www.elsevier.comrlocaterapplanim

Lambs fed protein or energy imbalanced diets

forage in locations and on foods that rectify

imbalances

Lindsey L. Scott

), Frederick D. Provenza

Department of Rangeland Resources, Utah State UniÕersity Logan, UT 84322-5230, USA

Accepted 5 January 2000

Abstract

Ruminants eat a variety of foods from different locations in the environment. While water, cover, social interactions, and predators are all likely to influence choice of foraging location, differences in macronutrient content among forages may also cause ruminants to forage in different locations even during a meal. We hypothesized that lambs forage at locations containing foods that complement their basal diet and meet their nutritional needs. Based on this hypothesis,

Ž .

we predicted that lambs ns12 fed a basal diet low in protein and high in energy would forage

Ž . Ž .

where a high-protein food Food P was located, and that lambs ns12 fed a basal diet low in

Ž .

energy and high in protein would forage where a high-energy food Food E was located. Food P

Ž . Ž . Ž .

was a ground mixture of blood meal 50% , grape pomace 30% , and alfalfa 20% that contained

Ž . Ž .

47% crude protein CP and 2.211 Mcalrkg digestible energy DE . Food E was a ground mixture

Ž . Ž . Ž .

of cornstarch 50% , grape pomace 30% , and rolled barley 20% that contained 6% CP and 3.07

Mcalrkg DE. Food P provided 212 g CPrMcal DE, whereas Food E provided 20 g CPrMcal

DE. Lambs growing at a moderate rate require 179 g CP and 3.95 Mcal DE. During Trial 1, we determined if lambs foraged to correct a nutrient imbalance, and if they preferred a variety of

Ž . Ž .

foods Foods P and E to only one food at a location Food P or E . During Trial 2, we determined if nutrient-imbalanced lambs foraged in the location with the food that corrected the imbalance when the location of the foods changed daily. During Trial 3, lambs were offered familiar foods

ŽFoods P and E at the location furthest — and novel foods wheat and soybean meal at the. Ž .

location nearest — the shelter of their pen. During all three trials, lambs foraged most at the location with the food that contained the highest concentration of the macronutrient lacking in

)Corresponding author.

0168-1591r00r$ - see front matterq2000 Published by Elsevier Science B.V. All rights reserved. Ž .

their basal diet, but they always ate some of both foods. Lambs did not feed exclusively at the

Ž .

location with a variety of foods P and E . Rather, they fed at the location nearest the shelter that contained the macronutrient lacking in their diet. As availability of the food with the needed macronutrient declined in one location, lambs moved to the nearest location that had food with the needed macronutrient. When food that complemented their basal diet was moved to a different location, lambs foraged in the new location. Collectively, these results show that lambs challenged by imbalances in energy or protein selected foods and foraging locations that complemented the

nutrient content of their macronutrient imbalanced basal diets. q2000 Published by Elsevier

Science B.V. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Protein and energy; Macronutrient imbalance; Sheep; Foraging location

1. Introduction

While water, cover, predators, and social interactions all are likely to influence choice of foraging location at one time or another, differences in macronutrient content among forages may also cause ruminants to forage in different locations even during a meal. Range and pasture lands contain a variety of plants with different nutritional profiles and animals must locate plants of different nutritional quality to meet needs. As plants grow,

Ž .

and their sensory flavor and nutritional characteristics change, animals must adapt their choices of foods and foraging locations to avoid eating a nutrient-deficient diet. Our objective was to determine if lambs fed macronutrient imbalanced diets selected foraging locations that met their macronutrient needs.

When given a choice among foods that vary in macronutrients, lambs ingest a diet Ž

with a constant ratio of protein to energy Egan, 1980; Provenza et al., 1996; Wang and

. Ž

Provenza, 1996a,b . In so doing, they maximize growth rate Kyriazakis and Oldham, .

1997 . Lambs maintain macronutrient balance by discriminating between digestive

Ž .

feedback signals from protein and energy Villalba and Provenza, 1999 . The proportion of protein and energy consumed and their rates of degradation in the rumen affect food preference and animal performance by influencing the supply of nitrogen and energy to

Ž

rumen microorganisms and to the host ruminant Sinclair et al., 1993; Villalba and .

Provenza, 1996, 1997a,b,c .

