Teacher nomination of ‘mathematically gifted

children with specific learning difficulties’

at three state schools in Jordan

Anies Al-Hroub and David Whitebread

In this article, Anies Al-Hroub, assistant professor of educational psychology and special educational needs at the American University of Beirut in Lebanon, and David Whitebread, senior lecturer in psychology and education in the University of Cambridge Faculty of Education, discuss the identi-fication, by teachers, of children who are gifted in mathematics and who also experience reading dif-ficulties or specific learning difdif-ficulties. The find-ings reported here are based on research carried out in three state schools in Jordan, and reveal the extent to which teachers accurately nominated the ‘dual-exceptional’ children studying in their classes. The paper reviews the issues and evidence relating to teacher nomination of these children and exam-ines the quality of teacher nominations by compar-ing them with identification procedures uscompar-ing psychological and dynamic testing. Anies Al-Hroub and David Whitebread reveal that the accuracy of the teacher nominations recorded in their research was highly variable and explore a series of factors influencing the processes of teacher nomination. They argue that teacher nomination is an essential first element in the identification process and can be easily improved. The authors call for professional development for teachers in order to raise aware-ness and to enable them to provide support for chil-dren with complex special educational needs more effectively.

Key words:gifted, mathematics, reading difficulties, teachers, identification.

Teacher nomination

Teacher nomination is one of the most widespread methods for identifying the mathematically gifted, but it is also one of the most troublesome (Davis & Rimm, 1998). This method is considered to be a basic element in the process of identi-fying ‘dual-exceptional’ pupils (Boodoo, Bradly, Frontera, Pitts & Wright, 1989). Teacher nomination of pupils to participate in the present research was the first part of the process of assessing mathematically gifted children with specific learning difficulties.

In McEachem and Bornot’s (2001) study, they report that it is classroom teachers who usually recognise pupils with

different learning needs from their peers, and approximately 80 to 85% of all referrals to special educational services and gifted programmes are made by mainstream classroom teachers.

However, in an interview (Vialle, 2002), Braggett has shown that teachers are likely to place major emphasis on actual achievement rather than aptitude, which may be masked by learning difficulty or underachievement. Teachers teach and then evaluate pupil achievement to see how well they have taught. When pupils do well on teachers’ tests, they are perceived to be high achievers, and in some cases, gifted. Teachers nominate pupils who have learnt best those things that the teachers themselves think it is important for them to learn.

As consequence of this and other issues, teacher nomination is probably the least effective method, if used alone, of identifying gifted children in the primary years, and the method most prone to cultural bias. The estimation of more than 400 secondary teachers in Germany and 400 in the USA were compared with 159 in Indonesia. The German teachers estimated that 3.5% of children were gifted, the Americans 6.4% and the Indonesians 17.4% (Dahme, 1996).

A multi-criteria identification procedure for primary school selection of the very able was devised in Jordan (Subhi, 1997). The research involved 25 schools with 4,583 Year 3 pupils (eight- to nine-year-olds), of whom 217 (4.74%) were identified in a wide trawl using standardised tests for intelligence, creativity, achievement, mathematical skills and task commitment (all translated into Arabic), as well as peer, self, teacher and parent nomination. No single proce-dure was found to be able to identify gifted pupils reliably. Teachers’ nominations were found to have missed 50 pupils with IQs above 130 (the cut-off point used in the study).

Betts and Neihart (1988) estimated that as many as 90% of children nominated as ‘gifted’ by untrained teachers are likely to be high-achieving conformists – teacher-pleasers ‘who often become bored in school but learn to use the system to get by with as little effort as possible’. Teacher nomination has also been shown to be prone to class bias. Children identified as gifted by teacher nomination alone are likely to come from middle-class families within the domi-nant culture (Ciha, Harris, Hiffman & Potter, 1974; Gross, 1993). There are other reasons for this low percentage of accurate nomination:

•

Teachers who have not been actively involved in gifted education might have inflated views about how exceptional a child has to be in order to qualify as being gifted (McBride, 1992).•

Inexperienced teachers of gifted children can be particularly unwilling to label children at such an early age.•

In McBride’s (1992) study, inexperienced teachers reported ‘not knowing what they were doing’ with respect to gifted education, and preferred to leave identification to psychologists.•

Teachers tend to stereotype giftedness, focusing only on academic or intellectual giftedness.•

When teacher nomination leads to referral to a segregated gifted programme, teachers tend to ‘play safe’ and avoid disappointment by nominating only those who are certain to be admitted (Hunsaker, Finley & Frank, 1997).However, as Gagne (1994) has indicated, teachers’ accu-racy in nominating gifted children can be improved easily. It has been found that the accuracy of teachers’ identifi-cation can double without raising the rate of false positives when they are trained to recognise advanced development and refer to a list of signs of advanced development. This can also be achieved when pupils are given challenging activities so that their talents can be revealed, and teachers have time to observe these talents. Extensive in-service training in gifted education can significantly increase teacher effectiveness (Gear, 1978), and teacher nomination forms and trait lists can be of some assistance in helping teachers to structure their observations of children in their classes, and in alerting the teachers to some of the behav-ioural characteristics of the gifted.

However, many of the trait lists published both in gifted education texts and as commercial materials focus on the behavioural traits and characteristics of moderately gifted pupils. A further problem is that these lists, with very few exceptions, concentrate on the positive characteristics of the gifted achiever, and ignore the negative or dysfunctional behaviours often displayed by gifted children whose schools have failed to make appropriate provision for them.

Gifted with specific learning difficulties

Controversy surrounds the concept of ‘dual-exceptional’ (Silverman, 1983), ‘doubly at risk’ (Robinson, 1999), ‘double-exceptional’ (Montgomery, 2003) or

‘twice-exceptional’ children (Baum, 2004), and what these terms mean. However, gifted pupils with specific learning difficul-ties are most commonly referred to as ‘dual-exceptional’ children (Erten, 2005; Silverman, 1989; Willard-Holt, 1999) and we have adopted this term in the present study. There are several subcategories of ‘dual-exceptionalities’, such as ‘gifted with specific learning difficulties’, ‘gifted with Asperger’s/autism’, ‘gifted with attention deficit disorder’, ‘gifted with dyslexia’, ‘gifted with dysgraphia’, ‘gifted with sensory disabilities’ and ‘gifted with behavioural disorders’ (Montgomery, 2003). In related literature, however, the term ‘dual-exceptionality’ is more commonly used to refer to the larger section of ‘gifted children with specific learning dif-ficulties’ (Silverman, 1983). In the current research, there-fore, gifted pupils who have high potential in mathematics, yet have specific learning difficulties related to literacy, are referred to as ‘dual-exceptional’ children.

Despite the extensive literature concerning individuals with extremely high abilities who also have specific learning dif-ficulties, there is a considerable lack of agreed definitions (Aaron, Phillips & Larsen, 1988; Brody & Mills, 1997; Hornsby, 1994; Montgomery, 2000). As Vaughn (1989) points out:

‘The definition of gifted children with [specific] learning difficulties is laden with controversy, as no two populations have suffered from more definitional problems than [specific] learning difficulties and gifted.’

