ENGLISH SONGS AND THEIR INFLUENCE ON LONG-TERM VOCABULARY GAINS IN UTAR UNDERGRADUATES

CHERVON CHAN YEN WEN 19AAB06024

SUPERVISOR: MS. BHARATHI A/P MUTTY

SUBMITTED IN

PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR BACHELOR OF ARTS (HONS) ENGLISH LANGUAGE

FACULTY OF ARTS AND SOCIAL SCIENCE

JUNE TRIMESTER 2022 UALZ 3023 - FYP2 REPORT

ENGLISH SONGS AND THEIR INFLUENCE ON LONG-TERM VOCABULARY GAINS IN UTAR UNDERGRADUATES

CHERVON CHAN YEN WEN 19AAB06024

SUBMITTED IN

PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR BACHELOR OF ARTS (HONS) ENGLISH LANGUAGE

FACULTY OF ARTS AND SOCIAL SCIENCE

JUNE TRIMESTER 2022

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study would not have been possible without the guidance and assistance from several parties. That said, I would like to take this opportunity to thank all the parties who have helped me throughout this research.

Firstly, I would like to thank my supervisor, Ms. Bharathi A/P Mutty, for her guidance and feedback. Her support was extremely crucial and valuable in making this research possible. I would also like to thank my family members for supporting me through thin and thick. Finally, I would like to show my gratitude to my amazing friends and the helpful participants for sharing their opinions with me.

I am much obliged that I was given the opportunity to conduct this research and I appreciate all contributions towards this study.

ABSTRACT

Non-native English learners often struggle to retain newly learnt vocabulary. Songs have attributes suitable for vocabulary learning—repetitive and conversation-like—this shows their high potential of being a vocabulary learning tool outside of classrooms. Various past research demonstrate the effectiveness of songs for vocabulary learning and retention in classroom settings, but little study can be found on the impact of songs on vocabulary

learning outside of classrooms. It is unclear how listening to English songs and the repetition of these songs will impact the vocabulary gains of ESL undergraduates outside of classrooms.

100 English language and English education undergraduates from Universiti Tunku Abdul Rahman (UTAR), Kampar Campus, Malaysia, were evenly and randomly assigned into short- term and long-term groups. The present study presents several perceptions of undergraduates on English songs and the effects of repetition of songs on long-term vocabulary gains. The results indicated that (a) the perception of undergraduates on English songs could be categorised into the themes of tune and rhythm, English pronunciation, acquisition and retention of vocabulary, accessibility, creates a low-stress environment, and prefer other learning methods, (b) there is little significance between repetition on vocabulary gains, and (c) one-week duration after the listening session posed little significance between repetition and long-term vocabulary gain retention.

Keywords: English songs, vocabulary learning, vocabulary acquisition, repetition, vocabulary retention, Krashen’s Input Hypothesis, Forgetting Curve

DECLARATION

I declare that the material contained in this paper is the end result of my own work and that due acknowledgement has been given in the bibliography and references to ALL sources be they printed, electronic or personal.

NAME: CHERVON CHAN YEN WEN STUDENT ID: 19AAB06024

SIGNATURE:

DATE: 07/09/2022

APPROVAL SHEET

This research paper attached hereto, entitled “English Songs and Their Influence on Long- Term Vocabulary Gains in UTAR Undergraduates” prepared and submitted by Chervon Chan Yen Wen in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Bachelor of Arts (Hons) English Language is hereby accepted.

_____________________ Date: _____________

Supervisor

Ms. Bharathi A/P Mutty

LIST OF FIGURES

Figure 1 Conceptual Framework ... 42 Figure 2 Average Long-term Vocabulary Gain Retention of Undergraduates ... 51 Figure 3 Average Short-term Vocabulary Gain Retention of Undergraduates ... 53 Figure 4 Comparison of Repetition on Short-term and Average Long-term Vocabulary Gain Retention ... 54

LIST OF TABLES

Table 1 Lexical Frequency Profile of Song A ... 35

Table 2 Lexical Frequency Profile of Song B ... 37

Table 3 Target Single-Word Items and Their Collocations ... 37

Table 4 Paired Sample T-Test Between Short-Term Retention of Song A and Song B ... 52

Table 5 Paired Sample T-Test Between Long-Term Retention of Song A and Song B ... 53

Table 6 Independent Sample T-Test Between Short-Term Vocabulary Gain Retention and Long-Term Vocabulary Gain Retention of Song A ... 55

Table 7 Independent Sample T-Test Between Short-Term Vocabulary Gain Retention and Long-Term Vocabulary Retention of Song B ... 55

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS UTAR Universiti Tunku Abdul Rahman EFL English as a Foreign Language ESL English as a Second Language

VLT Vocabulary Levels Test

MUET Malaysian University English Test

IELTS The International English Language Testing System

CEFR The Common European Framework of Reference for Languages BNC/COCA British National Corpus/Corpus Contemporary American English VARK Visual, Aural, Read/write, and Kinaesthetic sensory

