683

Indonesian Journal of Rheumatology Vol 15 Issue 1 20231. Introduction

Osteoarthritis (OA) is the most prevalent form of arthritis affecting nearly 302 million people worldwide, and is one of the major causes of disability in the elderly.1,2 OA may impair knee, hand, and hip joints, damaging structures such as joint cartilage, subchondral bone, ligament, capsule, synovial tissue, and periarticular fibrous tissue.3 Risk factors of OA include age, gender, ethnicity, genetics, diet, obesity,

muscle weakness, strenuous physical activity, history of physical trauma, decreased proprioceptive function, family history of OA, and mechanical factors.4 These risk factors influence the progression of cartilage destruction and abnormal bone formation in OA.4 The degree of cartilage destruction corresponds to the pain and movement impairment experienced by the patients.4,5 Nowadays, although OA is no longer solely attributed to degeneration or aging, age still remains

Indonesian Rheumatology Association (IRA) Recommendations for Diagnosis and Management of Osteoarthritis (Knee, Hand, Hip)

Rakhma Yanti Hellmi1*, Najirman2, Ida Ayu Ratih Wulansari Manuaba3, Andri Reza Rahmadi4, Pande Ketut Kurniari5, Malikul Chair6, Ika Vemilia Warlisti1, Eka Kurniawan2, Harry Isbagio7, Handono Kalim8, Rudy Hidayat7, Laniyati Hamijoyo4, Cesarius Singgih Wahono8, Sumariyono7

1Rheumatology Division, Department of Internal Medicine, Universitas Diponegoro, Semarang, Indonesia

2Rheumatology Division, Department of Internal Medicine, Universitas Andalas, Padang, Indonesia

3Manuaba General Hospital, Denpasar, Indonesia

4Rheumatology Division, Department of Internal Medicine, Universitas Padjadjaran, Bandung, Indonesia

5Rheumatology Division, Department of Internal Medicine, Universitas Udayana, Denpasar, Indonesia

6Simeulue General Hospital, Sinabang, Indonesia

7Rheumatology Division, Department of Internal Medicine, Universitas Indonesia, Jakarta, Indonesia

8Rheumatology Division, Department of Internal Medicine, Universitas Brawijaya, Malang, Indonesia

ARTICLE INFO Keywords:

Hand Hip Knee

Osteoarthritis

*Corresponding author:

Rakhma Yanti Hellmi

E-mail address:

hellmisppd77@gmail.com

All authors have reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

https://doi.org/10.37275/IJR.v15i1.225

A B S T R A C T

Background: Osteoarthritis (OA) is the most common form arthritis in the world, and its prevalence is predicted to rise higher in the future due to increasing life expectancy and growing number of elderly population. With the emergence of new treatment options in the last several years, a better understanding of OA diagnosis and management is required by every physician in Indonesia. Methods: A panel of eight selected rheumatologists from the Indonesian Rheumatologist Association (IRA) developed recommendations based on key questions formulated by a steering committee from IRA. These recommendation materials were taken from several online databases such as PubMed, Science Direct, and Google Scholar. Level of evidence and grades of recommendation were then assigned, and each member of the panelist team will assign a score to express their level of agreement. Results: A total of 25 recommendations discussing the diagnosis, pharmacological and non-pharmacological therapies, as well as monitoring for OA were formulated. Conclusion: These recommendations can be used to help clinicians in accurately diagnosing OA and choosing the most suitable therapy for their patients. All recommendation statements were tailored to the clinical setting, facility, and drug availability in Indonesia.

Indonesian Journal of Rheumatology

Journal Homepage: https://journalrheumatology.or.id/index.php/IJR

684

an important risk factor.4,6 Around 50% of patients aged 65 or older show radiographic signs of OA, yet only 10% of male and 13% of female elderlies show OA clinical symptoms, and approximately 10% of them suffer from OA-related disabilities.7

As life expectancy increases, demographic data from The USA Bureau of Census reported that the Indonesian elderly population has witnessed significant growth, with a staggering 283.3% increase between 1994 and 2020.8 The prevalence of radiographic OA in Indonesia is 15.5% in men and 12.7% in women aged 40-60 years old. Data from the rheumatology clinic at Hasan Sadikin Hospital in Bandung from 2007 to 2010 revealed that 73-74.48%

of rheumatology patients were diagnosed with OA, and 69% of them were female, with knee OA (87%) being the predominant type. These findings suggest that the number of OA patients will continue to rise, making OA a commonly encountered condition in daily clinical practice in the future. Therefore, it is necessary for physicians in Indonesia to have a better understanding of OA diagnosis and treatment.

OA therapy consists of pharmacological, non- pharmacological, and surgical interventions. However, this recommendation does not address surgical therapy in OA. The aims of pharmacological and non- pharmacological therapy are to reduce pain, maintain or improve joint movement function, reduce physical limitation, increase activity independence, and increase the patient’s quality of life.9 Current pharmacological therapy is also expected to modify disease progression or even prevent OA through the use of disease-modifying osteoarthritis drugs (DMOADs). Optimal outcomes in OA therapy can be achieved by using a multidisciplinary approach and utilizing multimodal therapy.1,10

2. Methods

The Indonesian Rheumatologist Association (IRA) formed a recommendation team to formulate recommendation questions for diagnosis, therapy, and monitoring of OA. There was also a team of supervisors (steering committee) consisting of 6 core members

from IRA. The panelist team consists of 51 rheumatologists from various branches of IRA and institutions in Indonesia, with at least five years of working experience as a rheumatologist. Each member of the panelist team gave an independent opinion regarding the level and strength of recommendations put forth by the recommendation team. No delegation from the pharmacy industry was involved in the process of developing these recommendations.

A total of 10 key questions were formulated to determine the recommendations for diagnosing and managing OA in Indonesia: 1) How can a patient be diagnosed with OA? 2) Is the classification or diagnosis criteria issued by ACR still used to diagnose OA? 3) What are the examinations required to diagnose OA?

4) How can comprehensive treatment be given to OA patients? 5) What are the non-pharmacological treatment choices available for OA patients? 6) What are the pharmacological treatment choices available for OA patients? 7) What educational information should be provided to OA patients? 8) What are the difficulties and comorbidities that should be considered in OA patients? 9) How can disease activity be monitored and therapy results assessed in OA patients? 10) What are the indications to refer OA patients?

Literature search was conducted through online databases, including PubMed, Science Direct, Google Scholar, and other databases, using these keywords:

osteoarthritis, diagnosis, NSAID, steroid, glucocorticoids, laboratory test, education, treatment, algorithm, DMOADs, monitoring, complication, and prognosis. The search was limited to published English meta-analysis, systematic review, clinical trial, randomized controlled trial (RCT), and observational study, published within 2011 to 2021.

Initial literature search yielded 439 relevant articles.

After a thorough reading, the team selected 114 articles to be included in the formulation of this recommendation.

The development of this diagnostic and management guideline is based on the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and

685

Evaluation (GRADE) approach, which requires adaptation of scientific evidence summaries from existing clinical practice guidelines, if available, or generating de novo summaries of scientific evidence if necessary. This process includes (1) identifying prioritized research questions through PICO (population-intervention-comparison-outcome) framework, (2) extracting, assessing, and synthesizing scientific evidence from existing clinical practice guidelines, meta-analyses, and systematic reviews of clinical trials or observational studies, (3) formulating summaries of scientific evidence, (4) voting on critical and important outcomes, (5) presenting scientific evidence to the panelist team, (6) formulating final recommendations, and (7) planning for dissemination, implementation, and updating.

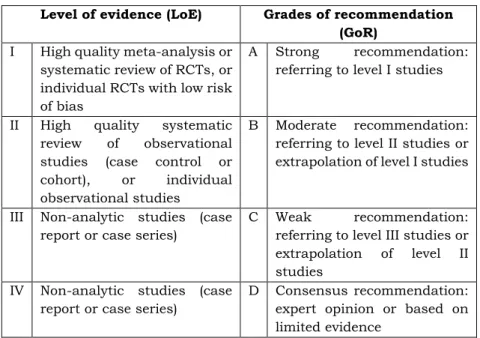

Recommendations were issued based on the 10 key questions above. The recommendation team then assigned the level of evidence (LoE) and grades of recommendation (GoR) based on the criteria listed in Table 1.11 These recommendations were then reviewed by the steering committee. In the final step, the

panelist team members were asked to rate each recommendation on a scale of 0 to 10 to determine the level of agreement (LoA). A score of 0 indicated complete disagreement and 10 indicated complete agreement. The panelist member would be asked for comments should a score below 8 was issued.

