Best of TOC, 3rd Edition

2. Innovation

How Agile Methodologies Can Help Publishers What is an agile methodology?

How do agile methodologies apply to publishing? Taking a Page Out of ESPN’s Playbook

Pay for one, access all Building talent franchises Memorable quotes

Perceptive Media: Undoing the Limitations of Traditional Media How does Perceptive Media work, and are there privacy concerns? What driving factors are pointing to the success of this kind of storytelling platform?

In the early days, Perceptive Media is being applied to broadcast technology. What potential applications for Perceptive Media do you envision in the publishing industry?

Kindle Fire vs iPad: “Good Enough” Will Not Disrupt

How disruptive is the Kindle Fire to the low-end tablet market? Is Amazon a threat to Apple?

What role do you see Apple playing in the future of publishing — and what current trends do you identify as driving factors?

Don’t Build Social — Thoughts on Reinventing the Wheel Services, APIs, and the Complex Web

Publishing focus and third-party opportunity Startups and Publishers: It Ain’t Easy

If you sell a product publishers don’t want, who is to “blame”? Solutions to solve future problems

Where to next?

The risk of ceding the future to other players In the end, readers will drive the change It’s Time for a Publishing Incubator

Roadblocks

People have been thinking about this for awhile The publishing incubator

Putting a Value on Classic Content Reading Experience and Mobile Design

Mobile design?

Five convergence points for mobile design & reading system design Serial Fiction: Everything Old Is New Again

3. Revenue Models

Getting the Content Out There Isn’t Enough Anymore

In what contexts does content aggregation create the most value?

How about paywalls — is anyone doing this properly? What is the best way to make this model work?

24Symbols is based on a subscription model. Since your launch, have you had to change the model to make it work?

Amazon, eBooks, and Advertising New Life for Used eBooks

In-Book Purchases

4. Rich Content

In the Case of Interactivity, We’re Still at the Phase of Irrational Enthusiasm

Where do you draw the line between meaningful and gimmicky interactivity?

Are there times when interactivity is detrimental and should be avoided? How have mobile platforms changed the publishing landscape?

What kinds of tools do authors need to create interactive content, and what new skills might they need to develop?

What are some guidelines authors should follow when considering interactive features for content?

How should one decide between building an ebook and building an app? Is there a tipping point?

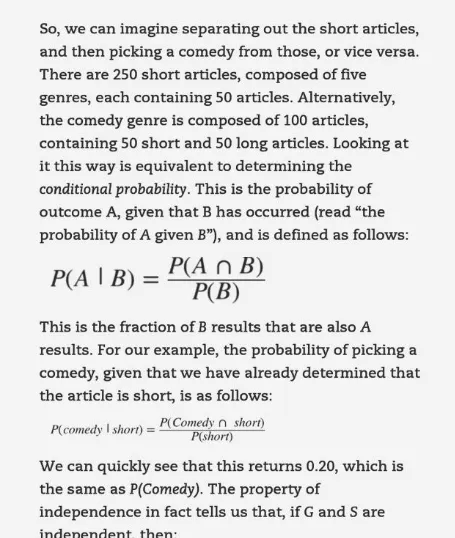

5. Data

Transforming Data into Narrative Content

What does Narrative Science do and how are you applying the technology to journalism?

How does data affect the structure of a story?

What kinds of stories lend themselves well to this type of system and why?

What kinds of stories just won’t work — what are the boundaries or limitations?

In what ways can publishers benefit from Narrative Science? In what other industries are you finding applications for Narrative Science?

Book Marketing Is Broken. Big Data Can Fix It

What are some key findings from the Bookseer beta?

What kinds of data are most important for publishers to track? What does real-time data let publishers do?

6. DRM & Lock-in

It’s Time for a Unified eBook Format and the End of DRM Platform lock-in

The myth of DRM

Lessons from the music industry “Lightweight” DRM Isn’t the Answer

Kindle Remorse: Will Consumers Ever Regret eBook Platform Lock-in? Neutralizing Amazon

7. Open

Publishing’s “Open” Future Content access via APIs Evolution of DRM

Apps, platforms, formats, and HTML5 Let’s open this up together

Free and the Medium vs. the Message Free as in freedom (and beer)

Information and delivery

Creating Reader Community with Open APIs Reading is more than a solitary activity The new era of data-driven publishing The consequences of walled gardens Buy Once, Sync Anywhere

The problem — a fragmented content ecosystem

The proposed solution — an API to share a user’s purchase information What would the access permission API look like?

8. Marketing

The Core of the Author Platform Is Unchanged — It’s the Tools that Are Rapidly Changing

What is an “author platform” and how is it different today from, say, 10 years ago?

What are some of the key ways authors can connect with readers?

In marketing your book Cooking for Geeks, what were some of the most successful tactics you used?

What advice would you offer to new authors just starting out?

The Sorry State of eBook Samples, and Four Ways to Improve Them How Libraries Can Help Publishers with Discovery and Distribution How to De-Risk Book Publishing

Selling Ourselves Short on Search and Discovery The 7 Key Features of an Online Community

9. Direct Sales Channel

Direct Sales Uncover Hidden Trends for Publishers

Direct Channels and New Tools Bring Freedom and Flexibility Direct Channels

Evolving Tools

It’s the Brand, Stupid!

10. Legal

Fair Use: A Narrow, Subjective, Complicated Safe Haven for Free Speech How is “fair use” defined and what is its legal purpose?

Does the breadth of the fair use guidelines cause confusion?

What are some best practices people should follow to stay within the guidelines?

What are the most common fair use abuses?

What kinds of content aren’t protected by copyright or subject to fair use? How would someone know if something is in the public domain or not? What’s your take on Creative Commons licensing?

eBook Lending vs Ownership

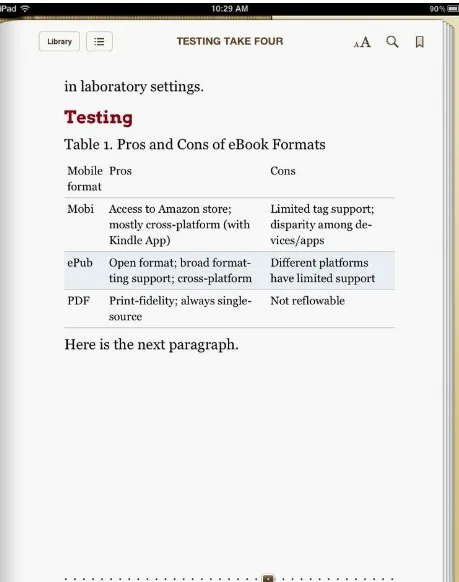

11. Formats

Portable Documents for the Open Web (Part 1)

What’s up with HTML5 and EPUB 3? (and, is EPUB even important in an increasingly cloud-centric world?)