Contents

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ... 2

ABSTRACT ... 3

DECLARATION ... 4

APPROVAL SHEET ... 5

LIST OF FIGURES ... 6

LIST OF TABLES ... 7

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ... 8

Introduction ... 12

Background of Study ... 13

Problem Statement ... 15

Research Objectives ... 16

Research Questions ... 16

Operational Definitions ... 16

Conclusion ... 17

Literature Review... 18

Vocabulary Learning for Non-native English Learners ... 18

Songs in Language Learning Classrooms ... 21

Songs and Vocabulary Gains ... 23

Memory in Language Learning ... 25

Repetition and Retention ... 26

Repetition and Vocabulary Learning ... 27

Incidental Vocabulary Learning and Memory ... 28

Conclusion ... 29

Methodology ... 31

Theoretical Framework ... 31

Participants ... 32

Materials ... 34

Song A ... 35

Song B ... 36

Target Words ... 37

Instruments ... 38

Preliminary Questionnaire ... 38

Vocabulary Levels Test ... 38

Open-ended Questionnaire ... 39

Multiple-choice Test ... 39

Pilot Test ... 40

Procedure ... 42

Conceptual Framework ... 42

Data Collection and Analysis Technique ... 43

Conclusion ... 44

Results and Discussion ... 45

Undergraduates’ Perception of English Song Listening ... 45

Tune and Rhythm ... 45

English Pronunciation... 46

Acquisition and Retention of Vocabulary ... 47

Accessibility ... 49

Creates a Low-Stress Environment ... 49

Prefer Other Learning Methods ... 50

Effects of Repetition of Songs on Long-Term Retention of Vocabulary Gains ... 51

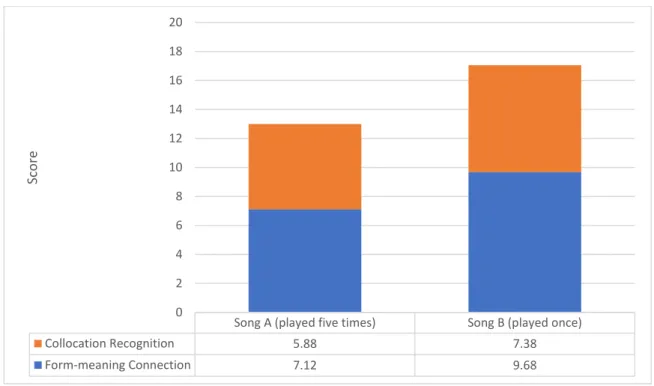

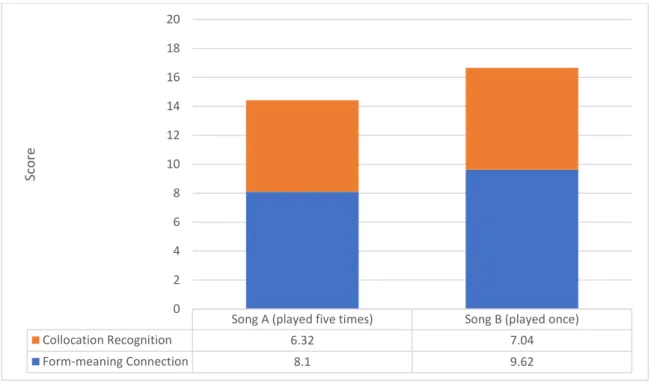

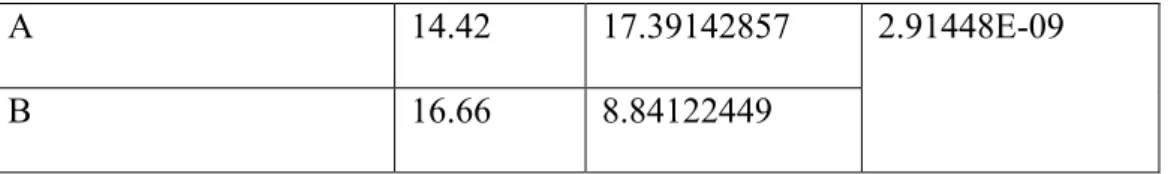

Repetition of Song on Long-Term Vocabulary Gain Retention... 51

Repetition of Song on Short-Term Vocabulary Gain Retention ... 53

Repetition of Songs on Vocabulary Gain Retention ... 54

Discussion ... 56

Conclusion ... 59

Conclusion ... 61

Limitations ... 61

Recommendations for Future Research ... 62

Implications of Study ... 63

Summary ... 64

References ... 65

APPENDIX A ... 74

APPENDIX B ... 83

APPENDIX C ... 88

APPENDIX D ... 93

Introduction

Humans have used songs to amuse themselves for a long time, it existed quite possibly as long or even longer than human speech (Shen, 2009). The noun “song” had historically been used to describe “voice, song, art of singing; metrical composition adapted for singing, psalm, poem”; the word originated from Old English and has roots from Proto- Germanic and Proto-Indo-European languages before gradually evolving into the spelling that we know of today (Etymonline, n.d.). In contemporary English, Oxford University Press (2021e) offers two main definitions under the headword song. The first definition being “a short poem or other set of words set to music or meant to be sung” and the second “the musical phrases uttered by some birds, whales, and insects, typically forming a recognizable and repeated sequence and used chiefly for territorial defence or for attracting mates”. In the first definition, it can be evidently understood that the presence of words in the musical composition is emphasised.

Myers (2016) stated that popular music—now known as pop music— in particular, is an ever-changing and widely misunderstood genre; it previously consisted of songs that were popular among the people but is now a genre that consists of various music that have the melody and structure of traditional pop. A study by Verboord and Brandellero (2018) analysed the globalisation and flow of popular music, the trends show that international pop music charts started becoming more Anglo-American oriented in the 1960s. According to Engh (2013) some of the earliest literature regarding the usage of music in language

acquisition occurred around the same time, this includes scholarly works by Bartle (1962, as cited in Engh, 2013), Richards (1969, as cited in Engh, 2013), and Jolly (1975, as cited in Engh, 2013).

Memory, on the other hand, is crucial to us humans when it comes to language

learning; learners need to utilise various memorising strategies to retain information related to

the targeted language (Everyday ESL, 2017). Students often use flashcards, notebooks, dual- language dictionaries, and the target language’s dictionary to comprehend and learn the meaning of words (Nemati, 2009). According to Walker (2015), students have difficulty in retaining knowledge, particularly vocabulary, of the targeted language; after interviewing some students, he deduced that they lack a systematic approach to vocabulary learning, which consequently led to their memory of the newly learnt clusters of words being forgotten.

While this study was based on the Latin language, this phenomenon is also prevalent in second language learning of other languages.

It is clear that songs and memory are both of great importance to humans, one to entertain ourselves and another for survival. However, songs can do more than merely entertain. In the following sections, songs and their role in language learning, particularly vocabulary learning, will be discussed.

Background of Study

Second language learning is a difficult, complicated, and long process; it takes plenty of commitment, involvement, physical, intellectual, and emotional response to successfully transmit or receive information in the target language (Brown, 2007). That being so, it is not surprising that only little people manage to achieve fluency in their target language when their learning solely occurs within the confinement of classrooms (Brown, 2007). When outside of a classroom, language learners may be exposed to television, movies, and songs of their target language; these mediums serve as the main input of the target language when learners are outside of formal learning settings (Pavia et al., 2019). A survey conducted across seven European countries showed that young L2 learners mainly get exposure to their target language through listening to songs and viewing television and movies.; on top of that, the time spent on these activities were three times more than of reading (Lindgren & Muñoz, 2013, as cited in Feng & Webb, 2020). Learning that occurs outside of a classroom or an

academic setting can be regarded as out-of-classroom learning (Stuart, 2018). Learning that occurs due to a learner’s own initiative without the assistance of other individuals, however, is known as self-directed learning (Mackey & Jacobson, n.d.). That said, the act of listening to music can be regarded as out-of-classroom self-directed learning.

In Malaysia, 2.9 billion songs are streamed on Spotify in a single year (Spotify AB, n.d.). Out of the 50 songs listed in the playlist Top Tracks of 2020 in Malaysia, 35 of them are listed as English songs (Spotify, 2020). This shows the high potential of English songs being an outside of classroom English language learning material. Songs have historically been viewed as a form of entertainment rather than a medium of learning; however, the usage of songs in English as second language learning classrooms is in no way a new concept (Yousefi et al., 2014). Songs are beneficial in teaching vocabulary, rhythm, sentence structure, and pronunciation of speech sounds (Richards, 1969, as cited in Davis & Fan, 2016). Pavia et al. (2019) proposed that this may be due to the rhythmical arrangement of language in songs, which consequently leads to deeper processing and better retention of vocabulary. Furthermore, the genre of popular songs has repetitive and conversation-like attributes, all of which are the cause of the “song-stuck-in-my-head phenomenon”, making them potentially useful in language learning (Murphey, 1990, as cited in Pavia et al., 2019).

On top of that, it was also found that individuals have the tendency to listen to the same song more than once (Pavia et al., 2019), in other words, repetitive listening. A study by Pavia et al. (2019) on Thai students showed that repeated listening to songs contributes to several vocabulary knowledge dimensions, namely spoken-form recognition, form-meaning connection, and collocation recognition.

Studies by Yousefi et. al (2014), Feng and Webb (2020), and Pavia et al. (2019) show that listening to songs is associated with incidental vocabulary learning. On a similar note, a study by Ahmad (2012) conducted on Saudi English as a Second Language (ESL) learners

showed that learners perform better in incidental vocabulary learning than intentional in terms of performance and retention; this is because students are put through the process of uncovering the meaning of unknown vocabulary using the known vocabulary as clues.