(p. 123)

One of the difficulties that Vaughn (1989) and many educa-tors have found is the problem of distinguishing pupils with specific learning difficulties from other populations, such as pupils with language difficulties, bilingual pupils, socially and/or economically disadvantaged pupils, culturally differ-ent pupils and pupils with other cognitive deficits.

pupil and qualify for special services. In the USA, Brody and Mills (1997) pointed out that:

‘[None] of the [US] federal definitions of the gifted child excludes students with [specific] learning disabilities (difficulties) because the definitions (a) specify that a child does not need to be exceptional at each area to be gifted, (b) set no lower limits of performance or ability in remaining areas, and (c) specifically acknowledge that students can be gifted even if they are not currently performing at a high level, as long as they have the potential.’

(p. 3)

On the other hand, many definitions of specific learning difficulties have made reference to a discrepancy between pupils’ intellectual abilities and their academic achievement. The British Dyslexia Association (Crisfield, 1996) and the Warnock Report (DES, 1978) definitions of specific learning difficulties include, as well as some other definitions, a reference to discrepancies between pupils’ intellectual abi-lities and their academic achievement. However, when the Warnock Report (DES, 1978) defined a dyslexic as someone ‘whose abilities are at least average’ (Reid, 1994), and the Dyslexia Institute (1996, cited in Turner, 1997) stated that ‘Dyslexia can occur at any level of intellectual ability’, and when the Association for Children with Learning Disabilities (1985) proposed a definition for pupils with specific learning difficulties that specifically required ‘average and superior intelligence’ to accompany the difficulty, the door was opened wider for the possibility of recognising and identify-ing gifted children who have specific learnidentify-ing difficulties.

Baum and Owen (2004) defined gifted pupils with specific learning difficulties as having outstanding talents in some areas and debilitating weaknesses in others. Seven years earlier, Brody and Mills (1997) proposed the most useful definition of gifted pupils with specific learning difficulties to date. This definition includes a statement about their supe-rior ability, as well as their performance deficits, as follows:

‘Gifted/specific learning difficulties students are students of superior intellectual ability who exhibit a significant discrepancy in their level of performance in a particular academic area such as reading, mathematics, spelling or written expression. Their academic performance is substantially below what would be expected based on their general intellectual ability. As with other children exhibiting learning disabilities [difficulties], this discrepancy is not due to lack of educational opportunity in that academic area or other health impairment. Because academically gifted students with learning disabilities [specific learning difficulties] demonstrate such high academic potential, their academic achievement may not be as low as that of students with [specific] learning disabilities who demonstrate average academic potential. Consequently, these students may be less likely to be referred for special education testing.’

(p. 285)

Vaughn (1989) argued that the merger of two definitions of giftedness and specific learning difficulties multiplies the definition problems of each field. Therefore, schools from different countries have responded to the definitional diffi-culty by developing their own definitions. While ultimately this may be the best solution, a further inspection of broad and operational definitions in the literature can make the identification procedure more reliable.

Classification

At the present time, however, despite this increasing recog-nition of dual-exceptionality in the literature, it is clear that many dual-exceptional children remain unrecognised (Brody & Mills, 1997). According to Baum (1990), Brody and Mills (1997) and Sternberg and Grigorenko (2004), these dual-exceptional children who remain unrecognised can be classified into at least three subgroups, as follows.

1.Pupils with hidden specific learning difficulties

This first subgroup includes pupils who are identified as gifted, but also have difficulties in school; for example, those pupils who are often perceived as lazy, unmotivated, stub-born, careless and underachieving (Brody & Mills, 1997; Silverman, 1989; Waldron, Saphire & Rosenblum, 1987; Whitmore, 1980). Baum (1990) described these as ‘gifted pupils who have subtle [special] learning difficulties’. This group is easily identified as gifted; however, the gap between what is expected and their actual performance often tends to widen (Fetzer, 2000). This leaves many teachers confused, as they expect all children whom they have identified as gifted to achieve at a high level (Bisland, 2004). Accordingly, these pupils are considered to be underachievers, as many of them are working at grade level (Brody & Mills, 1997) or above (Little, 2001). This subgroup is likely to be recognised by the screening procedures that are necessary to identify undetected or subtle specific learning difficulties. Their underachievement may be attributed to poor self-esteem, lack of motivation, emotional and social problems, or lazi-ness (Brody & Mills, 1997), and they are often disorganised and ‘sloppy’ (Fetzer, 2000). They ‘may impress teachers with their verbal abilities, while their spelling or handwrit-ing contradicts the image’ (Baum, 1990).

Their specific learning difficulties usually remain unrecog-nised, until schoolwork becomes so challenging for them that their academic difficulties increase, to the point where their progress falls considerably behind that of their peers (Baum, 1994; Baum, Emerick, Herman & Dixon, 1989; Beckley, 1998; Brody & Mills; 1997; Gunderson, Maesch & Rees, 1987). Only then does a teacher or a parent eventually consider the possibility that they might have specific learn-ing difficulties (Beckley, 1998).

2.Pupils with hidden giftedness

2001). It has been suggested that this may be a larger group of pupils than many teachers and parents realise. Baum (1985) found that as many as 33% of pupils with specific learning difficulties had superior intellectual abilities. Inad-equate assessment and/or depressed IQ scores usually lead to an underestimation of pupils’ intellectual abilities (Brody & Mills, 1997). This group of pupils is most at risk, because the specific learning difficulties categorisation implies the existence of a difficulty which must be addressed before anything else can happen. As a consequence, they are infre-quently referred for ‘gifted services’. Research has shown that this group of pupils is usually rated by teachers as the most unruly at school. They are frequently found to be off-task and easily frustrated, and they often use their cre-ative skills to avoid tasks (Baum & Owen, 1988; Whitmore, 1980).

3.Pupils with hidden giftedness and specific

learning difficulties

This third subgroup, and ‘perhaps the largest group of non-served and unidentified pupils’ (Brody & Mills, 1997), are those whose high abilities and specific learning difficulties mask each other (Baum, 1990; Brody & Mills, 1997; Fetzer, 2000). These pupils sit in mainstream classrooms, and are considered unqualified for services provided for pupils who are gifted or have specific learning difficulties, and are thought to have average abilities (Brody & Mills, 1997). Typically, these pupils function at the level that would be expected for children at their chronological age (Bisland, 2004), and perform poorly on group-administered intelli-gence tests as a result of the interference of specific learning difficulties (Brody & Mills, 1997).

Correspondingly, while they may perform well in classroom discussions, they may not perform well on tests that deter-mine specific academic achievement. As coursework becomes more challenging in later years, their academic difficulties usually increase to the point where a specific learning difficulty may be suspected; this is frequently dis-covered at university or adulthood when they happen to read or hear peers describe their specific learning difficulties, but rarely is their exceptional potential recognised (Baum, 1994; Baum et al., 1989; Beckley, 1998; Brody & Mills, 1997; Gunderson et al., 1987; Porter, 1999).

Prevalence

In the literature, only a small percentage of gifted pupils with specific learning difficulties (for example, difficulty in reading and writing) have been previously recognised, partly because of the difficulties of identification discussed above. For example, according to a Department of Education Office for Civil Rights survey (Department of Education Office, 1992), there were 24,241 people in the US who were iden-tified as being both ‘learning disabled’ and gifted. This number was almost certainly a considerable underestimate.

The widespread Talent Searches in the UK normally select a broader band of pupils for gifted programmes. This broad-ness sits comfortably with British notions of giftedbroad-ness, where a broad concept embracing around the top 20% to

25% of the population seems to be more natural (DfES, 2001). This is the proportion recommended in the UK Department of Education and Employment Select Commit-tee Report (DfEE, 1999), and is the proportion most fre-quently used for grammar school selection. At the same time, the National Association for Gifted Education (2001) reported that a recent estimate suggests that 5% to 10% of gifted children could have specific learning difficulties. This suggests that, according to the British notions of giftedness, the percentage of ‘dual-exceptional’ children in schools would be between 1% and 2.5%.