Domestic and wild herbivores eat a variety of plants of different growth stages while foraging on pastures and rangelands. Red deer apparently match nutrient needs to time

Ž .

spent grazing, though there is debate whether protein Langvatn and Hanley, 1993 or

Ž . Ž

energy Wilmshurst and Fryxell, 1995 is more important see also Berteaux et al., .

1998 . The preferences of red deer change seasonally, in part due to changes in plant

Ž .

phenology Wilmshurst et al., 1995 . Perhaps in an effort to find plants that best meet their nutritional needs, while minimizing time spent searching, ruminants eat a variety of

Ž .

foods from different locations even within a meal Provenza, 1996 .

2. Materials and methods

Ž

Twenty-four lambs Finn–Targhee–Columbia–Polypay crossbreeds of both sexes; .

average weight 25 kg were purchased at 6 weeks of age and moved to the Green Canyon Ecology Center in Logan, UT. The same lambs were used in all three trials. At 3 months of age, lambs were blocked by weight and assigned to separate outdoor pens.

Ž . Ž .

Pens 2.4=9.8 m were situated in two adjacent rows 12 pensrrow that shared a Ž

common shelter area. The shelter area was an aluminum canopy 1.8 m wide and 1.7 m .

from the ground supported by metal legs that provided shade for lambs during mid-day heat. Inside each pen were three metal panels, placed on alternating sides of the pen, that extended 3r4 of the width of the pen. The panels created a maze-like environment with three distinct foraging locations approximately 3.3 m apart. Throughout the trials, lambs had access to trace mineral salt with Bovatec and water, located at the furthest end of the pen from the shelter. The basal diet was offered at the opposite end of the pen from the shelter, adjacent to the water, so that lambs became accustomed to feeding at the location most distant from the shelter.

2.1. Pre-treatment

The objective of the pre-treatment was to familiarize lambs with the foods to be used Ž

during the trials. Lambs were offered increasing amounts of Food P high protein, low

. Ž .

energy and Food E high energy, low protein and decreasing amounts of alfalfa pellets

Ž .

and barley, formerly their basal diet, over a 10-day period trial days 1 to 10 .

Table 1

Characteristics of foods used in Trials 1, 2, and 3

Item Basal diets Novel foods

ground alfalfa pellets 20 – – –

1

Ž .

Digestible energy Mcalrkg, as fed basis 2.211 3.07 3.48 3.41

1

Ž .

Digestible protein %, as fed basis 31 2 42 11

1

Ž .

Crude protein %, as fed basis 47 6 45 14

1 Ž .

Each food was ground to 1 mm and mixed. Calculated values for digestible energy DE , digestible

Ž . Ž . Ž .

protein DP , and crude protein CP are based on values as fed basis obtained from the Nutrient

Ž . Ž .

Requirements of Sheep NRC, 1985 : barley 3.26 Mcalrkg DE, 10% DP 12% CP ; alfalfa 2.41 Mcalrkg DE,

Ž . Ž . Ž

12% DP 17 % CP ; cornstarch 4.18 Mcalrkg DE, 0% DP 0% CP . Values for bloodmeal 2.6 Mcalrkg DE,

. Ž .

57% DP, 80% CP and grape pomace 1.09 Mcalrkg DE, 1.6% DP, 12% CP are from the National Academy

Ž .

Food P was a ground mixture of blood meal, grape pomace, and alfalfa that contained

Ž . Ž .

47% crude protein CP and 2.211 Mcalrkg digestible energy DE . Food E was a ground mixture of cornstarch, grape pomace, and rolled barley that contained 6% CP

Ž .

and 3.07 Mcalrkg DE Table 1 . Food P provided 212 g CPrMcal DE, whereas Food E provided 20 g CPrMcal DE. Lambs growing at a moderate rate require 179 g CP and

Ž .

3.95 Mcal DE NRC, 1985 .

On days 11 to 15, lambs were given ad libitum access to Foods P and E to determine

Ž .

the amounts consumed. On average, lambs consumed 40% Food P range 19% to 53%

Ž .

and 60% Food E range 47% to 81% . Lambs were ranked in descending order according to the proportion of Food E consumed and alternatively assigned to two treatments: basal diet of Food P or Food E.

