To access detailed and updated licensing information, please visit https://doi.org/10.11647/. Updated digital materials and resources associated with this book are available at https://doi.org/10.11647/.

List of Boxes

It is sobering to think that there is a very real risk that our children will never have the opportunity to see gorillas, rhinos or elephants in the wild. For that reason, we make this textbook available for free under a Creative Commons (CC BY) license, to guarantee the rights of anyone to use and disseminate this work to anyone who wants to make a difference in the future of Africa's biodiversity and its people.

Scope

Satellite image of Africa, with the Sahara desert (sand-coloured) in the north and the Afrotropical ecoregion's tropical ecosystems (in green) further south prominently featured. The text does cover some areas not usually considered part of the Afrotropics, but which share several affinities with the Afrotropical region.

Taxonomy and the IUCN Red List categories

These additional areas include oceans within 200 nautical miles of sub-Saharan Africa, and oceanic islands in the Atlantic Ocean that are usually treated as part of the Palearctic realm, namely Cabo Verde, St. We preface this discussion by alerting readers that the threat status of each assessed species mentioned in the text is indicated by one of the seven acronyms listed below, immediately following its scientific name.

Organisation of the book

We are fully aware that the delay between taxonomic updates and IUCN assessment updates may give the impression that this textbook's taxonomy may sometimes be out of date. Note that the suggested readings are not meant to be absolute; indeed, they should be adapted to local contexts and curriculum requirements.

Bibliography

Each chapter concludes with an extensive bibliography that serves as a starting point for readers interested in specific conservation topics and for lecturers wishing to adapt the suggested bibliography. The textbook concludes with four appendices, which should encourage readers to take the activist spirit of this field to heart.

List of Acronyms

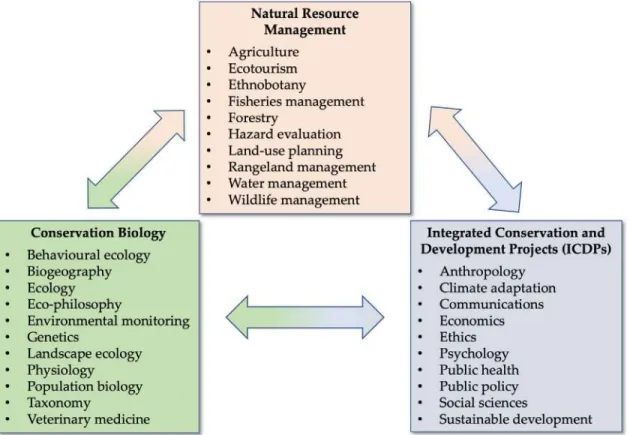

What is Conservation Biology?

- Conservation Biology is Still Evolving

- The Role of Conservation Biologists

- The Value of Scientific Methods

- Environmental Ethics

- Conservation biology’s ethical principles

- Summary

- Topics for Discussion

- Suggested Readings

One day, people will likely look back and say that this time - the first half of the 21st century - was an important and exciting time when people worked together and acted locally and globally to prevent extinction of many species and ecosystems. Most prominent among these is the Society for Conservation Biology (SCB, Figure 1.2), which is an international non-profit professional organization with a mission to advance "the science and practice of conserving Earth's biological diversity."

Introduction to Sub-Saharan Africa

- Sub-Saharan Africa’s Natural Environment

- History of Conservation in Sub-Saharan Africa

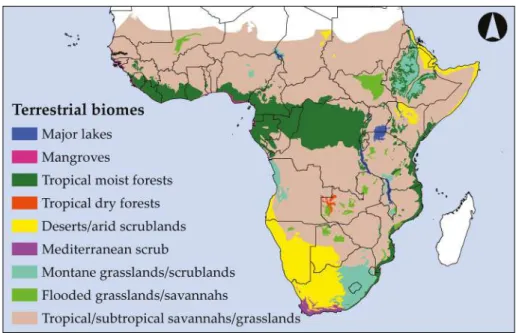

Prominent marine biomes include tropical coral reefs along Africa's east coast, as well as temperate continental shelves and seas off South Africa and Namibia (Spalding et al., 2007). For example, East Africa's naked mole rat (Heterocephalus glaber, LC) is the world's only mammalian thermoconformer—.

Sacred forests today

Resistance to human pressures

- The 1800s and launching of formal conservation efforts

- Conservation efforts after colonialism

- Conservation in Sub-Saharan Africa Today

- Ongoing Conservation Challenges

- Persistent poverty

- Obstructive mindsets

- Weak governance/institutional structures

Following concerns about declining wildlife populations, particularly in the southern tip of South Africa, Sub-Saharan Africa's first official environmental legislation was introduced in 1657, followed by the region's first official environmental law in 1684 (MacKenzie, 1997). Interest in formal protection of Africa's biodiversity began to intensify during the 19th century. The Cape Forest Act played an important role in the proclamation of the first officially protected areas of the Cape Colony, namely the Tsitsikamma and Knysna Forest Reserves, in 1888; today these lands are included in South Africa's Garden Route National Park (Figure 2.4).

