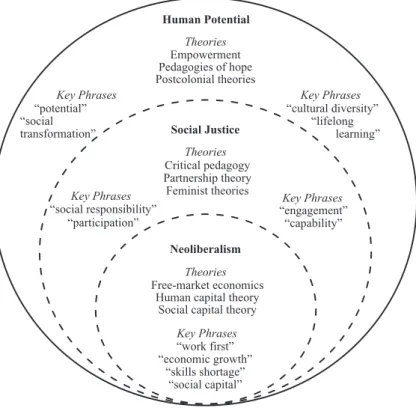

We have identified three common threads central to the connection between equity and the policy contexts of Indigenous higher education in Australia. There has been unprecedented growth in research focusing on student equality in higher education.

Conclusion

In addition to RAP, some universities have taken significant steps to integrate indigenous knowledge into the higher education curriculum (Behrendt et al. 2012). Other universities have taken steps to increase the cultural competence of their staff (Scott et al. 2013).

James Smith would like to thank the National Center for Student Equity in Higher Education for supporting a Visiting Fellowship throughout 2015 to conduct the research necessary to conceptualize and develop the content of this chapter. Unlocking the gates to the farmers: Are policies of "fairness" or inclusion more important to equity in higher education.

What Do We Know About Community Engagement in Indigenous Education

Introduction

Currently, little consideration is given to theoretical and practice implications associated with community engagement. This chapter aims to provide a descriptive account of the way community engagement is currently described, understood and applied in educational contexts in Australia.

What Do We Know About Indigenous Community Engagement?

Community engagement in an urban area will take a different form than engagement in a remote community. We suggest that the same general considerations could apply to the way Indigenous community engagement is approached, especially within educational institutions.

What Do We Know About Indigenous Community Engagement in Education Contexts?

Using A Share in the Future – Indigenous Education Strategy 2015–2024 as an example, 'engagement' has recently been identified as one of the five most important elements to improve Indigenous education outcomes in the Northern Territory (Northern Territory Department of Education 2015a). An 'engagement' goal outlined in the strategy is that 'parents and communities are engaged with the aim of supporting their children throughout their learning journey' (Northern Territory Department of Education, p. 9). These measures stand in stark contrast to the desired outcome outlined in the strategy, which focuses on consistent school attendance (which, incidentally, aligns with a parallel national policy investment known as the Distance Schooling Strategy).

What Do We Know About Community Engagement in Higher Education?

Interestingly, community involvement is now also used as a common assessment criterion in academic staff promotion processes in many Australian universities. In our experience, these are remarkably similar factors to negotiate in Indigenous community engagement work. One might assume that these dimensions are therefore more pronounced in Indigenous community engagement, which focuses on supporting pathways to higher education.

What Do We Know About Indigenous Community Engagement with Respect to Pathways into Higher

By developing deep relationships with elders and community members, the CAP-ED team designed a program with community ownership of both the process and outcomes (Fredericks et al. 2015, p. 61). The concepts that Fredericks et al. 2015) highlight important considerations when engaging Indigenous students and families in discussions about higher education. These are important lessons to consider when investing in Indigenous community engagement in higher education contexts.

What Are the Opportunities for Improved Indigenous Community Engagement in Indigenous Higher Education

We have identified a new evidence base on Indigenous community engagement in higher education in Australia. In this chapter, we have progressively examined the concept of community engagement in relation to (a) Indigenous community engagement; (b) Indigenous community engagement in education; (c) community engagement in higher education and (d) Indigenous community engagement in higher education. We then briefly discussed some of the opportunities to improve Indigenous community engagement in the higher education sector.

A Design and Evaluation Framework

University Sector Background

In 2010, Indigenous Australians accounted for only 1.4% of all university enrolments, but their numbers were 2.2% of the Australian working-age population (Behrendt et al. 2012). The Bradley (2008) review highlighted that the group of eight universities (Go8) appeared in the 'bottom percentile' of all Australian universities in enrolling students from low socio-economic status (LSES). Adelaide is a member of the Go8 alliance of Australia's largest and oldest research-intensive universities.

