Transforming

Publishing

O’Reilly Tools of Change delivers a deft mix of the practical and visionary to give the publishing industry the tools and guidance needed to succeed—and the

©2013 O’Reilly Media, Inc. The O’Reilly logo is a registered trademark of O’Reilly Media, Inc. 13124

O’Reilly Media, Inc.

ISBN: 978-1-449-36433-5 Best of TOC, 3rd Edition by O’Reilly Media, Inc.

Copyright © 2013 O’Reilly Media. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America.

Published by O’Reilly Media, Inc., 1005 Gravenstein Highway North, Sebastopol, CA 95472.

O’Reilly books may be purchased for educational, business, or sales promotional use. Online editions are also available for most titles (http://my.safaribooksonline.com). For more information, contact our corporate/institutional sales department: (800) 998-9938 or [email protected].

Cover Designer: Karen Montgomery Interior Designer: David Futato

February 2013: First Edition

Revision History for the First Edition:

2013-2-12 First release

See http://oreilly.com/catalog/errata.csp?isbn=9781449364335 for release details.

Nutshell Handbook, the Nutshell Handbook logo, and the O’Reilly logo are registered trademarks of O’Reilly Media, Inc.

Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their prod‐ ucts are claimed as trademarks. Where those designations appear in this book, and O’Reilly Media, Inc. was aware of a trademark claim, the designations have been printed in caps or initial caps.

Table of Contents

1. Introduction. . . 1

2. Innovation. . . 3

How Agile Methodologies Can Help Publishers 3

What is an agile methodology? 3

How do agile methodologies apply to publishing? 4

Taking a Page Out of ESPN’s Playbook 5

Pay for one, access all 5

Building talent franchises 6

Memorable quotes 6

Perceptive Media: Undoing the Limitations of Traditional Media 7

How does Perceptive Media work, and are there privacy concerns? 7

What driving factors are pointing to the success of this kind of storytelling platform? 8

In the early days, Perceptive Media is being applied to broadcast technology. What potential applications for Perceptive Media do you envision in the publishing industry? 8

Kindle Fire vs iPad: “Good Enough” Will Not Disrupt 9

How disruptive is the Kindle Fire to the low-end tablet market? 9

Is Amazon a threat to Apple? 9

What role do you see Apple playing in the future of publishing — and what current trends do you identify as driving factors? 10

Don’t Build Social — Thoughts on Reinventing the Wheel 10

Services, APIs, and the Complex Web 11

Publishing focus and third-party opportunity 12

Startups and Publishers: It Ain’t Easy 13

If you sell a product publishers don’t want, who is to “blame”? 13

Solutions to solve future problems 13

Where to next? 14

The risk of ceding the future to other players 14

In the end, readers will drive the change 15

It’s Time for a Publishing Incubator 15

Roadblocks 15

People have been thinking about this for awhile 16

The publishing incubator 17

The Slow Pace of eBook Innovation 19

Putting a Value on Classic Content 20

Reading Experience and Mobile Design 22

Mobile design? 22

Five convergence points for mobile design & reading system design 22

Serial Fiction: Everything Old Is New Again 25

Why should you be interested in serial fiction? 25

Frequency, engagement, and experimentation 26

It still comes down to great writing 27

3. Revenue Models. . . 29

Getting the Content Out There Isn’t Enough Anymore 29

In what contexts does content aggregation create the most value? 29

How about paywalls — is anyone doing this properly? What is the best way to make this model work? 30

24Symbols is based on a subscription model. Since your launch, have you had to change the model to make it work? 30

Amazon, eBooks, and Advertising 31

New Life for Used eBooks 33

In-Book Purchases 35

Why a Used eBook Ecosystem Makes Sense 36

4. Rich Content. . . 39

Where do you draw the line between meaningful and

gimmicky interactivity? 39

Are there times when interactivity is detrimental and should be avoided? 40

How have mobile platforms changed the publishing landscape? 41

What kinds of tools do authors need to create interactive content, and what new skills might they need to develop? 41

What are some guidelines authors should follow when considering interactive features for content? 42

How should one decide between building an ebook and building an app? Is there a tipping point? 42

Are eBooks Good Enough Already? 43

5. Data. . . 45

Transforming Data into Narrative Content 45

What does Narrative Science do and how are you applying the technology to journalism? 45

How does data affect the structure of a story? 46

What kinds of stories lend themselves well to this type of system and why? 46

What kinds of stories just won’t work — what are the boundaries or limitations? 46

In what ways can publishers benefit from Narrative Science? 47

In what other industries are you finding applications for Narrative Science? 47

Book Marketing Is Broken. Big Data Can Fix It 47

What are some key findings from the Bookseer beta? 48

What kinds of data are most important for publishers to track? 49

What does real-time data let publishers do? 49

How would you describe the relationship between sales and social media? 50

Will Retailers Start Playing Big Brother with Our Content? 50

6. DRM & Lock-in. . . 53

It’s Time for a Unified eBook Format and the End of DRM 53

Platform lock-in 54

The myth of DRM 54

Lessons from the music industry 55

“Lightweight” DRM Isn’t the Answer 56

Kindle Remorse: Will Consumers Ever Regret eBook Platform Lock-in? 57

Neutralizing Amazon 58

Kindle Serials Is the Next Brick in Amazon’s Walled Garden 59

7. Open. . . 61

Publishing’s “Open” Future 61

Content access via APIs 63

Evolution of DRM 64

Apps, platforms, formats, and HTML5 65

Let’s open this up together 66

Free and the Medium vs. the Message 66

Free as in freedom (and beer) 67

Information and delivery 67

Creating Reader Community with Open APIs 68

Reading is more than a solitary activity 68

The new era of data-driven publishing 69

The consequences of walled gardens 70

Buy Once, Sync Anywhere 71

The problem — a fragmented content ecosystem 71

The proposed solution — an API to share a user’s purchase information 72

What would the access permission API look like? 73

Concept basis of a specification 74

A common data transfer medium 75

The future 76

8. Marketing. . . 79

The Core of the Author Platform Is Unchanged — It’s the Tools that Are Rapidly Changing 79

What is an “author platform” and how is it different today from, say, 10 years ago? 79

What are some of the key ways authors can connect with readers? 80

In marketing your book Cooking for Geeks, what were some of the most successful tactics you used? 80

The Sorry State of eBook Samples, and Four Ways to

Improve Them 82

How Libraries Can Help Publishers with Discovery and Distribution 84

How to De-Risk Book Publishing 85

Selling Ourselves Short on Search and Discovery 88

The 7 Key Features of an Online Community 89

Book Communities 89

The Fundamentals 90

Conclusion 92

9. Direct Sales Channel. . . 93

Direct Sales Uncover Hidden Trends for Publishers 93

Direct Channels and New Tools Bring Freedom and Flexibility 95

Direct Channels 95

Evolving Tools 96

It’s the Brand, Stupid! 97

NY Times eBook Initiative Could Be So Much More 98

10. Legal. . . 99

Fair Use: A Narrow, Subjective, Complicated Safe Haven for Free Speech 99

How is “fair use” defined and what is its legal purpose? 99

Does the breadth of the fair use guidelines cause confusion? 100

What are some best practices people should follow to stay within the guidelines? 100

