Effect of hormone replacement therapy on age-related increase in

carotid artery intima-media thickness in postmenopausal women

Florence A. Tremollieres *, Fabienne Cigagna, Cathy Alquier, Colette Cauneille,

Jean-Michel Pouilles, Claude Ribot

Menopause and Metabolic Bone Diseases Unit,Department of Endocrinology,CHU Rangueil,1,a6enue Jean Poulhes,

31403Toulouse Cedex 4,France

Received 29 July 1999; received in revised form 8 November 1999; accepted 16 December 1999

Abstract

The aim of this study was to determine the changes in carotid artery intima-media thickness as measured by B-mode ultrasound in postmenopausal women receiving hormone replacement therapy (HRT) or not. One hundred and fifty-nine healthy post-menopausal women aged 45 – 65 years were recruited from our menopause clinic. All the selected women were free of cardio-vascular diseases and had no cardio-vascular risk factors. None of the women were receiving lipid-lowering or antihyper-tensive drugs. Because carotid artery intima-media thickness was shown to be strongly and positively correlated with age in women aged 55 years and older but not before, women were divided into four groups according to age (B55 vs.]55 years) and use of HRT (current users vs. never users). All the treated women received non-oral 17b-estradiol with a non-androgenic progestin and had started HRT within the first year after menopause. Scanning of the right common carotid artery was performed with a B-mode ultrasound imager and thickness of the intima-media complex as well as luminal diameter of the artery were determined using an automated computerized procedure. Within each age group (i.e. B55 or ]55 years), women had comparable demographic characteristics and only differed by HRT use. Long-term treated women had significantly lower total cholesterol levels than untreated women (P=0.005). Triglycerides, low-density lipids (LDL)-cholesterol and high-density lipids (HDL)-cholesterol levels, systolic and diastolic blood pressure were not significantly different between users and non-users. In women

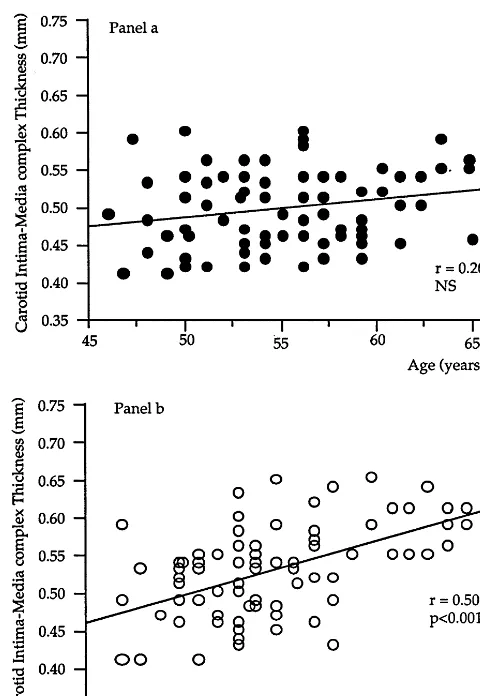

B55 years, no significant difference in carotid intima-media thickness was found between current users (mean 2.591.4 years) and non users. In older women, the mean values of carotid intima-media thickness were significantly smaller in current users (mean 6.993.3 years) than in never treated women: 0.5090.05 versus 0.5690.07 mm, PB0.0001. Carotid artery intima-media thickness was significantly correlated to age in never users (r=0.5,PB0.0001) but not in women who were currently receiving HRT (r=0.2, ns). These findings suggest an apparent protective effect of long-term HRT on age-related thickening of the intima-media of the right common carotid artery. This may contribute to explain the apparent cardio-protective effect of HRT after the menopause. © 2000 Elsevier Science Ireland Ltd. All rights reserved.