The region's first game reserves were gazetted as early as 1889 in the DRC to protect elephants. Soon after, in 1903, Africa's first conservation non-governmental organization (NGO) was established, namely the Society for the Preservation of Wild Fauna of the Empire (known today as Fauna & Flora International or FFI). The following year, South Africa's Sabie Game Reserve (which was originally gazetted in 1898) was renamed and expanded into Kruger National Park.

As a result, many of Africa's first formally protected areas were established on land forcibly taken from communal ownership, and access to the 1933 Convention on the Conservation of Fauna and Flora in the Natural State (often referred to as the London Convention). For example, Shamwari Private Game Reserve, one of the more successful upper private protected areas (Figure 2.C), is adjacent to Addo Elephant National Park in the Eastern Cape.

Southern Africa’s principle transit hub for wildlife trafficking

International efforts to combat illegal wildlife trade—now the fourth largest transnational crime in the world (Nellemann et al., 2016)—have intensified in recent years, but Malawi has escaped public scrutiny due to its small size and relatively small wildlife numbers. Despite these factors, Malawi's wildlife populations have been decimated by poaching in the last few decades. For example, the Kasungu National Park's wildlife was so abundant in the 1980s that animals were moved to the Kruger National Park in South Africa.

Central to region’s poaching hotspots

With an estimated interception rate of 10%, the true scale of the ivory trade was clearly much larger than previously thought (Waterland et al., 2015).

Risk-reward ratio in favour of criminals

Turning the Tide

Remember, by comparison, no one convicted of a wildlife crime between 2010 and 2015 was locked up, and the average fine was just $40. Other initiatives included improving management of protected areas, establishing the nation's first wildlife crime investigation unit, and establishing an interagency wildlife crime committee to improve cooperation and information sharing. The Lilongwe Wildlife Trust is currently the only non-governmental organization sanctioned to prosecute wildlife crime cases in partnership with an African government.

Support from the very top

Focus on trafficking

What’s next for Malawi?

- Skills shortages

- Competing interests

- Conclusion

- Summary

- Topics for Discussion

- Suggested Readings

- What is Biodiversity?

- Species Diversity

- Genetic Diversity

Gorillas in the crossfire: population dynamics of the Virunga mountain gorillas over the past three decades. Preservation of colonial wildlife and the origins of the Society for the Preservation of the Wild Fauna of the Empire. Review of the protected area network in Guinea, West Africa and recommendations for new sites for biodiversity conservation.

Floristics of the Angiosperm Flora of Sub-Saharan Africa: An Analysis of the African Plant Checklist and Database. Effects of banning safari hunting tourism on rural livelihoods and wildlife conservation in Northern Botswana. Conservation of the Maiombe Forest, Cabinda, Angola, as part of a transboundary conservation initiative.

The potential for the designation of protected areas for conservation and for the identification of conservation corridors as part of the planning process of the Mayombe Forest Ecosystem Transboundary Conservation Area. The first part of the name, Panthera, identifies the generic epithet (or simply the genus); in this case, panthers or big cats.

Monitoring Species Using eDNA

Ecosystem Diversity

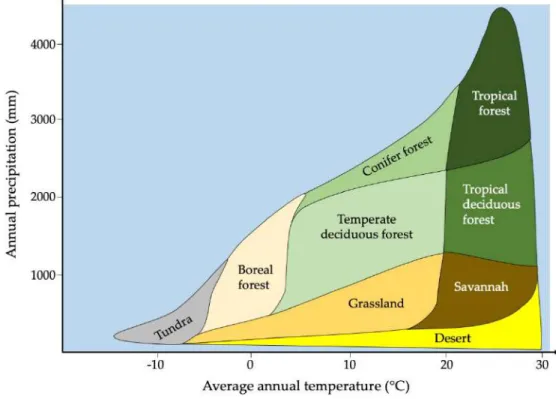

For example, water that evaporates from leaves, the soil, and other surfaces can later become rain or snow, providing drinking water that sustains life. For example, in a freshwater stream, the biological community present is largely determined by the physical characteristics of the stream, including water chemistry, temperature, flow rate, and substrate. For example, average temperature and rainfall determine which biome will dominate, which in turn influences which species will be present.

For example, the trees present in a forest ecosystem can affect wind speed, light, moisture, soil chemistry, and temperature. Likewise, marine biological communities, such as kelp forests, seagrass beds, and coral reefs, can affect water temperature, water chemistry, sunlight penetration, and wave energy. For example, a particular plant species can only grow in one type of soil, be pollinated by one type of insect, or have its seeds dispersed by only one type of animal.

For example, studies from Ivory Coast and Southern Africa have linked dung beetle population declines to the extinction of large herbivores such as elephants and buffalo (Nichols et al., 2009). Finally, after many decades, climax species representative of mature forests, such as birds that nest in the holes of dead trees, begin to colonize the area.