Recommendations with an average score below 8 were then rediscussed by the recommendation team to be revised and then reassessed by the panelist team to determine the final LoA.

Levels of evidence is a hierarchical system for classifying evidence based on the quality of the methodological design, validity, and its applicability to patient care. On the other hand, grades of recommendation are based on levels of evidence, considering the overall strength of evidence and the judgment of recommendation makers. Grades of recommendation are developed by considering cost, value, preferences, feasibility, risk-benefit assessment, along with the assessment of the quality of available scientific evidence.

Table 1. Level of evidence and grades of recommendations.

Level of evidence (LoE) Grades of recommendation (GoR)

I High quality meta-analysis or systematic review of RCTs, or individual RCTs with low risk of bias

A Strong recommendation:

referring to level I studies

II High quality systematic review of observational studies (case control or cohort), or individual observational studies

B Moderate recommendation:

referring to level II studies or extrapolation of level I studies

III Non-analytic studies (case report or case series)

C Weak recommendation:

referring to level III studies or extrapolation of level II studies

IV Non-analytic studies (case report or case series)

D Consensus recommendation:

expert opinion or based on limited evidence

3. Results

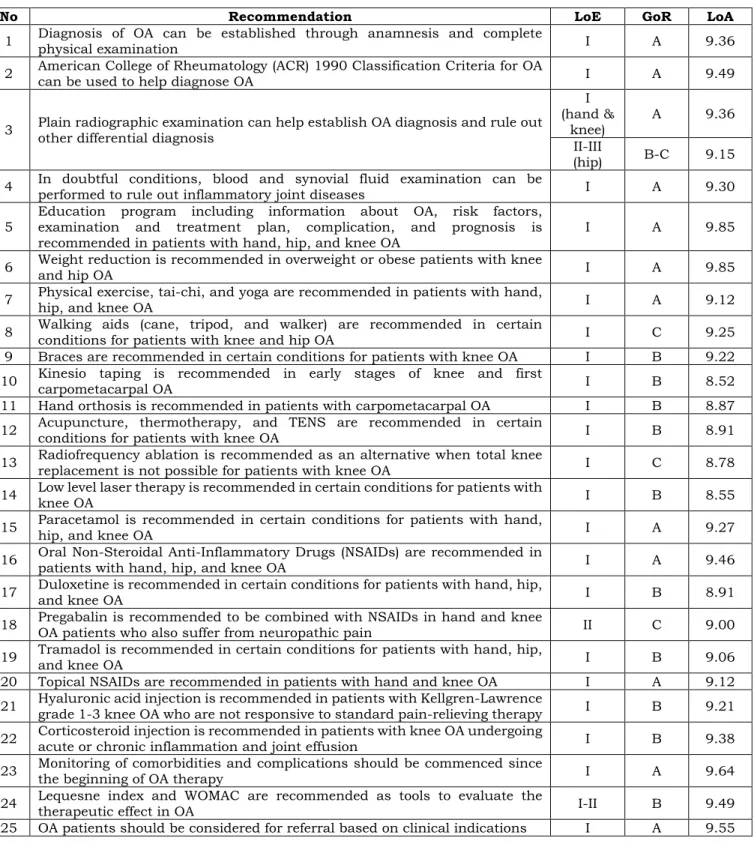

Based on the discussion, 25 recommendations were agreed upon by the recommendation team,

steering committee, and panelist team. Summary of these recommendations is provided in Table 2.

686

Table 2. Summary of recommendations for diagnosis and management of osteoarthritis.

No Recommendation LoE GoR LoA

1 Diagnosis of OA can be established through anamnesis and complete

physical examination I A 9.36

2 American College of Rheumatology (ACR) 1990 Classification Criteria for OA

can be used to help diagnose OA I A 9.49

3 Plain radiographic examination can help establish OA diagnosis and rule out other differential diagnosis

I (hand &

knee) A 9.36

II-III

(hip) B-C 9.15 4 In doubtful conditions, blood and synovial fluid examination can be

performed to rule out inflammatory joint diseases I A 9.30

5 Education program including information about OA, risk factors, examination and treatment plan, complication, and prognosis is

recommended in patients with hand, hip, and knee OA I A 9.85

6 Weight reduction is recommended in overweight or obese patients with knee

and hip OA I A 9.85

7 Physical exercise, tai-chi, and yoga are recommended in patients with hand,

hip, and knee OA I A 9.12

8 Walking aids (cane, tripod, and walker) are recommended in certain

conditions for patients with knee and hip OA I C 9.25

9 Braces are recommended in certain conditions for patients with knee OA I B 9.22 10 Kinesio taping is recommended in early stages of knee and first

carpometacarpal OA I B 8.52

11 Hand orthosis is recommended in patients with carpometacarpal OA I B 8.87 12 Acupuncture, thermotherapy, and TENS are recommended in certain

conditions for patients with knee OA I B 8.91

13 Radiofrequency ablation is recommended as an alternative when total knee

replacement is not possible for patients with knee OA I C 8.78

14 Low level laser therapy is recommended in certain conditions for patients with

knee OA I B 8.55

15 Paracetamol is recommended in certain conditions for patients with hand,

hip, and knee OA I A 9.27

16 Oral Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs) are recommended in

patients with hand, hip, and knee OA I A 9.46

17 Duloxetine is recommended in certain conditions for patients with hand, hip,

and knee OA I B 8.91

18 Pregabalin is recommended to be combined with NSAIDs in hand and knee

OA patients who also suffer from neuropathic pain II C 9.00

19 Tramadol is recommended in certain conditions for patients with hand, hip,

and knee OA I B 9.06

20 Topical NSAIDs are recommended in patients with hand and knee OA I A 9.12 21 Hyaluronic acid injection is recommended in patients with Kellgren-Lawrence

grade 1-3 knee OA who are not responsive to standard pain-relieving therapy I B 9.21 22 Corticosteroid injection is recommended in patients with knee OA undergoing

acute or chronic inflammation and joint effusion I B 9.38

23 Monitoring of comorbidities and complications should be commenced since

the beginning of OA therapy I A 9.64

24 Lequesne index and WOMAC are recommended as tools to evaluate the

therapeutic effect in OA I-II B 9.49

25 OA patients should be considered for referral based on clinical indications I A 9.55

4. Discussion

Recommendation 1: Diagnosis of OA can be established through anamnesis and complete physical examination

The most common symptom of OA is joint pain which worsens with activity and improves with rest

(gelling phenomenon).12 Patients may also suffer from morning stiffness or stiffness after resting. The joint may also become swollen. Crepitation and limited range of motion may be observed upon joint movement. Inflammation is usually absent or minimal. OA can affect multiple joints, mainly the

687

knee, feet, hands, vertebrae, and hip joints.1

Physical examination can be conducted using the gait, arms, legs, spine (GALS) principle.13 The diagnosis of OA can be established clinically; no specific supporting examination is required.

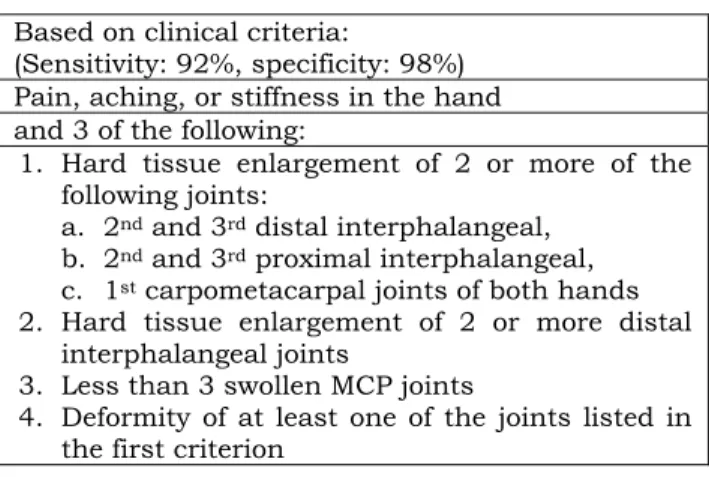

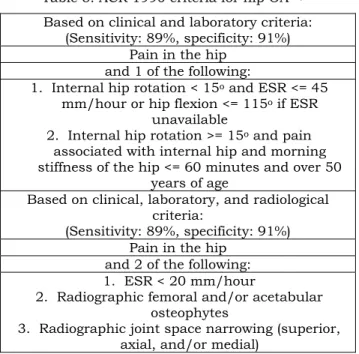

Recommendation 2: American College of Rheumatology (ACR) 1990 classification criteria

for OA can be used to help diagnose OA

Several diagnostic criteria were developed to assist physician in diagnosing OA, including ACR 1990, EULAR, and NICE criteria.14 We recommend using the ACR 1990 criteria as they have high sensitivity and specificity and have been clinically tested. The ACR 1990 criteria for hand, hip, and knee OA are provided in Table 3-5.1,15–18