Keywords:Hormone replacement therapy; Menopause; Intima-media thickness; B-mode ultrasound

www.elsevier.com/locate/atherosclerosis

1. Introduction

Coronary heart diseases are the leading causes of death in most industrialized countries. Several epidemi-ological studies have reported that during their repro-ductive years women are relatively protected against coronary atherosclerosis and that menopause, especially in case of surgical menopause, is associated with a loss

of protection [1 – 4]. Numerous in vitro and animal investigations as well as epidemiological and clinical studies [5,6] have reported a cardioprotective effect of estrogen replacement therapy, although it is still ques-tionable to what extent postmenopausal estrogen use is associated with a reduction in coronary events [7]. The beneficial effect of estrogen on coronary heart disease has been attributed to positive changes in different serologic markers such as lipid and lipoprotein profile [8,9], glucose tolerance [10] or haemostatic factors [11,12]. However, estrogens also have direct effects on

Presented at the 80th Annual Meeting of the Endocrine Society, New Orleans, USA, June 24 – 27, 1998.

* Corresponding author.

the arterial wall [13] and these direct effects both on the vasoreactivity [14 – 16] and the progression of coronary artery atherosclerosis [17] are thought to account for most of the cardioprotective effect of estrogens.

It is currently possible using B-mode ultrasonogra-phy to assess the early stages of the atherosclerotic process in the carotid arteries [18 – 20]. Thickening of intima-media is currently considered as the earliest marker of generalized atherosclerosis and has been associated with an increased risk of coronary artery disease [21 – 24]. Therefore, the aim of this study was to determine whether hormone replacement therapy was associated with changes in intima-media thickness as measured by B-mode ultrasound in postmenopausal women.

2. Subjects and methods

2.1. Subjects

One hundred and fifty-nine healthy postmenopausal women aged 45 – 65 years were selected from those who attended our menopause clinic for a routine health check throughout a 6-month period between July and December 1997. Normality was assessed through inter-view and after extensive physical and biochemical ex-aminations according to a procedure previously reported [25,26]. In particular, all women answered a computer-assisted questionnaire that was recorded by the same-trained research nurse. This questionnaire comprised a total of 156 items, including medical his-tory, reproductive hishis-tory, medication use (including use of hormone replacement therapy), level of physical activity, alcohol and tobacco intake as well as other variables. Seventy-two questions were exclusively re-lated to the identification of familial and personal car-dio-vascular risk factors [27]. For this study, only women with no cardiovascular risk factors were consid-ered. This also included past or current history of coronary heart disease (including myocardial infarction, stroke or peripheral arteriopathy). Blood pressure was measured using an automated sphingomanometric pro-cedure after subjects had been resting for at least 5 min. The average of two measurements at 5 min was consid-ered. None of the selected women had ever taken any antihypertensive treatment and all of them had blood pressure B140/90 mmHg. None of the women smoked or had ever smoked and all of them had an alcohol intake B45 g of alcohol per week. A physical activity questionnaire assessed self-reported activity at home, at work and during leisure time [28]. A summary activity score was used in this analysis and all women included in this study were classified in the light activity category (i.e. when their score was the equivalent of 1 – 3 h of walking per day). Body mass index (weight per height

squared) was used to measure excess weight and women with a body mass index (BMI)\30 kg/m2 were ex-cluded. Blood lipids including total cholesterol, triglyce-rides, low-density (LDL) and high-density (HDL) lipoproteins were measured in all women after an overnight fast. All women included in this study had serum total cholesterol levels below 250 mg/dl associ-ated with serum LDL-cholesterol below 160 mg/dl, triglycerides levels below 150 mg/dl and HDL-choles-terol levels \50 mg/dl. Likewise, none of the selected women had ever used lipid-lowering drugs. All women also had fasting serum glucose levels B10 mmol/l. Finally, additional exclusion criteria included history of premature menopause below the age of 40 years.

All women had passed the menopause as confirmed by an amenorrhea period of at least 12 months associ-ated with serum FSH levels above 30 IU/ml and serum estradiol levels below 20 pg/ml. They were divided into two groups according to the use of hormone replace-ment therapy (HRT):

Eighty-six women were currently receiving hormone

replacement therapy and all the women had started estrogen therapy within the first year after menopause. All of them were receiving non-oral estrogen: 44 women were receiving 1.5 mg/day of 17b-estradiol as percutanous gel and 42 women used a transdermal system delivering 50 mg/day of 17b -estradiol that was changed twice a week, 25 days a month. Estrogen therapy was given in all women in combination with natural progesterone or a 19-nor progesterone derivative.

