They differ only in the technologies used to connect the "last mile" to the end consumer. Presentation to the 1st Asia-Pacific Regional Conference of the International Telecommunications Society, Wellington, New Zealand, 28 August 2010.

Part B: Responses to the Discussion Document

Policy principles

For a discussion of the application of these models to infrastructure regulation, see Guthrie Guthrie, G. Consequently, ex-ante specification of a single specific and enduring "sustainable industrial structure" is likely to be detrimental to the long-term sustainability of the industry. 28 For a discussion of the ways in which access regulation and structural segregation can inhibit the pursuit of economic efficiency, see

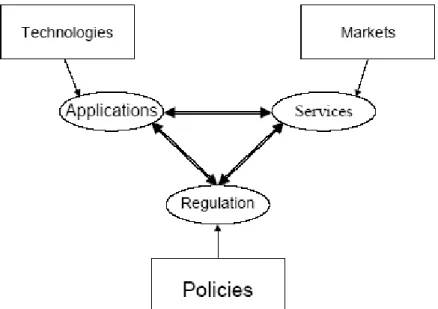

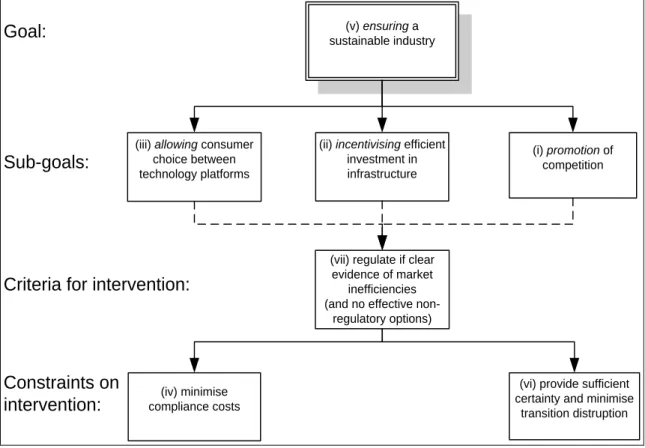

Thus, changes in industry structure in response to environmental changes are an important part of the competitive process. Therefore, we believe that the six principles fall naturally into a group of three sub-objectives, which relate to specific activities that can be observed in the interactions between industry participants, a definition of the criteria that justify regulation. These factors should be taken into account when assessing the degree of effective competition in a market.

The effects of access regulation in reducing incentives to invest in alternative competitive infrastructures are well documented37, leading to trade-offs in the pursuit of (ii) stimulating efficient infrastructure investment. Finally, we note that the market inefficiencies test cannot be applied without a clear specification of the market that is believed to embody inefficiencies.

Relationship with regulatory regime for UFB networks

In the New Zealand context, the companies that invested most aggressively via unbundling provisions were already extensive infrastructure owners before the option to invest in parts of the copper network was made available (Vodafone, TelstraClear, Kordia/Orcon). The "failure" of the "ladder" model further highlights fundamental inconsistencies between the rules of the copper network and the UFB, leading to some very perverse consequences. It is noteworthy that none of the predominant players in separation have participated in the UFB tender project as capital investors.

Furthermore, if the effect of the UFB policy is to impose infrastructure competition without Telecom's competitors having to 'climb the ladder', it begs the question whether the 'ladder' has any further meaning in the New Zealand regulatory environment. If the "ladder" is no longer applicable, at least in those markets where infrastructural competition exists and the UFB intended to create such infrastructural competition, then what is the purpose of maintaining regulated access arrangements, functional separation and equivalence provisions. It is to be expected that the nature of the relationship between Telecom and its LLU customers in the context of infrastructure competition may change from competitors on the copper platform to willing allies.

The implications of structural separation

At the very least, such cooperation is expected to mitigate the risk of blocking their existing assets. Telekom's voluntary divestiture response is not what would normally be expected in a regulatory environment aligned with the pursuit of efficient infrastructure competition. It can be seen as symptomatic of a response to a policy that is not in itself clearly consistent with an overall objective of increasing efficiency.

The response to structural decoupling should be seen as a case where policy and regulatory interventions will necessarily change the way an industry interacts, but the result may not be consistent with the general principles of effective and appropriate regulation, especially if the policies themselves have not been properly evaluated. in accordance with the principles defined in Chapter 1 above. While the costs of foreseeable risks are most effectively allocated to the party whose decisions lead to their invocation, it is rarely most efficient for one party to bear the unpredictable risks alone without adequate compensation. If the costs of unpredictable risks are not effectively allocated or compensated, then policy sub-objective (ii) of promoting efficient investment is unlikely to be met.

The appropriate form of cost-based bitstream pricing

In order to maintain relativities so that both platforms can continue to enjoy equal incentives, it is the prices of the UFB network that must be regulated to prevent the occurrence of unproductive arbitrage between the networks. With regard to regulatory arbitrage, we express concern about the trade-off likely to arise from structural and functional segregation obligations on both the copper and fiber networks. Because the UFB policy restricts retailers' ability to invest in the fiber networks, and the "investment ladder" has failed to trigger substantial new investment in the copper network, the risks of regulatory arbitrage under the currently proposed arrangements appear significant.