Problem Statement

Some studies suggest that listening to songs positively impacts vocabulary learning and is associated with incidental learning (Yousefi et al., 2014; Feng & Webb, 2020; Pavia et al., 2019). Even so, the listening skill is underemphasised in language learning (Arndt, 2020).

Previous studies on aural input showed that it was less efficient for vocabulary learning as compared to writing and reading; this may be due to aural input requiring faster processing in individuals; thus, listeners need to have acquired a certain level of understanding of input for learning to occur (Feng & Webb, 2020). However, a research done on a group of university students in China suggested that there is no significant difference between reading, listening, and viewing in terms of vocabulary gains and retention after a week of its encounter (Feng &

Webb, 2020). In addition, a study by Yousefi et al. (2014) on learning vocabulary with songs showed that songs affect long-term vocabulary retention positively compared to non-song materials.

Vocabulary acquisition is one of the main components in language learning and crucial to improve one’s language proficiency (Shakerian et al., 2016). Karami, and Bowles (2019) suggest that the importance of vocabulary is unparalleled as it is needed for

communication. Fortunately, past studies on songs and vocabulary suggest that listening to songs increase vocabulary proficiency (Pavia e al., 2019). In Malaysia, English is regarded as a second language (ESL); it is not uncommon for Malaysians to resort the colloquial form of Malaysian English by borrowing words from other languages when they lack vocabulary to express themselves in English. It is unclear how listening to English songs and the repetition of these songs will impact the vocabulary gains of ESL undergraduates outside of classrooms

as past studies such as ones by Pavia et al. (2019) and Feng and Webb (2020) were conducted within classrooms and in countries where English is treated as a foreign language. Therefore, this study will investigate perception of UTAR undergraduates towards listening to English songs. It will also examine the effect of the repetition of songs on the long-term retention of vocabulary gains.

Research Objectives

1. To examine the perception of UTAR undergraduates towards listening to English songs.

1. To investigate the effect of repetition of songs on long-term vocabulary retention gains.

Research Questions

1. What is the perception of UTAR undergraduates towards listening to English songs?

2. How does the repetition of songs affect the long-term retention of vocabulary gains?

Operational Definitions

In order to provide a more standardised comprehension for the research topic and to avoid disparities, the terminologies adopted in this study are defined as follow:

1. Long-term retention: Kahana (2014) referred to long-term memory as the system where information that is retained for days, months, years, or even beyond decades.

An article by Kohn (2014) suggested that an average of 90% of newly acquired information is forgotten within a week due to the forgetting curve. And so, this research will refer to long-term retention as information that is retained for a week.

2. Short term retention: Radvansky (2017) referred to short-term memory as a system where information is retained and processed temporarily, and can decay easily with distraction. Kohn (2014) proposed that within an hour of acquiring new information,

an average of 50% of it is forgotten. That said, this research will regard short-term retention as information retained within 10 minutes of acquiring new information.

Conclusion

This chapter covered the background of this research, the problem statements, the research objectives and research questions, as well as the operational definitions of the research. The following chapter will discuss the past literatures of the studies conducted in this field.

Literature Review

This chapter of the study will discuss and draw relationships between several issues related to the effects of repetitive listening of songs on vocabulary learning by looking at literature and past studies. The following sections will look at vocabulary learning for non- native English learners, songs in language learning classrooms, songs and vocabulary gains, memory in language learning, repetition and retention, repetition and vocabulary learning, and incidental vocabulary learning and memory.

Vocabulary Learning for Non-native English Learners

Learning a new language and reaching a certain level of proficiency requires a learner to effectively assimilate the four skills—listening, speaking, reading, and writing—together with grammar, vocabulary, spelling and pronunciation (Kuśnierek, 2016; Shakerian et al., 2016). The sub skill, vocabulary, is deemed one of the most important yet difficult aspect of a language (Karami & Bowles, 2019). There are about 100,000 word families in the English language, an average educated native English speaker only knows about 15,000 to 20,000 word families (Sagar-Fenton & McNeill, 2018). However, one must be aware that different skills require different amounts of vocabulary knowledge. Nation (2012) proposed that around 8,000 word families are required for one to deal with various unsimplified spoken and written texts. According to Sagar-Fenton & McNeill (2018), understanding audiovisual materials like TV shows and movies would require lesser than the aforementioned--3,000 of the most frequent word families; this is followed by conversing in the language, which would require the least amount of the most frequent word families, that is 800 to 1,000.

Additionally, a study by Miralpeix and Muñoz (2018) analysing the relationship between receptive vocabulary size and English proficiency of English as a Foreign Language (EFL) learners demonstrated a sizeable impact on the proficiency and performance in the four language skills of learners, particularly upper-intermediate and advanced learners. That being

said, many language learners in traditional learning struggle to get past the 2,000 to 3,000 word range despite their many years of study (Sagar-Fenton & McNeill, 2018). As a

consequence, learners might be demotivated from the inability to learn vocabulary efficiently, which may possibly lead to the abandonment of the targeted language (Karami, 2019, as cited in Karami & Bowles, 2019).

Over the years, studies have been conducted to determine the effectiveness, favourability, and helpfulness of various vocabulary learning strategies towards English learners; some of the researched strategies include determination strategies, social strategies, memory strategies, cognitive strategies, and metacognitive strategies (Çelik & Toptaş, 2010;

Mizumoto & Takeuchi, 2009). A study by Çelik and Toptaş (2010) conducted on Turkish EFL university students of elementary, pre-intermediate, and intermediate English levels revealed that intermediate learners found vocabulary learning strategies more useful in comparison to learners of elementary and pre-intermediate. Pre-intermediate learners came second highest in ratings for the usefulness of vocabulary learning strategies. Besides that, the results showed that learners found metacognitive strategies most useful with social strategies as the least useful. The learners also stated that cognitive and metacognitive strategies were useful and effective but they do not use them. On the other hand, they perceive determination strategies and social strategies as less helpful, but still employ these strategies These findings ultimately led to the conclusion that language learners rarely use vocabulary learning strategies and do not perceive the strategies as useful. The study suggested that since learners find some of the strategies as useful yet not employ them indicates a need for language learning programmes to be revised. Additionally, it is believed that the study would bring attention to the individual differences among EFL learners thus helping the educational sector be more aware of their roles in language learning and teaching,

which consequently would enable them to develop more suitable materials and activities for vocabulary learning other than encouraging learners to be more independent.

Another study conducted by Ghalebi, Sadighi and Bagheri (2020) compared the vocabulary learning strategies of Iranian EFL learners undertaking bachelor’s and postgraduate (master’s and doctoral) degrees in English Language studies. The findings revealed that learners of different academic degrees employ different learning strategies.

Metacognitive strategies appeared to be the most popular learning strategy employed by postgraduate students, which include activities like using notebooks for vocabulary, self- reflection questions, keeping learning journals, and self-testing vocabulary. Cognitive strategies like underlining and highlighting words, systemic repetition, and deducing word meanings from context came second in most frequent learning strategies employed by postgraduates. This is followed by social strategies, whereby postgraduates ask teachers to provide a synonym of the new word, ask teachers to provide a sample sentence using the new word, inquire meaning from classmates, converse with native speakers, and through group activities centred around word learning. On the other hand, determination strategies were the most commonly employed vocabulary learning strategy among undergraduate EFL learners, activities such as analysing speech parts, analysing word parts, and utilising bilingual and target language’s dictionaries. Memory strategies were the third most preferred vocabulary learning strategy among undergraduates, this includes activities like relating words to personal experiences, linking words with their synonymous and antonymous counterparts, drawing semantic maps, and so on. This confirmed the study’s hypothesis of learners of different academic degree levels having different vocabulary learning strategy preferences.

