THE STRUCTURE OF THE TOBA

BATAK CONVERSATIONS

A DISSERTATION

Submitted to the Department of Linguistics of The Graduate School of

North Sumatera University in partial fulfillment of the requirements

for the degree of Doctor in Linguistics

HILMAN PARDEDE

REG. NO. 078107003

GRADUATE SCHOOL

NORTH SUMATRA UNIVERSITY

MEDAN

ABSTRACT

This disertation focuses on Conversation Analysis (CA) regarding the structure of Adjecancy Pair (AP) and Turn-Taking in Toba Batak (TB) conversations. The aims of the research are to explain: a) how the AP of TB conversation operates, b) how the end of turn is grammatically, intonationally, and semantically projected, and c) how the Turn-Taking in TB conversation operates. The main theory used is CA theory by Sacks, Schegloff, and Jefferson (1974). This theory assumes that there are four basic assumptions in conversation, they are: a) conversation is structurally organized, b) conversation is jointly produced among participants, c) conversation is contextual, and d) conversation is locally managed. Since conversation is structurally organized and sequentially constrained, there can be found structural approach, that is, adjacency pairs. This exemplifies structural organization as well as orderly sequence of interaction in conversation. Adjacency pairs give slot to the next position whether responded or not. When the first is not responded, the second would be noticeably absent, that leads to a repair actions. As the joint production among participants, recipients show his or her intersubjectivity as the understanding and inferences of the the speaker’s utterance. Again, when recipients do not show his or her intersubjectivity, the speaker may reply with repair work in the next slot, which is called the third position repair. Since conversation is locally managed, it implies that turn-by-turn organization of conversation are analyzed.

The research was conducted using qualitative method. The data were collected based on audio recording and video recording of mundane conversation or casual talk which constitute fifty texts of conversations. These texts are categorized into two, they are forty texts dealing with Adjecancy Pair and ten texts dealing with Turn-Taking. The analysis is based on CA, that is sequential analysis.

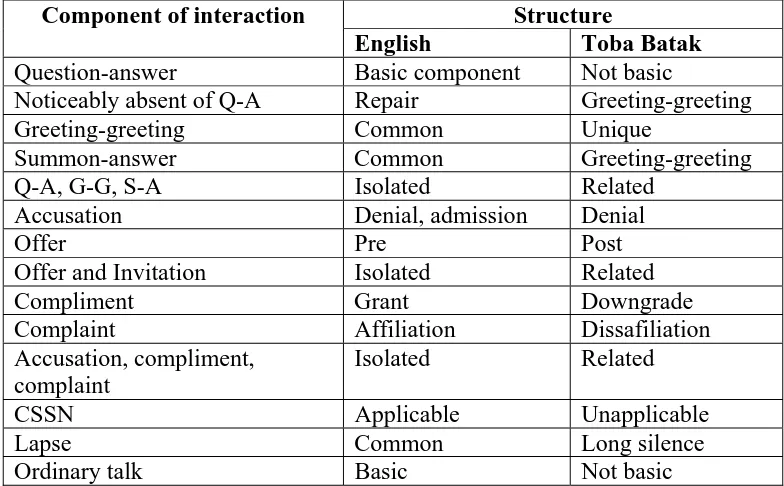

silence occurs in lapse, 16) The ends of turn which are grammatically, intonationally, and semantically projected occur in TB conversation, 17) The rules of Turn-Taking and the organization such as silence, overlapping talk, and repair are applicable in TB conversation, 18) Turn-taking are not culturally bound.

The findings imply that learning the adjacency pairs of foreign language can not depend only on the mechanical structure, but on the ritual constraint, and this is also effective in the first language (TB). On the other hand, there is a room for turn-taking to be further studied based on ritual constraint.

It is concluded that there are negative cases in AP and turn-taking of TB.

ABSTRAK

Disertasi ini berfokus pada analisis percakapan yang mengkaji struktur pasangan berdekatan dan gilir berbicara dalam percakapan bahasa Batak Toba. Tujuan penelitian ini adalah untuk memerikan: a) bagaimana pasangan berdekatan dalam percakapan bahasa Batak Toba dipraktekkan, b) bagaimana akhir gilir bicara diproyeksikan secara gramatikal, intonasional, dan semantikal, dan c) bagaimana gilir bicara dalam percakapan bahasa Batak Toba (PBBT) dipraktekkan. Teori utama yang digunakan dalam penelitian ini adalah teori analisis percakapan oleh Sacks, Schegloff, dan Jefferson (1974). Terdapat 4 asumsi dasar dalam percakapan berdasarkan teori ini: a) percakapan terorganisasikan secara struktur, b) percakapan merupakan hasil produksi sesama partisipan, c) percakapan kontekstual, dan d) percakapan di kelola secara lokal. Karena percakapan itu terorganisir secara struktur dan dihadapkan pada urutan (sequence), maka ditemukan suatu pendekatan struktur yang disebut sebagai pasangan berdekatan. Ini menunjukkan organisasi struktur serta urutan interaksi yang teratur dalam percakapan. Pasangan berdekatan memberikan tempat kepada posisi/urutan berikutnya yang dapat direspon maupun tidak. Apabila yang pertama tidak direspon, yang kedua dapat dipertanggung jawabkan dan menimbulkan tindakan perbaikan. Sebagai produksi sesama partisipan, pendengar akan menunjukkan keterlibatannya karena mengerti ujaran pembicara. Apabila pendengar tidak menunjukkan keterlibatannya, pembicara akan melakukan tindakan perbaikan pada tempat berikutnya, yang disebut dengan perbaikan pada posisi ketiga. Karena percakapan dikelola secara lokal, hal ini mengimplikasikan adanya analisis giliran per giliran dalam percakapan.

Penelitian ini dilakukan dengan menggunakan metoda kualitatif. Data dikumpulkan dengan merekam secara audio dan video melalui percakapan kasual. Data yang dianalisis ada 50 data yang terdiri dari 2 bagian: 40 data digunakan untuk menganalis pasangan berdekatan, dan 10 data digunakan untuk menganalisis gilir bicara. Data dianalisis berdasarkan analisis percakapan, yaitu analisis sekuensial.

undangan mencakup tiga sekuen: perluasan awal, perluasan akhir, dan sekuen sisipan, 9) Pasangan tawaran dan undangan adalah berhubungan, 10) Pasangan tuduhan memiliki respon penolakan pada pasangan kedua sebagai yang diinginkan, 11) Pasangan pujian mempunyai respon penolakan yang dihaluskan pada pasangan kedua, 12) Pasangan keluhan mempunyai respon penolakan pada pasangan kedua sebagai yang diinginkan, diformulasikan dalam bentuk ketidakberpihakan, 13) Pasangan tuduhan, pujian, dan keluhan adalah berhubungan, 14) Kaidah pertama gilir-bicara (pembicara sekarang memilih pembicara berikut) tidak selalu dapat diaplikasikan dalam percakapan bahasa Batak Toba, 15) Kesenyapan panjang terjadi dalam percakapan yang terhenti sementara, 16) Akhir dari giliran yang diproyeksikan secara gramatikal, intonasional, dan semantikal terjadi dalam percakapan bahasa Batak Toba, 17) Kaidah gilir bicara dan organisasi seperti kesenyapan, percakapan tumpang tindih dan perbaikan dapat diaplikasikan dalam bahasa Batak Toba, 18) Gilir bicara tidak terikat secara kultural.

Implikasi temuan ini adalah bahwa belajar pasangan berdekatan bahasa asing dan bahasa pertama tidak dapat hanya tergantung pada struktur mekanis, tetapi juga harus tergantung pada hambatan ritual. Pada sisi lain, terbuka wacana untuk mengkaji gilir bicara berdasarkan hambatan ritual.