The Enduring Need for Portable Documents Portable Documents for the Open Web (Part 2) Portable Documents for the Open Web (Part 3) Graceful eBook Degradation

IOS 6, Android, HTML5: Which Publishing Platform Prevails? Responsive eBook Content

HTML5, EPUB 3, and eBooks vs Web Apps Your mileage may vary, especially on the Nook Distinguishing apps from ebooks

eBooks as Native Apps vs Web Apps Distinguishing ebooks from apps

12. Pricing

Piracy, Pricing, and eBook Hoarding

Page Count, Pricing, and Value Propositions

The Future Is Bright for eBook Prices and Formats Pricing

13. Production

The New New Typography

Browser as typesetting machine The power of CSS and JavaScript Ease and efficiencies

BookJS Turns Your Browser into a Print Typesetting Engine Ebook Problem Areas that Need Standardisation

Overrides

So why is this really interesting to publishing? WYSIWYG vs WYSI

A Kindle Developer’s 2013 Wishlist

1. Add support for embedded audio/video to Kindle Fire 2. Add KF8 support for MathML

3. Add a Monospace Default Font to Kindle Paperwhite 4. Add more granularity to @media query support

Best of TOC, 3rd Edition

O’Reilly TOC Team

Special Upgrade Offer

If you purchased this ebook directly from oreilly.com, you have the following benefits:

DRM-free ebooks — use your ebooks across devices without restrictions or limitations

Multiple formats — use on your laptop, tablet, or phone Lifetime access, with free updates

Dropbox syncing — your files, anywhere

If you purchased this ebook from another retailer, you can upgrade your ebook to take advantage of all these benefits for just $4.99. Click here to access your ebook upgrade.

Chapter 1. Introduction

2012 was quite a year for change in the publishing industry. Throughout the year we used the TOC community site to provide insightful analysis of the latest industry developments. And since ours is a community site, the articles we publish aren’t just from the TOC team; we also feature perspectives from many of the top innovators and publishing experts.

It wasn’t easy, but we hand-picked the most noteworthy articles from 2012 for inclusion in this Best of TOC collection. We think you’ll agree that the more than 60 pieces featured here represent some of the most

thought-provoking dialog from the past year. We’ve arranged the articles by category, so whether you’re most interested in marketing, revenue models, production or innovation in general you’ll find something to get your creative juices flowing.

And since we’re all about fostering community at TOC we hope this

How Agile Methodologies Can Help Publishers

By Jenn WebbWhat is an agile methodology?

Kristen McLean: An agile methodology is a series of strategies for

managing projects and processes that emphasize quick creative cycles, flat self-organizing working groups, the breaking down of complex tasks into smaller achievable goals, and the presumption that you don’t always know what the finished product will be when you begin the process.

These types of methodologies work particularly well in any situation where you are trying to produce a creative product to meet a market that is evolving — like a new piece of software when the core concept needs proof from the user to evolve — or where there needs to be a very direct and engaged relationship between the producers and users of a particular product or service.

Agile methodologies emerged out of the software development community in the 1970s, but began to really codify in the 1990s with the rise of several types of “lightweight” methods such as SCRUM, Extreme Programming, and

Adaptive Software Development. These were all rolled up under the umbrella of agile in 2001, when a group of developers came together to create the

Manifesto for Agile Software Development, which set the core principles for this type of working philosophy.

Since then, agile has been applied outside of software development to many different kinds of systems management. Most promote development,

How do agile methodologies apply to

publishing?

Kristen McLean: In relation to publishing, we’re really talking about two things: agile content development and agile workflow.

Agile content development is the idea that we may be able to apply these methodologies to creating content in a very different way than we are

traditionally used to. This could mean anything from serialized book content to frequent releases of digital content, like book-related websites, apps, games and more. The discussion of how agile might be applied to traditional book content is just beginning, and I think there’s an open-ended question about how it might intersect with the deeply personal — and not always quick — process of writing a book.

I don’t believe some of our greatest works could have been written in an agile framework (think Hemingway, Roth, or Franzen), but I also believe agile might lend itself to certain kinds of book content, like serial fiction (romance, YA, mystery) and some kinds of non-fiction. The real question has to do with

what exactly a “book” is and understanding the leading edge between knowing your audience and crowdsourcing your material.

Publishing houses have been inherently hierarchical because they’ve been organized around a manufacturing process wherein a book’s creation has been treated as though it’s on an assembly line. The publisher and editor have typically been the arbiters of content, and as a whole, publishers have not really cultivated a direct relationship with end users. Publishers make. Users buy/read/share, etc.

Publishers need to adapt to a radically different way of working. For

example, here’s a few ways agile strategies could help with the adaptation of a publishing workflow:

remove impediments so the team could do its job.

An original creative voice and unique point of view will always be important in great writing, but those of us who produce books as trade objects (and package the content in them) have to stop assuming we know what the market wants and start talking to the market as frequently as possible.

Use forward-facing data and feedback to project future sales. Stop using past sales as the exclusive way to project future sales. The market is

moving too fast for that, and we all know there is a diminishing return for the same old, same old.

Taking a Page Out of ESPN’s Playbook

By Joe WikertIf you missed this recent BusinessWeek article about ESPN you owe it to yourself to go back and read it. ESPN is so much more than just a sports network and their brilliant strategy offers plenty of lessons for publishers. Here’s just one important indicator of their success: While the average

Pay for one, access all

Of course ESPN isn’t just one channel. It’s a family of channels (e.g., ESPN, ESPN2, ESPNU, ESPN Classic, etc.) If you’re a subscriber to any one of those channels you’re able to watch all of them online via the free

Building talent franchises

The article talks about Bill Simmons and how the network has turned him into a superstar. So when Simmons had the idea to create Grantland he

brought the concept to ESPN to see what they thought. Rather than watching Simmons go off on his own and create something that might compete with them they launched Grantland with him using their ESPN Internet Ventures

arm.

Memorable quotes

This article is loaded with plenty of interesting observations but my favorite quotes are the following:

I have friends who work at Google, and they are beating their chests. ESPN, they never feel like they are at the mountaintop. They’re always thinking they can do something bigger.

He stresses ESPN’s multi-platform advantage: print, radio, broadcast television, cable television, Internet, mobile applications. To date there are no competitors who have assets in all those media. I don’t think you’ll find a lot of hubris here. Or complacency. I don’t think there’s any sense of trying to protect what we’ve got. We’re going to try new things.

Meanwhile, most book publishers today seem content with high growth rates (off small bases) for what’s nothing more than quick-and-dirty print-to-e conversions. There’s certainly not much happening in the multi-format, multi-channel world ESPN is pioneering.

