The views, opinions, findings and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this paper are solely those of the author. They do not necessarily reflect the views of the Institute for Governance and Policy Studies, School of Government or.

The Challenge

Priority is given to land and waterway margins that are highly prone to erosion, where permanent afforestation is environmentally beneficial (see Box 1 below for details). The total costs of inaction outweigh the immediate costs of taking action—in this case, planting permanent forest on erosion-prone land and waterway edges.

The Solution

The group is willing to accept the rigor of measurement and evaluation to access private investor capital as contractors for a Permanent Forest Bond. Therefore, they are convinced by the offer of a local social enterprise that employs ex-offenders as tree planting contractors, which uses its proven success to access capital through the Permanent Forest Bond.

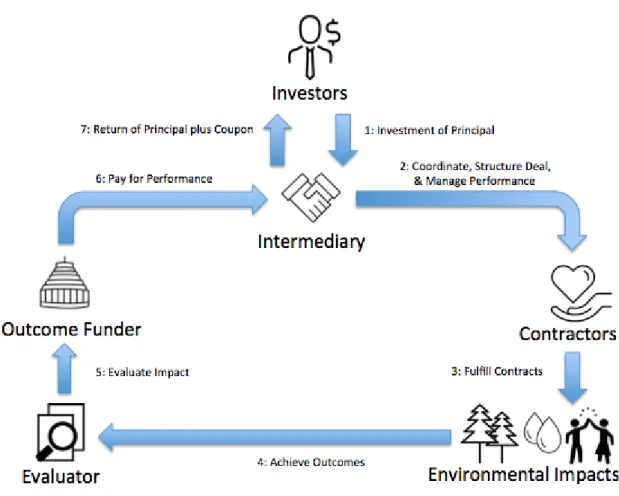

What is an Environmental Impact Bond?

3 This diagram is adapted from Emily Gustafsson-Wright, Sophie Gardiner, and Vidya Putcha, “The Potential and Limitations of Impact Bonds: Lessons from the First Five Years of Global Experience” (Washington, D.C.: The Brookings Institute, July https:/ /www. brookings.edu/research/the-potential-and- limitations-of-impact-bonds-lessons-from-the-first-five-years-of-experience-worldwide/ The Forest Resilience Bond (FRB) pilot project is currently Blue Forest Conservation in the United States.

The Precursor: the Social Impact Bond

Another frequent criticism is that SIBs are being rolled out as a replacement for existing programs, perhaps even a replacement for core funding. 14 Emma Tomkinson, “The Peterborough Social Impact Bond (SIB) Conspiracy,” Emma Tomkinson, October 27, 2014, https://emmatomkinson.com the-peterborough-social-impact-bond-sib-conspiracy/. Investing for Success: Social Impact Bonds and the Future of Public Services” (Wellington, NZ: New Zealand Initiative Dear et al., “Social Impact Bonds: The Early Years,” 21; and Emily Gustafsson-Wright and Sophie Gardiner, “Policy Recommendations for the Applications of Impact Bonds: A Summary of Lessons from the First Five Years of Experience Worldwide” (Washington, D.C.: The Brookings Institute, November 2015), 3–.

4, https://www.brookings.edu/research/the-potential-and-limitations-of-impact-bonds-lessons-from-the-first-five-years-of-experience-worldwide/. This working paper follows the lead of such research by treating environmental impact bonds as one instrument in a toolkit rather than as a solution. In other words, this working paper will not advocate the impact bond model as appropriate for all environmental infrastructure investments, nor as an alternative to mainstream environmental governance financing; instead, it explores the relevance of this financial instrument to the specific challenge of planting a permanent forest in New Zealand.

Whether impact bonds can be successfully adapted to other environmental challenges—such as the DC Water and Sewer Authority bond for green infrastructure—is beyond the scope of this paper. But when the object of the impact is natural resources, the value can also accrue to private companies, such as the water and electricity supplies in the forest's resilience bond.

Environmental Impact Bonds: Advantages and Risks

Advantages

Impact linkages are information-rich because the process of determining, measuring, and achieving impact measures will produce unique data about what works and what is most effective. However, from a policy perspective, it is advantageous that impact bonds are designed to demonstrate continued effectiveness over long-term time scales, not just short-term effects. A distinguishing feature between conventional government contracts and impact bonds is the relationship that service providers establish with private sector investors, actuaries and other intermediaries.

A common hypothesis for impact bonds is that pay-for-performance contracts are more likely to produce results than output-based contracts. In view of the novelty of these tools and the meager empirical evidence, this is only presented here as a hypothesis.19 A New Zealand Initiative report claims that “better results are more likely to be achieved” – but this appears to be based on a presumption that financial incentives work.20 In light of general research on human motivation, there is reason to doubt that this assumption is true in general, even though it could be true in specific situations.21 The main merit of impact bonds is not that success is more important. probably, but that failure doesn't have to be paid for. This has indeed been the case for Social Impact Bonds: “Most early trade investors are foundations and impact investors who have a higher tolerance for the risk associated with entering this market early, in addition to a desire to effectively solve complex social issues. seen addressed. .”22.

