FUNGAL ASSESSMENT OF SWEET YAM (Dioscorea esculenta) FLOUR Awah, N. S.1, 2, Agu, K. C.1 and Odoemena, A. C.1

Department of Applied Microbiology and Brewing

Nnamdi Azikiwe University, P. M. B. 5025, Awka, Anambra State

E-mail: [email protected] Mobile: +2348038728766 2To whom correspondence should be addressed

ABSTRACT

Sweet yam (Dioscorea esculenta) tubers were processed and fermented to the traditional West African dried yam flour. Yam slices were blanched for 10 minutes and left to ferment at room temperature for 48 hours. The fermented yam slices were oven dried at 50oC for 24 hours. The dried yam chips were ground into flour and 1g of the sample was serially diluted. Appropriate dilution was plated out in duplicate on Potato Dextrose Agar (PDA) prepared with added chloramphenicol to inhibit bacterial growth. Incubation of the culture plates was done at room temperature (35-37oC) for 4 to 5 days, which gave rise to a fungal count of 4×10-5 cfu/ml and 3×10-5 cfu/ml on plates A and B, respectively. A total of six isolates were recovered and characterized as species of Mucor, Rhizopus and Aspergillus with a percentage occurrence of 33.3%, 50% and 16.6%, respectively. The pH of the fermenting medium was reduced from 7.83 at the onset of fermentation to 4.65 at the end of fermentation.

INTRODUCTION

Sweet yam, Dioscorea species which are also grouped among the lesser yams are climbing plants with glaborous leaves and twining stems, which coil readily around a stake (1). It is an important source of carbohydrate for many people of the sub-region especially in the yam zone of West Africa (2). Yam is the second most important root/tuber crop in Africa after cassava (3). Sweet yam (Dioscorea esculenta) is one of the edible yams grown in Nigeria and some other countries along the west coast of Africa (4, 5). Probably because of its Asiatic origin (6), it is sometimes confusingly called Chinese yam in the West Indies and West Africa in place of Dioscorea opposita that is the true Chinese yam. Out of the World production of over 50 million tonne of yams per annum, Nigeria alone produces 35 million tonne. Despite this, the demand for yam tubers in Nigeria has always exceeded its supply. However, it has been that an average of over 25% of the yield is lost annually to diseases and pests (7, 8, 9).

Nigeria is the largest producer of yam in the world but there is no comprehensive account of the diseases of the crop (10). In order to minimize losses, considerable quantities of roots and tubers are transformed into more durable products by drying, fermentation and comminuted in different combinations and sequences producing a variety of material each with distinctive characteristics. In some West African countries such as Nigeria, Benin and Ghana, yams are processed into dry yam tubers/slices and flour (11, 12). When dry yam is milled into flour, called “elubo”, which is when stirred into boiling water makes a thick paste known as “amala” eaten with soup by the consumers (13, 12, 14). Hitherto, this age long traditional method is still being used for the processing of yam to dry yam (gbodo). Preliminary survey carried out on 263 processorsof the yams in South West Nigeria revealed that the local consumers have preference for the dry yams made by the Baruba or Baruten people of Kwara State who incidentally are the major producers of the traditional dry-yams (5). Though lesser yam is well adapted to the yam growing zones of Nigeria, it is largely consumed in local farmsteads and urban areas as boiled or fried yam, that is, without any other defined secondary or even tertiary food product from the starchy or carbohydrate rich edible tubers (16). The relatively short (sometimes about 2 months) shelf life of the harvested tubers at shaded tropical ambient condition (17) and the observed preference of the Nigerian yam consumers of the indigenous yam species (especially white Guinea yam or Dioscorea rotundata) over lesser yam in the preparation of local dishes (boiled and fried yam inclusive) seem to pose a very serious constraint to the crop’s expanded production in the country (18). Moreover, flours made with many white yam cultivars (and even some water yam or Dioscorea alata genotypes) serve as secondary products for the preparation of locally cherished amala and yam fufu meals (19). Early research work in the West Indies showed that D. esculenta flour was among those that gave stiff dough for bread making (20, 21).

quantities as a fresh vegetable but a large proportion is processed mainly at the level into dried products (12). The need for processing is due largely to extreme perishability and storage losses as a result of decay and rotting (22).

MATERIALS AND METHODS Preparation of Raw Materials

Sweet yam tubers (Dioscorea esculenta) were obtained from a local market in Uyo, Akwa Ibom State. The yam tubers were thoroughly washed with clean water to remove adhering soil and other undesirable materials and to reduce microbial growth on the final product. The yam tubers were peeled, washed, cut into uniform size and mixed in the ratio of 1:2 with water. They were blanched for 10 minutes. Thereafter, the mixture was allowed to cool and ferment for two days at room temperature. The pH of the medium was monitored during the fermentation period. After fermentation, the water used for the fermentation was decanted and the yam slices dried in a hot air oven at 50oC for 24 hours. The dried chips were then ground with an electric blender and the flour obtained stored in a sterile polythene bag.