Seventy-two, women with similar clinical

characteris-tics to treated women, who had never used HRT served as controls.

We had previously determined in a population of 380 healthy women aged 40 – 80 years, not receiving sex hormone therapy and free of cardio-vascular risk fac-tors, that IMC thickness was significantly correlated to age and was best described by a 2-order polynomial function of age (personal results). Therefore and be-cause IMC thickness was found not to significantly change up to the age of 55 years and to significantly increase thereafter, changes in IMC thickness between treated and never treated women were examined into two age-classes: B55 years and ]55 years.

2.2. Arterial measurements

time on a monitor and the sound beam was adjusted perpendicularly to the arterial surface of the far wall of the vessel in order to obtain two parallel echogenic lines corresponding to the lumen-intima and media-adventi-tia interfaces. These two lines defined the intima-media complex (IMC) of the far wall of the vessel [19,20]. Once the IMC was clearly visible along at least 1 cm of the arterial segment, the ‘frozen’ end-diastolic (electro-cardiographic R-triggering) image was transferred on a computer (Apple Macintosh). The image was stored and analyzed off-line. In each woman, two successive measurements of the same arterial segment were per-formed and the average value was considered in each subject. The total procedure time excluding time for analysis averaged 10 min per subject.

2.3. Analysis of intima-media complex thickness and arterial diameter

Analyses were performed with an appropriate pro-gram (Iotec system, Ioˆ Data Processing Co, Paris, France) which is based on the analysis of gray level density and on specific tissue recognition algorithms as previously described [29,30]. Briefly, the image is transferred from the storage memory mass of the computer and represented at 4.8-fold magnification of the anatomic structure. A field of measure in-cluding the IMC of the far wall was chosen by the examiner who automatically drew a rectangle of at least 1 cm long in the longitudinal axis of the vessel and 0.3 cm high in the direction perpendicular to the wall. The computer discriminates change in grey level inside the field of measure and locates the two interfaces (lumen-intima and media-adventitia) repre-senting the IMC. The IMC thickness is measured every 10mm along at least 1 cm of the length of artery and the average thickness represents the mean of at least 100 successive measures. The internal lumen di-ameter of the artery is automatically measured along the same distance as the IMC and represents the aver-age distance between the near and far lumen-intima interfaces.

Histological validation of IMC measurements using this method has been previously reported [29]. The reproducibility of measurements was performed in 13 healthy volunteers by repeating the ultrasonographic assessment five times over a 15-day period of time. The reproducibility was defined as the variation coefficient between the five repeated measures and was 4.591.7% for carotid IMC thickness and 3.191.4% for carotid diameter.

2.4. Laboratory assays and measurements

Plasma total cholesterol, triglycerides and HDL-cholesterol concentrations were determined by an

enzy-matic technique using a Hitachi 717 multiparametric analyzer (using the Boehringer Mannheim reactants, Boehringer Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany), the lat-ter in the supernatant aflat-ter precipitation with the ion-ized magnesium-dextran sulfate precipitation technique. The cholesterol content of LDL-cholesterol lipoproteins was estimated according to the procedure of Friede-wald et al. [31]. Total estradiol (E2) and serum follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) concentrations were measured by RIA (Clinical Assays, Sorin Biomedica) and by IRMA (I125-hFSH COATRIA, Bio-Me´rieux, Lyon, France), respectively.

2.5. Statistical analysis

Analyses were performed using the Statview F-4.5/ SuperAnova Macintosh package. Differences within each age-subgroup (i.e. in women B55 years and in women ]55 years) were examined by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and significance level was set at PB0.05. Correlations were performed by least-squares regression. Comparison of the regression slopes between groups was made by analysis of covari-ance (ANCOVA). When adjustment for covariates (i.e. total cholesterol and triglycerides levels) was re-quired, comparisons were performed by ANCOVA analysis.