20 Jeram and Wilkinson, “Investing for Success: Social Impact Bonds and the Future of Public Services”, 7. A key asset for impact bonds is the potential for tailoring objectives to meet the expectations and demands of specific stakeholders.

Risks

A 2015 survey of existing impact effects noted that "choosing the simplest set of outcomes and measures possible makes the resulting SIB program significantly easier to operate. In relation to SIBs, the New Zealand Initiative notes: " It is more likely that the greatest benefit of SIBs, at least in the short term, will come from achieving better social outcomes, rather than fiscal savings. The transaction costs of SIBs can be high relative to the amount of capital raised, especially in the early stages of their development.”25 With regard to EIBs specifically, there is reason to believe that transaction costs can be somewhat reduced if the EIB can free. -ride on existing systems for environmental monitoring, rather than inventing new systems from scratch.

This is a risk that cannot be ruled out for permanent afforestation - but it can be mitigated through a judicious selection of indicators. The state's involvement in impact bonds as well as the long repayment cycle make impact bonds vulnerable to political risks. 25 Jeram and Wilkinson, “Investing for Success: Social Impact Bonds and the Future of Public Services,” 7.

Securing cross-party support for impact bonds will do much to instill investor confidence. While impact bonds can potentially be held hostage to the competing demands of parliamentary sovereignty and policy longevity, it must also be recognized that these risks are not unique to impact bonds.

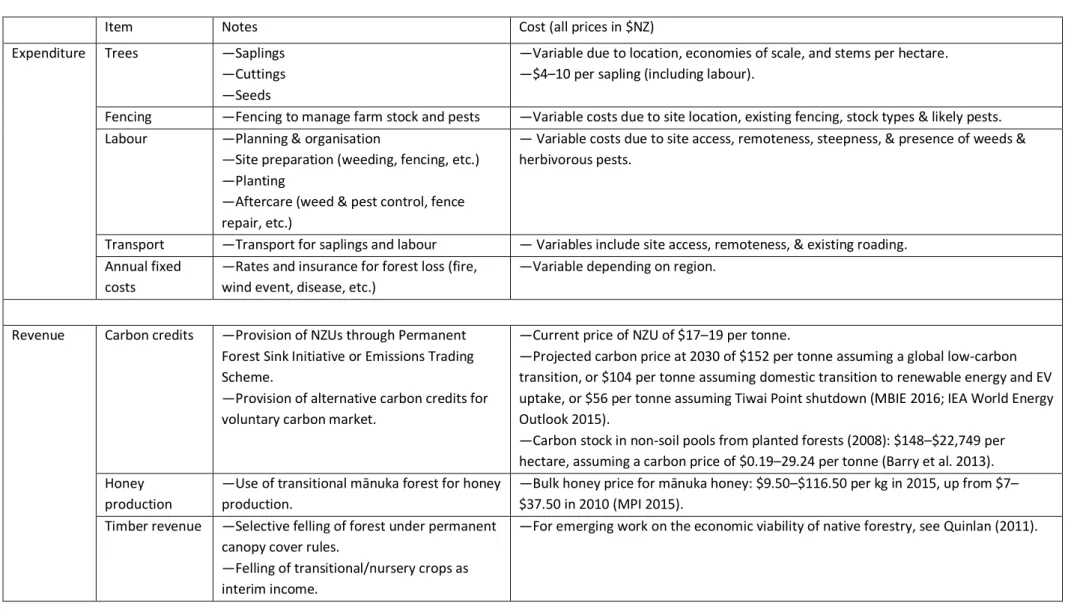

A Preliminary Indication of Expenses, Revenue and Avoided Costs

Revenue Carbon Credits—Provision of NZUs through Permanent Forest Sink Initiative or Emissions Trading Scheme. Total value of avoided erosion in perpetuity from future forest on 2.47 million hectares of erosion-prone land: $3.6 billion (Barry et al 2014). Avoided erosion value of 2.9 million hectares of erosion-prone land: $250 million per year (Barry et al 2013).

Average annual cost of soil erosion and sedimentation combined: $127 million, although the true value is likely higher. Net present value of soil conservation (for erosion and sedimentation): at least US$2.7 million at an internal rate of return of 11.3% (Weber et al 1992). One-off costs of the June 2015 storm in Taranaki/Horizons: total cost of $68.9 million with up to 800 properties affected.

Most impacted sheep and beef farms ($57.6 million) with $37 million in infrastructure damage and $20.6 million in production losses (MPI 2015). Total cost of Ministry of Environment's nine clean-up projects of polluted lakes and rivers (includes Lake Taupō, Rotorua Te Arawa Lakes and Manawatu River): $272.6 million; Crown contribution is $122.2 million.