What are the most common fair use abuses? 101

What kinds of content aren’t protected by copyright or subject to fair use? 101

How would someone know if something is in the public domain or not? 101

What’s your take on Creative Commons licensing? 102

eBook Lending vs Ownership 102

A Screenshot, a Link, and a Heap of Praise Are Met with a Takedown Notice 103

11. Formats. . . 105

Portable Documents for the Open Web (Part 1) 105

What’s up with HTML5 and EPUB 3? (and, is EPUB even

important in an increasingly cloud-centric world?) 105

The Enduring Need for Portable Documents 106

Portable Documents for the Open Web (Part 2) 109

Portable Documents for the Open Web (Part 3) 112

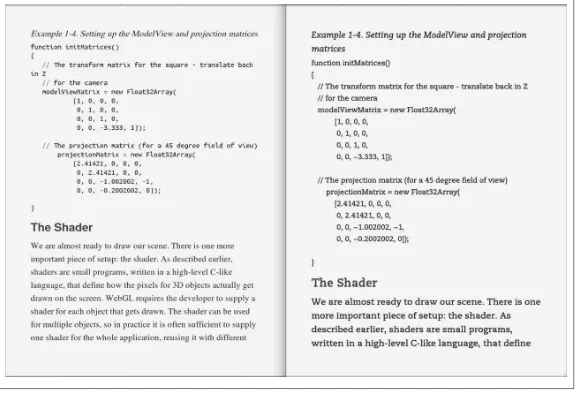

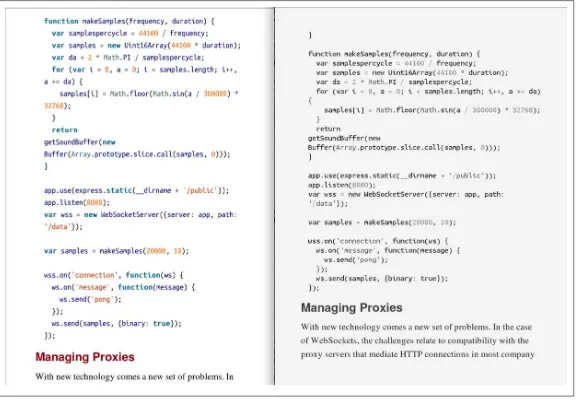

Graceful eBook Degradation 118

IOS 6, Android, HTML5: Which Publishing Platform Prevails? 119

Responsive eBook Content 120

HTML5, EPUB 3, and eBooks vs Web Apps 125

Your mileage may vary, especially on the Nook 125

Distinguishing apps from ebooks 126

eBooks as Native Apps vs Web Apps 127

Distinguishing ebooks from apps 128

Closing the gap between HTML5 and EPUB 3 support 129

Books as Apps Deserve Serious Consideration 130

12. Pricing. . . 133

Piracy, Pricing, and eBook Hoarding 133

Page Count, Pricing, and Value Propositions 134

The Future Is Bright for eBook Prices and Formats 135

Pricing 135

Formats 136

13. Production. . . 137

The New New Typography 137

Browser as typesetting machine 137

The power of CSS and JavaScript 138

Ease and efficiencies 140

BookJS Turns Your Browser into a Print Typesetting Engine 140

Ebook Problem Areas that Need Standardisation 145

Overrides 145

Annotations 148

Modularised EPUB 148

Staying out of CSS 149

Graceful degradation for Fixed Layout 149

What else? 150

InDesign vs CSS 150

Math Typesetting 151

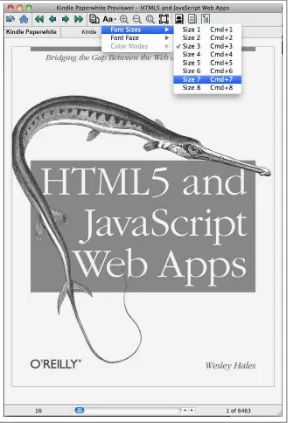

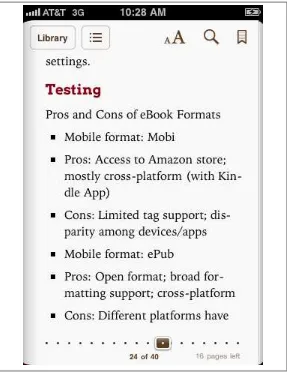

WYSIWYG vs WYSI 154 A Kindle Developer’s 2013 Wishlist 156 1. Add support for embedded audio/video to Kindle Fire 156 2. Add KF8 support for MathML 157 3. Add a Monospace Default Font to Kindle Paperwhite 159 4. Add more granularity to @media query support 160 5. Add a “View Source” option to Kindle Previewer 161

CHAPTER 1

Introduction

2012 was quite a year for change in the publishing industry. Through‐ out the year we used the TOC community site to provide insightful analysis of the latest industry developments. And since ours is a com‐ munity site, the articles we publish aren’t just from the TOC team; we also feature perspectives from many of the top innovators and pub‐ lishing experts.

It wasn’t easy, but we hand-picked the most noteworthy articles from 2012 for inclusion in this Best of TOC collection. We think you’ll agree that the more than 60 pieces featured here represent some of the most thought-provoking dialog from the past year. We’ve arranged the ar‐ ticles by category, so whether you’re most interested in marketing, revenue models, production or innovation in general you’ll find some‐ thing to get your creative juices flowing.

And since we’re all about fostering community at TOC we hope this collection will encourage you to add your voice to the discussion. Since each of these articles is taken from our website you can add your com‐ ments by searching for the headline on toc.oreilly.com.

CHAPTER 2

Innovation

How Agile Methodologies Can Help Publishers

By Jenn Webb

Agile methodologies originated in the software space, but Bookigee

CEO Kristen McLean (@ABCKristen) believes many of the same tech‐ niques can also be applied to content development and publishing workflows. She explains why in the following interview.

What is an agile methodology?

Kristen McLean: An agile methodology is a series of strategies for managing projects and processes that emphasize quick creative cycles, flat self-organizing working groups, the breaking down of complex tasks into smaller achievable goals, and the presumption that you don’t always know what the finished product will be when you begin the process.

These types of methodologies work particularly well in any situation where you are trying to produce a creative product to meet a market that is evolving — like a new piece of software when the core concept needs proof from the user to evolve — or where there needs to be a very direct and engaged relationship between the producers and users of a particular product or service.

Agile methodologies emerged out of the software development com‐ munity in the 1970s, but began to really codify in the 1990s with the rise of several types of “lightweight” methods such as SCRUM, Ex‐ treme Programming, and Adaptive Software Development. These

were all rolled up under the umbrella of agile in 2001, when a group of developers came together to create the Manifesto for Agile Software Development, which set the core principles for this type of working philosophy.

Since then, agile has been applied outside of software development to many different kinds of systems management. Most promote devel‐ opment, teamwork, collaboration, and process adaptability through‐ out the life-cycle of the project. At the end of the day, it’s about getting something out there that we can test and learn from.

How do agile methodologies apply to publishing?

Kristen McLean: In relation to publishing, we’re really talking about two things: agile content development and agile workflow.Agile content development is the idea that we may be able to apply these methodologies to creating content in a very different way than we are traditionally used to. This could mean anything from serialized book content to frequent releases of digital content, like book-related websites, apps, games and more. The discussion of how agile might be applied to traditional book content is just beginning, and I think there’s an open-ended question about how it might intersect with the deeply personal — and not always quick — process of writing a book.