Perceptive Media: Undoing the Limitations of

Traditional Media

By Jenn Webb

Recent research indicates a clear desire for interactive engagement in

storytelling on the part of audiences. Researchers at the BBC are pioneering the concept of engagement and content personalization with their Perceptive Media experiment. The Next Web’s managing editor Martin Bryant took a look at Perceptive Media and its first incarnation Breaking Out earlier this summer. He describes the experiment’s concept:

Essentially, it’s media — either video or audio — that adapts itself based on information it knows about individual viewers. So, if you were watching a game show that you’d never seen before, it might show you an explanation of the rules in detail, while regular views are shown bonus, behind-the-scenes footage instead. … Other smart ideas behind Perceptive Media include the idea that TV hardware could automatically recognize who was watching and tailor the content of TV to them automatically.

How does Perceptive Media work, and are

there privacy concerns?

Ian Forrester: Perceptive Media takes storytelling and narrative back to something more aligned to a storyteller and audience around a fire. However, it uses broadcast and Internet technologies in combination to achieve a

seamless narrative experience.

Our Breaking Out audio play at futurebroadcasts.com takes advantage of advanced web technologies [to adapt the content], but it’s only one of many ways we have identified. [Editor’s note: BBC writer Sarah Glenister wrote about her experience working on the Breaking Out audio play experiment

here.] The path we took means there are no privacy or data protection issues. Other paths may lean toward learning from what’s being customised (rather then personalised) using a more IP-based solution.

The BBC has a rich history in this field, with the likes of BBC Backstage, which I was the head of for many years. Big data is the trend right now, but in R&D, I’m more interested in implicit data that comes from us and

What driving factors are pointing to the

success of this kind of storytelling platform?

Ian Forrester: As an R&D department, its very hard to say for the

broadcasting industry, and we have even less experience in the publishing industry. However, our research on people’s media habits tells us a lot about people in the lean back and learn forward states. We use that research and what we have seen elsewhere to gauge market acceptance.

In the early days, Perceptive Media is being

applied to broadcast technology. What

potential applications for Perceptive Media do

you envision in the publishing industry?

Ian Forrester: We have only scratched the surface and do not know what else it can be adapted toward. In BBC R&D, we watch trends by looking at early innovators. It’s clear as day that ebook reading is taking off finally, and as it moves into the digital domain, why does the concept of a book have to be static? Skeuomorphism is tragic and feels like a massive step back. But Perceptive Media is undoing the limitations of broadcast. It certainly feels like we can overcome the limitations of publishing, too.

Kindle Fire vs iPad: “Good Enough” Will Not

Disrupt

By Jenn Webb

With its recent release of the new Kindle Fire HD tablets, some have argued

How disruptive is the Kindle Fire to the

low-end tablet market?

Horace Dediu: The problem I see with the Kindle is that the fuel to make it an increasingly better product that can become a general purpose computer that is hired to do most of what we hire computers to do is not there. I mean, that profitability to invest in new input methods, new ways of interacting and new platforms can’t be obtained from a retailer’s margin.

Also, there is a cycle time problem in that the company does not want to orphan its devices since they should “pay themselves off” as console systems do today. That means the company is not motivated to move its users to newer and “better” solutions that constantly improve. The assumption

(implicit) in Kindle is that the product is “good enough” as it is and should be used for many years to come. That’s not a way to ensure improvements

necessary to disrupt the computing world.

Lastly, the Amazon brand will have a difficult time reaching six billion

Is Amazon a threat to Apple?

Horace Dediu: Amazon is asymmetric in many ways to Apple. Asymmetry can always be a threat because the success of one player is not necessarily to the pain of another. Thus, the “threat” is unfelt, and therefore it’s less likely that there is a response in kind. However, it’s important to couple the

asymmetry with a trajectory of improvement where the threat goes from unfelt to clear and present. That’s where I’m having a hard time putting Amazon on a path that crosses Apple’s fundamental success. I’d say it’s something to watch carefully but not yet something that requires a change in strategy.

I would add one more footnote: Apple TV is a business that matches Kindle perfectly in strategy. Apple TV is a “cheap” piece of hardware that is

What role do you see Apple playing in the

future of publishing — and what current

trends do you identify as driving factors?

Horace Dediu: I think Apple will put in a greater effort at the K-12 and higher ed levels. I think the education market resonates strongly with them, and they will develop more product strategy there. The main reason is that there are more decision makers and less concentration of channel power.

Don’t Build Social — Thoughts on Reinventing

the Wheel

By Travis Alber

For the publishing community, social reading has been the hot topic of the year. Since 2008, in fact, social features have spread like wildfire. No publishing conference is complete without a panel discussion on what’s

possible. No bundle of Ignite presentations passes muster without a nod to the possibilities created by social features. I understand why: in-content

discussion is exciting, especially as we approach the possibility of real-time interaction.

Granted, I’m biased. Running a social service myself, I think all this interest is great. The web should take advantage of new paradigms! Social discussion layers are the future! However, there is one important point that all the

myriad new projects are ignoring: unless it’s a core feature, most companies shouldn’t build social.

Services, APIs, and the Complex Web

We’ve seen this happen again and again on the web. If you’ve ever heard of

Get Satisfaction or UserVoice, you’re familiar with the evolution of customer service on the web. Ten years ago companies built their own threaded

bulletin board systems (and managed the resultant torrent of spam), so that they could “manage the user relationship.” There were some benefits — you could customize the environment completely, for example. But it took the greater portion of a week to build, and a lot of work to maintain. Today that kind of support can be up and running in an hour with third party solutions. Just ask forward thinking companies like Small Demons and NetGalley, who have embraced these services.

The same can be said of newsletters. For years newsletters were hand-coded (or text-only) and sent from corporate email accounts. Unsubscribing was difficult. Getting email accounts blacklisted (because they looked like spam) was common. Today everyone uses MailChimp, Constant Contact, Emma, or a similar service. Even if you hire an agency to design and manage a system, they’re likely white-labelling and reselling a service like this to you.

Companies no longer build a newsletter service. Now you just use an API to integrate your newsletter signup form with a third-party database. Design your newsletter using one of their templates, and let them do all the heavy lifting for email management, bounces, unsubscribes, and usage stats. There are other examples. Who stores video and builds their own player? Instead we upload it to Vimeo, Brightcove or YouTube, customize the

settings, and let the service tell you who watched it, handle storing the heavy files, push player upgrades frequently, etc. Even web hosting itself has

Publishing focus and third-party opportunity

This move to third-party social solutions should start happening with all the education, journalism, authoring platforms, writing communities and

publishing projects currently in development. Although it sounds simple to just add discussion into content, the devil is in the details. Obviously the front end — the process of adding a comment — takes some work, and the

estimation for that is fairly straightforward. But what about the paradigm that people use to connect? Are they following people in a Twitter paradigm, or is it a group-based, reciprocal model, like Facebook? Who can delete

comments? What can you manage with your administrator dashboard? Are servers ready to scale with peak activity? What kind of stats can you get on how your audience is interacting with your content? Most of these issues don’t relate to the core business.