Table 3. ACR 1990 criteria for hand OA16,17 Based on clinical criteria:

(Sensitivity: 92%, specificity: 98%) Pain, aching, or stiffness in the hand and 3 of the following:

1. Hard tissue enlargement of 2 or more of the following joints:

a. 2nd and 3rd distal interphalangeal, b. 2nd and 3rd proximal interphalangeal, c. 1st carpometacarpal joints of both hands 2. Hard tissue enlargement of 2 or more distal

interphalangeal joints

3. Less than 3 swollen MCP joints

4. Deformity of at least one of the joints listed in the first criterion

Table 4. ACR 1990 criteria for knee OA19,20 Based on clinical criteria:

(Sensitivity 95%, specificity 69%) Pain in the knee

and 3 of the following:

1. Over 50 years of age

2. Less than 30 minutes of morning stiffness 3. Crepitus on active motion

4. Bony tenderness 5. Bony enlargement 6. No palpable warmth of synovium Based on clinical and laboratory criteria:

(Sensitivity: 92%, specificity: 75%) 1. Over 50 years of age

2. Less than 30 minutes of morning stiffness 3. Crepitus on active motion

4. Bony tenderness 5. Bony enlargement 6. No palpable warmth of synovium

7. ESR<40 mm/hour 8. Rheumatoid factor (RF) < 1:40 9. Synovial fluid shows signs of OA Based on clinical and radiological criteria:

(Sensitivity: 91%, specificity: 86%) Pain in the knee

and osteophytes and one of the following:

1. Over 50 years of age

2. Less than 30 minutes of morning stiffness 3. Crepitus on active motion

688

Table 5. ACR 1990 criteria for hip OA21,22 Based on clinical and laboratory criteria:

(Sensitivity: 89%, specificity: 91%) Pain in the hip

and 1 of the following:

1. Internal hip rotation < 15o and ESR <= 45 mm/hour or hip flexion <= 115o if ESR

unavailable

2. Internal hip rotation >= 15o and pain associated with internal hip and morning stiffness of the hip <= 60 minutes and over 50

years of age

Based on clinical, laboratory, and radiological criteria:

(Sensitivity: 89%, specificity: 91%) Pain in the hip

and 2 of the following:

1. ESR < 20 mm/hour

2. Radiographic femoral and/or acetabular osteophytes

3. Radiographic joint space narrowing (superior, axial, and/or medial)

Recommendation 3: Plain radiographic examination can help establish OA diagnosis and rule out other differential diagnosis

Plain radiographic examination may show structural changes in the joint of OA patients.

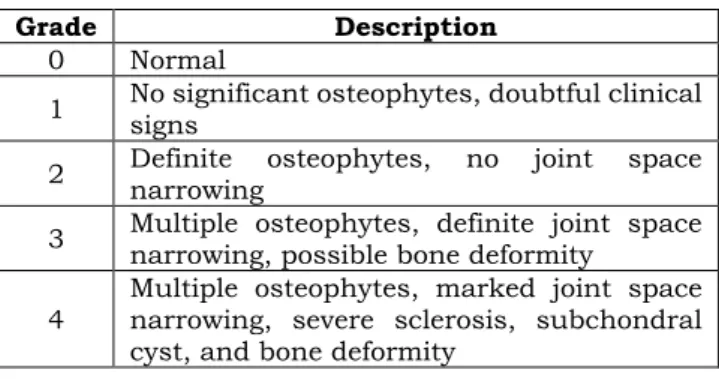

Findings include joint space narrowing, osteophytes, subchondral sclerosis, subchondral cyst, and joint effusion.23 Kellgren-Lawrence classification can be used to determine knee OA severity, ranging from grade 0 to 4 (see Table 6). Plain knee radiographic examination is done in anteroposterior projection while the patient is standing, with the knee flexed at a 20o angle and the feet externally rotated at 15o.24

Several meta-analyses have demonstrated that plain radiography is highly reliable in assessing knee and hand OA severity based on joint space narrowing.25–27 However, the benefit of radiographic examination in hip OA is still controversial, as the radiographic findings often do not align with the patient’s clinical manifestation.27,28 Alternative imaging modalities such as ultrasonography (USG) and 1.5 T magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may also be employed.29–31 However, these modalities are rarely indicated in OA patients, except for evaluating patients undergoing stem cell therapy.32

Table 6. Kellgren-Lawrence classification24

Grade Description

0 Normal

1 No significant osteophytes, doubtful clinical signs

2 Definite osteophytes, no joint space narrowing

3 Multiple osteophytes, definite joint space narrowing, possible bone deformity

4 Multiple osteophytes, marked joint space narrowing, severe sclerosis, subchondral cyst, and bone deformity

689

Recommendation 4: In doubtful conditions, blood and synovial fluid examination can be performed to rule out inflammatory joint diseases

Blood examinations are not routinely performed in diagnosing OA patients. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP) can be measured to rule out other inflammatory arthritis.

Rheumatoid factor (RF) and anti-citrullinated protein antibody (ACPA) can also be measured to rule out rheumatoid arthritis (RA).33 Serum uric acid levels can be measured to rule out gout arthritis. Synovial fluid analysis can be performed if there is joint effusion, to rule out gout or other crystal arthropathies.34,35

Recommendation 5: Education program including information about OA, risk factors, examination and treatment plan, complication, and prognosis is recommended in patients with hand, hip, and knee OA

Education regarding patient’s disease condition, treatment plan, complication, and prognosis is very important. It can be done on an individual basis or in a group-based session, either in-person or through online session using any media. A meta-analysis following up OA patients for 6 months showed that effective education had significant effect in reducing pain and improving physical function compared to patients who did not receive education.36

Recommendation 6: Weight reduction is recommended in overweight or obese patients with knee and hip OA

Excessive body weight has been shown to accelerate the progression of cartilage destruction.

Three meta-analyses have shown that weight reduction is effective in reducing pain level and improving joint function in patients with knee or hip OA. For every 1% decrease in body weight, there was a corresponding 2% decrease in WOMAC (The Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index) score. To achieve optimal results, these studies recommend weight reduction of up to 25% of the initial body weight. Physical activities such as static cycling,

walking, and water sports can be done to help reduce body weight. These physical activities modify the body composition by reducing body fat mass to achieve proportional body weight and may also strengthen muscles and increase joint stability.37–39

Recommendation 7: Physical exercise, tai-chi, and yoga are recommended in patients with hand, hip, and knee OA

Suitable physical exercise has been proven to be beneficial to joint health through chondroprotective mechanism.40 Physical exercise can be done in OA patients with mild to moderate pain. For those experiencing severe and acute pain, it is recommended to follow the PRICE protocol (Protection, Rest, Ice, Compression, and Elevation). Three meta-analyses have shown that physical exercise may reduce pain and improve joint function in patients with hand, hip, and knee OA. Land-based exercises are recommended for patients with hip and knee OA, while isometric exercises (such as gripping) for 3-6 months is effective for patients with hand OA. The recommended exercise duration is at least 60 minutes a week. Static cycling is the most beneficial type of exercise for knee OA.

Quadriceps and lower leg muscle strengthening exercises are also proven to relieve pain in knee OA.

Aquatic exercise can be an alternative for patients unable to perform land-based exercise. The recommended physical exercises are non-weight bearing exercises, including swimming, static cycling, and aerobic exercises.40–42

Tai-chi is a traditional Chinese exercise which combines meditation with breathing exercises and relaxation. Several studies have shown that tai-chi significantly reduce pain levels, and improve physical function in OA patients during 6 months of follow-up.