However, although researchers have acknowledged the ‘dual-exceptional’ population, information on this popula-tion has not been transferred into the classroom, so teachers are often not aware of the possibility of ‘dual-exceptionalities’ in these areas. These obstacles have made it difficult for the ‘dual-exceptional’ child to be identified, although this population is more widely found than perhaps had been expected (Montgomery, 2003). There is very little consensus in the literature regarding the percentage of ‘dual-exceptional’ pupils. Silverman (1989), for example, found that one-third of the gifted in her large sample had learning difficulties. While some estimations of the incidence of ‘dual-exceptional’ pupils range from 2% to 5% of the general gifted pupil population (Whitmore, 1980, cited in Macfarlane, 2000), Dix and Schafer (1996) pointed out that the conservative estimate is that between 5% and 10% of all children enrolled in gifted programmes have specific learn-ing difficulties. Furthermore, the pupils who maintain average achievement often go unrecognised, and discover later in life, usually while at university, that they have a specific learning difficulty (Baum, 1990). Approximately 41% of gifted pupils with specific learning difficulties are not diagnosed until they go to university (Ferri, Gregg & Heggoy, 1997).

One reason for the variation of these statistics related to the prevalence of gifted children with specific learning difficul-ties is that different studies inevitably use different criteria for assessment. For this reason, and because of the multiple difficulties of identification discussed above, it is very dif-ficult to be certain of the accuracy of these various estimates.

Teacher seminars

This section discusses instructional seminars which were designed to extend teachers’ concepts of mathematically gifted children with specific learning difficulties; that is, ‘dual-exceptional’ pupils. It also examines teachers’ responses towards this new notion, which is beyond their general exploratory experiences.

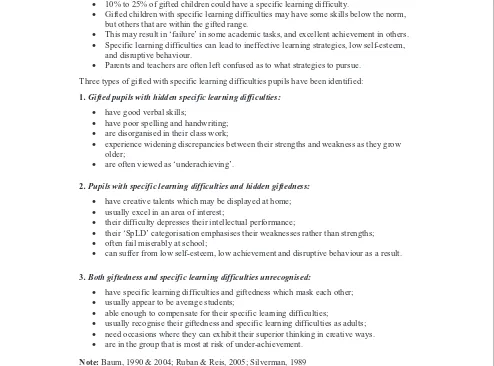

The purpose of the seminars was to discuss the concept of ‘dual-exceptional’ children and their characteristics, in order to draw a clear picture of this population of pupils. Teachers were also instructed about the three subgroups of children whose dual-exceptionality remains unrecognised (Baum, 1994; Baum & Owen, 2004; Baum, Owen & Dixon, 1991; Fetzer, 2000; Fox, Brody & Tobin, 1983; Landrum, 1989; Ruban & Reis, 2005), in order to help the teachers to make more accurate nominations. More specifically, a trait list of the characteristics, strengths and weaknesses of the three subgroups of ‘gifted children with specific learning difficul-ties’ was given to all teachers, in order to assist them to structure their observations of the children, and, conse-quently, to recognise them in their classrooms (see Figure 1). The seminars included discussion of the broad definitions of giftedness and specific learning difficulties, and the characteristics and three categories that classified ‘dual-exceptional’ pupils in the literature. Questions were asked, and specific explanations were given to all of the teachers concerning the definition of the various terms, and why ‘dual-exceptional’ pupils are difficult to recognise. The seminars also involved discussion of the fact that teacher judgements may not necessarily correspond very well to pupils’ scores on achievement and schools tests. At the same time, the teachers retained some freedom in their definitions

of which pupils to include. They were expected to include not only high achievers, but also pupils with potential for high achievement that had not yet been realised.

Although most of the teachers were unfamiliar with the concept of ‘dual-exceptionality’, most of them recognised its existence. Some teachers explained the difficulties of recognising such pupils at school. One crucial barrier that was mentioned was the large number of pupils in class-rooms, which made it difficult for the class teacher to iden-tify individual needs. Two teachers, one male and one female, expressed their astonishment at the possibility of the co-existence of giftedness and specific learning diffi-culties, but later they narrated some stories about different cases of pupils they had taught, which appeared to support this new notion. One male teacher showed his disagree-ment with the notion of dual-exceptionality and did not nominate any children from his classes. However, the researcher was advised by the headteacher that this teacher was performing very poorly and was shortly to be replaced at the school, so this situation may have affected his atti-tude to the seminars and the research study. After the semi-nars, many teachers asked several times for further information concerning ‘dual-exceptionality’ and how to recognise such dual-exceptional pupils.

Figure 1: List of traits and characteristics of gifted children with specific learning difficulties

• 10% to 25% of gifted children could have a specific learning difficulty.

• Gifted children with specific learning difficulties may have some skills below the norm,

but others that are within the gifted range.

• This may result in ‘failure’ in some academic tasks, and excellent achievement in others.

• Specific learning difficulties can lead to ineffective learning strategies, low self-esteem,

and disruptive behaviour.

• Parents and teachers are often left confused as to what strategies to pursue.

Three types of gifted with specific learning difficulties pupils have been identified:

1. Gifted pupils with hidden specific learning difficulties:

• have good verbal skills;

• have poor spelling and handwriting;

• are disorganised in their class work;

• experience widening discrepancies between their strengths and weakness as they grow

older;

• are often viewed as ‘underachieving’.

2. Pupils with specific learning difficulties and hidden giftedness:

• have creative talents which may be displayed at home;

• usually excel in an area of interest;

• their difficulty depresses their intellectual performance;

• their ‘SpLD’ categorisation emphasises their weaknesses rather than strengths;

• often fail miserably at school;

• can suffer from low self-esteem, low achievement and disruptive behaviour as a result.

3. Both giftedness and specific learning difficulties unrecognised:

• have specific learning difficulties and giftedness which mask each other;

• usually appear to be average students;

• able enough to compensate for their specific learning difficulties;

• usually recognise their giftedness and specific learning difficulties as adults;

• need occasions where they can exhibit their superior thinking in creative ways.

• are in the group that is most at risk of under-achievement.

Subsequently, the Arabic and mathematics teachers were interviewed individually, and were asked to complete a nomination form which asked them to describe the nomi-nated pupils under six headings. These focused on pupils’ strengths and weaknesses in mathematics, language and lit-eracy; namely, reading, speaking, writing and spelling, and high potentiality in solving problems, all of which are important criteria for the identification of any aspects of mathematical giftedness or specific learning difficulties.