Dapat disimpulkan bahwa, terdapat kasus-kasus negatif yang menjadi temuan pada penelitian ini.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I wish to express my deep gratitude to all those who lent their assistance and

advice in the preparation of this work. First, the members of my dissertation advisors:

Prof. Amrin Saragih, MA, Ph.D as promotor, Prof. Tengku Silvana Sinar, MA, Ph.D as

co-promotor, and Prof. Dr. Robert Sibarani, MS as co-promotor.

Second, I would like to express my sincere appreciation to Prof. Tengku Silvana

Sinar, MA, Ph.D as chairman of Linguistic Program of Post Graduate school of North

Sumatera University for providing me access to learn from the beginning up to the end

of this study including the Sandwich Program I attended in USA.

I would like also to express my gratitude to Prof. Dr. Ir. T. Chairun Nisa, B.,

M.Sc for her effort so that I can enhance my knowledge in the beloved Post Graduate

school, especially when I could attend Sandwich Program in Auburn University,

Alabama, USA.

I am also indebted to the Rector of North Sumatera University, for the facilities

given that I could participate in any activities pertaining to all academic constraint in

the Post Graduate School.

Last but not least, I must express deepest gratitude to my wife, Lissa Donna

Manurung and my daughter, Claudia Benedita Pardede, for unfailing love, patience,

Hilman Pardede CURRICULUM VITAE

Hilman Pardede was born in Padang Sidempuan on May 25, 1960. He is the fourth son of Late BM. Pardede and Elfrida Lubis. He graduated from Elementary School SD Negeri No. 59 Pematangsiantar in 1973, Junior High School Methodist Pematangsiantar in 1979, Senior High School in Methodist Pematangsiantar in 1982, and S-1 English Program of North Sumatera University in 1987. In the year of 1992, he continued his study to S-2 Program of IKIP Malang , and graduated in 1994. Then he went to S-3 program in linguistics at North Sumatera University in the year of 2007. In 2008, he attended a Sandwich Program in Aurbun University, Alabama, USA. In 2010, he was a speaker in the International Seminar in Trang, Thailand. He presented a paper entitled “Adjecancy Pair in Toba Batak”

From 1987 up to 1989, he was appointed lecturer assistant in HKBP Nommensen University Pematangsiantar. Later in 1990, he became a permanent lecturer of HKBP Nommensen University Pematangsiantar. In 1998, he was appointed Head of English department of S-1 program HKBP Nommensen University Pematangsiantar. In his organization career, he was appointed as the President of Chistian National Party Pematangsiantar (KRISNA) in 1993. In 2001, he was appointed as Vice president of Christian Indonesia Party (PARKINDO) and as the Vice president of Democratic Party (DEMOKRAT) in 2006.

He has also done some field researches such as: 1) Sociocultural Values in Umpama of Toba Batak in 1994, 2) Syntactic Variation in Translation in 2008, 3) Differences Between Male and Female Speech in 2008. He wrote some books for students material, such as: 1) Semantics: A View to The Logic of Language, 2) Introduction to Sociolinguistics, 3) Understanding Noun and Adjective, 4) Some Uses of English Verb.

LIST OF FIGURES

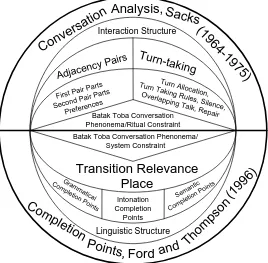

1. Figure 1: Theoretical Framework of The Study ……… 45

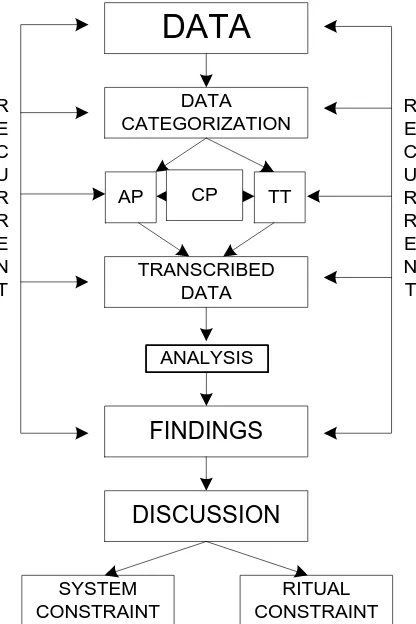

2. Figure 2: Data Analysis Procedure ……… 62

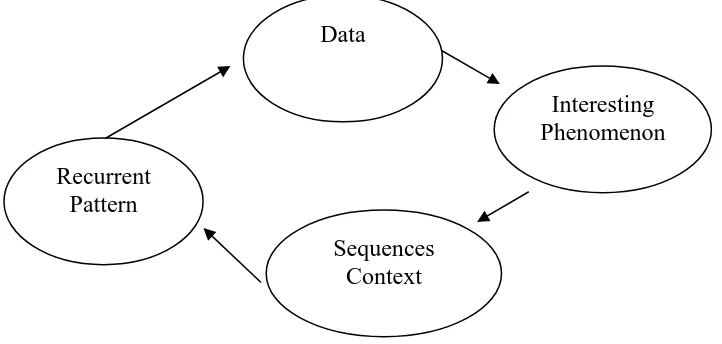

3. Figure 3: Ellaboration of Analysis Procedure ……… 63

LIST OF TABLES

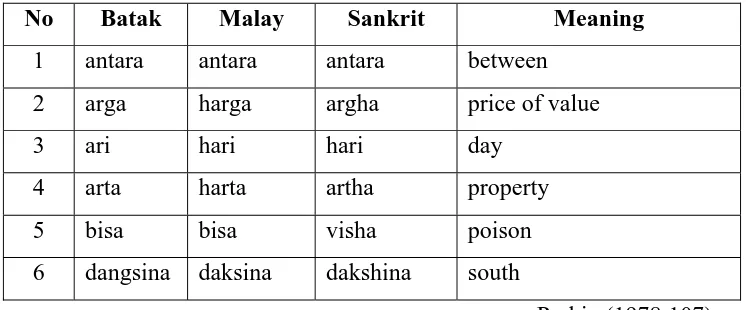

1. Table 1: Similarity between Toba Batak words, Malay, and Sankrit …… 38

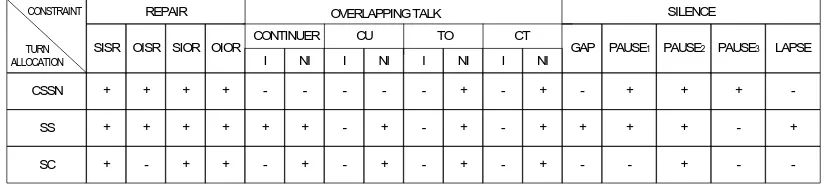

2. Table 2. Turn Allocation and Its constraint ……… 206

LIST OF CHARTS

1. Chart 1: Question-Answer ……… 181

2. Chart 2: Greeting-Greeting ……… 181

3. Chart 3: Summon-Answer ……… 182

4. Chart 4: Offer-Ac/Rj ……… 183

5. Chart 5: Invitation-Ac/Rj ……… 184

6. Chart 6: AP mechanism of Acc-D ……… 185

7. Chart 7: AP mechanism of Cpm-Rj ……… 185

8. Chart 8: AP mechanism of Cpn-Rj ……… 186

9. Chart 9: Relation among AP Mechanism in Q-A, G-G, S-A ……… 191

10. Chart 10: Relation between APs of Offer and Invitation ……… 194

11. Chart 11: Relationship among Ac-D, Cpm-Rj, Cpn-Rj ……… 197

LIST OF TRANSCRIPTION SYMBOLS

Sequencing

[ point of overlap onset;

] point of which utterance terminates

= no gap between lines (latching utterances). When the same speaker

continues on the next line latching signs are not used

Timed intervals

(0.0) Lapsed time in tenths of a second e.g. (0.5)

