tend to be large in scale, or long in length, but their actual sizes vary from country to country, and depending upon what they commemorate. What they all have in common, however, is significant size in relation to national territory, and they have cultural, historical or natural significance for the region or nation. Many such routes can only truly be followed by car owing to their length. These are common in Australia and North America, where many long-distance national trails parallel major high- ways, and distances are vast. In Australia, Northern Queensland’s Taste of the Tropics Food Trail and the Southern Heritage Drive are good examples of regional trails that focus on agriculture and culinary heritage (Australian Tropical Foods, n.d.; Cairns City Council, n.d.). Many shorter national trails are footpaths where only hiking and rambling are allowed, despite their lengths. Owing to its large size, the US is home to several important long- distance trails that have been officially designated National Historic Trails, National Scenic Trails or National Recreation Trails (Chavez et al., 1999;

Elkinton & Maglienti, 1994). It should be noted, however, that there are sev- eral shorter trails in the US that have the same designations owing to their national significance. The California National Historic Trail is the longest in the US trails system (9117 km) and traverses 10 states from The Midwest to the west coast. It is an emigrant trail that commemorates the westward movement of Europeans and the settlement of the west. The Appalachian Trail is one of the world’s longest nature trails (3500 km) and one of the most

heavily hiked in the US, although relatively few people navigate its entire length, instead joining it somewhere along the way and hiking for a few days at a time (Foresta, 1987; Hill et al., 2009). The National Trails system in the UK includes primarily long-distance footpaths and bridleways. Hadrian’s Wall Path (135 km) is one of the most popular national trails in England and extends from the west coast to the east coast in the north of the coun- try. It follows the old Roman frontier built nearly 2000 years ago. The wall and its parallel path pass through some of the most scenic landscapes of northern England. The path is popular for ramblers and drive tourists, the latter tending to stop at various locations, forts, turrets and interpretive centers along the wall (Coleman, 1994; McGlade, 2014; Usherwood, 1996).

Beyond the regional or national scale, there are many binational or mul- tinational routes that have become the focus of tourism promotional efforts (Timothy, 2014; Wanalertsakul et al., 2011). In most cases, these are desig- nated because of their cultural characteristics and the human elements of the past they purport to connect across international boundaries. Sometimes, although these link places in more than one country, they might be of a shorter length than completely domestic trails. One example is the 40 km Cross-border Mining Education Trail (Grenzüberschreitender Bergbaulehrpfad/

Prˇíhraniční naučná hornická stezka), shared by Germany and the Czech Republic to interpret the tin mining heritage of Central Europe. The route connects monuments, mines, ditches and tailings, museums and other attractions into a loop route that can be driven part of the way or walked entirely, crossing the German-Czech border twice (Kowalke, 2004).

Short international trails such as this one can be found by the thousands in all parts of the world (e.g. Koščak, 1999; Rennicke, 1997a). There are, however, larger routes that include many different countries. In some cases it is almost impossible to negotiate the entire route because of its sheer scale, the complexity of its connecting sub-trails, or because of political or physical geographical barriers. In several instances, travelers can follow the general direction of the trail or at least one branch of it by airplane, bus, train, private car, or a combination of these. Perhaps the best example is the Silk Road, which passes through the territories of several countries in Asia and Europe (Tang, 1991; World Tourism Organization, 1996). China, Kyrgyzstan, Turk- menistan and Uzbekistan are among the most active countries seeking to inscribe the route and some of its related sites on UNESCO’s World Heritage List in a truly transnational way. The Silk Road is not one single corridor but rather a wide network of ancient land- and sea-based silk trade routes that crisscross Central Asia, South Asia, the Middle East and the Mediterranean.

With the recent opening of a cargo train line from western China to Germany, in theory one of the main corridors of the Silk Road can now be traveled (Mu, 2011). Other large-scale routes have been proposed, including La Ruta Maya to connect the Mayan lands of Mexico and Central America as a cul- tural swath for preservation and economic development (Ceballos-Lascuráin,

1990). Aside from the Silk Road, one of the most ambitious proposals has been the development of the Cape to Cairo corridor, originally conceived by Cecil Rhodes to unite Africa by rail from its southernmost tip to its northern edge, from Cape Town to Cairo. In the past decade there have been whisperings of trying to resurrect this idea as a pan-African tourism corri- dor, although there are many physical, economic and geopolitical constraints standing in the way of its fruition (Frost & Shanka, 2001).

