In the next two chapters, we focus on some of the most vulnerable patients with chronic diseases. 14 provides a brief summary of the main clinical implications of the literature reviewed in this volume.

Snapshot from the Field

Current Practice and Policy

Introduction: Definitions, Scope, and Impact of Nonadherence

Introduction

Managing a chronic illness is complicated; and as treatments have improved, the level of regimen complexity has only increased (Hood et al. 2009). Compliance with agreements is another compliance behavior that does not always receive the same attention as regime compliance (Schwartz et al. 2010).

Illness” versus “Disease”

At the same time, doctors often communicate exclusively in biomedical terms (Roter et al. 1997), which is associated with lower patient satisfaction (Ashton et al. 2003), rather than asking patients about their experiences and beliefs, which have been noted to improve the patient-provider relationship (Street et al. 2008). An important argument of this volume is that a lack of concordance between a patient's (and family's) disease-centered point of view and health care provider's disease-centered point of view leads to communication breakdowns that can significantly affect adherence.

Definition of Adherence and Nonadherence

Scope of the Problem of Nonadherence

It is not always easy to predict who may show a change in adherence behavior over time, although identifying risk factors for a decline in adherence is an active area of research (Schwartz et al. 2013; see ch. 12). A major advantage of this type of calculation is that it adds necessary precision to both clinical care and research (Modi et al. 2012).

The Current Healthcare System is Not Set Up to Promote Adherence to Chronic Illness Care

The use of many evidence-based assessment tools (Quittner et al. 2008) by pediatricians and primary care physicians is quite limited. One of the important barriers is the stigma (or perceived stigma) of seeing a psychologist (Schwartz et al. 2011).

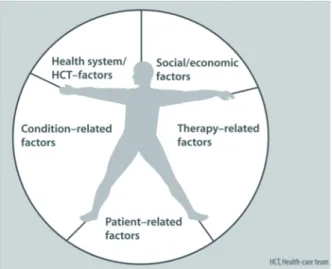

Nonadherence is a Multi-Factorial Problem

Mental health service providers are best equipped to address mental health disorders (which are sometimes associated with non-adherence), but do not necessarily have the expertise to address non-adherence itself. Helping families understand that most behavioral health psychological interventions specifically focus on adherence and other health-related behaviors can influence whether families follow through with recommended care.

Larger Societal Issues also Affect Adherence

8 and 9, but we do want to suggest here that we do believe that there may be possible ways to promote better compliance, even in these most vulnerable populations.

Summary

Meta-analysis of psychological interventions to promote medication adherence in pediatric chronic health conditions. Shemesh E, Annunziato RA, Arnon R, Miloh T, Kerkar N. Adherence to medical recommendations and transition to adult services in pediatric transplant recipients.

Conceptualizing Adherence

But what should be done when the perspectives of parents and children differ, when the parent wants one thing and the child wants another. What should be done when the perspectives of parents and children differ, when the parent wants one thing and the child wants another.

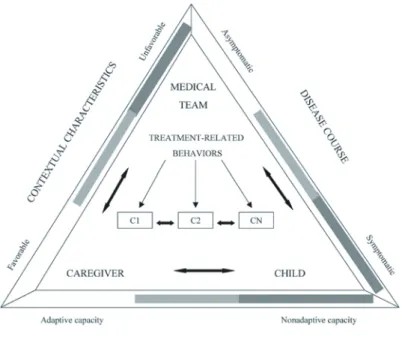

Stress and Coping Models of Illness Adaptation

Absence or passive coping refers to the avoidance or lack of any coping attempts (Rudolph et al. 1995). Not surprisingly, disengagement or avoidance coping has been associated with poorer adherence (eg, Reid et al. 1994).

Illness and Treatment Knowledge and Health Literacy

More recent models of managing chronic illness have focused on the dimension of control (Compas et al. 2012). Recent reviews of health literacy in the pediatric domain (Abrams et al. 2009; DeWalt and Hink 2009;

Health Beliefs

Children's/Youth's Beliefs The relationship between children's health beliefs and adherence is much less clear. Studies of youth with type 1 diabetes have generally shown positive effects of youth health beliefs on adherence (although see Urquhart et al. 2002).

Goal Setting

It is also important to recognize that people often have competing goals themselves, requiring them to prioritize goals, and patients will often prioritize non-health-related goals over health-related goals. Therefore, “understanding and respecting patients' non-health-related goals” (Schwartz and Drotar 2006) is necessary for providers who wish to best assist their patients with adherence.

Self Regulation

It is highly likely that suboptimal self-regulation plays a role in the adherence problems of teenagers. The application of self-regulatory frameworks to compliance is also complicated by the fact that compliance behavior is not actually driven by long-term goals for many or even most individuals.