Speech production characteristics

word underline indicates speaker emphasis;

! animated and emphatic tone;

? rising intonation, not necessarily a question;

he..he.. laughter particles;

Continuers

e indicate intention to start a turn

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

In = Interruption NI = Non-interruption

CU = Collaborative Utterance TO = Terminal Overlap CT = Choral Talk

LIST OF MAPS

1. Map 1. The North Sumatra Province ……… 47

2. Map 2. The Regency of North Tapanuli ……… 48

3. M ap 3. The Regency of Humbang Hasundutan ……… 49

4. Map 4. The Regency of Toba Samosir ……… 50

LIST OF PICTURES

1. Picture 1. A conversation about papaya ……… 70

2. Picture 2. A conversation about asking direction ……… 71

3. Picture 3. A conversation at a fishing pool ……… 72

4. Picture 4. A conversation about statue ……… 110 5. Picture 5. A conversation in a coffee-counter ……… 111 6. Picture 6. A conversation about a coupon-number ……… 122

7. Picture 7. A conversation about a learning-driver and a new-comer …… 124

8. Picture 8. A conversation about tomatoes-planting ……… 125

9. Picture 9. A conversation about pension ……… 134

10. Picture 10. A conversation about poor-family ……… 140

11. Picture 11. A conversation about family ……… 145

TABLE OF CONTENTS

LIST OF TRANSCRIPTION SYMBOLS ………. x

LIST OF ABBREVIATION .……… xi

2.1 Relevant Approaches to Analyzing Conversation ……… 17

2.1.1 Conversation Analysis ……… 18

2.1.8 Systemic Functional Linguistics ……… 24

2.1.9 Critical Discourse Analysis ……… 25

2.2. Conversation ……… 26

2.2.1 Characteristics of Conversation ……… 26

2.2.2 Assumption in Conversation ……… 28

2.3. Adjacency Pairs ……… 30

2.4. Turn ……… 33

2.5. Turn – Taking ……… 34

2.6.1 Toba Batak Language ……… 36

CHAPTER IV THE STRUCTURE OF ADJACENCY PAIRS AND TURN-TAKING IN TOBA BATAK LANGUAGE ……… 66

4.1.1.7 Compliment- Acceptance/Rejection ……… 97

4.1.1.8 Complaint-rejection ……… 101

4.1.2 Turn-Taking in TB Conversation ……… 106

4.1.2.1 Completion Points ……… 111

4.1.2.1.1 Grammatical Completion Point ……… 111

4.1.2.1.2 Intonational Completion Point ……… 116

4.1.2.1.3 Semantic Completion Point ……… 120

4.1.2.2 Turn Allocation Component ……… 129

4.1.2.2.1 Current Speaker Selects Next ……… 131

4.1.2.5.3 Self-initiated, Other-repair ……… 168

4.1.2.5.4 Other-initiated, Other Repair ……… 170

4.2 Findings ……… 173

4.2.1 Introductory Remarks ……… 173

4.2.2 Negative Cases as new findings ……… 179

4.3 Discussion ……… 186

4.3.1 System Constraint ……… 187

4.3.1.1 Question-answer, Greeting-greeting, Summon-answer 187 4.3.1.2 Offer-Acceptance/Refusal, Invitation-Acceptance/Rejection 191 4.3.1.3 Accusation-denial, Compliment-Acceptance/Rejection, Complaint-Rejection ……… 195

4.3.1.4 TCU and TRP, Completion Point ……… 198

4.3.1.5 Turn Allocation, Repair, Overlapping Talk, Silence …… 201

4.3.2 Ritual Constrain ……… 207

4.3.2.1 Question-answer, Greeting-Greeting, Summon-Answer 207 4.3.2.2 Offer-Acceptance/Rejection, Invitation-Acceptance/ Rejection ……… 212

4.3.2.3 Accusation, Compliment, Complaint ……… 214

CHAPTER V CONCLUSIONS AND SUGGESTIONS ……… 223

5.1. Conclusions ……… 223

5.2 Suggestions ……… 227

REFERENCES …………..……….. 229

ABSTRACT

This disertation focuses on Conversation Analysis (CA) regarding the structure of Adjecancy Pair (AP) and Turn-Taking in Toba Batak (TB) conversations. The aims of the research are to explain: a) how the AP of TB conversation operates, b) how the end of turn is grammatically, intonationally, and semantically projected, and c) how the Turn-Taking in TB conversation operates. The main theory used is CA theory by Sacks, Schegloff, and Jefferson (1974). This theory assumes that there are four basic assumptions in conversation, they are: a) conversation is structurally organized, b) conversation is jointly produced among participants, c) conversation is contextual, and d) conversation is locally managed. Since conversation is structurally organized and sequentially constrained, there can be found structural approach, that is, adjacency pairs. This exemplifies structural organization as well as orderly sequence of interaction in conversation. Adjacency pairs give slot to the next position whether responded or not. When the first is not responded, the second would be noticeably absent, that leads to a repair actions. As the joint production among participants, recipients show his or her intersubjectivity as the understanding and inferences of the the speaker’s utterance. Again, when recipients do not show his or her intersubjectivity, the speaker may reply with repair work in the next slot, which is called the third position repair. Since conversation is locally managed, it implies that turn-by-turn organization of conversation are analyzed.

The research was conducted using qualitative method. The data were collected based on audio recording and video recording of mundane conversation or casual talk which constitute fifty texts of conversations. These texts are categorized into two, they are forty texts dealing with Adjecancy Pair and ten texts dealing with Turn-Taking. The analysis is based on CA, that is sequential analysis.

silence occurs in lapse, 16) The ends of turn which are grammatically, intonationally, and semantically projected occur in TB conversation, 17) The rules of Turn-Taking and the organization such as silence, overlapping talk, and repair are applicable in TB conversation, 18) Turn-taking are not culturally bound.

The findings imply that learning the adjacency pairs of foreign language can not depend only on the mechanical structure, but on the ritual constraint, and this is also effective in the first language (TB). On the other hand, there is a room for turn-taking to be further studied based on ritual constraint.

It is concluded that there are negative cases in AP and turn-taking of TB.

ABSTRAK

Disertasi ini berfokus pada analisis percakapan yang mengkaji struktur pasangan berdekatan dan gilir berbicara dalam percakapan bahasa Batak Toba. Tujuan penelitian ini adalah untuk memerikan: a) bagaimana pasangan berdekatan dalam percakapan bahasa Batak Toba dipraktekkan, b) bagaimana akhir gilir bicara diproyeksikan secara gramatikal, intonasional, dan semantikal, dan c) bagaimana gilir bicara dalam percakapan bahasa Batak Toba (PBBT) dipraktekkan. Teori utama yang digunakan dalam penelitian ini adalah teori analisis percakapan oleh Sacks, Schegloff, dan Jefferson (1974). Terdapat 4 asumsi dasar dalam percakapan berdasarkan teori ini: a) percakapan terorganisasikan secara struktur, b) percakapan merupakan hasil produksi sesama partisipan, c) percakapan kontekstual, dan d) percakapan di kelola secara lokal. Karena percakapan itu terorganisir secara struktur dan dihadapkan pada urutan (sequence), maka ditemukan suatu pendekatan struktur yang disebut sebagai pasangan berdekatan. Ini menunjukkan organisasi struktur serta urutan interaksi yang teratur dalam percakapan. Pasangan berdekatan memberikan tempat kepada posisi/urutan berikutnya yang dapat direspon maupun tidak. Apabila yang pertama tidak direspon, yang kedua dapat dipertanggung jawabkan dan menimbulkan tindakan perbaikan. Sebagai produksi sesama partisipan, pendengar akan menunjukkan keterlibatannya karena mengerti ujaran pembicara. Apabila pendengar tidak menunjukkan keterlibatannya, pembicara akan melakukan tindakan perbaikan pada tempat berikutnya, yang disebut dengan perbaikan pada posisi ketiga. Karena percakapan dikelola secara lokal, hal ini mengimplikasikan adanya analisis giliran per giliran dalam percakapan.