The researchers then suggested that learners need to be taught how to effectively use learning strategies to allow language learning to be properly facilitated within and outside of

classrooms.

The above findings suggest that while vocabulary is evidently a crucial component in the mastery of the four language skills, language learners struggle with efficient English vocabulary learning, which as a result hinder their language learning process and potentially deter them from the language itself.

Songs in Language Learning Classrooms

Songs are the combination of speech and music (Britannica, 2014). Since the lyrics of songs are essentially strings of vocabulary, listening to songs can provide listeners a great amount of language input (Schwarz, 2013, as cited in Pavia et al., 2019). Even though the listening skills remains underemphasised in language learning to this very day (Arndt, 2020), there is a long history in recommendation of usage of songs in foreign language classrooms (Davis & Fan, 2016). The lyrics of songs have the same characteristics that of oral stories, the only difference is that songs are produced in a musical manner rather than spoken (Yousefi et al., 2014). Krashen’s input of hypotheses suggested that the acquisition of vocabulary occurs when learners have a clearer understanding of its meaning; as such, the usage of actions, photos, and realia as linguistic aids would assist ESL learners in comprehending unfamiliar vocabulary (Yousefi et al., 2016). Studies conducted in Iran on junior high learners (Yousefi, 2014), in Indonesia on middle school learners (Gushendra, 2017), in China on learners aged 4 to 5 years old (Davis & Fan, 2016), in Thailand on learners aged 10 to 11 years old (Pavia et al., 2019), and in Poland on learners aged 11 to 12 years old (Kuśnierek, 2016) and adult Iranian learners aged 20 to 32 years old (Shakerian et al., 2016), all demonstrate findings that suggest the efficiency of song usage in increasing learners’ vocabulary proficiency in

language learning classrooms.

Kuśnierek (2016) conducted a study on the role of music and songs in teaching English vocabulary to Polish students, the results of the preliminary questionnaire showed that more than half of the young learners have music as one of their hobbies. When asked if

they have ever participated in English lessons that incorporate songs, most students answered yes but not frequently, followed by yes frequently, and no being the least popular answer.

Additionally, most think that learning vocabulary by listening to songs is a good idea and with “rather yes” being the second highest response and no being the least. In the same study, more than half of the students found the use of songs in lessons interesting. That said, songs are favoured by learners and teachers for several reasons. Firstly, they help learners relax;

most of the learners in Kuśnierek’s (2016) study admitted that listening to songs help them to relax with “it is hard to say” being the second most popular answer and no being the least.

According to Eken (1996, as cited in Piri, 2018), many educators authenticate the effectiveness of songs as a tool for relaxation, as a warmup activity, and even as a

background while other activities are being carried out in classrooms. Songs have also been shown to reduce the anxiety levels of learners in high-anxiety foreign language classrooms (Dolean, 2016, as cited in Pavia et al., 2019). This is highly beneficial in a classroom because foreign language classroom anxiety may lead to frustration, truancy, and throwing fits; all of which may hinder the language learning process of learners (Horwitz et al., 1986, as cited in Pavia et al., 2019). Based on these studies, it can be said that songs serve as effective

teaching tools in language learning classrooms, whilst proving learners a low anxiety environment.

Secondly, songs have recitable qualities; Shen (2009) suggested that song lyrics can be characterised according to their use of tune, rhythm, conversational speech, and poetic expressions. Consequently, these characteristics intrigue the learners, allowing them to retain the lyrics and recite them in the future. A study conducted by Bona (2017) on Business English students in an Indonesian university provided insight on the song genre preference of young adults; the results showed that a majority of the students prefer the pop genre

compared to other genres like alternative rock, dance, and hip-hop. A corpus-driven study

conducted by Murphey (1990, as cited in Pavia et al., 2019) suggested that the song genre pop is repetitive and similar to human conversations; additionally, there is also a “song stuck in my head phenomenon” which causes individuals to uncontrollably repeat a song in their head.

Nevertheless, the findings from literature and past studies in relation to songs in language learning classrooms can be summarised to as follows: language learners favour the usage of songs in learning, the effectiveness of songs in language learning classrooms are authenticated by educators, and the characteristics of songs are advantageous towards language learning.

Songs and Vocabulary Gains

Piri (2018) investigated the role of music in second language learning by putting Iranian undergraduate students aged 20 to 23 into three groups: all-music group, half-music group, and no-music group; learners in the all-music group are taught exclusively with songs as materials, half-music group learners are taught with song half the time, and no-music group learners are taught with no songs at all. The results revealed that the all-music group outperformed the other two groups with higher vocabulary achievement scores while the no- music group performed better than the half-music group. Interestingly, Medina (1993) also conducted a study on the effects of music on second language vocabulary acquisition showed that there were insignificant differences between the usage of music as a medium and

illustrations as linguistic support in terms of statistics. In this study, the learners were given four types of treatments: listening to a story spoken with illustrations, listening to a story spoken without illustrations, listening to a story sung with illustrations, and listening to a story sung without illustrations. Nonetheless, the treatments where learners listened to a story sung with illustrations and the story sung without illustrations both had descriptive statistics

exhibited higher learning gains compared to learners who listened to the story spoken without illustrations.

Davis and Fan (2016) conducted a study on vocabulary acquisition of Chinese kindergarten students through listening to songs. In the study, learners aged between 4 and 5 years old were put through 15 40-minute lessons over the course of seven weeks, which averaged to one to three classes per week; the learners sang the same warm-up song at the beginning of every class and spent the majority of each class learning and singing songs. A pre-test was conducted prior to the intervention and a post-test was conducted immediately after the intervention; the post-test results revealed that the usage of songs as a teaching method in a language learning classroom demonstrated no substantial difference compared to other methods such as choral repetition in terms of language acquisition.

Similarly, Feng and Webb (2020) analysed the most effective mode of input, particularly reading, listening, and viewing, for vocabulary learning among Chinese university students aged 19 to 21 years old. The results showed that significant vocabulary learning occurred on the learners through all three modes. Additionally, it demonstrated that written, audio, and audio-visual input are equally effective for incidental vocabulary learning, contrasting previous studies that suggest reading being more effective for vocabulary learning compared to listening. However, the study also suggested that there is little significance between the frequency of word encounters and incidental learning across the three modes, which once again, contrasts previous studies which suggest that the increase in encounters with a word in a written text increases the likeliness of the word being learnt. The possible reasons for the inconsistencies in the research findings across the experimental groups were addressed. First, the group that viewed the movie transcript was addressed, the material used in the study was a text initially designed to be presented as audio with visual support, making it not as appropriate to be used solely as reading material. The study suggests that the absence

of audio support may potentially have led to participants being less immersed in the material and paying less attention to unfamiliar words. The listening group was then addressed, the researchers stated that there was no clear relationship between the frequency of word occurrence and listening, whereby they proceeded to suggest that salience and relevance carried more importance in non-reading input as it would provide learners more context around the words and notice the words similar to that of ones in their L1, thus enabling them to guess the meaning of the words.