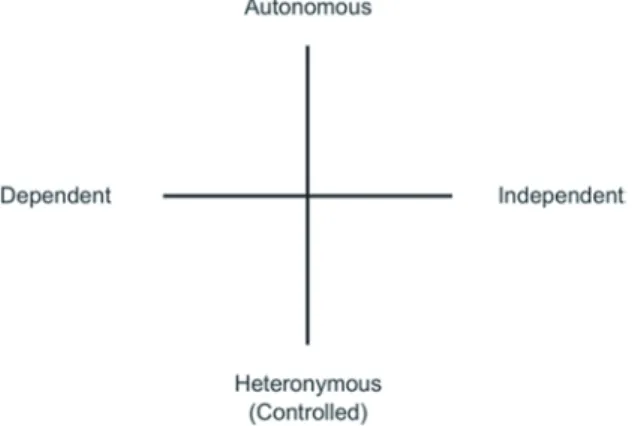

Motivation: Self Determination Theory

Indeed, as discussed later, most studies of adherence-promoting interventions show exactly this pattern, with initial benefit with poor maintenance of benefits over time (Cortina et al. 2013). Gillison et al. 2006) found associations between intrinsic (vs. extrinsic) motivators and perceived self-determination, and between self-determination behaviors and exercise in over 500 UK adolescents.

Putting It All Together

Family and youth factors associated with health beliefs and health outcomes in youth with type 1 diabetes. Social support and personal models of diabetes in relation to self-care and well-being in youth with type 1 diabetes.

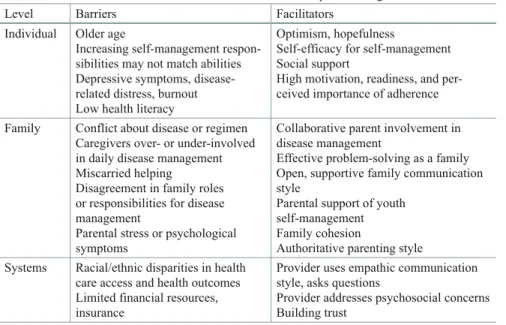

Barriers and Facilitators of Adherence

Clinical Factors

On the other hand, longer illness duration may provide more opportunity for individuals to identify helpful coping strategies and develop a sense of mastery over their treatments. It is possible that experiences such as these that emerge with longer illness duration may have a stronger, more direct association with changes in adherence behavior than illness duration itself.

Individual factors

Depressive symptoms may also color an individual's beliefs about the importance of treatment or motivation to adhere to prescribed regimens (Hilliard et al. 2014). Adolescents' awareness of their positive HIV status was associated with better adherence to daily antiretroviral medication (Bikaako-Kajura et al. 2006).

Family Factors

Health beliefs related to adherence include the extent to which an individual perceives his/her illness as a threat (DiMatteo et al. 2007; Garvie et al. 2011), one's readiness or motivation to engage touch on behaviors to manage the disease (MacDonell et al.). 2010), and one's sense of confidence or self-efficacy in their ability to perform the tasks of self-management (Ott et al. 2000).

Healthcare System and Provider Factors

Related to the patient-provider relationship is the concept of "white coat compliance [adherence]," a term that represents patients' increase in adherence immediately prior to a medical visit (Dusing et al. 2001). This pattern has been demonstrated for adherence to antiepileptic medication in youth with epilepsy (Modi et al. 2012) and for blood sugar measurement in young people with type 1 diabetes (Driscoll et al. 2011), which suggests that a certain expectation of the upcoming clinic visit may influence young people's adherence across diseases.

Cultural and Socioeconomic Factors

Depressive symptoms and glycemic control in adolescents with type 1 diabetes: mediating role of glucose monitoring. A review of peer influence on self-care and glycemic control in adolescents with type 1 diabetes.