Patterns of Biodiversity

- Challenging species identifications

- Implications of challenging species identifications

- Measuring species diversity

- How many species exist?

- Where are most species found?

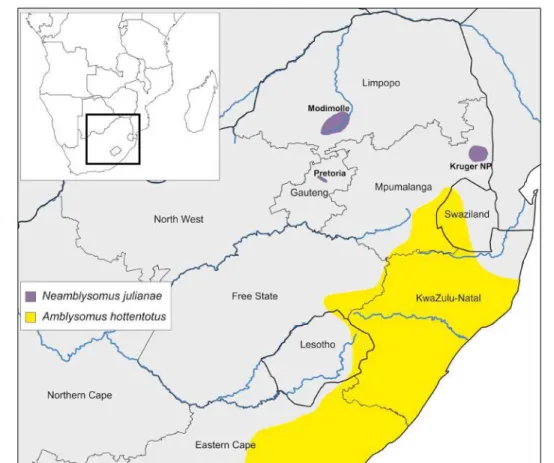

Unfortunately, the final number of giraffe species is still disputed due to the different assumptions made by each study and how that affects the number of species (Bercovitch et al., 2017). Such natural hybridization plays an important role in speciation (the evolution of new species); for example, it may have contributed to the great diversity of cichlid fish in the Rift Valley lakes of Africa (Salzburger et al., 2002). First, preliminary findings suggest that Hottentot's golden mole contains several morphologically similar, but evolutionarily distinct and genetically divergent lineages, some of which would represent undescribed cryptic species (Mynhardt et al., 2015; Taylor et al., 2018).

The utility of subspecies in conservation has long been the subject of controversy (Coetzer et al., 2015). The current abundance of the Kappa parrot is relatively low but stable, with an estimate of fewer than 1,600 birds in the wild (Downs et al., 2014). To date, taxonomists have described about 1.5 million species that share this planet with us (Costello et al., 2012).

For example, an amateur botanist recently discovered two new flowering plants in the heavily researched Cape floristic region (Bello et al., 2015). For example, advances in genetic research have recently highlighted that the African clawed frog (Xenopus laevis, LC)—a popular model organism in biomedical research—consists of seven distinct species (Evans et al., 2015).

Seychelles Oceanic

- Summary

- Topics for Discussion

- Suggested Readings

- Why Should We Protect Biodiversity?

- Material Contributions

- Regulating Services

- Nonmaterial Contributions

- The Long-Term View: Option Values

- Environmental Economics

- Summary

- Topics for Discussion

- Suggested Readings

- The Scramble for Space

- What is Habitat Loss?

- Drivers of Habitat Loss and Fragmentation

- Habitat Loss’ Impact on Africa’s Ecosystems

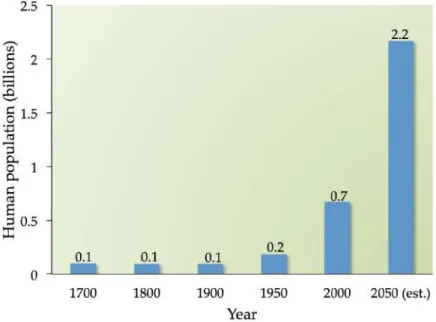

- Population Growth and Consumption?

- Concluding Remarks

- Summary

- Topics for Discussion

- Suggested Readings

- Our Warming World

- Drivers of Climate Change

Before the genocide, Rwanda had one of the highest human population densities in the world, putting a huge strain on its natural resources. Remnant populations of the pygmy hippopotamus ( Choeropsis liberiensis , EN) are found primarily within the transboundary rainforests of West Africa that include Côte d'Ivoire, Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone ( Ransom et al., 2015 ). At the time, this Ethiopian agreement threatened both the second largest mammal migration on Earth (Ykhanbai et al., 2014) and the livelihood of the local Anuak pastoralist community (Abbink, 2011).

Of the 126 species involved in this migration, over 40% have continuously declined in abundance since 1970 (Vickery et al., 2014). Illustrating this point, a drought in the Sahel, an important migratory stopover, led to food shortages that killed 77% of the world's common whitethroat (Sylvia communis, LC); even today, this population has yet to fully recover (Vickery et al., 2014). Wood extraction for commercial fish smoking is one of the major causes of mangrove loss, even within protected areas (Feka et al., 2009).

Two Ethiopian birds (Figure 5.D), the Liben's skylark (Heteromirafra archeri, CR) and white-winged flufftail (Sarothrura ayresi, CR), exemplify many of the dilemmas. Environmental Aspects of the Floodplain Developments of Africa (Leiden: Center for Environmental Studies, University of Leiden). National action plan for the conservation of the pygmy manatee in Liberia (Cambridge: FFI; Monrovia: FDA).

I: The State of the World's Land and Water Resources for Food and Agriculture (SOLAW)—Managing Systems at Risk (Rom: FAO; London: Earthscan).