Past studies and literature pertaining to songs and vocabulary gains indicate that the usage of songs benefit not only young children (Davis & Fan, 2016), but also university students (Piri, 2018; Feng & Web, 2020) of EFL nations. That being said, it is clear that the usage of songs is effective in vocabulary learning for young and adult language learners.

Memory in Language Learning

Corballis (2019) suggested that language cannot exist without memory; all types of memories are crucial to language. Rowe (2021) stated that memories are formed when the brain processes the experiences when one consciously focuses on a task or subconsciously associates one information with another. Subsequently, memories can be categorised according to how long they are retained: sensory memories that are lost within a second, short-term memories that last less than a minute, working memories that lasts ranging from seconds to hours, long-term memories that lasts from hours to months, and long-lasting memories that can last from months to an entire lifetime. Similarly, Cowan (2008) described short-term memory as a limited amount of information that is temporarily at an easily accessible state, working memory as one that involves short-term memory and various processing mechanisms, and long-term memory as a vast storage that contains information and past experiences.

Regardless, Terada (2017) states that the human brain is wired to forget; in

consequence, learners often fail to retain the materials memorised and taught in class. A study by Richards and Frankland (2017) analysed the link between remembering (persistence) and forgetting (transience); they proposed that the underlying cause of individuals forgetting crucial information is due to the end goal of memory being optimised decision-making rather than transmitting information through time. In other words, this view suggests that learners forget the materials learnt in class because the brain deems it as unnecessary towards the survival of the species.

In short, studies and literature pertaining to memory and language learning suggest that knowledge and information of language learnt are inevitably forgotten due to how the human brain is wired (Terada, 2017; Frankland, 2017).

Repetition and Retention

When learners acquire new information, synaptic connections are formed; in order for the information to be retained, more synaptic connections need to be formed to widen the neural connections—a network that is often compared to a spiderweb—other than repeatedly accessing the memory of the information through time (Terada, 2017). The forgetting curve was proposed by Ebbinghaus in the 1880s, it measures how humans forget memories through time; the same research unveiled that information is rapidly forgotten when there is an

absence of reinforcements or connections, with 56% of the information being forgotten at about in an hour, 66% after a day, and 75% after six days (Terada, 2017). Nonetheless, Terada (2017) suggested five teaching strategies to be used in classrooms for teachers to assist learners in retaining newly learnt knowledge: peer-to-peer explanations, the spacing effect, frequent practice tests, interleaving concepts, and combining texts with images. In peer-to-peer explanations, learners reiterate the information learnt to peers, allowing the memory to be reactivated and robust. The spacing effect allows learners to review learnt

materials multiple times over a period of time through homework or lessons. Frequent practice tests are similar to the aforementioned, the difference is that it utilises activities like quizzes and tests to improve long-term retention and reduce stress, which is one of the factors reducing memory performance. The interleave concept alternates between two or more related concepts rather than focusing on one, this is a particularly useful strategy to teach concepts that students find confusing. The final strategy, combining text with images presents information to learners with the aid of visuals, facilitating their organisation of information.

Out of the five teaching strategies, three strategies emphasise the repetition of information;

these strategies are peer-to-peer explanation, the spacing effect, and frequent practice tests.

In short, past studies and literature in relation to repetition and retention suggest that information need to be repeated to prevent the information from decaying and gradually being forgotten due to the Ebbinghaus curve taking place (Terada, 2017).

Repetition and Vocabulary Learning

Horst et al. (2006, as cited in Horst, 2013) refer to a word that is encountered for the first time in a word learning situation as a “novel word”. Horst (2013) claims that a single encounter with a word rarely provides a learner with enough experience to support robust word learning. However, repeated encounters with a word would provide learners additional opportunities to store relevant knowledge from said experience, thus allowing a more robust word learning to be facilitated. Additionally, the word will eventually grow more familiar to the learner as more statistical regularities of the word’s usage are learnt along the way. In due course, the learner would be able to recognise the word’s referent despite the difference in contexts and delays, and ultimately, produce the word by themselves, in which the former novel word then becomes a “known word”. This situation of word learning via repeated encounters with gradually increasing degrees of familiarity is known as contextual repetition.

Horst also describes the term “word learning” as the act of learning about a word, including

its meaning, phonetic properties, and so on, such that it forms a robust representation in the learner’s vocabulary. A study by Penno et al. (2002, as cited in Pavia et al., 2019)

investigated the effects of repeated listening to the same story; the findings showed that one exposure was sufficient for learners to exhibit some knowledge of the target vocabulary items, and with the increase of the number of times the story was told, the learners knowledge of the target vocabulary items increased with their usage of the items getting more accurate whilst reiterating the story.

Similarly, Pavia et al. (2019) conducted a study that examined incidental vocabulary gains through listening to songs. Learners were divided into four groups, three experimental groups and a control group. The three experimental groups were exposed to a varied number of times the songs were played: one group listened to the songs one time, another group listened to the songs three times, and the last group listened to the song five times; the experimental group that listened to the songs five times performed substantially better than the other two experimental groups and the control group in the post-test, which suggests that repetitive listening of songs positively affect vocabulary gains, particularly spoken-form recognition.

Past studies and literature on repetition and vocabulary learning demonstrate that repeated encounters with initially new vocabulary allow learners to efficiently retain the words and acquire vocabulary gains (Horst, 2013). Subsequently, incidental learning that occurs when listening to songs also contribute to vocabulary gains (Pavia et al., 2019).

Incidental Vocabulary Learning and Memory

As discussed in previous sections, songs are linked to incidental learning of vocabulary learning and better retention of vocabulary knowledge. Richards and Schmidt (2002, Ahmad, 2012) regard incidental learning as “the process of learning something without the intention of doing so” or learning another thing when the purpose is to learn

something else. Ahmad (2012) suggested that incidental vocabulary learning promotes deeper mental processing and better retention as the learners’ ability to infer the meaning of words is honed; this is because when learners encounter new words in systematically arranged

materials, the words surrounding the new word provide the learners context, enabling them to infer the meaning of the word through the cognitive process of repeatedly thinking of the word thus effectively acquiring new vocabulary that is retained for longer period of time. A study conducted by Ahmad (2012) compared the effectiveness of intentional and incidental vocabulary learning and their effects on comprehension, retention, and application of new vocabulary. The study demonstrated that ESL learners who were treated with the incidental vocabulary learning technique performed significantly better statistically than those who were treated with the intentional vocabulary technique. This led to the researchers drawing the conclusion that learning new words through context is highly effective in vocabulary learning.

While this study was based on visual input, that is reading, the findings still are of importance as it demonstrates the link between songs, incidental learning, and better retention and application of vocabulary.

Conclusion

Overall, relevant existing literature and past studies were reviewed to clarify and connect the dots between several issues related to this research study, namely vocabulary learning for non-native English learners, songs in language learning classrooms, songs and vocabulary gains, memory in language learning, repetition and retention, repetition and vocabulary learning, and incidental vocabulary learning and memory. The usage of songs facilitates incidental learning and is beneficial to vocabulary learning as it allows learners to repeatedly think of the word. As mentioned, due to the Ebbinghaus forgetting curve and the nature of the human brain, the decaying of information over time is inevitable, but contextual

repetition, such is repeatedly listening to the same song, increases vocabulary proficiency.