It is recommended to practice tai chi 2-3 times a week, with 60 minutes duration.43–45

Another form of exercise that combines meditation with physical exercise, relaxation, and breathing is yoga, which originates from India. Studies have shown that yoga is proven to be effective in relieving pain and stiffness while also improving joint and physical

690

function. The recommended regimen is 60 minutes duration for twice a week.43,46,47

Recommendation 8: Walking aids (cane, tripod, and walker) are recommended in certain conditions for patients with knee and hip OA

Walking aids are recommended for OA patients who are at high risk of falling, especially those with hip and knee OA. Walking aids may help these patients to increase joint stability, decrease pain, and halt the progression of cartilage destruction. Several RCTs (randomized controlled trials) have shown that walking aids were effective in decreasing pain, especially in OA patients with mild or moderate pain who can still walk.48,49

Cane is recommended for knee and hip OA patients without stability impairment, with the recommended type being the T cane, used in the contralateral side of the affected hip or knee joint. Tripods, quadripods, or walkers are recommended for knee and hip OA patients with stability impairment.50

Recommendation 9: Braces are recommended in certain conditions for patients with knee OA

Knee braces can be used as a part of occupational therapy to protect the joint. These braces include tibiofemoral and patellofemoral braces. Tibiofemoral brace can be used in patients with knee joint instability caused by quadriceps muscle weakness without patellar instability. Whereas patellofemoral brace can be used in patients suffering patellar instability.51,52 Several meta-analyses have shown that braces were effective in relieving pain and improving physical function.52,53 However, braces are contraindicated in patients with severe venous insufficiency or deep vein thrombosis. The recommended duration of brace usage is 6 hours a day, 5 days a week, for at least 6 weeks, and should be combined with muscle strengthening exercises to prevent muscle atrophy.53

Recommendation 10: Kinesio taping is recommended in early stages of knee and first carpometacarpal OA

In contrast to braces, kinesio taping still allows for joint movement, unlike braces which maintain joint position.54 Three meta-analyses have demonstrated that kinesio taping (with facilitation technique) effectively reduces pain, improves physical function, and increases flexibility and muscle strength.54–56 Optimal results are typically achieved after 6 weeks of usage. Kinesio taping is indicated in the early stages of OA, provided that they do not have allergies, acute infections, acute inflammation, or deep vein thrombosis.57

Recommendation 11: Hand orthosis is recommended in patients with carpometacarpal OA

Several meta-analyses have shown that

immobilizing carpometacarpal and

metacarpophalangeal joints is effective in reducing pain, improving function, and enhancing hand strength in patients with hand OA.58–60 Long thermoplastic orthosis is the recommended choice for reducing pain, while short thermoplastic orthosis is the recommended choice for improving function.58,60 These effects can be observed after 2 weeks of hand orthosis usage.61

Recommendation 12: Acupuncture, thermotherapy, and TENS are recommended in certain conditions for patients with knee OA

Thermotherapy is a form of therapy which utilizes temperature intervention, consisting of heat and cold modalities. Each modality is used depending on the patient’s condition. Heat thermotherapy was shown to be beneficial in reducing pain if used together with isokinetic exercise but did not give significant result in improving physical function. Thermotherapy can be considered as an additional therapy for obese patients with knee OA, combined with physical exercise. The recommended heat thermotherapy is pulse short-wave therapy. 62,63

691

The other form of thermotherapy is cold thermotherapy, also known as cryotherapy, which uses cryogens to freeze tissue under the skin or mucosa. Limited evidence is available regarding the use of cryotherapy for OA treatment, therefore currently, cryotherapy is not included as a form of non-pharmacological therapy in OA. 64

Acupuncture is a traditional therapy from China which uses fine needles punctured in certain areas in the body. Two meta-analyses have demonstrated that acupuncture is effective in reducing pain and improving physical function. However, due to the lack of standardization in the methods used in acupuncture therapy, it is considered as an adjuvant therapy when classic analgesics do not give sufficient results.65,66

Trans Electrical Nerve Stimulation (TENS) is a non- invasive peripheral stimulation method which utilizes low voltage electricity to reduce pain. Several meta- analyses have shown that TENS is effective in reducing pain, although it has not yielded significant result in physical function improvement.67–69 Moreover, the TENS procedure performed varies across studies in terms of the number of sessions and duration. Thus, TENS can be considered as an alternative or adjuvant therapy to reduce chronic pain.

Recommendation 13: Radiofrequency ablation is recommended as an alternative when total knee replacement is not possible for patients with knee OA

Knee radiofrequency ablation is a procedure that utilizes heat or cold modalities to disrupt pain signaling in the genicular nerve. This therapy is often used in patients suffering from chronic pain. Two meta-analyses have shown that radiofrequency ablation is effective in reducing pain and improving physical function.70,71 It can also be used for long-term therapy without significant side effects, and it has the potential to reduce the need for analgesics in knee OA patients. Currently, radiofrequency ablation is only recommended for grade IV knee OA patients, since there is still no standardization in its utilization.70

Recommendation 14: Low level laser therapy is recommended in certain conditions for patients with knee OA

Low level laser therapy (LLLT) uses light-emitting diodes to emit low-level laser onto body surface, inducing changes in the cell biological activities to reduce inflammation and pain. One meta-analysis has shown a significant effect of LLLT in reducing pain after 12 weeks of usage. However, another meta- analysis reported no significant effect of LLLT in OA patients, probably due to high heterogeneity between studies. In both studies, LLLT was used in grade II-IV knee OA patients experiencing persistent pain after 6 months. LLT is contraindicated in malignancy, pregnancy, and photosensitive patients. 72–74

Recommendation 15: Paracetamol is recommended in certain conditions for patients with hand, hip, and knee OA

Paracetamol or acetaminophen is the chosen analgesic for long-term use, especially in the elderly, due to its good safety profile compared to NSAIDs.5,75–

77 Several meta-analyses have shown that paracetamol provides minimal improvement in relieving pain, without increasing the risk of side effects in OA patients.78–80 The recommended dose is 1000 mg per administration, with a maximum dose of 4000 mg per day. Several guidelines also consistently recommend paracetamol as the first-line analgesic for OA patients.

Monitoring of hepatotoxic effect is required in patients receiving 3-4 grams of paracetamol a day. Paracetamol is recommended for mild to moderate pain in grade I- III OA patients. It can also be considered in OA patients who are contraindicated to oral NSAIDs, or elderly who need long-term analgesics.78

Recommendation 16: Oral Non-Steroidal Anti- Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs) are recommended in patients with hand, hip, and knee OA

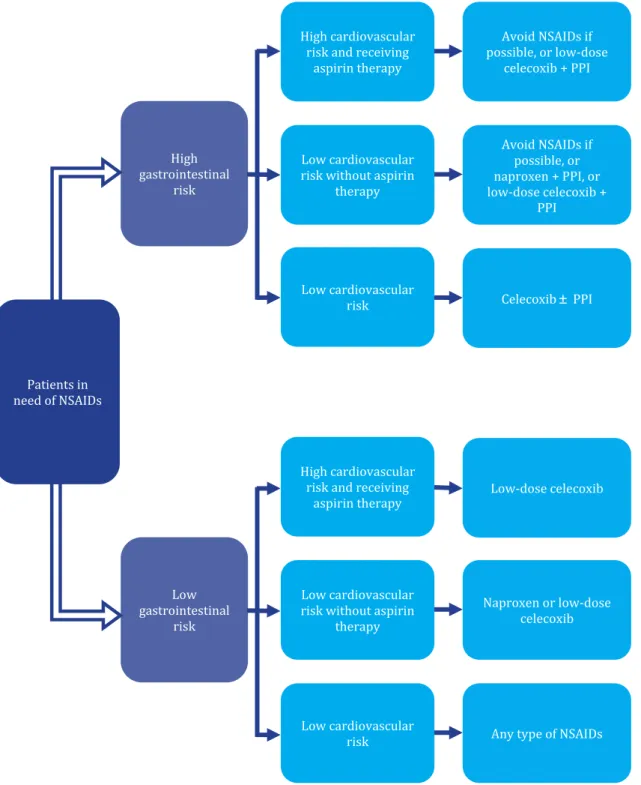

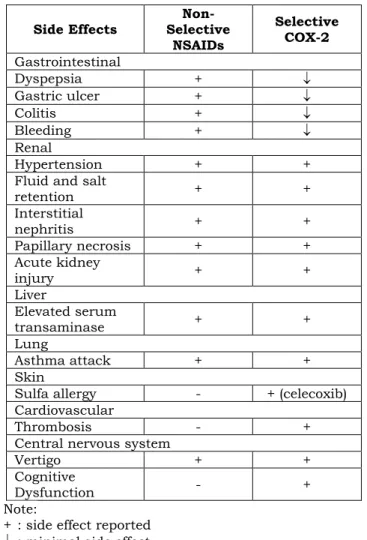

NSAIDs have anti-inflammatory and analgetic effects with good efficacy. They should be given in the lowest dose that still gives therapeutic effect. Several clinical conditions should be considered when

692

prescribing NSAIDs due to potential gastrointestinal, cardiovascular, and renal side effects.1 A meta- analysis have shown that NSAIDs have a significant effect in relieving pain compared to placebo or paracetamol in OA patients.79 The recommendation

regarding the selection of NSAIDs based on the patient’s risk factors is provided in Table 7 and Figure 1, whereas the side effects of NSAIDs can be seen in Table 8.