On days 16 and 17, lambs to be fed Food P as their basal diet were offered a mixture of 30% Food E and 70% Food P, whereas lambs to be fed Food E were fed a mixture of

Ž .

90% Food E and 10% Food P 1600 grlambrday . On days 18 and 19, lambs were fed

Ž .

a basal diet of either Food P or Food E 1200 grlambrday , and on day 20, and thereafter, lambs were fed 1100 grlambrday of their respective basal diets. Lambs had access to their basal rations throughout the day and night, except during daily trials.

2.1.1. Protein status

Blood samples were drawn from the jugular vein of each lamb on day 19, just prior

Ž . Ž .

to Trial 1 see below , and serum assayed for blood urea nitrogen BUN . Blood urea

Ž .

nitrogen is an indicator of protein status Hays, 1994 .

2.1.2. Locations

We used a wooden box at each foraging location to hold two plastic food containers. Boxes were located on the side of the panel furthest from the sheltered area of the pen.

Ž .

There were three locations: location nearest the sheltered area near , location midway Ž .

from the shelter to the end of the pen mid , and location furthest from the sheltered area Žfar . Prior to the experiments, familiar foods were placed in the boxes at all three. locations so lambs were accustomed to feeding at the three locations.

Immediately prior to daily trials, lambs were confined to the sheltered area of their individual pen while foods were placed at the three locations. Lambs were then allowed to eat a 15-min meal. Twelve lambs in adjacent pens were fed at 0730 h, whereas the other 12 lambs were fed at 0800 h. The order in which groups of 12 lambs were allowed to eat was alternated daily.

2.2. Trial 1: familiar foods at constant locations

The objective of Trial 1 was to determine whether sheep fed at locations with food that complemented the macronutrient content of their basal diets during a 15-min meal.

Ž .

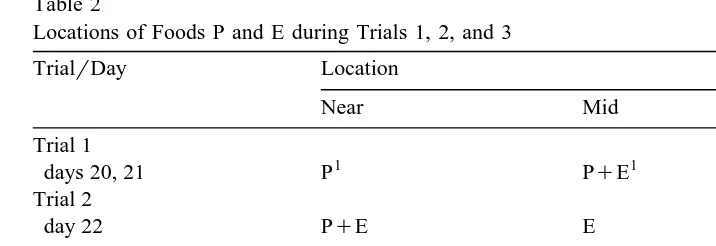

Table 2

Locations of Foods P and E during Trials 1, 2, and 3

TrialrDay Location

P and E refer to foods high in protein and low in energy Food P or high in energy and low in protein

ŽFood E . See Table 1 for food ingredients and chemical characteristics..

2.3. Trial 2: familiar foods at different locations

The objective of Trial 2 was to determine if sheep changed foraging locations when

Ž .

we changed the locations of foods that complemented their basal diet Table 2 . Lambs were offered 100 g of Foods P and E at each location for 15 min on days 22 and 23 to familiarize them with the procedure of changing foods at all three locations. They were offered 225 g of foods P and E at each location for 15 min on days 24 and 25. We measured food intake only on days 24 and 25.

2.4. Trial 3: noÕel and familiar foods at constant locations

The objective of Trial 3 was to determine the response of nutrient-imbalanced lambs

Ž .

to familiar and novel foods. From days 26 to 28, two familiar foods Foods P and E and

Ž . Ž

two novel foods ground wheat and soybean meal were offered 225 grfood, 15 .

minrday at two locations. Familiar foods were placed at the furthest location from the sheltered area and novel foods at the nearest location to determine if novelty or distance from the shelter had a greater influence on the lambs’ foraging behavior; no food was

Ž .

offered at the mid location Table 2 .

2.5. Statistical analyses

Ž . Data for Trials 1 and 2 were analyzed with the MIXED procedure of SAS 1996 .

Ž .

There were two treatments low-protein and low-energy basal diets and lambs were Ž

considered a random factor. The data for Trial 3 intake of Foods E and P and novel

. Ž .

foods offered at two locations were analyzed by MIXED SAS, 1996 as a split-plot.

Ž .

3. Results

3.1. Trial 1: familiar foods at constant locations

In Trial 1, we determined if lambs foraged at locations that contained food that Ž complemented their nutrient imbalance, and if they preferred a variety of foods Foods P

. Ž . Ž .

and E to only one food Food P or E at a location Table 2 .