Past studies such as ones by Yousefi (2014) and Shakerian et al. (2014) in Iran, Gushendra (2017) in Indonesia, Pavia et al. (2019) in Thailand, and Feng and Webb (2020) in China were conducted within classrooms and in countries where English is treated as a foreign language. Thus, the impact of English songs on the vocabulary gains of undergraduates in outside-of-classroom and English as a second language context like Malaysia remain unclear.

Methodology

This chapter covered the theoretical framework of the research, its participants, materials, instruments, the pilot test conducted prior to the actual study, the procedure, the data collection and analysis technique used, and as well as the study’s conceptual framework.

Theoretical Framework

The theoretical framework focuses on Krashen’s Input Hypothesis, contextual repetition, and the Ebbinghaus forgetting curve. Krashen’s input hypothesis suggests that vocabulary acquisition occurs in situations where learners have a better understanding of its context whereby learners start by understanding the input of it followed by attempting to produce it (Yousefi, et al., 2014). However, the human memory forgets information because memory deteriorates with the passing of time, with it declining at a faster rate in the initial stage and a slower rate at the following stage (Tamm, 2021). Repeated encounters of the same item or situation, that is contextual repetition, would enable robust word learning, which eventually familiarises it to a known word (Horst et al., 2013).

To illustrate, when songs are heard by learners for the first time, the words surrounding the new word provide them with some context of how the word is used.

Subsequently, when inferences of the word meaning are being made, the brain undergoes a cognitive process of repeatedly thinking of the word (Ahmad et al., 2012). However, if the representation of the word in the learner’s memory is not robust enough, the Ebbinghaus memory curve (Tamm, 2021) suggest that it would get forgotten over time. That being said, repeatedly playing the same song would repeat words to learners and provide more

opportunities for information related to the word to be stored (Horst et al., 2013); when combined with the repetitive thinking that occurs when learners make inferences of the new word’s meaning (Yousefi et al., 2014), this would result in better retention of newly acquired vocabulary.

Participants

The subjects of the study were 100 English language and English education

undergraduates of Universiti Tunku Abdul Rahman (UTAR). All of the participants identified as a student of Universiti Tunku Abdul Rahman (UTAR) Kampar Campus, Malaysia. Data collection for the preliminary questionnaire was conducted online via Google form over a period of two weeks. The convenience and snowball sampling methods were selected to be implemented in this study due to the participants having to meet the following set of criteria:

(i) student of English language or English education undergraduate programmes at Universiti Tunku Abdul Rahman (UTAR) Kampar Campus, Malaysia (ii) have never heard of the songs Across the Universe and Fool’s Gold, and (iii) score at least 86.67% for the 3,000 word level in the Vocabulary Levels Test

(VLT)

This snowball sampling method required participants to fill in a preliminary survey via Google forms and allow participants who have been identified to meet the criteria to further recruit legible participants.

The current study was conducted in an ESL context because English serves as a second language in Malaysia (Hashim, 2020); consequently, one’s residence in a country that has English as a first language would allow them full immersion in an English-speaking environment thus improving their English skills, particularly listening and speaking (Nutt, 2009). Regardless, the residence and nationality of participants were not limited as the VLT determines the participants’ level of proficiency in English vocabulary.

The students of the English Language and English Education undergraduate

programme at Universiti Tunku Abdul Rahman (UTAR) Kampar Campus were selected. This is because the study was carried out within the department of the researcher’s home

university, which comprises the English language and English undergraduate programmes (Univerisiti Tunku Abdul Rahman, n.d.).

A sample size of 100 participants was chosen, Bullen (n,d,) suggested that a sample size of 100 is required to have meaningful data with the prerequisite that the population does not exceed 1000. While the exact figure of the population size in the UTAR Kampar

Campus’s languages and linguistics department was unclear as it was not stated on the university’s faculty’s website, it was assumed that the size does not exceed 1000.

The English language and English education undergraduate programmes of UTAR require those who enrol to achieve a minimum of band 4 in MUET (Universiti Tunku Abdul Rahman, n.d.). The Malaysian Examinations Council (2014) states that MUET candidates who achieve a band 4 are regarded as “satisfactory users” of the English language and have

“satisfactory ability to function in the language” in terms of task performance. A study correlating MUET to International English Language Test (IELTS) showed that a band 4 grade is equivalent to a B2 in the Common European Framework (CEFR; Bidin et al., 2019), whereby they are expected to have a vocabulary size of 3250 to 3750 (de Souza & Soares- Silva, 2015). However, despite the Malaysian Examinations Council’s many attempts to revamp and reformat the test, some claim that the grading is inconsistent across the three sessions held throughout the year and that students graded differently (Arif, 2014; Azimilah, 2014; The Star, 2009; Shuryo, 2014). That being so, a Vocabulary Learning Test was

administered (VLT; Webb et al., 2017) in the preliminary questionnaire to ensure the consistency of the participants’ vocabulary proficiency. Only participants who got a

minimum of 26 out of 30 questions (86.67%) correct for the 3,000 word level were selected for the study, Webb et al. (2017) having a minimum of 26 out of 30 correct in a word level demonstrated that one has sufficient knowledge to move on to a higher word level as the song material were of higher word level. Consequently, participants who got more than 26

questions correct for the 5,000 word level was also excluded from the study because it is the highest word level in the VLT, and it would indicate that the individual likely has high English vocabulary proficiency.

Furthermore, it was important for the participants to have never heard of the songs

“Across the Universe” and “Fool’s Gold” as the unfamiliarity would enhance the validity of the study by ensuring that the learning gains were from the learning conditions (Nation and Webb, 2011, as cited in Pavia et al., 2019).

Materials

Two English songs were selected as research materials for the study. The song

“Across The Universe” by The Beatles (1969) was selected as song A while “Fool’s Gold”

by One Direction (2014) was selected as song B. Pavia et. al (2019) suggested that the songs need to be age-appropriate and interesting to motivate learners and facilitate incidental vocabulary learning. Therefore, songs from two pop songs from two popular boybands were selected. Based on the preliminary questionnaire given prior to this part of the study,

participants were confirmed to be unfamiliar with the songs. Additionally, Pavia et al. (2019) suggested that the song lyrics should consist of sufficient single-word items that were likely unknown to the participants. Subsequently, Nation (2007, as cited in Pavia et al., 2019) suggested that learning materials should consist of 95% of vocabulary that the learners have previous knowledge of to foster optimum learning.

The lyrics of the songs were retrieved from a music data website, Musixmatch, and examined to ensure that there were no discrepancies between the texts and songs. The lyrics were saved in text forms and analysed using vocabulary analysis programs Range for Texts (Cobb, 2020) and VP-Compleat (Cobb, 2021), both of which use 25,000 British National Corpus/Corpus Contemporary American English (BNC/COCA) word family lists to

determine the frequency of each word, and the coverage percentage of most frequent word families, which as a result indicate the difficulty of the selected song.

Song A

The song Across The Universe sings about putting the past behind oneself and embracing the arrival of a new year and better days. The song is 3 minutes and 48 seconds.

The lyrics consist of 80 different words and adds up to a total of 205 words.

