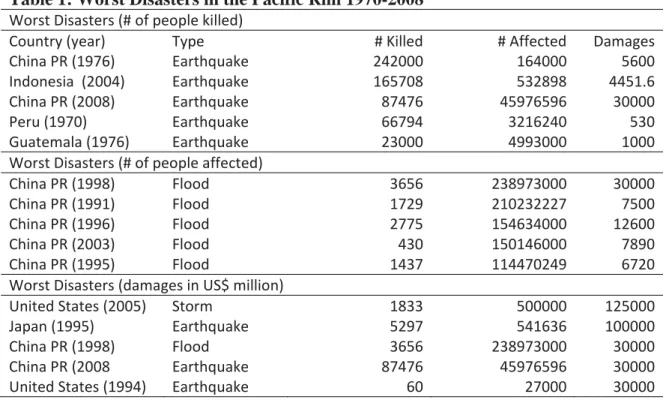

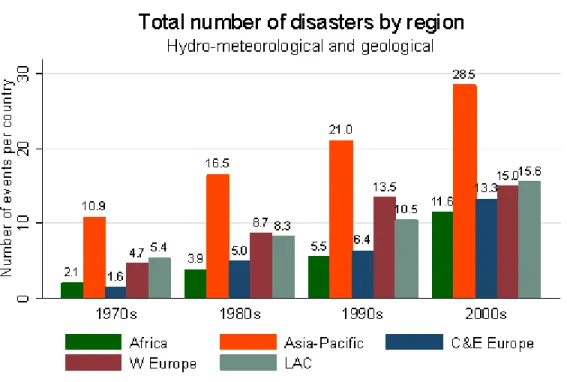

Many of the most devastating natural disasters of the past few decades occurred on the Pacific coast. During the last century, for example, the deadliest earthquake (Tangshan, China, 1976), the deadliest tsunami (Aceh, Indonesia, 2004) and some of the. This region experiences by far most of the volcanic activity and ground movements recorded worldwide.

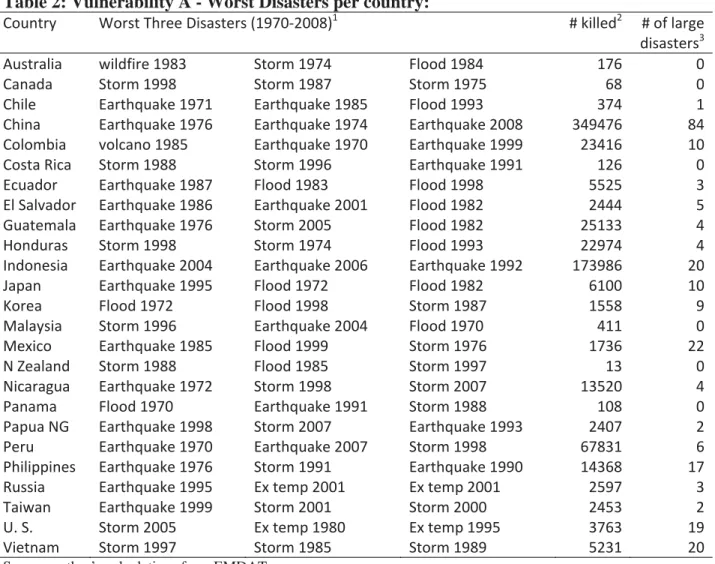

Understanding the history of disasters in the Pacific, their impact on development, the spatial evolution of income, and the risks facing the Pacific region in relation to future events and their potential consequences appear to be important components of a the meaning of the economy of the region. For a disaster to be entered into the EM‐DAT database, at least one of the following. We present disaster data for all Pacific Rim countries, but exclude small ones.

Africa." (IPCC, 2011).5 While the 2011 report is quite skeptical about the robustness of many of the predictions available in the scientific literature on catastrophic high-risk low-.

Determinants of Initial Disaster Costs

For example, if climate change causes longer and more widespread droughts, the resulting soil erosion will increase the damage caused when earthquakes trigger mudslides (as is often the case in Central America). This difference is most likely due to the greater amount of resources spent on prevention efforts and legal enforcement of mitigation rules (eg, building codes). In particular, some policy interventions that could mitigate the effects of disasters, including land use zoning, building codes, and engineering interventions, are less common in less developed countries.

Bangladesh clearly shows that even poor countries can adopt successful mitigation policies and that successful mitigation does not depend only on financial resources and the ability to mobilize them. In addition, the government discontinued the post-. disaster relief efforts and limited access by international NGOs to the affected area; more. They conclude that inequality is important as a determinant of prevention efforts: more unequal societies tend to have fewer resources spent on prevention, since they are unable to solve the collective action problem of implementing costly preventive measures and emollient.

Besley and Burgess (2002), using data from floods in India, observe that disaster impacts are lower when newspaper circulation is higher, leading to more responsible politicians and a government more active in preventing and mitigating impacts. Reinforcing this issue of accountability is the apparent unwillingness of voters to punish politicians who had underinvested in preparedness, while failure to provide generous funds for post-disaster reconstruction appears to be an important determinant of post-disaster electoral success (Healy and Malhotra. 2009 ). Thus, even in democracies, politicians rarely face the optimal incentives in terms of disaster prevention and/or mitigation.

To summarize, while damage caused by disasters is naturally related to the physical intensity of the event, a number of economic, social and political characteristics also affect vulnerability. In particular, the collective action problems that the literature identifies can potentially be overcome by designing decision-making mechanisms that take these problems into account. There is a growing awareness among Pacific Rim policymakers of the importance of not only mitigating, but also reducing vulnerability to the economic pain that is likely to follow a disaster.