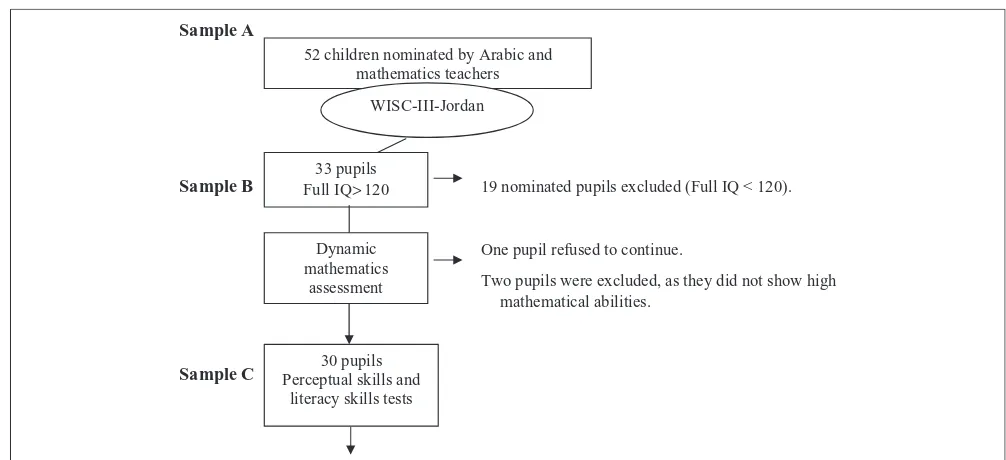

The teachers nominated 52 pupils (sample A; see Figure 2), who received parental permission and were willing to con-tinue with the study. Of these pupils, 26 were boys, and 26 were girls. Thirty pupils (14 boys and 16 girls) were sub-sequently identified through psychological and dynamic assessment as fitting the concept of ‘dual-exceptionality’. Following the process of teachers’ nomination, the researcher administered the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children (third Jordanian version) (WISC-III-Jordan) with all of the nominated 52 pupils. Nineteen pupils (11 boys and eight girls) were excluded from the study, because their Full IQs were revealed to be below the cut-off point of 120, the score that is considered to be the baseline for ‘above-average pupils’ (Wechsler, 1991). A further two girls who scored above 120 were excluded, as they showed specific learning difficulties, but did not show special mathematical abilities when the researcher assessed their mathematical abilities and potential by means of dynamic assessment. One girl refused to proceed in this investigation, contrary to her parents’ wishes, although her IQ scores showed that she was in the ‘superior’ range. So, altogether, 22 of the 52 nomi-nated pupils were excluded from the sample, leaving 30 pupils who were identified as ‘dual-exceptional’ pupils, being mathematically gifted but also having specific learn-ing difficulties.

Results and conclusions

This section is arranged into four subsections: population versus nominated cases; population versus sample; sample versus nominated cases (results); and factors influencing teacher nomination (conclusions). The first three subsec-tions examine the relative proporsubsec-tions of the population of dual-exceptional children, the cases nominated by the teach-ers, and the final sample. The need to examine these propor-tions arises from the scarcity of studies specifically relating to the proportions of children who are gifted and/or have specific learning difficulties (Al-Hroub, 2005). The fourth subsection discusses the factors that support or impede accurate teacher nomination.

1.Population versus nominated cases (sample A)

As mentioned earlier, mainstream classroom teachers (of Arabic and mathematics) nominated the pupils from three state-maintained (government-funded) schools. Schools were selected for the following reasons: (1) the large number of pupils at these schools; (2) these schools are government-funded, as are the majority of schools in Jordan; and (3) these schools had students of middle-class socio-economic background in the capital Amman. The use of these criteria was intended, at least in part, to neutralise as many con-founding factors as possible. For example, schools with upper-class students were avoided, as they have a different set of problems pertaining to learning difficulties. These schools are normally bilingual or sometimes trilingual, which creates language problems for many of the children, rather than learning problems, that affect their first (Arabic) language abilities negatively. The same applies to those schools in economically and socially disadvantaged areas, although in a different way. Students at those schools may suffer more frequently from social and emotional problems that could be confused with learning difficulties in a fashion that is unhelpful for the present research.

Figure 2: Development of core sample in the research identification phase

Sample A

Sample B 19 nominated pupils excluded (Full IQ < 120).

One pupil refused to continue.

Two pupils were excluded, as they did not show high mathematical abilities.

Sample C

52 children nominated by Arabic and mathematics teachers

WISC-III-Jordan

33 pupils

Full IQ> 120

Dynamic mathematics

assessment

30 pupils Perceptual skills and

literacy skills tests

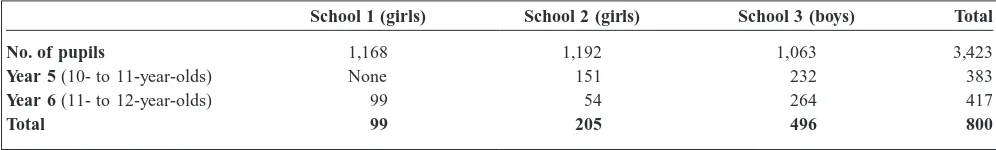

Table 1 sets out the numbers of pupils in these schools overall, and the numbers in Years 5 and 6. The total number of the pupils in the three schools was 3,423 pupils. The number of pupils in each school was as follows: 1,168; 1,192; and 1,063 pupils respectively.

However, pupils were nominated from a total population of 800 pupils across Years 5 and 6 in the three selected schools. More specifically, their numbers in these Years were 99,205 and 496 respectively in the three schools. According to these figures, the 52 pupils nominated as ‘dual-exceptional’ rep-resented 6.5% of pupils across the three schools involved in the research.

Table 2 reports the number of boys and girls nominated and identified as ‘dual-exceptional’. Taking an average across all participating schools, 5.2% of boys were nominated as ‘dual-exceptional’ pupils, and 8.6% of girls; a divergence of 3.4% in favour of girls. These findings disagree with the general statistics that indicate that more boys than girls are identified as ‘gifted with specific learning difficulties’ (Stewart, 2003). These statistics resulted from the fact that more boys than girls (a ratio of 4:1) are found to have specific learning difficulties, although this has been chal-lenged by Shaywitz (1995), who suggested that the ratios are equal.

However, the mean percentage masks a more complex reality. Teachers were asked, in this investigation, to nomi-nate not only pupils who are mathematically gifted, but also who show specific learning difficulties. Accordingly, this nominated proportion is high or low depending on whether these mainstream classroom teachers adopted a narrow or broad definition of ‘dual-exceptional’ pupils.

In practice, teachers in Jordan appear to prefer Silverman’s proportion, using it commonly in banding or setting by ability, and in primary schools, when two or three out of a class of 30 are chosen to sit together as a ‘dual-exceptional’ group. In other words, this means that the expected

propor-tion of pupils to be nominated as gifted (in all areas) with specific learning difficulties should be between 7% and 10%, whereas teachers in the current research nominated 6.5% of the population as gifted (in mathematics) with spe-cific learning difficulties.

This result appears to be a large proportion, especially when it is considered that teachers were asked to nominate pupils who are gifted in mathematics. This does not mean, of course, that the researcher asked the teachers not to nomi-nate pupils who had other talents. Some pupils showed high abilities and talents in other specific areas, such as drawing and art, but these talents were not considered, since they did not relate to the research aim. Furthermore, the fact that two types of teacher (mathematics and Arabic) had to co-operate to determine the nominated pupils made the process of pupil nomination more difficult. Mathematics teachers did not have a complete picture about their pupils’ weaknesses in literacy and had to ask their Arabic teachers. Conversely, Arabic teachers did not claim that they identified all of the pupils who suffered from specific learning difficulties. At the same time, they were not aware if the identified pupils had high mathematical abilities; consequently, they had to meet with the mathematics teachers to discuss every case.

2.Population versus sample (C)

By comparing the number of pupils in the final sample (sample C=30 pupils; see Figure 2) – that is, those pupils nominated who were also identified as being mathematically gifted with specific learning difficulties by psychological and dynamic assessment – with the population of the study, we could conclude that the sample represents 3.8% of pupils in Years 5 and 6 across all of the selected schools in this study.