3. Results

3.1. General characteristics and biological 6ariables

Since we had previously determined in a large group of normal untreated women that IMC thickness was significantly and positively correlated with age only in women aged 55 years and older but not before, com-parisons between treated and untreated women were performed according to an age more or B55 years. The general characteristics of the population are shown in Table 1. Within each age group, women had similar characteristics and only differed by use of HRT. On average, women in the ]55 year-group were 7 years older. In the young age group, treated women were receiving HRT for a mean 2.591.4 years, while in the older age group the mean duration of treatment was 6.993.3 years.

statisti-cally different between HRT users and non-users within the two age groups.

3.2. Carotid IMC thickness, lumen diameter and HRT

Overall, mean carotid IMC thickness was 0.5090.05 mm in the HRT group compared to 0.5490.06 mm in age-matched controls (P=0.0001). In women B55 years of age both IMC thickness and mean lumen diameter were not significantly different in those on HRT as compared to controls (Table 3). However, in women aged 55 years or more, mean carotid IMC thickness, but not mean lumen diameter, was signifi-cantly smaller in HRT users than in non users (PB

0.0001, ANOVA).

3.3. Carotid IMC thickness and HRT and age

In Fig. 1, carotid IMC thickness was plotted against age in the two groups of treated and never treated women. In untreated women, carotid IMC thickness was significantly correlated to age (r=0.50, PB0.001). On the other hand, in treated women this correlation between IMC thickness and age no longer existed and the slope of the correlation was not significantly different from zero (r=0.2, ns) and significantly different from that in never treated women (PB0.001). In treated women, IMC thickness was correlated, although not signifi-cantly, to the duration of treatment (r=0.207, P= 0.062).

Table 1

Clinical characteristics of the population

]55 years

B55 years

Treated (n=41) Untreated (n=35)

Treated (n=41) Untreated (n=42)

58.793.1

51.792 5192.3 58.893.3

Age (years)

56.597.2

59.798.5 56.296.9* 58.296.4

Weight (kg)

158.595 15996

15995* Height (cm) 16297

2392.8 22.592.7

22.792.8

BMI (kg/m2) 22.392.6

2.491.5

YSM (years)a 391.5 6.694 7.593.4

HRT (years) – 2.591.4 – 6.993.3

aYSM: years since menopause.

*PB0.05.

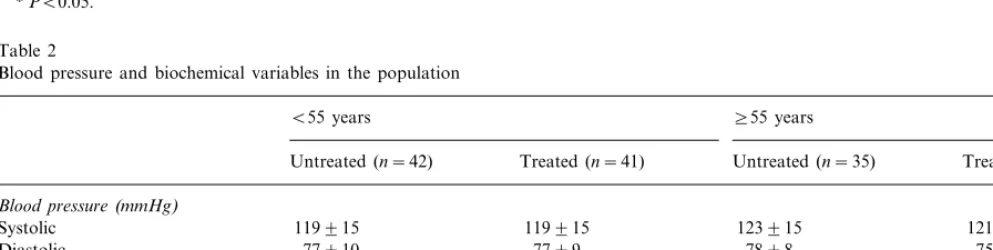

Table 2

Blood pressure and biochemical variables in the population

B55 years ]55 years

Treated (n=41) Treated (n=41)

Untreated (n=42) Untreated (n=35)

Blood pressure(mmHg)

119915 119915 123915

Systolic 121915

7599 7898

7799

Diastolic 77910

2.390.3 2.190.3 2.590.35 2.290.3*

Total cholesterol (g/l)

1.390.3 LDL-cholesterol (g/l) 1.390.3 1.290.3 1.590.4

HDL-cholesterol (g/l) 0.890.1 0.890.2 0.7590.1 0.790.1

Triglycerides (g/l) 0.8690.4 0.7690.3 0.8990.5 0.8190.3

*PB0.005.

