We compared those who participated in the training program with those who did not using propensity score matching and difference-in-difference method. The results show that experience in the training program was significantly associated with post-training evaluation and promotion likelihood, suggesting that improving interpersonal skills through participation in off-the-job training programs can improve worker's post-training performance and lead to future promotion. The opinions expressed in the papers are solely those of the author(s), and do not represent those of the organization(s) to which the author(s) belong(s) or the Research Institute for Economics, Trade and Industry.

The aim of this training program is to promote substantive communication between employees, not only within the department, but also across departments within the company. The employees who participate in this program, the so-called 'coaches', are also immediately given the opportunity to put into practice what they have learned. This means that in 2014 a majority of middle managers participated in the coach training program.

According to the internal study, 82 percent of the coaches assigned to this training program realized the improvement in the communication between the departments and their own interpersonal skills, although this is still anecdotal evidence. The tasks for this training program may be endogenously determined by the observable characteristics of the participants. We selected the control group from the sample of those who did not participate in the leadership coaching training in 2012 or 2013. We selected the stakeholder control group from the sample of those who did not receive coaching sessions as stakeholders or participate in management. training as a coach in the period between 2012 and 2014.

For the coach analysis sample, we also exclude female employees because there were only a few female participants in the executive coaching training and their career is more likely to be interrupted by family events.

Descriptive Statistics

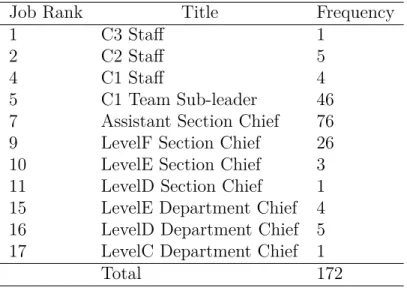

Our restrictions result in final samples that have 183 employees in the treatment group and 378 employees in the unmatched comparison group.

Empirical Strategy

This paper examines the effect of managerial coaching training using propensity score matching and variance-in-difference to correct for these endogeneity biases. The propensity score matching method allows us to compare those who participated in the management coaching training with those who had not yet participated to correct for bias due to confounding factors. We match those with similar observed characteristics in the comparison group to the treatment group using the predicted probability (propensity score) for training participation.

Therefore, we use propensity score matching with the difference-in-difference method (PSM-DID) to control for remaining unobservable characteristics (Heckman et al. 1998, Blundell and Costa Dias 2002). Because management training for trainers is intended to identify future executive candidates and enhance their managerial skills, we must focus on the effect on those employees who are actually targeted by the training program. As mentioned above, we aim to estimate ATT and this estimator is presented as the following equation.

E(Y1|D=1) is the expected value of the outcome, which includes the assessment score and the incidence of advancement in this contribution when participating in the training program. When E(Y0|D=1) =E(Y0|D=0) is withheld, non-training participants can serve as an appropriate control group. Conditioning on the value of the individual attribute X, which is a covariate, means that the joint distribution of the potential outcome Y1 in case of participation in training (D=1) and the potential outcome Y0 in case of non-participation in training does not depend on the result of participation in training.

Equation (3) is called a general support assumption, which means that there are employees who did not participate in the training but have similar characteristics to those who did. Under the assumption (2), with the conditioning of the participation probabilityPr(D=1|Xi), whether employees participate in the training or not becomes independent of potential outcomes Y1 and Y0. In the case of analysis for the stakeholders, female dummy is also added to the above control variables.

We estimate the propensity score in equation (4) and subsequently perform the estimation for ATT using propensity score matching DID (PSM-DID). P(Xi,t−1),P(Xj,t−1) . ) the weight is placed on the matched untreated employee, which corresponds to the treated employee. N represents the number of participants in the treatment group and ∆Yi,t+s(1)=Yi,t+s−Yi,t−1represents the difference in outcomes between year (t+s) and year (t-1) ).

Effect of the managerial coaching training on the coachers

These results imply that those who had a higher evaluation score were likely to be selected as the participants for the management coaching training as a coach. By comparing the mean values of the pretreatment characteristics between the treatment and the corresponding control group, there are no significant differences in the two groups. For evaluation scores, in all post-treatment years, the values of ATT are positive and those of the evaluation in June and those in December 2013 are statistically significant.

The values of ATT on promotion are all significantly positive in all posttreatment years. These results indicate that leaders who received leadership training tended to perform significantly better than comparable leaders who did not during the post-treatment period. The superiors who recommended the managers for the coaching training may have private information about their subordinates' managerial capacity that is not fully captured by the observables but would be reflected in the error term in the performance equation.

The error term would then be related to training participation, leading to endogenous bias. Or, the superiors who evaluated or promoted the treatees may be the ones who recommended them for training in the first place. In this case, bias in their evaluation (ie favoritism) as well as private information would cause participation and performance measures to be correlated with each.

Although training has not yet begun for most as of June 2012, there is a significant difference in performance evaluation as early as June 2012. The skill difference recognized by superiors may have emerged in the evaluation. Nevertheless, our results are consistent with management's perception that management coaching training is effective in increasing participant retention.

First, managers who were trained were more likely to be promoted or transferred to other departments, causing their performance to deteriorate during the first year on the new job. Although we make reasonable efforts to adjust for the dip as discussed earlier, the adjustment in a linear form may not be sufficient to correct the short-term bias. Second, our control group consists of managers who did not receive managerial coaching training in 2012 and 2013, and a significant portion of them received training in 2014, which would have made the ATT in December 2014 smaller.

Effect of the managerial coaching training on the stake- holders

It may seem that a competent person who does not hesitate to work long hours is likely to be asked to take on the role of a stakeholder. We now estimate the average effect of receiving coaching sessions on evaluation scores and promotion by comparing the treatment group and the matched control group. According to Table 8, which shows the result of the balancing test, there are no significant differences between the treatment groups and the matched control groups.

For evaluation, the value of ATT in all years after treatment is positive and those of the evaluation in December 2012 and 2013 are statistically significant. These results are consistent with management's view that the coaching training also helps stakeholders perform better by developing skills relevant to current tasks. Similar to our analysis of the effect on coaches, the effect on stakeholder performance may be overestimated because coaches who selected the stakeholders for coaching sessions may have private information about the latter's growth potential, which affects the selection and the error term in the performance would cause. equation that needs to be correlated.

Therefore, the short-term impact of coaching sessions on stakeholders can be minimal at best. In this article, we explore the relationship between interpersonal skills training for selected employees and performance indicators, including evaluation and promotion probability. First, we present evidence of the effect of off-the-job training on productivity measures.

Second, interpersonal skills are considered increasingly important in an age of advanced information and communication technology, including artificial intelligence. Since coaching is a development method for interpersonal skills with a focus on solving short-term and job-specific problems through communication, it should be relatively easier to measure the effect of the training. We would like to show the early evidence of this kind of investment in human capital in the business environment.

First, since randomized assignment was not designed ex ante, propensity score matching alone would not have eliminated selection bias, since the superiors who have private information should have selected those likely to succeed in the future. Second, we limited our attention to relatively short windows (ie, two years) because almost all middle managers received the management training within five years. This limitation has made it difficult to examine the long-term effect of the training.

Headquarters×Job ranking Yes Headquarters×Job type Yes Location, Studying abroad Yes Age, Employment, Marriage Yes. Headquarters×Job ranking Yes Headquarters×Job type Yes Location, Studying abroad Yes Age, Employment time, Marriage, Female Yes.

Level 2

Level 8