One probable explanation for the estimated percentage varying between different studies is that the process used to estimate is heavily dependent on the methods used to access pupils, in addition to where they live. Most countries use standardised tests of some kind, usually as one step in the Table 1: Number of male and female pupils in Years 5 and 6 at the three schools

School 1 (girls) School 2 (girls) School 3 (boys) Total

No. of pupils 1,168 1,192 1,063 3,423

Year 5(10- to 11-year-olds) None 151 232 383

Year 6(11- to 12-year-olds) 99 54 264 417

Total 99 205 496 800

Table 2: Numbers of nominated and identified boys and girls from Years 5 and 6

Number of boys

Nominated boys

Identified as MG/SpLD

Number of girls

Nominated girls

Identified as MG/SpLD

Year 5 232 16 7 151 9 7

Year 6 264 10 7 153 17 9

identification procedure, but differences in sample size and application make it difficult to compare the outcome reliably, as found in this study. Attempting to define a per-centage is further complicated because the top x% in one population almost always differ from the topx% in another population. In this research, multidisciplinary assessments were used, and this assessment enlarged the sample size to 3.8% of the general population across all Year 5 and 6 (ten-to 12-year-olds) classes. Additionally, the selected schools were located, as stated earlier, in middle-class socio-economic areas in the capital of Jordan, Amman, which may also have contributed to the emergence of a larger sample than expected. In previous findings, Ciha et al. (1974) and Gross (1993) indicated that children identified by teacher nomination alone are likely to come from middle-class fami-lies within the dominant culture.

3.Sample (C) versus nominated cases (sample A)

By comparing the number of pupils who were nominated (sample A=52 pupils) with the number of pupils who were identified through psychological and dynamic assessment (sample C=30 pupils), it appears that 57.6% of teachers’ nominations were accurate, whereas 42.4% were incorrect. Therefore this study found a wide variation between teacher judgements and objective measures.

Individually, teachers’ attitudes towards very able pupils with specific learning difficulties varied greatly; some felt resent-ment, while others overestimated their all-round abilities, as was found in a Finnish–British survey (Ojanen & Freeman, 1994) on the subject of gifted pupils. As a consequence, perhaps not surprisingly, the evidence from previous studies on the accuracy of teacher nominations has been inconsistent.

In some previous studies, teachers have been found to judge the highly able consistently, in that they will continue to pick the same kind of children (Hany, 1993). In contrast, the present study found that 42.4% of nominated pupils had been overestimated by their teachers. This finding agrees with Nebesnuik’s (cited in Eyre, 1997) study, which showed ‘a significant discrepancy between the assessment of able pupils by their primary teachers and subsequently by Year 7 teachers [pupils aged 11 and 12]’: the primary teachers often judged children as being able on the basis of their ways of working, rather than their cognitive ability.

In the present study, IQ and dynamic mathematics assess-ment were used as two criteria for the identification of ‘mathematical giftedness’. As for the IQ criterion of gifted-ness, it was found that of the 52 pupils identified by their teachers as mathematically ‘gifted with specific learning difficulties’, only 33 had IQs above 120 and 19 had IQs under 120 (one girl refused, contrary to her parents wishes, to continue to participate in this study, although her Full IQ scores set her in the superior range). While only three high average pupils scored between 110 and 119, a total of 16 average pupils scored between 90 and 109. However, two girls who scored above 120 on the IQ scale did not subse-quently show high mathematical abilities, according to the dynamic assessment procedure. This suggests that teacher

nomination alone was not reliable. Similarly, Tempest (1974) in Southport, UK, found that out of 72 six-year-olds identified by their teachers as gifted, only 24 had IQs of 127 or above and seven had IQs of under 110, but two children with reading ages that were six years ahead of their chrono-logical age were not nominated as gifted.

4.Factors influencing teacher nomination

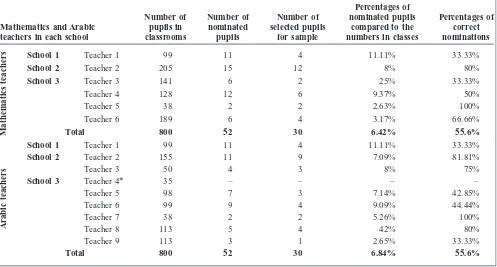

Naturally, teachers’ judgements of their pupils’ abilities affect their expectations and treatment of them. We do not investigate in this study how any teacher’s personal concep-tions or stereotypes of giftedness and/or specific learning difficulties affected his/her teaching or nominations. It is interesting to record, however, that teachers who showed very high levels of interest in understanding and exploring the notion of ‘dual-exceptionality’ during teacher seminars (such as mathematics teachers 2 and 5, and Arabic language teachers 2 and 8 in Table 3) were among the most accurate in their nominations of this group of pupils.

Hany (1997) investigated how 58 secondary school teachers in Germany judged giftedness, using a rating scale of 60 suggested traits. The teachers seemed to be biased in certain aspects of their judgements, as will be discussed below. Theoretically, teachers’ competence in recognising ‘dual-exceptionality’ is likely to be far from optimal. Three con-tributing factors can be identified, as follows:

1. The concept of ‘mathematically gifted children with specific learning difficulties’ is not easily accepted and understood by class teachers. This is not surprising, because the ‘experts’ in each of these disciplines have difficulty in reaching agreement about this concept. Some teachers still believe that giftedness is equated with outstanding achievement across all subject areas (Baum, 1990).

2. Teachers often find it difficult to accept the idea that children who perform very poorly could possess unrea-lised intellectual potential (Hanses & Rost, 1998, cited in Hany, 1998). Hany (1998) added that the teachers’ understanding of giftedness does not allow for the inclusion of underachievers or poorly performing chil-dren in this category. According to Schiff, Kaufman and Kaufman (1981), the failure of teachers to refer these children very frequently, particularly early in their school careers, is not surprising in view of the children’s level of academic achievement.

3. Few empirical studies on the quality of teacher judgement are heterogeneous. Some of them completely reject teachers’ data as invalid and unreliable. Other studies value teachers’ judgement highly (Hoge & Cudmore, 1986). It is clear, however, that the quality of teachers’ judgements varies a great deal, but the factors related to this remain unexplored.

1. There were considerable individual differences between teachers, as can be seen in Table 3. Teachers differed substantially in their estimates of how many pupils had ‘dual-exceptionality’. Some teachers nominated between five and seven pupils from one class, and others overlooked whole classes.

Individually, teachers’ attitudes towards the very able varied greatly; some felt resentment, while others overestimated their all-round abilities.

Furthermore, the teachers differed significantly in the accuracy of their nominations. For example, the nomi-nations of six teachers were more than 80% correct, whereas seven teachers’ nominations were less than 50% correct. In school 3, nominations varied between 33.33% and 100%. Table 4 shows that the percentages of accurate nominations at schools 1, 2 and 3 were as follows: 33.3%, 80% and 53.8% respectively.

2. Generally, most teachers stated after the assessment phase that they had picked out children because of their school achievement. This confirms Hany’s (1993) report that teachers have been found to judge

highly able pupils consistently, in that they will continue to pick the same high achievers. However, this criterion led teachers to overestimate the ability of most of the 20 excluded pupils in this research. These results also indicate that the teachers were still using the traditional way of recognising gifted children with specific learning difficulties.

3. Obviously, many of the teachers involved in this study found it difficult to recognise ‘dual-exceptional’ pupils in large classes. The average size of classes in the three groups was 40 pupils. Thus, many teachers found it easier to focus on pupils’ behaviour rather than their abilities.