MEDIA PREPARATION

The medium used was potato Dextrose agar (PDA) prepared by dissolving 20g of D(+) glucose and 15g of agar-agar in a potato infusion from 200g of Irish potatoes. The solution was blanched for 10minutes to enhance the dissolution of the solutes in the solvent. Chloramphenicol (50mg/ml ethanol) was added to the solution to inhibit any bacterial growth. The medium was then sterilized by autoclaving at 121oC for 15minutes at 15p.s.i and allowed to cool before pouring carefully into sterile Petri dishes.

PROCESSING OF YAM FLOUR

One gram of the yam flour was used to prepare a tenfold serial dilution. The diluent used for the dilution contained 0.5g of sodium chloride and 1g of bacteriological peptone dissolved in 100ml of distilled water and sterilized by autoclaving at 121oC for 15minutes. Thereafter, 0.1ml of the 10-5 dilution was plated on potato dextrose agar (PDA). The plates were then incubated at room temperature for 72hours.

ISOLATION AND IDENTIFICATION OF MICROORGANISMS

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The result of pH readings during the fermentation of sweet yam slices are presented in Table 1. There was a progressive reduction in the pH value from 7.83 at the onset of fermentation to 4.65 at the end of the 48th hour fermentation period. The reduction in pH of the fermentation medium can be attributed to the actions of microorganisms involved in medium. Microorganisms, during fermentation process produce acids and other metabolites through its various metabolic activities thereby reducing the pH of the fermentation medium.

The results of the fungal counts from the fermented sweet yam flour are depicted in Table 2. The duplicate plates A and B recorded a total fungal count of 4.0 x 10-5 cfu/ml and 3.0 x 10-5 cfu/ml, respectively giving an average fungal count of the two plates as 3.5 0 x 10-5 cfu/ml. The low fungal count obtained in this study can be attributed to the attributed to the process of subjecting the fermented sweet yam chips to drying (25). This process of subjecting any food substance to heat treatment is a general or normal way of sterilizing food substances thereby reducing their microbial loads (26).

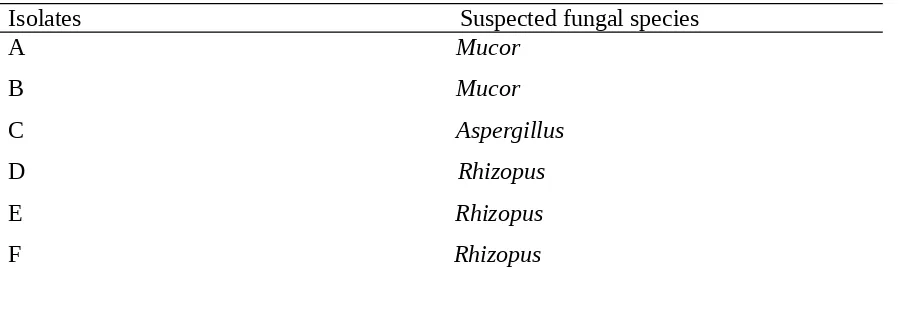

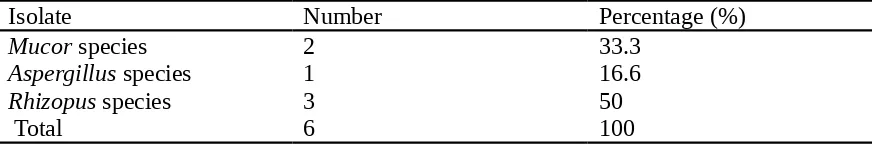

The microscopic and macroscopic characteristics of the fungi isolated from fermented sweet yam are depicted in Table 3 while the percentage occurrences of the isolates are presented in Table 4. A total of six isolates were obtained and purified as species of Mucor, Aspergillus and Rhizopus with relative occurrence of 33.3%, 16.6% and 50%, respectively. These fungi may have been present in the atmosphere in the form of spores as reported by (25). These fungi were not different from the earlier reports of mycoflora of sweet yam (25). However in this study, yeast species such as Candida, Geotrichium and Pichia were not detected. Perhaps due to the available nutrients and prevailing environmental conditions that determines the nature and density of the colonizers. Fungi isolates of dried yam flour isolated were identified based on their microscopic and macroscopic characteristics and a further comparison with the specimens in the atlas (23, 24).

TABLE 1: pH Levels of the Fermentation Medium of Sweet Yam

Fermentation Period (h) pH Level

0 7.83

24 6.45

[image:6.612.87.530.194.256.2]48 4.65

TABLE 2: Total Fungal Count Observed After the First Culture Process

Plate Count Total Count (cfu/ml)

A 4 4×10-5

B

Average 33 3×10

-5 3.5×10-5

Table 3: Fungal Isolates from Sweet Yam Flour

Isolates Suspected fungal species A Mucor

[image:6.612.86.538.295.460.2]TABLE 4: Frequency distribution of the isolates from the yam flour

Isolate Number Percentage (%)

Mucor species 2 33.3

Aspergillus species 1 16.6

Rhizopus species 3 50

CONCLUSION

REFERENCES

1. Udensi, E. A., Oselebe, H. O. and Iweala, O. O. (2008). The investigation of

chemical composition and functional properties of water yam (Dioscorea alata): Effect of varietal differences. Pakistan Journal of Science, 7: 342-344