I don’t believe some of our greatest works could have been written in an agile framework (think Hemingway, Roth, or Franzen), but I also believe agile might lend itself to certain kinds of book content, like serial fiction (romance, YA, mystery) and some kinds of non-fiction. The real question has to do with what exactly a “book” is and under‐ standing the leading edge between knowing your audience and crowd‐ sourcing your material.

Publishing houses have been inherently hierarchical because they’ve been organized around a manufacturing process wherein a book’s cre‐ ation has been treated as though it’s on an assembly line. The publisher and editor have typically been the arbiters of content, and as a whole, publishers have not really cultivated a direct relationship with end users. Publishers make. Users buy/read/share, etc.

• Create flat, flexible teams of four to five super-talented individuals with a collective skill set — including editorial, marketing, publi‐ city, production, digital/design, and business — all working to‐ gether from the moment of acquisition (or maybe before). These teams would need to be completely fluent in XHTML and would work under the supervision of a managing publisher whose job would be to create the proper environment and remove impedi‐ ments so the team could do its job.

• An original creative voice and unique point of view will always be important in great writing, but those of us who produce books as trade objects (and package the content in them) have to stop as‐ suming we know what the market wants and start talking to the market as frequently as possible.

• Use forward-facing data and feedback to project future sales. Stop using past sales as the exclusive way to project future sales. The market is moving too fast for that, and we all know there is a di‐ minishing return for the same old, same old.

[This interview was edited and condensed.]

Taking a Page Out of ESPN’s Playbook

By Joe Wikert

If you missed this recent BusinessWeek article about ESPN you owe it to yourself to go back and read it. ESPN is so much more than just a sports network and their brilliant strategy offers plenty of lessons for publishers. Here’s just one important indicator of their success: While the average network earns about 20 cents per subscriber each month ESPN is paid $5.13. That’s more than 25 times the average!

Pay for one, access all

Of course ESPN isn’t just one channel. It’s a family of channels (e.g., ESPN, ESPN2, ESPNU, ESPN Classic, etc.) If you’re a subscriber to any

one of those channels you’re able to watch all of them online via the free WatchESPN app. That means no matter where I am I can catch anything on the ESPN network on my tablet, even those channels I don’t get via cable.

Think about that for a moment. That would be like buying one ebook but getting access to the entire series it’s part of. That’s unheard of in

book publishing. It’s also pretty unusual in network broadcasting but ESPN is ahead of its time. When I stream those channels on Watch‐ ESPN they’re commercial-free; a static logo appears during commer‐ cial breaks. That’s because ESPN hasn’t sold the advertising rights to the streaming broadcasts … yet. They’re willing to stream everything now, even without advertising income, to build a nice solid base to lure those advertisers to the table. Smart.

Building talent franchises

The article talks about Bill Simmons and how the network has turned him into a superstar. So when Simmons had the idea to create Grant‐ land he brought the concept to ESPN to see what they thought. Rather than watching Simmons go off on his own and create something that might compete with them they launched Grantland with him using their ESPN Internet Ventures arm.

When this scenario plays out in the publishing world it usually ends with the author taking the idea somewhere else, often to a self-publisher. It’s clear ESPN is willing to take more risks than the typical book publisher, even if it might lead to cannibalization. As the saying goes though, it’s better to eat your own young than to let someone else do it.

Memorable quotes

This article is loaded with plenty of interesting observations but my favorite quotes are the following:

I have friends who work at Google, and they are beating their chests. ESPN, they never feel like they are at the mountaintop. They’re always thinking they can do something bigger.

He stresses ESPN’s multi-platform advantage: print, radio, broadcast television, cable television, Internet, mobile applications. To date there are no competitors who have assets in all those media. I don’t think you’ll find a lot of hubris here. Or complacency. I don’t think there’s any sense of trying to protect what we’ve got. We’re going to try new things.

Think this advice only applies to the world of television? If so, look at how Rosenfeld Media is reinventing and repositioning itself for the future.

What’s your opinion? Do we need to think more like ESPN? And can you name any publishers who are breaking away from the pack and creating some really innovative, multi-channel products?

Perceptive Media: Undoing the Limitations of

Traditional Media

By Jenn Webb

Recent research indicates a clear desire for interactive engagement in storytelling on the part of audiences. Researchers at the BBC are pio‐ neering the concept of engagement and content personalization with their Perceptive Media experiment. The Next Web’s managing editor Martin Bryant took a look at Perceptive Media and its first incarnation

Breaking Out earlier this summer. He describes the experiment’s con‐

cept:

Essentially, it’s media — either video or audio — that adapts itself based on information it knows about individual viewers. So, if you were watching a game show that you’d never seen before, it might show you an explanation of the rules in detail, while regular views are shown bonus, behind-the-scenes footage instead. … Other smart ideas behind Perceptive Media include the idea that TV hardware could automatically recognize who was watching and tailor the con‐ tent of TV to them automatically.

I reached out to BBC R&D researcher Ian Forrester to find out more about Perceptive Media and the potential for the concept. Our inter‐ view follows.

How does Perceptive Media work, and are there privacy

concerns?

Ian Forrester: Perceptive Media takes storytelling and narrative back to something more aligned to a storyteller and audience around a fire. However, it uses broadcast and Internet technologies in combination to achieve a seamless narrative experience.

Our Breaking Out audio play at futurebroadcasts.com takes advantage of advanced web technologies [to adapt the content], but it’s only one

of many ways we have identified. [Editor’s note: BBC writer Sarah Glenister wrote about her experience working on the Breaking Out audio play experiment here.] The path we took means there are no privacy or data protection issues. Other paths may lean toward learning from what’s being customised (rather then personalised) using a more IP-based solution.

The BBC has a rich history in this field, with the likes of BBC Back‐ stage, which I was the head of for many years. Big data is the trend right now, but in R&D, I’m more interested in implicit data that comes from us and everything we do.

What driving factors are pointing to the success of this

kind of storytelling platform?

Ian Forrester: As an R&D department, its very hard to say for the broadcasting industry, and we have even less experience in the pub‐ lishing industry. However, our research on people’s media habits tells us a lot about people in the lean back and learn forward states. We use that research and what we have seen elsewhere to gauge market ac‐ ceptance.

At the BBC, we don’t look at advertising, but every other company we’ve seen interested in this type technology/experience/media is thinking adverts and product placement.

In the early days, Perceptive Media is being applied to

broadcast technology. What potential applications for

Perceptive Media do you envision in the publishing

industry?

Ian Forrester: We have only scratched the surface and do not know what else it can be adapted toward. In BBC R&D, we watch trends by looking at early innovators. It’s clear as day that ebook reading is taking off finally, and as it moves into the digital domain, why does the con‐ cept of a book have to be static? Skeuomorphism is tragic and feels like a massive step back. But Perceptive Media is undoing the limitations of broadcast. It certainly feels like we can overcome the limitations of publishing, too.

Kindle Fire vs iPad: “Good Enough” Will Not

Disrupt

By Jenn Webb

With its recent release of the new Kindle Fire HD tablets, some have argued that Amazon has declared war on Apple and its iPad. But how serious is the threat? Are the two companies even playing the same game? I reached out to analyst Horace Dediu, founder and author of

Asymco, to get his take. Our short interview follows.