Interventions to Promote Adherence

Innovations in Behavior Change Strategies

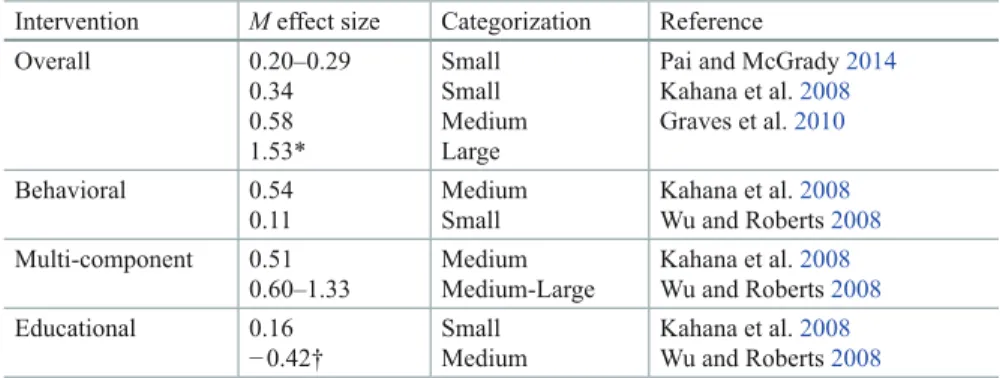

A meta-analysis of interventions to promote medication adherence in youth with type 1 diabetes found that the interventions that had the greatest impact on diabetes control tended to be multicomponent interventions that focused on adherence behaviors in combination with emotional, social, or familial processes related to diabetes management. Hood et al. 2010). Of note, the patterns emerging for improving medication adherence largely also translate into improvements in health outcomes (Graves et al. 2010; Pai and McGrady 2014).

Family-Focused Interventions

Although there is variation in the format, content, length, and other details of adherence interventions, nearly all meta-analyses and reviews conclude that behavioral and multicomponent interventions have the greatest impact on improving adherence, for both acute and acute therapies . Wu and Roberts 2008) and chronic medical conditions (Dean et al. 2010; Graves et al. 2010; Kahana et al. 2008; Lemanek et al. 2001). Other beneficial components of interventions include: making interventions disease specific (Wysocki et al. 2006); tailoring the content to the developmental level of young people; involving family members in the intervention; and making interventions more accessible by offering them at home, at school or through technology (Salema et al. 2011).

Recent Innovations in Adherence Interventions

Like electronic monitoring feedback, MI is often integrated into multicomponent interventions (Flattum et al. 2009; Seid et al. 2012). For example, Bean et al. 2014) used a two-session MI intervention with youth in a multidisciplinary treatment program for pediatric overweight/obesity.

Provider-Based Intervention Delivery

Researchers have also evaluated the impact of training pediatric providers in MI (Bean et al. 2012; Lozano et al. 2010). However, these relatively short trainings are often insufficient for healthcare providers to achieve competency in the approach (e.g. Bean et al. 2012), and there are no data to date on long-term effects or direct effects on patient outcomes.

Technology, eHealth, and mHealth

Targeting Interventions to the Highest Risk Patients

Many of these hospitalizations are the result of nonadherence to treatment and are therefore to some extent preventable (Schwartz et al. 2010). Preliminary data show that the program significantly reduces hospitalizations and healthcare costs (Harris et al., 2014).

Summary and Conclusions: Adherence Promotion in Clinical Practice

Interventions with adherence-promoting components in pediatric type 1 diabetes: meta-analysis of their impact on glycemic control. Association of disease, adolescent and family factors with medication adherence in pediatric inflammatory bowel disease.

The Importance of Development: Early and Middle Childhood

The remainder of the chapter then focuses on developmental considerations in disease management in early and middle childhood. The transition to early adulthood is a complex issue beyond the scope of this book.

The Role of Temperament

More important than age itself is (1) the onset of puberty, which heralds adolescence, a period of development qualitatively different from earlier childhood, and (2) the transition to young adulthood, especially when the child leaves home and is more or less busy . his own Less critical but still important are the transitions that accompany changes from elementary to middle school and from middle school to high school.

Chronic Illness in Early Childhood: Trust and Exploration

The struggle to come when called ends up taking precedence over receiving the treatment itself, which in some cases is completely forgotten. Parents' desperation in these cases can lead to a child digging in her heels even more.

Early School-Age Children: Developing Competence

On the other hand, it can be even more stressful for a parent if her child needs to eat for medical reasons, such as to ensure calorie intake, or shortly after a child with diabetes has received an insulin injection (Anderson and Schwartz 2014) .

Older School-Age Children: Where Do I Fit In?

Psychosocial risk screening of children newly diagnosed with type 1 diabetes: a training tool for health professionals. A critical review of the literature on fear of hypoglycemia in diabetes: implications for diabetes management and patient education.

Adherence in Adolescence

Indeed, adolescent morbidity and mortality is primarily attributable to risk-taking and health risk behaviors such as alcohol and drug use and reckless driving (Kann et al. 2013). In this chapter, we argue that these phenomena are related—that nonadherence and risk-taking are both largely attributable to the normal neurodevelopmental changes that occur during adolescence and to the consequent changes that occur in the parent-child relationship.

Adolescence—Definition

Adolescence is associated with an increase in sensation-seeking and reward-seeking behaviors, which underlie many common risk-taking behaviors in teens. Together, these factors create a “perfect storm” of increased risk-taking and increased risk-taking opportunities, with serious consequences for compliance.

Nonadherence as Risk-taking Behavior

In youth with diabetes, hormonal changes may also cause blood sugar levels to rise while insulin sensitivity decreases (Amiel et al. In youth with chronic illness, nonadherence to the medical regimen could potentially be added to this list of health risk behaviors.