3.1.1. Protein status

Basal diet affected BUN levels of lambs. Lambs fed a diet low in protein had lower

Ž .

BUN levels than lambs fed a diet low in energy 7 vs. 53 mgrdl; P-0.0001 . The

Ž .

normal range of BUN for sheep is 10 to 26 mgrdl Merck, 1986 .

3.1.2. Familiar foods at constant locations

Lambs fed basal diet P ate more Food E than Food P, whereas lambs fed basal diet E

Ž .

ate more Food P than Food E P-0.05, Table 3 . Lambs fed basal diet P ate more E at

Ž .

location mid — nearest source of Food E — than at location far P-0.05, Table 3 . Lambs fed basal diet E ate more P at locations near and mid — nearest sources of Food

Ž .

P P-0.05, Table 3 . The average intake at the near, mid, and far locations was 43, 52, and 20 g, respectively, for both groups of lambs. Diet, location, and day did not interact ŽP)0.05 ..

3.1.3. Variety location

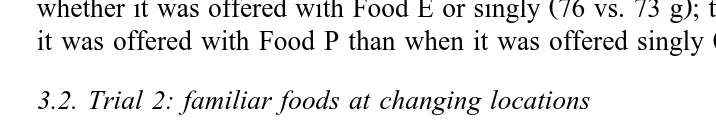

Basal diet affected food choice at the variety location. Lambs fed basal diet P ate more Food E when Foods P and E were offered at one location than at separate locations Ž98 vs. 38 g ; they ate the same amount of Food P whether it was offered with Food E or.

Ž .

singly 14 vs. 14 g . Conversely, lambs fed basal diet E ate similar amounts of Food P

Ž .

whether it was offered with Food E or singly 76 vs. 73 g ; they ate more Food E when

Ž .

it was offered with Food P than when it was offered singly 23 vs. 2 g .

3.2. Trial 2: familiar foods at changing locations

Lambs fed nutrient-imbalanced diets changed foraging location as the locations of the

Ž .

foods changed on days 24 and 25 Table 2 . Lambs maintained on basal diet P fed most

Table 3

Ž . Ž

Intake gr15 min of foods by lambs fed a basal diet that was either low in energy and high in protein Food

. Ž .

P or high in energy and low in protein Food E during Trial 1 1

See Table 1 for composition of Foods P and E. a,b

Ž .

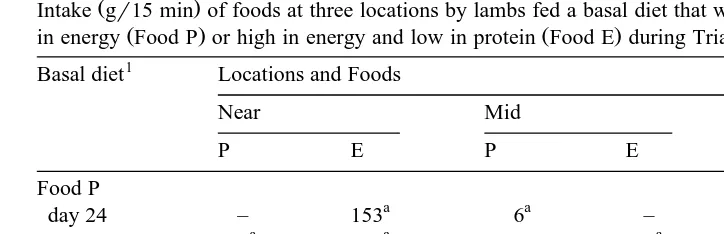

Table 4

Ž .

Intake gr15 min of foods at three locations by lambs fed a basal diet that was either high in protein and low

Ž . Ž .

in energy Food P or high in energy and low in protein Food E during Trial 2 when foods changed location 1

See Table 1 for composition of basal diets and foods .

a,b Ž .

Means in a column having a different superscript differ P-0.05 .

Ž

at the near location — the nearest source of Food E — on days 24 and 25 P-0.05, .

Table 4 . Lambs maintained on basal diet E fed most at the mid location — nearest source of Food P — on day 24, and at near location — nearest source of Food P — on

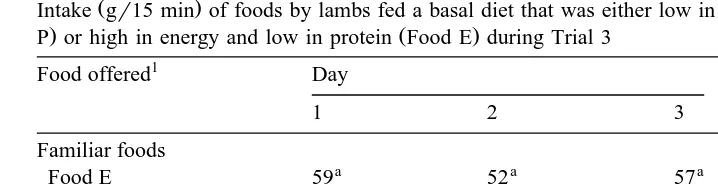

3.3. Trial 3: noÕel foods at constant locations

In Trial 3, lambs fed at the near location with the novel foods in favor of the far location with familiar foods. Lambs in both treatments fed a significant amount at the

Ž .

near location, and they preferred wheat to soybean meal Table 5 . Lambs fed basal diet

Table 5

Ž . Ž

Intake gr15 min of foods by lambs fed a basal diet that was either high in protein and low in energy Food

. Ž .