In the end, it comes down to the project definition. Is it a bookstore or a

Startups and Publishers: It Ain’t Easy

By Hugh McGuireAny startup company trying to work with book publishers will tell you tales of woe and frustration. Big publishers and small publishers (I’ve worked with both) pose different sets of problems for startups, but the end result is a

If you sell a product publishers don’t want,

who is to “blame”?

Start-ups tend to blame “slow-moving legacy publishers” … but blame lies as much on startups misunderstanding of publisher needs as on publishers being slow. This is a classic “customer development” problem for startups. The reason things don’t work is not that “publishers are too dumb to see how they should change, and choose me to help them,” but rather that the pains

publishers are suffering, and solutions startups are offering, are probably not well matched, for a few kinds of reasons:

a) the pain startups are trying to solve is not acute enough for the publishers (yet?)

b) the cost (in time or dollars) to adopt startup solutions is too high (for now?)

c) startups are trying to solve the wrong pain (for today?)

Solutions to solve future problems

In my particular case, I’ve recognized that the PressBooks pitch ends up being something like:

Eventually you’ll need to embrace solutions like PressBooks because solutions like PressBooks will radically transform this market flooding the publishing market with more books than you ever imagined …

That is … we (and others like us) are trying to solve for publishers problems that we are helping create, and which aren’t quite here yet on a scale that is visible to the day-to-day operations of a publishing company. (Certainly these big/catastrophic problems are coming, and soon … but still, it’s a future

Where to next?

So, as a startup, you have to choose what direction to go in:

a) try to solve the pain that traditional publishers have right now, which is felt acutely enough

-or-b) (in our case) try to expand the market by helping millions of new

publishers exist … thereby helping create the problems traditional publishers will have to face in the coming years

The risk of ceding the future to other players

Still, there is a case to be made that a publisher with a vision of the future you should be out-front of the changing market. As a fellow-traveller in startup frustration, Andrew Rhomberg at Jellybooks says:

Publishing has been — technically speaking — an amazingly stable industry for a very long time. In defense of publishers: it is going through a transition from analogue to digital AND online faster than any other media industry before it. But by not partnering, publishers are ceding influence over how this industry will be shaped.

And that’s the problem for both startups and publishers … most publishing startups are trying to solve problems that will come because of innovations in the future; most publishers are worried about solving the problems of a

radically transforming industry right now.

In the end, readers will drive the change

Change is coming though, there is no doubt, and we will know it is here when big numbers of readers start to choose new solutions over existing solutions (see: ebooks). These solutions will come from a mix of startups, of old publishers and new publishers, and crucially, from the big four tech giants: Google, Apple, Amazon, Facebook (and possibly others).

It’s Time for a Publishing Incubator

By Travis AlberLast June, over beer (generally a good place to start), I had a great

conversation with entrepreneur Hugh McGuire about how startups are funded in publishing. There was a lot to discuss, a little to celebrate, a bit to

complain about, and one fact that we arrived at beyond everything else. It’s a challenge to raise money for publishing ventures.

Roadblocks

Some of the issues come straight out of the investor community:

Most investors are unfamiliar with publishing. Books seem traditional. I can’t tell you how many investors put their personal feelings into the equation and say things like, “Well, my spouse is in a book club, but I don’t read much so I’m probably not a good fit.” Ouch. Although personal experience figures in somewhat, their total unfamiliarity with the market stops them cold before we’ve even started.

Concerns about returns on investment. It’s true, we haven’t seen the huge acquisitions like Instagram. Or Yammer. Yet. Publishing is worth billions - it has what everyone wants: content. So maybe the book industry doesn’t seem like a high growth market. One thing is certain, though, as the

industry goes digital, those publishing billions are going to be spent on something. Clear exits will materialize.

There’s always the What-If-Google-Does-It argument. To be fair, every startup gets the Google, Amazon, Apple question, which goes something like “What will you do if (all together now), Amazon, Apple, or Google does it?” A few weeks ago I heard Henrik Werdelin of Prehype give a presentation at a TOC event about innovation and he chuckled about this specific question. He pointed out that at this point Google can pretty much build anything anyone can invent. That shouldn’t be your yardstick. The better question is, are the founders smart enough to offer good strategy, a unique experience, or a new market? If so, Google is much more likely to buy the company once the idea proves out, rather than build every single idea in the world. In short, that question is not a question.

True, there are some people who get investment while working on publishing startups. The list above can be overcome if you’ve worked with those

investors before. Or if you’re an Ivy-League ex-Googler that has had a

successful exit, you have qualifications that will work in your favor. But that is a frightfully small portion of the people with boots on the ground,

developing cool ideas. What about the technically savvy people who don’t meet those criteria (most of the people I know innovating in publishing

today)? If they’re starting up in Amercia, those people go out and crash head-first into the arguments listed above, then spend a few years toiling in

People have been thinking about this for

awhile

Last October Brian O’Leary gave a stirring talk, The Opportunity in Abundance, at the Internet Archive’s Books in Browsers conference (transcribed here). He put forth a bold vision of collaboration among

publishers, each contributing to support innovation and enjoy in its technical fruits. He talked about goals — that survival for publishing is not a “goal” in itself, for example — and that innovation is one of the important pillars of publishing health. He used an example from the gas industry to illustrate how it pooled resources to innovate. He said:

I called the prospect of people not engaging with our content the publishing manifestation of a super-threat. I’d argue (pretty strongly) that it represents a super-threat not just to publishing, but to the way we function as a country, an economy and as a part of a world order. We have a responsibility to address this threat, not just so that we can make money, but because we’re the ones with the ability to solve it.

Other industries facing an uncertain future have banded together to form and fund superstructures. The Gas Research Institute, for example, was authorized in 1976, at a time when the natural gas industry was highly fragmented among producers, wholesalers and distributors. The latter often held a local monopoly.

By 1981, GRI was spending $68.5 million on research and a total of $80.5 million on oversight and R&D. This represented about 0.2% of the wellhead price of gas that year, valued at the time at a bit more than $38 billion.

GRI undertook research and development in four areas…Funding, drawn from a surcharge on sales as well as some government grants, accelerated to something north of $100 million in the mid-1980s.

If you look across all of publishing in the United States, it’s about a $40 billion business. Imagine what we could do if we could create and sustain an organization with $80 million a year in

funding. It’s also likely that an industry-wide commitment to addressing engagement would garner the external funding that most parties have been understandably reluctant to spend on narrower causes.