Two Paths to Risk-taking

According to the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance study (Kann et al. 2013), the leading causes of morbidity and mortality among youth in the United States are related to six health risk behaviors: (1) behaviors that contribute to unintentional injury and violence; (2) tobacco use; (3) use of alcohol and other drugs; (4) risky sexual behavior; (5) unhealthy diet; and (6) physical inactivity. As we will see in the next section, current research in both developmental neurobiology and cognitive psychology supports this dual view.

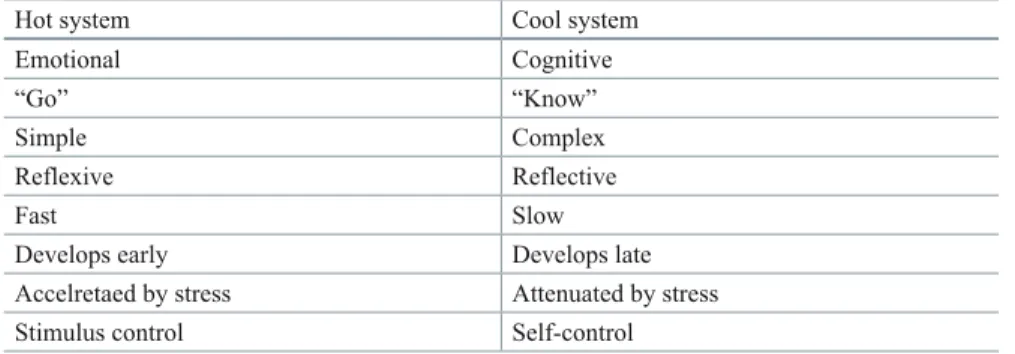

Neurodevelopmental Changes in the Adolescent Brain

It can even be said that increased activity in the social-emotional network increases behavioral readiness to take risks (Pomery et al. 2009). There is accumulating evidence that the default network can be disrupted by poorly controlled type 1 diabetes (Kaufmann et al. 2011;

Clinical Implications of the Neurodevelopmental Evidence

Neuroimaging studies have shown that the default network is only sparsely connected or fragmented in children (Fair et al. 2008) and likely undergoes significant developmental change through adolescence (Blakemore 2012). The default network is activated during resting but awake states and deactivated during goal-directed activity (Broyd et al. 2009).

Cognitive Factors in Adolescent Decision-making

Compared to adults, adolescents were slower to make decisions about “bad ideas” and were more likely to show activation in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, a decision-making area of the brain (Baird et al. 2005). Do adolescents engage in this kind of rational risk thinking when considering whether to skip an insulin dose or forgo respiratory therapy.

Risk Perceptions

In support of this, data suggests that when adolescents have positive experiences with behaviors such as drinking alcohol, they are more likely to engage in those behaviors in the future (Goldberg et al. 2002). Specifically, the more favorable the image, the more likely a youth will engage in that behavior (Gibbons et al. 2003).

Stress and Adherence

There is some evidence that explicit, fear-inducing images of the negative effects of smoking can result in avoidance of the message or in "psychological reactance" (Brehm 1966), a motivational state in which a person reacts against a message to maintain a feeling. of freedom and autonomy (see for example Erceg-Hurn and Steed 2011). However, the majority of research shows that even extremely explicit negative images are powerful motivators for change among both youth and adults (Hammond 2011).

Changes in Parenting and Social Support

Summary and Conclusions

Earlier development of the accumbens relative to the orbitofrontal cortex may underlie risky behavior in adolescence. Peer influence on risk-taking, risk preference, and risky decision-making in adolescence and adulthood: An experimental study.

The Role of Parents

Parent Involvement

Parenting Styles

In general, authoritative parenting has been associated with better outcomes, both in terms of overall child development and functioning (Barber et al. 2005), as well as in relation to adherence and chronic disease control in younger children ( eg, Davis et al. Results for parental control are more complicated, depending on the child's stage of development (Butler et al. 2007), how control is defined, and especially how it is perceived (Wiebe et al. 2005). .

Parental Control

Parental monitoring, arguably a less excessive form of limit setting, has consistently been found to be associated with better regimen adherence (eg, Ellis et al. 2007). In contrast to behavioral control, psychologically controlling behavior has consistently been found to be detrimental to children's general well-being (eg Barber et al. 2005).

The Transactional Nature of Parenting

Miscarried Helping

Racial/Ethnic Differences in Parenting

Other studies suggest that there may be a subgroup of African American parents who have a mixed parenting style (a combination of strict and harsh control, but emotionally warm—what the authors called "tough love") who may be equally effective (Brooks-Gunn and Markman 2005). In a study of children with type 1 diabetes (Davis et al. 2001), African American parents were significantly higher in tight control and their children had poorer glycemic control, but parenting was not associated with glycemic control when race/ethnicity was entered into the analyses.