Table 3

B55 years ]55 years

Treated (n=41)

Untreated (n=42) Untreated (n=35) Treated (n=41)

0.5190.05

IMT (mm) 0.4990.05 0.5690.07 0.5090.05*

Lumen diameter (mm) 5.6290.5 5.4890.4 5.8390.6 5.6290.5

HRT (years) – 2.591.4 – 6.993.3

Fig. 1. Correlations between carotid artery intima-media thickness and age in women receiving HRT (panel a) and never treated control women (panel b). The slopes of the correlation were significantly different (PB0.001) in treated women (r=0.20, ns) as compared to never treated women (r=0.50,PB0.001).

receiving hormone replacement therapy. We found that the mean value of IMC thickness of the far wall of the right common carotid artery was significantly thinner in long-term treated women as compared to age-matched, never treated women. The fact that IMC thickness was only found to be thinner in women who had been receiving HRT for an average of 7 years, but not in women treated for a shorter period of time, suggests that a long duration of HRT use is necessary to affect carotid artery thickness. These findings are in agree-ment with those of McGrath et al. [32] who found that IMC thickness was not significantly different in women

560 years of age on HRT as compared to controls, while in women \60 years of age, those who were on HRT had a significantly lower mean IMC thickness. It is well known that IMC thickness significantly in-creased with age and in the ACAPS [33] and ARIC [34] studies the reported annual rates of progression of IMC thickness for women aged 50 – 80 years were 0.015 – 0.02 mm per year. Interestingly, in our study the IMC thickness-age relationship appeared to be influenced by HRT with the difference in IMC thickness between treated women and controls increasing with age, be-cause the observed effects of HRT were more marked in older women. Accordingly, HRT appears to out-weigh the effect of aging on the carotid wall which could contribute to explain the beneficial effect of HRT on coronary heart disease. Numerous studies have doc-umented the cardioprotective effect of estrogen therapy [5 – 7], although it is still questionable to what extent estrogens are associated with a reduction in coronary events. Moreover, recent data from the HERS study [35] indicate that the cardioprotective effect of HRT might have been overestimated at least in women with existing coronary heart disease. Whether these results could be extrapolated to healthy women remains to be determined from long-term controlled trials such as the Women’s Health Initiative.

Estrogens are likely to exert their protective effect through beneficial changes in serologic markers (i.e. lipid and lipoprotein metabolism, glucose tolerance, and coagulation factors...) but also through a direct action on the arterial wall [13 – 17]. In our study, IMC thickness was significantly correlated to both total cholesterol and triglycerides levels, raising the question as to whether the thinner IMC thickness observed in long-term treated women could be related to a better lipid profile than in never treated women. Accordingly, treated women had significantly lower total cholesterol levels as compared to age-matched untreated controls. However, even after adjustment for this lipid marker, treated women had still thinner IMC thickness as com-pared to never treated women, suggesting that changes in carotid thickness might reflect in part a direct effect of estrogen on the vessel wall structure.

3.4. Carotid IMC thickness and HRT and blood lipids

When all subjects were analyzed together, positive correlations existed between IMC thickness and both total cholesterol (r=0.18, PB0.05) and triglycerides (r=0.18, PB0.05) levels. IMC thickness values were thus adjusted for these two lipid variables and differ-ences according to HRT use were determined within the two age groups. In the same way as what was found for unadjusted IMC thickness values, the between-group differences in mean IMC thickness remained significant after adjustment for cholesterol and triglycerides levels only in the older age-group (PB0.05).

4. Discussion

Recently, ultrasonographic methods have been developed to visualize the arterial wall and monitor the early stages of the atherosclerosis process [18 – 20]. Thickening of the carotid artery intima-media is gener-ally considered to be an early marker of coronary atherosclerosis because it has been associated with un-favorable risk factors profile [36,37], other localization of atherosclerosis [23,38] and ultimately, increased risk of myocardial infarction [21 – 24]. One of the major advantages of this measurement is that it provides direct information about the progression of atheroscle-rosis at the level of the arterial wall in each patient, independently of traditional risk factors. However, some limitations remain, mainly related to the method-ology used to assess the arterial thickness, its accuracy and precision, but also the arterial site where it is measured. These explain why it remains currently difficult to compare results from studies using different measurement methods.