How disruptive is the Kindle Fire to the low-end tablet

market?

Horace Dediu: The problem I see with the Kindle is that the fuel to make it an increasingly better product that can become a general pur‐ pose computer that is hired to do most of what we hire computers to do is not there. I mean, that profitability to invest in new input meth‐ ods, new ways of interacting and new platforms can’t be obtained from a retailer’s margin.

Also, there is a cycle time problem in that the company does not want to orphan its devices since they should “pay themselves off ” as console systems do today. That means the company is not motivated to move its users to newer and “better” solutions that constantly improve. The assumption (implicit) in Kindle is that the product is “good enough” as it is and should be used for many years to come. That’s not a way to ensure improvements necessary to disrupt the computing world.

Lastly, the Amazon brand will have a difficult time reaching six billion consumers. Retail is a notoriously difficult business to expand inter‐ nationally. Digital retail is not much easier than brick-and-mortar. You can see how slow expansion of different media has been for iTunes.

Is Amazon a threat to Apple?

Horace Dediu: Amazon is asymmetric in many ways to Apple. Asym‐ metry can always be a threat because the success of one player is not necessarily to the pain of another. Thus, the “threat” is unfelt, and therefore it’s less likely that there is a response in kind. However, it’s important to couple the asymmetry with a trajectory of improvement

where the threat goes from unfelt to clear and present. That’s where I’m having a hard time putting Amazon on a path that crosses Apple’s fundamental success. I’d say it’s something to watch carefully but not yet something that requires a change in strategy.

I would add one more footnote: Apple TV is a business that matches Kindle perfectly in strategy. Apple TV is a “cheap” piece of hardware that is designed to encourage content consumption. It is something Apple is doing with very modest success but is not abandoning. Apple is exploring this business model.

What role do you see Apple playing in the future of

publishing — and what current trends do you identify

as driving factors?

Horace Dediu: I think Apple will put in a greater effort at the K-12 and higher ed levels. I think the education market resonates strongly with them, and they will develop more product strategy there. The main reason is that there are more decision makers and less concen‐ tration of channel power.

[This interview was lightly edited and condensed.]

Don’t Build Social — Thoughts on

Reinventing the Wheel

By Travis Alber

For the publishing community, social reading has been the hot topic of the year. Since 2008, in fact, social features have spread like wildfire. No publishing conference is complete without a panel discussion on what’s possible. No bundle of Ignite presentations passes muster without a nod to the possibilities created by social features. I under‐ stand why: in-content discussion is exciting, especially as we approach the possibility of real-time interaction.

That’s right. Unless social discussion features are the thing you’re sell‐ ing, don’t build it from scratch. What’s core? Your unique value prop‐ osition. Are you a bookstore or a social network? A school or a social network? A writing community or a social network? A content creator or a social network? The distinction is often lost on a highly-motivated team trying to be all things to all users. For all these examples, the social network is just an aspect of the business. It is an important piece of the experience, but most of the time it’s not worth the incredible investment in time and manpower to build it from scratch.

Services, APIs, and the Complex Web

We’ve seen this happen again and again on the web. If you’ve ever heard of Get Satisfaction or UserVoice, you’re familiar with the evolution of customer service on the web. Ten years ago companies built their own threaded bulletin board systems (and managed the resultant torrent of spam), so that they could “manage the user relationship.” There were some benefits — you could customize the environment completely, for example. But it took the greater portion of a week to build, and a lot of work to maintain. Today that kind of support can be up and running in an hour with third party solutions. Just ask forward thinking com‐ panies like Small Demons and NetGalley, who have embraced these services.

The same can be said of newsletters. For years newsletters were hand-coded (or text-only) and sent from corporate email accounts. Unsub‐ scribing was difficult. Getting email accounts blacklisted (because they looked like spam) was common. Today everyone uses MailChimp,

Constant Contact, Emma, or a similar service. Even if you hire an agency to design and manage a system, they’re likely white-labelling and reselling a service like this to you. Companies no longer build a newsletter service. Now you just use an API to integrate your news‐ letter signup form with a third-party database. Design your newsletter using one of their templates, and let them do all the heavy lifting for email management, bounces, unsubscribes, and usage stats.

There are other examples. Who stores video and builds their own player? Instead we upload it to Vimeo, Brightcove or YouTube, cus‐ tomize the settings, and let the service tell you who watched it, handle storing the heavy files, push player upgrades frequently, etc. Even web

hosting itself has become a service that people sign up for - in many cases setting a project up on AWS (Amazon Web Services, essentially cloud computing) is faster and easier than acquiring a real hardware server and configuring from scratch.

The rise of these third-party solutions are a testament to maturity and complexity of our digital world. Specialization makes systems more stable and dependable. Sure, any time you partner with a service there are risks. But I’ve seen so many publishing projects with social features miss their launch deadline or trash their social features before launch because they found they couldn’t get it built, that it’s hard to watch them spin their wheels over a perceived need for control. That’s a mess of work for something that isn’t the center of your business.

Publishing focus and third-party opportunity

This move to third-party social solutions should start happening with all the education, journalism, authoring platforms, writing commun‐ ities and publishing projects currently in development. Although it sounds simple to just add discussion into content, the devil is in the details. Obviously the front end — the process of adding a comment — takes some work, and the estimation for that is fairly straightfor‐ ward. But what about the paradigm that people use to connect? Are they following people in a Twitter paradigm, or is it a group-based, reciprocal model, like Facebook? Who can delete comments? What can you manage with your administrator dashboard? Are servers ready to scale with peak activity? What kind of stats can you get on how your audience is interacting with your content? Most of these issues don’t relate to the core business.

Startups and Publishers: It Ain’t Easy

By Hugh McGuire

Any startup company trying to work with book publishers will tell you tales of woe and frustration. Big publishers and small publishers (I’ve worked with both) pose different sets of problems for startups, but the end result is a disconnect.

If you sell a product publishers don’t want, who is to

“blame”?

Start-ups tend to blame “slow-moving legacy publishers” … but blame lies as much on startups misunderstanding of publisher needs as on publishers being slow. This is a classic “customer development” prob‐ lem for startups. The reason things don’t work is not that “publishers are too dumb to see how they should change, and choose me to help them,” but rather that the pains publishers are suffering, and solutions startups are offering, are probably not well matched, for a few kinds of reasons:

a) the pain startups are trying to solve is not acute enough for the publishers (yet?)

b) the cost (in time or dollars) to adopt startup solutions is too high (for now?)

c) startups are trying to solve the wrong pain (for today?)

-or-d) startups are addressing their products at the wrong customers

Solutions to solve future problems

In my particular case, I’ve recognized that the PressBooks pitch ends up being something like:

Eventually you’ll need to embrace solutions like PressBooks because solutions like PressBooks will radically transform this market flood‐ ing the publishing market with more books than you ever imagined …

That is … we (and others like us) are trying to solve for publishers problems that we are helping create, and which aren’t quite here yet on a scale that is visible to the day-to-day operations of a publishing com‐ pany. (Certainly these big/catastrophic problems are coming, and soon … but still, it’s a future problem, not a present problem).

Where to next?