Parenting Stress

Few studies have examined racial/ethnic differences in parenting and their relationship to medication adherence or chronic disease management.

Positive Parenting Can Reduce Risk

Evidence-Based Parenting Interventions

Brief report: posttraumatic stress disorder in parents of children with newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes. Generic and diabetes-specific parent-child behavior and quality of life in youth with type 1 diabetes.

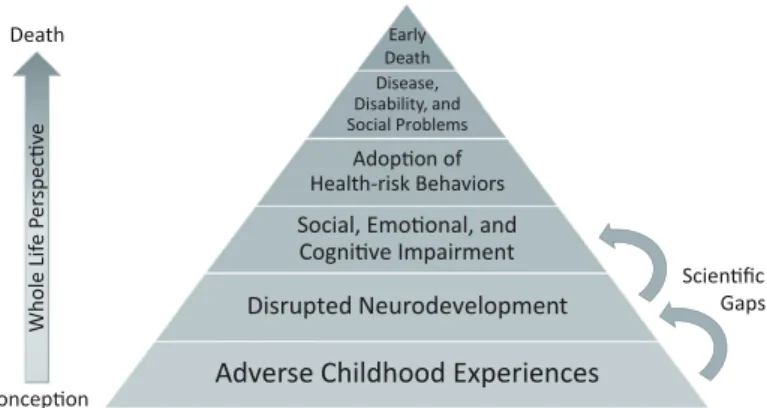

Poverty, Stress, and Chronic Illness Management

But even if all of the above changes were fully implemented, they would not address one of the fundamental differences between poor and higher-income families: significant exposure to often severe social and environmental stress. As Evans (2004) noted, “Cumulative rather than single exposure to a confluence of psychosocial and physical environmental risk factors is a potentially critical aspect of the child poverty environment….

Toxic Stress

Toxic stress causes chronic overactivation of this system, which can lead to dysregulation of the stress response itself (resulting in poor stress responses in the future), and in severe cases can damage the central nervous system, affecting cognitive, social and emotional development. Exposure to extreme stress alters the structure and function of the amygdala, hippocampus, and prefrontal cortex (McEwen and Gianaros 2011), resulting in increased anxiety and decreased mood and memory control (Shonkoff et al. 2012).

Adaptation to Stress

According to Child Trend's analysis of data from the National Survey of Children's Health 2011/2012 (2013; http://www.childtrends.org), approximately 12-14% of poor and near-poor children experienced three or more ACEs, compared only 6% of children are twice as poor as or higher. The role of parents in moderating stress further highlights the importance of parenting for the adjustment (and ultimately adherence behavior) of children with chronic illness, as discussed further below.

Does Toxic Stress Contribute to Nonadherence?

As noted above, adolescents (and adults) with a history of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) are more likely to abuse alcohol and drugs (Anda et al. 2006). Other risk behaviors associated with early ACEs include smoking, overeating, promiscuous sex (Shonkoff 2010) and gambling (Scherrer et al. 2007).

Managing Toxic Stress

Memory impairment is of particular note, as the most common cause of medication nonadherence is forgetting (eg, Buchanan et al. 2012). It has been suggested that these behaviors all have the function of reducing stress (which has been termed behavioral allostasis; Garner 2013; see also Rothman et al. 2008).

Comorbid Risk

Conclusions

The American Academy of Pediatrics has identified toxic stress as a priority area (Garner et al. 2012), and a task force is currently developing guidelines for prevention, screening, and treatment, as well as parent education. Early childhood adversity, toxic stress, and the role of the pediatrician: translating developmental science into lifelong health.

Racial/Ethnic Disparities and Adherence

Overview of Health Disparities among Racial/Ethnic Minority Children

Unfortunately, minority children experience disproportionately adverse outcomes in a number of chronic conditions (Berry et al. 2010). American Indian and African American children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) have 4 times higher odds of school failure and 11 times higher odds of family burden compared to non-minority children (Ezpeleta et al. 2001).

Adherence among Racial/Ethnic Minority Children

Given the widespread disparities in nonadherence, we emphasize that improving adherence among minority children is an essential goal to help eliminate disparities in chronic condition outcomes. Below we describe the potential of improving parent, adolescent, and provider communication for improving adherence among minority children.

Parent- and Adolescent-Provider Communication and Adherence

African American children showed higher non-adherence to antiretroviral treatment for human immunodeficiency virus (Naar-King et al. 2013) and to medication for hypertension (Eakin et al. 2013).