The analysis of song A showed that participants need to know at least the most frequent 33,000 word families to be able to understand 94.780% of the song. It is worth noting that the lyrics contain several loan words: “jai”, “guru”, “deva”, and “om” of Sanskrit origin (Oxford University Press, 2021a; Oxford University Press, 2021b; Oxford University Press, 2021c; Oxford University Press, 2021d). While these words can indeed be found in the English dictionary, they fall into the categories of most frequent 20,000, 7,000, 31,000, and 34,000 word families respectively. These Sanskrit loan words were listed as Indian English in the dictionary (Oxford University Press, 2021a; Oxford University Press, 2021b; Oxford University Press, 2021c; Oxford University Press, 2021d), thus making them not as applicable in the Malaysian context. As a result, these words were not considered in this study altogether. Subsequently, these words were excluded from the analysis of the lyrics, the results showed that participants need to know at least the most frequent 3,000 words to be able to comprehend 96% of the lyrics. Additionally, the song has 1 word each from the most frequent 4,000, 5,000, 6,000, and 8,000 word families, and 2 words from the 7,000 most frequent word families list.

Table 1

Lexical Frequency Profile of Song A

Level Families Types Tokens Cumulative token (%)

1 52 56 152 86.9

2 10 10 10 92.6

3 3 3 6 96

4 1 1 1 96.6

5 1 1 1 97.2

6 1 1 1 97.8

7 2 2 2 98.9

8 1 1 1 99.5

Off-list - 1 1 100

Song B

The song Fool’s Gold sings of the awareness of being used in a one-sided romantic relationship and willingness to remain in it. The song is 3 minutes and 30 seconds long. It has a total of 264 words in the lyrics with 79 different words.

The analysis of song B showed that learners would require 3,000 of the most frequent word families to comprehend 94.7% of the song. Previously, it was mentioned that the word level of the participants is required to be 95% of their word level for optimum learning to occur (Nation, 2007, as cited in Pavia et al., 2019), however, it is likely that learners will encounter more than 5% of words that are above their word level when listening to songs in their daily lives (Pavia et al., 2019), so this material that is 0.3% higher than their word level would still serve as valid listening material. Additionally, the song also has one word each the most frequent 5,000 and 6,000 word family list.

Table 2

Lexical Frequency Profile of Song B

Level Families Types Tokens Cumulative token (%)

1 58 67 236 89.4

2 6 6 11 93.6

3 1 1 3 94.7

4 1 1 1 95.1

5 1 1 1 95.5

6 1 1 1 95.9

Off-list - 2 11 100

Target Words

Ten words each from song A and song B were selected as target items. The frequency of the target words ranged from one to twelve. Nine of the target words from songs A and B were from word levels higher than the third level of most frequent 1,000 words from Nation’s BNC/COCA word family lists (2012), words below the 3,000 word level were also used to encourage participants to complete the test.

Table 3

Target Single-Word Items and Their Collocations Song Single-word

item Word

Level Frequency of exposure

(per play) Collocations

"Across The Universe"

change 1 12 (my) world

drifting 3 1 through (my)

opened mind

universe 3 4 across (the)

tumble 4 1 blindly

sorrow 5 1 pools of

caressing 6 1 me

meander 7 1 thoughts

inciting 7 1 and inviting me

slither 8 1 wildly

undying 1 1 love

"Fool's Gold" falling 1 6 for you

fool 1 6 ('s) gold

use 1 3 me

admit 1 1 (that) I’m

constant 3 1 star

calm 3 1 my mind

regret 3 3 I don't

distraction 4 1 you are a (shining)

reckless 5 1 I’m

crow 6 1 on a wire

Instruments

Three data collection tools were used throughout the study: a preliminary

questionnaire that includes demographic questions and a vocabulary levels test (see Appendix A), and two post-tests (see Appendix B; see Appendix C), that include an open-ended

question section (see Appendix D), all of which were conducted online.

Preliminary Questionnaire

The preliminary questionnaire is an untimed questionnaire hosted on Google forms.

This was to restrict the access of the questionnaire to only users in the Universiti Tunku Abdul Rahman organisation. It comprised two sections, section A and section B. Section A comprised questions regarding the demographic of the participants. Section B comprised questions adopted from a vocabulary levels test. These questions determined if the participants fit the criteria of the research subject.

Vocabulary Levels Test

The updated Vocabulary Levels Test (VLT; 2017) by Webb et al. (2017) that comprises a total of 50 questions was adopted and included in the final section of the

preliminary questionnaire. This untimed test was included in the preliminary questionnaire to select participants who score at least 86.67% for the 3,000 word level, but below 86.67% for the 4,000 and 5,000 word levels. The participants were presented with multiple-choice questions, they were asked to select the most suitable word for each of the meanings

provided. The option “I don’t know” was also included to prevent participants from randomly selecting an answer and ensuring the accuracy of the test. Additionally, participants were not allowed to edit the form upon submission to ensure the accuracy of the test.

Open-ended Questionnaire

The open-ended and untimed questionnaire was also hosted on Google forms to restrict the access of the questionnaire to only users in the Universiti Tunku Abdul Rahman organisation. The link to the questionnaire was emailed to participants who had answered the preliminary questionnaire and fulfilled the criteria, each student was limited to one response.

The questionnaire contained a total of 5 open-ended questions. All of the questions were centred around undergraduates’ perception of songs, their effect on vocabulary gains, and their effect on long-term vocabulary retention.

Multiple-choice Test

The post-tests were presented in the form of multiple-choice questions on Google forms. Once again, the test was hosted on Google forms and the access was limited to users within the UTAR organisation. There were two post-tests: post-test A was based on the word items from song A, and post-test B was based on the word items from song B. Both post-tests contained two sections and a total of 20 questions: form-meaning connection with 10

questions, and collocation recognition with 10 questions. Participants were given 5 minutes to answer each post-test, since Google form does not have a native timer, an extension was added to the form to limit the answering time of each form. Participants were also not

allowed to edit their answers upon the submission of their answers to ensure the accuracy of the test.

The form-meaning connection section presented the participants the target word with four options: (a) the meaning of the word, (b) the meaning of another word from the target word list, (c) the meaning of a word from the VLT, and (d) I don’t remember this word. The fourth option was present to reduce the effect of guessing that may skew the accuracy of the test.

The second section of the test examined the participants’ collocation recognition. The participants were presented the target word and four options: (a) the target word with the target collocation, (b) the target word with another word from the target word list (c) the target word with another word from the song, and (d) I don’t remember this word.

Pilot Test

A pilot test was conducted prior to the commencement of the actual study. This was done so to validate the practicality of the test items and procedure. 10 participants were involved in the pilot test, that is 10% of the actual study’s sample size. The participants involved in this pilot study were not included in the actual study to ensure the accuracy of the tests.

On October 23rd, 2021, 1200 hrs, the link to the preliminary questionnaire was emailed to students in the tutorial class of the subject UALL3033 Public Speaking and Oral Presentation. The students within this tutorial are all English language and English education students. By October 27th, 2021, evening, there were 10 participants who met the criteria of the study. The participants were randomly divided into two groups: long-term group and short-term group. An email was sent to the participants on 0800 hrs of October 28th, 2021, the participants were asked to fill in the open-ended questionnaire and informed of the tests that would take place on October 30th and November 13th.