4. Different teachers made their judgements according to specific pupils’ characteristics, such as: his/her contri-bution in the classroom, his/her hyperactivity, and the strength of his/her personality. Also, teachers’ nomina-tions were correlated with positive social characteris-tics of the child (such as independence, responsibility and social sensibility). This finding suggests that many teachers chose pupils who lived up to their expecta-tions most, rather than focusing on the characteristics Table 4: Percentage of the identified mathematically gifted pupils with specific learning difficulties compared to the nominated pupils in the three selected schools

School 1 (girls) School 2 (girls) School 3 (boys) Total number and percentage

Nominated pupils 11 15 26 52

Identified as MG/SpLD 4 12 14 30

Percentages of identified MG/SpLD 33.3% 80% 53.8% 55.6%

Note:MG/SpLD; mathematically gifted with specific learning difficulties.

Table 3: Individual differences in teachers’ nominations

Mathematics and Arabic teachers in each school

Number of pupils in classrooms

Number of nominated

pupils

Number of selected pupils

for sample

Percentages of nominated pupils

compared to the numbers in classes

Percentages of correct nominations

Mathematics

teacher

s School 1 Teacher 1 99 11 4 11.11% 33.33%

School 2 Teacher 2 205 15 12 8% 80%

School 3 Teacher 3 141 6 2 25% 33.33%

Teacher 4 128 12 6 9.37% 50%

Teacher 5 38 2 2 2.63% 100%

Teacher 6 189 6 4 3.17% 66.66%

Total 800 52 30 6.42% 55.6%

Ar

a

bic

teacher

s

School 1 Teacher 1 99 11 4 11.11% 33.33%

School 2 Teacher 2 155 11 9 7.09% 81.81%

Teacher 3 50 4 3 8% 75%

School 3 Teacher 4* 35 – – – –

Teacher 5 98 7 3 7.14% 42.85%

Teacher 6 99 9 4 9.09% 44.44%

Teacher 7 38 2 2 5.26% 100%

Teacher 8 113 5 4 42% 80%

Teacher 9 113 3 1 2.65% 33.33%

Total 800 52 30 6.84% 55.6%

of ‘dual-exceptional’ children which were discussed in the seminars. In an investigation by Chyriwsky and Kennard (1997) into mathematics teachers’ attitudes towards able pupils in 500 English comprehensive schools, the researchers presented the teachers with suggested lists of the characteristics of mathematically able children. The teachers generally agreed with these, but also expressed concern that such pupils were both educationally under-challenged and frequently deterred by peer-group pressure. The teachers often felt hindered by constraints on time and material resources in teaching very able children, and the fact that any available extra provision was targeted towards the least able children.

5. Of those pupils nominated as ‘dual-exceptional’, 37% were found to have IQs below the cut-off point of 120. However, it had been explained in the instructional seminars that perhaps the largest subgroup of ‘dual-exceptional’ pupils consists of those whose specific learning difficulties are so severe that they are identi-fied as having specific learning difficulties, but whose exceptional abilities have never been recognised or addressed (Baum, 1994). In one study, as many as 33% of pupils who had been identified with specific learn-ing difficulties had superior intellectual ability. In this study, most of the teachers overestimated the pupils, as 19 nominated pupils did not show high intellectual abilities on the WISC-III-Jordan test. However, in the instructional seminar, teachers were told that, due to underestimation and/or instructional expectations of ‘dual-exceptional’ pupils, they are rarely referred to gifted programmes. This may have encouraged the teachers to overestimate some pupils with obvious spe-cific learning difficulties.

6. The nomination procedures were complicated, since there were different mathematics and Arabic teachers for the Year 5 and 6 (ten- to 12-year-olds) classes. Gen-erally, Arabic teachers were also the form class teach-ers in the three selected schools. Accordingly, all of the teachers agreed that Arabic teachers, in par-ticular, should take the lead for the nomination of the ‘dual-exceptional’ pupils. As a consequence, the normal procedure adopted was that the Arabic teachers selected a group of pupils who had specific learning difficulties in reading and writing, and transferred the list of the names to the mathematics teachers. The mathematics teachers then screened the list by choos-ing the pupils who, in their opinion, had high abilities in mathematics. Obviously, it was assumed that the identification of specific learning difficulties was the first step in the process, although it contradicts the normal procedure in this area, whereby the identifica-tion of mathematical giftedness is the first step in iden-tifying ‘dual-exceptional’ pupils. Accordingly, teachers in general concentrated more on the negative aspects of the pupil profiles, rather than the positive ones. As a result, most of the nominated pupils were found to have specific learning difficulties with/without high abilities of mathematics. This also explains why no pupils were identified as mathematically gifted but

with no specific learning difficulties. Powell and Siegle (2000) and Siegle and Powell (2004) discussed the fact that classroom teachers are often cast in the role of diagnosing and remediating with pupils. As a result of this, they may be more sensitive to pupils’ weaknesses. When they are asked to identify gifted pupils, they need to be encouraged to identify characteristics that indicate giftedness, rather than looking for reasons as to why a particular pupil is not gifted.

Summary

The analysis of the teachers’ nominations showed that 57.6% of them were accurate, whereas 42.4% were not accurate. Arabic language and mathematics teachers showed a broad inter-individual variance in the accuracy of their nomina-tions. Consequently, the accuracy of the three primary schools’ nominations varied between 33.3% and 80%.

According to several researchers (for example, Rizza & Morrison, 2003; Whitmore & Maker, 1985), teachers do not receive adequate training in the field of special education to make them aware that the characteristics of one exception-ality may co-exist with those of other exceptionalities (that is, giftedness and specific learning difficulties). Therefore, it appears likely that extensive pre- and in-service training in gifted/special education could significantly increase the accuracy of teacher nominations. At the same time, models of teacher–parent communication and collaboration in iden-tifying ‘gifted pupils with specific learning difficulties’ could be investigated. For example, parents’ judgements of their children could assist teachers in observing their behav-ioural and cognitive characteristics.

reference should not be applied, because the comparison with normal pupils may lead to a biased result.

Nevertheless, despite the low degree of accuracy of teacher nominations found in the present study and elsewhere, the findings support the idea that teacher nomination must con-tinue to be the first element of the identification process. The large number of pupils at schools makes it impossible to identify ‘dual-exceptional’ pupils without taking teachers’ judgements into consideration. Consequently, it is recom-mended that teacher nomination should be the first step in the whole identification process of ‘dual-exceptional’ pupils. It is hoped that one outcome of work in this field, of which the present research is part, may be to help teachers to improve their awareness and understanding of dual-exceptionality, and thus the accuracy of their nominations.

The present study involved teachers who had taught for at least ten years, and thus were all relatively experienced. Schwartz et al. (1997, cited in Rizza & Morrison, 2003) found that length of teaching experience had a significant influence on types of referrals to special education pro-grammes. For example, novice teachers tend to use their own perceptions rather than objective data to identify pupils with special needs. This finding is particularly relevant to the current study, because teachers were asked to use their own judgement and experience, in addition to the trait list of observable data. Therefore, additional checklists of the sup-posed characteristics of gifted children with specific learn-ing difficulties can be of some assistance in helplearn-ing novice

teachers to recognise pupils with ‘dual-exceptionalities’. They may stimulate novice and experienced teachers to think about the identification of this group of pupils. However, checklists vary considerably, and some of the items can be confusing or misleading. Some of the most reliable research-based criteria that distinguish this group of pupils from others could be reasonably used in a checklist, and are listed in Stewart’s (2003) review of the literature in this area, grouped under three main categories of character-istic: cognitive, meta-cognitive and affective.