A good point. A great plan. If CourseSmart and Bookish show us that publishers can partner, then why not partner in innovation? Brian gives a number of concrete suggestions for areas to focus on. I’ve been mulling this over ever since he gave this presentation. Despite his guidelines and

The publishing incubator

A similar solution already exists in the tech world: the incubator. If you’re not familiar with it, technology incubators accept applications from startups in small batches. If accepted, the startup gets between $20,000 - $100,000 (in exchange for around 5% equity), along with three months of office space, mentors, a chance to demo for investors, and a lot of help. Investors get early access to cutting-edge technology. Corporations are encouraged to come in and meet the startups at any point along the way.

Many incubators are industry-specific. For example, there are four healthcare incubators in NYC alone, churning out fresh startups and new technology multiple times a year. Imagine the amount of healthcare innovation going on right now. Education does this too. Incubator ImagineK12 is one of many education-focused incubators from across the country — with a group of startups that has raised $10M post-graduation. And Turner Broadcasting just launched an incubator in NYC called Media Camp. Since the products

integrate with broadcast media, there is a major focus on mentorship from executives in the field, and a lot of discussion about how to work with big media conglomerates. Sounds a lot like what we need in publishing. Even publishing expert Craig Mod recently wrote about how he is struggling with how to distribute his TechFellow money to startups.

Granted, there is some remarkable internal R&D: NYTimes Labs and The Washington Post Labs are doing good things. Those are commendable efforts. But those teams are usually small, and since they’re internal they don’t have the massive variation we see in incubators. One company isn’t going to move the needle for an entire industry in that way.

We need an incubator for publishing technology. We need a group of

This should exist now. I’ve been working on publishing startups for five years and I have yet to see it. Moreover, with so many publishers on the East Coast, New York City is the place to do it. New York has a healthy startup industry, access to publishers and publishing conferences, mentors and experts. My question is, who’s going to do something about it? Who’s with

The Slow Pace of eBook Innovation

By Joe WikertI love this comment from Dave Bricker regarding an earlier post, EPUB 3 facts and forecasts:

Ebook vendors enjoy a closed loop ecosystem. They have millions of reader/customers who are satisfied with EPUB 2 display capabilities and devices. Amazon readers, for example, are largely content with the offerings in the proprietary Kindle store; they’re not lining up with torches and pitchforks to push for improvements. While publishers wait for eReader device manufacturers to add new features and EPUB 3 support, eBooksellers are just as happy to wait.

The best way to promote EPUB 3 right now is to bypass it in favor of delivering ultra-innovative books through the web and app-based distribution. When we can give eReader device makers a compelling reason to bring eReaders into parity with apps and webkit browsers, they’ll put their mouths where our money is. Until eBookstores know they’re losing sales to alternative/open channels, they’re going to sit pretty, stall, and make money doing what they’re doing.

Who’s pushing for innovation in the ebook space? Publishers? No, they’re fairly content with quick-and-dirty p-to-e conversions and they’re risk averse when it comes to making big investments in richer content formats.

Retailers? Nope. If retailers were motivated we’d see much broader adoption of EPUB 3 in the various readers and apps out there.

This reminds me of the Android challenge. It’s widely known that new versions of the Android OS don’t get adopted as rapidly as new versions of Apple’s iOS do. That’s because the carriers (e.g., AT&T) and handset makers (e.g., Samsung) have no incentive to update all the existing devices. They’d prefer to force you into a new phone rather than give you a quick OS update with all the new features.

This is one area that Apple really understands and gets right. When they come out with a new version of iOS they have it pushed out to as many customers as possible (assuming their devices can support it). Apple knows there’s so much sex appeal for each new device they don’t have to starve existing device owners from the new OS features.

Putting a Value on Classic Content

By Robert CottrellThink of a newspaper or magazine as a mountain of data to which a thin new layer of topsoil gets added each day or each week. Everybody sees the new soil. But what’s underneath gets covered up and forgotten. Even the people who own the mountain don’t know much about the lower layers.

That wouldn’t matter if old content was bad content. But it’s not. Journalism, at least good journalism, dates much less than we are prone to think.

You never hear anybody say, “I’m not going to listen to that record because it was released last year”, or, “I’m not going to watch that film because it came out last month”. Why are we so much less interested in journalism that’s a month or a year old?

The answer is this: We’ve been on the receiving end of decades of

salesmanship from the newspaper industry, telling us that today’s newspaper is essential, but yesterday’s newspaper is worthless.

Look who’s talking. It’s been 50 years since newspapers had the main job of telling people what’s new that day. For decades they’ve been filling their pages with more and more timeless writing. The process is all but complete. Go back into the features pages of your favourite newspaper from a year ago, and you’ll find scarcely a piece that couldn’t appear just as easily today, with a few very minor changes.

All this boils down to a simple proposition: old content is undervalued in the market, relative to new content. There are tens if not hundreds of thousands of articles in writers’ and publishers’ archives which are as good to read today as they were on the day they were published. Yet they are effectively valued by their owners at zero, written off, never to be seen again.

I say all this with feeling because for the past five years I have been curating a recommendations site, The Browser, picking out six to eight of the best pieces published online each day. The thought of all these thousands of pieces, every one a delight, lying dormant in archives, strikes me as deeply unfair to both writers and readers.

do almost none of them (the New Yorker is an honourable exception) make any serious attempt to organise, prioritise and monetise their archives? They, after all, are the owners of the mountains, and whatever treasures may lie buried within.

The answer is that they are too fixated on adding the daily or weekly layer of new topsoil. Some of them, I know from experience, see any serious effort to monetise their archive content as a form of competition with their new

content. At most, they may have some “related content” algorithms, but those algorithms are only going to be as good as the database tagging, which is to say, not good at all.

Reading Experience and Mobile Design

By Travis AlberIt’s all about user experience. Once you get past whether a book is available on a particular reading platform, the experience is the distinguishing factor. How do you jump back to the table of contents? How do you navigate to the next chapter? How do you leave notes? How does it feel? Is it slick? Clunky? Satisfying? Difficult? Worth the money?

Mobile design?

Mobile design patterns and best practices overlap with the way we design (or should design) reading experiences. It’s a simple concept that may seem unremarkable — that generic concepts in mobile design and user experience apply when putting together a reading system — but it’s actually at the heart of building something in publishing today.

If this sounds technical, it isn’t. If you’ve used a smartphone to read email, a tablet to read magazines, or an e-reader to consume content, you’re

Five convergence points for mobile design &

reading system design

1. Simplicity is really, really important

For people using a mobile device, connections are slow. Images need to load quickly. There isn’t space to explain (or use) 20 different features. People close apps before bothering with a FAQ. People are impatient. Knowing this, mobile UX designers are specific about what goals they design for, and they stick to those. Most mobile apps do just a few things, and they strive to do them well. That keeps apps very straightforward and simple.

Obviously simplicity has always been a sign of an optimal reading experience. Open and read, right? In fact, it’s best if most of the chrome around a book disappears, so readers can focus on the content. It’s natural that the most successful reading systems need to follow this principle of mobile design.