P or high in energy and low in protein Food E during Trial 3 1Ž .

LocationrFood gr15 min Basal diet SE

Ž . Ž .

Food P high proteinrlow energy Food E high energyrlow protein Near Location

For ingredients and chemical composition of Food P and Food E see Table 1. Calculated values for wheat

Ž . Ž . Ž .

and soybean meal for digestible energy DE , digestible protein DP , and crude protein CP are based on

Ž . Ž .

values as fed basis obtained from the Nutrient Requirements of Sheep NRC, 1985 : wheat — 11% DP, 14% CP, 3.41 Mcalrkg DE; soybean meal — 42% DP, 45% CP, 3.48 Mcalrkg DE.

a,b

Means within row, and c,dmeans within a column and location, having different superscripts differ

Table 6

Ž . Ž

Intake gr15 min of foods by lambs fed a basal diet that was either low in energy and high in protein Food

. Ž .

P or high in energy and low in protein Food E during Trial 3 1

soybean meal 20 21 31 4

1 Ž

See Table 1 for composition of Foods P and E and Table 5 for composition of novel foods wheat and

.

soybean meal .

a,b Ž .

Means with different superscripts differ Ps0.05 .

P ate less Food P and more Food E than lambs fed basal diet E, whereas the reverse was

Ž .

true for lambs fed basal diet E P-0.007; Table 5 . Throughout the 3-day trial, lambs

Ž .

in both groups did not change the amount of Foods P and E eaten P)0.05; Table 6 , but intake of the novel foods — wheat and soybean meal — increased over days ŽP-0.002, Table 6 . Lambs increased the amount of novel foods eaten at the near.

Ž .

location 77 vs. 98 vs. 112 g , and did not change the amount of familiar foods eaten at

Ž . Ž

the far location 105 vs. 94 vs. 98 g from days 26 to 28 LSD0.05s11; location=day .

interaction, P-0.0007 .

4. Discussion

4.1. Familiar foods at constant locations

We hypothesized lambs would forage at locations with foods that complemented the macronutrient content of their basal diet. Lambs fed a basal diet high in energy and low

Ž .

in protein fed at locations with food high in protein Food P , whereas lambs fed a basal Ž diet low in energy and high in protein fed at locations with food high in energy Food

.

E . Thus, our findings are consistent with the notion that food preference depends on

Ž .

nutritional state Villalba and Provenza, 1999 . Nevertheless, even within a 15-min meal lambs did not feed exclusively on Food E or Food P. Rather, they ate relatively more of the food with the macronutrient most limiting in their basal diet.

The ratio of protein to energy in the diet influences preference, even within a meal. Ž .

For example, lambs ruminally infused with protein casein after eating flavored grape pomace subsequently decrease preference for flavored grape pomace paired with casein and increase preference for differently flavored grape pomace previously paired with

Ž .

infusions of energy starch ; conversely, after a meal of barley, preference for flavored Ž .

pomace previously paired with energy starch decreases, while preference for flavored

Ž . Ž .

diets. Lambs fed the high-energy basal diet selected foods with a higher DP:DE ratio

Ž . Ž

than lambs fed the low-energy diet in Trials 1 116 vs. 24 g DPrMcal DE and 2 71 vs. .

24 g DPrMcal DE . When offered novel foods, lambs fed a high-energy basal diet Ž selected foods in a higher protein to energy ratio than lambs fed a low-energy diet 75

. vs. 35 g DPrMcal DE .

Balancing the supply of fermentable carbohydrates and nitrogen within a meal is likely to optimize microbial protein synthesis and maximize the retention of rumen

Ž .

degradable nitrogen Sinclair et al., 1993 . When the rate of ammonia formation exceeds the rate of carbohydrate fermentation, nitrogen is not used efficiently by microbes and a

Ž .

large proportion of nitrogen is excreted as urea Huber and Herrera-Saldana, 1994 . Conversely, lactic acidosis occurs when the rate of carbohydrate fermentation exceeds

Ž .

what can be metabolized in the rumen and liver Yokoyama and Johnson, 1988 . Excesses of nitrogen or energy can cause rapid decreases in food preference in

Ž .

ruminants Provenza, 1995, 1996 .