Economic Impacts – Are Disasters a Poverty Trap?

Raddatz (2009) uses vector autoregressions (VARs) to conclude that smaller and poorer countries are more vulnerable to these spillover effects and that most of the output costs of climate events occur in the year of the disaster. The Chinese government has spent heavily on reconstruction, noting that while small disasters can have a positive effect on average (due to the incentive to rebuild), large disasters always have serious negative economic consequences in their immediate aftermath. While direct losses may be high in large countries due to the increased exposure of assets, the greater capacity to absorb shocks means that indirect losses may be lower and/or that the magnitude of damage may be smaller relative to the size of the country.

Nevertheless, endogenous growth models of the AK type, in which technology exhibits constant returns to capital, predict no change in the growth rate after a negative capital shock; although an economy that experiences fixed capital destruction will never return to its previous growth path. Endogenous growth models, which have increasing returns to scale of output, generally assume that the destruction of some physical or human capital results in a lower growth path and a consequent permanent deviation from the previous growth path. Skidmore and Toya (2002) explain their somewhat counterintuitive finding by suggesting that disasters may accelerate Schumpeter's process of “creative destruction” at the heart of the development of market economies. 2008) note that in developing countries, the occurrence of disasters is associated with less spillover of knowledge and a reduction in the amount of introduced new technology, but not with an acceleration of these processes. 2010) represents the most recent attempt to resolve this debate.

They implement a new method based on constructing synthetic controls—i.e. a counterfactual that measures what would have happened to the path of the variable of interest in the affected country in the absence of the natural disaster. Accurate estimates of the likely fiscal costs of disasters are useful to enable a better cost-benefit evaluation of various mitigation programs and to. On the expenditure side, publicly funded reconstruction costs can be very different from the original amount of capital destruction; while on the revenue side of the financial statements, the impact of disasters on taxes and other sources of public revenue has also rarely been studied quantitatively.

11 In addition to FONDEN, Mexico is also one of the largest issuers of CAT bonds. Odell and Weidenmeir (2004), in a historical investigation of the international impacts of the 1906 San Francisco earthquake and fire, describe how the shock spread to Europe as about 40% of the city's fire insurance policies were issued by European firms. (mostly from the UK). Several other papers examine various aspects of the international spread of economic shock that follows a natural disaster.

Even for foreign aid flows, Becerra et al. 2010) find that, on average, the increase in aid inflows after a disaster is significantly less than the amount needed to cover much of the cost of replacing destroyed property. For example, the Irish Famine prompted dramatic emigration from Ireland; and that migration proved to be irreversible and initiated a long-term decline of the Irish population (Ó Gráda and O'Rourke, 1997).

Policies and Open Questions

This framing creates the lack of preparedness we have seen most recently in the Fukushima nuclear power plant. In retrospect, it is obvious that the operators of the coastal power station should have had contingency plans in place for a failure of the power supply to both the grid and the emergency generators rendered useless by the tsunami. More generally, post-disaster energy supply difficulties and communication network breakdowns appear to be two aspects of this and other recent disasters that were not adequately planned for.

Vulnerability of industrial production, as exposed after this disaster, is the result of a dramatic increase in the vertical integration of production networks and just-in-time supply chain management. Besides a lack of preparedness and adequate risk mitigation, Kunreuther and Pauly (2009) examine some of the problems associated with ex-ante insurance coverage for major natural events: uncertainty regarding the extent of potential losses, highly correlated risk among the insured, moral hazard that leads to the taking of excessive risks by the insured, and an adverse choice of insured parties caused by imperfect information. As we have already pointed out, many major disasters have very small probabilities associated with them and this makes it difficult to develop relevant mitigation policies and also likely leads to underinsurance.

Investors collect the interest on the bond plus the insurance premium paid by the insured party while the disaster does not occur. However, if disaster strikes, their claim is extinguished and the SPV sells the bond and transfers the funds to the insured. 19 Katrina insurance claims data are from Kunreuther and Pauly (2009), while the total claims figure is obtained.

Instruments that tie insurance payouts to measurable floods, for example, would greatly simplify the difficult and time-consuming sorting of insurance claims likely to follow the Bangkok floods of October and November 2011 - estimated at US$13 billion, perhaps the costliest flood event of the last decade in terms of to insured damages. What are the appropriate institutional arrangements that ensure the proper functioning of insurance schemes while at the same time reducing moral hazard and adverse selection. What is the appropriate role of government versus the private sector in catastrophe insurance markets.

Why Economic Dynamics Matter in Climate Change Damage Assessment: Illustration of Extreme Events." Ecological Economics. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. I: Special Report on Managing the Risks of Extreme Events and Disasters to promote adaptation to climate change.

The economic aftermath of the recent earthquake in Sendai, Japan.” European Business Review, May-June, 2011. Fiscal storms: public spending and revenues in the wake of natural disasters.” Environmental and Development Economics. Are external shocks responsible for the instability of output in low-income countries?” Journal of Development Economics.

The Wrath of God: Macroeconomic Costs of Natural Disasters.” World Bank Policy Research Working Paper #5039. The impact of natural disasters on human development and poverty at the municipal level in Mexico. 3 Measure the number of disasters that killed more than 100 people, affected more than a thousand people, and caused damage in excess of $1 million (this is a significantly higher threshold than the one used by EMDAT – we have no further done). count disasters for which the fatality count was not available).