To date, few studies, all of cross-sectional design, have examined the effects of estrogen replacement ther-apy on changes in carotid artery wall thickness with sometimes, discordant results. Different investigations [31,39,40] performed in women older than 60 years reported lower adjusted carotid IMC thickness of the common carotid in current long-term estrogen users, as compared to never treated women. In a 3-year study, Espeland et al. [33] reported that HRT was found to halt progression of atherosclerosis. In another report [41] in younger postmenopausal women, mean intima thickness was also found to be thinner in women who were receiving HRT, although the media layer was found to be thicker as compared to untreated controls. In our study, the ultrasonic technique does not allow the discrimination of the intimal and medial contribu-tions to the thickening process, thus a direct compari-son with these data cannot be done. However, in the study of Muscat Baron et al. [41], because of the limited penetration of the ultrasound waves permitted by the high frequency of the probe, measurements were per-formed at the point of strongest pulsation of the left carotid artery. It is therefore possible that this arterial segment was more subject to hemodynamic turbulence that could have led to physiological changes in wall thickness, independently of estrogen action. On the other hand, in a large cross-sectional study [42], no association between carotid intima-media thickness and use of postmenopausal estrogen was found in 2385 women, 384 of whom were currently receiving estrogen replacement therapy. However, treated women differed from untreated women with regard to cardio-vascular risk factors; in particular previous use of oral contra-ceptives was found to be associated with higher wall thicknesses. Also, details on hormone formulations and doses were not available, which may have limited the validity of their conclusions. In our study, menopausal

status as well as the nature and dose of treatment regimens were very well characterized. Interestingly, all women received non-oral estrogens, which would sug-gest that this route of estrogen administration is also likely to be associated with a beneficial effect on the vascular wall. It can be noted that Gangar et al. [14] had previously reported that transdermal estrogen had a positive effect on the vascular tone. Nevertheless and as in previously reported studies, one of the limitations of the present study is its cross-sectional nature, which could not allow a robust examination of the effect of HRT on the progression of carotid atherosclerosis. It is unlikely however, that the nature of the patient selec-tion process may have interfered with these results. Indeed, measurement of intima-media thickness is in-cluded in a larger ‘menopause check-up’ and is system-atically performed in all women who are referred to our menopause clinic, one of the main reasons being the evaluation of the risk of osteoporosis. Moreover, all women were in good health and all of them were free of overt cardiovascular disease as well as of traditional cardiovascular risk factors that could have confounding effects of arterial wall changes. Finally, the mean IMC thickness value in the control group was not signifi-cantly different from that determined in our normal reference population of the same age. It is therefore unlikely that the difference in IMC thickness observed between controls and treated women might have been related to higher values than normal in the control group.

In summary, the findings of this cross-sectional study conducted in a large sample of healthy postmenopausal women suggest an apparent protective effect of long-term HRT on age-related thickening of the intima-me-dia of the right common carotid artery. This effect might contribute to explain the apparent cardioprotec-tive effect of HRT. Further longitudinal studies are however needed to confirm this effect and to determine to what extent these changes in carotid arterial intima-media thickness are predictive of coronary events in postmenopausal women receiving HRT. In any case, ultrasound measurement of intima-media thickness is likely to represent a valuable tool to monitor the effect of hormone replacement therapy on carotid atheroscle-rosis progression in postmenopausal women.

References

[1] Gordon T, Kannel WB, Hjortland MC, McNamara PM. Menopause and coronary heart disease: the Framingham study. Ann Intern Med 1978;89:157 – 61.

[2] Colditz GA, Willet WC, Stampfer MJ, Rosner B, Speizer FE, Hennekens CH. Menopause and the risk of coronary heart disease in women. N Engl J Med 1987;316:1105 – 10.

[4] Van der Schouw Y, Van der Graaf Y, Steyerberg EW, Eijke-mans MJC, Banga JD. Age at menopause as a risk factor for cardiovascular mortality. Lancet 1996;347:714 – 8.