The manner in which the regulator should respond depends crucially on the dominant objective of the government's investment in UFB. If the goal is to promote infrastructure competition, then the appropriate response would at least be to eliminate the copper network's non-discrimination provisions and prices that ensure balance between networks is maintained so that the subsidized is not an artificial advantage. If the goal is instead to rapidly replace the copper network, then relativity is irrelevant - copper and fiber network prices must be structured to crowd out all future copper network development in favor of mass migration to UFB.

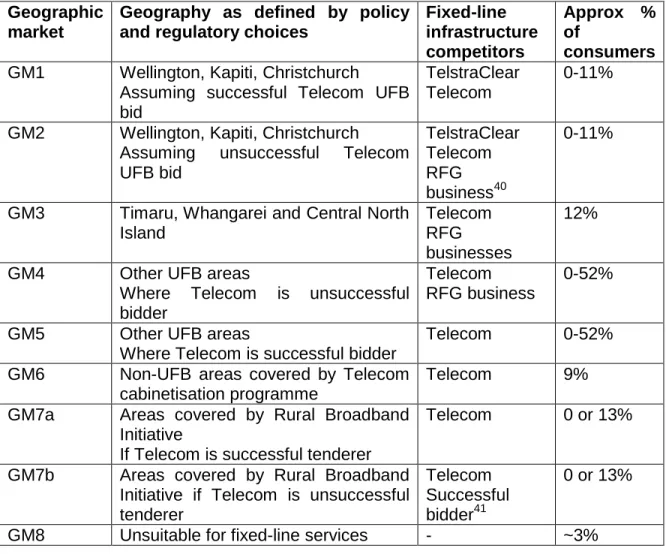

Averaged or de-averaged cost-based prices 46

Indeed, the assumption that there will be as many as 33 separate regions operated by different firms, and that the national average would require transfers between them, tends to suggest that there will be no national average of UFB wholesale prices. . If they are not, then there will be different arbitrage opportunities in different geographic locations depending on the set of rules that apply to each network, leading to an eventual fragmentation of network provision across the country. Specifically, the low-priced network will not be able to compete in rural areas, as its costs will be unsubsidized, while in urban areas, the medium-priced network will not be able to compete, as the costs his should be artificially inflated. for the creation of subsidies applied to rural areas.

The end result is that infrastructure competition will be eliminated - the averaged network will be the only network in urban areas and the averaged network will be the only network in rural areas. Since the objective of average prices in the first place is to enable a nationally consistent set of retail prices (essentially a "universal service price"), even this objective fails, as under these facts the prices for each region will become local cost-based. Given the above assumptions about the likely de-averaging national UFB wholesale prices, it appears that the only logical option is to continue with de-averaging prices on the copper network.

The current TSO framework

Insofar as the structural separation calls for a vision of how the existing TSO obligations should be distributed among the various remaining activities, we address points i to iii above. If the aim of the structural separation is to create a telecom retail company directly equivalent to any other retail operator, it seems to make little sense to maintain retail price controls on Telecom, but not on those of its (otherwise equivalent) retail competitors , since competitive processes will lead to a result that the equivalent result is more efficient. If the rate is introduced because it meets market demand, no regulation is needed to maintain it.

The remaining question is to what extent the costs of meeting the universal service price obligations are distributed. If universal service prices are introduced at retail level, wholesale prices must also be universal in order to be passed on to the network operator. If the network operator is the sole supplier of connectors to all (equalized) retailers, transfers can be made internally, so that receipts from low-cost customers are used to cover the cost of supplying expensive connectors below cost.

Funding the Local Service TSO obligations

For a single, integrated nationwide network that faces no competition, it is simple for "average" retail prices to recover wholesale and network operating costs. Since universal service pricing is a retailing instrument that affects a transfer of wealth from urban to rural customers, if it is asymmetrically distributed among retailers, it will inevitably have negative selection consequences ( "skimming the cream" or "picking the cherry"). at the network level. We note at this point that a continued obligation of the copper network operator to be the connector of last resort imposes some special stresses, again, these stresses stem from UFB, and the confusion as to whether it is an infrastructure competitor or a successor to directly from the copper network.

Since the separated network operator cannot have a direct relationship with retail customers, and the presumption is that competition will prevail and is limited by competition law in its ability to form relationships with fiber operators to progress, it is unlikely to be able to leave easily. from the market when it is economically efficient to do so. It is our view that the whole issue of assigning the obligations to be the provider of last resort – at both network and retail level – needs to be rethought to take into account all the increasing competition, technological innovation and network evolution. At the very least, it is becoming clearer that the changing face of competition across the country means that it is highly unlikely that one chain or one retail firm will be able to meet such obligations and remain financially viable.

Part C – Appendix