2. Everything takes place in the context of our lives

The first thing UX designers learn when working on a mobile project: people use phones while doing other things. They use them one-handed. They often use them when they are not at home. Design for sub-optimal conditions, because you never know if you have someone’s complete attention. Reading also takes place within the contextual fabric of how we live our lives. People read books on the subway. At the doctor’s office. In coffee shops. Loud noises, phone calls, check-ins, and conversations all disrupt the experience, even with paper books. As long as we have an easy way to mark our place, a simple way to carry it with us, and a graceful way for features to fail until we can get back to optimal conditions (for example, in the way a reading service might need to reconnect to upload notes), reading systems will act like people expect them to: consistently.

3. No one will wait to read

The same is true of mobile. There are a number of design patterns created to notify the user that content is loading. Different loading bars and contextual messages are designed to manage people’s expectations in a world of high-speed internet, where most clicks bring content to them instantly. This is called latency, and it will drive users away. In both reading systems and mobile apps, latency needs to be under control.

4. Patterns matter

Mobile design patterns create a uniform experience across applications. For example, if you’re filling out a form in a mobile app, there are some best practices the designer has (hopefully) followed, like saving your data as you enter it (people typing with their thumbs don’t have a lot of patience if they have to do it twice), or preserving that data if an error message loads (for the same reason). Granted, these are good guidelines on the web too, but they are really of paramount importance in mobile. These best practices are used inside recommended patterns, so layouts must have optimal places for error messages, or easy ways to update content. You see those patterns repeated in the way lists and forms work across all your mobile apps. (I use patterns and

best practices loosely here, the exact definition of each is eternally debated among UX professionals.)

How does this relate to reading systems? On one level, the same applies to users adding notes or reading socially — respect the data because most

people won’t enter it twice. But it also has a lot to do with design patterns for reading. The way a table of contents is treated, the way people move through books, the expectation that there will be a way to bookmark a section — these are all patterns.

Last month, at Books in Browsers, Craig Mod gave a presentation on

Subcompact Publishing. In it he talks about how, if you need a screen of instructions on how to use your reading app, it’s probably too complex. To avoid this, UX designers need to pay attention to user expectations and

habits. Everything from page-turn options, to title visibility to a linkable table of contents, these rules are being created now, and they need to be followed consistently.

5. APIs will be the source of interactivity and real-time action

applications are richer; these capabilities live on top of an app’s core system. Expect to see the same thing in reading systems. Although many reading systems are a bit too immature to allow full EPUB 3 capabilities, they will evolve to allow JavaScript and the ability to bring in real-time data. iBooks does this with limited ability now. Enhancements that make reading better without being a direct part of the book are going to very popular. And readers will expect it in the way they expect it from mobile apps.

Serial Fiction: Everything Old Is New Again

By Alice Armitage2012 may be remembered as the year that digital publishing brought serial fiction back to the reading public. Readers in the 19th and early 20th

centuries often read fictional stories in installments in newspapers and magazines: books were simply too expensive for many people. But as affordable paperbacks flooded the market in the mid-1900s, serials lost popularity. Now, however, the ease of delivering installments to digital devices, combined with the limited time people have to devote to reading, is leading to a resurgence of interest in serial fiction.

Serial fiction has been available on the web since the 1990s. But suddenly in the last six months, there has been an explosion of interest in fiction delivered in installments: Amazon announced its Kindle Serials program, publishing startups introduced their own serial fiction series, (e.g., Byliner, Wattpad, and

Why should you be interested in serial fiction?

Whether you are looking at this development as a publisher, reader, or author, there are plenty of reasons.

For a publisher, serial fiction provides ongoing engagement with your readers. Each new installment is delivered to them automatically on their device of choice, bringing your product back into the forefront of their minds. The episodic nature of serial fiction may also increase the buzz around the author and the story, as there is often a lively online discussion among readers about what may happen in future installments. This enhances

discoverability by creating more opportunities for new readers to hear about the product.

Perhaps most interesting for publishers is the flexibility in payment options for serial fiction. For example, Kindle Serials charges one low price for the purchase of the series up front, with each subsequent installment delivered for free. If the series is well-subscribed, when it is complete, it is offered for sale as a book, either as a paperback or as a Kindle edition. The price for this often exceeds the price for the series if purchased when it began. Other

Frequency, engagement, and experimentation

The shorter the installment, the more often it is likely to be delivered. For example, Silent History delivers a new installment each weekday for four weeks and then takes a break for a week to let everyone catch up before issuing new installments. Where a reader plans to read each installment may be a factor in what they purchase. For example, someone looking for

something to entertain them during their 30 minute commute will most likely want longer installments than someone looking for a diversion while they wait in line for 10 minutes at the bank. But for someone about to begin a three-hour plane flight, a few installments of novella length may be the most appealing. Readers may also like serial fiction for the option it provides for interaction with the author through online discussions of upcoming

installments, which may influence the direction of the story. (Authors have reported they have changed the ending or the level of involvement of

secondary characters based on reader feedback.) And lastly, the need for cliffhangers at the end of each installment, as well as other techniques for bringing readers back to the story after a waiting period, means that serial fiction is often more intricately plotted and engaging than a stand alone book might be.

It still comes down to great writing

Overall, after reading many different kinds and examples of the serial fiction that has recently burst onto the scene, I have to say I like the flexibility of matching my current reading needs (the length of time I have, my attention span at the moment, the situation I’m reading in — is it a quiet doctor’s office or the DMV?) with all the different sorts of serials available at an affordable price. And I am amused by the new ways of telling stories

utilizing the bells and whistles of my mobile devices. But I have discovered that the measuring stick for serials is the same as the one I use for all books: How good is the writing? Over time, neither the novelty of periodic delivery of installments nor the new storytelling techniques available through my device kept me interested in the story unless the plot was intriguing, the

characters were fully developed, and the writing was engaging. Bottom line: I like the flexibility of serial fiction, but only good writing will keep me

Getting the Content Out There Isn’t Enough

Anymore

By Jenn Webb

Content is still king, but now it has to share its crown. Justo Hidalgo (@justohidalgo), co-founder of 24symbols, believes added value and

In what contexts does content aggregation

create the most value?

Justo Hidalgo: Companies that take content and contribute added value for readers are generally better positioned to succeed. Specifically, I believe content aggregation is useful in the following contexts:

Hubs — Why did The Huffington Post gain so much success? Why is Spotify increasing its number of users constantly? And why is Netflix in trouble? There are of course many reasons, but one is particularly clear: Users want hubs where they can find most, if not all, of the content they want. Content aggregation enables just that. While creating silos of

information can be valuable in specific niche markets, it does not work in mass markets unless your brand recognition is immensely high.