The following week, October 30th, 2021, 1200 hrs, the participants were gathered in a group call on the online communication platform Microsoft Teams. Song A was played five times. The long-term group was dismissed and advised to not listen to the song prior to the post-test. The short-term group immediately answered the post-test and were given 5 minutes to complete the test. The session ended at 1225 hrs, with a duration of 25 minutes. The long- term group were told that a link would be sent to their emails in a week. On week two, November 6th, 2021, the long-term group answered the 5-minute timed post-test.

On week three, November 13th, 2021, 1200 hrs, the participants were gathered in a group call on the online communication platform Microsoft Teams once more. Song B was played once. The long-term group was dismissed and once again advised to not listen to the song prior to the post-test. The short-term group immediately answered the post-test and were given 5 minutes to complete the test. The session ended at 1210 hrs, with a duration of 10 minutes. The long-term group were told that a link would be sent to their emails in a week.

On week four, November 20th, 2021, the long-term group answered the 5-minute timed post- test.

After the sessions and post-test, the participants were contacted again through email for feedback. More than half of the participants reportedly had trouble staying committed to the research due to the excessive number of questionnaires. The participants suggested reducing the number of questions or number of tests altogether. One of the participants stated that many questions in the preliminary questionnaire initially deterred them and made them feel as if the questionnaire was “never-ending”. As a result, the two post-tests were combined into a single questionnaire and the tests were carried out back-to back to mimic real-life situations whereby people to different songs in one sitting. Additionally, the open-ended questions were moved from the preliminary questionnaire to the end of the post-test. This was done to reduce the number of questions in the preliminary questionnaire.

Procedure

The study employed a mixed-method research design, both qualitative and quantitative methodologies were used. The participants were told that the purpose of the study was to investigate the perception of Malaysian undergraduates on songs and the impact of songs on long-term memory. This was done to encourage participants to focus on the song materials rather than purposefully paying extra attention to the difficult or unfamiliar words song during the intervention. A week after all 100 of the participants have completed the preliminary questionnaire together with the VLT included within. On the same day, they were randomly assigned to two groups evenly: the short-term group, and the long-term group.

The short-term group were tested on short-term retention and sat for the post-test

immediately after listening to the songs, while the long-term group were tested on long-term retention and sat for a delayed post-test a week after listening to the songs. Each group consisted of 50 participants.

On the following week, both groups listened to song A five times, and song B one time. Song B was played right after the participants listened to song A to mimic real-life situations where people listen to various songs in one sitting. The short-term group

immediately completed the post-test right after listening to the two songs. As a preventative measure, the long-term group was advised to not listen to the songs after the intervention and before the delayed post-test, however, since it was impossible and unethical for the

researchers to monitor the listening habits of the participants outside of the study, it was explained to them that this was important because would lead to inaccurate results in the study. One week later, the long-term group completed the delayed post-test A.

Conceptual Framework

Figure 1 is an illustration of the present study’s conceptual framework.

Figure 1

Conceptual Framework

Data Collection and Analysis Technique

The data collection process started with the distribution of google form links to English Language and English Education programme students. A list containing the names of

undergraduates that major in English Language and English Education was acquired from the faculty of general office of the faculty of arts and social sciences UTAR. Then, the form links were sent on the Microsoft Teams platform to groups containing students from the

programme and also via private messaging. This was done to ensure that only students from the English Language programme and English Education programme would participate in the study, and to ensure the accuracy of the data collected. After enough participants had passed the VLT, these participants were randomly divided into two groups: short-term group and long-term group, and were once again asked to fill out Google form that served as their post- test. The data from said Google forms were compiled and directly sent to a spreadsheet on Google Sheets. The quantitative data was tabulated and analysed, while the quantitative data

was grouped according to themes and analysed. Google Sheets was used as the analysis technique due to its free interactive statistical analysis and data management, and it being linked directly to the Google form prevented human errors such as wrong input of data. Later, the quantitative was converted into charts and t-tests for easier viewing of data, and the two different types of t-tests—paired and independent—were conducted using the data to determine the significance of the findings.

Conclusion

This chapter covered the theoretical framework of the research, its participants, materials, instruments, the pilot test conducted prior to the actual study, the procedure, the data

collection and analysis technique used, and as well as the study’s conceptual framework. The following chapter will present and discuss the results attained from the study.

Results and Discussion

In this chapter, the findings of the study are highlighted. This chapter provides an analysis of the data collected in regard to the undergraduates’ perception of listening to English songs and the effects of repetition of songs on long-term retention of vocabulary gains.

Undergraduates’ Perception of English Song Listening

The qualitative data on the undergraduates’ perception of English song listening were gathered after conducting the quantitative post-test. The 100 responses were categorised according to their themes and will be discussed in the subheadings below. The following subheadings will demonstrate the data collected in an attempt to answer the first research question.

Tune and Rhythm

According to the participants, the favourable tune and rhythm of English songs appears to be one of the reasons undergraduates choose to listen to English songs. To quote one of the participants, “I think the melody is catchy”. Another participant stated that they

“prefer the tunes and melodies of English songs”, while another one of the participants claimed that “the rhythm is catchy”.

Based on these responses, it can be deduced that participants exhibit preference and favour towards the nature of English songs. Cutler (2003, as cited in Killingly, Lacherez and Meuter, 2021) described the English language as being associated with “high status and prestige, opportunities of becoming international artists, and to be ‘easier’ and to ‘sound better’”; that said, these associations lead to many artists pursuing a career in English music instead of other languages. Consequently, the market is flooded with predominantly English songs. Similarly, individuals may also listen to English songs due to the same reasons artists sing English songs, to be considered of high prestige. In addition to this, since all participants are either undergraduates under the English Language programme or the English Education

programme, many may feel familiar with the language and thus prefer listening to English songs

In regard to the participants finding English songs catchy, Jakubowski et al. (2017, as cited in Killingly, Lacherez & Meuter, 2021) stated that Western songs that are faster in tempo tend to elicit earworms, which is commonly known as the song-stuck-in-head phenomenon. Killingly et al. (2021) proposed that catchy songs compel listeners to sing along in their heads and aloud, and they may or may not be consciously aware of doing so;

these songs have a high possibility of being “stuck” in the individual’s head by lodging themselves in the individual’s working memory. Additionally, a study by Rahmania and Mandasari (2021) showed that listeners find themselves singing along to songs when they enjoy said songs; this research finding demonstrated that it was easier for participants to memorise the pronunciation, intonation, and rhythm of the song lyrics. On that note, one of the participants admitted that “singing along helps me develop new vocabulary”, indicating that the participant enjoys listening to music and finds themselves learning new vocabulary when singing the songs aloud.

To illustrate, the catchiness of an English song will make listeners consciously or unconsciously think of the song actively and sing along to it, causing it to be in their working memory. That said, the catchiness of English songs may aid in learning English vocabulary due to its nature of being repeatedly lodged in the listener’s memory.

English Pronunciation

Another one of the reasons undergraduates listen to English songs is that it increases their proficiency in English pronunciation. One of the participants admitted that they listen to English songs “to learn the pronunciation of English words”. Interestingly, the pronunciation of vocabulary in English songs is also one of the reasons some participants think that

listening to English songs is not a good idea for learning English vocabulary. To quote one of