University Case Study Context

The reassignment of a senior Aboriginal academic to Dean of Indigenous Education resulted in the genesis of the University of Adelaide's Torres Strait Islander Integrated Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Education Strategy Tarrkarri Tirrka University of Adelaide 2013a). This innovative coalition reported directly to the strong leadership position of Deputy Vice-Chancellor Academic. The goals of greater diversity were reaffirmed in the University's new Strategic Plan known as the Beacon of Enlightenment University of Adelaide 2013c).

Definition and Framework for Analysis

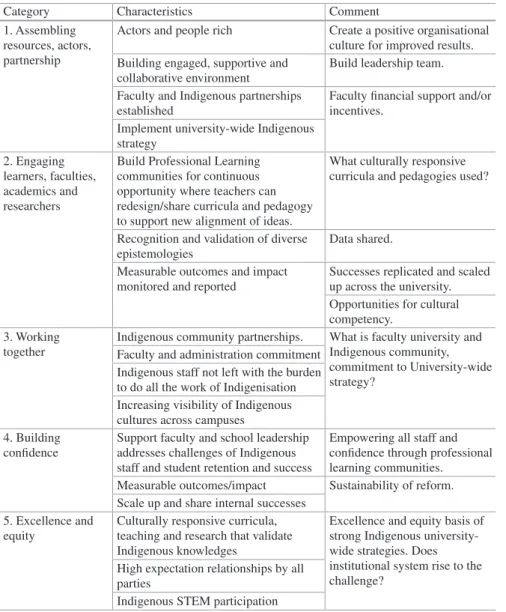

While Gale's matrix (Gale et al. 2010) provided a robust research and evaluation framework for this Adelaide case study, it required updating to strengthen its matrix to capture a richer set of specific themes that take into account the institutional culture of the University of Adelaide. Accordingly, Gale's matrix has been adapted and termed A Design and Evaluation Framework for Indigenization (DEFI) (Table 4.1). Support faculty and school leadership address the challenges of Native staff and student retention and success.

Results

The DEFI framework was used to develop broad themes and a set of questions to support the analysis. In 2014, all internal educational change efforts saw the number of Indigenous students exceed 200, the largest recorded cohort in the University of Adelaide's history. For the sake of brevity in this chapter, data on Indigenous staff and total student numbers are used to tell the story of educational change.

Assembling Resources, Actors and Partnerships

Led by the Dean of Indigenous Education, members included faculty representation, Indigenous staff and students, and the Indigenous Student Equity Unit. Strong community engagement was established through a Memorandum of Understanding established between the University and the local Kaurna Aboriginal Elders (Kaurna Warra Pintyanthi and Karrpanthi Aboriginal Corporations). Various long-standing and new university-wide Indigenous pilots engaged the community in partnership, including some areas of the university that were impervious to change.

Engaging Learners, Faculties, Academics and Researchers

An effective professional learning community was created to provide teachers with the conditions to redesign curriculum and pedagogy that focused on improving local student achievement. Professional learning community workshops introduced teachers to the Tirrka and University Beacon strategies and linked to international theory on improving Indigenous outcomes. Conceptual pedagogy theory, teaching techniques and research approaches used by experienced staff managing major studies were shared in professional learning community workshops.

Working Together

Practitioner enrollment in intercultural competence peaked in 2014 when 151 university staff members (target 30) participated in workshops, with feedback gathered to support the idea that such workshops improved staff confidence in Indigenous affairs. In addition, junior Indigenous staff lacked access to internal competitive faculty conference scholarships, which are critical to advancing their careers. The Taplin Indigenous Scholarship for International Education was established with philanthropic support to increase capacity to retain Indigenous staff (University of Adelaide, 2012c, 2013d).