Penelitian ini dilakukan dengan menggunakan metoda kualitatif. Data dikumpulkan dengan merekam secara audio dan video melalui percakapan kasual. Data yang dianalisis ada 50 data yang terdiri dari 2 bagian: 40 data digunakan untuk menganalis pasangan berdekatan, dan 10 data digunakan untuk menganalisis gilir bicara. Data dianalisis berdasarkan analisis percakapan, yaitu analisis sekuensial.

undangan mencakup tiga sekuen: perluasan awal, perluasan akhir, dan sekuen sisipan, 9) Pasangan tawaran dan undangan adalah berhubungan, 10) Pasangan tuduhan memiliki respon penolakan pada pasangan kedua sebagai yang diinginkan, 11) Pasangan pujian mempunyai respon penolakan yang dihaluskan pada pasangan kedua, 12) Pasangan keluhan mempunyai respon penolakan pada pasangan kedua sebagai yang diinginkan, diformulasikan dalam bentuk ketidakberpihakan, 13) Pasangan tuduhan, pujian, dan keluhan adalah berhubungan, 14) Kaidah pertama gilir-bicara (pembicara sekarang memilih pembicara berikut) tidak selalu dapat diaplikasikan dalam percakapan bahasa Batak Toba, 15) Kesenyapan panjang terjadi dalam percakapan yang terhenti sementara, 16) Akhir dari giliran yang diproyeksikan secara gramatikal, intonasional, dan semantikal terjadi dalam percakapan bahasa Batak Toba, 17) Kaidah gilir bicara dan organisasi seperti kesenyapan, percakapan tumpang tindih dan perbaikan dapat diaplikasikan dalam bahasa Batak Toba, 18) Gilir bicara tidak terikat secara kultural.

Implikasi temuan ini adalah bahwa belajar pasangan berdekatan bahasa asing dan bahasa pertama tidak dapat hanya tergantung pada struktur mekanis, tetapi juga harus tergantung pada hambatan ritual. Pada sisi lain, terbuka wacana untuk mengkaji gilir bicara berdasarkan hambatan ritual.

Dapat disimpulkan bahwa, terdapat kasus-kasus negatif yang menjadi temuan pada penelitian ini.

CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION

1.1. The Background of the Study

The first motivation of this study stems from the problematic issue occurred in

English teaching of conversation for the homogenous students of Toba Batak (TB)

and in a TB interaction in a coffee-counter. When it was observed, the students in

responding the compliment of the other did not practise them as applied in English

conversation. A case in point is reflected in this extract:

A : You have a nice shirt! B : No, it is my old one.

From the above conversation, A’s compliment was rejected by B. It is not the

case in English conversation where compliment is not rejected, A’s compliment is

accepted in English conversation by an appreciation response such as, thank you.

Another case in point deals with a TB conversation of more than two

participants in the coffee-counter. It was noted that there is no regularity in terms of

the turn-taking among the interactants. The taking of turn and transition from one

speaker to another are haphazard. There are problems of turn-taking management in

such a conversation.

About conversation, Furo (2001:24) presented four asumptions in

produced among participants, 3) conversation is contextual, and 4) conversation is

locally managed. These asumptions indicate there are structures and process of

turn-taking in conversation as well as units that build the turn-turn-taking.

The second motivation of this study is derived from the statement: “there has

been a considerable shift in emphasis in linguistic research from phonology and

morphology to syntax and semantics and from there on to an increased interest in the

study of language in social context” (Platt and Platt 1975 : 1). There are two shifts of

linguistic research in the quotation above, i.e., the one from phonology and

morphology to syntax and semantics, and another one from syntax and semantics to

study of language in social context. The study of language in social context or in a

more specific term, a function - based study (Halliday,1994) was less emphasized than

the formal study of language.

Like Indonesian language, according to Sinar (1998 : 1), much of the study

done was centered on the formal aspect of the language. The trend is also true for the

study of the regional languages, such as that of the Toba Batak Language (TBL), in

other words, there has not been a concern with the language function or language use

especially in conversation, as what is going to be investigated in this study. The

available studies are mostly dealing with syntax, semantics, and morphology of TBL.

This study is a compromise one where there is a combination of formal and

functional aspect in the study of TBL. The functional aspect such as interactional

units: turn – taking, adjacency pairs, preference, silence, overlapping talk, and repair

properties: grammatical, intonational, and semantic properties are also studied, so that

the relationship between language and interaction can be explained in Toba Batak

Conversation.

A study on the structure of discourse involves examining utterances from both

linguistic and interactional view points since utterances are realizations of language in

use. In this case, one should begin with how particular units (utterances, actions) are

used and draw conclusion about the broader functions of such units from functional

analysis. In other words, “one would begin from observation and description of an

utterance itself, and then try to infer from analysis of that utterance and its context

what functions are being served”, (Schiffrin, 1994).

As this study focuses on the conversations in TBL, utterances would be the

basic unit of analysis which are viewed from formal and functional aspect of

categories. From formal view, three linguistic units (grammatical, intonational,

semantic) are examined to see the construction component, whether the grammatical,

intonational, and semantic completion point influence the speaker changes or

transition relevance places (TRPs). From the functional view, interactional units such

turn–taking, adjacency pairs, preferences, are examined to see the distribution

component.

One of the approaches in analyzing conversation is conversation analysis (CA),

which emerged in the pioneering researches of Harvey Sacks (Hutchby, 1998: 5) into

discovered some subtle ways in which callers to a suicide prevention center managed

to avoid giving their names, as shown in the conversation below :

A : This is Mr. Smith, may I help you?

B : I can’t hear you.

A : This is Mr. Smith.

B : Smith.

Sacks (Hutchby and Woffit, 1999:18) had observed that in the majority of cases if the

person is taking the call within the organization started off by giving their name, then

the suicidal person who was calling would be likely to give their name in reply. But in

one particular call, He noticed that the caller (B) as shown in the conversation above

seemed to be having trouble with the name of the answerer. Then the agent who took

the call found it difficult to get the caller’s name. For him, the avoidance of giving

one’s name in the conversation by answering “ I can’t hear you” leads to the

accomplishment of action or particular things given by an utterance. So, in this case

the utterance is an action.

However, Sacks (Hutchby and Woffit, 1998:8) here emphasizes that “I can’t

hear you” is not always an expression representing the way one avoids giving his

name. Rather he viewed the utterance as an action which is situated within specific

context. He also observed that by the caller’s “not hearing”, he is able to set up a

sequential trajectory in which the agent finds less opportunity to establish the caller’s

name without explicitly asking for it. Thereby the caller is able to begin the

Utterance as an action is also supported by Schegloff (2007: 1) as he focused

on action rather than a topic in talk-in interaction. An utterance like “Would

somebody like some more ice tea?” is better understood as “doing an offer” than as

“about ice tea”.

Conversation Analysis is derived from Ethnomethodology which is focused on

the methods by which the group conducts coversation. Group here refers to society’s

members which are considered having intersubjectivity and cammon-sense knowledge

realized in talk-in interaction in their daily life. Obviously, the member’s knowledge

meant by this method concerns with the member’s knowledge of their ordinary affairs,

knowledge that shows a sense of order in everyday conduct, and this is publicly

displayed in activity which is going on.

Austin and Searle (Schiffrin, 1994 : 6 ) developed speech act theory from the

basic insight that language is use, not just to describe the world, but it can perform an

action. The utterance “I promise to be there tomorrow” performs the act of

promising,and the utterance “The grass is green” performs the act of asserting. An

utterance can also perform more than one action as shown below.