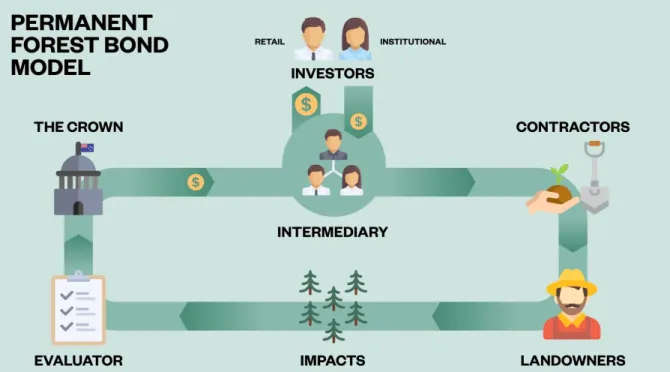

What Would a Permanent Forest Bond in New Zealand Look Like?

For the purposes of this working paper, this is appropriate because the details of the Permanent Forest Link can only be specified through the negotiation process. However, there are other interested parties who may be contracted into the Permanent Forest Liaison alongside the Crown. The Permanent Forest Link presents additional ownership issues related to intellectual property and carbon credits.

How to distribute ownership among stakeholders in the Permanent Forest Bond will be decisive for the distribution of benefits and therefore decisive for the Bond's attractiveness to potential participants. Alternatively, landowner forest ownership could be paired with mandatory registration with a pact, such as the Permanent Forest Sink Initiative or the QEII pact, to best guarantee the longevity of the forest. Intellectual Property: The Permanent Forest Bond is rich in information and generates evidence of effective forest practices.

Carbon credits: An important potential source of revenue for permanent forest is the generation of carbon credits to be sold on voluntary carbon markets or compliance markets such as the Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS). After that, landowners must forcibly enter the forest in the Permanent Forest Sink Initiative and acquire all subsequent credits.

Conclusion

The International Context

During COP21 in Paris, a group of asset owners and investment managers overseeing a combined US$11.2 trillion in assets issued the Paris Green Bond Statement, pledging to “increase investment in green bonds, climate bonds and other bonds that finance climate change mitigation and adaptation that meet the risk and return requirements of institutional investors.”38 The Climate Bonds Initiative, which co-organized this statement, is currently in the process of developing standards for green bonds, which consist of a certification process, pre-issuance requirements, post-issuance requirements and a set of sector-specific eligibility documents and instructions. Sectoral standards for solar, wind, low-carbon buildings, geothermal energy and low-carbon transport are already fully operational. These rules seem likely to remain a feature of future international climate frameworks; Indeed, New Zealand relies on the existence of these rules to purchase carbon credits in the coming decades to offset national emissions.

However, there is a tension between New Zealand's willingness to commit to emissions reduction targets under the Paris Agreement, yet its reluctance to produce domestic carbon sinks. Why give up future generations to buy offsets at an unknown price when we can create our own domestic offsets by creating permanent forests on marginal land. Projected carbon prices used for official planning should give fair warning: a recent MBIE report used 2030 carbon price projections of $56-152 per tonne41 while the BusinessNZ Energy Council assumes a 2050 carbon price of 60-115 dollars by 2050 for his predictions.42.

The Permanent Forest Bond could also be scaled up not only in New Zealand, but internationally, replicated in other countries with marginal land suitable for permanent forest. A 2030 carbon price of US$152 per tonne assumes a global low-carbon transition, US$104 per tonne assumes a domestic transition to renewable energy and electric vehicle use, and US$56 per tonne assumes the shutdown of Tiwai Point.

Comparison of Afforestation Schemes

New Zealand's Indigenous Forests and Lands.” In Ecosystem Services in New Zealand - Status and Trends., 34–48. 34; Quantifying the Benefits and Costs of Flood and Erosion Reduction of Climate Change Mitigation Measures in New Zealand." Report prepared by Blaschke and Rutherford Environmental Consultants for MfE. BusinessNZ Energy Council, Pauls Scherrer Institute, PricewaterhouseCoopers NZ, & Sapere Research Group, "New Zealand Energy Scenarios: Navigating the Energy Future to 2050".

Bonds and Climate Change: The State of the Market in 2016." Climate Bond Initiative & HSBC Center of Excellence for Climate Change, July 2016. Policy Recommendations for the Use of Impact Bonds: A Summary of Experience from the First Five Years of Global Experience.". The Potential and Limitations of Impact Bonds: Lessons from the First Five Years of Global Experience.” Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution, 9 July 2015.

Investing for Success: Social Impact Bonds and the Future of Public Services.” Wellington, NZ: New Zealand Initiative, 2015. Muddy Waters: Estimating the National Economic Cost of Soil Erosion and Sedimentation in New Zealand.