Value addition — Social recommendation is a typical yet good example of value addition to content, as is adding information about a title’s author and surrounding context. This meta-information can be manually or

automatically added. I believe in the power of machine learning and data mining technologies applied to this area, along with human expertise.

How about paywalls — is anyone doing this

properly? What is the best way to make this

model work?

Justo Hidalgo: Paywall models only work if what you offer is extremely exclusive. Maybe the New York Times or the Financial Times can succeed at offering paywall content, but in a digital world absolutely nothing can be prevented from being copied and propagated. So the key is not the content itself, but the value-added service offered on top of it. Only a mixture of high-quality content and a great service will be compelling enough to make users pay.

In general, the content — and the service that contains it — needs to be testable, and models like freemium, whether “free” is forever or for a limited time, are critical in the digital content world. Spotify is creating a massive user base with this model, even now that its free offering is not as compelling as before. The New York Times is also using a freemium approach, letting its users read a few articles per month for free before the paywall kicks in.

24Symbols is based on a subscription model.

Since your launch, have you had to change

the model to make it work?

Justo Hidalgo: Pivoting is inherent to any startup. We made some changes to our product strategy, like focusing on the HTML5 version before the native apps for iOS and Android.

In terms of the model, the basics are the same. We believe a cloud-based social reader with a freemium subscription model is key for the future of publishing. And we recently branched out to license our technology to

companies and institutions that want to offer a cloud reader to their customers or employees. This was in our minds from the start, but we wanted to focus on the consumer offering first and create a top-class platform.

Amazon, eBooks, and Advertising

By Joe WikertIt all started harmlessly enough with Amazon’s Kindle with Special Offers. That’s the cheaper Kindle that displays ads when the device is in sleep mode or at the bottom of the screen when paging through the owner’s catalog of books. It is very unobtrusive and, since it lowered the price of the device, has made that Kindle an extremely popular device.

Now there are rumors that Amazon is selling ad space on the Kindle Fire’s welcome screen. That sounds pretty reasonable, too, as it’s a simple way for Amazon to drive a bit of additional income that’s pure profit for them.

Given that Amazon’s goal is to offer customers the lowest prices on everything, what’s the next logical step? How about even lower prices on ebooks where Amazon starts making money on in-book ads? Think Google AdWords, built right into the book. Of course, Amazon won’t want to use Google’s platform. They’ll use their own so they keep 100% of the revenue. The changes the DOJ is requiring for the agency model means a retailer can’t sell ebooks at a loss, but they can still sell them for no profit, or break even. In other words, the 30% the retailer would keep on an agency ebook sale can be passed along to the customer as a 30% discount on the list price, but that’s as deep a discount as that retailer can offer.

The rules are different with the wholesale model. Amazon already loses money on sales of many wholesale-model ebooks. Let’s talk about a

hypothetical wholesale model title with a digital list price of $25. Amazon is required to pay the publisher roughly half that price, or about $12.50 for every copy sold, but that ebook might be one of the many that are listed at $9.99 for the Kindle. So every time Amazon sells a copy, they lose $2.51 ($12.50 minus $9.99). Amazon has deep enough pockets to continue doing this, though, so they’re quite comfortable losing money and building market share.

building market share, why doesn’t it also make sense to sell them at $4.99, $0.99 or even free for some period of time? It probably depends on how much pain Amazon wants to inflict on other retailers and how much attention they’re willing to call to themselves for predatory pricing.

Make no mistake about the fact that Amazon would love to see ebook pricing approach zero. That’s right. Zero. That might seem outlandish, but isn’t that exactly what they’re doing with their Kindle Owner’s Lending Library

program? Now you can read ebooks for free as part of your Prime

membership. The cost of Prime didn’t go up, so they’ve essentially made the consumer price of those ebooks zero.

Why wouldn’t they take the same approach with in-book advertising? At some point in the not-too-distant future, I believe we’ll see ebooks on Amazon at fire-sale prices. I’m not just talking about self-published titles or books nobody wants. I’ll bet this happens with some bestsellers and midlist titles. Amazon will make a big deal out of it and note how these cheaper prices are only available through Amazon’s in-book advertising program. Maybe they’ll still offer the ad-free editions at the higher prices, but you can bet they’ll make the ad-subsidized editions irresistible.

Remember that they can only do this for books in the wholesale model. But quite a few publishers use the wholesale model, so the list opportunities are enormous. And as Amazon builds momentum with this, they’ll also build a very strong advertising platform. One that could conceivably compete with Google AdWords outside of ebooks, too.

Publishers and authors won’t suffer as long as Amazon still has to pay the full wholesale discount price. Other ebook retailers will, though. Imagine B&N trying to compete if a large portion of Amazon’s ebook list drops from $9.99 to $4.99 or less. Even with Microsoft’s cash injection, B&N simply doesn’t have deep enough pockets to compete on losses like this, at least not for very long.

By the time all that happens, Amazon will probably have more than 90% of the ebook market and a nice chunk of their ebook list that no longer has to be sold at a loss. And oh, let’s not forget about the wonderful in-book

advertising platform they’ll have built buy then. That’s an advertising revenue stream that Amazon would not have to share with publishers or authors. That might be the most important point of all.

What do you think? Why wouldn’t Amazon follow this strategy, especially since it helps eliminate competitors, leads to market dominance and fixes the loss-leader problem they currently have with many ebook sales?

New Life for Used eBooks

By Joe WikertI’ve got quite a few ebooks in two different accounts that I’ve read and will never read again. I’ll bet you do, too. In the print world, we’d pass those along to friends, resell them or donate them to the local library. Good luck doing any of those things with an ebook.

Once you buy an ebook, you’re pretty much stuck with it. That’s yet another reason why consumers want low ebook prices. Ebooks are lacking some of the basic features of a print book, so of course they should be lower-priced. I realize that’s not the only reason consumers want low ebook prices, but it’s definitely a contributing factor. I’d be willing to pay more for an ebook if I knew I could pass it along to someone else when I’m finished with it.

The opportunity in the used ebook market isn’t about higher prices, though. It’s about expanding the ebook ecosystem.

The used print book market helps with discovery and affordability. The publisher and author already got their share on the initial sale of that book. Although they may feel they’re losing the next sale, I’d argue that the content is reaching an audience that probably wouldn’t have paid for the original work anyway, even if the used book market didn’t exist.

Rather than looking at the used book world as an annoyance, it’s time for publishers to think about the opportunities it could present for ebooks. I’ve written and spoken before about how used ebooks could have more functionality than the original edition. You could take this in the other

direction as well and have the original ebook with more rich content than the version the customer is able to either resell or pass along to a friend; if the used ebook recipient wants to add the rich content back in they could come back to the publisher and buy it.

As long as we look at the used market through the lens of print products, we’ll never realize all the options it has to offer in the econtent world. That’s why we should be willing to experiment. In fact, I’m certain one or more creative individuals will come up with new ways to think about (and distribute) used ebooks that we’ve never even considered.