Speaker : Can you pass the salt?

Hearer : / pass the salt/

The first action is an act of questioning the ability of the hearer, and the second

performs an act of requesting. This is what distinguishes utterance from sentence. In

neither a physical event nor a physical object, it is conceived of abstractly as a string

of words put together by the grammatical rules of a language.

Of Sacks’ observation on talk-in interaction (Hutchby et.al, 1999), he really

based his analysis on the naturally occurring data from which he did a turn by turn

details of the conversation so that a robust analytical basis would be used to get a

robust finding. What he observed then leads to the key insights which are treated on

the methodological basis for conversation analysis. These key insights can be

summarized below :

1. Talk – in interaction is systematically organized and deeply ordered.

2. The production of talk – in interaction is methodic.

3. The analysis of talk- in interaction should be based on naturally occurring data.

4. Analysis should not be constrained by prior theoretical assumption.

How then language is related with interaction? Ford and Thompson (1996)

observed grammatical, intonational, and semantic completion point. There are three

criteria in identifying grammatical completion point : well-formed clauses,

increments, and recoverable predicates. The verb put in this sentence ; I put the book

on the desk, projects a possible syntactic completion point which is after an argument

of a place. Because the verb put is a two place predicate (Haegemen, 1993 :39) and

takes two arguments, a direct object the book, and a place on the desk, and considered

as a well – formed clause, a grammatical completion point is marked after

prepositional phrase on the desk. However, I put the book , is not a well-formed

“Words and phrases that appear after the first grammatical completion point are

considered increment”(Furo, 2001:12). A grammatical completion point in sentence :

I bought the book yesterday is marked after the noun phrase the book as well as after

the adverb yesterday. Since the sentence I bought the book is well – formed, it is

considered grammatically complete. I bought the book yesterday is also a well –

formed clause, and the adverb yesterday is considered increment. So, another

grammatical point is marked after yesterday. In this way, grammatical completion

point is marked incremently after a well – formed clause.Recoverable predicates, that

is, the understood predicates that can be taken from the context are considered to form

complete clause. An example of recoverable predicate is answer to question, as seen

in this question : Where did you go last week?, the answer is ; to Jakarta. Although

the answer does not have a predicate, it is assumed to be completed from the context,

(I went) to Jakarta. A grammatical completion point is therefore marked after the

noun Jakarta.

Intonational completion point is determined by falling intonation designated by

period, and rising intonation designated by question mark. The sentence, He is a

doctor, has a falling intonation contour as found generally in positive statements, and

it is designated by period. This period characterizes the intonational completion point.

A rising intonation contour is commonly found in yes – no questions, such in

sentence : Are you a teacher? The question mark characterizes the intonational

Semantic completion point refers to floor right, floor-claiming utterance,

proposition, and reactive token. When the speaker has the right or obligation to hold

the floor, a semantic completion point is marked at the point where the right is

expired. This can be obtained by the speaker’s status (e.g. moderator) or obtained in

the course of interaction (e.g. the speaker who is asked a question) and thus selected

as the next speaker.

In floor-claiming utterance, when a longer turn is determined by words,

phrases, or preliminary action, or negotiated by interlocutor, a semantic completion

point is marked at the end of the projected longer talk. And when the longer talk is

finished, it is considered semantic completion point. When there is no such semantic

indication that projects the upcoming longer talk, semantic completion points are

designated at the end of the proposition, as in : I assumed that he is a good cook.

Reactive tokens are considered semantically complete, although they do not

have the full structure of a sentence. There are six categories of them :

1. Backchannel : um, uh

2. Reactive expression : great!

3. Repetition : He was funny

Was he funny?

4. Collaborative finish : A : more like a brunch

B : brunch

5. Laughter : hahaha

Sociolinguistics also concerns with language use in social interaction. In line

with this, examining the speech activities of social groups casts light on the conditions,

values, beliefs as well as the social order of the group. TBL can also be examined in

terms of speech activities as to find out what are there reflected in the social

interaction. In the context of Toba Batak conversation whether instituonally or daily

spoken, the success of talking is much depending on the individual’s verbal skill, as

this is central epecially in custom (adat) intraction. As what needs to be a means of

solution to the problems emerge in cultural activities is the ability to use the spoken

language in social interation. In marhusip (wishpering talk), a speaker who is skilled in

Toba Batak interaction will start to say to the audience (hearer) :

“ipe nuaeng bere….., porsea do hami di hatani ama ni anu nangkin, alai asa umpos roha nami denggan do paboaonmu manang naung sian roham do naeng manopot boru nami. jala asa tangkas botoon nami laos paboa ma jolo hira ise ma nuaeng lae na tumubuhon hamu, sian huta dia jala anak paipiga ma ho anak ni lae? (Simbolon, 1981: 15).

The equivalent English would read as the following:

now guy, we believe what we heard from the people. but to be more comfortable, please tell us if you really want to marry our daughter. to be precisely, let us know your personal family and social background.

The hearer who represents the guy will respond the question in more polite way

in order that the speaker would convince the guy to be the only person that will

propose their daughter. To be more successful in such an interaction the hearer as one

of the participants must understand his social role and the other role, as to fix what he

A description of all factors that are relevant in understanding how particular

comunicative even achieves its objectives was given by Hymes (1974) in his

SPEAKING formula, in which S refers to setting and scene, P stands for participant, E

for Ends, A is an act seqeunce, K is key, I refers to instruments, N is the norms of

interactions, and G stands for genre.

Setting deals with the palce and time (the concrete physical condition in which

speech takes places), while scene is the cultural definitions of the occasions.

Participants are combinations of speakers and listeners, addressors and addressee, or

senders and receivers. End concerns with the expected outcome of exchange as well as

with the pesonal goals that particpant seek to accomplish on particular accasions. Act

sequence refers to the actual form and content of what is said. Key refers to the tone,

manner of spirt in which a particular message is conveyed. Instruments deals with the

spesific behavior attached to speaking. Genre refers to types of utterance; poems,

provebs, riddles, sermons, etc.

The eight factors in speech potentially influence the success of speakers in talk.

These factors, especially the cultural ones, are used to see whether they can influence

the tructure of Toba Batak conversation, the interactions structure and the linguistc

structure, for both conversation in institutional and ordinary setting. In this research,

the focus is on the ordinary talk. The cultural factors have to do with ritual constraints.

Obviously it is looming from the discussions above there are four important

aspects underlying this research. Based on the langage use, conversation analysis

One that distinguishes CA from other appoaches that focused language use or function,

one of them is speech act, is that CA used naturally occuring data in its analysis.

Second, langauage is action, and realized in utterances, it is necessary to

scrutinize the action through the turn-taking and adjacency pairs in Toba Batak

conversation, so that the interaction among speakers and listeners can be accounted,

and the interaction structure of Toba Batak conversation can be explained.

Third, based on the language view, it is crucial to examine the lingustic

propeties like grammatical, intonation, and semantic completion point in the TB

conversation, because these properties can relate language with interaction in the

domain of transation relevance place (TRP).

Fourth, cultural factors in terms of ritual constraints play an important role in

social interaction, so influencing the structure of conversation interactionally,

especially the adjacency pairs, and in terms of system constraints which are not

cultural bound.

1.2 Research Problems

As the research focuses on conversation analysis of TBL, two of the four basic

assumptions on conversation are the point of departure to discuss what problems

emerge in conversation (Furo, 2001: 27). The first problem deals with the structure of

conversation, as the first assumption is that conversation is structurally organized, so

managed. If it is locally managed, it is done turn-by-turn analysis which is realized in

constructing turn construction units, turn distribution components and turn-taking

organization such as, silence, overlapping talk and repair. Turn Construction Units

(TCUs) are linguistic units like sentences, clauses, words, etc, in which at their end

there are linguistic completion points which ifluence interaction as at these ends it is

possible a transition from one speaker to another occurs. If this occurs, rules of turn

taking follows, and such other turn organizations can occur. Are all these problems

applicable in TB conversation?