A food’s flavor and nutrient composition interact to influence food preference ŽProvenza, 1996 . Sensory-specific satiety refers to the decrease in preference for the.

Ž .

flavor of a food as it is consumed Rolls, 1986 , whereas nutrient-specific satiety refers

Ž .

to the decrease in preference for a nutrient consumed in excess Provenza, 1996 . Sensory and nutrient-specific satiety interact to diminish food preference during a meal. Sheep and cattle fed nutritionally balanced food in one of two flavors for as little as 1 day prefer the alternate flavor when offered a choice for 2 hrday for the next 5 days. The decrease in preference becomes more pronounced and persistent when a food is

Ž

either deficient or too high in macronutrients sheep: Early and Provenza, 1998; cattle: .

Atwood et al., 2000 . Lambs prefer a variety of flavored foods when their basal diet and the foods on offer are nutritionally similar, but variety of flavored foods is less important

Ž

when the foods on offer differ nutritionally from their basal diet Scott and Provenza, .

1998 . When flavors and macronutrients vary in foods offered during a meal, lambs

Ž .

prefer foods high in macronutrients regardless of flavor Wang and Provenza, 1997 . Thus, while flavor and nutrients interact to influence preference, flavor is secondary to macronutrients in importance.

4.2. Familiar foods at different locations

As the locations of nutritious foods changed, lambs changed foraging locations. Lambs fed at the location nearest the shelter that contained the macronutrient deficient

Ž in their diet. Intake at the mid location changed as the type of food offered changed i.e.,

.

Food P on day 24 and Food E on day 25 ; lambs fed basal diet E ate more at the mid location on day 24 and lambs fed basal diet P ate more at that location on day 25. Thus, the preference for location was most likely a result of the food offered at the location. Conditioned place preferences can result from the pairing of nutrient feedback at a

Ž .

location with external location cues Carr et al., 1989 . For instance, rats spend more Ž

time at locations where they consume sucrose compared to saccharin White and Carr,

. Ž .

eat more food at less preferred locations when foods they prefer occur at those locations ŽScott and Provenza, 1998 . When a preferred food is moved to a new location marked. by a visual cue, sheep initially return to the original location, and then move to the new

Ž .

location based on the visual cue Edwards et al., 1996 . Cattle quickly learn the locations of nutritious foods, but when the locations change constantly, cattle spend more time

Ž .

searching and less time eating Laca, 1993 .

Lambs fed at a variety of locations, rather than exclusively at the location with a

Ž .

variety of foods i.e., the ‘‘ variety’’ location with both foods . If lambs had preferred the location with the most food, then they should have fed at the variety location. However,

Ž .

they consumed only 12% of the food offered at the variety location 52 of 450 g . Lambs also might be expected to consume all of the food at the first location

Ž .

encountered. However, on average they consumed 26% 43 g of the food offered at the

Ž . Ž .

near location, 62% 105 g of food at the mid location, and 12% 20 g of the food offered at the farthest location. Thus, lambs fed at all three locations and did not consume all of the food at any one location.

Lambs’ fed a high-protein diet were influenced more by the variety of food choices at a location than lambs fed a high-energy diet. Lambs fed a high-protein diet consumed more Food E when it was offered with Food P than when it was offered alone, whereas lambs fed a high-energy diet did not eat more Food P when it was offered with Food E. Rats, too, increase intake of high energy foods when their food choices differ in flavor

Ž .

and texture Naim et al., 1986 .

4.3. NoÕel and familiar foods at constant locations

Animals fed nutrient-deficient diets sample novel foods more readily than animals fed

Ž .

adequate diets Wang and Provenza, 1996a . Thus, we wanted to determine whether lambs readily ingested novel foods high in macronutrients — wheat and soybean meal — even though they had access to familiar foods — P and E — that contained needed macronutrients. All lambs ate significant amounts of the novel foods, relative to the

Ž .

familiar foods, even from day 1 of the trial Table 6 . Lambs increased consumption of both novel foods throughout the trial, but they ate more wheat than soybean meal.