[5] Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Willet WWC, et al. Postmenopausal estrogen therapy and cardiovascular disease: 10-year follow-up from the Nurses Health Study. N Engl J Med 1991;325:756 – 62.

[6] Grady D, Rubin SM, Petitti DB, et al. Hormone therapy to prevent diseases and prolong life in postmenopausal women. Ann Intern Med 1992;117:1016 – 37.

[7] Lindsay R, Bush TL, Grady D, Spearoff L, Lobo RA. Estrogen replacement in menopause. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1996;81:3829 – 38.

[8] The Writing Group for the PEPI trial. Effects of estrogen or estrogen/progestin regimens on heart disease risk factors in postmenopausal women; the postmenopausal estrogen/progestin interventions (PEPI) trial. J Am Med Assoc 1995;273:199 – 208.

[9] Kim CJ, Ryu WS, Kwak JW, Park CT, Ryoo UH. Changes in Lp(a) lipoprotein and lipid levels after cessation of female sex hormone production and estrogen replacement therapy. Arch Intern Med 1996;156:500 – 4.

[10] Godsland IF, Gangar KF, Walton C, et al. Insulin resistance, secretion and elimination in postmenopausal women receiving oral or transdermal estrogen replacement therapy. Metabolism 1993;42:846 – 53.

[11] Notelevitz M, Kitchens C, Ware M, Irschberg K, Coone L. Combination estrogen and progestogen replacement therapy does not adverselly affect coagulation. Obstet Gynecol 1983;62:596 – 600.

[12] Scarabin PY, Alhenc-Gelas M, Plu-Bureau G, Taisne P, Agher R, Aiach M. Effects of oral and transdermal estrogen/ proges-terone regimens on blood coagulation and fibrinolysis in post-menopausal women. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 1997;17:3071 – 8.

[13] Mendelsohn ME, Karas RH. The protective effects of estrogen on cardiovascular system. New Engl J Med 1999;340:1801 – 11. [14] Gangar KF, Vias S, Whitehead MI, Crook D, Miere H,

Camp-bell S. Pulsatility index in the internal carotid artery is influenced by transdermal estradiol and time since menopause. Lancet 1991;338:839 – 42.

[15] Liebermann EH, Gerhard MD, Uehata A, et al. Estrogen im-proves endothelium-dependent, flow mediated vasodilatation in postmenopausal women. Ann Intern Med 1994;121:936 – 41. [16] Arora S, Veves A, Caballaro AE, Smakowski P, LoGerfo FW.

Estrogen improves endothelial function. J Vasc Surg 1998;27:1141 – 6.

[17] Adams MR, Kaplan JR, Manuck SB, et al. Inhibition of coro-nary artery atherosclerosis by 17-beta estradiol in ovariectomized monkeys: lack of an effect of added progesterone. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 1990;10:1051 – 7.

[18] Pignoli P, Tremoli E, Poli A, Oreste PL, Paoletti R. Intimal plus medial thickness of the arterial wall: a direct measurement with ultrasound imaging. Circulation 1986;74:1399 – 406.

[19] Persson J, Stavenow L, Wikstrand J, Israelsson B, Formgren J, Berglund G. Noninvasive quantification of atherosclerotic le-sions. Arterioscler Thromb 1992;12:261 – 6.

[20] Salonen JT, Salonen R. Ultrasound B-mode imaging in observa-tional studies of atherosclerotic progression. Circulation 1993;87:56 – 65.

[21] Craven TE, Ryu JE, Espeland MA, et al. Evaluation of the associations between carotid artery atherosclerosis and coronary artery stenosis. Circulation 1990;82:1230 – 42.

[22] Salonen JT, Salonen R. Ultrasonographically assessed carotid morphology and the risk of coronary heart disease. Arterioscler Thromb 1991;11:1245 – 9.

[23] Hulthe J, Wikstrand J, Emanuelsson H, Wiklund O, DeFeyter PJ, Wendelhag I. Atherosclerotic changes in the carotid artery

bulb as measured by B-mode ultrasound are associated with the extent of coronary atherosclerosis. Stroke 1997;28:1189 – 94. [24] Hodis H, Mack WJ, LaBree L, et al. The role of carotid arterial

intima-media thickness in predicting clinical coronary events. Ann Intern Med 1998;128:262 – 9.