Table 7. Risk factors to be considered when choosing NSAIDs based on patient’s risk factors81 Cardiovascular risk

1. Every patient who uses long-term NSAIDs should undergo cardiovascular examination at least once a year.

2. NSAIDs usage is related to an increased risk of having acute coronary syndrome or other cardiovascular atherothrombotic events (stroke and other peripheral artery problems). The increased cardiovascular risk also depends on the type of NSAIDs used. Naproxen is considered one of the safest choices, while rofecoxib, diclofenac, etodolac, and indomethacin are associated with a higher cardiovascular risk.

3. Combination of anticoagulant (warfarin, coumarin derivatives, etc.) and NSAIDs should be avoided. If truly necessary, coxibs have the lowest risk.

4. The use of NSAIDs must be avoided in patients with acute myocardial infarction, even for a short term, as it can increase cardiovascular risk. Ibuprofen and naproxen can disrupt the antiplatelet effect of low-dose aspirin. In patients who are taking low-dose aspirin to prevent cardiovascular events, coxibs can be considered as the safest long-term NSAIDs choice.

Gastrointestinal risk

1. Gastrointestinal risk must be assessed in all patients taking NSAIDs. Patients older than 60 years old or with history of gastrointestinal ulcers have increased risk of having gastrointestinal complications.

2. It is not advisable to combine two or more NSAIDs at the same time.

3. Usage of H2 antagonist to prevent gastrointestinal complication is not recommended. The use of proton pump inhibitor (PPI) together with non-selective NSAIDs is the correct strategy to prevent gastrointestinal complication. Coxibs are more preferrable compared to combination of non-selective NSAIDs and PPI.

4. NSAIDs are not recommended in patients with liver cirrhosis and/or inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). If truly necessary, coxibs can be chosen at the lowest effective dose and for the shortest possible duration.

Renal risk

1. Renal function test must be conducted at least once a year in patients who use long-term NSAIDs.

2. NSAIDs should not be used in patients with stage 3 chronic kidney disease (CKD) with/without cardiovascular problems, except in special situations, the usage of NSAIDs must be tightly evaluated. NSAIDs are contraindicated in patients with stage 4 and 5 CKD.

Other clinical conditions

1. Anemia or decrease of 2 g/dl of hemoglobin concentration is common in patients who consume NSAIDs. Coxibs have lower risk of inducing anemia.

2. Combination of paracetamol and NSAIDs is recommended for short-term analgesics in post-operative patients.

693

Information:

• Low-dose celecoxib = 200 mg once daily

• Patients with history of peptic ulcer should be investigated for Helicobacter pylori infection

Figure 1. Algorithm in choosing NSAIDs in patients with gastrointestinal and cardiovascular risk82 Patients in

need of NSAIDs

Low gastrointestinal

risk High gastrointestinal

risk

High cardiovascular risk and receiving

aspirin therapy

Low cardiovascular risk without aspirin

therapy

Low cardiovascular risk

Avoid NSAIDs if possible, or low-dose

celecoxib + PPI

High cardiovascular risk and receiving

aspirin therapy

Low cardiovascular risk without aspirin

therapy

Low cardiovascular risk

Avoid NSAIDs if possible, or naproxen + PPI, or low-dose celecoxib +

PPI

Celecoxib PPI

Low-dose celecoxib

Naproxen or low-dose celecoxib

Any type of NSAIDs

694

Table 8. Side Effects of non-selective NSAIDs and selective COX-2.

Side Effects Non- Selective

NSAIDs

Selective COX-2 Gastrointestinal

Dyspepsia +

Gastric ulcer +

Colitis +

Bleeding +

Renal

Hypertension + +

Fluid and salt

retention + +

Interstitial

nephritis + +

Papillary necrosis + +

Acute kidney

injury + +

Liver

Elevated serum

transaminase + +

Lung

Asthma attack + +

Skin

Sulfa allergy - + (celecoxib)

Cardiovascular

Thrombosis - +

Central nervous system

Vertigo + +

Cognitive

Dysfunction - +

Note:

+ : side effect reported

: minimal side effect - : no side effect reported

Recommendation 17: Duloxetine is recommended in certain conditions for patients with hand, hip, and knee OA

Duloxetine is a serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) antidepressant drug, which works by inhibiting the reuptake process of serotonin and norepinephrine in the central nervous system. It is also used as an analgesic.84

Three meta-analyses have shown that duloxetine is effective in relieving pain and improving joint function of OA patients. Duloxetine is also proven to be effective in improving mood and patient’s quality of life with minimal side effect.84–86 Duloxetine can be used in OA patients if other analgesics give inadequate effect. The starting dose for duloxetine is 30-40 mg/day for 1-2 weeks, which can be increased to 60 mg/day and combined with NSAIDs or paracetamol.85 Duloxetine

can be used in OA patients with chronic pain, but it should be used with caution, since it can increase suicide risk, and also bleeding risk when used in combination with warfarin, NSAIDs, or aspirin.85

Recommendation 18: Pregabalin is recommended to be combined with NSAIDs in hand and knee OA patients who also suffer from neuropathic pain

Pregabalin (gabapentin) is a derivative form of gamma-aminobutyric acid, which is a neurotransmitter that inhibits the calcium ion channel. It is usually used to treat epilepsy and neuropathic pain. Pregabalin is thought to relieve pain in OA patients through inhibition of pain sensitization.

Three RCTs have demonstrated that pregabalin significantly reduces pain and improves joint function in patients with hand and knee OA.87–89 The

695

effectiveness increases when used in combination with NSAIDs.88,89 The therapeutic dose is 150 mg/day for 3 months. The contraindication for pregabalin includes history of depression, concomitant use of antidepressant, glomerular filtration rate <60 ml/min, liver impairment (increase of ALT >2.5 times of upper normal limit), and alcoholism.87

Recommendation 19: Tramadol is recommended in certain conditions for patients with hand, hip, and knee OA

Tramadol is an opioid agonist which is used as an analgesic for treating moderate to severe pain with a rapid onset.90 A meta-analysis study has shown that tramadol significantly decreases pain.91 However, another meta-analysis reported that compared to placebo, tramadol alone or in combination with acetaminophen did not give significant pain relief or joint function improvement in OA patients.90 The recommended dose for tramadol ranges between 37.5 and 400 mg per day.90 Tramadol can be considered in patients who are contraindicated to NSAIDs, unresponsive to other analgesics, or in patients who are ineligible for surgery.1 The possible side effects include nausea, vomiting, dizziness, constipation, fatigue, headache, addiction, and respiratory depression.1,90

Recommendation 20: Topical NSAIDs are recommended in patients with hand and knee OA

Topical NSAIDs relieve pain by locally inhibiting inflammatory mediators. They are available in the form of gel, cream, or patch. Topical NSAIDs are mainly used for patients who are contraindicated to systemic therapy.

Patch is proven to be effective in relieving pain, with the advantages of having adhesive agent, retaining layer, and a membrane which controls the releasing rate of active agents. The active agents enter through subcutaneous tissue to intraarticular tissue with higher concentration compared to plasma. The concentration of the active agents also drops faster when the patch is removed, which makes patch safer

and easier to control compared to systemic NSAIDs.

Most used patches include diclofenac and proven group.92,93

Meta-analysis studies have shown that topical NSAIDs are beneficial in decreasing pain in OA patients, with lower gastrointestinal toxicity and no serious side effects.94–96 Diclofenac patch was shown to be the most effective topical NSAIDs in relieving pain.96 Another study also showed that ketoprofen patch has similar effectiveness to diclofenac patch.93

Recommendation 21: Hyaluronic acid injection is recommended in patients with Kellgren-Lawrence grade 1-3 knee OA who are not responsive to standard pain-relieving therapy

Intraarticular or periarticular injection is not the main choice in treating OA, and its usage should also be done with caution and selectivity, considering the local and systemic side effects that may arise. The procedure should also be done by rheumatologists, internists, or other competent specialists.