So, as a startup, you have to choose what direction to go in:

a) try to solve the pain that traditional publishers have right now, which is felt acutely enough

-or-b) (in our case) try to expand the market by helping millions of new publishers exist … thereby helping create the problems traditional publishers will have to face in the coming years

I like b) as a direction, but in the end it’s not so surprising that existing publishers aren’t falling all over themselves to embrace solutions for problems that aren’t quite here yet.

The risk of ceding the future to other players

Still, there is a case to be made that a publisher with a vision of the future you should be out-front of the changing market. As a fellow-traveller in startup frustration, Andrew Rhomberg at Jellybooks says:

Publishing has been — technically speaking — an amazingly stable industry for a very long time. In defense of publishers: it is going through a transition from analogue to digital AND online faster than any other media industry before it. But by not partnering, publishers are ceding influence over how this industry will be shaped.

And that’s the problem for both startups and publishers … most pub‐ lishing startups are trying to solve problems that will come because of innovations in the future; most publishers are worried about solving the problems of a radically transforming industry right now.

In the end, readers will drive the change

Change is coming though, there is no doubt, and we will know it is here when big numbers of readers start to choose new solutions over existing solutions (see: ebooks). These solutions will come from a mix of startups, of old publishers and new publishers, and crucially, from the big four tech giants: Google, Apple, Amazon, Facebook (and pos‐ sibly others).

In the end, it’s readers who will choose the future, which will follow their eyes, minds and wallets. And for all of us — new players and old — our task now is to present readers with different kinds of futures, and see which ones stick.

It’s Time for a Publishing Incubator

By Travis Alber

Last June, over beer (generally a good place to start), I had a great conversation with entrepreneur Hugh McGuire about how startups are funded in publishing. There was a lot to discuss, a little to celebrate, a bit to complain about, and one fact that we arrived at beyond every‐ thing else. It’s a challenge to raise money for publishing ventures.

Sure, raising funding is always difficult, but publishing presents a par‐ ticular challenge. Publishing is “old media,” and it’s new to the tech‐ nology game (especially in terms of startups focused on the consumer web). There isn’t a real precedent of cooperation between technology and publishing. And that makes it a challenge to find money to build new things.

Roadblocks

Some of the issues come straight out of the investor community:

• Most investors are unfamiliar with publishing. Books seem tradi‐ tional. I can’t tell you how many investors put their personal feel‐ ings into the equation and say things like, “Well, my spouse is in a book club, but I don’t read much so I’m probably not a good fit.” Ouch. Although personal experience figures in somewhat, their total unfamiliarity with the market stops them cold before we’ve even started.

• Concerns about returns on investment. It’s true, we haven’t seen the huge acquisitions like Instagram. Or Yammer. Yet. Publishing is worth billions - it has what everyone wants: content. So maybe the book industry doesn’t seem like a high growth market. One thing is certain, though, as the industry goes digital, those pub‐ lishing billions are going to be spent on something. Clear exits will materialize.

• There’s always the What-If-Google-Does-It argument. To be fair, every startup gets the Google, Amazon, Apple question, which goes something like “What will you do if (all together now), Am‐ azon, Apple, or Google does it?” A few weeks ago I heard Henrik Werdelin of Prehype give a presentation at a TOC event about innovation and he chuckled about this specific question. He poin‐ ted out that at this point Google can pretty much build anything anyone can invent. That shouldn’t be your yardstick. The better question is, are the founders smart enough to offer good strategy, a unique experience, or a new market? If so, Google is much more likely to buy the company once the idea proves out, rather than build every single idea in the world. In short, that question is not a question.

True, there are some people who get investment while working on publishing startups. The list above can be overcome if you’ve worked with those investors before. Or if you’re an Ivy-League ex-Googler that has had a successful exit, you have qualifications that will work in your favor. But that is a frightfully small portion of the people with boots on the ground, developing cool ideas. What about the technically savvy people who don’t meet those criteria (most of the people I know in‐ novating in publishing today)? If they’re starting up in Amercia, those people go out and crash head-first into the arguments listed above, then spend a few years toiling in bootstrapped obscurity.

People have been thinking about this for awhile

is not a “goal” in itself, for example — and that innovation is one of the important pillars of publishing health. He used an example from the gas industry to illustrate how it pooled resources to innovate. He said:

I called the prospect of people not engaging with our content the publishing manifestation of a super-threat. I’d argue (pretty strongly) that it represents a super-threat not just to publishing, but to the way we function as a country, an economy and as a part of a world or‐ der. We have a responsibility to address this threat, not just so that we can make money, but because we’re the ones with the ability to solve it.

Other industries facing an uncertain future have banded together to form and fund superstructures. The Gas Research Institute, for ex‐ ample, was authorized in 1976, at a time when the natural gas industry was highly fragmented among producers, wholesalers and distribu‐ tors. The latter often held a local monopoly.

By 1981, GRI was spending $68.5 million on research and a total of $80.5 million on oversight and R&D. This represented about 0.2% of the wellhead price of gas that year, valued at the time at a bit more than $38 billion.

GRI undertook research and development in four areas…Funding, drawn from a surcharge on sales as well as some government grants, accelerated to something north of $100 million in the mid-1980s. If you look across all of publishing in the United States, it’s about a $40 billion business. Imagine what we could do if we could create and sustain an organization with $80 million a year in funding. It’s also likely that an industry-wide commitment to addressing engagement would garner the external funding that most parties have been un‐ derstandably reluctant to spend on narrower causes.

A good point. A great plan. If CourseSmart and Bookish show us that publishers can partner, then why not partner in innovation? Brian gives a number of concrete suggestions for areas to focus on. I’ve been mulling this over ever since he gave this presentation. Despite his guidelines and recommendations, it hasn’t happened yet. But there’s a way this idea fits neatly into startupland.

The publishing incubator

A similar solution already exists in the tech world: the incubator. If you’re not familiar with it, technology incubators accept applications from startups in small batches. If accepted, the startup gets between

$20,000 - $100,000 (in exchange for around 5% equity), along with three months of office space, mentors, a chance to demo for investors, and a lot of help. Investors get early access to cutting-edge technology. Corporations are encouraged to come in and meet the startups at any point along the way.

Many incubators are industry-specific. For example, there are four healthcare incubators in NYC alone, churning out fresh startups and new technology multiple times a year. Imagine the amount of health‐ care innovation going on right now. Education does this too. Incubator

ImagineK12 is one of many education-focused incubators from across the country — with a group of startups that has raised $10M post-graduation. And Turner Broadcasting just launched an incubator in NYC called Media Camp. Since the products integrate with broadcast media, there is a major focus on mentorship from executives in the field, and a lot of discussion about how to work with big media con‐ glomerates. Sounds a lot like what we need in publishing. Even pub‐ lishing expert Craig Mod recently wrote about how he is struggling with how to distribute his TechFellow money to startups.

Granted, there is some remarkable internal R&D: NYTimes Labs and

The Washington Post Labs are doing good things. Those are com‐ mendable efforts. But those teams are usually small, and since they’re internal they don’t have the massive variation we see in incubators. One company isn’t going to move the needle for an entire industry in that way.

We need an incubator for publishing technology. We need a group of investors and publishers that want to benefit from a pool of innovation, and encourage it grow. With this, publishers would contribute to and sponsor events, perhaps even influence the direction of future part‐ ners. Investors would raise the fund, and choose the most viable start‐ ups. Innovation and disruption might actually find a common ground, as new technologies could drive reading adoption which drive sales (an argument technology writer Paul Carr has made before). We need to bridge publishing and technology, and this gets us there.