2. Akissoe, N. H., Hounhouigan, J. D., Bricas, N., Vernier, P., Nago, M. C. and Olurunda, O. A. (2001). Physical, chemical and sensory evaluation of evaluation of dried yam (Dioscorea rotundata) tubers, flour and amala flour derived product. Tropical Science, 41: 151-156

3. Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) (1997).Food Production Yearbook, Volume 50

4. Akoroda, M. O. and Hahn, S. K. (1995). Yams in Nigeria: Status and trends. African Journal of Root and Tuber Crops, 1(1): 38-41

5. Raemaekers, R. H. (2001). Crop production in tropical Africa, DGIC, Brussels, Belgium

6. Hahn, S. K. (1995). Yams: Dioscorea spp. (Dioscoreaceae), In’ Evolution of crop plants, Smart, J. and Simmonds, N. W. (eds), Longman Scientific and Technical, London,pp 112-120

7. Arene, O. B. (1987). Advances integrated control of economic diseases of cassava in Nigeria. In: Integrated Pest Management for Tropical Roots and Tubers Crops, Hahn, S. K. and Cavenes, F. E. (eds), pp. 167-175 8. Ezeh, N.O. (1998). Economics of production and post-harvest Technology, In: Advances in research, Orkwor. G. C., Asiedu, R. and Ekanayake, I. J. (eds), IITA and NRCRI, Ibadan, Nigeria, pp 187-214

9. Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) (1998).Storage and Processing of roots and tubers in the tropics.

10. Amusa, N. A. and Baiyewu, R. A. (1999). Storage and market disease of yam tubers in south western Nigeria, Ogun. Journal of Agricultural Resource (Nigeria), 11: 211-225

11. Bricas, N., Vernier, P., Ategbo, E., Hounhouigan, J. Mitchekpe, E., Nkpenu, K. and Orkwor, G. (1997). Le development La Filiere cossettes d'Igname en Afrique de L'Quest. Cashiers de la recherche' Development, 44(2): 100-114 12. Achi, O. K. and Akubor, P. I. (2000). Microbiological characterization

13. Akingbala, J. O., Oguntimein, T. B., and Sobanda, A. O. (1995).

Physico-chemical properties and acceptability of yam flour substituted with Soy flour. Plant Food for Human Nutrition, 48: 73-80

14. Akissoe, N. H., Hounhouigan, J. D., Bricas, N., Vernier, P., Nago, M. C. and Olurunda, O. A. (2001). Physical, Chemical and Sensory Evaluation of dried yam (Dioscorea rotundata) Tubers Flour and Amala- A

Flour Derived Product. Tropical Science, 41: 151-156

15. Babajide, J. M., Oyewole, O. B. and Obadina, O. A (2005). An assessment of the microbiological safety of dry yam (gbodo) processed in western Nigeria, African Journal of Biotechnology, 5(2): 157-161

16. Degras, L. (1993). The yam, a Tropical Root Crop, Macmillan Press, London. Pp 1-404

17. Opara, L.U. (1999). Post-Harvest Operation: Chapter XXIV Yams. 18. Ukpabi, U. J. (2010). Fermented breadmaking potential of lesser yam

(Dioscorea esculenta) flour in Nigeria. Australian Journal of Crop Science, 4(2): 68-73

19. Ukpabi, U. J. and Omodamiro, R. M. (2008). Assessment of hybrid

white yam (Dioscorea rotundata) genotypes for the preparation of Amala. Nigerian Food Journal, 26(1): 111-118

20. Martin, F. W. (1974). Tropical yams and their potential. Part 1. Dioscorea esculenta. Agricultural Handbook No. 457, USDA, Washington D.C. pp 18

21. Martin, F. W. and Ruberte, R. (1975). Flours made from edible yams

(Dioscorea spp.) as substitute for wheat flour. Journal of Agricultural for University of Peutro Rico, 59(4): 255-263

22. Coursey, D. G. (1967). Yam storage 1. A review of storage practices and information on storages losses. Journal of Stored Product Research, 2: 227-244

23. Bulmer, G. S. (1978). Medical Mycology, Airborne fungi, UpJohn Company, Michigan, pp78-91

24. Frey, D., Oldfield R.J. and Bridger, R.C. (1979). A color atlas of pathogenic fungi,Wolfs, Medical Publisher. pp 83-93

25. Okigbo, R.N and Nwakammah, P.T., (2005). Biodegradation of white yam (Dioscorea rotundata Poir) and water yam (Dioscorea alata L.) slices dried

26. Rozis, J.F. (1997). Drying Food Stuffs. Backhugs Publisher Leiden. pp 311. 27. Babajide, J. M., Oyewole, O. B., Henshaw, F.O., Babajide, S. O. and

Olasantan, A. O. (2006). Effect of local preservatives on quality of traditional dry yam slices “Gbodo” and its products. World Journal of Agricultural Sciences, 2(3): 267-273