Some of these same multinational routes are well suited as walking paths, at least portions of them are. The Way of St James (Camino de Santiago) is one of the most popular pedestrian trails in Europe, especially among Roman Catholics. The main portion of the way begins in France and ends 900 kilometers later at Santiago de Compostela, Spain. In addition to the core trail there are feeder paths from as far away as the Czech Republic, Germany, Austria, Italy, Switzerland, Portugal, and several other European countries (Mariñas Otero, 1990; Santos, 2002). The Camino is a good exam- ple of true cross-border cooperation in developing a long-distance cultural/

pilgrimage trail.

Settings

As noted throughout the discussion so far, trails are found both in urban and rural settings with many overlapping purposes and resources. None- theless, this section examines some of the characteristics of each of these geographical settings. With respect to urban trails, they are often an integral element of the open space of cities and are increasingly frequented by urban residents. As for rural trails, they have become key access routes, often through landscapes of mixed ownership, as well as playing an important role in helping to conserve the countryside and open it up for passive forms of recreation and tourism.

Trails and walking paths are one of the most important elements of city tourism and recreation in the developed world, and they are becoming a more vital part of the urban milieu in the developing world. Urban trails provide much-needed open space in large cities and can be a respite from the frenetic pace of metropolitan living. They provide venues for exercise, trans- portation access between home and work or home and school, and help build an appreciation for the city and its history and nature.

The forms and functions of urban trails vary considerably from place to place and can depend on the age and size of the city, as well as the needs of its residents. City parks, gardens and other greenways are one of the most ubiquitous locations of urban paths and trails (Auckland City, 2004; Belan, 2000). They are now a universal part of the urban fabric of most historic cities throughout the world. Heritage trails are often developed to link together thematic cultural sites that are of most importance in the city where they are located (Goodey, 1975; Hayes & MacLeod, 2007, 2008).

In rural areas, trails, footpaths and other countryside corridors are usu- ally seen as potentially lucrative from a number of perspectives. First, they can be seen as being a salient tool for conserving rural landscapes via policy directions and building awareness and appreciation through interpretation and experience among the general public. In this sense, many public and quasi-public agencies that oversee rural trails view their designation and maintenance as crucial tools for capacity control, preserving the rural idyll and creating an appreciation for the exurban way of life (Gilbert, 1989). Most rural trails can be found in national parks or other protected public lands, although in the UK and other parts of Europe, they are very common on private land as well, with right of access laws allowing the public onto pri- vate lands for walking and hiking (Millward, 1993; Scott, 1986; Wolfe, 1998).

There is considerable overlap between urban and rural trails, as many of them lead from the countryside into cities or towns and vice versa, especially if they are found within the peri-urban space which is often referred to as the rural–urban fringe.

Networks

Another concept in understanding long-distance trails, large-scale travel corridors and international routes is networks. Networks are defined by rela- tionships between entities, or nodes, and the structure of these relationships (Scott et al., 2008: 1). From a tourism perspective, network analysis has tra- ditionally focused on the various service providers and administrators within the tourism system and their inter-organizational relationships. The collab- orative affiliations, partnerships and interdependence within the broader tourism system are what constitute the notion of networks (Baggio &

Cooper, 2010; Baggio et al., 2010; Timothy, 1998b). Underscoring networks are collaborative principles such as trust, cooperation, working for the greater good, social capital development and social support. While network concepts in tourism studies do not necessarily refer to the spatial notion of nodes and linear linkages as already noted, they certainly can.

Networks are especially crucial in understanding scale but also in interpreting the development and operation of purposive cultural routes (see Chapter 2), as well as other types of trails. The development of a trail (linear resource) from a series of individual nodes (point attractions) requires the suc- cessful implementation of networks and social capital building. The Ale Trail in Canada, discussed later, is a good example of the importance of building network capital and common trust, and how these efforts sometimes fail.

Marketing and governance networks are especially important in the develop- ment of multi-nodal destination products (Beaumont & Dredge, 2010; Dredge &

Pforr, 2008; Pavlovich, 2003), including purposive trails, owing to the com- plexities of consensus and trust building, forming interdependence, policy development and maintaining the public image of these tourist routes.

Conclusion

The supply of trails is extremely difficult to measure, as is demand. The number of trails, pathways, scenic routes and other linear resources is impos- sible to quantify for a whole variety of reasons, such as the ways they are classified, their different sizes, intensity of use, surface quality, ownership and management, locations, or the multi-jurisdictional aspects of many cross-border trails (Moore & Shafer, 2001). The best we can do is categorize them so that they can be studied, evaluated and measured. Many are private, many are public, many are small, many are large, many are nature-based, many are culture-based, many are historical and many are of more recent vintage. Chapters 2 and 3 examine the supply side of tourism and recreation trails. What they all have in common, however, is theming where points along the trail are linked together, either as being representative of a period of time or illustrative of cultural or natural phenomena (Meyer-Cech, 2005).