The Slow Pace of eBook Innovation

By Joe Wikert

I love this comment from Dave Bricker regarding an earlier post, EPUB 3 facts and forecasts:

Ebook vendors enjoy a closed loop ecosystem. They have millions of reader/customers who are satisfied with EPUB 2 display capabilities and devices. Amazon readers, for example, are largely content with the offerings in the proprietary Kindle store; they’re not lining up with torches and pitchforks to push for improvements. While publishers wait for eReader device manufacturers to add new features and EPUB 3 support, eBooksellers are just as happy to wait.

The best way to promote EPUB 3 right now is to bypass it in favor of delivering ultra-innovative books through the web and app-based distribution. When we can give eReader device makers a compelling reason to bring eReaders into parity with apps and webkit browsers, they’ll put their mouths where our money is. Until eBookstores know they’re losing sales to alternative/open channels, they’re going to sit pretty, stall, and make money doing what they’re doing.

Who’s pushing for innovation in the ebook space? Publishers? No, they’re fairly content with quick-and-dirty p-to-e conversions and they’re risk averse when it comes to making big investments in richer content formats. Retailers? Nope. If retailers were motivated we’d see much broader adoption of EPUB 3 in the various readers and apps out there.

This reminds me of the Android challenge. It’s widely known that new versions of the Android OS don’t get adopted as rapidly as new versions of Apple’s iOS do. That’s because the carriers (e.g., AT&T) and handset makers (e.g., Samsung) have no incentive to update all the existing devices. They’d prefer to force you into a new phone rather than give you a quick OS update with all the new features.

This is one area that Apple really understands and gets right. When they come out with a new version of iOS they have it pushed out to as many customers as possible (assuming their devices can support it). Apple knows there’s so much sex appeal for each new device they don’t have to starve existing device owners from the new OS features.

Will an ebook vendor ever follow Apple’s iOS model and lead the in‐ dustry to a more accelerated pace of innovation? Or is Dave Bricker right that web delivery is the best way forward?

Putting a Value on Classic Content

By Robert Cottrell

Think of a newspaper or magazine as a mountain of data to which a thin new layer of topsoil gets added each day or each week. Everybody sees the new soil. But what’s underneath gets covered up and forgotten. Even the people who own the mountain don’t know much about the lower layers.

That wouldn’t matter if old content was bad content. But it’s not. Jour‐ nalism, at least good journalism, dates much less than we are prone to think.

You never hear anybody say, “I’m not going to listen to that record because it was released last year”, or, “I’m not going to watch that film because it came out last month”. Why are we so much less interested in journalism that’s a month or a year old?

The answer is this: We’ve been on the receiving end of decades of salesmanship from the newspaper industry, telling us that today’s newspaper is essential, but yesterday’s newspaper is worthless.

Look who’s talking. It’s been 50 years since newspapers had the main job of telling people what’s new that day. For decades they’ve been filling their pages with more and more timeless writing. The process is all but complete. Go back into the features pages of your favourite newspaper from a year ago, and you’ll find scarcely a piece that couldn’t appear just as easily today, with a few very minor changes.

All this boils down to a simple proposition: old content is undervalued in the market, relative to new content. There are tens if not hundreds of thousands of articles in writers’ and publishers’ archives which are as good to read today as they were on the day they were published. Yet they are effectively valued by their owners at zero, written off, never to be seen again.

I say all this with feeling because for the past five years I have been curating a recommendations site, The Browser, picking out six to eight of the best pieces published online each day. The thought of all these thousands of pieces, every one a delight, lying dormant in archives, strikes me as deeply unfair to both writers and readers.

so. Why do almost none of them (the New Yorker is an honourable exception) make any serious attempt to organise, prioritise and mon‐ etise their archives? They, after all, are the owners of the mountains, and whatever treasures may lie buried within.

The answer is that they are too fixated on adding the daily or weekly layer of new topsoil. Some of them, I know from experience, see any serious effort to monetise their archive content as a form of competi‐ tion with their new content. At most, they may have some “related content” algorithms, but those algorithms are only going to be as good as the database tagging, which is to say, not good at all.

So here’s my advice: Newspapers and magazines, make your next hire an archive editor. Mine that mountain of fantastic free content. It’s your history and your brand. Don’t just sit on it.

Reading Experience and Mobile Design

By Travis Alber

It’s all about user experience. Once you get past whether a book is available on a particular reading platform, the experience is the dis‐ tinguishing factor. How do you jump back to the table of contents? How do you navigate to the next chapter? How do you leave notes? How does it feel? Is it slick? Clunky? Satisfying? Difficult? Worth the money?

A few weeks ago, at Charleston’s mini-TOC, someone asked me how I approach new digital publishing projects. How to test or design them. Where to start. The easy answer: start by looking at mobile design. The way we design reading experiences and the way we’ve been designing mobile applications are similar. The two are converging.

Mobile design?

Mobile design patterns and best practices overlap with the way we design (or should design) reading experiences. It’s a simple concept that may seem unremarkable — that generic concepts in mobile design and user experience apply when putting together a reading system — but it’s actually at the heart of building something in publishing today.

If this sounds technical, it isn’t. If you’ve used a smartphone to read email, a tablet to read magazines, or an e-reader to consume content, you’re experienced enough to have seen a number of mobile design patterns, even if you didn’t notice them. Consistent functionality, sim‐ ple interfaces, polished graphics, and speedy responses: together these things are all part of mobile experience design. As the opportunity for reading long-form text explodes across different platforms, the reading systems (the way we navigate through the content), will draw from the lessons mobile UX designers have learned over the last decade, from things that had little to do with reading.

Five convergence points for mobile design & reading

system design

1. Simplicity is really, really important

tures. People close apps before bothering with a FAQ. People are im‐ patient. Knowing this, mobile UX designers are specific about what goals they design for, and they stick to those. Most mobile apps do just a few things, and they strive to do them well. That keeps apps very straightforward and simple.

Obviously simplicity has always been a sign of an optimal reading ex‐ perience. Open and read, right? In fact, it’s best if most of the chrome around a book disappears, so readers can focus on the content. It’s natural that the most successful reading systems need to follow this principle of mobile design.

2. Everything takes place in the context of our lives

The first thing UX designers learn when working on a mobile project: people use phones while doing other things. They use them one-handed. They often use them when they are not at home. Design for sub-optimal conditions, because you never know if you have some‐ one’s complete attention.

Reading also takes place within the contextual fabric of how we live our lives. People read books on the subway. At the doctor’s office. In coffee shops. Loud noises, phone calls, check-ins, and conversations all disrupt the experience, even with paper books. As long as we have an easy way to mark our place, a simple way to carry it with us, and a graceful way for features to fail until we can get back to optimal con‐ ditions (for example, in the way a reading service might need to re‐ connect to upload notes), reading systems will act like people expect them to: consistently.

3. No one will wait to read

One the biggest complaints when the original Kindle came out was the page refresh. It was a simple blink to swap out the content from one page to the next. People didn’t want to wait for the next page to load — they expected it to appear instantly.

