As shown in the empirical chapters, market availability for mushrooms is not a challenge in Swaziland. I am equally indebted to the enumerators and respondents whose participation in the study made the research process a tremendous learning experience.

DOES ORGANISATIONAL FORM OF FARMER GROUPS AFFECT PRODUCERS’ PARTICIPATION IN COLLECTIVE RESPONSIBILITIES?

LIST OF TABLES

LIST OF APPENDICES

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS

INTRODUCTION

First cultivated in Germany in the 1900s (Eger et al., 1976), the oyster mushroom (Pleurotus spp) is known for its aromatic flavor and savory flavor. They include substrate collection, cutting, mixing, drying, sterilization/pasteurization and spawning (see Gwanama et al., 2011, for details).

THE RELEVANCE OF VALUE CHAIN ANALYSIS, TRANSACTION COSTS, AND COLLECTIVE ACTION IN PROMOTING

SMALLHOLDERS’ PARTICIPATION IN HIGH-VALUE AGRICULTURAL MARKETS

Introduction

The value chain concept and analysis methods

- The value chain concept

- The evolution of value chain analysis methods

- The dimensions of value chain analysis

13 used interchangeably with 'supply chain', the former relates to value creation via innovation in production, processing and marketing (Webber and Labaste, 2010). There are generally three main components that are examined in the value chain analysis (Kaplinsky and Morris, 2001; Rich et al., 2011).

Transaction costs in high-value agriculture

- Transaction costs defined

- Sources of transaction costs in the production and marketing of high value agricultural commodities

- Measuring/quantifying transaction costs

- The process leading to collective action in smallholder agriculture

Proportional transaction costs vary depending on how much an economic entity sells or buys (Key et al., 2000). Perishable products are usually associated with high transaction costs due to rapid transportation (from production to consumer centers) and cold storage requirements (Pingali et al., 2005).

Summary

DETERMINANTS OF FARMERS’ PARTICIPATION IN OYSTER MUSHROOM PRODUCTION IN SWAZILAND: IMPLICATIONS

- Introduction

- Methodology

- Conceptual and empirical model

- Data collection

- Empirical results and discussions

- Descriptive statistics of variables used in the Two-Stage Conditional Maximum Likelihood and Two-Stage Probit Least Squares regression models

- Farmers’ perceptions towards mushroom production

- Determinants of farmers’ participation in oyster mushroom production

- Summary

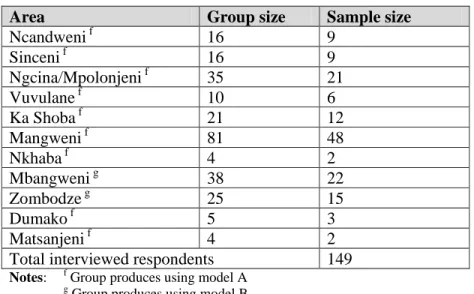

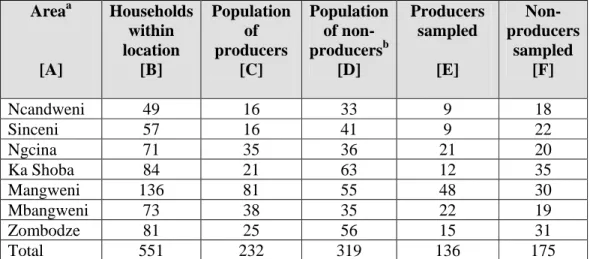

In contrast to the 39 total mushroom growers reported in 2008 (see Section 1.1), MDU records showed that the number of growers had increased to 271 in November 2010 (MDU, 2010). After determining the total number of households within each location, the procedure of Krejcie and Morgan (1970) was again used to determine the sample size for each location, where the resulting number of respondents was smaller (minus) the households already identified as mushroom producers.

SOCIO-ECONOMIC AND INSTITUTIONAL FACTORS CONSTRAINING PARTICIPATION OF SWAZILAND’S

APPLICATION OF THE VALUE CHAIN APPROACH 7

- Introduction

- Data collection

- Empirical results and discussions

- Production phase

- Marketing of oyster mushrooms

- Distribution of gross margins along alternative mushroom marketing channels

- Institutional environment

- Possible interventions for upgrading the mushroom value chain governance and coordination system

- Summary

The first two subsections discuss the activities and associated constraints encountered in the production and marketing processes. Due to lack of stock from private traders, restaurants and hotels buy imported mushrooms from local supermarkets. It is also worth noting that the benefits achieved by intermediaries are much less attractive compared to those of other market participants in the value chain.

The main institutional factors limiting mushroom production and value addition are discussed in the next subsection. As one of the main players in the industry, the MDU can also take the initiative to start consultative forums with stakeholders in an effort to establish networks and synergies between value chain actors, and possibly forge strategic public-private partnerships (PPPs). In the absence of mushroom food safety regulations, this kind of trade could endanger the lives of consumers and the industry's reputation as desperate for revenue.