Wheat and soybean meal are both good sources of macronutrients, though soybean meal is much higher than wheat in protein. Thus, we expected lambs fed basal diet P to prefer wheat and lambs fed basal diet E to prefer soybean meal. However, lambs in both groups preferred wheat to soybean meal. Lambs may have generalized a preference from

Ž . Ž .

a familiar grain barley to the novel grain wheat , and in the process showed a greater preference for wheat than soybean meal. All lambs had extensive experience eating barley as part of their basal diet prior to our trials. Grains such as barley and wheat are about 80% starch and lambs generalize preferences from familiar foods high in starch to

Ž .

novel foods high in starch Villalba and Provenza, 2000a . Thus, the macronutrients provided by wheat, along with its relative familiarity, likely contributed to the lambs’ preference for wheat.

Ž . Ž .

have been lower as compared to the novel energy food because sheep did not generalize based on a common flavor. In addition, bloodmeal is less ruminally degradable and has

Ž .

a higher N escape than soybean Loerch et al., 1983 . Soybean meal, on the other hand,

Ž .

is converted more readily than bloodmeal to NH in the rumen Sultan et al., 1992 .3

5. Conclusion

The experiment addressed, with experimental control, the ongoing debate over which has the greater influence on food preference, protein or energy. The results clearly show that lambs challenged by imbalances in energy or protein select foods and foraging locations that complement the nutrient content of their basal diet.

Acknowledgements

This paper is published with approval of the director, Utah Agricultural Experiment Station, Utah State University, Logan, as Journal paper 7137. Research presented herein was supported by grants from Cooperative States Research, Education and Extension Service and the Utah Agricultural Experiment Station.

References

Atwood, S.B., Provenza, F.D., Wiedmeier, R.D., Banner, R.E., 2000. Changes in preferences of gestating heifers fed untreated or ammoniated straw in different flavors. J. Anim. Sci., submitted.

Berteaux, D., Crete, M., Huot, J., Maltais, J., Ouellet, J.-P., 1998. Food choice by white-tailed deer in relation to protein and energy content of the diet: a field experiment. Oecologia 115, 84–92.

Carr, G.D., Fibiger, H.C., Phillips, A.G., 1989. Conditioned place preference as a measure of drug reward. In:

Ž .

Liebaman, J.M., Cooper, S.J. Eds. , The Neuropharmacological Basis of Reward. Clarendon Press, Oxford, England, pp. 264–319.

Early, D., Provenza, F.D., 1998. Food flavor and nutritional characteristics alter dynamics of food preference in lambs. J. Anim. Sci. 76, 728–734.

Edwards, G.R., Newman, J.A., Parsons, A.J., Krebs, J.R., 1996. The use of spatial memory by grazing animals to locate food patches in spatially heterogeneous environments: an example with sheep. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 50, 147–160.

Egan, A., 1980. Host animal-rumen relationships. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 39, 79–87. Hays, S.M., 1994. High ‘‘BUN’’ level a sign of protein waste. Agric. Res. 42, 16–17.

Huber, J.J., Herrera-Saldana, R., 1994. Synchrony of protein and energy supply to enhance fermentation. In:

Ž .

Asplund, J.M. Ed. , Principles of Protein Nutrition of Ruminants. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL, pp. 113–126.

Kyriazakis, I., Oldham, J.D., 1997. Food intake and diet selection of sheep: the effect of manipulating the rates of digestion of carbohydrates and protein of the foods on offer. Br. J. Nutr. 77, 243–254.

Langvatn, R., Hanley, T.A., 1993. Feeding-patch choice by red deer in relation to foraging efficiency. Oecologia 95, 164–170.

Loerch, S.C., Berger, L.L, Plegge, S.D., Fahey, G.C. Jr., 1983. Digestibility and rumen escape of soybean

Ž .

meal blood meal, meat and bone meal and dehydrated alfalfa nitrogen. J. Anim. Sci. 57 4 , 1037–1047.

Ž .

Merck, 1986. In: Fraser, C.M. Ed. , Merck Veterinary Manual. 6th edn. Merck, Rayway, NJ, p. 907. Naim, M., Brand, J.G., Kare, M.R., 1986. Role of variety of food flavor in fat deposition produced by a

Ž .

‘‘cafeteria’’ feeding of nutritionally controlled diets. In: Kare, M.R., Brand, J.G. Eds. , Interaction of the Chemical Senses with Nutrition. Academic Press, Orlando, FL, pp. 269–292.