The same is true of mobile. There are a number of design patterns created to notify the user that content is loading. Different loading bars and contextual messages are designed to manage people’s expectations in a world of high-speed internet, where most clicks bring content to them instantly. This is called latency, and it will drive users away. In both reading systems and mobile apps, latency needs to be under con‐ trol.

4. Patterns matter

Mobile design patterns create a uniform experience across applica‐ tions. For example, if you’re filling out a form in a mobile app, there are some best practices the designer has (hopefully) followed, like sav‐ ing your data as you enter it (people typing with their thumbs don’t have a lot of patience if they have to do it twice), or preserving that data if an error message loads (for the same reason). Granted, these are good guidelines on the web too, but they are really of paramount importance in mobile. These best practices are used inside recom‐ mended patterns, so layouts must have optimal places for error mes‐ sages, or easy ways to update content. You see those patterns repeated in the way lists and forms work across all your mobile apps. (I use patterns and best practices loosely here, the exact definition of each is eternally debated among UX professionals.)

How does this relate to reading systems? On one level, the same applies to users adding notes or reading socially — respect the data because most people won’t enter it twice. But it also has a lot to do with design patterns for reading. The way a table of contents is treated, the way people move through books, the expectation that there will be a way to bookmark a section — these are all patterns.

Last month, at Books in Browsers, Craig Mod gave a presentation on

Subcompact Publishing. In it he talks about how, if you need a screen of instructions on how to use your reading app, it’s probably too com‐ plex. To avoid this, UX designers need to pay attention to user ex‐ pectations and habits. Everything from page-turn options, to title vis‐ ibility to a linkable table of contents, these rules are being created now, and they need to be followed consistently.

5. APIs will be the source of interactivity and real-time action

Mobile systems often pull in different informational feeds: maps, Twit‐ ter posts, ratings. The flow of information into mobile apps means that the applications are richer; these capabilities live on top of an app’s core system.

data. iBooks does this with limited ability now. Enhancements that make reading better without being a direct part of the book are going to very popular. And readers will expect it in the way they expect it from mobile apps.

All of these similarities between mobile design and reading systems exist now; faster, better reading applications will be created if we are mindful of what has already been defined by the mobile experience.

Serial Fiction: Everything Old Is New Again

By Alice Armitage

2012 may be remembered as the year that digital publishing brought serial fiction back to the reading public. Readers in the 19th and early 20th centuries often read fictional stories in installments in newspa‐ pers and magazines: books were simply too expensive for many people. But as affordable paperbacks flooded the market in the mid-1900s, serials lost popularity. Now, however, the ease of delivering install‐ ments to digital devices, combined with the limited time people have to devote to reading, is leading to a resurgence of interest in serial fiction.

Serial fiction has been available on the web since the 1990s. But sud‐ denly in the last six months, there has been an explosion of interest in fiction delivered in installments: Amazon announced its Kindle Serials program, publishing startups introduced their own serial fiction ser‐ ies, (e.g., Byliner, Wattpad, and Plympton), several iOS serial book apps (Silent History and Seven Poets) were launched, and at least one award-winning novelist, Margaret Atwood, began writing her own serial stories.

Why should you be interested in serial fiction?

Whether you are looking at this development as a publisher, reader, or author, there are plenty of reasons.

For a publisher, serial fiction provides ongoing engagement with your readers. Each new installment is delivered to them automatically on their device of choice, bringing your product back into the forefront of their minds. The episodic nature of serial fiction may also increase

the buzz around the author and the story, as there is often a lively online discussion among readers about what may happen in future install‐ ments. This enhances discoverability by creating more opportunities for new readers to hear about the product.

Perhaps most interesting for publishers is the flexibility in payment options for serial fiction. For example, Kindle Serials charges one low price for the purchase of the series up front, with each subsequent installment delivered for free. If the series is well-subscribed, when it is complete, it is offered for sale as a book, either as a paperback or as a Kindle edition. The price for this often exceeds the price for the series if purchased when it began. Other publishers charge a per installment price, usually also offering a discounted price for all installments if paid upfront as the series begins. Some have experimented with of‐ fering the first installment for free, with subsequent installments at a set price, charged as each is delivered. And a few publishers have begun selling subscriptions to their site, with all series then available for free, no matter whether delivered in installments or as a completed whole. Obviously serial fiction lends itself to many different business models.

For a reader, serial fiction provides the opportunity to personally tailor the reading experience. Some serials offer quite short installments, 1,000 words or so per piece (Silent History is an example of this). Oth‐ ers are closer to 10,000 words per installment (like Margaret Atwood’s Wattpad serials), and some are more like short stories in each install‐ ment, running between 50,000 and 100,000 words (like Margaret At‐ wood’s “Positron” serial on Byliner).

Frequency, engagement, and experimentation

have changed the ending or the level of involvement of secondary characters based on reader feedback.) And lastly, the need for cliff‐ hangers at the end of each installment, as well as other techniques for bringing readers back to the story after a waiting period, means that serial fiction is often more intricately plotted and engaging than a stand alone book might be.

For an author, serial fiction offers the chance to experiment with new ways of storytelling. Pieces are shorter and more quickly delivered to readers. This allows authors the possibility of receiving reader feed‐ back before the story is finished — a kind of agile development model for writing. And for serial fiction offered as apps on Apple devices, there is the opportunity to use the increased functionality of the mobile device as a part of the storytelling. For example, Silent History tells the main story through short “Testimonials”, written by the authors. But there is the option of reading and/or creating what are called “Field Reports.” These stories (based on the fictional premise of the app) are written by the community of readers and can be accessed only within 10 meters of the GPS location about which the field report is written. Another app, Seven Poets, offers not just the story installments, but also “newspaper articles” on the main events in the story, as well as challenges to the reader based on the events of each installment, the results of which are stored and can be shared as “Your Story” with a reader’s own community.

It still comes down to great writing

Overall, after reading many different kinds and examples of the serial fiction that has recently burst onto the scene, I have to say I like the flexibility of matching my current reading needs (the length of time I have, my attention span at the moment, the situation I’m reading in — is it a quiet doctor’s office or the DMV?) with all the different sorts of serials available at an affordable price. And I am amused by the new ways of telling stories utilizing the bells and whistles of my mobile devices. But I have discovered that the measuring stick for serials is the same as the one I use for all books: How good is the writing? Over time, neither the novelty of periodic delivery of installments nor the new storytelling techniques available through my device kept me in‐ terested in the story unless the plot was intriguing, the characters were fully developed, and the writing was engaging. Bottom line: I like the flexibility of serial fiction, but only good writing will keep me coming back for more.

CHAPTER 3

Revenue Models

Getting the Content Out There Isn’t Enough

Anymore

By Jenn Webb

Content is still king, but now it has to share its crown. Justo Hidalgo (@justohidalgo), co-founder of 24symbols, believes added value and personalized services are just as important as the content itself. He explains why in the following interview.

In what contexts does content aggregation create the

most value?

Justo Hidalgo: Companies that take content and contribute added value for readers are generally better positioned to succeed. Specifi‐ cally, I believe content aggregation is useful in the following contexts:

• Hubs — Why did The Huffington Post gain so much success? Why is Spotify increasing its number of users constantly? And why is Netflix in trouble? There are of course many reasons, but one is particularly clear: Users want hubs where they can find most, if not all, of the content they want. Content aggregation enables just that. While creating silos of information can be valuable in specific niche markets, it does not work in mass markets unless your brand recognition is immensely high.