EFFECTS OF TRANSACTION COSTS ON MUSHROOM PRODUCERS’ CHOICE OF MARKETING CHANNELS

IMPLICATIONS FOR AGRICULTURAL MARKET ACCESS IN SWAZILAND 8

Introduction

Methodology

- Conceptual framework

- The empirical model

- Data collection

- Descriptive statistics of variables used in the Tobit and Cragg’s models

- Factors affecting channel choice and quantity supplied

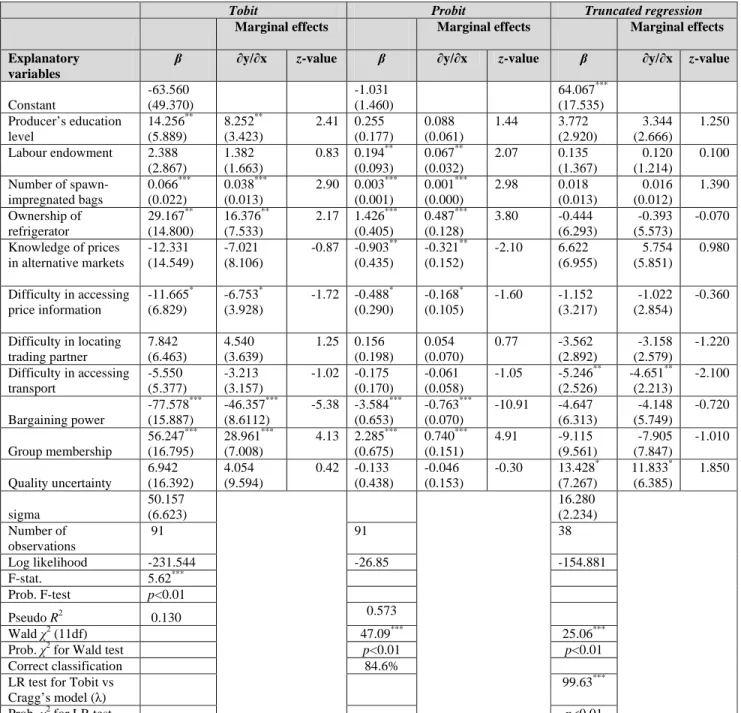

The first decision relates to the choice of a marketing channel and the second to the quantity of product to be supplied through the chosen channel. Within a simultaneous decision-making framework, the dependent variable is captured as the proportion of merchandise sold through the preferred channel. Tob's key underlying assumption is that the probability of channel choice also increases the average quantity of the good supplied; thus, the effect of a given variable will be the same on the choice of marketing channel and on the quantity supplied ratio (Burke, 2009).

After the reclassification by preference, two marketing channels appeared to be prominent: supermarkets (or retail outlets) used by 53 percent of respondents and the farm used by 47 percent. It begins with an overview of the descriptive statistics of variables used in the analytical model, followed by a discussion of the significant factors influencing producers' channel choice and the quantity of mushrooms supplied. The empirical results and discussion of the effects of transaction costs on producers' channel choice and the quantity of mushrooms supplied are presented in the next section.

Summary

Contrary to previous findings (e.g. Hobbs, 1997 and Gong et al., 2007), the coefficient for quality uncertainty was positively related to the quantity of mushrooms sold through the retail market. As observed by Staal et al. 1997), it can be concluded that although producers are often uncertain whether their mushrooms will meet the buyers' expectations for quality, the market reliability and relatively better exchange price offered by the retail market seem to outweigh the uncertainty about quality, such that producers are willing to increase their supply to avoid the farm gate option, which relies mainly on unpredictable consumer turnout. 82 Producers' decisions about the quantity of mushrooms supplied by the retail market were found to be negatively influenced by the difficulty of accessing transport and positively influenced by producers' uncertainty about the quality of the mushrooms.

Although the latter finding was against a priori expectations, this could be an indication that regardless of producers' uncertainty about whether their mushrooms will meet those of buyers. As such, producers are willing to increase their supply to the retail market to avoid the possibility of farm gate, which mostly relies on unpredictable consumer participation. The next chapter examines the effects of organizational form on mushroom producers' participation in collective responsibility.