Based on the previous decription and the question above, the problems of

research in this study are formulated on three questions as the following.

1. What are the interaction structures ( Adjacency Pairs) in TB conversation?

2. How are the ends of turn in TB conversation grammatically, intonationally,

and semantically projected?

3. How does the turn-taking of TB conversation operate?

1.3 The Objectives of the Study

This study examines the interaction structures of the TB conversation and the

linguistic structures involved in TRP. When the interaction structures are analyzed in

terms of conversation analysis, the most basic unit of the interaction is adjacency pair,

the other unit is turn-taking. When language is used in interaction, linguistic

changes or transtion relevance places. Thus, the objectives of this study are to describe

the applicability of adjacency pairs, turn-taking (Sacks, Schegloff and Jefferson 1974),

and the applicability of completion points (grammatical, intonational, and semantic )

as in the TB conversations . Specifically, the objectives are :

(1) to examine the structures of adjacency pairs in TB conversations.

(2) to examine how the end of turn, grammatically, intonationnally, and

semantically are projected.

(3) to discuss how the turn-taking of TB conversations operates.

1.4 The Significance of Research

Examining adjacency pairs and turn-taking in the TB conversation is benificial

in two respects. First, we can recognize how the first pair part as component of

adjacency pair varies in the TB conversations. For Example, is greeting in Toba Batak

always followed by greeting? Secondly, one can describe how the turn taking system

in Toba Batak operate can be understood by examining the turn distribution

component. For example, does the current speaker select the next speaker, or the next

speaker applies the self select or the current speaker continues?

Analyzing the linguistic properties that can influence the interaction in the TB

conversation can construct the relation between language and interaction ;

grammatical, intonational, and semantic can project the end of a turn, so makes it

Practically the research findings can be made as a reference for teachers who

teach English conversation to homogenous students like that of Toba Batak.

1.5 The Scope of Research

As has been stated in the previous section, this study is examining the

interaction structures of Toba Batak conversation and the linguistic structures that

influence the interaction in the TB conversation.

The interaction structures in this study can be limited to adjacency pairs and

turn-taking. In adjacency pairs, two parts will be analyzed as their components, the

first pair part and the second pair part. In English, there is a greeting in the first part

and also greeting in the second pairs part like in :

A : Morning

B : Morning

Preferences is also a part of adjacency pair which are shown in invitation. The

response of invitation can be positive as reffering to preference and negative as

referring to dispreferences. So first pair part , second pair part, and preference would

be under discussion in adjacency pair.

The component of turn-taking such as, turn construction units, turn distribution

component, silence, overlapping talk, and repair are analyzed in Toba Batak

Conversation. Here, it will be examinined to what extent turn-taking proposed by

Sacks, Schegloff, and Jefferson (1974) are applicable to the different phenomena such

The elements of linguistic structure to be examined are grammatical,

intonational, and semantic units, as those which are realized in grammatical,

intonational, and semantic completion point related to transition relevance place in

turn-taking. So, the turn constructional unit is not included in interactional structure.

1.6 The Definitions of Key Terms

There are some key terms that should be defined in this study such as:

interaction structure, linguistic structure, conversation, Toba Batak conversation,

adjacency pairs, turn taking and utterances.

Interaction or conversational structures refer to adjacency pairs and turn-taking

in conversation (Tracy, 2002: 113). Lingustic structure comprises properties or units

like grammatical, intonational, and semantic units. In this study, these properties refers

to completion point which can influence the speaker changes (Ford and Thompson,

1996).

Conversation is defined as the spontaneous talk in interactions among two or

more participants in casual, informal setting of everyday life. In relation to this,

admittedly, the TB conversation is one which is used in the TB language of everyday

life.

Adjacency pairs which constitute successive uttreances by different speakers

A turn is the talk of one party bounded by the talk of the moment is changed. In

this case, the overlapping talk and silence can be problem, but they are considered as

structures of talk.

Utterances are units of language production that are inherently contextualized.

Defining discourse as utterances seems to balances both the functional emphasis on

CHAPTER II

REVIEW OF LITERATURE

This chapter is aimed at reviewing the literature of items which are the most

relevant to the study such as, relevant approaches to analyzing conversation,

conversation which consists of characteristic and assumption, adjacency pairs, turn,

turn taking, TB culture and language as well as previous studies.

2.1 Relevant Approaches To Analyzing Conversation

There have been various perspectives in analyzing conversation as the spoken

interaction in everyday life. Eggins and Slade (1997:23) present five persepective such

as ethnomethodology, sociolinguistic, logico-philosophic, structural-functional, and

social-semiotic. From Ethnomethodology point of view, an approach called

Conversation Analysis (CA) has been proposed as a part of discourse study as what the

others have. Sociolinguistic-based refers to three approaches, Ethnography of

Speaking, Interactioanal Sociolinguistic, and Variotion Theory. Logico-philosophic

deals with Speech Act Theory and Pragmatics. Structural-functional embodies two

approaches like Birmingham School and Systemic Functional Linguistics, and

Social-semiotic consist of Critical Discourse Analysis.

As this study deals with conversation Analysis, it is discussed firstly before the

2.1.1 Conversation Analysis

As a matter of fact, Conversation Analysis derived from Ethnomethodology.

According to Schiffin (1994:233), Garfinkel’s term “ethnomethodology” was modeled

after terms used in cross-culture analyses of ways of “doing” and “knowing”.

Ethnobotany, for example, is concerned with culturally specific systems by which

people “know about” (classify, label, etc) plants. The term “ethno” seemed to refer to

the availability to a member of common-sense knowledge. It is the ordinary

arrangement of a set of located practices. In other words, ethnomethodology concerns

with “a member’s knowledge of his ordinary affairs, of his own organized enterprises,

where that knowledge is treated by us as part of the same setting that is also makes

orderable. So uncovering what we know is a central concern for ethnomethodology.

For this, knowledge and action are deeply linked and mutually constitutive, which is an

important bearing on the study of language.

In the study of talk, ethnomethodology means an insistence on the use of

materials collected from naturally occuring occasions of everyday interaction. Eggins

and Slade (1994:25), stated that Conversation Analysis (CA) focused on conversation

because it offers a particulary appropriate and accessible resource for

ethnomethodology enquiry. Sharrock and Anderson (In Eggins and Slade, 1994:25)

further stated that “Seeing the sense of ordinary activities means being able to see what

people are doing and saying, and therefore one place in which one might begin to see

how making sense is done in terms of understanding of everyday talk”. In relation with

turn-taking. In conversation, speaker keep taking turns, and in the process of keeping turns,

a speaker has to be able to see the point when transfer of role is possible. This is done

by Turn Construction Units (TCU’s), units constructed to signal turn transfer. These

units are realized in grammatical units considered as the end of turn cannot always

determine who would be the next speaker. For this, Sacks et al. (1974) note that at the

end of TCU there are two possibilities of determining the allocation of turns. First, the

current speaker selects the next speaker. Second, if the current speaker does not select

the next speaker, the speaker may self-select. Sacks and Schegloff explained a concept

to explain the ordeliness of conversation, that is, adjacency pairs, a main format in

which talk is sequenced. Adjacency pairs is a sequence of two utterances which are

adjacent, produced by different speakers, ordered as a first part and second part, and

typed, so that the first part requires a particular second part. The common adjacency

part is question/answer sequence. The others are: request/grant, offer/accepted,

affer/reject, etc.