• Value addition — Social recommendation is a typical yet good example of value addition to content, as is adding information

about a title’s author and surrounding context. This meta-information can be manually or automatically added. I believe in the power of machine learning and data mining technologies ap‐ plied to this area, along with human expertise.

• Discovery — While having thousands or millions of books com‐ plicates a search, it also creates an impressive opportunity: There are more relevant datasets to match recommendations and tastes as well as to facilitate serendipitous discovery.

How about paywalls — is anyone doing this properly?

What is the best way to make this model work?

Justo Hidalgo: Paywall models only work if what you offer is extremely exclusive. Maybe the New York Times or the Financial Times can suc‐ ceed at offering paywall content, but in a digital world absolutely nothing can be prevented from being copied and propagated. So the key is not the content itself, but the value-added service offered on top of it. Only a mixture of high-quality content and a great service will be compelling enough to make users pay.

In general, the content — and the service that contains it — needs to be testable, and models like freemium, whether “free” is forever or for a limited time, are critical in the digital content world. Spotify is cre‐ ating a massive user base with this model, even now that its free of‐ fering is not as compelling as before. The New York Times is also using a freemium approach, letting its users read a few articles per month for free before the paywall kicks in.

The challenge of paywalls in this context is that high quality is not only expected, but required. With so many good free sources of information available, if I am to pay for it, I expect it to be impressive — not only in terms of pure content, but also in terms of the benefits the service provides in a personalized way.

24Symbols is based on a subscription model. Since your

launch, have you had to change the model to make it

work?

In terms of the model, the basics are the same. We believe a cloud-based social reader with a freemium subscription model is key for the future of publishing. And we recently branched out to license our technology to companies and institutions that want to offer a cloud reader to their customers or employees. This was in our minds from the start, but we wanted to focus on the consumer offering first and create a top-class platform.

[This interview was edited and condensed.]

Amazon, eBooks, and Advertising

By Joe Wikert

It all started harmlessly enough with Amazon’s Kindle with Special Offers. That’s the cheaper Kindle that displays ads when the device is in sleep mode or at the bottom of the screen when paging through the owner’s catalog of books. It is very unobtrusive and, since it lowered the price of the device, has made that Kindle an extremely popular device.

Now there are rumors that Amazon is selling ad space on the Kindle Fire’s welcome screen. That sounds pretty reasonable, too, as it’s a sim‐ ple way for Amazon to drive a bit of additional income that’s pure profit for them.

Given that Amazon’s goal is to offer customers the lowest prices on everything, what’s the next logical step? How about even lower prices on ebooks where Amazon starts making money on in-book ads? Think Google AdWords, built right into the book. Of course, Amazon won’t want to use Google’s platform. They’ll use their own so they keep 100% of the revenue.

The changes the DOJ is requiring for the agency model means a retailer can’t sell ebooks at a loss, but they can still sell them for no profit, or break even. In other words, the 30% the retailer would keep on an agency ebook sale can be passed along to the customer as a 30% dis‐ count on the list price, but that’s as deep a discount as that retailer can offer.

The rules are different with the wholesale model. Amazon already loses money on sales of many wholesale-model ebooks. Let’s talk about a hypothetical wholesale model title with a digital list price of $25. Am‐ azon is required to pay the publisher roughly half that price, or about

$12.50 for every copy sold, but that ebook might be one of the many that are listed at $9.99 for the Kindle. So every time Amazon sells a copy, they lose $2.51 ($12.50 minus $9.99). Amazon has deep enough pockets to continue doing this, though, so they’re quite comfortable losing money and building market share.

So, what’s preventing Amazon from taking an even bigger loss and selling that ebook for $4.99 or $0.99 instead? In the wholesale model world, the answer to that question is: “nothing is preventing them from doing that.” And if selling ebooks at a loss for $9.99 makes sense, es‐ pecially when it comes to building market share, why doesn’t it also make sense to sell them at $4.99, $0.99 or even free for some period of time? It probably depends on how much pain Amazon wants to inflict on other retailers and how much attention they’re willing to call to themselves for predatory pricing.

Make no mistake about the fact that Amazon would love to see ebook pricing approach zero. That’s right. Zero. That might seem outlandish, but isn’t that exactly what they’re doing with their Kindle Owner’s Lending Library program? Now you can read ebooks for free as part of your Prime membership. The cost of Prime didn’t go up, so they’ve essentially made the consumer price of those ebooks zero.

Why wouldn’t they take the same approach with in-book advertising?

At some point in the not-too-distant future, I believe we’ll see ebooks on Amazon at fire-sale prices. I’m not just talking about self-published titles or books nobody wants. I’ll bet this happens with some bestsellers and midlist titles. Amazon will make a big deal out of it and note how these cheaper prices are only available through Amazon’s in-book ad‐ vertising program. Maybe they’ll still offer the ad-free editions at the higher prices, but you can bet they’ll make the ad-subsidized editions irresistible.

Remember that they can only do this for books in the wholesale model. But quite a few publishers use the wholesale model, so the list oppor‐ tunities are enormous. And as Amazon builds momentum with this, they’ll also build a very strong advertising platform. One that could conceivably compete with Google AdWords outside of ebooks, too.

Imagine B&N trying to compete if a large portion of Amazon’s ebook list drops from $9.99 to $4.99 or less. Even with Microsoft’s cash in‐ jection, B&N simply doesn’t have deep enough pockets to compete on losses like this, at least not for very long.

At the same time, Amazon will likely tell publishers the only way they can compete is by significantly lowering their ebook list prices. They’ll have the data to show how sales went up dramatically when consumer prices dropped to $4.99 or less. I wouldn’t be surprised if Amazon would give preferential treatment to publishers who agree to lower their list prices (e.g., more promotions, better visibility, etc.).

By the time all that happens, Amazon will probably have more than 90% of the ebook market and a nice chunk of their ebook list that no longer has to be sold at a loss. And oh, let’s not forget about the won‐ derful in-book advertising platform they’ll have built buy then. That’s an advertising revenue stream that Amazon would not have to share with publishers or authors. That might be the most important point of all.

What do you think? Why wouldn’t Amazon follow this strategy, espe‐ cially since it helps eliminate competitors, leads to market dominance and fixes the loss-leader problem they currently have with many ebook sales?

[This post originally appeared on Joe Wikert’s Publishing 2020 Blog (Why

Advertising Could Become Amazon’s Knockout Punch). This version has

been lightly edited.]

New Life for Used eBooks

By Joe Wikert

I’ve got quite a few ebooks in two different accounts that I’ve read and will never read again. I’ll bet you do, too. In the print world, we’d pass those along to friends, resell them or donate them to the local library. Good luck doing any of those things with an ebook.

Once you buy an ebook, you’re pretty much stuck with it. That’s yet another reason why consumers want low ebook prices. Ebooks are lacking some of the basic features of a print book, so of course they

![Figure 13-5. Three books produced by the BookJS in-browser typeset‐ting library [photo by Kristin Tretheway]](https://thumb-ap.123doks.com/thumbv2/123dok/3939366.1882786/157.432.73.360.52.355/figure-produced-bookjs-browser-typeset-library-kristin-tretheway.webp)