At the international level, there has been a considerable increase in awareness in the last few years regarding the importance of accurate identification of gifted children, and there are many publications on this topic. The Department for Children, Schools and Families (DCSF) in the UK also has a plethora of useful advice and support materials for teachers and schools on their website [http://www. standards.dfes.gov.uk/giftedandtalented/]. There is also a recent DCSF publication on the subject of dual-exceptional children, entitled ‘Gifted and Talented Education: helping to find and support children with dual or multiple exception-alities’ [online at http://www.standards.dfes.gov.uk/primary/ publications/inclusion/gt_findsuportdme/].

This latter publication is very timely, and it is hoped that this and other resources (for example, Stewart, 2003), will help teachers to improve their abilities to identify and nominate children in this important but neglected category.

References

Aaron, P. G., Phillips, S. & Larsen, S. (1988) ‘Specific reading disability in historically famous persons’,

Journal of Learning Disabilities, 21, 523–538.

Al-Hroub, A. (2002) ‘Gifted children with learning difficulties: mathematics as a model.’ Unpublished MPhil thesis. Cambridge University.

Al-Hroub, A. (2005) ‘Teacher nomination of the “Mathematically Gifted Children with Learning Difficulties” at three state maintained schools in Jordan.’ Paper presented at the annual CamERA Conference, Faculty of Education, Cambridge University, 21 April 2005.

Association for Children with Learning Disabilities (1985) ‘Definition of the condition of specific learning disabilities’,ACLD Newsbriefs, 158, 1–3.

Baum, S. (1985) ‘Learning disabled students with superior cognitive abilities: a validity study of descriptive behaviours.’ Unpublished PhD thesis. Storrs, CN: University of Connecticut [online at http:// www.lib.umi.com/dissertations/fullcit/8516176]. Baum, S. (1990) ‘Gifted but learning disabled: a puzzling

paradox’ [online at http://www.ovid.bid.ac.uk/ovidweb/ ovidweb.cgi?T=selCit&F=ftwarn&A=display&S].

Baum, S. (1994) ‘Meeting the needs of gifted/learning disabled students’,Journal of Secondary Gifted

Education, 5 (3), 6–16.

Baum, S. (2004) ‘Twice-exceptional and special populations of gifted students’, in S. M. Reis (ed.),

Essential Readings in Gifted Education. Thousand

Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Baum, S., Emerick, L. J., Herman, G. N. & Dixon, J. (1989) ‘Identification programmes and enrichment strategies for gifted learning disabled youth’,Roeper

Review, 12 (1), 48–53.

Baum, S. & Owen, S. (1988) ‘High ability/learning disabled students: how are they different?’Gifted Child

Quarterly, 32, 226–230.

Baum, S. & Owen, S. (2004)To Be Gifted and Learning Disabled: strategies for helping bright students with

LD, ADHD, and more. Mansfield Center, CT: Creative

Learning Press.

Baum, S., Owen, S. V. & Dixon, J. (1991)To Be Gifted and Learning Disabled: from identification to practical

intervention strategies. Mansfield, CT: Creative

Learning Press.

Betts, G. T. & Neihart, M. (1988) ‘Profiles of the gifted and talented’,Gifted Child Quarterly, 32 (2), 248–253. Bisland, A. (2004) ‘Using learning-strategies instruction

with students who are gifted and learning disabled’,

Gifted Child Today Magazine[online at http://

www.findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m0HRV/is_3_27/ ai_n6142304].

Boodoo, G., Bradly, C., Frontera, R., Pitts, J. & Wright, L. (1989) ‘A survey of procedure used for identifying gifted learning disabled children’,Gifted Child

Quarterly, 33 (3), 110–114.

Brody, L. E. & Mills, C. J. (1997) ‘Gifted children with learning disabilities: a review of the issues’,Journal of

Learning Disabilities, 30, 282–297.

Chyriwsky, M. & Kennard, R. (1997) ‘Attitudes to able children; a survey of mathematics teachers in English secondary schools’,High Ability Studies, 8, 47–59. Ciha, T. E., Harris, T. E., Hiffman, C. & Potter, M. W.

(1974) ‘Parents as identifiers of giftedness, ignored but accurate’,Gifted Child Quarterly, 18, 191–195. Crisfield, J. (1996)The Dyslexia Handbook 1996.

Reading: British Dyslexia Association.

Dahme, G. (1996) ‘Teachers’ conceptions of gifted students in Indonesia (Java), Germany and USA.’ Paper given at the Fifth Conference of the European Council for High Ability, Vienna, September 1996.

Davis, G. & Rimm, S. (1998)Education of the Gifted and

Talented(fourth edition). Needham Heights, MA: Allyn

& Bacon.

Department of Education Office (1992) ‘Civil Rights Survey’,Annual Report to Congress. Washington, DC: Department of Education.

DES (Department of Education and Science) (1978)

Special Educational Needs. Report of the Committee of Enquiry into the Education of Handicapped

Children and Young People (Warnock Report). London:

HMSO.

DfEE (Department for Education and Employment Select Committee) (1999)Third Report: highly able children. London: HMSO.

DfES (Department for Education and Skills) (2001)

Schools: achieving success. London: Stationery Office

[online at http://www.joanfreeman.com/content/ Text%20part%20two.doc].

Dix, J. & Schafer, S. (1996) ‘From paradox to

performance: practical strategies for identifying and teaching gt/ld students’,Gifted Child Today Magazine, 19, 22–31.

Erten, O. (2005) ‘Giftedness and learning disabilities: a dual exceptionality’ [online at http://www.

searchwarp.com/swa23275.htm].

Eyre, D. (1997)Able Children in Ordinary Schools. London: David Fulton.

Ferri, B., Gregg, N. & Heggoy, S. (1997) ‘Profiles of college students demonstrating learning disabilities with and without giftedness’,Journal of Learning

Disabilities, 30, 552–559.

Fetzer, E. A. (2000) ‘The gifted/learning-disabled child: a guide for teachers and parents’,Gifted Child Today, 23 (4), 44–50.

Fox, L., Brody, L. & Tobin, D. (1983)Learning Disabled

Gifted Children: identification and programming.

Baltimore, MD: University Park Press. Gagne, F. (1994) ‘Are teachers really poor talent

detectors? Comments on Pegnato and Birch’s (1959) study of the effectiveness and efficiency of various identification techniques’,Gifted Child Quarterly, 38 (3), 124–126.

Gear, G. H. (1978) ‘Effects of training in teacher accuracy in the identification of gifted children’,Gifted Child

Quarterly, 22 (1), 90–97.

Gross, M. (1993)Exceptionally Gifted Children. London: Routledge.

Gunderson, C. W., Maesch, C. & Rees, J. W. (1987) ‘The gifted/learning disabled students’,Gifted Child

Quarterly, 31 (4), 158–160.

Hanses, P. & Rost, D. H. (1998) ‘Das “Drama” der hochbegabten Underachiever – “gewöhnliche” oder “außergewöhnliche” Underachiever?’ [‘The “drama” of the gifted underachievers – “ordinary” or

“extraordinary” underachievers?’],Zeitschrift für Pädagogische Psychologie/German Journal of

Educational Psychology, 12, 53–71.