2.1.2 Ethnography of Speaking

The ethnography of speaking or communication is an approach to discourse that

is based on anthropology as critic of Dell Hymes to Chomsky’s well known

refocussing of linguistic theory on the explanation of competence –the tacit knowledge

of the abstract rules of language. According to Hymes (1974) communicative

directly governed by rules or norms for the use of speech. It includes interaction such

as a conversation at a party, ordering a meal, etc. However, the notion of

communication cannot be assumed to be constant across culture. Cultural conceptions

of communication are deeply intertwined with conception of person, cultural values,

and world knowledge, such that instances of communication behavior are never free of

the cultural belief and action system in which they occur. Hymes explained different

components of communication used to understand the social context of linguistic

interactions, in a grid known as SPEAKING (as has been explained in chapter one).

2.1.3 Interactional Sociolinguistics

The approach to discourse called interaction Sociolinguistics stems from

anthropology, sociology, and linguistics, and shares the concerns of all three fields with

culture, society, and language. This approach was inspired by Gumperz (1982) and

Goffman (1959) which was discuused by Eggins and Slade (1997:34). Gumperz

focuses on how people from different cultures may share grammatical knowledge of a

language, but differenly contextualize what is said such that very different messages

are produced. He demonstrated that interactants from different socio-cultural

backgrounds may hear and understand discourse differently according to their

interpretation of contextualization cues in discourse. Gumperz describes a number of

problems that have arisen between Indian English speakers and British English speaker.

For instance, Indian English-speaking women working in a cafetaria were getting

their conversatinal action, Gumperz dicovered that the British English patrons were

atributing rudeness to the staff because of the workers’ intonation patterns when they

offered service. Instead of saying “Gravy” with a rising intonation, as British English

speakers would to offer a service and be polite, the Indian Speaker were saying

“Gravy” with a falling intonation. For British English speakers, this conveyed an

identity message the suggested you are not important, so just take it or leave it.

Whereas Goffman focuses on how language is situated in particular

circumstance of social life, and how it adds (or reflects) different types of meaning and

structure to those circumstances. For Example, communicators may consciously work

to created certain impression or may do inadvertently. Goffman describes this as the

differences between meanings that itentionally given and those that are given off. A

person speaking to a group may work to present, telling a joke to get started, and so on.

On the other hand, if in speaking her voice cracks or she pauses just after a few words,

people will consider her as nervous. This is categorized as meaning that was given off.

2.1.4 Variation Theory

A variation approach to discourse stems from linguistic variation and change.

An important part of thre variationist approach to discourse is the discovery of formal

patterns in text (narratives). This theory was initially developed by Labov (1972), (in

Eggins and Slade, 1997), the majority of his analyzing the work on the structure of text

personal experience. This involves in six stages: Abstarct, Orientation, Complication,

Evaluation, Resolution, and Coda (see further Eggins and Slade, 1997:39).

2.1.5 Speech Act Theory

Speech act theory was developed by John Austin (1962) and John Searle

(1969), in Eggins and Slade (1997), from basic insight that language is used not just to

describe the world as been discussed previouly, but to perform a range of other actions

that can be indicated in the performance of the utterances itself. They call this as the

illocutionary force of an utterance. As example, the following utterances in Toba Batak

contex indicate a performance of forbidding:

A : Sian dia ho Tiur? (Where have you been?)

B : (Keep silent and immediately entering her room)

As seen from the example that A (father) asked B (daughter) the place where

she was from. B actually should have answered by naming the place she is from, but

she just kept silent and immediately came into her room. She understood that her father

was not just asking her but more than that, her father did not allow her to be outside at

midnight. So the utterances above can be understood as both a question and a

forbidding.

2.1.6 Pragmatics

A pragmatic approach to discourse is based primarily on the philosophical ideas

different types of meaning and argued that general maxims of cooperation provide

inferential routes to speaker’s communicative intention. He further developed some

maxims which are implicative in cooperative principle. These maxims are: maxim of

quality (say only the required quantity), maxim of quality (say honestly), maxim of

relevant (be relevant), and maxim of manner (be brief, not being ambiguous).

In describing conversation as cooperative, Grice did not mean to say that

conversation is only and always nice and pleasant. Conversation is a cooperative

activity in much the same way as football-playing. So, cooperative pribciples are not

obligatory in that they are not attached to rules.

2.1.7 Birmingham School

This approach according to Eggins and Slade (1997) was established through

the work of Sinclair and Coulthard (1975). Eggins and Slade (1994:44) say that it

derived from socio-semantic linguistic theory of J.R. Firth (1957), particulary as

developed by Halliday in the early description of scale-and-category grammar. The

Birmingham School focus on discourse structure, whereas Halliday oriented in

semiotic from the systematic perspective. Birmingham School distinguishes discorse as

a level of language organization from grammar and phonology. Distinct discourse unit

were indentified for analysis of interactive talk in terms of rank. The units are made of

one or more of the units immediately below it. In classroom discourse study, Sinclair

Transactions, and finally make up Lesson to be the largest units in teaching discourse.

The Birmingham school present such conversational structure in pedagogic context in

three moves: Initiation, Response and Feedback.

2.1.8 Systemic Functional Linguistics

Systemic functional linguistics is an approach developed by Halliday (1973),

(in Eggins and Slade, 1997) which is based on the model of language as Social

Semiotic to which it is elaborated to a functional-semantic interpretation of

conversation. Systemic approach offers major benefits in conversational analysis: 1) it

offers an integrated, comprehensive and systematic model of language which enables

conversational patterns to be described and quantified at different levels and in

different digree of detail, 2) It theorizes the links between language and social life so

that conversation can be approached as a way of doing social life. More specifically,

casual conversation can be analysed as involving different linguistic patterns which

both enact and construct dimensions of social identity and interpersonal relations

(Eggins, 1997:47).

Halliday (1994) states that in a casual conversation there are simultaneously

embedded three types of meaning; ideatioanal meaning, interpersonal meaning, and

textual meaning. Ideational meaning concern with the topic being talked about, when,

by whom, and how topic transition and closure is achieved. Interpersonal meaning

focused om what kinds of role relation are established through talk, what attitudes

how they negotiate to take turns. Textual meaning refers to different types of cohesion

used to tie chuncks of the talk together.

In contextual respect, Eggins and Slade (1997) related three types of meaning to

register. Ideational meaning is related to Field, interpersonal meaning to Tenor and

textual meaning to Mode. Genre is also included as a further level of context in

analyzing conversations.

2.1.9 Critical Discourse Analysis

In this approach, Fairclough (1995), (in Eggins and Slade,1997) studies the

relationship between language, ideology and power as well as between discourse and

sociocultural change. The contribution of this approach are realized in three main areas:

notions of text and difference, methods and techniques of conversation anlysis, and

critical account of genre.

Kress (1985), (in Eggins and Salde, 1997) explained it is differences that

motivate speech, as Argument to differences is of an ideological kind, interview to

differences arround power and knowledge, Gossip to differences around informal

knowledge, Lecture to differences arround formal knowledge. Kress argued that

individuals who come to interaction share membership of particular social groupings,

and learn modes of speaking or discourse associated with those institutions.

In critical discourse analysis, the micro-event and the macro-social structures

impression of ordeliness in interaction. Ordeliness arises from participants conformity

with their background knowledge about the norms, right and obligation appropriate in

interaction in particular context. As an example, a lecture in university is orderly, as

the lecturer and the students are in conformity to dominant discourse practice whereby

the lecture talks without invitation and the students listen without complaint.

2.2 Conversation

This part talks about the characteristic of conversation as well as the assumption

used in conversation. Here the characteristic of conversation deals with the strength of

mundane conversation used as data in conversation on Sack, Schegloff, and Jefferson

study (in Furo, 2001).