[25] Ribot C, Tre´mollieres F, Pouilles JM, Louvet JP, Guiraud R. Influence of the menopause and aging on spinal density in French women. Bone Mineral 1988;5:89 – 95.

[26] Ribot C, Bonneu M, Pouilles JM, Tre´mollieres F. Assessment of the risk of postmenopausal osteoporosis using clinical factors. Clin Endocrinol 1992;36:225 – 8.

[27] Tre´mollieres FA, Pouilles JM, Cauneille C, Ribot C. Coronary heart disease risk factors and menopause: a study in 1684 French women. Atherosclerosis 1999;142:415 – 23.

[28] Paffenbarger RS, Wing AL, Hyde RT. Physical activity as an index of heart attack risk in college alumni. Am J Epidemiol 1978;24:453 – 69.

[29] Gariepy J, Massonneau M, Levenson J, Heudes D, Simon A. Evidence for in vivo carotid and femoral wall thickening in human hypertension. Hypertension 1993;22:111 – 8.

[30] Gariepy J, Simon A, Massonneau M, Linhart A, Levenson J. Wall thickening of carotid and femoral arteries in male subjects with isolated hypercholesterolemia. Atherosclerosis 1995;113:141 – 51.

[31] Friedewald WT, Levy RI, Fredrickson DS. Estimation of the concentration of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in plasma, without use of the preparative ultracentrifuge. Clin Chem 1972;18:499 – 502.

[32] McGrath BP, Liang YL, Teede H, Shiel LM, Cameron JD, Dart A. Age-related deterioration in arterial structure and function in postmenopausal women. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 1998;18:1149 – 56.

[33] Espeland MA, Applegate W, Furberg CD, Lefkowitz D, Rice L, Hunninghake D. Estrogen replacement therapy and progression of intimal-medial thickness in the carotid arteries of post-menopausal women: ACAPS investigators: asymptomatic carotid atherosclerosis progression study. Am J Epidemiol 1995;142:1011 – 9.

[34] Howard G, Sharrett AR, Heiss G, et al. Carotid artery intimal-medial thickness distribution in general populations as evaluated by B-mode ultrasound: ARIC investigators. Stroke 1993;24:1297 – 304.

[35] Hulley S, Grady D, Bush T, et al. Randomized trial of estrogen plus progestin for secondary prevention of coronary heart dis-ease in postmenopausal women. J Am Med Assoc 1998;280:605 – 13.

[36] Bonithon-Kopp C, Touboul PJ, Berr C, et al. Relation of intima-media thickness to atherosclerotic plaques in carotid ar-teries: the vascular aging (EVA) study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 1996;16:310 – 6.

[37] Chambless LE, Heiss G, Folsom AR. Association of coronary heart disease incidence with carotid arterial wall thickness and major risk factors: the atherosclerosis risk in communities (ARIC) study, 1987 – 1993. Am J Epidemiol 146;1997:483 – 94. [38] Allan PL, Mowbray PI, Lee AJ, Fowkes FG. Relation between

carotid intima-media thickness and symptomatic and asymp-tomatic peripheral arterial disease: the Edinburgh artery study. Stroke 1997;28:348 – 53.

[39] Manolio TA, Furberg C, Shemanski L. Associations of post-menopausal estrogen use with cardiovascular disease and its risk factors in older women. Circulation 1993;88:2163 – 71.

[40] Liang YL, Teede H, Shiel LM, et al. Effects of oestrogen and progesterone on age-related changes in arteries of post-menopausal women. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 1997;24:457 – 9.

thick-ness in women treated with hormone replacement therapy. Ma-turitas 1997;27:47 – 53.

[42] Nabulsi AA, Folsom AR, Szklo M, White A, Higgins M, Heiss

G. No association of menopause and hormone replacement therapy with carotid artery intima-media thickness. Circulation 1996;94:1857 – 63.