Building Confidence

Hargreaves and Goodson's (2006, p. 5) empirical studies of institutional educational change over time in the United States and Canada conclude that 'ultimately, the sustainability of large-scale educational change and reform of institutional culture can only be addressed by examining reform from a longitudinal change over time'. Hargreaves and Goodson (2006) argue that universities have been impervious to change because of their size, bureaucratic complexity and subject traditions. Producing 'deep improvement that lasts and spreads remains an elusive goal of most educational change efforts' over time (Hargreaves and Goodson 2006, p. 5).

Excellence and Equity

Challenges to the sustainability of any reform include personnel changes over time; student demographic shift; loss of funding and goodwill; and staff are suffering from reform fatigue. Hargreaves and Goodson's (2006, p. 5) findings conclude that many 'innovations can be successfully implemented with effective leadership, sufficient investment and strong internal and external support, yet very few innovations reach the institutional policy stage where they are routinely and become effortless'. The Adelaide experience suggests that change innovations can be implemented in university cultures, but their sustainability and long-term educational change over time remain to be determined and remain inconclusive.

Summary Case Study Characteristics

Paper presented at the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Mathematics Alliance National Conference, University of Wollongong. Retrieved from: http://www.adelaide.edu.au/wirltuyarlu/docs/Wilto_Yerlo_2012_Indigenous _Education_Statement.pdf. Tarrkarri Tirrka (Future Learning): The University of Adelaide integrated the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander education strategy.

Indigenous Knowledges, Graduate Attributes and Recognition of Prior Learning

2012, p. iv) also suggests that universities develop "Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Teaching and Learning Frameworks that reflect the inclusion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander knowledge in curricula, graduate attributes and teaching practices." In the higher education sector, RPL is more widely considered to contribute to advanced status (or credit). A university states that its policy on advanced status for prior studies and recognized prior learning recognizes that prior formal studies and RPL can contribute to further formal studies and to establish the equivalence of academic achievement regardless of the similarities or differences between the educational processes involved (James Cook University 2015).

Literature

Nakata (2004) believes that “the entire field of indigenous knowledge is controversial.” P. 19) and warns of what can be achieved in higher education 'in terms of controlling indigenous content or shaping knowledge and practice to be uniquely and identifiably indigenous' (Nakata 2007a, p. 225). Definitions of recognition of prior learning in higher education range from rather strict notions of credit to views of it as “a reflective process with an impact on the learning process” (Stenlund 2010, p. 784). 1 My use of RPLAS encompasses the literature relating to issues surrounding RPL in higher education.

Approach

Pouget and Osborne (2004, pp. 58-59) suggest that the higher education sector must respond 'to the need for a single credit system – the single currency, rather than the exchange rate mechanism – that recognizes performance in all areas'. Valk (2009, p. 88-89) believes that although universities have policies that recognize RPLAS, few put them into practice, with much 'high-level scientific and political discussion, but much less action.' The analysis of Valk (2009) points to some obstacles: the general focus of higher education provision, staff attitudes, staff workload issues and financial considerations. Pitman and Vidovich (2012, p. 771) argue that universities “enact policies symbolically, to take positions, rather than for any pragmatic reason.”

Outcomes

A stand-alone course would be one where IK is central, for example a Bachelor of Indigenous Studies, which is designed to communicate and create a better understanding of Indigenous worldviews. Social and Ethical Responsibility and Understanding Indigenous and International Perspectives (Queensland University of Technology). Students' and staff's knowledge and understanding of Indigenous Australian cultures, histories and contemporary realities and awareness of Indigenous protocols combined with the ability to engage and work effectively in Indigenous contexts in accordance with the expectations of Indigenous Australian peoples (Universities Australia 2011, p. 3 ).

Discussion Tensions

The interpretation of a knowledge claim in recognition of prior learning (RPL) and the impact of this on RPL practice. Integrating assessment and recognition of prior learning in South African higher education: A university case study. Recognition of prior learning (RPL) policy in Australian higher education: the dynamics of position-making.