2.2.1 Characteristic of Conversation

As has been defined before that conversation is spontaneous talk in interaction

among two or more participants in casual, informal settings of everyday life (Furo,

2001:25). This kind of conversation has also been touched by Goodwin and Heritage

(1990) as ordinary and mundane conversation. Whereas listeners freely alternate in

speaking, and this occurs in informal setting. By those definitions we can direcly

distinguish it from a talk that takes institutional setting as its context. For example, a

conversation which occurs in a debate , seminar, adat ceremony, all of which the

In ordinary conversation or casual talk, there is no an arrangement who, where,

and when to talk. All come spontaneously. Eventhough ordinary, and the general

impression is that it is chaotic and disorderly, it is useful for conversation analysis

which is based their work on ethnomethodological enquire.

Seeing the sense of ordinary activities means being able to see what people are

doing and saying, and therefore one place in which one might begin to see how making

sense is done in terms of the understanding of everyday talk (Sharrock and Anderson

in Eggin and Slade, 1997:25).

When there was an invention of recording devices, and the willingness to study

mundane conversation in depth, what people doing and saying in their everyday talk

are actually highly organized and ordered.

According to Furo (2001) conversation treated as data in conversation analysis

has three characteristic :

1. It reflected the communicative competence of the participant.

2. It is the most unmarked form of communication.

3. It reflected the interaction norms as well as the social system of the culture

where it occurs.

This communicative competence (Schiffrin in Furo, 2001) constitutes our tacit

knowledge of the abstarct rules of language, which is required both to produce

sound/meaning correspondences betweexn sounds, meaning formed in socially and

linguistic and pragmatic ability, or show the way participants use language in

interaction.

As the most unmarked form of communication, conversation can be treated as

the prototype of other forms of talk. Goodwin and Heritage (1990: 284) observed that

ordinary conversation is the point of departure of more specialized communicative

context. As it occurs in ubiquity, ordinary conversation has been familiar with the life

of Toba Batak. At this present time only talks in institutional setting, such as

conversation in adat ceremony has been under investigation. Of its mundane nature,

ordinary conversation may involve all people from all ranks, whereas instituonal talks

take limited participants, like only the married participants can participate in the

conversation.

As conversation carried out in cultural and social context, the action done can

reflect the identity of participants including interaction norms on social process in

interpersonal relationships (Schiffirin, 1994). In this case, conversation can indicate the

basic principles that govern the linguistic and non-linguistic behavior of the members

of the society in which the principles are constituted.

2.2.2 Assumption in Conversation

The four basic assumptions in conversation as discussed in chapter one (Furo,

2001: 24) are:

1. Conversation is structurally organized.

3. Conversation is contextual

4. Conversation is locally managed.

Since conversation is structurally organized and sequetially constrained

(Goodwin and Heritage, 1990), there can be found structural approach, that is,

adjacency pairs. This exemplifies structural organization as well as orderly sequence of

interaction in conversation. Adjacency pairs give slot to the next position whether

responded or not. When the first is not responded, the second would be noticeably

absent, that leads to a repair actions.

As the joint production among participant, recipients show his or her

intersubjective as the understanding and inferences of the the speaker’s utterance.

Again, when recipients do not show his or her intersubjectivity, the speaker may reply

with repair work in the next slot, which is called the third position repair (Schegloff in

Furo, 2001).

Conversation is context dependent. This assumption means that conversation is

shaped in context, the prior context shaped) and the new context

(context-renewing). In this way, context does not refer to social one such as participants’

identities or situational settings but they are sequences of action and interpretation that

emerge in the organization of conversation (Goodwin and Heritage, 1990)

The fourth assumption conversation is locally managed, implies that

turn-by-turn organization of conversation are analyzed. These occur in the turn-by-turn-taking as

exchanges are systematically relaized with minimal gap and overlap because speakers

take transisition relevance place (TRPs).

2.3 Adjacency Pairs

We have noted above that structural view in interaction is related to adjecency

pairs. That is a sequence of two utterances which are adjecent, produced by different

speakers, ordered as a first pair part and second part, and typed, so that a first part

requires a particular second part (Schegloff and Sacks in Schiffrin, 1994).

According to Tracy (2002:114) there are many kinds of adjacency pairs. Some

pairs involve similiar acts like greetings and goodbye, while others involve different

acts, like invitations or offers followed by acceptances or refusals, and question

followed by answer.

Below are two examples of common adjacency pairs in English taken from

Tracy (2002:114). These adjacency pairs involve different acts. Example (1) accepts an

invitation, and example (2) refuses an invitation.

Taryn : How about some lunch ? Invitation 1

Jjay : Sound good. (stand up) Acceptance

2 Taryn : How aout some lunch ?

Jay : (pause) Uhh, better bot.

I’ve got to get this done by 2:00.

Thanks though. How’s tomorrow ?

Invitation

There would be an expansion of adjacency pairs. This is done by presequence.

If a speaker wanted to invite someone for a dinner, it is reasonable for the speaker to

ask the invited person if he has eaten yet. An adjacency pairs usually a

question-answer format come first, as in Example (3) below :

Taryn : you eaten yet ? Question

Jay : No Answer

3

Taryn : How about some lunch ?. Invitation

Another expansion of adjecency pairs is done by insertion sequences. Like

presequences, insertion sequences involve an inserted adjecency pairs to determine if

some condition applies that would make the conversationally preferred option possible.

This is presented in example (4) below :

Taryn : How about some lunch ? Invitation

Jay : You got $ 5 to lend me ? Request

Taryn : Yeah. Grant

4

Jay : Sounds good. Acceptances

However, the notion of adjacency pair is not always the most usual sequence. It

is possible for a question not to be answered by an answer, greeting by a greeting.

When the answer is not forth coming it is noticeably absent (Schegloff in Tracy,

2002). In this case, it is possible for the speaker makes a repair. Schegloff (in Have,

1999) observed that from 500 instances of the telephone opening, one instance deviated

(police makes call)

Receiver is lifted, and there is one second pause

Police : Hello.

Other : American Red-cross

Police : Hello, this is police Headquartes, or Officer Stratton.

The common one is that a telephone ring is as a summons opens a conditional

relevance for second part of a sequence, answer. If the answer is not forthcoming a

summons can be reissued. In the above conversation, the police reissued a summons by

saying, hello.

Another respect of adjacency pairs is preferences. Conversational preferences

refers to structurally preferred second act for adjecency pairs that may take one of two

forms (Tracy, 2002).

In offer, invitation or request, accepts are conversationally preferred to refusals.

So, acceptances is a preferred action, and refusal in a dispreferred action. In English,

conversationally dispreferred act is always longer, more conversationnaly marked and

elaborated. In example (2) before, the refusal of Jay as dispreferred action was not

immediately given, but there was a pause before elaborating it.

It seem that conversational preference varies from culture to culture as what

different languages tell us about the different concept of space in a certain culture

2.4 Turn

A proposed unit of conversation seen as something said by the speaker preceded,

followed or both by a turn of some other speaker is called a turn (Mathews, 1997:417).

Whereas Goodwin (1981) stated that turn is the talk of one party bounded by the talk

of other. From these two defenition it can be implied that in turn, there is unit of

conversation and boundaries of talk or speaker change. Sacks, Schegloff, and Jefferson

(1974) stated that the unit of conversation refers to turn construction units (TCUs).

TCU is an utterance that is interpretable as recognizably complete. Grammar is

one key organizational resource in building and recognizing TCUs (Schegloff, 2007:3).

The second resource is phonetic realization, most familiarity in intonational packaging.

A speaker beginning to talk in a turn has the right and obligation to produce one TCU

which may realize one or more actions.

The conversation below is an example of which h TCUs are constructed as

giving actions, as quoted in Schiffrin (1994:6).

A : Can you pass the salt

B : Here you are

A : Thank you

B : You’re welcome

In this conversation, A makes 2 TCUs in two sentences : Can you past the salt ?, and

Thank you, A also performs two action : requesting and thanking. In similar case, B