DOES ORGANISATIONAL FORM OF FARMER GROUPS AFFECT PRODUCERS’ PARTICIPATION IN COLLECTIVE

RESPONSIBILITIES? EVIDENCE FROM SMALLHOLDER MUSHROOM PRODUCERS IN SWAZILAND 9

- Introduction

- Methodology

- Empirical results and discussions

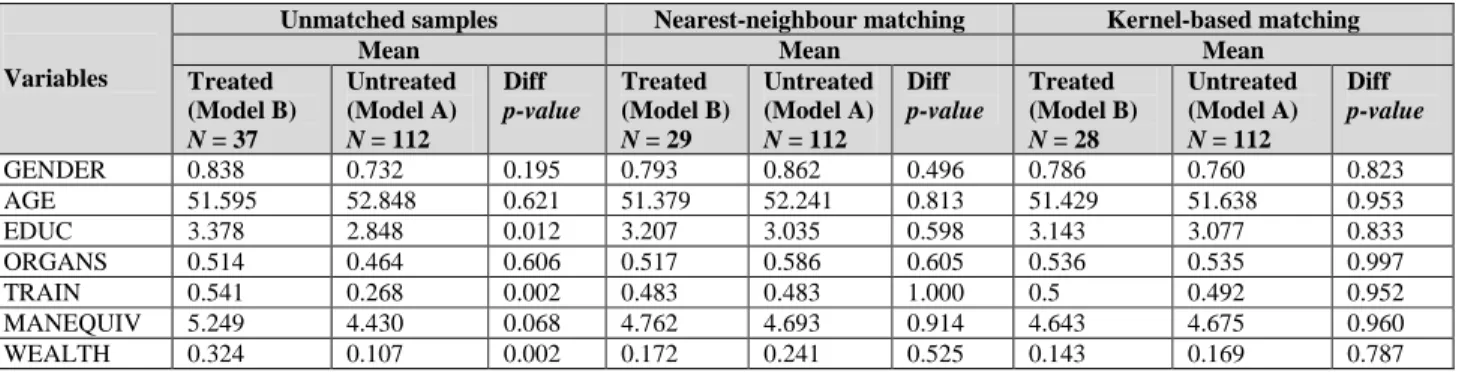

- Descriptive statistics for variables used in the Logit model and Propensity Score Matching method

- Factors that influence members’ participation in different group forms

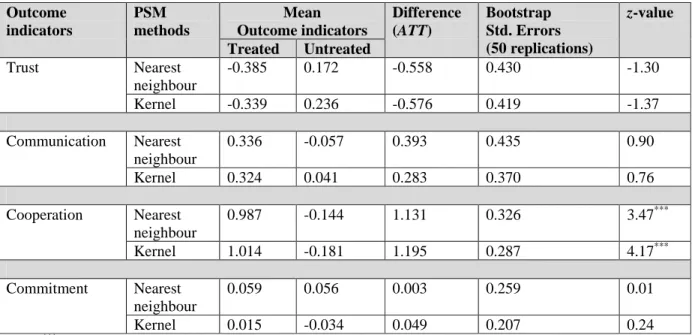

- The effect of group form on collective action

- Summary

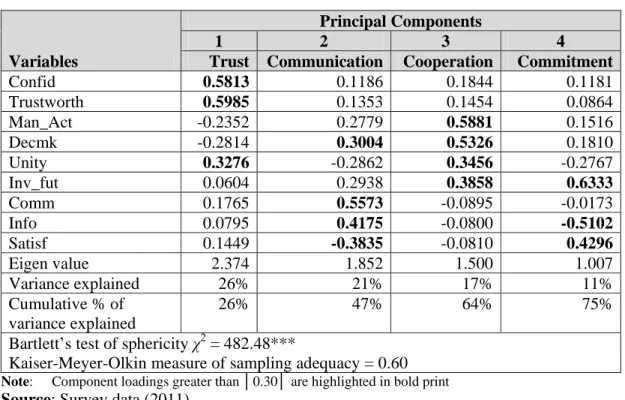

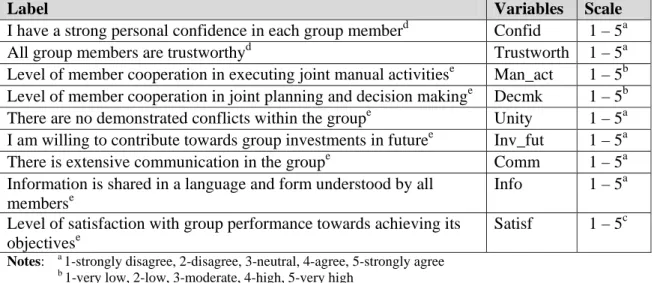

Also in this section, the variables used in the Logit model are discussed, followed by the empirical results of the Logit and PSM models, respectively. The third PC, which explains 17 percent of the variation in the original variables, represents cooperation. The fourth PC, which explains 11 percent of the variation in the original variables, represents the level of commitment of members in performing collective activities.

90 The next sub-section discusses the variables used in the Logit model and the PSM method. Apart from the collective action indicators (PC1 - PC4), all the variables discussed in the next sub-section and summarized in Table 6.4 were used in the Logit model to estimate the propensity scores. The effects of group form on collective action are presented in the next sub-section.