Long-distance routes attract visitors to a set of historically important cul- tural attractions by creating an attractively linked themed product (Shackley, 2003: 13). Nature trails, or countryside pathways, are themed as connectors or recreation trails that provide access to nature for their users, and they commonly focus on a specific ecosystem.

This chapter has not attempted to highlight every size, scale or type of trail, path or tourist corridor but rather to provide an overview of the main types, forms and functions. A useful way to encapsulate trails and routes is through the use of a conceptual model. Conceptual models are abstractions of reality, but they also serve as a useful tool by which one can position any trail or route. The conceptual model shown in Figure 1.1 also acts as a frame

Wider macro-policy environment

Nature of Experience Seng: Wilderness/peripheral

Rural

Rural–urban fringe

Urban Type: Cultural

Nature

Mixed Heritage

Figure 1.1 Conceptual model of trails and routes: A nested hierarchy

of reference for the whole book, addressing key aspects which are addressed in separate chapters. The model is shaped around the concepts of type, set- ting, scale, management structure and the wider policy environment that has shaped tourism development and infrastructure within certain defined geographic settings.

The model has a nested hierarchical form, which has at its center the experiential dimension of tourists and recreationists engaging in trails and routes (either in a casual, purposive or accidental form) as part of a leisure experience or its totality, shaped around the necessary supply in terms of types of trails and routes (including paths, bridleways, greenways and tour circuits), their settings in which they occur (wilderness/peripheral, rural, rural–urban fringe and urban), the scale involved (mega, binational or multi- national, national, regional and local) and finally their rationale (culture and heritage, nature-based or mixed). These elements of the model are shaped by a range of factors such as the administrative structures imposed on how the trails are managed (single ownership, partnerships, top-down or grass roots) marketed (as part of a wider attraction mix, or exclusively as a primary attraction) and the impacts they face. All of this takes place within the wider macro policy environment for tourism and recreation in which trail/route development is only one element of national, regional and local policies.

All of the model’s elements are addressed in detail within the book, start- ing with types (supply) of trail and routes – the focus of Chapters 2 and 3.

These two chapters examine in detail cultural, nature-based and mixed routes and some of the contemporary critical issues surrounding them. On the flipside, demand for trails and routes is addressed in depth in Chapter 4, emphasizing the uses of trails, market characteristics and behavioral aspects.

The ecological, social and economic impacts arising from cultural and natu- ral corridor usage are the focus of Chapter 5, including positive and negative outcomes of trails from both community members’ and tourists’ perspec- tives. Chapter 6 highlights the planning and development of routes and trails, looking particularly at the macro policy arena in terms of designation policies, legislation, planning and design. The seventh chapter examines the management of trails once they have been established, addressing issues such as maintenance, visitor management and monitoring. Chapter 8 provides reflections on the main ideas brought out in the book and provides direction for future academic discourse on trails and routes.

17

Cultural Routes and Heritage Trails

Introduction

This chapter commences an examination of the component parts of the conceptual model introduced in Chapter 1. The focus of the chapter is the supply side of routes and trails, and in this case cultural routes and heritage trails, probably the most popular type of tourist trail. In short, these are organized ways for cycling, walking, driving or riding that draw on the cultural heritage of a region and provide learning experiences and visitor enjoyment. They are marked on the ground with signs or other interpretive media and on maps that help guide visitors along their course (MacLeod, 2004). Heritage routes and trails tend to be most prevalent in areas with already high levels of tourism and, while there are many heritage trails in the less-developed parts of Africa, Latin America and Asia (e.g. the Slave Route, the Inca Trail and the Silk Road), their preponderance tends to be in the developed parts of the world, particularly in North America, Europe, Australia, New Zealand and Japan. As a result, and given the availability of information and data, the majority of trails mentioned in this chapter are from the developed world. Where available, information is also presented about examples from less-developed regions. This emphasis on more affluent countries does not imply that these types of routes and trails do not exist elsewhere, or that other places are less important. It simply reflects a greater abundance of information and empirical examples.

There are literally thousands of cultural heritage-based routes in all parts of the world. Some are more famous and well-trodden than others, and they exist on many different scales. While this chapter cannot possibly examine all of them, or even mention them by name, it does highlight a multitude of major trends from the supply perspective and elucidates a number of heritage trails in considerable detail. Although both culture and nature trails are