Factors that Influence Communication Between Minority Families and Healthcare Providers

Finally, a number of studies have shown racial/ethnic differences in health beliefs and perceptions. For example, there are racial/ethnic differences in parents' and adolescents' beliefs about the causes of children's mental health conditions and treatment options (Bussing et al.

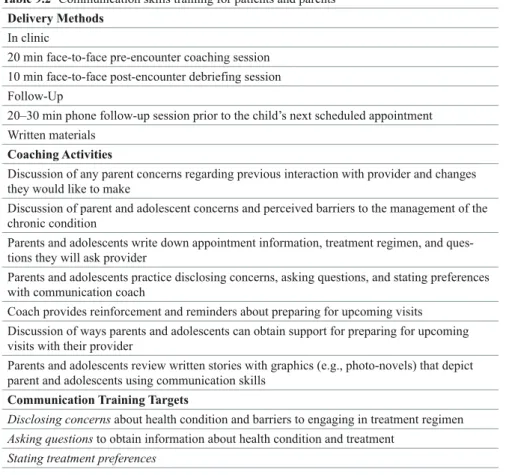

Promoting Effective Parent-Provider and Adolescent- Provider Communication

For example, information about chronic health conditions during coaching sessions can be tailored to the level of health literacy of parents and adolescents. Recommendations for improving communication among vulnerable families include communication skills training for providers and coaching interventions for parents and adolescents.

Implications for Policy and Practice

Rethinking Self-Management

The Push for Independent Self-Care

In children with HIV, a descriptive study found that a quarter of patients aged 8–18 reported having full responsibility for their own medication, and this percentage increased with age (Naar-King et al. 2009). A recent study involving focus groups and interviews with 143 young adults with special health needs, their family members, and their health care providers concluded that preparing youth for transition "should begin in childhood or at the time of diagnosis" and that "provided can help facilitate the transition by encouraging families to envision their child's future and promote medical independence” (Reiss et al. 2005).

Current Practice Recommendations

There is a lot of evidence that 12 is seen as the "magic number" when it comes to transferring responsibility for managing the disease from parent to child. Twelve is also the age at which many writers believe the process of preparing young people for the transition to adult health care should begin.

The Evidence for Continued Parent Involvement

It is well known that nonadherence to medication is the most common cause of premature graft loss in youth (Dobbels et al. 2010; Furthermore, a decline in parental involvement and shift in responsibility can be particularly disastrous for youth who already have difficult with compliance (Seiffge-Krenke et al. 2013).

Developmental Readiness

Oliva et al. 2013; Shemesh 2004), and adolescents who have primary responsibility for medication adherence are more likely to be nonadherent than those whose parents are responsible (74 versus 56% in one study; Simons et al. 2009). Instead, this is a pattern that has been observed in many diagnostic groups, including asthma (Bender et al.

Barriers to Parent-Child Collaboration

Thus, high parental monitoring likely helped keep children with less responsibility out of the ER. The appropriate and under-responsible groups both had good adherence and glycemic control.).

The Catch-22 of Parent Involvement

Parents may also withdraw from disease management if conflict results, despite the fact that this type of conflict is normal and may actually be an important way in which parents and teenagers renegotiate their relationship around self-care (Holmbeck 1996). Interventions focused on teaching families conflict management skills have proven to be an effective way to promote family "teamwork" in children with various chronic illnesses and their parents (Anderson et al.

The Most Vulnerable Patients

For these types of problems, an educational and remedial approach (e.g. as recommended by Annunziato et al. 2008) is unlikely to prove very effective (Kahana et al.). families of adolescents with type I diabetes.

Healthcare Partnerships

Autonomy-Supportive Parenting

Autonomy-Supportive Healthcare

The basic idea of autonomy-supportive is that it is the patient (and often his/her patient). Deci and Ryan (2012) suggest the importance of providing health information in a deliberately neutral manner so that it is not perceived as coercive and is instead perceived as coercive. presented as a means to increase the patient's ability to make fully informed choices.

Provider-Patient Communication is the Key to Building and Maintaining Partnerships

Information that is presented in a way that acknowledges the difficulty of the action or decision (for example, starting to exercise or quitting smoking), and that conveys respect for the patient's ultimate decision (whatever it may be), is likely to be more impactful to have. more effective (because it supports autonomy) than communication that gives patients the feeling that they are being controlled. To promote good communication skills, training programs should emphasize: effective listening skills (Drotar et al. 2010), shared decision-making (Charles et al. 1997; Drotar et al. 2010), autonomy support (Deci and Ryan 2012) and cultural competence (Burgess et al. 2007), with the ultimate goal of building effective partnerships with families.