“lets you store, stream, buy and sell pre-owned digital music.” As the article points out, ebooks are next on ReDigi’s priority list. Capitol Records is suing to shut down ReDigi; I suspect the publishing industry will react the same way. Regardless of whether ReDigi is operating within copyright law, I think there’s quite a bit we can learn from their efforts. That’s why I plan to reach out to them this week to see if we can include them in an upcoming TOC

event.

By the way, even if ReDigi disappears, you can bet this topic won’t. Amazon makes loads of money in the used book market and Jeff Bezos is a smart man. If there’s an opportunity in the used ebook space, you can bet he’ll be working on it to further reinforce Amazon’s dominant position.

In-Book Purchases

By Joe WikertWe’re all familiar with the in-app purchase model. It’s a way to convert a free app into a revenue stream. In the gaming world it’s an opportunity to sell more levels even if the base product wasn’t free. Each of the popular ereader apps allow you to purchase books within them, of course, but why does it end there? What if you could make additional purchases within that ebook?

Here’s an example: I’m almost finished reading Walter Isaacson’s terrific biography of Steve Jobs. I paid $14.99 for the Nook version and as I’ve read it I’ve been tempted to go out to YouTube and relive some of the interviews and product launches Jobs did over the years. I didn’t do that though, mostly because it would have required me to close the ebook and search for the relevant video.

I would have paid an extra $5 for an enhanced version of the book with all the YouTube videos embedded (or linked to). Sell me the base edition for $15 and let me decide to upgrade to the richer version for an additional price. Even though everyone won’t necessarily upgrade why not make the option available to those who might?

My example is pretty simplistic but the lesson here is to think about how a single product can be re-deployed as multiple products. Think basic,

enhanced and premium editions, each at different price points and upgradable to the next level. The most successful approach here is likely one where the basic edition is as inexpensive as possible and readers are given a compelling reason to upgrade to the enhanced and premium editions.

What do you think? Is this a viable model and can it be implemented in today’s walled gardens or will it have to wait till more ebooks are being sold direct to consumers by the publisher?

Why a Used eBook Ecosystem Makes Sense

By Joe WikertIn an earlier post I mentioned my plans to speak with ReDigi, the company making waves by helping consumers resell their digital music. One day consumers will also be able to resell their ebooks via ReDigi and that has some publishers concerned. What’s a “used ebook” anyway and should consumers be allowed to resell them? I felt the answer to the last part of that question was “yes” before I spoke with ReDigi founder John Ossenmacher but our conversation convinced me even more that reselling ebooks will be a good thing for everyone.

I should first mention that at O’Reilly we already allow you to resell the ebooks you buy directly from us. Here’s a link to the terms on our website. If you’re not a fan of consumers reselling their ebooks I ask you to consider two key points John made in our conversation: authentication and revenue. One of the first steps you take after joining ReDigi is to let the service scan your music collection so they can determine what’s legit and what’s not. That’s right, ReDigi is able to analyze your music collection to determine which songs you bought from services like iTunes vs. the songs you illegally downloaded from a torrent site. RedDigi only lets you resell songs they’ve identified as legitimate purchases. John tells me their ebook service will have the same forensic capabilities. That means pirated books cannot be resold through ReDigi. Better yet, the ReDigi service also puts a little “make me legal” reminder next to every illegal file it finds in a customer’s collection. Click on that reminder and you’ll be able to pay for each of those pirated files to make them legit. How cool is that?

Still not convinced it’s a viable service? What if I told you the IP owner also gets a cut of the resale transaction? It’s true. When ReDigi launches their ebook reselling platform publishers (and therefore authors) will get part of the resulting revenue stream. Good luck making that happen at a used print book shop!

Seeing what ReDigi is up to makes me even more excited about the future of reselling digital content. I also wonder if consumers will tolerate higher

In the Case of Interactivity, We’re Still at the

Phase of Irrational Enthusiasm

By Jenn Webb

When it comes to including interactive features in books, “just because you can doesn’t mean you should” may be your best rule of thumb. In the

Where do you draw the line between

meaningful and gimmicky interactivity?

Theodore Gray: It’s all about communication. If an interactive feature helps communicate an idea, helps the reader understand a complicated concept, or in some way makes the material easier to navigate, search, organize, or visualize, then it’s probably a good feature. If it’s just cool but tends to distract from the material, then maybe it’s a good idea for a game but not as an interactive element in a book.

Very much the same principle applies to film editing, where one must always be willing to throw out one’s favorite scene because, however cool it is, it does not contribute to the story. In fact, the more cool and amazing a scene or feature is, the more on guard you have to be that perhaps the only reason you like it is because it’s cool, not because it has earned a proper place in the film or book you’re working on.

It’s hard to be more specific because every situation is so different, but in general, I believe in the principles of minimalism expounded by the likes of

Are there times when interactivity is

detrimental and should be avoided?

Theodore Gray: There are certainly some kinds of activity on the screen that are purely bad — for example, animated images that keep playing while you’re trying to read. On the web, people learned years ago how incredibly annoying this is, but the allure to designers is so strong that it seems we need to learn the lesson all over again. A quick movement as an image comes on screen is fine, but if there is body text meant to be read on a page, then the images had better stop moving within a second or less. I think continuous animation is fine on a menu or title page where the focus should actually be on the moving images, but not on a body text page where it is a pure

distraction.

How have mobile platforms changed the

publishing landscape?

Theodore Gray: The large-scale switch to conventional, static ebooks for trade books and scholarly monographs is clearly under full steam, and while print books are here for a very long time, the center of gravity is clearly

shifting to ebooks. But this hasn’t really fundamentally changed the dynamics of publishing. Yes, there are power struggles between publishers and retailers over price points, margins, etc., but that’s nothing new. Publishers have been fighting with retailers for a generation, and I think the introduction of static ebooks is part of a continuous evolution in these power relationships, not, at this point, a fundamentally new thing.

What kinds of tools do authors need to create

interactive content, and what new skills might

they need to develop?

Theodore Gray: Good interactivity is hard. Fundamentally, it’s the same skill set needed for any kind of software development, which means hard-core programming talent, interactive/game design skill, and visual design skill. There are some tools that can make interactivity much easier within limited domains, but most of these result in shallow — which is to say bad — interactivity.

For highly technical kinds of interactivity, Wolfram|Alpha and Wolfram’s

Computational Document Format are attractive tools, in that they allow very deep computation and data-based interactivity with minimal software

![Figure 13-5. Three books produced by the BookJS in-browser typesetting library [photo by KristinTretheway]](https://thumb-ap.123doks.com/thumbv2/123dok/3940033.1883453/235.612.84.530.73.527/figure-books-produced-bookjs-browser-typesetting-library-kristintretheway.webp)