Intraarticular injection can be considered in Kellgren- Lawrence grade 1-3 patients, in whom standard therapy fails.97 The contraindications for intraarticular injection include joint infection, skin infection in the site of injection, thrombocytopenia, coagulopathy, and allergy to the injected agent.98

Hyaluronic acid has anti-inflammatory, mechanic, analgetic effects, and positive affects proteoglycan and glycosaminoglycan synthesis. There are two types of hyaluronic acid available in Indonesia, which are high molecular weight and low molecular weight, and the mixed type. A study has shown that intraarticular hyaluronic acid has chondroprotective, anti- inflammatory, analgetic, joint lubricant, and shock- absorbing effects.99 The recommended dose is 20 mg a week for 5 weeks, 30 mg a week for 3 weeks, or 60 mg single dose.97

Hyaluronic acid injection is recommended in Kellgren-Lawrence grade 1-3 patients, who are unresponsive to standard therapy and/or contraindicated to other therapy. Meta-analysis studies have shown that corticosteroid injection is

696

more effective compared to hyaluronic acid in relieving pain in the short-term (up to one month), but hyaluronic acid is more effective for long-term pain- relief (up to 6 months).97,100,101

Recommendation 22: Corticosteroid injection is recommended in patients with knee OA undergoing acute or chronic inflammation and joint effusion

Corticosteroid intraarticular injection can relieve pain in knee OA by inhibiting inflammation and decreasing prostaglandin synthesis.102 Corticosteroid injection is recommended in OA patients with acute or chronic inflammation and joint effusion.103 Three meta-analyses have shown that corticosteroid injection is more effective compared to hyaluronic acid in relieving pain for short-term duration (up to one month).97,100,101

Recommendation 23: Monitoring of comorbidities and complications should be commenced since the beginning of OA therapy

Comprehensive assessment regarding OA patient’s quality of life should be done in the beginning of therapy. The decision to treat OA should be individualized and take into account other medical conditions such as hypertension, cardiovascular disease, gastrointestinal bleeding risk, renal disease, etc. Liver and renal function should be monitored to minimize risk of drug side effects. Hepatotoxic drugs such as paracetamol must be avoided in patients with impaired liver function, while drugs that are eliminated by urine excretion must be avoided in patients with impaired kidney function. Local therapy, if possible, is more recommended than systemic therapy to minimize risk of side effects. NSAIDs should be used for the shortest duration at the lowest therapeutic dose.107,108

Gastrointestinal problems that may arise during OA therapy include heartburn sensation, abdominal discomfort, peptic ulcer, hematemesis, and melena.

Risk factors that may increase gastrointestinal side effects include history of peptic ulcer, dyspepsia, GI bleeding, previous intolerance to NSAIDs, steroids use,

anticoagulant, comorbidities, use of more than one NSAIDs, smoking, and alcoholism.82

Regarding cardiovascular and renal safety, several problems need to be considered, including hypertension, congestive heart failure, kidney failure, and hyperkalemia. Long-term use of NSAIDs may cause a decrease in glomerular filtration rate.109,110

Recommendation 24: Lequesne index and WOMAC are recommended as tools to evaluate the therapeutic effect in OA

Lequesne index is used to objectively assess the severity of knee and hip OA based on clinical aspects.

This severity categorization can help guide treatment modality selection in OA patients.111

WOMAC index can also be used to assess functional impairment and pain in OA patients. It is a valid and reliable index which assess 17 functional activities, 5 painful activities, and 2 stiffness problems.112,113

Recommendation 25: OA patients should be considered for referral based on clinical indications OA patients should be referred to internists or rheumatologists for further examination and appropriate therapy.114 The indications for referral include: 1) Patients with doubtful diagnosis or suspicion of other joint diseases. 2) Patients with comorbidities and multiple pathologies. 3) Patients who fail to respond to standard therapy. 4) Patients who need non-surgical intervention.

Surgical therapy should be considered in OA patients with these conditions: 1) OA patients with severe joint symptoms (pain, stiffness, functional impairment) that severely impact patients’ quality of life. 2) Patients with refractory joint symptoms despite adequate non- surgical therapy. 3) Patients with severe pain can be considered to be referred for surgical therapy before prolonged functional limitation occurs. If joint damage/deformity meets the indication as stated in number 1, then it falls under the indication for surgery.

697

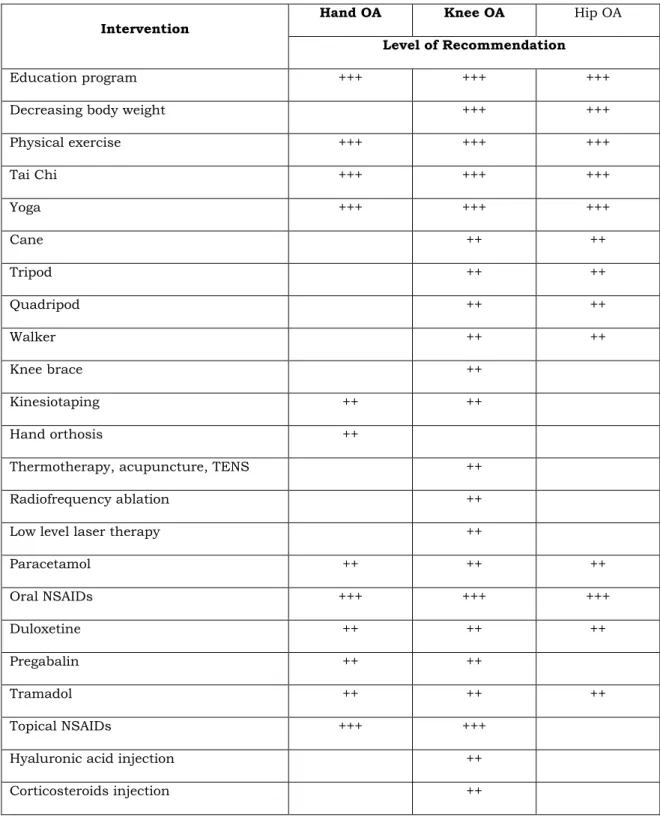

Table 9. Summary of therapy recommendation in osteoarthritis.

Intervention Hand OA Knee OA Hip OA

Level of Recommendation

Education program +++ +++ +++

Decreasing body weight +++ +++

Physical exercise +++ +++ +++

Tai Chi +++ +++ +++

Yoga +++ +++ +++

Cane ++ ++

Tripod ++ ++

Quadripod ++ ++

Walker ++ ++

Knee brace ++

Kinesiotaping ++ ++

Hand orthosis ++

Thermotherapy, acupuncture, TENS ++

Radiofrequency ablation ++

Low level laser therapy ++

Paracetamol ++ ++ ++

Oral NSAIDs +++ +++ +++

Duloxetine ++ ++ ++

Pregabalin ++ ++

Tramadol ++ ++ ++

Topical NSAIDs +++ +++

Hyaluronic acid injection ++

Corticosteroids injection ++

Note:

Recommended (+++) when supported by high-quality scientific evidence which indicates that the benefits outweigh the harms in the target population.

Recommended in specific conditions (++) when supported by scientific evidence of good quality in specific conditions and related to cost, equity, and implementation issues.

Considered in specific conditions (+) when the existing scientific evidence is not strong enough or when there are differences in outcomes and related to cost, equity, and implementation issues.

698

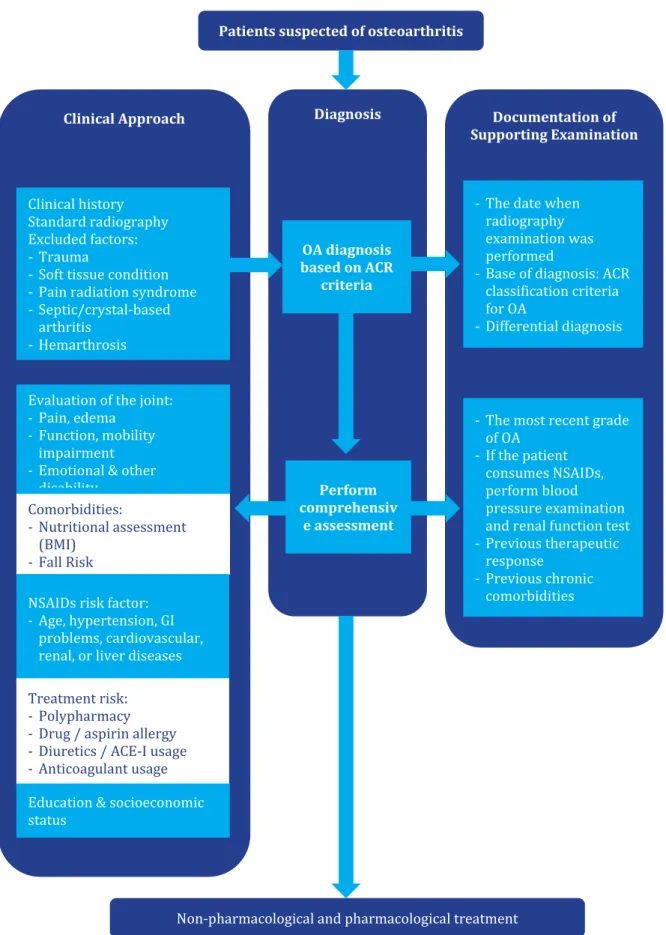

Figure 2. Diagnostic approach diagram in osteoarthritis.