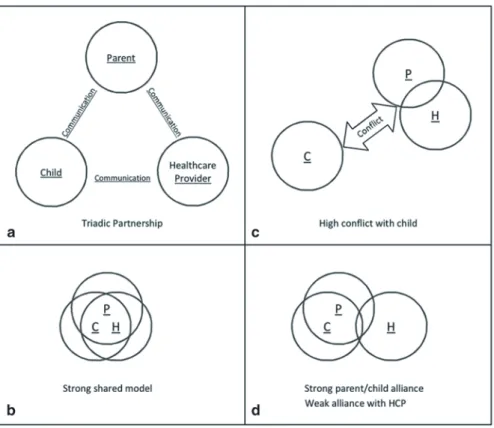

Patient-Parent-Provider Teamwork: The Healthcare Partnership or Therapeutic Triad

Ultimately, families are the primary decision makers for day-to-day care, whatever the provider wishes (Drotar et al. 2010). Collaborative decision-making, when involved, usually occurs only after the initial treatment regimen is established (Drotar et al. 2010).

Developing a Shared Model of Illness

This does not mean that empirically minded professionals should accept alternative treatments per se, but they should create an environment in which the patient is comfortable enough to discuss treatment issues without feeling judged. The overlap between the circles is intended to represent the strength of the alliance, which in turn can be taken as an indirect measure of the degree to which partners share a common disease pattern.

Coordination of Care

The Role of Psychologists

Physician behavior in pediatric chronic disease care: association with health outcomes and treatment adherence. Collaborative decision making and promoting adherence to treatment in the management of pediatric chronic disease.

Looking Ahead

A Comprehensive Behavioral Health Model for Promoting Pediatric Adherence

Screening for Nonadherence in Pediatric Patients

Is there a way to predict who is at risk for DKA so that preventative measures can be taken? The idea is to predict who may be at increased risk so that preventive measures can be taken.

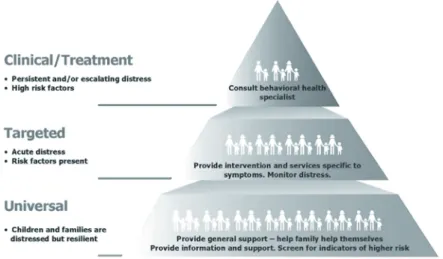

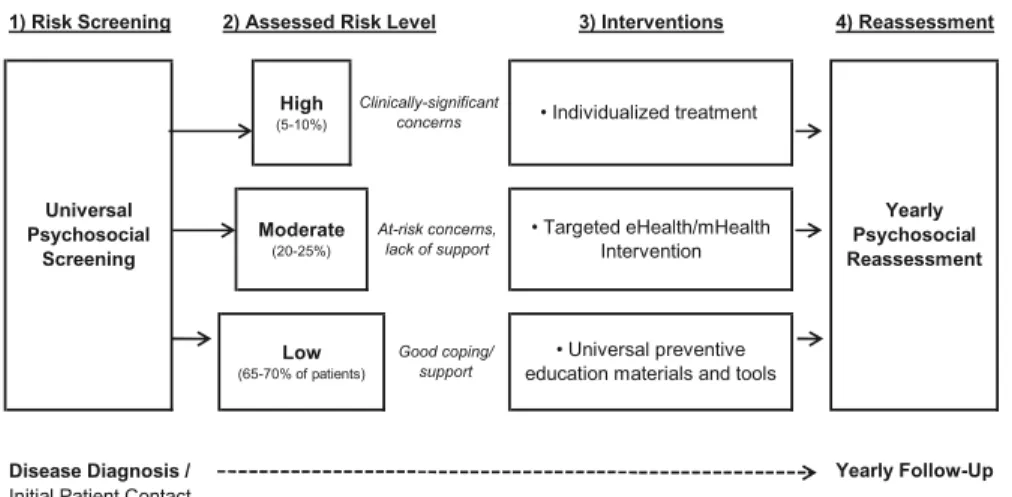

The Importance of Prevention

Risk screening allows potential problems to be addressed before they are entrenched or severe, and thus will be more amenable to intervention (Gates 2001; Modi et al. 2013). Second surveillance screening of established patients is essential to identify who may be nonadherent or struggling with other issues that may affect adherence, such as depression.

Criteria for Effective Screening

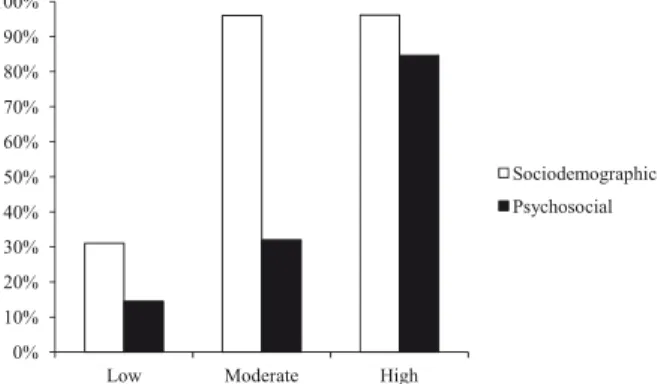

These different domains have been organized into a “simple model” of risk of nonadherence (Fig. 12.2) that was used to guide the development of the PRiSM screening tools (for a detailed description of the initial development of the screening tool, see Schwartz , Axelrad et al. 2011). PRiSM has been field tested for feasibility and acceptability (Schwartz, Cline et al. 2011) and is currently being validated.