National Academy of Sciences, 1972. Atlas of Nutritional Data on United States and Canadian Feeds. National Academy of Sciences, Washington, DC.

NRC, 1985. Nutrient Requirements of Sheep. National Academy Press. Washington, DC.

Provenza, F.D., 1995. Postingestive feedback as an elementary determinant of food preference and intake in ruminants. J. Range Manage. 48, 2–17.

Provenza, F.D., 1996. Acquired aversions as the basis for varied diets of ruminants foraging on rangelands. J. Anim. Sci. 74, 2010–2020.

Provenza, F.D., Lynch, J.J., Cheney, C.D., 1995. Effects of a flavor and food restriction on the intake of novel foods by sheep. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 43, 83–93.

Provenza, F.D., Scott, C.B., Phy, T.S., Lynch, J.J., 1996. Preference of sheep for foods varying in flavors and nutrients. J. Anim. Sci. 74, 2355–2361.

Rolls, B.J., 1986. Sensory-specific satiety. Nutr. Rev. 44, 93–101.

SAS, 1996. SASrSTAT Software: Changes and Enhancements through Release 6.12. SAS Institute, Cary, NC.

Scott, C.B., Provenza, F.D., Banner, R.E., 1995. Dietary habits and social interactions affect choice of feeding location by sheep. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 45, 225–237.

Scott, L.L., Provenza, F.D., 1998. Variety of foods and flavors affects selection of foraging locations by sheep. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 61, 113–122.

Sinclair, L.A., Garnsworth, P.C., Newbold, J.R., Buttery, P.J., 1993. Effect of synchronizing the rate of dietary energy and nitrogen release on rumen fermentation and microbial synthesis in sheep. J. Agric. Sci. 120, 251–263.

Sultan, J.I., Firkins, J.L., Weiss, W.P., Loerch, S.C., 1992. Effects of energy level and protein source on nitrogen kinetics in steers fed wheat straw-based diets. J. Anim. Sci. 70, 3916–3921.

Villalba, J.J., Provenza, F.D., 1996. Preference for flavored wheat straw by lambs conditioned with intraruminal administrations of sodium propionate. J. Anim. Sci. 74, 2362–2368.

Villalba, J.J., Provenza, F.D., 1997a. Preference for flavored food by lambs conditioned with intraruminal administrations of nitrogen. Br. J. Nutr. 78, 545–561.

Villalba, J.J., Provenza, F.D., 1997b. Preference for flavored wheat straw by lambs conditioned with intraruminal infusions of acetate and propionate. J. Anim. Sci. 75, 2905–2914.

Villalba, J.J., Provenza, F.D., 1997c. Preference for wheat straw by lambs conditioned with intraruminal infusions of starch. Br. J. Nutr. 77, 287–297.

Villalba, J.J., Provenza, F.D., 1999. Nutrient-specific preferences by lambs conditioned with intraruminal infusions of starch, casein, and water. J. Anim. Sci. 77, 378–387.

Villalba, J.J., Provenza, F.D., 2000. Discriminating among novel foods: effects of energy provision on preferences of lambs for poor-quality foods. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 66, 87–106.

Wang, J., Provenza, F.D., 1996a. Food preference and acceptance of novel foods by lambs depend on the composition of the basal diet. J. Anim. Sci. 74, 2349–2354.

Wang, J., Provenza, F.D., 1996b. Food deprivation affects preference of sheep for foods varying in nutrients and a toxin. J. Chem. Ecol. 22, 2011–2021.

Wang, J., Provenza, F.D., 1997. Dynamics of preference by sheep offered foods varying in flavors, nutrients, and a toxin. J. Chem. Ecol. 23, 275–288.

White, N.M., Carr, G.D., 1985. The conditioned place preference is affected by two independent reinforcement processes. Pharm. Biochem. Behav. 23, 37–42.

Wilmshurst, J.F., Fryxell, J.M., 1995. Patch selection by red deer in relation to energy and protein intake: a

Ž .

Ž

Wilmshurst, J.F., Fryxell, J.M., Hudson, R.J., 1995. Forage quality and patch choice by wapiti CerÕus .

elaphus . Behav. Ecol. 6, 209–217.

Ž .