CONCLUSIONS, RECOMMENDATIONS AND OUTLOOK

Re-capping the purpose of the study

101 transaction cost factors that influence mushroom producers' decisions about choosing a marketing channel and the amount of mushrooms sold in the chosen channels; and (iv) examining the effects of organizational form on producer participation in shared responsibility. First, in the third chapter, the two-stage conditional maximum likelihood and the two-stage least squares probit approach were used to analyze the factors influencing household decisions to participate in mushroom cultivation. These two models were adopted after the discovery of a certain endogeneity between the decision to produce (dichotomous dependent variable) and producers' perception of mushrooms (continuous explanatory variable created by principal component analysis).

Second, a value chain approach was used in chapter four to study the underlying constraints of mushroom production and market access. Third, Cragg's regression model was applied in the fifth chapter to examine the effects of transaction cost factors affecting mushroom producers' market channel choice decisions and the quantity of mushrooms sold in selected channels. Finally, the propensity score matching method was used in chapter six to study the effects of organizational form on manufacturers.

Conclusions

- Determinants of farmers’ participation in oyster mushroom production

- Factors constraining mushroom producers’ participation in mainstream markets

- Effects of transaction costs on mushroom producers’ choice of marketing channels

Other limitations are related to the lack of diversification, as farmers currently only produce oysters, while consumers are mainly interested in the mushroom, which is popular for its appearance and taste. Although not directly involved in the production and distribution of products and services in the industry, some organizations are likely to influence the institutional environment and consequently the performance of certain activities by other actors in the value chain. Such organizations were identified in the study as MDU, Food Science and Technology Unit (FSTU) and National Agricultural Marketing Board (NAMBoard).

Processing and value addition in the mushroom industry is further constrained by Swaziland's unfavorable regulatory framework. However, despite Swaziland importing over 240 tonnes of cultivated mushrooms consumed locally, worth about E2.4 million annually, no tangible investment has been made by NAMBoard in the mushroom industry so far. The negative and significant coefficient for bargaining power suggested that the insufficiency of market information denies producers the opportunity to bargain for exchange prices in the retail market; thus, prices and terms of exchange are dictated by buyers.

Policy recommendations

- Intensification of farmer training and extension services

- Coordination of mushroom production and marketing

- Public-private partnerships in the mushroom industry

Besides improving producers' access to these inputs, this step will provide opportunities for local entrepreneurs to participate in the value chain and contribute to job creation in other economic sectors. Since producers are sparsely distributed and independently supply different volumes of mushrooms to the retail market, there is a need to introduce some form of vertical coordination in the value chain. External support in the form of a facilitator who will provide, among other expectations, information and technical assistance is also required, as most of the mushroom producers are less educated and lack exposure to agri-business.

In view of the possible increase in the number of producers in the future, it is further recommended that NAMBoard resumes the marketing support from 2001, which according to government regulations could be financed by the taxes levied on the importation of mushrooms. As a complementary investment that responds to the empirical findings in Chapter Five, it is recommended that the government, in collaboration with the private sector and other development partners, establish an agricultural market information system (MIS) to help provide timely and reliable. Given the absence of a coordination mechanism in the mushroom industry's 12 years of existence, it is imperative that the government through the MDU take the initiative to bring all stakeholders on board in an effort to promote mushroom development.

Limitations of the study

The conditions of collective action for local communal governance: The case of irrigation in the Philippines. Collective action for rangeland management in mixed crop-livestock systems in the highlands of northern Ethiopia. Introduction: Development and meaning of NIE. eds.), The New Institutional Economics and Third World Development, 1−16.

Mapping and measuring social capital through collective action assessment to conserve and develop watersheds in Rajasthan, India. ed.), The Role of Social Capital in Development: An Empirical Analysis, 85–124. Alternative marketing options for small-scale farmers in the wake of South Africa's changing agri-food supply chains. Transaction costs and crop marketing in the communal areas of Impendle and Swayimana, KwaZulu-Natal.

Institutional support & Collective action

Institutional support) will be answered by individual producers and members of mushroom producing groups

Social capital-related attributes) will be answered by members of mushroom producing groups only

- Questionnaire-Mushroom buyers (Supermarkets and Middlemen)

152 8.10 Were you able to participate fully in all group activities in the last year? 153 8.15 Do you think you put less effort into the group now than when you joined. 155 8.22 To what extent do you agree or disagree with the following statements regarding your working relationship with other group members.

Decisions in the group are made by a few influential committee members. The management structure must be improved. Which of the following do you consider to be the biggest risks and challenges associated with your marketing channels? Do you have any idea who your buyers are and whether they add value to your product.