Concerns About Screening

For example, in surveillance studies we have conducted in established type 1 diabetes patients, we have found the following pattern in some patients: high HbA1c, parent and/or self-report of feeling overwhelmed by diabetes, no other concerns (e.g., non-adherence, no depression or behavioral problems, etc.) and no interest in psychological follow-up. In these cases we have recommended further consultation with the treating endocrinologist about simplifying the medical regimen, and so far anecdotal evidence suggests that this has been helpful, although more data are needed to know if this pattern is indeed so. Real.".

Tips to Assessing for Nonadherence

Depressive symptoms in children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes: association with diabetes-specific characteristics. Feasibility, acceptability and predictive validity of a psychosocial screening program for children and youth newly diagnosed with type 1 diabetes.

A Comprehensive Behavioral Health System for Identifying and Treating Nonadherence

Overview of the Comprehensive Model

For the system to be successful, it would need mechanisms to (1) review/assess risk and current problems; (2) triage to different interventions based on the overall level of assessed risk (low, moderate, or high) and according to the type of risk (sociodemographic; child, caregiver, or family functioning problems; disease concerns); and (3) regular reassessment. Patients with high acuity (eg, suicidal ideation) should probably be reviewed outside of the system presented here.

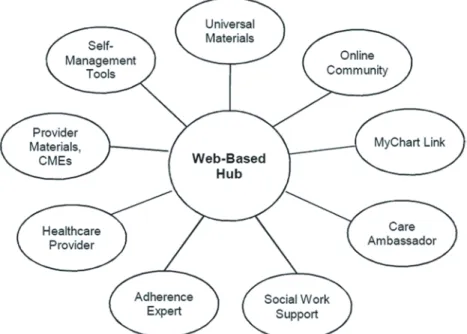

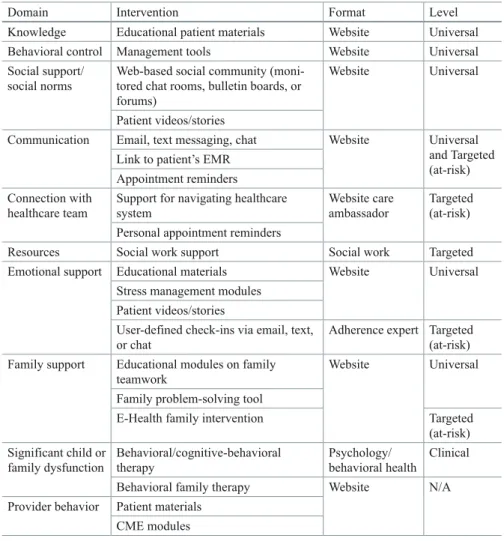

A Web-Based System for Evidence-Based Intervention at All Levels of Risk/need

In addition to the universal materials and tools suggested above, patients at participating clinics can also be given access to tools and support related to their medical scheme and the hospital/clinic where they receive their treatment. Of course, security concerns in the design of this system would be paramount, to ensure that only the patient (and his/her legal guardians) have access to the information.

Targeted Services

To conduct follow-up screenings, an automated screening tool could be built into the integrated system and accessible through the hub. These factors can in turn be included in the action plan that the patient develops under the guidance of the program.

Keeping Patients Connected

Training for Healthcare Professionals

Patient education materials that healthcare providers can use with their patients on a range of adherence-related topics.

Summary of the Integrated Behavioral Health System

The behavioral health model proposed here represents an innovative attempt to proactively address the widespread problem of suboptimal medication adherence. By addressing multiple factors that support adherence more or less simultaneously, we believe that these types of integrated systems have a better chance of producing changes in overall adherence.

Pulling it All Together: Clinical Conclusions

Recent findings from developmental neurobiology strongly support the idea of a maturity gap in adolescence, between well-developed reasoning skills but poor ability to use these skills, especially in social situations and in the "heat of the moment." The evidence also points to overreactivity in the social-emotional reward system with a concomitant increase in (often risky) reward-seeking behavior that the cognitive control system is not yet able to effectively regulate. Most patients and families will have adequate coping and support, and they can be provided with universal educational materials and disease management tools to help promote adherence.