Patients suspected of osteoarthritis

Diagnosis

Clinical Approach Documentation of

Supporting Examination

Evaluation of the joint:

- Pain, edema - Function, mobility

impairment - Emotional & other

disability

Comorbidities:- Nutritional assessment (BMI)

- Fall Risk

NSAIDs risk factor:

- Age, hypertension, GI problems, cardiovascular, renal, or liver diseases

Treatment risk:- Polypharmacy - Drug / aspirin allergy - Diuretics / ACE-I usage - Anticoagulant usage

Education & socioeconomic status

Perform comprehensiv

e assessment OA diagnosis based on ACR

criteria

- The date when radiography examination was performed

- Base of diagnosis: ACR classification criteria for OA

- Differential diagnosis

- The most recent grade of OA

- If the patient consumes NSAIDs, perform blood pressure examination and renal function test - Previous therapeutic

response - Previous chronic

comorbidities

Non-pharmacological and pharmacological treatment Clinical history

Standard radiography Excluded factors:

Trauma

Soft tissue condition Pain radiation syndrome Septic/crystal-based arthritis

Hemarthrosis

699

5. Conclusion

These recommendations aim to provide guidance on the diagnosis and management of osteoarthritis in Indonesia. The diagnostic, therapy, and monitoring algorithms in this recommendation are all tailored to suit Indonesia’s clinical setting, facility, and drug availability. A summary of the diagnostic approach in OA is presented in Figure 2. We hope that this recommendation can serve as a guideline for physicians in Indonesia when managing OA patients.

6. References

1. Kolasinski SL, Neogi T, Hochberg MC, Oatis C, Guyatt G, Block J, et al. 2019 American College of rheumatology/arthritis foundation guideline for the management of osteoarthritis of the hand, hip, and knee. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2020; 72(2): 149–62.

2. Murray CJL, Vos T, Lozano R, Naghavi M, Flaxman AD, Michaud C, et al. Disability- adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990-2010: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. The Lancet. 2012; 380(9859): 2197–223.

3. Bannuru RR, Osani MC, Vaysbrot EE, Arden NK, Bennell K, Bierma-Zeinstra SMA, et al.

OARSI guidelines for the non-surgical management of knee, hip, and polyarticular osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2019;

27(11): 1578–89.

4. Palazzo C, Nguyen C, Lefevre-Colau MM, Rannou F, Poiraudeau S. Risk factors and burden of osteoarthritis. Ann Phys Rehabil Med.

2016; 59(3): 134–8.

5. Rillo O, Riera H, Acosta C, Liendo V, Bolaños J, Monterola L, et al. PANLAR consensus recommendations for the management in osteoarthritis of hand, hip, and knee. Journal of Clinical Rheumatology. 2016;22(7):345–54.

6. Anderson AS, Loeser RF. Why is OA an age- related disease. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol.

2010; 24(1): 1–18.

7. Kwoh CK. Epidemiology of osteoarthritis. The

Epidemiology of Aging. 2012; 26(3): 523–36.

8. BAPPENAS. Indonesian population projection 2000-2025. Jakarta: Pusat Penelitian dan Pengembangan Kementerian Kesehatan Republik Indonesia; 2005.

9. Grässel S, Muschter D. Recent advances in the treatment of osteoarthritis [ version 1; peer review: 3 approved]. F1000Res. 2020; 9(325): 1–

17.

10. Karsdal MA, Michaelis M, Ladel C, Siebuhr AS, Bihlet AR, Andersen JR, et al. Disease- modifying treatments for osteoarthritis (DMOADs) of the knee and hip: lessons learned from failures and opportunities for the future.

Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2016; 24(12): 2013–21.

11. Hancock JL. A new system for grading recommendations in evidence based guidelines.

Br Med J. 2001; 323(3): 334–6.

12. Sinusas K. Osteoarthritis:Diagnosis and treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2012; 85(1): 49–

56.

13. Beattie KA, Bobba R, Bayoumi I, Chan D, Schabort I, Boulos P, et al. Validation of the GALS musculoskeletal screening exam for use in primary care: A pilot study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2008; 9(5): 115–22.

14. Skou ST, Koes BW, Grønne DT, Young J, Roos EM. Comparison of three sets of clinical classification criteria for knee osteoarthritis: a cross-sectional study of 13,459 patients treated in primary care. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2020;

28(2): 167–72.

15. Martel-Pelletier J, Maheu E, Pelletier JP, Alekseeva L, Mkinsi O, Branco J, et al. A new decision tree for diagnosis of osteoarthritis in primary care: international consensus of experts. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2019; 31(1): 19–30.

16. Haugen IK, Felson DT, Abhishek A, Berenbaum F, Bierma-Zeinstra S, Borgen T, et al.

Development of classification criteria for hand osteoarthritis: Comparative analyses of persons with and without hand osteoarthritis. RMD Open. 2020; 6(2): 1–8.

700

17. Brown C, Cooke TD, Daniel W, Greenwald RGR, Hochberg M, Howell D, et al. Arthritis &

rheumatism the American College of rheumatology reporting of osteoarthritis of the hand. Arthritis Rheum. 1990; 33(6): 1601–10.

18. Altman RD, Manjoo A, Fierlinger A, Niazi F, Nicholls M. The mechanism of action for hyaluronic acid treatment in the osteoarthritic knee: A systematic review. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2015; 16(1): 1–10.

19. Altman R, Asch E, Bloch D, Bole G, Borenstein D, Brandt K, et al. Development of criteria for the classification and reporting of osteoarthritis:

Classification of osteoarthritis of the knee.

Arthritis Rheum. 1986; 29(8): 1039–49.

20. Zhang W, Doherty M, Peat G, Bierma-Zeinstra SMA, Arden NK, Bresnihan B, et al. EULAR evidence-based recommendations for the diagnosis of knee osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010; 69(3): 483–9.

21. Brown C, Cooke TD, Daniel W, Greenwald RGR, Hochberg M, Howell D, et al. The American College of rheumatology reporting of osteoarthritis of the hip. Arthritis Rheum. 1990;

33(6): 1601–10.

22. Runhaar J, Özbulut Ö, Kloppenburg M, Boers M, Bijlsma JWJ, Bierma-Zeinstra SMA.

Diagnostic criteria for early hip osteoarthritis:

first steps, based on the CHECK study.

Rheumatology. 2021; 1(1): 1–7.

23. Nieminen MT, Casula V, Nevalainen MT, Saarakkala S. Osteoarthritis year in review 2018: imaging. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2019;

27(3): 401–11.

24. Culvenor AG, Engen CN, Øiestad BE, Engebretsen L, Risberg MA. Defining the presence of radiographic knee osteoarthritis: a comparison between the Kellgren and Lawrence system and OARSI atlas criteria. Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy. 2015;

23(12): 3532–9.

25. Reichmann WM, Maillefert JF, Hunter DJ, Katz JN, Conaghan PG, Losina E. Responsiveness to

change and reliability of measurement of radiographic joint space width in osteoarthritis of the knee: A systematic review. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2011; 19(5): 550–6.

26. van der Oest MJW, Duraku LS, Andrinopoulou ER, Wouters RM, Bierma-Zeinstra SMA, Selles RW, et al. The prevalence of radiographic thumb base osteoarthritis: a meta-analysis.

Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2021; 29(6): 785–92.

27. Perrotta FM, Scriffignano S, de Socio A, Lubrano E. An Assessment of Hand Erosive Osteoarthritis: Correlation of Radiographic Severity with Clinical, Functional and Laboratory Findings. Rheumatol Ther. 2019;

6(1): 125–33.

28. Kim C, Nevitt MC, Niu J, Clancy MM, Lane NE, Link TM, et al. Association of hip pain with radiographic evidence of hip osteoarthritis:

Diagnostic test study. BMJ (Online). 2015; 351.