Hany, E. A. (1993) ‘How teachers identify gifted students: feature processing or concept based classification’,European Journal for High Ability, 4, 196–211.

Hany, E. A. (1997) ‘Modelling teachers’ judgments of giftedness: a methodological inquiry of judgement bias’,High Ability Studies, 8, 159–178.

Hany, E. A. (1998) ‘Cognitive abilities across the life span: results from a twin study spanning 55 years.’ Paper presented at the International Conference on Twin Research, Helsinki, Finland.

Hoge, R. D. & Cudmore, L. (1986) ‘The use of teacher-judgment measures in the identification of gifted pupils’,Teaching and Teacher Education, 2, 181–196.

Hornsby, B. (1994)The Hornsby Correspondence Course,

Module 1–4(fifth edition). London: The Hornsby

International Centre.

Hunsaker, S., Finley, S. & Frank, E. (1997) ‘An analysis of teacher nomination and student performance in gifted programs’,Gifted Child Quarterly, 41 (2), 19–24. Jacobs, J. C. (1971) ‘Effectiveness of teacher and parent

identification of gifted children as a function of school level’,Psychology in the Schools, 8, 140–142.

Landrum, T. J. (1989) ‘Gifted and learning disabled students: practical considerations for teachers’,

Academic Therapy, 24, 533–545.

Little, C. (2001) ‘A closer look at gifted children with disabilities’,Gifted Child Today, 24 (3), 46–54. Macfarlane, S. (2000) ‘Gifted children with learning

disabilities: a paradox for parents’ [online at http:// www.tki.org.nz/r/gifted/handbook/related/

disabilities_e.php].

Marland, S. P. (1972)Education of the Gifted and Talented

(Report to the subcommittee of education, Committee on Labour and Public Welfare, US Senate).

McBride, N. (1992) ‘Early identification of the gifted and talented students: where do teachers stand?’Gifted

Education International, 8 (1), 19–22.

McEachem, A. G. & Bornot, J. (2001) ‘Gifted students with learning disabilities: implications and strategies for school counselors’,Professional School Counseling, 5, 24–31.

Montgomery, D. (2000)Able Underachievers. London: Whurr Publishers.

Montgomery, D. (2003)Gifted and Talented Children with

Special Educational Needs: double exceptionality.

London: David Fulton.

National Association for Gifted Children (2001) ‘Gifted children with a learning difficulty’ [online at http:// www.64.233.183.104/search?q=cache:

BKBrwzYhU0QJ:teachertools.londongt.org/enGB/ resources/Gifted_children_with_a_learning_difficulty. doc+Gifted+Children+with+a+Learning+Difficulty+ NAGC&hl=en&ct=clnk&cd=8].

Ogilvie, E. (1973)Gifted Children in Primary Schools. London: Macmillan.

Ojanen, S. & Freeman, J. (1994)The Attitudes and Experi-ences of Headteachers, Class-Teachers, and Highly Able Pupils towards the Education of the Highly Able in

Finland and Britain. Savonlinna: University of Joensuu.

Porter, L. (1999)Gifted Young Child: a guide for teachers

and parents. Buckingham: Open University Press.

Powell, T. & Siegle, D. (2000) ‘Teacher bias in identifying gifted and talented students’,National Research

Center on the Gifted and Talented Newsletter,

13–15.

Reid, G. (1994)Specific Learning Difficulties (Dyslexia):

a handbook for study and practice. Edinburgh: Moray

House Publications.

Reis, S. M. (2000)Gifted Students with Learning

Disabilities.Communique. Washington, DC: National

Association for Gifted Children.

Rizza, M. G. & Morrison, W. F. (2003) ‘Uncovering stereotypes and identifying characteristics of gifted students and students with emotional/behavioral disabilities’,Roeper Review, (25) 2, 73–77.

Robinson, S. M. (1999) ‘Meeting the needs of students who are gifted and have learning disabilities’,

Intervention in School and Clinic, 34, 195–204.

Ruban, L. & Reis, S. (2005) ‘Identification and

assessment of gifted students with learning disabilities’,

Theory into Practice, (44) 2, 115–124.

Schiff, M. M., Kaufman, A. S. & Kaufman, N. L. (1981) ‘Scatter analysis of WISC profiles for learning disabled children with superior intelligence’,Journal of

Learning Disabilities, 14, 400–404.

Schrader, F. W. (1989)Diagnostische Kompetenzen von Lehrern und ihre Bedeutung für die Gestaltung und

Effektivität des Unterrichts. Frankfurt/Main: Lang.

Shaywitz, S. E. (1995) ‘A Matthew effect for IQ but not for reading: results from a longitudinal study’,Reading

Research Quarterly, 30, 894–906.

Siegle, D. & Powell, T. (2004) ‘Exploring teacher biases when nominating students for gifted programs’,Gifted

Child Quarterly, 48 (1), 21–92.

Silverman, L. K. (1983) ‘Personality development: the pursuit of excellence’,Journal for the Education of the

Gifted, 6 (1), 5–19.

Silverman, L. K. (1989) ‘Invisible gifts, invisible handicaps’,Roeper Review, 12, 37–42.

Sternberg, R. J. & Grigorenko, E. L. (2004) ‘Learning disabilities, giftedness, and gifted/LD’, in T. M. Newman & R. J. Sternberg (eds)Students with Both

Gifts and Learning Disabilities. New York: Kluwer.

Stewart, W. (2003) ‘The gifted and learning disabled student: teaching methodology that works’, in D. Montgomery (ed.),Gifted and Talented Children with

Special Educational Needs: double exceptionality.

London: David Fulton.

Stopper, M. J. (2000)Meeting the Social and Emotional

Needs of Gifted and Talented Children. London:

NACE/David Fulton.

Subhi, T. (1997) ‘Who is gifted? A computerised identifi-cation procedure’,High Ability Studies, 8 (2), 189–211. Tempest, N. R. (1974)Teaching Clever Children 7–11.

London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Terman, L. M. (1925)Genetic Study of Genius: Vol. 1. Mental and physical traits of a thousand gifted

children. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Turner, M. (1997)Psychological Assessment of Dyslexia

(first edition). London: Whurr Publishers.

Vaughn, S. (1989) ‘Gifted learning disability: is it such a bright idea?’Learning Disabilities Focus, 4 (2), 123–126.

Vialle, W. J. (2002) ‘Gifted profile: an interview with Eddie Braggett by Wilma Vialle’,Australasian Journal

of Gifted Education, 11 (1), 41–46.

Waldron, K. A., Saphire, D. G. & Rosenblum, S. (1987) ‘Learning disabilities and giftedness: identification based on self-concept, behavior, and academic patterns’,Journal of Learning Disabilities, 20, 422–427.

Wechsler, D. (1991)Wechsler Intelligence Scale for

Children(third edition). New York: Psychological Corp.

Whitmore, J. R. (1980)Giftedness, Conflict, and

Underachievement. Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Whitmore, J. R. & Maker, C. J. (1985)Intellectual

Giftedness in Disabled Persons. Rockville, MD: Aspen.

Willard-Holt, C. (1999)Dual Exceptionalities. Reston, VA: Clearinghouse on Disabilities and Gifted Education [online at http://www.ldonline.org/article/5888].

Address for correspondence:

Anies Al-Hroub

Department of Arts and Sciences American University of Beirut PO Box 11-0236

Beirut Lebanon

Email: anies.al-hroub@aub.edu.lb

Article submitted: December 2006 Accepted for publication: January 2008