29. Oo WM, Linklater JM, Daniel M, Saarakkala S, Samuels J, Conaghan PG, et al. Clinimetrics of ultrasound pathologies in osteoarthritis:

systematic literature review and meta-analysis.

Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2018; 26(5): 601–11.

30. Hart HF, Stefanik JJ, Wyndow N, Machotka Z, Crossley KM. The prevalence of radiographic and MRI-defined patellofemoral osteoarthritis and structural pathology: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2017;

51(16): 1195–208.

31. MacKay JW, Low SBL, Smith TO, Toms AP, McCaskie AW, Gilbert FJ. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the reliability and discriminative validity of cartilage compositional MRI in knee osteoarthritis.

Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2018; 26(9): 1140–52.

32. Zhao X, Ruan J, Tang H, Li J, Shi Y, Li M, et al.

Multi-compositional MRI evaluation of repair cartilage in knee osteoarthritis with treatment of allogeneic human adipose-derived mesenchymal progenitor cells. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2019; 10(1): 1–15.

701

33. Ingegnoli F, Castelli R, Gualtierotti R.

Rheumatoid factors: Clinical applications. Dis Markers. 2013; 35(6): 727–34.

34. Qaseem A, McLean RM, Starkey M, Forciea MA, Denberg TD, Barry MJ, et al. Diagnosis of acute gout: A clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2017; 166(1): 52–7.

35. Saraiva AMCF, Pereira JP. Calcium Pyrophosphate Dihydrate Deposition in a Pseudarthrosis. Journal of Clinical Rheumatology. 2017; 23(3): 176–8.

36. Fpb K, Lra VDB, Buchbinder R, Rh O, Rv J, Pitt V. Self-management education programmes for osteoarthritis (Review). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014; (1).

37. Hall M, Castelein B, Wittoek R, Calders P, van Ginckel A. Diet-induced weight loss alone or combined with exercise in overweight or obese people with knee osteoarthritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2019; 48(5): 765–77.

38. Robson EK, Hodder RK, Kamper SJ, O’Brien KM, Williams A, Lee H, et al. Effectiveness of weight-loss interventions for reducing pain and disability in people with common musculoskeletal disorders: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Journal of Orthopaedic and Sports Physical Therapy. 2020; 50(6): 319–33.

39. Panunzi S, Maltese S, de Gaetano A, Capristo E, Bornstein SR, Mingrone G. Comparative efficacy of different weight loss treatments on knee osteoarthritis: A network meta-analysis.

Obesity Reviews. 2021; 22(8): 1–11.

40. Yamato TP, Deveza LA, Maher CG. Exercise for osteoarthritis of the knee. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016; 50(16): 1–146.

41. Østerås N, Kjeken I, Smedslund G, Rh M, Uhlig T, Kb H. Exercise for hand osteoarthritis (Review). Cochrane Database Syst Rev.

2017;(1):1–70.

42. Fransen M, Mcconnell S, Hernandez-Molina G, Reichenbach S. Exercise for osteoarthritis of the

hip. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews.

2014; 2014(4): 1–52.

43. You Y, Liu J, Tang M, Wang D, Ma X. Effects of Tai Chi exercise on improving walking function and posture control in elderly patients with knee osteoarthritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine. 2021; 100(16): 1–7.

44. Yan JH, Gu WJ, Sun J, Zhang WX, Li BW, Pan L. Efficacy of Tai Chi on Pain, Stiffness and Function in Patients with Osteoarthritis: A Meta-Analysis. PLoS One. 2013; 8(4): 1–9.

45. Hu L, Wang Y, Liu X, Ji X, Ma Y, Man S, et al.

Tai Chi exercise can ameliorate physical and mental health of patients with knee osteoarthritis: systematic review and meta- analysis. Clin Rehabil. 2021; 35(1): 64–79.

46. Lauche R, Hunter DJ, Adams J, Cramer H. Yoga for osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta- analysis. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2019; 21(9).

47. Wang Y, Lu S, Wang R, Jiang P, Rao F, Wang B, et al. Integrative effect of yoga practice in patients with knee arthritis A PRISMA- compliant meta-analysis. Medicine (United States). 2018; 97(31): 1–8.

48. van Ginckel A, Hinman RS, Wrigley VT, Hunter DJ, Marshall CJ, Duryea J, et al. Effect of cane use on bone marrow lesion volume in people with medial tibiofemoral knee osteoarthritis:

randomized clinical trial. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2019; 27(9): 1324–38.

49. Jones A, Silva PG, Silva AC, Colucci M, Tuffanin A, Jardim JR, et al. Impact of cane use on pain, function, general health and energy expenditure during gait in patients with knee osteoarthritis:

A randomised controlled trial. Ann Rheum Dis.

2012; 71(2): 172–9.

50. Carbone LD, Satterfield S, Liu C, Kwoh KC, Neogi T, Tolley E, et al. Assistive walking device use and knee osteoarthritis: Results from the health, aging and body composition study (Health ABC Study). Arch Phys Med Rehabil.

2013; 94(2): 332–9.

702

51. Rebbeca FM, Trevor B B, Dianne M B. Valgus Bracing for Knee Osteoarthritis: A Meta- analysis of Randomized Trials. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2014; 1(1): 1–32.

52. Cudejko T, van der Esch M, van der Leeden M, Roorda LD, Pallari J, Bennell KL, et al. Effect of soft braces on pain and physical function in patients with knee osteoarthritis: systematic review with meta-analyses. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2018; 99(1): 153–63.

53. Gueugnon M, Fournel I, Soilly AL, Diaz A, Baulot E, Bussière C, et al. Effectiveness, safety, and cost–utility of a knee brace in medial knee osteoarthritis: the ERGONOMIE randomized controlled trial. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2021;

29(4): 491–501.

54. Lu Z, Li X, Chen R, Guo C. Kinesio taping improves pain and function in patients with knee osteoarthritis: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. International Journal of Surgery. 2018; 59(September): 27–

35.

55. Ye W, Jia C, Jiang J, Liang Q, He C.

Effectiveness of elastic taping in patients with knee osteoarthritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2020;

99(6): 495–503.

56. Lin CH, Lee M, Lu KY, Chang CH, Huang SS, Chen CM. Comparative effects of combined physical therapy with Kinesio taping and physical therapy in patients with knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta- analysis. Clin Rehabil. 2020; 34(8): 1014–27.

57. Weleslassie GG, Temesgen MH, Alamer A, Tsegay GS, Hailemariam TT, Melese H.

Effectiveness of Mobilization with Movement on the Management of Knee Osteoarthritis: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. Pain Res Manag. 2021; 2021: 1267–76.

58. Bertozzi L, Valdes K, Vanti C, Negrini S, Pillastrini P, Villafañe JH. Investigation of the effect of conservative interventions in thumb carpometacarpal osteoarthritis: Systematic

review and meta-analysis. Disabil Rehabil.

2015; 37(22): 2025–43.

59. Bobos P, Nazari G, Szekeres M, Lalone EA, Ferreira L, MacDermid JC. The effectiveness of joint-protection programs on pain, hand function, and grip strength levels in patients with hand arthritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Hand Therapy. 2019;

32(2): 194–211.

60. Marotta N, Demeco A, Marinaro C, Moggio L, Pino I, Barletta M, et al. Comparative Effectiveness of Orthoses for Thumb Osteoarthritis: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-analysis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil.

2021; 102(3): 502–9.

61. de Almeida PHTQ, MacDermid J, Pontes TB, dos Santos-Couto-Paz CC, Matheus JPC.

Differences in orthotic design for thumb osteoarthritis and its impact on functional outcomes: A scoping review. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2017; 41(4): 323–35.

62. Wang H, Zhang C, Gao C, Zhu S, Yang L, Wei Q, et al. Effects of short-wave therapy in patients with knee osteoarthritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Rehabil. 2017; 31(5):

660–71.

63. Laufer Y, Dar G. Effectiveness of thermal and athermal short-wave diathermy for the management of knee osteoarthritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis.

Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2012; 20(9): 957–66.

64. Dantas LO, Breda CC, Mendes Silva Serrao PR, Serafim Jorge AH, Salvini TF. Cryotherapy short-term use relieves pain, improves function and quality of life in individuals with knee osteoarthritis – randomized controlled trial.

Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2017; 25.

65. Taru M, Maria F, Ryan Z. Pain management with acupuncture in osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2014; 14(312): 1–9.

66. Corbett MS, Rice SJC, Madurasinghe V, Slack R, Fayter DA, Harden M, et al. Acupuncture and